Abstract

Whether Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus can be recovered after passage through the human gut was tested by feeding 20 healthy volunteers commercial yogurt. Yogurt bacteria were found in human feces, suggesting that they can survive transit in the gastrointestinal tract.

Yogurt, defined as the product of milk fermentation by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus, has a long history of beneficial impact on the well-being of humans. In a few articles workers have focused on the scientifically documented impact of yogurt cultures alone on gut metabolism (1, 23). Yogurt bacteria have been shown to improve lactose digestion in lactose-intolerant individuals (16, 17, 20, 21, 27), to affect the intestinal transit time (11), and to stimulate the gut immune system (2, 14, 31), although some authors failed to confirm these conclusions (5, 6, 35). The immunological and genetic basis of the immunostimulatory properties of yogurt starters has also been investigated (8, 15).

Nevertheless, the scientific background of these studies and the application of the term “probiotic” to the starter bacteria L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus are still strongly debated (13, 33). As indicated by Guarner et al. (13), recent scientific developments have challenged the validity and usefulness of the in vitro selection criteria traditionally proposed for probiotics.

Traditional yogurt starters have nonhuman origins, and they (especially streptococci) are known to suffer from exposure to gastric acidic conditions (7) and to have a moderate ability to adhere to intestinal epithelial cells (12).

Survival during passage through the gastrointestinal tract is generally considered a key feature for probiotics to preserve their expected health-promoting effects (3).

There have been conflicting studies concerning the recovery of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus from fecal samples after daily yogurt ingestion. Some authors reported that L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus were not recovered from feces of young (9) and elderly (26) subjects. On the other hand, Brigidi et al. (4) reported that for 6 days after the end of treatment, they recovered S. thermophilus from fecal samples from 10 healthy subjects who had ingested a pharmaceutical preparation orally for 3 days. The persistence of a yogurt culture in the human gut was also recently confirmed by Mater et al. (22), who studied 13 healthy volunteers fed yogurt containing rifampin- and streptomycin-resistant strains of S. thermophilus and L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus.

The aim of this study was to investigate the recovery of viable L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus from fecal samples from 20 healthy volunteers fed commercial yogurt for 1 week.

Our study included 10 male and 10 female healthy subjects whose mean age was 32.3 years. These subjects ate 125 g of commercial yogurt (Bianco Naturale; Danone) twice a day for 1 week. The volunteers, who were divided into two groups of 10 subjects, were investigated once to determine the persistence of yogurt cultures in fecal samples.

Two subsequent trials (trials 1 and 2) were perfromed with 10 subjects each. The volunteers were required to abstain from consumption of yogurt and fresh dairy products for 2 weeks before the beginning of the trials. The daily intake of bacteria from yogurt, containing 2.4 × 107 CFU/g of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and 2.0 × 108 CFU/g of S. thermophilus, was about 6 × 109 CFU of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and 5 × 1010 CFU of S. thermophilus.

Fecal samples, which were obtained at the beginning of each trial (zero time) and after 2 and 7 days, were stored for a maximum of 12 h at 4 to 8°C. A 1-g sample of fecal material was decimally diluted in sterile saline and plated onto skim milk medium (RSMA) (Difco, BD, Sparks, Md.) in trial 1. In trial 2, RSMA was supplemented with 0.05% ruthenium red dye (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) to obtain modified RSMA (m-RSMA). In both cases the plates were incubated at 44°C for 48 h.

In this study great emphasis was placed on selection of a medium suitable for reliable and reproducible detection of lactobacilli and streptococci in feces. The ability of RSMA to support the growth of clearly distinguishable colonies was determined, and the performance of this medium was refined by addition of ruthenium red dye (24) (m-RSMA), which allowed us to clearly distinguish the white halos of small Enterococcus colonies from the pink halos of Lactobacillus and Streptococcus colonies. After prolonged incubation at 44°C, colonies on m-RSMA plates changed from pink to fuchsia for streptococci and from old rose to yellow for lactobacilli, which allowed us to prescreen the fecal microflora of treated volunteers and to reduce the number of isolates that were identified by molecular tools.

Colonies having Lactobacillus- and Streptococcus-like morphologies on days 2 and 7 were replica plated, using 10% of the colonies recovered from the first readable plate, onto MRS medium (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) and LM17 medium (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom), respectively, incubated at 44°C for 48 h, and directly lysed with MicroLYSIS (Microzone Ltd., Haywards Heath, West Sussex, United Kingdom). Lysed suspensions were used as templates in species- and strain-specific PCRs.

L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus strains that were used as controls in amplification experiments were isolated from commercial yogurt by plating on RSMA, and their taxonomic identities were confirmed by using molecular tools.

A three-step identification protocol was used for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus-like colonies grown on selective medium, using primers SS1 and DB1 (10) for L. delbrueckii species and primers 34/2 and 37/1 (18) for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and the cycling conditions described previously. Colonies from days 2 and 7 that gave the expected amplicon size with the PCR primers of Lick et al. (18) were then analyzed by the repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (Rep-PCR) technique using primer GTG5, as described by Versalovic et al. (32), to confirm the identities of fecal isolates from subjects who had consumed yogurt and orally administered L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus isolates.

A two-step identification protocol was used for S. thermophilus-like colonies, which involved primers upstream and downstream of the lacZ gene (19). Isolates that were confirmed to be S. thermophilus isolates were then analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) because of the lack of reliable PCR primers that could distinguish between the closely related species S. thermophilus and Streptococcus salivarius present in human oral cavity (28, 34). Profiles of SmaI-digested chromosomes, obtained as described by O'Sullivan and Fitzgerald (25), were compared in order to determine strain identities.

Molecular biology tools were used for strain-specific identification of orally administered yogurt strains isolated from fecal samples previously plated onto RSMA (trial 1) and m-RSMA (trial 2). The total counts obtained on these media resulted in a maximum concentration of 107 viable cells per g (fresh weight) of feces in both trials before consumption of yogurt (zero time). Moreover, a significant increase in the counts, especially in trial 2, was observed after 1 week of yogurt consumption (day 7) for 4 of 10 volunteers whose initial counts in this medium were very low (around 103 CFU per g [fresh weight] of stool).

The absence of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus strains from fecal samples obtained at zero time was investigated and confirmed (data not shown).

Recovery of viable yogurt strains in trial 1.

After 1 week of treatment, 41 fecal isolates were subjected to PCR analysis with L. delbrueckii species-specific primers, which led to identification of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in 35 cases involving 6 of 10 volunteers, as shown in Table 1. The numbers of viable L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus CFU in fecal samples are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Recovery of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus from fecal samples after yogurt ingestion

| No. of detections per subjecta | No. of subjects whose feces contained viable yogurt strains

|

|

|---|---|---|

| L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus | S. thermophilus | |

| Trial 1 | ||

| Two | 1 | 0 |

| One | 5 | 0 |

| None | 4 | 10 |

| Trial 2 | ||

| Two | 6 | 0 |

| One | 1 | 1 |

| None | 3 | 9 |

| Total | 20 | 20 |

Two indicates detection of the microorganism on days 2 and 7, while one indicates that the strain was detected only on day 7.

TABLE 2.

Concentrations of viable L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in feces of subjects who consumed yogurta

| Trial | Subject | Concn (log10 CFU/g [wet wt] feces)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | Day 7 | ||

| 1 | 1 | NDc | 3.7 |

| 2 | 4.0 | 3.9 | |

| 3 | ND | 3.6 | |

| 4 | ND | 3.3 | |

| 5 | ND | 3.0 | |

| 6 | ND | 4.0 | |

| 2 | 7 | 5.5 | 5.1 |

| 8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | |

| 9 | 5.6 | 3.8 | |

| 10 | 5.2 | 4.7 | |

| 11 | ND | 5.7 | |

| 12b | 4.0 | 5.0 | |

| 13 | 4.5 | 5.0 | |

Subjects whose feces did not contain viable yogurt strains were not included (see Table 1).

The feces of this subject also contained 5.6 log10 CFU of S. thermophilus per g (wet weight) on day 7.

ND, viable L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus not detected.

No Streptococcus-like colonies were retrieved from plates on day 2 or on day 7.

Recovery of viable yogurt strains in trial 2.

Fecal colonies from day 2 samples (110 Streptococcus-like colonies and 110 Lactobacillus-like colonies) and from day 7 samples (23 Streptococcus-like colonies and 19 Lactobacillus-like colonies) were replica plated onto MRS and LM17. Higher numbers of colonies were investigated for day 2 in order to confirm the reliability of m-RSMA for distinguishing between enterococci, lactobacilli, and streptococci.

The presence of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in feces was confirmed for 6 of 10 human subjects on day 2, and the number increased by day 7, when orally administered Lactobacillus was present in 7 volunteers (Table 1). The fecal counts for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, as confirmed by using strain-specific molecular tools, appeared to increase in trial 1 (Table 2), which confirmed the improved performance of m-RSMA compared to the performance of RSMA.

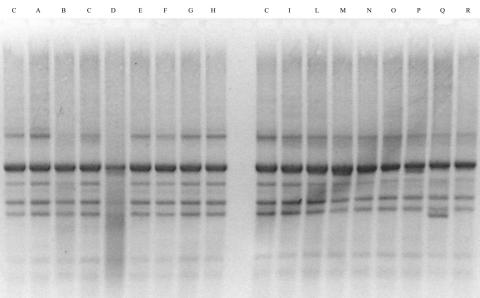

Rep-PCR strain-specific profiles of yogurt cultures and fecal isolates are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Strain-specific Rep-PCR detection of orally administered L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in fecal samples from subjects who consumed yogurt. Isolates were previously confirmed to belong to the L. delbrueckii group by species-specific PCR. Lanes C, profile of orally administered L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus; lanes A to H, profiles of isolates obtained on day 2 in trial 2; lanes I to R, profiles of isolates obtained on day 7 in trial 2. Lanes D and Q were not considered comparable to controls.

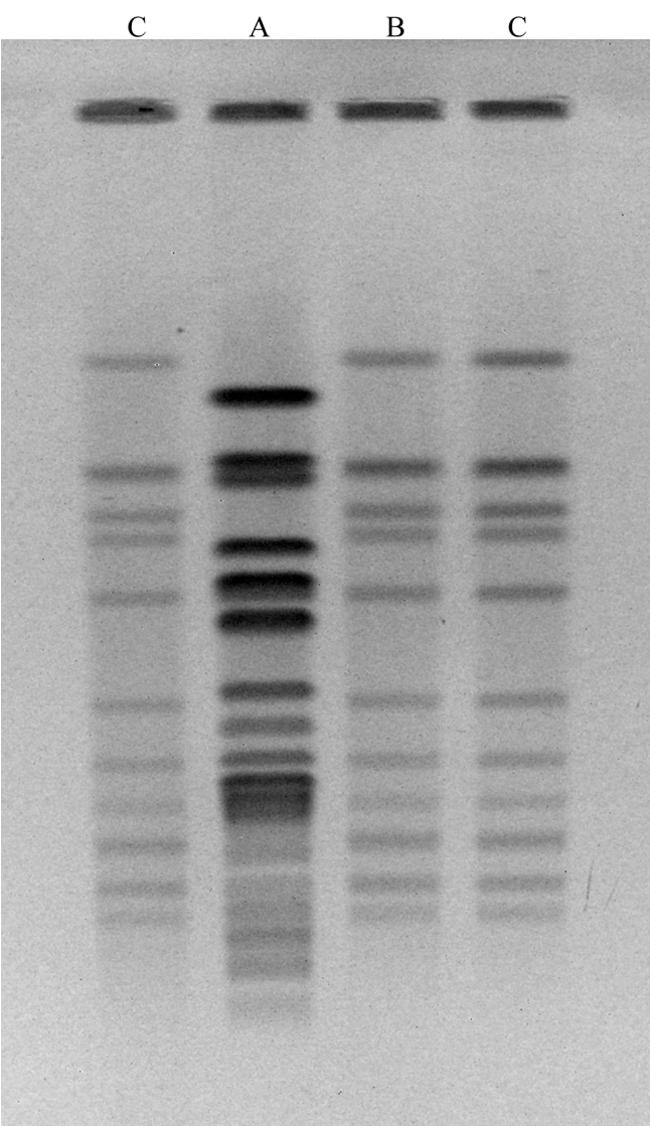

Molecular identification led to accurate detection of an orally administered Streptococcus strain in only one subject on day 7, despite the fact that another colony was recognized as an S. thermophilus colony by the PCR approach. Figure 2 shows that the orally administered S. thermophilus strain and the strain isolated from one volunteer were identical, while S. thermophilus isolated from another volunteer in trial 2 had a clearly different PFGE profile.

FIG. 2.

Strain-specific identification of orally administered S. thermophilus by PFGE analysis of two colonies from day 7 samples (trial 2) (lanes A and B) previously identified as belonging to S. thermophilus by species-specific PCR. The PFGE profile in lane B is identical to the profile for the orally administered strain in lanes C.

After 2 days of treatment, the recovery of orally administered L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in trial 2 was significantly greater than the recovery of orally administered L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in trial 1 (Table 2), which confirmed the contribution of m-RSMA to refinement of the microbiological approach used to assess the survival of the yogurt culture. The viability of orally administered L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus during passage through the gastrointestinal tract of humans was therefore confirmed, as described by Mater et al. (22), who recovered viable S. thermophilus and L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus from feces of healthy volunteers fed 375 g of yogurt per day. These conclusions were in contrast with the conclusions of Del Campo et al. (9), who reported consistently negative results for detection of plate colonies of yogurt bacteria from fecal samples of 114 volunteers, even if there were many positive results following hybridization of fecal DNA with species-specific probes. In this case, fecal specimens were plated onto media with poor selective properties, like MRS and M17, and plates were incubated in nonstringent conditions (37°C for thermophilic lactic acid bacteria), which resulted in growth of a background intestinal microflora that masked Streptococcus- and Lactobacillus-like colonies, particularly at low dilutions. Therefore, the presence of orally administered strains could have been underestimated.

In our study, S. thermophilus was retrieved from only one volunteer on day 7, but we cannot exclude the possibility that a prolonged ingestion period or a larger amount of ingested yogurt, as described by Mater et al. (22), could positively affect the rate of S. thermophilus recovery from fecal samples. However, several authors have shown that S. thermophilus suffers from the environmentally adverse gastric conditions (9, 26).

A recent report (4) described detection and enumeration of S. thermophilus from stool samples of 10 healthy subjects and 10 patients with irritable bowel syndrome, half of whom were treated with 250 g of yogurt per day and half of whom were treated with a probiotic pharmaceutical preparation. The thermophilic streptococci in feces were quantified by the authors using primers ThI and ThII (30), which we also tested in order to monitor the reliability of this species-specific primer pair. Our results confirmed that primers ThI and ThII could not discriminate between S. thermophilus and S. salivarius, as previously described by Tilsala-Timisjarvi and Alatossava (30). Species-specific PCR amplification performed with primers ThI and ThII could lead to incorrect results and, together with the lack of subsequent strain-specific recognition, could easily explain the retrieval of thermophilic streptococci in fecal samples described by Brigidi et al. (4). These observations confirm that assessment of yogurt culture survival in the human gut requires reliable molecular tools, such as PCR primers for species- and strain-specific identification of orally administered strains.

Since recently there have been conflicting reports, several authors are still debating the probiotic properties of traditional yogurt starters. Probiotic traits are currently considered to be strictly strain specific (29); therefore, the use of strain-specific molecular approaches is very relevant to the study of the survival and effects of yogurt starters on host health.

Moreover, the ability to survive transit through the gastrointestinal tract, the ability to reach the distal tract in a viable form, and the ability to be recovered from feces by culture methods are unequivocally considered key features for a probiotic. These considerations led us to focus on accurate strain-specific retrieval of viable yogurt cultures in fecal samples, while other authors failed to consider this aspect (9).

In conclusion, we confirmed that yogurt bacteria, especially L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, can be retrieved from feces of healthy individuals after a few days of ingestion of commercial yogurt. Moreover, our results indicate that very careful setup of the analytic procedures can dramatically improve the reliability of studies of the survival of yogurt starters.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adolfsson, O., S. N. Meydani, and R. M. Russell. 2004. Yogurt and gut function. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80:245-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldinucci, C., L. Bellussi, G. Monciatti, G. C. Passàli, L. Salerni, D. Passàli, and V. Bocci. 2002. Effects of dietary yoghurt on immunological and clinical parameters of rhinopathic patients. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 56:1155-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bezkorovainy, A. 2001. Probiotics: determinants of survival and growth in the gut. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 73(Suppl. 2):399S-405S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brigidi, P., E. Swennen, B. Vitali, M. Rossi, and D. Matteuzzi. 2003. PCR detection of Bifidobacterium strains and Streptococcus thermophilus in feces of human subjects after oral bacteriotherapy and yogurt consumption. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 81:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell, C. G., B. P. Chew, L. O. Luedecke, and T. D. Shultz. 2000. Yogurt consumption does not enhance immune function in healthy premenopausal women. Nutr. Cancer 37:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlsson, P., and D. Bratthall. 1985. Secretory and serum antibodies against Streptococcus lactis, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Lactobacillus bulgaricus in relation to ingestion of fermented milk products. Acta Odontol. Scand. 43:147-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conway, P. L., S. L. Gorbach, and B. R. Goldin. 1987. Survival of lactic acid bacteria in the human stomach and adhesion to intestinal cells. J. Dairy Sci. 70:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cross, M. L., L. M. Stevenson, and H. S. Gill. 2001. Anti-allergy properties of fermented foods: an important immunoregulatory mechanism of lactic acid bacteria? Int. Immunopharmacol. 1:891-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Campo, R., D. Bravo, R. Canton, P. Ruiz-Garbajosa, R. Garcia-Albiach, A. Montesi-Libois, F.-J. Yuste, V. Abraira, and F. Baquero. 2005. Scarce evidence of yogurt lactic acid bacteria in human feces after daily yogurt consumption by healthy volunteers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:547-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drake, M., C. L. Small, S. D. Kemet, and B. G. Swanson. 1996. Rapid detection and identification of Lactobacillus spp. in dairy products by using the polymerase chain reaction. J. Food Prot. 59:1031-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fioramonti, J., V. Theodorou, and L. Bueno. 2003. Probiotics: what are they? What are their effects on gut physiology? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 17:711-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greene, J. D., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1994. Factors involved in adherence of lactobacilli to human Caco-2 cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4487-4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarner, F., G. Perdigon, G. Corthier, S. Salminen, B. Koletzko, and L. Morelli. 2005. Should yoghurt cultures be considered probiotic? Br. J. Nutr. 93:783-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halpern, G. M., K. G. Vruwink, J. Van de Water, C. L. Keen, and M. E. Gershwin. 1991. Influence of long-term yoghurt consumption in young adults. Int. J. Immunother. 7:205-210. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitazawa, H., H. Watanabe, T. Shimosato, Y. Kawai, T. Itoh, and T. Saito. 2003. Immunostimulatory oligonucleotide, CpG-like motif exists in Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus NIAI B6. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 85:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Labayen, I., L. Forga, A. Gonzalez, I. Lenoir-Wijnkoop, R. Nutr, and J. A. Martinez. 2001. Relationship between lactose digestion, gastrointestinal transit time and symptoms in lactose malabsorbers after dairy consumption. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 15:543-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lerebours, E., N. C. N’Djitoyap, A. Lavoine, M. F. Hellot, J. M. Antoine, and R. Colin. 1989. Yogurt and fermented-then-pasteurized milk: effects of short-term and long-term ingestion on lactose absorption and mucosal lactase activity in lactase-deficient subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 49:823-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lick, S., E. Brockmann, and K. J. Heller. 2000. Identification of Lactobacillus delbrueckii and subspecies by hybridization probes and PCR. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 23:251-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lick, S., M. Keller, W. Bockelmann, and K. J. Heller. 1996. Rapid identification of Streptococcus thermophilus by primer-specific PCR amplification based on its lacZ gene. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 19:74-77. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marteau, P., B. Flourie, P. Pochart, C. Chastang, J. F. Desjeux, and J. C. Rambaud. 1990. Effect of the microbial lactase (EC 3.2.2.23) activity in yoghurt on the intestinal absorption of lactose: an in vivo study in lactase-deficient humans. Br. J. Nutr. 64:71-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martini, M. C., D. Kukielka, and D. A. Savaiano. 1991. Lactose digestion from yogurt: influence of a meal and additional lactose. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 53:1253-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mater, D. D. G., L. Bretigny, O. Firmesse, M.-J. Flores, A. Mogenet, J.-L. Bresson, and G. Corthier. 2005. Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus survive gastrointestinal transit of healthy volunteers consuming yoghurt. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 250:185-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meydani, S. N., and W.-K. Ha. 2000. Immunologic effects of yogurt. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 71:861-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mora, D., M. G. Fortina, C. Parini, G. Ricci, M. Gatti, G. Giraffa, and P. L. Manachini. 2002. Genetic diversity and technological properties of Streptococcus thermophilus strains isolated from dairy products. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93:278-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Sullivan, T. F., and G. F. Fitzgerald. 1998. Comparison of Streptococcus thermophilus strains by pulsed field gel electrophoresis of genomic DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 168:213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedrosa, M. C., B. B. Golner, B. R. Goldin, S. Barakat, G. E. Dallal, and R. M. Russell. 1995. Survival of yogurt-containing organisms and Lactobacillus gasseri (ADH) and their effect on bacterial enzyme activity in the gastrointestinal tract of healthy and hypochlorhydric elderly subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 61:353-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pochart, P., O. Dewit, J. F. Desieux, and P. Bourlioux. 1989. Viable starter cultures, beta-galactosidase activity, and lactose in duodenum after yoghurt ingestion in lactase-deficient humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 49:828-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sachs, G., D. L. Weeks, K. Melchers, and D. R. Scott. 2003. The gastric biology of Helicobacter pylori. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65:349-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senok, A. C., A. Y. Ismaeel, and G. A. Botta. 2005. Probiotics: facts and myths. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11:958-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tilsala-Timisjarvi, A. T., and T. Alatossava. 1997. Development of oligonucleotide primers from the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic sequences for identifying different dairy and probiotic lactic acid bacteria by PCR. Int. Food Microbiol. 35:49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van der Water, J., C. L. Keen, and M. E. Gershwin. 1999. The influence of chronic yogurt consumption on immunity. J. Nutr. 129(Suppl. 7):1492S-1495S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Versalovic, J., M. Schneider, F. J. de Brujin, and J. R. Lupski. 1994. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol. Cell. Biol. 5:25-40. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Von der Weid, T., A. Donnet-Hughes, S. Blum, E. J. Schiffrin, J. R. Neeser, and A. Pfeifer. 2001. Scientific thoroughness of human studies showing immune-stimulating properties of yogurt. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 73:133-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watanabe, T., H. Shimohashi, Y. Kawai, and M. Mutai. 1981. Studies on streptococci. I. Distribution of fecal streptococci in man. Microbiol. Immunol. 25:257-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wheeler, J. G., M. L. Bogle, S. J. Shema, M. A. Shirrell, K. C. Stine, A. J. Pittler, A. W. Burks, and R. M. Helm. 1997. Impact of dietary yogurt on immune function. Am. J. Med. Sci. 313:120-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]