Abstract

Since Vibrio cholerae O139 first appeared in 1992, both O1 El Tor and O139 have been recognized as the epidemic serogroups, although their geographic distribution, endemicity, and reservoir are not fully understood. To address this lack of information, a study of the epidemiology and ecology of V. cholerae O1 and O139 was carried out in two coastal areas, Bakerganj and Mathbaria, Bangladesh, where cholera occurs seasonally. The results of a biweekly clinical study (January 2004 to May 2005), employing culture methods, and of an ecological study (monthly in Bakerganj and biweekly in Mathbaria from March 2004 to May 2005), employing direct and enrichment culture, colony blot hybridization, and direct fluorescent-antibody methods, showed that cholera is endemic in both Bakerganj and Mathbaria and that V. cholerae O1, O139, and non-O1/non-O139 are autochthonous to the aquatic environment. Although V. cholerae O1 and O139 were isolated from both areas, most noteworthy was the isolation of V. cholerae O139 in March, July, and September 2004 in Mathbaria, where seasonal cholera was clinically linked only to V. cholerae O1. In Mathbaria, V. cholerae O139 emerged as the sole cause of a significant outbreak of cholera in March 2005. V. cholerae O1 reemerged clinically in April 2005 and established dominance over V. cholerae O139, continuing to cause cholera in Mathbaria. In conclusion, the epidemic potential and coastal aquatic reservoir for V. cholerae O139 have been demonstrated. Based on the results of this study, the coastal ecosystem of the Bay of Bengal is concluded to be a significant reservoir for the epidemic serogroups of V. cholerae.

Cholera is a devastating disease, the epidemics of which, until 1992, were caused by Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 biotype classical or El Tor. The classical biotype is believed to have caused the first six pandemics, which occurred in the Indian subcontinent and subsequently in other areas of the world between 1817 and 1923 (9, 27). V. cholerae O1 biotype El Tor was first reported in 1905 (30). However, it was not until the early 1960s that V. cholerae biotype El Tor displaced the sixth-pandemic V. cholerae O1 classical biotype (11, 32). The emergence in 1992 of a V. cholerae non-O1 serovar, designated V. cholerae synonym O139 Bengal, in Bangladesh (2, 4) and India (28) and its subsequent appearance in Southeast Asia, displacing V. cholerae O1 El Tor, was considered a significant point in the history of cholera (33). V. cholerae O1 El Tor reemerged in 1994 to 1995, but V. cholerae O139 continues to coexist with V. cholerae O1 as indicated by its temporal quiescence and subsequent reemergence in 1997, 1999, and 2002 (11, 15). Of all of these outbreaks, the resurgence of V. cholerae O139 in a major outbreak, resulting in an estimated 30,000 cases in Dhaka, Bangladesh, caused more cases than the number attributed to V. cholerae O1 El Tor within a very short time (11, 30). Since then, V. cholerae serogroup O139 has continued to cause a small number of cases of cholera in the subcentral parts of Bangladesh and southern Bangladesh (34). Despite its significance as a causal agent of cholera, little is known about the geographic distribution of V. cholerae O139 in the coastal areas of the Bay of Bengal.

Despite being autochthonous to the aquatic environment (6, 7), toxigenic strains of V. cholerae O1 are only infrequently isolated from surface waters by culture methods (7, 21) and are rarely isolated during interepidemic periods (18). It was when fluorescent-antibody (FA) and molecular-based detection methods were used that the presence of V. cholerae O1 in the environment was unequivocally demonstrated (3, 18) and its viable but not culturable state was discovered (5, 7, 18, 29). V. cholerae O139 has been shown to behave similarly to V. cholerae O1, since detection and isolation of V. cholerae O139 from water samples were negative by culture methods between epidemics (19, 21).

The correlation of sea surface temperature and sea surface height in the Bay of Bengal with the occurrence of cholera in Bangladesh has been established (8). Field studies in Bakerganj, which is located 70 km north of the Bay of Bengal coast, showed correlation of selected environmental parameters with the ecology and epidemiology of V. cholerae and cholera, respectively (19). In 1992, V. cholerae serogroup O139 was first isolated in Bangladesh in the vicinity of the Bay of Bengal. With the resurgence of V. cholerae O139 in 2002, the number of cholera cases caused by this serogroup surpassed the number caused by V. cholerae O1 in Bangladesh. This phenomenon is believed to have been the result of rapid genetic changes in V. cholerae O139, with at least seven different ribotypes detected (10, 11, 13). The reservoir for V. cholerae O139 is not known (11). Therefore, combined epidemiological and ecological surveillance was undertaken in two sites where cholera is endemic, Bakerganj and Mathbaria, which are located near the Bay of Bengal and have not been studied previously. The seasonality of cholera in the coastal ecosystem of Mathbaria and the subcentral Bakerganj is such that seasonal outbreaks are caused alternatively by V. cholerae O1 El Tor and O139. Results of direct culture, coupled with colony blot hybridization (CBH), selective culture, and direct FA assay (DFA), obtained in the study reported here demonstrate that V. cholerae O1 El Tor and O139 are present in the aquatic environment of both Bakerganj and Mathbaria, Bangladesh, throughout the year.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of study areas. (i) Bakerganj.

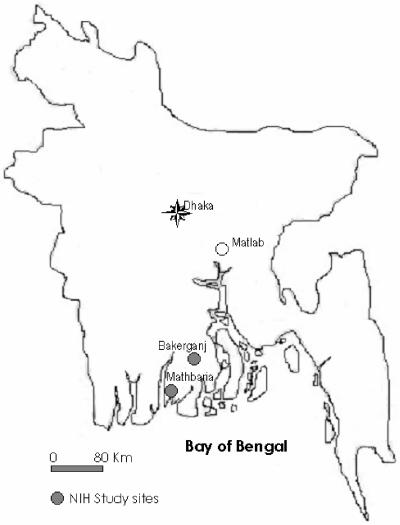

Bakerganj, an administrative unit comprising a group of villages, is located in the southern district of Barisal, about 70 km north of the coast of the Bay of Bengal and approximately 300 km southwest of Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh (Fig. 1). Epidemiological and ecological surveillance (31) showed significant correlation between selected environmental parameters and the ecology and epidemiology of V. cholerae in Bakerganj (19). Stool samples were collected biweekly from patients attending the Thana (local government) Health Complex (THC) of Bakerganj, and water and plankton samples were also collected from four sites (a river, a pond, and two lakes). In the present study, which was part of the ongoing epidemiological and ecological surveillance in Bakerganj, samples were collected biweekly from the patients attending the THC and monthly from eight environmental sites (one river, five ponds, and two lakes). The THC is a government-run, community-level, rural health care facility that contains hospital beds. The sampling sites included the major river, Tulatali, which flows through Bakerganj, and man-made ponds and lakes that are located in the villages and heavily used by nearby villagers for drinking and other domestic purposes.

FIG. 1.

Map of Bangladesh showing areas where the NIH epidemiological and ecological surveillance was conducted. Bakerganj and Mathbaria are the two southern foci of endemic cholera. The central foci of endemic cholera, Matlab and Dhaka (the capital of Bangladesh), are also shown.

(ii) Mathbaria.

Mathbaria is located adjacent to the Bay of Bengal, approximately 400 km southwest of Dhaka (Fig. 1). Mathbaria is also an administrative unit under the district of Pirojpur, with a police station and a THC. This area has not been studied previously. The THC in Mathbaria is government run at the community level and is a rural health care facility containing hospital beds. In this study, samples from Mathbaria were collected biweekly from patients attending the THC of Mathbaria and from six man-made ponds (one of which is linked to a river) that are heavily used for drinking and other domestic purposes. The major river, Baleshwar, flows along the western boundary of Mathbaria, on the other side of which is located a tropical mangrove forest of the Sundarbans, the temporary island system of that part of the Bay of Bengal.

Collection and analysis of clinical specimens.

Biweekly clinical surveillance was carried out routinely in Bakerganj and Mathbaria between January 2004 and May 2005, for a period of 17 months. Rectal swabs were obtained every 2 weeks from patients admitted to the THCs of Bakerganj and Mathbaria. The rectal swabs, from suspected cholera patients with watery stool, were collected for three consecutive days and after each collection were immediately placed into Cary-Blair medium (35, 36) and transported to the central laboratory of the International Center for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B), in Dhaka. In the laboratory, the rectal swabs were placed in alkaline peptone water (APW) (Bacto Peptone, 10 g/liter; sodium chloride, 10 g/liter; pH 8.8) and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. The rectal swabs, as well as the 4-h broth enrichments, were inoculated by streaking on taurocholate-tellurite-gelatin agar (TTGA) (Trypticase, 10 g/liter; sodium chloride, 10 g/liter; sodium taurocholate, 5 g/liter; sodium carbonate, 1 g/liter; gelatin, 30 g/liter; agar, 15 g/liter; pH 8.5) (after autoclaving, the agar was cooled to 50°C and 5 ml of 0.1% potassium tellurite solution added and mixed well, after which the agar was poured into plates). Suspected colonies resembling V. cholerae were subjected to slide agglutination using polyvalent anti-O1 and anti-O139 sera.

Collection of environmental samples and processing.

Water and plankton samples were collected monthly between March 2004 and May 2005 from seven ponds and one river in Bakerganj and biweekly from six ponds in Mathbaria (Fig. 1). All samples were collected with aseptic technique using sterile dark Nalgene bottles (Nalgene Nunc International, St. Louis, Mo.), placed in an insulated plastic box, and transported overnight at ambient air temperature ranging from 20 to 35°C from the site of collection to the Dhaka laboratory of ICDDR, B. All samples were processed the following morning, with approximately 20 h elapsing between sample collection in the field and processing in the laboratory.

For sample collection, 100 liters of water was filtered successively through 64-μm and 20-μm mesh nylon nets (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA) (placing the 64-μm net sequentially in front of the 20-μm nylon net, with each having a collection bucket at the base), and 50 ml of the concentrates was collected initially as a crude measure of zooplankton and phytoplankton, respectively. However, it was observed that the small-size fraction contained nauplii of zooplankton in large numbers. Also, during the process of filtration, 500 ml of filtrates from the 20-μm mesh net was collected as the representative water to be analyzed for planktonic (unattached, free-living) bacteria. Both the 64-μm and 20-μm plankton samples were further concentrated in the laboratory by using respective plankton nets (specially devised, netted plastic beakers) to a final volume of 5 ml each. For bacteriological analysis, the plankton samples were crushed using a glass homogenizer (Elberbach Corp., Ann. Arbor, Mich.) to release the attached bacteria. The homogenates were used for DFA, direct plating, and enrichment for V. cholerae. Water samples were concentrated by being filtered through a 0.22-μm bacteriological membrane filter (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA), and the retained content on the membrane filter was washed into phosphate-buffered saline (pH 8.0) for the purpose stated above. DFA was also carried out on whole plankton samples when homogenates tested positive for V. cholerae O1 and/or O139.

Enrichment and plating.

Samples were enriched in APW (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C for 6 to 8 h before plating, as described previously (18, 21). About 5 μl of enriched APW broth was streaked, using an inoculating loop, onto both thiosulfate-citrate-bile-salts-sucrose (TCBS) and TTGA and incubated at 37°C for 18 to 24 h. Colonies with the characteristic appearance of V. cholerae were confirmed by standard biochemical (35, 36) and serological tests (and, in the case of the latter, by testing with polyvalent and monoclonal antibodies specific for V. cholerae O1 or O139) and, finally, by molecular methods (26).

CBH.

Digoxigenin (DIG) labeling of the ctxA probe and detection were performed following the manufacturer's protocol supplied with the DIG DNA labeling and detection kit obtained from Boehringer Mannheim Corp. Briefly, neat or appropriately diluted samples were spread plated directly onto Luria-Bertani agar (LA) plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. Colonies (between 100 and 300) from each culture plate were lifted onto a nylon membrane (Magna; Osmonics Inc.) by impression. The membranes with adherent colonies were placed, keeping the colony side up, onto no. 3 Whatman filter paper presoaked with lysis buffer (0.5 M NaOH and 1.5 M NaCl), followed by placing twice onto no. 3 Whatman filters presoaked with neutralizing solution (0.5 M Tris [pH 7.2] and 1.5 M NaCl). Finally, the filters were rinsed twice in 1× SSC buffer (0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). The filters were dried (28) and treated with 100 ml of proteinase K solution (40 μg/ml in 1× SSC) for 30 min at 42°C with gentle shaking. The filters were rinsed three times in 1× SSC in a shaking water bath for 10 min at room temperature and were then air dried.

Oligonucleotides used as primers for PCR amplification of 302 bp of ctxA were 5′-CTCAGACGGGATTTGTTAGGCACG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCTATCTCTGTAGCCCCTATTACG-3′ (reverse) (16). The amplified target DNA was purified, and DIG labeling was performed following the manufacturer's protocol supplied with the DIG DNA labeling kit. After prehybridization, hybridization, and stringency washing, blots were developed following the immunochemical detection protocol supplied by the manufacturer.

DFA.

DFA counts were done as described elsewhere (3). Briefly, samples were preincubated overnight in the dark with 0.025% yeast extract (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and 0.002% nalidixic acid (Sigma). The samples were then centrifuged and the pellet stained, using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated V. cholerae O1- or O139-specific antiserum obtained from New Horizon Diagnostic Corp. (Columbia, MD). Stained samples were counted under UV light, using an epifluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51, Japan) connected to a digital camera (Olympus DP20).

RESULTS

Surveillance in Bakerganj Hospital.

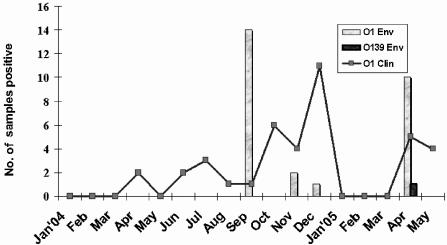

Of the total of 182 rectal swabs collected biweekly for three consecutive days each week between January 2004 and May 2005, 39 (21%) were positive by culture for V. cholerae serovar O1; however, none of the samples was positive for V. cholerae O139 (Table 1). The first cholera cases of the year in Bakerganj were recorded in April 2004 and again in June, with a small number of cases occurring until October 2004, when a huge seasonal outbreak, deemed the fall peak of cholera, began in Bakerganj. The fall peak of cholera, which was caused exclusively by V. cholerae O1, continued until December 2004 (Fig. 2). The biweekly surveillance continued in Bakerganj, and the first outbreak of 2005 was recorded in April 2005 and continued until May 2005 (Fig. 2). Of the 149 diarrheal stool samples collected during these seasonal outbreaks in Bakerganj, 27% were confirmed as being from persons with cholera, and all of the cholera cases in Bakerganj were shown to be caused by V. cholerae O1 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Isolation of V. cholerae O1 and O139 from clinical and environmental samples collected at Bakerganj and Mathbaria between January 2004 and May 2005a

| Yr and mo | Clinical surveillanceb

|

Environmental surveillancec

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakerganj

|

Mathbaria

|

Bakerganj

|

Mathbaria

|

|||||||||

| Total no. of samples | Total no. positive

|

Total no. of samples | Total no. positive

|

Total no. of samples | Total no. positive

|

Total no. of samples | Total no. positive

|

|||||

| V. cholerae O1 | V. cholerae O139 | V. cholerae O1 | V. cholerae O139 | V. cholerae O1 | V. cholerae O139 | V. cholerae O1 | V. cholerae O139 | |||||

| 2004 | ||||||||||||

| Jan. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | NDd | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Feb. | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| March | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 2 |

| April | 10 | 2 | 0 | 24 | 13 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | ND |

| May | 7 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 11 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| June | 10 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| July | 10 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Aug. | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 51 | 0 | 0 |

| Sept. | 8 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 16 (4) | 0 | 36 | 0 | 4 (1) |

| Oct. | 18 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 0 |

| Nov. | 17 | 4 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 24 | 2 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 0 |

| Dec. | 27 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 1 | 0 | 36 | 12 | 0 |

| 2005 | ||||||||||||

| Jan. | 6 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 1 (1) | 0 | 54 | 0 | 0 |

| Feb. | 8 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 0 |

| March | 9 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 4 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 0 |

| April | 17 | 5 | 0 | 41 | 12 | 6 | 24 | 11 (2) | 1 (1) | 36 | 2 | 19 (3) |

| May | 19 | 4 | 0 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Total | 182 | 39 | 0 | 194 | 42 | 10 | 360 | 31 (7) | 1 (1) | 495 | 15 (1) | 26 (5) |

Clinical and environmental surveillance began in January and March 2004, respectively.

Clinical samples were collected every 15 days for three consecutive days.

Environmental samples were collected monthly in Bakerganj and biweekly in Mathbaria. Numbers in parentheses indicate strains isolated from LA plates, based on a positive CBH signal.

ND, not done.

FIG. 2.

Isolation of V. cholerae O1 and O139 Bengal by month from clinical (Clin) and environmental (Env) samples collected in Bakerganj, a subcentral, southern focus of endemic cholera in Bangladesh. Rectal swabs (n = 182) from suspected cholera patients, collected biweekly (January 2004 to May 2005) for three consecutive days at the Thana Health Complex, were maintained in Cary-Blair medium for microbiological analysis. Environmental samples (n = 360; 120 each of water and of two size fractions of plankton), collected monthly (March 2004 to May 2005) from eight water bodies, were transported to Dhaka for microbiological analysis. For isolation of V. cholerae, clinical samples were streaked directly and environmental samples were either plated directly on LA for CBH or subjected to selective enrichment before being plated on TCBS and TTGA. Suspected V. cholerae colonies were identified by standard biochemical (35, 36), serological, and molecular methods (26).

Surveillance in Mathbaria Hospital.

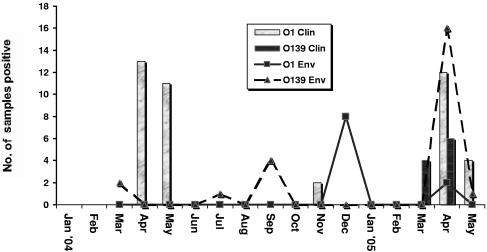

Of the 194 rectal swabs collected from patients with diarrhea between January 2004 and May 2005, 52 (27%) were concluded to be from persons with cholera, of which 42 cases (81%) were caused by V. cholerae serovar O1 and the remaining by V. cholerae O139 Bengal (Table 1). Three outbreaks of cholera were recorded in Mathbaria; two were in the spring and fall of 2004, respectively, and the third was in the spring of 2005 (Fig. 3). Again, of 108 samples collected during these seasonal outbreaks in Mathbaria, as many as 48% of the cases were confirmed to be cholera.

FIG. 3.

Isolation of V. cholerae O1 and O139 Bengal by month from clinical (Clin) and environmental (Env) samples collected in Mathbaria, a coastal focus of endemic cholera located adjacent to the Bay of Bengal. Rectal swabs (n = 194) from suspected cholera patients, collected biweekly (January 2004 to May 2005) for three consecutive days at the Thana Health Complex, were maintained in Cary-Blair medium for microbiological analysis. Environmental samples (n = 495; 165 each of water and of two size fractions of plankton), collected biweekly (March 2004 to May 2005) from six water bodies, were transported to Dhaka for microbiological analysis. For isolation of V. cholerae, clinical samples were streaked directly and environmental samples were either plated directly on LA for CBH or subjected to selective enrichment before plating on TCBS and TTGA. Suspected V. cholerae colonies were identified by standard biochemical (35, 36), serological, and molecular methods (26).

The first seasonal outbreak of 2004 in Mathbaria was caused by V. cholerae O1. It began in April 2004 and ended in May 2004 (Fig. 3). The second cholera outbreak in Mathbaria, also caused by V. cholerae O1, began in November 2004 and ended in the same month. In March 2005, an outbreak of cholera caused exclusively by V. cholerae O139 began in Mathbaria (Fig. 3). V. cholerae O1, the single cause of cholera in Mathbaria in the previous two outbreaks in 2004, was completely displaced by V. cholerae O139. Interestingly, the V. cholerae O139 outbreak, which continued for several weeks, until mid-April 2005, was overtaken by a fresh outbreak caused by V. cholerae O1 El Tor. As soon as the V. cholerae O1 El Tor reemerged in mid-April 2005, cholera caused by V. cholerae O139 declined, and by early May 2005, V. cholerae O1 El Tor remained the single cause of cholera in Mathbaria.

Environmental surveillance in Bakerganj.

Of the 360 environmental samples collected in Bakerganj (120 each of water and of two size fractions of plankton) between March 2004 and May 2005, over a period of 15 months, 32 (9%) yielded cholera vibrios, of which 31 (97%) were V. cholerae serovar O1 and 1 was serovar O139 (Table 1). Isolation of V. cholerae was accomplished by employing direct culture of samples on L agar, followed by CBH and APW enrichment, followed by selective culture. Of the 32 cholera vibrios, 24 (75%) of the V. cholerae O1 strains were isolated by enrichment and selective culture and 7 (22%) of the V. cholerae O1 strains and 1 (3%) of the V. cholerae O139 strains were isolated by direct culture, based on positive CBH (Table 2). Of the 31 strains of V. cholerae O1, 12 (39%) were isolated from water and the 20-μm size fraction plankton, and the remaining 7 (23%) were isolated from 64-μm size fraction plankton samples. The single strain of V. cholerae O139 isolated in Bakerganj was from 64-μm size fraction plankton. The distribution of cholera vibrios by month is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 2.

Isolation and detection of Vibrio cholerae from water, 64-μm size fraction plankton, and 20-μm size fraction plankton samples collected from the aquatic environment of Bakerganja

| Site | Tech- nique | Result for sampleb

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004

|

2005

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| March

|

April

|

May

|

June

|

July

|

Aug.

|

Sept.

|

Oct.

|

Nov.

|

Dec.

|

Jan.

|

Feb.

|

March

|

April

|

May

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | ||

| 1 (pond) | Culturec | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CBHd | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | 39 | O1, 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 (pond) | Culture | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | |||||||||||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | 39 | O1 | 39 | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 (pond) | Culture | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | O1 | O1, 39 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | O1 | O1 | O1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 (pond) | Culture | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | O1 | C | C | C | C | C | C | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 (river) | Culture | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | O1 | O1 | O1 | C | C | O1 | O1 | C | C | C | C | C | O1 | O1 | O1 | C | C | C | ||||||||||||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 (pond) | Culture | C | C | C | C | O1 | O1 | O1 | C | C | C | C | O1 | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | O1 | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 (lake) | Culture | C | C | C | O1 | C | C | O1 | O1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | 39 | O1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 (lake) | Culture | C | C | C | C | C | O1 | O1 | O1 | C | O1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | O1 | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Samples were collected monthly from eight selected sites between March 2004 and May 2005.

W, water; 64, 64-μm size fraction plankton; 20, 20-μm size fraction plankton; C, culture positive for V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139; ND, not done; blank, negative; O1, V. cholerae serovar O1; 39, V. cholerae serovar O139.

Isolation of V. cholerae was done by selective enrichment followed by selective plating on TCBS and TTGA.

Colonies from LA were lifted onto nylon membranes for CBH, and toxigenic V. cholerae colonies from the master LA plate were picked (after regeneration of the colonies by reincubation at 37°C) based on positive CBH.

Environmental surveillance in Mathbaria.

Environmental samples were collected biweekly in Mathbaria between March 2004 and May 2005. Of the 495 samples (165 each from water and two size fractions of plankton) isolated by direct plating on L agar followed by CBH, selective enrichment, and culture, 41 (8%) yielded cholera vibrios, of which 15 (37%) were V. cholerae serovar O1 and 26 (63%) serovar O139 (Table 1). Of 41 cholera vibrios isolated from Mathbaria, 14 V. cholerae O1 and 21 V. cholerae O139 strains were isolated by employing enrichment and selective culture and 1 (2%) V. cholerae O1 strain and 5 (12%) V. cholerae O139 strains were isolated by culture on L agar following positive CBH (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Isolation and detection of Vibrio cholerae from water, 64-μm size fraction plankton, and 20-μm size fraction plankton samples collected from the aquatic environment of Mathbariaa

| Site | Tech- nique | Result for sampleb

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004

|

2005

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| March

|

April

|

May

|

June

|

July

|

Aug.

|

Sept.

|

Oct.

|

Nov.

|

Dec.

|

Jan.

|

Feb.

|

March

|

April

|

May

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | W | 64 | 20 | ||

| 1 | Culturec | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | C | C | C | C | C | C | O1 | O1 | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | ||||||||||

| CBHd | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Culture | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | 39 | 39 | 39 | C | C | C | |||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | O1, 39 | O1, 39 | O1 | O1, 39 | 39 | O1 | 39 | O1, 39 | O1, 39 | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | 39 | O1 | O1, 39 | 39 | O1, 39 | O1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Culture | C | C | 39 | ND | ND | ND | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | 39 | C | 39 | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | 39, O1 | 39 | 39, O1 | C | C | C | ||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 39 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | O1 | ND | ND | ND | O1 | O1 | O1, 39 | O1, 39 | 39 | 39 | O1, 39 | O1, 39 | O1, 39 | O1, 39 | O1 | O1, 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Culture | C | C | C | ND | ND | ND | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | 39 | 39 | 39 | C | C | C | ||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | 39 | ND | ND | ND | O1, 39 | O1 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | O1, 39 | O1 | O1 | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Culture | C | C | C | ND | ND | ND | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | 39 | C | C | O1 | O1 | O1 | C | C | C | C | C | C | 39 | C | 39 | ||||||||||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 39 | 39 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | ND | ND | ND | 39 | O1, 39 | O1 | 39 | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Culture | C | C | C | ND | ND | ND | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | C | 39 | 39 | 39 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| CBH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 39 | 39 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DFA | 39 | ND | ND | ND | O1, 39 | O1, 39 | O1, 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1, 39 | 39 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | O1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Samples were collected biweekly from six selected pond sites between March 2004, and May 2005.

W, water; 64, 64-μm size fraction plankton; 20, 20-μm size fraction plankton; C, culture positive for V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139; ND, not done; blank, negative; O1, V. cholerae serovar O1; 39, V. cholerae serovar O139.

Isolation of V. cholerae was done by selective enrichment followed by selective plating on TCBS and TTGA.

Colonies from LA were lifted onto nylon membranes for CBH, and toxigenic V. cholerae colonies from the master LA plate were picked (after regeneration of the colonies by reincubation at 37°C) based on positive CBH.

Immunochemical detection of cholera vibrios.

DFA detection of V. cholerae serovars O1 and O139 in Bakerganj and Mathbaria yielded results indicating variability in counts throughout the year.

As shown in Table 2, of the 360 environmental samples (120 each of water and of two plankton size fractions) collected in Bakerganj, 70 (19%) were V. cholerae, of which 59 (84%) were V. cholerae O1 and 11 (16%) were V. cholerae O139 Bengal. Of the 59 DFA-positive V. cholerae O1 strains, 20 (34%) were from the 64-μm size fraction plankton samples, 20 (34%) were from the 20-μm size fraction, and 19 (32%) were from water. Of the 11 V. cholerae O139 strains, 4 (36%) were from the 64-μm size fraction, 2 (18%) were from the 20-μm size fraction, and 5 (45%) were from water.

Of the 495 environmental samples (165 each of water and of two plankton size fractions) collected biweekly in Mathbaria, 141 (29%) V. cholerae strains were detected by DFA, of which 95 (67%) were V. cholerae O1 and 46 (33%) were O139 Bengal (data by month are shown in Table 3). Of the 95 DFA-positive V. cholerae O1 strains, 36 (38%) were from the 20-μm size fraction, 27 (28%) were from the 64-μm size fraction, and 32 (33%) were from water. Of the 46 DFA-positive V. cholerae O139 strains, 19 (41%) were from the 20-μm size fraction, 18 (39%) were from the 64-μm size fraction, and 9 (20%) were from water.

DFA results both for Bakerganj and Mathbaria showed V. cholerae O1 and O139 cells of various sizes and shapes, either as single cells or in biofilms (1). Although the numbers of V. cholerae O1 and O139 varied from month to month, the single cells or cluster of cholera vibrios was notable during cholera outbreaks, in both Bakerganj (Table 2) and Mathbaria (Table 3). Most significant was the fact that the cholera vibrios were present in the aquatic environment throughout the year.

DISCUSSION

Historically, cholera occurs each year in many geographic locations of Bangladesh, with two distinct seasonal peaks, one before and the other after the annual monsoon (14, 24, 31). Cholera epidemics are usually attributed to a single bacterial clone (12), except in a few cases, where more than one clone has occurred in the same geographic location (22). The corollary has been proposed that outbreaks begin from a point source and spread (12, 22). From epidemiological studies, it is known that cholera first strikes coastal villages before reaching inland (23, 25). Several studies have shown cholera epidemics to be related to environmental factors (8, 11, 19). However, the question remains as to what point source cholera spreads from and where the first clone of an epidemic appears.

Hospital surveillance data in Bakerganj have shown a marked seasonality in the numbers of cholera cases attributed to V. cholerae O1 biotype El Tor. A recent study conducted in Bakerganj (31) produced similar results on the incidences of V. cholerae O1 and O139. However, V. cholerae O139 was not linked to cholera cases in Bakerganj during the present study; that is, sporadic cases of cholera continued to occur during the interepidemic periods. Nevertheless, seasonality was clearly noted, beginning with the spring peak (before monsoon) and with a sharp rise in the number of cases during the fall peak (after monsoon). Based on surveillance data coupled with data published from an earlier study, Bakerganj can be considered to be an area where V. cholerae O139 is endemic, even though V. cholerae O139 was not isolated from any of the cholera cases in Bakerganj.

In contrast to results obtained in the previous ecological study, which reported poor recovery of cholera vibrios from water in Bakerganj (19), isolation of V. cholerae O1 biotype El Tor was achieved for 9% of the environmental samples. A significant proportion of these were isolated by direct culture, using positive CBH as the indication of the presence of V. cholerae and with subsequent intense culture methods being applied. Antibiotic-supplemented primary isolation media gave improved recovery of cholera vibrios, referred to as “conditionally viable environmental cells” (12), because conventional culture methods underestimate the conditionally viable environmental cells without use of antibiotic-supplemented media to suppress competition from other aquatic bacteria. Nonetheless, isolation of a large number of V. cholerae O1 El Tor strains from environmental samples collected in September 2004, followed by a large outbreak of cholera caused by V. cholerae O1 El Tor in October to December 2004, points to surface water as the habitat of V. cholerae of both serotypes (6, 7). Isolation of V. cholerae O1 from environmental samples was successful also in April 2005, when the first seasonal cholera outbreak for Bakerganj occurred.

The association of V. cholerae with planktonic copepods (7, 16, 18, 19) and aquatic flora (20) is now well established. However, successes in recoveries of cholera vibrios from water and the two plankton size fractions were essentially similar, with no significant increase in the abundance of V. cholerae in one or the other of the two plankton size fractions. Because a significant proportion of zooplankton eggs and nauplii were observed in the 20-μm size fraction, separation into phytoplankton and zooplankton by size was overridden by the presence of a dominance of zooplankton in both fractions.

The data obtained in this study clearly show V. cholerae to be native to the aquatic environment of Bakerganj (6, 7, 15, 17, 20, 29). The coexistence and environmental reservoir for the cholera vibrio serogroups O1 and O139 were confirmed by DFA detection (3, 18) in the environmental samples, even when the samples were collected during the interepidemic period.

This report is the first to provide surveillance data for the coastal ecosystem of Mathbaria, demonstrating two well-defined seasonal peaks of cholera (31, 34). The first seasonal peak of 2004, recorded in April to May, was caused by V. cholerae O1 biotype El Tor. The second peak, which began and ended in November 2004, was also caused by V. cholerae O1, as in Bakerganj. V. cholerae O139 was not recovered during these two yearly outbreaks of cholera in Mathbaria. The most important observation was, however, in March 2005; V. cholerae O139 reemerged as the sole cause of a large outbreak of cholera in Mathbaria, whereas the two immediate past outbreaks were attributed to V. cholerae O1. This resurgence of V. cholerae O139 as the causative agent of cholera in Mathbaria occurred when it had consistently been absent from all other endemic focal points in Bangladesh since 2002 (11, 30). Thus, a coastal reservoir for V. cholerae, in particular V. cholerae O139, is concluded to exist (31, 34).

The presence of V. cholerae O139 in the aquatic environment is particularly important. First, isolation of toxigenic V. cholerae O1 and O139 from surface water samples by culture is rarely, if ever, achieved (7, 16, 21). Second, V. cholerae O139 has remained consistently absent from areas of Bangladesh where cholera is endemic since it was last recorded in the spring of 2002 (11, 30). Third, in spite of being ctx+ (1) and metabolically active in the environment, V. cholerae O139 did not cause either of the two seasonal peaks in cholera cases in 2004. Thus, the coastal ecosystem, which is believed to be the traditional breeding ground for the cholera bacteria, serves as the ultimate reservoir of cholera vibrios of both serogroups (2, 4, 28, 34).

V. cholerae abundance appears to be triggered by environmental signals. The central role of a climatic factor(s) (8, 11, 19) in the clonal selection of an epidemic strain becomes evident from the reemergence of V. cholerae O1, which eventually displaced the epidemic clone of V. cholerae O139 and remained the sole causative agent of cholera in Mathbaria. Thus, there is ample reason to believe that V. cholerae O139 can displace the currently prevalent seventh-pandemic O1 El Tor strains and initiate an proposed eighth pandemic of cholera (2, 34).

The isolation of V. cholerae O1 and O139 by culture coupled with CBH and the year-round detection of culturable cells or viable but nonculturable cells by DFA (3, 5, 18), either as single cells or as clusters of cells within structured biofilms (1), leads to the conclusion that cholera bacteria (6, 7) are native to the coastal aquatic ecosystem of Bangladesh. The biofilms of V. cholerae observed during the present study are important in the life cycle of V. cholerae (23) and constitute a significant stage in its aquatic habitat.

Recent molecular studies have documented the establishment of variant alleles in V. cholerae O139 strains generated by lateral gene transfer during epidemics (13). Rapid genetic changes among V. cholerae O139 strains are also documented to have resulted in at least seven different ribotypes (10, 11). Our data for Mathbaria, coupled with observations reported earlier (11, 14, 19, 31, 34), show that V. cholerae O139 coexists with V. cholerae O1 in the aquatic environment. This study is therefore the first to show that while V. cholerae O139 remains present in low numbers or temporally absent from inland cholera foci (11), it shares the same niche with the seventh-pandemic V. cholerae O1 El Tor in the coastal aquatic ecosystem of Bangladesh.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by National Institutes of Health research grant 1R01 AI39 12901 under a subagreement between the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, the ICDDR, B, and the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute. The ICDDR, B, is supported by donor countries and agencies, which provide unrestricted support for its operations and research.

We acknowledge the contribution of the NIH epidemiological and environmental surveillance teams for their excellent support and commitment to the research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam, M., M. Sultana, G. B. Nair, R. B. Sack, D. A. Sack, A. K. Siddique, A. Ali, A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 2006. Toxigenic Vibrio cholerae in the aquatic environment of Mathbaria, Bangladesh. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2849-2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert, M. J., A. K. Siddique, M. S. Islam, A. S. G. Faruque, M. Ansaruzzaman, S. M. Faruque, and R. B. Sack. 1993. Large outbreak of clinical cholera due to Vibrio cholerae non-01 in Bangladesh. Lancet 341:704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brayton, P. R., and R. R. Colwell. 1987. Fluorescent antibody staining method for enumeration of viable environmental Vibrio cholerae O1. J. Microbiol. Methods 6:309-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cholera Working Group, ICDDR, B. 1993. Large epidemic of cholera-like disease in Bangladesh caused by Vibrio cholerae O139 synonym Bengal. Lancet 342:387-390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colwell, R. R., and A. Huq. 1994. Vibrios in the environment: viable but non-culturable Vibrio cholerae, p. 117-133. In I. K. Wachsmuth, P. A. Blake, and O. Oslvik (ed.), Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 6.Colwell, R. R., and W. M. Spira. 1992. The ecology of Vibrio cholerae, p. 107-127. In D. Barua and W. B. I Greenouh (ed.), Cholera. Plenum, New York, N.Y.

- 7.Colwell, R. R., and A. Huq. 1994. Environmental reservoir of Vibrio cholerae. The causative agent of cholera. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 740:44-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colwell, R. R. 1996. Global climate and infectious disease: the cholera paradigm. Science 274:2025-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dziejman, M., E. Balon, D. Boyd, C. M. Fraser, J. F. Heidelberg, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2002. Comarative genomic analysis of Vibrio cholerae: genes that correlate with cholera endemic and pandemic disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1556-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faruque, S. M., M. J. Albert, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1301-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faruque, S. M., N. Chowdhury, M. Kamruzzaman, Q. S. Ahmed, A. S. G. Faruque, M. A. Salam, T. Ramamurthy, G. B. Nair, A. Weintraub, and D. A. Sack. 2003. Reemergence of epidemic Vibrio cholerae O139, Bangladesh. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:1116-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faruque, S. M., M. Johirul Islam, Q. S. Ahmed, A. S. G. Faruque, D. A. Sack, G. B. Nair, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2005. Self-limiting nature of seasonal cholera epidemics: role of host-mediated amplification of phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:6119-6124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg, P., A. Ayadanian, D. Smith, J. G. Morris, Jr., G. B. Nair, and O. C. Stine. 2003. Molecular epidemiology of O139 Vibrio cholerae: mutation, lateral gene transfer, and founder flush. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:810-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glass, R. I., S. Becker, M. I. Huq, B. J. Stoll, M. U. Khan, M. H. Merson, J. V. Lee, and R. E. Black. 1982. Endemic cholera in rural Bangladesh, 1966-1980. Am. J. Epidemiol. 116:959-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta, N., S. Dewan, and S. Saini. 2005. Resurgence of Vibrio cholerae O139 in Rhotak. Indian J. Med. Res. 121:128-130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoshino, K., S. Yamasaki, A. K. Mukhopadhyay, S. Chakraborty, A. Basu, S. K. Bhattacharya, G. B. Nair, T. Shimada, and Y. Takeda. 1998. Development and evaluation of a multiplex PCR assay for rapid detection of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 20:201-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huq, A., R. R. Colwell, R. Rahaman, A. Ali, M. A. R. Chowdhury, S. Parveen, D. A. Sack, and E. R. Cohen. 1990. Detection of Vibrio cholerae O1 in the aquatic environment by fluorescent-monoclonal antibody and culture methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:2370-2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huq, A., R. R. Colwell, M. A. Chowdhury, B. Xu, S. M. Moniruzzaman, M. S. Islam, M. Yunus, and M. J. Albert. 1995. Coexistence of Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139 Bengal in plankton in Bangladesh. Lancet 345:1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huq, A., R. B. Sack, A. Nizam, Ira M. Longini, G. B. Nair, A. Ali, J. G. Morris, Jr., M. N. H. Khan, A. K. Siddique, M. Yunus, M. J. Albert, D. A. Sack, and R. R. Colwell. 2005. Critical factors influencing the occurrence of Vibrio cholerae in the environment of Bangladesh. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4645-4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Islam, M. S., B. S. Drasar, and R. B. Sack. 1993. The aquatic environment as a reservoir of Vibrio cholerae: a review. J. Diarrhoeal Dis. Res. 11:197-206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Islam, M. S., M. K. Hasan, M. A. Miah, M. Yunus, K. Zaman, and M. J. Albert. 1994. Isolation of Vibrio cholerae O139 synonym Bengal from the aquatic environment in Bangladesh: implications for disease transmission. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1684-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Islam, M. S., K. A. Talukder, N. H. Khan, Z. H. Mahmud, M. Z. Rahman, G. B. Nair, A. K. Siddique, M. Yunus, D. A. Sack, R. B. Sack, A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 2004. Variation of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 in the aquatic environment of Bangladesh and its correlation with the clinical strains. Microbiol. Immunol. 48:773-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kierec, K., and P. I. Watnick. 2003. The Vibrio cholerae O139 O-atigen polysaccharide is essential for Ca2+-dependent biofilm development in seawater. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:14357-14362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longini, I. M., M. Yunus, K. Zaman, A. K. Siddique, R. B. Sack, and A. Nizam. 2002. Epidemic and endemic cholera trends over a 33-year period in Bangladesh. J. Infect. Dis. 186:246-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nair, G. B., T. Ramamurthy, S. K. Bhattcharya, et al. 1994. Spread of Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal in India. J. Infect. Dis. 169:1029-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nandi, B., R. K. Nandi, S. Mukhopadhyay, G. B. Nair, T. Shimada, and A. C. Ghose. 2000. Rapid method for species-specific identification of Vibrio cholerae using primers targeted to the gene of outer membrane protein OmpW. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4145-4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Politzer, R. 1959. Cholera. Monograph series, no. 43. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 28.Ramamurthy, T., S. Garg, R. Sharma, S. K. Bhattacharya, G. Balakrish, T. Nair, T. Shimada, Y. Takeda, T. Karasawa, H. Kurazano, A. Pal, and Y. Takeda. 1993. Emergence of novel strains of Vibrio cholerae with epidemic potential in southern and eastern India. Lancet 341:703-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roszak, D. B., and R. R. Colwell. 1987. Survival strategies of bacteria in the natural environment. Microbiol. Rev. 51:365-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sack, D. A., R. B. Sack, G. B. Nair, and A. K. Siddique. 2004. Cholera (seminar). Lancet 363:223-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sack, R. B., A. K. Siddique, Ira M. Longini, Jr., A. Nizam, M. Yunus, M. S. Islam, J. G. orris, Jr., A. Ali, A. Huq, G. B. Nair, F. Qadri, S. M. Faruque, D. A. Sack, and R. R. Colwell. 2003. A 4-year study of the epidemiology of Vibrio cholerae in four rural areas of Bangladesh. J. Infect. Dis. 187:96-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddique, A. K., A. H. Baqui, A. Eusof, K. Haider, M. A. Hossain, I. Bashir, and aman. 1991. Survival of classic cholera in Bangladesh. Lancet 337:1125-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siddique, A. K., K. Zaman, K. Akram, R. Madsudy, A. Eusof, and R. B. Sack. 1994. Emergence of a new epidemic strain of V. cholerae in Bangladesh: an epidemiological study. J. Geog. Med. 46:147-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siddique, A. K., K. Akram, K. Zaman, P. Matsuddy, A. Eusof, and R. B. Sack. 1996. Vibrio cholerae O139: how great is the threat of a pandemic? Trop. Med. Int. Health 1:393-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tison, D. 1999. Vibrios, p. 497-506. In P. Murray, E. Baron, M. Pfaller, F. Tenover, and R. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 36.World Health Organization. 1974. WHO guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of cholera. Bacterial Disease Unit, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.