Abstract

The committing step in Met and S-adenosyl-l-Met (SAM) synthesis is catalyzed by cystathionine γ-synthase (CGS). Transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing CGS under control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter show increased soluble Met and its metabolite S-methyl-Met, but only at specific stages of development. The highest level of Met and S-methyl-Met was observed in seedling tissues and in flowers, siliques, and roots of mature plants where they accumulate 8- to 20-fold above wild type, whereas the level in mature leaves and other tissues is no greater than wild type. CGS-overexpressing seedlings are resistant to ethionine, a toxic Met analog. With these properties the transgenic lines resemble mto1, an Arabidopsis, CGS-mutant inactivated in the autogenous control mechanism for Met-dependent down-regulation of CGS expression. However, wild-type CGS was overexpressed in the transgenic plants, indicating that autogenous control can be overcome by increasing the level of CGS mRNA through transcriptional control. Several of the transgenic lines show silencing of CGS resulting in deformed plants with a reduced capacity for reproductive growth. Exogenous feeding of Met to the most severely affected plants partially restores their growth. Similar morphological deformities are observed in plants cosuppressed for SAM synthetase, even though such plants accumulate 250-fold more soluble Met than wild type and they overexpress CGS. The results suggest that the abnormalities associated with CGS and SAM synthetase silencing are due in part to a reduced ability to produce SAM and that SAM may be a regulator of CGS expression.

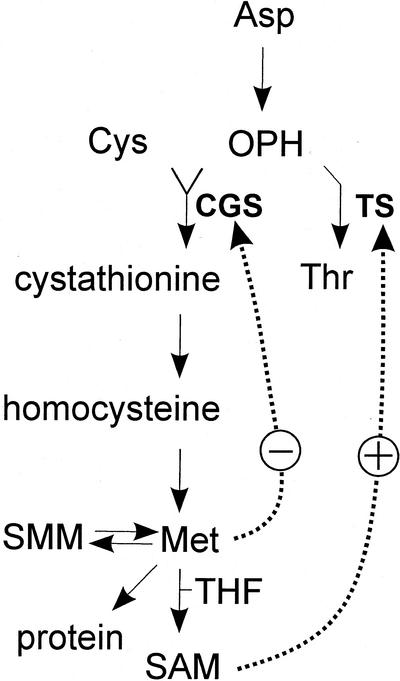

Met is derived from Asp as are the amino acids Lys, Thr, and Ile. The committing step in Met synthesis occurs when the side chain of O-phosphohomoserine (OPH) condenses with the thiol group of Cys to form cystathionine (Fig. 1), an irreversible reaction catalyzed by CGS (EC 4.2.99.9). Cystathionine is cleaved to form homocysteine, which is then methylated with 5-methyltetrahydrofolate to form Met. The major metabolic fates of Met include its incorporation into protein, adenosylation to form SAM, and methylation to form S-methyl Met (SMM) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Pathway for synthesis of Met, SAM, and Thr. The pathway is as described in the text. SMM, S-methyl-Met; THF, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; SAM, S-adenosyl-l-Met; CGS, cystathionine γ-synthase; TS, Thr synthase. Solid arrows refer to enzymatic steps and dotted arrows refer to regulatory steps. The arrow from Asp to OPH represents four enzymatic steps.

CGS competes with TS for OPH, their common substrate. Thus, TS may exert some control over the rate with which OPH is channeled toward Met (Bartlem et al., 2000; Fig. 1). TS is allostrically regulated by SAM (Curien et al., 1998) suggesting that Met synthesis could influence TS activity. Even so, several lines of evidence indicate that CGS controls the rate of Met synthesis. CGS activity decreases when Met is fed to the aquatic angiosperm Lemna paucicostata and increases when Met synthesis is blocked by inhibition of aspartokinase, the first enzyme in the biosynthesis of the Asp family of amino acids (Thompson et al., 1982). In the Arabidopsis mutant mto1, CGS is overexpressed, resulting in overaccumulation of soluble Met (Inaba et al., 1994; Chiba et al., 1999). Finally, antisense-RNA repression of CGS expression results in growth deformities stemming from an inability to synthesize Met (Gakiére et al., 2000; Kim and Leustek, 2000).

CGS expression may be regulated in Arabidopsis by an autogenous mechanism, revealed through analysis of the mutant mto1 (Chiba et al., 1999). In wild-type Arabidopsis, Met or a metabolite thereof down-regulates CGS enzyme expression (Fig. 1) through a post-translational mechanism that acts by destabilizing CGS mRNA. In mto1, a point mutation in exon 1 of the CGS gene abolishes the Met-dependent destabilization of CGS mRNA causing the enzyme level and soluble Met level to rise. mto1 was isolated by selection for Arabidopsis mutants that are resistant to ethionine, a toxic Met analog. Ethionine-resistance arises from overaccumulation of soluble Met.

In this study a transgenic approach was used to study the role that CGS protein abundance plays in controlling the level of free Met in Arabidopsis. The results show that transcriptional up-regulation of CGS causes accumulation of soluble Met and SMM, but only in specific tissues and stages of development. The results also show that transcriptional up-regulation of CGS can overcome the post-transcriptional mechanism controlling CGS expression. Cosuppression of CGS causes pronounced morphological aberrations and physiological changes that resemble those observed in Arabidopsis plants in which SAM synthetase (SAMS) is cosuppressed. Comparative analysis of CGS and SAMS-silenced plants suggests that SAM may be a regulator of CGS expression and that SAM deficiency may cause the morphological and physiological aberrations.

RESULTS

Isolation and Initial Characterization of Arabidopsis Lines with Altered Expression of CGS

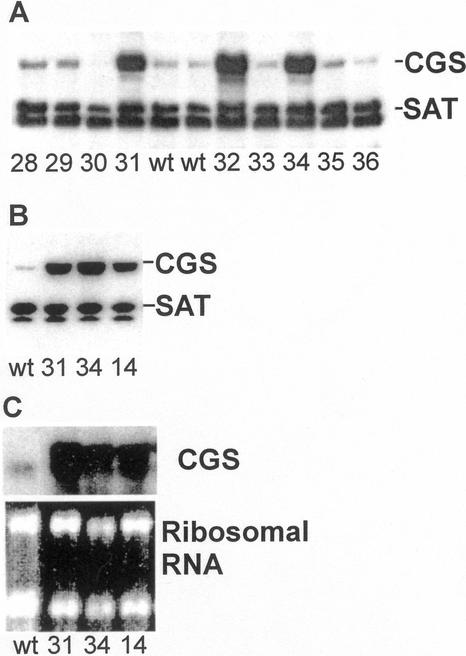

Transgenic Arabidopsis plants were isolated from transformations with a construct intended to produce stable overexpression of CGS. A representative blot of leaf tissue from primary transformants analyzed for CGS protein level by immunoblotting shows that transgenic plants were isolated with a diversity of CGS levels in leaf tissue ranging from high-level expression (lines 31, 32, and 34) to plants from which CGS protein could not be detected (line 30; Fig. 2A). Reaction with an antibody against Ser acetyltransferase (SAT), an enzyme in the Cys biosynthesis pathway, illustrates that SAT, which is two biosynthetic steps before CGS, is unaffected in the transgenic plants. In total, 38 Kan-resistant plants were analyzed. Five showed high-level CGS expression (lines 14, 26, 31, 32, and 34) and many more showed an intermediate level of expression. In six of the primary transformants CGS protein could not be detected by immunoblotting (lines 16, 19, 20, 21, 23, and 30). The CGS-overexpression level was generally stable in the progeny of primary transformants up to the fourth generation, the last one that was analyzed. There were, however, exceptions that will be detailed later in this paper.

Figure 2.

Blot analysis of CGS expression. A, Immunoblot of primary transgenic plants. The transgenic plants were selected on agar medium with 50 μg mL−1 Kan for 7 d and then transferred to potting mix and grown for 30 d further. Ten micrograms of leaf protein was analyzed. B, Immunoblot of fourth generation homozygous CGS transgenic plants. The plants were grown in potting mix for 27 d. Ten micrograms of leaf protein was analyzed. C, RNA blot of fourth generation homozygous CGS transgenic plants grown as described in B. Ten micrograms of leaf RNA was analyzed for wild type and 5 μg for the transgenics. For all panels the transgenic plant tracking numbers or line names (wt, wild type) are indicated below the blots. Immunoblots were reacted at once with two antisera, one against CGS and the other against SAT. SAT serves as a protein loading control and it can be used in combination with the CGS antiserum because neither one interferes with the binding of the other to its specific antigen. CGS migrates at approximately 53 kD and SAT at approximately 39 kD. The band appearing below SAT is attributed to a reaction of the secondary antibody.

Three transgenic lines were chosen for further analysis (lines 14, 31, and 34), each from an independently transformed plant. The CGS construct was detected in each of the lines by PCR analysis (not shown). RNA and immunoblot analysis showed that CGS is overexpressed in the leaves of 27-d-old plants (Fig. 2, B and C). Based on analysis of the intensity of the signal from the immunoblot CGS protein is 6- to 9-fold more abundant in the transgenic lines analyzed than in wild type. CGS enzyme activity measurements (CGS activity was measured with DPH as substrate) gave similar results. Lines 14, 31, and 34, respectively, showed 0.87 ± 0.06, 2.05 ± 0.07, and 1.10 ± 0.17 nmol min−1 mg−1 protein compared with an activity of 0.12 ± 0.04 for wild type. The intensity of hybridization signals from the RNA blot showed that CGS mRNA is 11- to 23-fold more abundant in the transgenics.

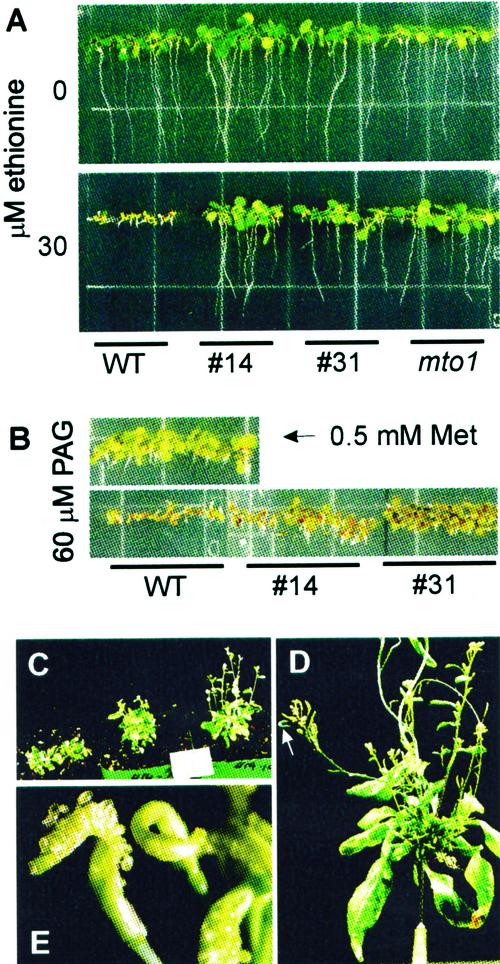

Plants That Overexpress CGS Are Resistant to Two Different Met-Pathway Toxins

Plants that overexpress CGS are phenotypically normal compared with wild type. The three lines chosen for detailed analysis can be visually distinguished from wild type by their resistance to ethionine and dl-propargylglycine (PAG). Ethionine resistance for two of them, lines 14 and 31 are shown in Figure 3A compared with mto1. Ethionine is a toxic Met analog and resistance can be overcome by overproduction of soluble Met (Inaba et al., 1994; Bartlem et al., 2000). This result indicates that CGS overexpression has probably resulted in Met overproduction in Arabidopsis seedlings.

Figure 3.

Resistance of CGS-overexpressing plants to ethionine or PAG, and phenotype of CGS-cosuppressed plants. A, Resistance to ethionine; B, resistance to PAG; C, response of plants that show CGS cosuppression early in development to exogenously applied Met; D, morphology of a plant in advanced stage of CGS cosuppression at the reproductive stage of development (the arrow indicates an example of a deformed silique); and E, close-up photograph of a deformed silique like that indicated by the arrow in D. Ethionine and PAG resistance were performed on fourth generation homozygous progeny of the indicated primary transgenic plants. The plants were grown on the indicated ethionine or PAG concentration. The reversal of PAG-induced growth inhibition by Met is shown in B. The plants shown in C are the third generation progeny from primary transformant 14 grown for 35 d in soil. The two plants in the pot on the left were not fed Met. The plants in the two pots on the right of the photograph were watered for 14 d with a nutrient solution containing 5 mm Met. The plant shown in D is a third-generation progeny of primary transgenic 14 grown for 45 d. The silique in E is from a third generation progeny of primary transformant 31 grown for 50 d.

PAG irreversibly inhibits CGS after binding to the enzyme active site (Johnston et al., 1979; Datko and Mudd, 1982; Ravanel et al., 1995). The specificity of this inhibitor is illustrated in Figure 3B. PAG at 60 μm inhibits the growth of wild-type Arabidopsis, however, growth is not inhibited if PAG is co-applied with 0.5 mm Met. All the CGS-overproducing lines showed resistance to PAG, as did the mto1 mutant (not shown). Although PAG resistance in plants has never been reported before, it could theoretically arise from overproduction of active CGS, which would effectively titrate away the inhibitor by providing an excess of PAG binding sites.

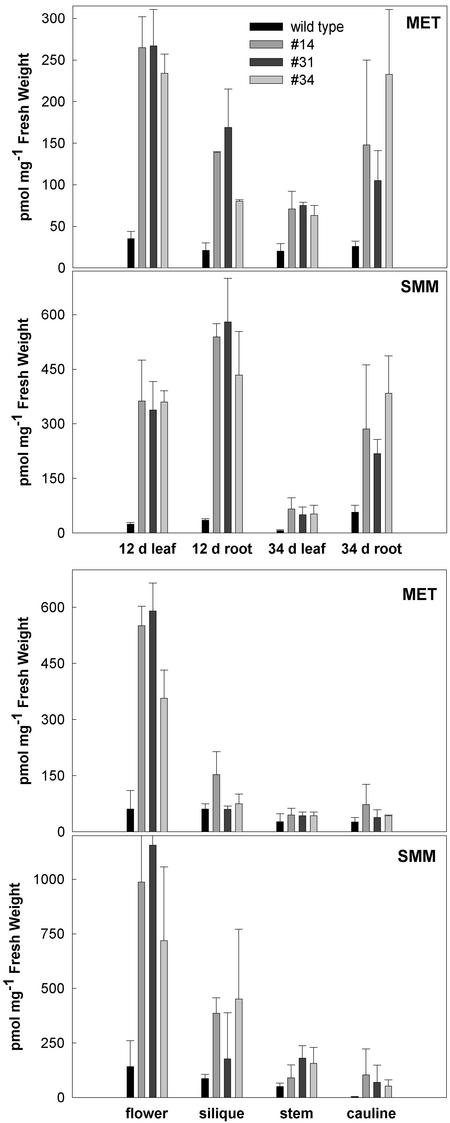

Plants That Overexpress CGS Accumulate Free Met and SMM

Analysis of soluble amino acids revealed that Met and SMM accumulate in the CGS-overexpressing plants, but their level is strongly dependent on the developmental stage and organ (Fig. 4). The highest levels occur in the leaf and root of seedlings and in the root and flowers of mature plants. The accumulation of soluble SMM is more pronounced than is the accumulation of Met. The high accumulation of soluble Met and SMM in seedlings correlates with the resistance of seedlings to ethionine (Fig. 3A). As the CGS-overexpressing transgenic plants begin to flower, the level of Met and SMM declines in leaf tissue. The level of these metabolites in roots is maintained, although the variation between plant samples increases. The level of Met and SMM in flowers is markedly greater than in wild-type flowers. In developing siliques, the inflorescence stem, and cauline leaves, Met and SMM are slightly elevated compared with wild type. As the plants progress through the flowering stage of development the level of Met and SMM in the leaf of transgenic plants declines further and is nearly indistinguishable from wild type, whereas the level remains high in flowers (not shown).

Figure 4.

Soluble Met and SMM levels in tissues of wild-type and CGS-overexpressing plants. Plants of 12 d age were grown on agar medium. Plants of 34 d age were grown hydroponically. Flowers, siliques, stems, and cauline leaves were harvested from 38-d-old plants grown in potting mix. The identities of bars are as indicated in the inset of the top graph.

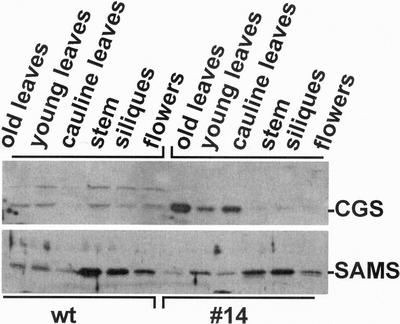

CGS Is Not Overproduced Equally in All the Organs of Transgenic Plants

Although it is expressed under the control of the 35S promoter, CGS is not uniformly overproduced throughout the plant. The immunoblot in Figure 5 shows it is strongly overproduced in young and older rosette leaves and in cauline leaves. Its level in stem, siliques, flowers, and roots (not shown) of the transgenic plants is far lower than in leaves. By comparison, SAMS is expressed to high levels in the stem and siliques, as has been previously reported (Peleman et al., 1989), and there is no difference in SAMS level between wild-type and CGS transgenic plants. Organ-specific CGS expression was similar in lines 14, 31, and 34, indicating that the expression pattern is a general feature of the transgenic plants. It is noteworthy that in flowering stage plants, the level of Met and SMM is inversely correlated with the level of CGS. The highest levels of Met and SMM occur in flowers and roots where CGS level is lowest, compared with leaves where the CGS level is high, but Met and SMM are low. By contrast, in the tissues of young plants CGS level correlated positively with the level of Met and SMM (not shown). It is important to note that plants of normal morphology were used for the analysis of CGS expression described here.

Figure 5.

Immunoblot analysis of CGS and SAMS levels in various tissues from transgenic Arabidopsis that overexpress CGS. Plants from line 14 or wild type were grown for 45 d in potting mix. Immunoblotting was carried out on proteins from older, fully expanded leaves, young, immature leaves, cauline leaves, floral stem, siliques, and flowers harvested approximately at anthesis. The samples are described above and below the blots. Five micrograms of protein were analyzed for samples of wild type and 0.5 μg of samples from transgenic line 14.

Silencing of CGS Is Associated with Growth and Metabolic Abnormalities

Five of the primary transgenic plants derived from transformation with the construct intended for CGS overexpression did not show immunodetectable CGS protein (e.g. plant 30 in Fig. 2). The growth of these individuals was severely stunted and they were unable to produce inflorescences. The plants developed many, very small leaves, resulting from proliferation of numerous apical shoots, an indication that they may have reduced apical dominance. Application of Met as an addition to the watering solution stimulated vegetative and reproductive growth, although a completely normal morphology was not restored. However, with Met feeding, the plants were able to set viable seeds, which they could not without Met feeding. The seeds from Met-rescued plants in the second and later generations produced both normal, CGS-overexpressing, and abnormal, CGS-silenced progeny indicating that CGS silencing is unstable. The primary transgenic plants that initially showed CGS-overexpression also produced growth-stunted progeny that could be rescued by Met-feeding. A typical example from line 14 is shown in Figure 3C. Met was not applied to the two plants in the pot on the left, whereas Met was applied to the plants in the two pots on the right of the photograph. The growth of several inflorescences is visible in the Met-fed plants. The frequency with which severely stunted, CGS-silenced individuals were produced from a given line varied widely from one generation to the next and there was significant variation between transgenic lines. The simplest explanation for the phenotype of these plants is that silencing of CGS expression resulted in an inability to synthesize sufficient Met, or a metabolite thereof, for growth and that CGS silencing occurs spontaneously in response to epigenetic factors.

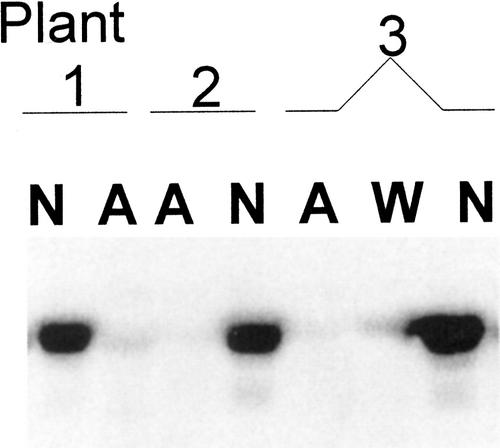

CGS cosuppression and associated morphological aberrations were also observed later in development. Such individuals were morphologically normal and overexpressed CGS until flowering had begun. Then, CGS silencing would occur in localized sectors, followed by a progressive advance of co-suppression throughout the plant and also in tissues that were previously normal. At an intermediate stage, it was possible to identify individual plants with both normal and abnormal organs. The immunoblot in Figure 6 shows that CGS is overexpressed in normal rosette leaves of such plants, but is cosuppressed in the abnormal rosette leaves. Silencing of CGS in such plants appeared to be spontaneous, occurring in only some progeny from a given line, and the frequency varied widely from one generation to the next and between transgenic lines. In some lines it was not at all observed.

Figure 6.

Immunoblot analysis of CGS level in leaf extracts from transgenic Arabidopsis plants showing normal (N) and abnormal (A) morphology compared with wild type (W). Abnormal is defined in the text. Plants from line 14 were grown in potting mix for 45 d. Five micrograms of protein was analyzed.

A typical example of a plant at an advanced stage of CGS silencing is shown in Figure 3D. This particular individual grew normally and had produced a normal inflorescence at the time that the first symptoms of CGS silencing became evident. The normal inflorescence was cropped from the top of the photograph to focus on the aberrant morphology. At the time the photograph was taken all the leaves of this individual, which were initially of normal morphology, had became curled and developed small chlorotic patches. A second flush of abnormal inflorescences were produced, characterized by tightly clustered flowers and siliques, suggesting that apical dominance was lost and that elongation of the inflorescences had been curtailed. The abnormal development of siliques was particularly striking. During the early stages of growth the siliques split open, exposing the young ovules (Fig. 3E). The rupture would occur in the ovary wall, not at the dehiscence zone, and it appeared to arise from precocious enlargement of the ovules without a compensatory growth of the ovary wall. In other cases siliques would not split, but the enlarged ovules would produce a distinctive bumpy surface and curled structure as indicated by the arrow in the photograph of Figure 3D.

Soluble amino acid analysis revealed extensive changes throughout plants in the advanced stages of CGS cosuppression. The levels of Met and SMM in the leaves and floral stem of normal plants is comparable with wild-type and CGS-overexpressing plants (Table I). However, Thr is 3.3- to 8.3-fold greater in the CGS-cosuppressed plants than in wild type, and total amino acids are up to 3.8-fold greater (Table I). The amino acids contributing to the overall increase in total amino acids are shown in Table II. From these results it is evident that a wide range of amino acids contribute to the increase.

Table I.

Amino acid content in transgenic Arabidopsis that overexpress or cosuppress CGS

| Sample | Amino Acid Content

|

Total Amino Acid Relative Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met | SMM | Thr | ||

| pmol mg−1 fresh wt | ||||

| Leaf wild type | 9 ± 4 | 0 | 407 ± 98 | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

| Leaf #31cs | 7 ± 7 | 0 | 2964 ± 1346 | 3.8 ± 0.7 |

| Leaf #34cs | 10 ± 2 | 0 | 1820 ± 382 | 3.0 ± 0.9 |

| Leaf #34oe | 27 | 0 | 365 | 1.2 |

| Stem wild type | 9 ± 7 | 5 ± 9 | 1298 ± 515 | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

| Stem #31cs | 11 ± 1 | 0 | 5018 ± 1655 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

| Stem #34cs | 6 ± 4 | 0 | 7091 ± 3349 | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

| Stem #34oe | 43 | 15 | 1082 | 1.3 |

| Silique wild type | 10 ± 5 | 79 ± 29 | 1310 ± 365 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| Silique #31cs | 32 ± 37 | 80 ± 77 | 4272 ± 514 | 3.1 ± 0.8 |

| Silique #34cs | 67 ± 1 | 171 ± 54 | 10985 ± 792 | 3.9 ± 0.8 |

| Silique #34oe | 765 | 1592 | 1617 | 1.1 |

Soluble amino acids were measured in tissues from 52-d-old plants. The samples from transgenic plants were taken from individuals showing CGS cosuppression (cs), and a plant from line 34 that overexpresses CGS (oe). The averages ± sd of three independent plants are shown with the exception of 34, which is a measurement from a single plant. For plant-to-plant variation for line 34, readers are referred to the data in Figure 4, which was obtained from 38-d-old plants. Differences between the value presented here for 34 and in Figure 4 may be due to differences in plant age. Total amino acid content represents the relative level calculated as the sum of all peak areas from chromatograms divided by the fresh weight of the plant sample. Amino acids were measured using the AQC method.

Table II.

Changes in amino acid content of CGS cosuppressed Arabidopsis

| Fold Increase | Plant Line and Organ

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 Leaf | 34 Leaf | 31 Silique | 34 Silique | |

| 1 | Met | Met | Asn/Ser | Asn/Ser |

| Asp | Gln/His | |||

| Gln/His | Glu | |||

| Glu | ||||

| 2 to 4 | Gly | Ala | Ala | Ala |

| Asp | Arg | Asp | ||

| Gln/His | Gly | Gly | ||

| Gly | Leu | Met | ||

| Met | ||||

| Pro | ||||

| Thr | ||||

| Tyr | ||||

| Val | ||||

| 5 to 9 | Ala | Asn/Ser | Ile | Arg |

| Asn/Ser | Glu | Leu | ||

| Asp | Ile | Phe | ||

| Glu | Leu | Thr | ||

| Leu | Lys | Val | ||

| Lys | Phe | |||

| Phe | Thr | |||

| Tyr | Tyr | |||

| Val | Val | |||

| 10 to 20 | Arg | Arg | Lys | Ile |

| Gln/His | Pro | Phe | Lys | |

| Ile | Pro | |||

| Pro | Tyr | |||

| Thr | ||||

The fold increase in amino acid content is given for leaf and silique from lines 31 and 34. The Asn and Ser peaks are not resolved on the chromatograph nor are the Gln and His peaks. Cys and Trp peaks could not be identified due to interference from unidentified compounds.

The Morphology of CGS-Silenced Plants Resembles That Associated with SAMS Silencing

During the course of this study, it became evident that the morphology resulting from CGS silencing is remarkably similar to that of transgenic Arabidopsis cosuppressed for SAMS. Preliminary characterization of SAMS silencing in Arabidopsis has been reported by Boerjan (1993) and de Carvalho et al. (1994) and is in many respects similar to the effects of SAMS cosuppression in tobacco (Boerjan et al., 1994). Transgenic Arabidopsis lines showing cosuppression for CGS and SAMS were grown side by side for a more detailed comparison. The phenomena of CGS and SAMS cosuppression share the properties of being sporadic, hyper-variable, and localized to sectors on a single plant. The plants in which SAMS becomes cosuppressed early in development are severely stunted, produce numerous apical shoots, and are unable to flower. These are termed the MUT3 morphotype using the nomenclature of Boerjan (1993) and de Carvalho et al. (1994). MUT3 plants are nearly indistinguishable from plants in which CGS becomes cosuppressed early in development. A major difference is that the growth of SAMS cosuppressed plants cannot be restored by exogenous application of Met. Plants that develop SAMS cosuppression later in development produce curled, chlorotic leaves, and distorted siliques resulting from early enlargement of ovules, similar to plants where CGS becomes silenced later in development. These are termed the MUT2 morphotype (Boerjan, 1993; de Carvalho et al., 1994). Plants that overexpress SAMS are morphologically indistinguishable from wild type and are termed the MUT1 morphotype (Boerjan, 1993; de Carvalho et al., 1994).

Silencing of SAMS Causes CGS Overexpression and Accumulation of Met, SMM, and Other Amino Acids

In considering the significant morphological similarities associated with SAMS and CGS silencing it is noteworthy that these enzymes are metabolic neighbors in the pathway for SAM synthesis. It was, therefore, of interest to compare the physiological properties of SAMS-silenced plants with those that overexpress SAMS and wild type. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that the SAMS protein is overproduced in the leaves of the MUT1 morphotype and is reduced in the MUT2 and MUT3 morphotypes (Fig. 7), as has previously been shown by SAMS activity measurements (Boerjan, 1993; de Carvalho et al., 1994). In contrast, CGS is overexpressed in MUT2 and MUT3, whereas its expression is slightly lower in MUT1 compared with wild type. Measurement of CGS enzyme activity in the leaves of MUT3 plants revealed that it is 0.91 ± 0.03 nmol min−1 mg−1 protein, compared with wild-type activity (0.33 ± 0.06), indicating that MUT3 plants have approximately 3-fold higher CGS activity than do wild-type plants. In contrast, SAT expression is unaffected.

Figure 7.

Blot analysis of leaf tissue from plants transformed with the SAMS construct. The plants were grown for 35 d in potting mix, and leaf samples from two individual plants of each morphotype were analyzed along with wild type and the mto1 mutant. A. Immunoblots with the indicated antisera. B, RNA blot lane 2 and 3, line 27; lane 4 and 5, line 37. The samples are identified above the blots.

Amino acid analysis revealed that the level of soluble Met and SMM are similar in wild type and in MUT1, but these metabolites accumulate to high levels in MUT2 and MUT3 (Table III). This property is in contrast to CGS-silenced plants, which do not accumulate Met and SMM. However, Thr and total amino acids are markedly increased (Table III). The amino acids contributing to the increase are listed in Table IV. The bulk of the increase is attributed to Arg, Pro, Met, and Lys, which are 145- to 568-fold more abundant than in wild-type or MUT1 plants.

Table III.

Amino acid content in transgenic Arabidopsis that overexpress or cosuppress SAMS

| Sample | Amino Acid Content

|

Total Amino Acid Relative Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met | SMM | Thr | ||

| pmol mg−1 fresh wt | ||||

| Wild type | 12 ± 4 | 11 ± 2 | 702 ± 97 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| MUT1 27 | 15 ± 5 | 5 ± <1 | 581 ± 78 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| MUT1 37 | 17 ± 2 | 4 ± <1 | 783 ± 34 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| MUT2 27 | 1,962 ± 78 | n/d | 2,265 ± 160 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| MUT2 37 | 1,955 ± 106 | n/d | 2,130 ± 105 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| MUT3 27 | 2,086 ± 287 | 424 ± 83 | 2,856 ± 376 | 4.0 ± 1.0 |

| MUT3 37 | 2,967 ± 249 | 489 ± 48 | 3,343 ± 231 | 5.0 ± 1.0 |

Soluble amino acids were measured in the leaves of 44-d-old plants. The averages ± sd of three independent plants are shown. MUT1, -2, and -3 are morphotypes as described in the text derived from two different transgenic lines termed line 27 and line 37. Total amino acid content represents the relative level calculated as the sum of all peak areas from chromatograms divided by the fresh weight of the plant sample. n/d, Not determined. Amino acids were measured using the ninhydrin method. SMM was measured using the DMS release assay.

Table IV.

Changes in amino acid content of SAMS cosuppressed Arabidopsis

| Fold Increase | Plant Line and Morphotype

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 MUT2 | 27 MUT3 | 37 MUT2 | 37 MUT3 | |

| 1 | Ala | Asp | ||

| Asp | Glu | |||

| Glu | ||||

| Gly | ||||

| Phe | ||||

| Tyr | ||||

| 2 to 4 | Asn/Ser | Asp | Ala | Asp |

| Ile | Glu | Asn/Ser | Glu | |

| Leu | Tyr | Tyr | ||

| Thr | ||||

| Val | ||||

| 5 to 20 | Arg | Ala | Gln/His | Ala |

| Gln/His | Asn/Ser | Gly | Asn/Ser | |

| Gly | Ile | Gln/His | ||

| Phe | Leu | Gly | ||

| Thr | Phe | Leu | ||

| Tyr | Thr | Phe | ||

| Val | Val | Thr | ||

| Val | ||||

| 21 to 568 | Lys | Arg | Arg | Arg |

| Met | Gln/His | Lys | Ile | |

| Pro | Ile | Met | Lys | |

| Leu | Pro | Met | ||

| Lys | Pro | |||

| Met | ||||

| Pro | ||||

The fold increase in amino acid content is given for MUT2 and MUT3 morphotypes of SAMS lines 27 and 37. The Asn and Ser peaks are not resolved on the chromatograph nor are the Gln and His peaks. Cys and Trp peaks could not be identified due to interference from unidentified compounds.

DISCUSSION

The rationale for overexpressing CGS in transgenic Arabidopsis was to test whether this enzyme plays a role in regulation of Met synthesis, a hypothesis based upon both physiological (Thompson et al., 1982) and genetic (Chiba et al., 1999) evidence. The accumulation of soluble Met and SMM in the transgenic lines overexpressing CGS indicates that CGS is indeed a control point. The evidence from CGS transgenics, in combination with analysis of SAMS transgenic plants, produced insight into four additional points: (a) The observation that Met accumulation does not correlate with CGS level in a specific tissue indicates that the tissue concentration of soluble Met is controlled by factors other than the level of CGS activity; (b) the observation that CGS is not overproduced in some plant tissues, even though expression was transcriptionally deregulated from the transgene construct, suggests that a post-transcriptional mechanism may be involved in control of CGS expression; (c) the morphological similarity of CGS and SAMS-silenced plants suggests that the growth abnormalities are due in part to a reduced ability to produce SAM; and (d) the observation that CGS is overexpressed in SAMS-silenced plants provides indirect evidence that CGS expression may be controlled by SAM or some metabolite downstream of SAM. Each of these points will be individually addressed in the discussion that follows.

The leading hypothesis for the control of Met synthesis proposes that regulation occurs from the interplay between CGS and TS, two enzymes that compete for a common substrate, OPH (Giovanelli et al., 1980). In wild-type plants the level of Met and its metabolite SAM, control the partitioning of OPH. SAM activates TS (Curien et al., 1998), and Met or one of its metabolites represses CGS expression (Thompson et al., 1982; Chiba et al., 1999; Fig. 1). The finding reported here, that transcriptional up-regulation of CGS increases the soluble Met and SMM level in Arabidopsis, supports this hypothesis. Yet, CGS overexpression did not cause Thr to decline in proportion to the increase in Met and SMM, as might have been expected if CGS and TS compete for a fixed pool of OPH. This result suggests that the OPH pool is not fixed and that the rate of OPH synthesis may change in response to increased OPH utilization by CGS.

In young transgenic Arabidopsis tissues the level of CGS protein correlates with accumulation of soluble Met and SMM, however, this relationship does not hold for older plants. The levels of Met and SMM decline in leaves at the time that flowers are produced (Fig. 4). Although CGS is much lower in flowers, Met and SMM accumulate in them. A similar phenomenon occurs in roots of reproductive stage plants, in which CGS expression is much lower than in leaves, yet roots accumulate Met and SMM (Fig. 4). Both of these findings suggest that in reproductive stage plants, overaccumulated Met and SMM could be transported into flowers and roots, rather than being synthesized in situ. The most likely source tissues could be rosette and cauline leaves where CGS is overproduced, but where Met and SMM do not accumulate. Transport of Met/SMM during flowering may be a general feature of Arabidopsis, because the simultaneous decrease in soluble Met in rosette leaves and increase in flowers has also been observed in the mto1 and mto2 Arabidopsis mutants (Inaba et al., 1994; Bartlem et al., 2000).

The notion that Met is redistributed in plants has recently been raised by the finding of Bourgis et al. (1999) that SMM is a major amino acid constituent in the phloem sap of a wide range of angiosperms. SMM and Met are interconverted through the action of SAM-dependent Met S-methyltransferase (EC 2.1.1.12) and SMM:homocysteine S-methyltransferase (EC 2.1.1.10). Together these enzymes form the SMM cycle. If localized within the same cell the cycle would be futile. However, spatial separation of these enzymes such that SMM synthesis predominates in leaves and SMM→Met reconversion occurs in sink tissues, provides a mechanism for redistribution of Met (Hanson et al., 2000).

Analysis of various organs of transgenic Arabidopsis revealed that CGS expression varies widely in different tissues (Fig. 5) even though expression is under control of the potent and constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter. Although this promoter is not equally active in all cells (Holtorf et al., 1995), tissue-specific differences in activity cannot account for the inability to overexpress CGS in the stem, flowers, and roots of the transgenic plants. Thus, the evidence points toward a post-transcriptional mechanism for regulation of CGS expression in Arabidopsis. Paradoxically, it is the flowers and roots of flowering-stage plants that accumulate Met and SMM (Fig. 4). A Met-dependent autogenous control mechanism has been identified for Arabidopsis CGS (Chiba et al., 1999) that centers on a small conserved region of amino acid residues encoded by exon 1 of the CGS gene termed the MTO1 domain. In response to elevated Met (or one of its metabolites, possibly SAM, as will be described below), the MTO1 domain mediates the destabilization of CGS mRNA. This model could explain why the level of CGS is inversely correlated with soluble Met/SMM level in flowers and roots of flowering stage CGS transgenic plants. Perhaps, autogenous control is avoided in rosette leaves by rapid export of Met or SMM, whereas in sink tissues where Met and SMM accumulate autogenous control represses CGS expression. The post-translational control hypothesis does not explain, however, why CGS level is not repressed in young Arabidopsis leaves and roots even though Met and SMM are overaccumulated. Autogenous control of CGS has been demonstrated in seedling tissues (Inaba et a., 1994; Chiba et al., 1999). Perhaps, the higher level of CGS mRNA derived from the transcriptionally deregulated transgene overcomes the autogenous control mechanism. A factor that complicates interpretation of the results of CGS expression in transgenic plants is the fact that CGS becomes silenced in a high proportion of transgenic lines. Thus, it is possible that low-level expression of CGS in certain organs may be the result of cosuppression rather than autogenous regulation. However, this explanation cannot be generally true. Multiple independent samples were measured for each transgenic line, and for some lines the frequency of CGS silencing is low (<25% of the siblings), yet all showed a CGS expression pattern similar to the other lines. Moreover, care was taken to harvest samples only from plants with normal morphology in which, presumably, CGS silencing had not occurred.

The morphologies of CGS- and SAMS-silenced plants are remarkably similar, suggesting that the growth abnormalities are due in part to a reduced ability to produce SAM. Similar morphological aberrations are produced in Arabidopsis by inhibition of CGS expression through antisense RNA (Kim and Leustek, 2000). Both Met and SAM play central roles in plant metabolism. Thus, the question of which developmental processes are disrupted by the loss of CGS and SAM is complex. Indeed, it is more likely that many developmental processes are affected. For example, SAM is the precursor of ethylene and certain polyamines, and it serves as the methyl group donor in DNA methylation reactions. Ethylene and polyamines are known to play prominent roles in growth, flowering, and fruit development, so disruption of these processes by CGS and SAMS cosuppression is expected. Of potential significance is the phenotype of the Arabidopsis acl5 mutant carrying a mutation in the spermine synthase gene, which shows growth stunting and produces siliques with a bumpy surface (Hanzawa et al., 1997; Hanzawa et al., 2000), morphologies reminiscent of CGS- and SAMS-silenced plants. Inhibition of DNA methylation produces defects in apical dominance and flowering (Finnegan et al., 1996; Ronemus et al., 1996), also characteristic of CGS- and SAMS-silenced plants. Finally, several groups have reported that CGS expression is increased in developing fruits (Nam et al., 1999; Hadfield et al., 2000; Marty et al., 2000), and SAMS is highly expressed in developing pea seeds (Gomez-Gomez and Carrasco, 1998), further indicating their likely importance in fruit development.

An interesting property of plants showing CGS or SAMS cosuppression is the large scale, global increase in amino acids. Amino acids also accumulate in Arabidopsis where CGS level is reduced by expression of antisense RNA (Kim and Leustek, 2000). The only major difference between the lines is that SAMS-silenced plants accumulate Met and SMM, whereas CGS-silenced plants do not. There likely are multiple reasons for the increase in amino acids. The first possibility is that a block in translation causes free amino acids to accumulate. The silencing of CGS results in a limitation of Met (Fig. 3C), which probably causes translation to stall, slowing the rate of amino acid incorporation into proteins. Similar global increases in amino acids occur when a variety of amino acid biosynthetic enzymes are blocked with inhibitors or through antisense RNA techniques (Guyer et al., 1995; Höfgen et al., 1995; Kim and Leustek, 2000). SAMS silencing could also cause translation to stall. SAM is the precursor of the polyamines spermine and spermidine, which play vital roles at many different stages of translation (Yoshida et al., 2001). A second possibility is that CGS or SAMS silencing causes the rate of amino acid synthesis to increase. Guyer et al. (1995) found that the expression of certain amino acid biosynthesis enzymes is increased in Arabidopsis when starved for a single amino acid. They proposed that Arabidopsis might contain a general amino acid control system analogous to the one regulated by the GCN4-transcription factor in yeast. Whether the loss of CGS or SAMS causes the rate of amino acid synthesis to increase has not yet been studied. A third possibility is that amino acids accumulate in response to growth inhibition or stress, which could negatively affect translation, amino acid transport, amino acid degradation, or the synthesis of amino acids necessary for secondary product formation (Zhao et al., 1998).

SAMS-silenced plants accumulate 250-fold more Met than wild type. This level is much higher than the 3- to 5-fold accumulation of other amino acids, indicating that Met-specific processes have been activated in the SAMS-silenced plants. There are several possible explanations for the increase in Met. The loss of SAMS would be expected to eliminate a major route for Met metabolism. Also, the rate of Met synthesis would be expected to increase for the following reasons: (a) TS is allosterically activated by SAM (Curien et al., 1998), thus TS activity is probably reduced in SAMS-silenced plants because of the likely reduction in SAM level; (b) CGS expression is increased by 3-fold (Fig. 7); and (c) the level of OPH is greater in SAMS-silenced plants (not shown). All of these effects would allow increased ability of CGS to direct OPH toward Met.

The pleiotropic effect of SAMS silencing on CGS expression is particularly intriguing because CGS level is increased despite the accumulation of extremely high Met levels. Previous results showed that application of Met to living plants causes a decline in CGS level (Thompson et al., 1982; Chiba et al., 1999). However, in these studies it was not clear whether CGS repression was caused by Met or one of its metabolites, e.g. SAM. The present result suggests that SAM, rather than Met, is probably the negative regulator of CGS expression. If so, it is tempting to speculate that SAM is the factor that mediates autogenous control of CGS expression mediated through the MTO1 region. An unfortunate deficiency of the present manuscript is that we have been unable to carry out reliable measurements of SAM. The inadequacy of presently existing methodologies for measurement of SAM from plant samples has been noted (Hanson and Roje, 2001). Nonetheless, to test the hypothesis that SAM is the effector of CGS expression in vivo, it will be essential to develop a sensitive and reliable method for use with Arabidopsis.

In this study, no attempt was made to discern the mechanism for CGS or SAMS silencing. However, both silencing events share the properties that they occur sporadically during development, are unstable, and are not meiotically stable. The meiotic instability is a hallmark of post-transcriptional gene silencing, a process that is influenced by the state of DNA methylation (Morel et al., 2000). In this regard it is interesting to note that changes in expression of both CGS and SAMS could potentially influence the state of DNA methylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General Methods, Strains, Growth Media, and Growth Conditions

Molecular biology methods were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (1989). Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Inc., Hercules, CA). Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain pGV2260 was used for transformation of Arabidopsis ecotype Colombia. A. tumefaciens was grown on yeast extract and peptone medium (10 g L−1 peptone, 10 g L−1 yeast extract, and 10 g L−1 NaCl). Arabidopsis plants were grown in vitro on agar medium, in potting mix, or in hydroponic medium. Growth on agar medium was under axenic conditions on 0.5× Murashige and Skoog nutrients (Life Technologies, Gaithersberg, MD) solidified with 8 g L−1 agar. Whenever supplements were added they are so indicated in the text. When grown on soil-less potting mix the seeds of segregating transgenic lines were transplanted after an initial selection on Kan-containing agar medium, or in the case of homozygous plants, were germinated directly on potting mix. The plants were fertilized at each watering with one-quarter-strength Peters (20:20:20, N:P:K) fertilizer (Grace-Sierra Co., Milpitas, CA) prepared in distilled water. Plants were grown hydroponically as described by Lee and Leustek (1998). All plants were incubated in growth chambers at 24°C with a diurnal cycle of 14-h light/10-h darkness. The light intensity was controlled at 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Some experiments focused on transgenic Arabidopsis (Columbia) transformed with a construct for SAMS overexpression (Boerjan, 1993; Boerjan et al., 1994; de Carvalho et al., 1994).

Preparation of the CGS Transformation Construct and Transformation of Arabidopsis

A construct was prepared for stable overexpression of CGS in transgenic plants. The full-length CGS cDNA (Kim and Leustek, 1996; GenBank accession no. U43709) was cloned as an approximately 2-kb KpnI-XbaI fragment into the same sites of pFF19 (Timmermans et al., 1990). Then an approximately 3-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment including the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, CGS cDNA in the sense orientation, and the termination sequence was subcloned into the same sites of the binary vector pBI101. This construct was used to transform A. tumefaciens. Transformation of Arabidopsis was performed by vacuum infiltration (Bechtold and Pelletier, 1998). Transgenic T1 plants were selected by germination of seeds from the vacuum infiltrated plants on Murashige and Skoog medium with 50 μg mL−1 Kan.

Analysis of Transgenic Arabidopsis

The Kan-resistant plants were transferred to soil and their morphology observed throughout development. Analyses were conducted on plants taken up to the fourth transgenic generation. Plant tissues were analyzed by immunoblotting, CGS enzyme activity, PCR, and amino acid analysis. In addition to the analytical procedures, transgenic plants were tested for resistance to ethionine and PAG.

Ethionine and PAG resistance was studied by germinating seeds on Murashige and Skoog-agar medium supplemented with various concentrations of ethionine up to 50 μm or PAG up to 60 μm. Seedling growth was observed over time.

The transgene construct was detected in Kan-resistant plants by PCR (Lassner et al., 1989) using a 35S promoter-specific primer and a CGS-specific primer. The primer sequences were, 5′-TATCTCCACTGACGTAAGGGATGA- 3′ and 5′-GGTCTAGAGAGAGAAGAGAACGAGAG-3′.

Immunoblotting was performed as described by Wang et al. (1993). The antibodies used in this study included one raised against Arabidopsis CGS (Kim and Leustek, 2000), an antibody against Arabidopsis SAT (Murillo et al., 1995), and an antibody raised against Catharanthus roseus SAMS (Schröder et al., 1997). Antibody complexes were detected on Kodak X-OMAT film (Rochester, NY) using the Renaissance Kit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston). The CGS antibody has previously been shown to accurately reflect the activity of CGS in transgenic plant tissues (Kim and Leustek, 2000). Unless stated otherwise, 5 μg of protein was analyzed. The CGS antiserum was used at 1:10,000 dilution, the SAT antiserum at 1:2,000 dilution, and the SAMS antiserum at 1:5,000 dilution.

CGS activity was measured in soluble protein extracts prepared from leaves in 20 mm MOPS-NaOH, pH 7.4. The assay was carried out with either OPH or O-succinylhomoserine either of which are used by CGS (Thompson et al., 1982; Ravanel et al., 1995). Unless noted otherwise OPH was used. The reaction mixture (100 μL) contained 20 mm MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.5), 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm pyridoxal phosphate, 1 mm l-Cys, 0.44 mm OPH, and 50 μg of total protein. Reactions lacking OPH were incubated for 1 h, and then OPH was added and the incubation continued at 30°C; samples were taken for analysis at 0, 10, 20, and 30 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of 100 μL of 40 mm HCl. After centrifugation, 10 μL of the reaction was derivatized with AQC reagent (Waters, Inc., Milford, MA), and cystathionine was measured by HPLC as described below. When O-succinylhomoserine was used as a substrate the assay was performed as described by Ravanel et al. (1995) and modified by Kim and Leustek (2000). All enzyme activities are the mean of three independent measurements ± sd.

For amino acid analysis, plants or plant tissues were weighed in microcentrifuge tubes, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. All plant material was harvested 8 h into the light period. Frozen plant material was ground with a pestle to a fine powder in the microcentrifuge tube and was further homogenized at 5°C in 20 mm HCl using a ratio of 10 μL of HCl for each milligram of tissue. Norleucine was added as an internal standard. Tissue extracts were centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000g, 4°C. The supernatant was recovered and amino acids derivatized with 6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate (AQC; Cohen and van Wandelen, 1997) using an AccQ-Fluor Reagent Kit (Waters, Inc.). Ten microliters of the supernatant was added to 70 μL of borate buffer. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 20 μL of AQC reagent followed immediately by mixing and then incubation for 1 min at room temperature. Five microliters was injected onto the column. HPLC was performed using a Beckman model 126 solvent delivery system, autosampler, and 32 Karat System Gold data collection and analysis software (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Separations were performed on a 3.9- × 150-mm Waters Nova-Pak C18 column equipped with a Nova-Pak C18 Guard-Pak insert. Eluted amino acid-derivatives were detected using a Hitachi model F1080 Fluorescence Detector (Danbury, CT) with an excitation wavelength of 250 nm and an emission wavelength of 395 nm. Eluent A containing sodium acetate and triethylamine at pH 5.05 was purchased as a premix from Waters; eluent B was acetonitrile:water (60:40). The elution protocol was 0 to 0.5 min, 100% A; 0.5 to 5.0 min, linear gradient to 5% B; 5 to 35 min, linear gradient to 7.5% B; 35 to 41 min, linear gradient to 10% B; 41 to 44 min, 10% B; 44 to 54 min, linear gradient to 20% B; 54 to 61 min, 20% B; 61 to 71 min, linear gradient to 30% B; 71 to 86 min, linear gradient to 100% B. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. Standard solutions of each amino acid were analyzed at several concentrations to calculate a detector response factor. All amino acid standards were commercially obtained, except for OPH, which was synthesized and purified as described by Lee and Leustek (1999). SMM was also measured by the AQC method.

RNA was purified from 100 mg fresh weight of tissue by grinding in 1 mL of buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 2 mm aurin tricarboxylic acid, 14 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, and 2% (w/v) SDS. The supernatant was recovered after centrifugation and RNA precipitated by addition of 0.4 mL of 8 m LiCl and incubation overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation, the pellet was dissolved in 0.4 mL of 2 mm aurin tricarboxylic acid and extracted with an equal volume of pH neutralized phenol. Finally, the RNA was precipitated with 50 mm sodium acetate and ethanol. RNA was electrophoresed on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel containing formaldehyde (Sambrook et al., 1989), blotted onto HyBond-N+ membrane (Amersham, Inc., Buckinghamshire, UK) and hybridized with a CGS cDNA probe. The highest stringency wash of the membrane was 0.1% (w/v) SSC, 0.1% (w/v) SDS at 65°C for 2 h. The blot was exposed to Kodak X-Omat film. The probe was prepared using a random primer labeling kit (Gibco-BRL, Inc., Cleveland) and [α-32P]dCTP (111 TBq mmol−1, New England Nuclear, Inc., Boston).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Dr. Satoshi Naito, who kindly provided seed for Arabidopsis mto1, and to Dr. Joachim Schröder, who kindly provided antibodies against SAMS.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. MCB–9728661 to T.L. and MCB–0094062 to M.N.M.) and Pioneer Hi-Bred, Inc.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.101801.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bechtold N, Pelletier G. In planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants by vacuum infiltration. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;82:259–266. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-391-0:259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlem D, Lambein I, Okamoto T, Itaya A, Uda Y, Kijima F, Tamaki Y, Nambara E, Naito S. Mutation in the threonine synthase gene results in an over-accumulation of soluble methionine in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:101–110. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerjan W. Moleculaire technieken voor de studie van genexpressie in planten. PhD thesis. Belgium: Universiteit Gent; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Boerjan W, Bauw G, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. Distinct phenotypes generated by overexpression and suppression of S-adenosyl-l-methionine synthetase reveal developmental patterns of gene silencing in tobacco. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1401–1414. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.10.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgis F, Roje S, Nuccio ML, Fisher DB, Tarczynski MC, Li C, Herschbach C, Rennenberg H, Pimenta MJ, Shen TL. S-methylmethionine plays a major role in phloem sulfur transport and is synthesized by a novel type of methyltransferase. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1485–1498. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.8.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Ishikawa M, Kijima F, Tyson RH, Kim J, Yamamoto A, Nambara E, Leustek T, Wallsgrove RM, Naito S. Evidence for autoregulation of cystathionine gamma-synthase mRNA stability in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;286:1371–1374. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SA, van Wandelen C. Amino acid analysis of unusual and complex samples based on 6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate derivitization. In: Crabb JW, editor. Techniques in Protein Chemistry VIII. New York: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Curien G, Job D, Douce R, Dumas R. Allosteric activation of Arabidopsis threonine synthase by S-adenosylmethionine. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13212–13221. doi: 10.1021/bi980068f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datko AH, Mudd SH. Methionine biosynthesis in Lemna: inhibitor studies. Plant Physiol. 1982;69:1070–1076. doi: 10.1104/pp.69.5.1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho F, Boerjan W, Ingelbrecht I, Depicker A, Inzé D, Van Montagu M. Post-transcriptional gene silencing in transgenic plants. In: Coruzzi G, Puigdomenech P, editors. Plant Molecular Biology: Molecular Genetic Analysis of Plant Development and Metabolism, NATO-ASI Series H. Vol. 81. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1994. pp. 437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan EJ, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES. Reduced DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana results in abnormal plant development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8449–8454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gakiére B, Ravanel S, Droux M, Douce R, Job D. Mechanisms to account for maintenance of the soluble methionine pool in transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing antisense cystathionine gamma-synthase cDNA. CR Acad Sci III. 2000;323:841–851. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(00)01242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli J, Mudd SH, Datko AH. Sulfur amino acids in plants. In: Miflin BJ, editor. The Biochemistry of Plants: A Comprehensive Treatise. 5, Amino Acids and Derivatives. New York: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 454–500. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gomez L, Carrasco P. Differential expression of the S-adenosyl-l-methionine synthase genes during pea development. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:397–405. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.2.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer D, Patton D, Ward E. Evidence for cross-pathway regulation of metabolic gene expression in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4997–5000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield KA, Dang T, Guis M, Pech JC, Bouzayen M, Bennett AB. Characterization of ripening-regulated cDNAs and their expression in ethylene-suppressed charentais melon fruit. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:977–993. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.3.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson AD, Gage DA, Shacher-Hill Y. Plant one-carbon metabolism and its engineering. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:206–213. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson AD, Roje S. One carbon metabolism in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2001;52:119–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa Y, Takahashi T, Komeda Y. ACL5: an Arabidopsis gene required for internodal elongation after flowering. Plant J. 1997;12:863–874. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.12040863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa Y, Takahashi T, Michael AJ, Burtin D, Long D, Pineiro M, Coupland G, Komeda Y. ACAULIS5, an Arabidopsis gene required for stem elongation, encodes a spermine synthase. EMBO J. 2000;19:4248–4256. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höfgen R, Laber B, Schüttke I, Klonus A-K, Steber W, Pohlenz H-D. Repression of acetolactate synthase activity through antisense inhibition: molecular and biochemical analysis of transgenic potato (Solanum tuberosum L. cv Désirée) plants. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:469–477. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtorf S, Apel K, Bohlmann H. Comparison of different constitutive and inducible promoters for the overexpression of transgenes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;29:637–646. doi: 10.1007/BF00041155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K, Fujiwara T, Hayashi H, Chino M, Komeda Y, Naito S. Isolation of an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant, mto1, that overaccumulates soluble methionine. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:881–887. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M, Jankowski D, Marcotte P, Tanaka H, Esaki N, Soda K, Walsh C. Suicide inactivation of bacterial cystathionine gamma-synthase and methionine gamma-lyase during processing of l-propargylglycine. Biochemistry. 1979;18:4690–4701. doi: 10.1021/bi00588a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Leustek T. Cloning and analysis of the gene for cystathionine gamma-synthase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:1117–1124. doi: 10.1007/BF00041395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Leustek T. Repression of cystathionine γ-synthase in Arabidopsis thaliana produces partial methionine auxotrophy and developmental abnormalities. Plant Sci. 2000;151:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lassner MW, Peterson P, Yoder JI. Simultaneous amplification of multiple DNA fragments by polymerase chain reaction in the analysis of transgenic plants and their progeny. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1989;7:116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lee M-S, Leustek T. Identification of the gene encoding homoserine kinase from Arabidopsis thaliana and characterization of the recombinant enzyme derived from the gene. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;372:135–142. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Leustek T. APS kinase from Arabidopsis thaliana, genomic organization, expression, and kinetic analysis of the recombinant enzyme. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1998;247:171–175. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty I, Douat C, Tichit L, Kim J, Leustek T, Abagnac G. The cystathionine-γ-synthase gene involved in methionine biosynthesis is highly expressed and auxin-repressed during wild strawberry (Fragaria vesca L.) fruit ripening. Theor Appl Genet. 2000;100:1129–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Morel J, Mourrain P, Beclin C, Vaucheret H. DNA methylation and chromatin structure affect transcriptional and post-transcriptional transgene silencing in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1591–1594. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00862-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillo M, Foglia R, Diller A, Lee S, Leustek T. Serine acetyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana can functionally complement the cysteine requirement of a cysE mutant strain of Escherichia coli. Cell Mol Biol Res. 1995;41:425–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam YW, Tichit L, Leperlier M, Cuerq B, Marty I, Lelievre JM. Isolation and characterization of mRNAs differentially expressed during ripening of wild strawberry (Fragaria vesca L.) fruits. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;39:629–636. doi: 10.1023/a:1006179928312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleman J, Boerjan W, Engler G, Seurinck J, Botterman J, Alliotte T, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. Strong cellular preference in the expression of a housekeeping gene of Arabidopsis thaliana encoding S-adenosylmethionine synthetase. Plant Cell. 1989;1:81–93. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanel S, Droux M, Douce R. Methionine biosynthesis in higher plants: I. Purification and characterization of cystathionine gamma-synthase from spinach chloroplasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;316:572–584. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronemus MJ, Galbiati M, Ticknor C, Chen J, Dellaporta SL. Demethylation-induced developmental pleiotropy in Arabidopsis. Science. 1996;273:654–657. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder G, Eichel J, Breinig S, Schroder J. Three differentially expressed S-adenosylmethionine synthetases from Catharanthus roseus: molecular and functional characterization. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;33:211–222. doi: 10.1023/a:1005711720930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson GA, Datko AH, Mudd SH, Giovanelli J. Methionine biosynthesis in Lemna: studies on the regulation of cystathionine γ-synthase, O-phosphohomoserine sulfhydrase, and O-acetylserine sulfhydrase. Plant Physiol. 1982;69:1077–1083. doi: 10.1104/pp.69.5.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans MC, Maliga P, Vieira J, Messing J. The pFF plasmids: cassettes utilising CaMV sequences for expression of foreign genes in plants. J Biotechnol. 1990;14:333–344. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(90)90117-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Goffreda M, Leustek T. Characteristics of an Hsp70 homolog localized in higher plant chloroplasts that is similar to DnaK, the Hsp70 of prokaryotes. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:843–850. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Kashiwagi K, Kawai G, Ishihama A, Igarashi K. Polyamine enhancement of the synthesis of adenylate cyclase at the translational level and the consequential stimulation of the synthesis of the RNA polymerase sigma 28 subunit. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16289–16295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Williams CC, Last RL. Induction of Arabidopsis tryptophan pathway enzymes and camalexin by amino acid starvation, oxidative stress, and an abiotic elicitor. Plant Cell. 1998;10:359–370. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]