Abstract

Compost amendments to soils and potting mixes are routinely applied to improve soil fertility and plant growth and health. These amendments, which contain high levels of organic matter and microbial cells, can influence microbial communities associated with plants grown in such soils. The purpose of this study was to follow the bacterial community compositions of seed and subsequent root surfaces in the presence and absence of compost in the potting mix. The bacterial community compositions of potting mixes, seed, and root surfaces sampled at three stages of plant growth were analyzed via general and newly developed Bacteroidetes-specific, PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis methodologies. These analyses revealed that seed surfaces were colonized primarily by populations detected in the initial potting mixes, many of which were not detected in subsequent root analyses. The most persistent bacterial populations detected in this study belonged to the genus Chryseobacterium (Bacteroidetes) and the family Oxalobacteraceae (Betaproteobacteria). The patterns of colonization by populations within these taxa differed significantly and may reflect differences in the physiology of these organisms. Overall, analyses of bacterial community composition revealed a surprising prevalence and diversity of Bacteroidetes in all treatments.

The chemical, physical, and biological properties of soil in conjunction with various plant characteristics have profound effects on seed- and root-associated microbial communities (10, 11, 20, 23, 33, 34, 46, 53). Distinct microbial communities have been shown to develop on plant surfaces during different plant developmental stages, suggesting that a succession of microbial communities accompanies plant development (3, 10, 11, 29, 30, 34, 53). In addition to plant-specific effects, microbial communities associated with plants during development also can be influenced by exogenous amendments, such as compost, to plant soils or potting media (4, 25, 49). Compost amendment introduces copious amounts of organic matter and high numbers of microbial cells into soils or potting mixes. These microorganisms are often metabolically diverse, and some can degrade polymeric substances such as cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (5, 18, 42, 50). Saison et al. (43) recently reported that the community composition of soil-compost environments was influenced primarily by the organic-rich compost matrix rather than by the native compost microbiota. However, the extent to which such amendments can influence microbial communities in the rhizosphere and can serve as sources for rhizosphere populations has not been well characterized. Since composts are routinely applied to agricultural soils and potting mixes to improve soil fertility and plant growth and health, there is a need to characterize compost-plant interactions (15, 19, 24, 31).

In this study, we examined the bacterial community composition associated with cucumber seeds and seedling roots grown in compost-amended mixes by using PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and subsequent sequence analyses. Our objective was to follow the effect of compost amendment to potting mixes on the bacterial community compositions of seed and subsequent root surface communities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cucumber growth, sampling, and DNA extraction.

Three peat-based potting mixes were formulated as previously described (21). Briefly, sphagnum peat moss and perlite were combined with sawdust-incorporated cow manure compost (“sawdust compost”) or straw-incorporated cow manure compost (“straw compost”) in a 5:4:1 ratio, all on a volume basis (13). A “peat-only” treatment consisted of peat and perlite in a 6:4 ratio, also on a volume basis. Potting mixes were irrigated in 500-ml Styrofoam pots and incubated for 2 days prior to sowing. Two cucumber seeds (Cucumis sativus L. ‘Straight Eight’) were then sown in 500-ml Styrofoam pots and incubated under greenhouse conditions (22 to 27°C). Potting mix and plant material were sampled from three separate pots at three stages of plant development: seed germination (24 h postsowing), seedlings with fully extended cotyledons (1 week postsowing), and seedlings with four true leaves (3 weeks postsowing). Seed and roots were removed from each pot, shaken to remove loosely adhering potting mix, and washed twice with distilled water. Roots were homogenized using sterile razors and comprised rhizoplane, endosphere, and tightly adhering rhizospheric potting mix. Total DNA was extracted from these samples in triplicate using the UltraClean soil DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories, Inc., California).

DNA-based molecular analyses of bacterial community composition.

Two strategies were used to analyze bacterial communities in this study. First, for each sample, fragments of 16S rRNA genes were PCR amplified from extracted DNA with the “general bacterial” primer set 11F (5′-GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG-3′) (21)/907R (5′-CCG TCA ATT CMT TTG AGT TT-3′) (38) and subsequently PCR amplified with the “general bacterial for DGGE” primer set 341FGC (5′-CGC CCG CCG CGC CCC GCG CCC GTC CCG CCG CCC CCG CCC GCC TAC GGG AGG CAG CAG-3′) (38)/907R, as described previously (21). The general bacterial primer 11F, which fortuitously has a single mismatch with the cucumber plastid 16S rRNA gene sequence (and others) (matching plastid sequence, 5′-GTT CGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′; the mismatch is in boldface), was employed to reduce the otherwise pervasive PCR amplification of cucumber plastid sequences. Second, DNA extracts were also subject to PCR amplification with the “Bacteroidetes” primer set C319 (5′-GTA CTG AGA YAC GGA CCA-3′) (32)/907R (PCRs were conducted as described previously, with the exception that touchdown annealing temperatures were from 69°C to 65°C) and subsequently PCR amplified with the general bacterial for DGGE primer set (21). The resulting PCR products were then analyzed by DGGE.

DGGE analyses, band excision, cloning, and sequencing were conducted as described previously (21). Dominant bands from the general bacterial analyses of all samples were excised, and sequences recovered from these excised bands were submitted to the NCBI for BLAST analysis (2). Sequences were also examined by the CHECK_CHIMERA program located at the Ribosomal Database Project (14), and suspect sequences were removed from analyses.

Clustering analysis of DGGE profiles.

The similarity of bacterial community PCR-DGGE profiles of replicates of samples was estimated by cluster analysis, as described previously (21). Normalizations and analyses of DGGE gel patterns were done with BioNumerics software version 3.0 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). The normalized banding patterns were used to generate dendrograms by calculating the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient (51) and by UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages) clustering (47). This approach compares profiles based on both band position and intensity.

Sequence analyses.

Sequences of excised bands were aligned to known bacterial sequences using the “green genes” 16S rRNA gene database and alignment tool (16; http://greengenes.lbl.gov/). Aligned sequences and close relatives were imported and manually refined by visual inspection in the Mega software package version 3.1 (28). Neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees were constructed on the basis of 397 (Bacteroidetes) or 508 (Betaproteobacteria) positions of the 16S rRNA gene by using the Kimura two-parameter substitution model with complete deletion of gapped positions. The robustness of inferred tree topologies was evaluated by 1,000 bootstrap resamplings of the data, and nodes with bootstrap values of >70% are indicated.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences of the excised DGGE bands were filed under GenBank accession numbers AY341108 to AY341141, AY561506, and AY561507 (Table 1). Dominant bands from the general bacterial analyses of the potting mixes were sequenced and filed under GenBank accession numbers AY332573 to AY332578 and AY332586 to AY332603 (21).

TABLE 1.

Analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences recovered from DGGE bands excised and cloned from general bacterial analyses of potting mix, seed, and root samples

| Treatment or organelle and band | Accession no. | Sample (time postsowing) | Most similar sequence (by BLAST analysis)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Accession no. | % Similarity | Phylum | |||

| Peat | ||||||

| P1 | AY332573 | Mix (0) | Chryseobacterium formosense | AJ715377 | 99.82 | Bacteroidetes |

| P1-9 | AY341108 | Root (1 wk) | Potato plant root bacterium RC-III-62 | AJ252725 | 97.78 | Bacteroidetes |

| P2 | AY341109 | Root (1 wk) | Flavobacterium sp. strain R-20822 | AJ786788 | 94.24 | Bacteroidetes |

| P3 | AY332574 | Mix (0) | Rhizosphere soil bacterium RSI-35 | AJ252602 | 97.97 | Bacteroidetes |

| P5 | AY341110 | Root (3 wk) | Bacteriovorax stolpii | AY094131 | 98.73 | Deltaproteobacteria |

| P6a | AY332575 | Mix (0) | Uncultured bacterium clone O-CF-31 | AF443566 | 98.72 | Betaproteobacteria |

| P6b | AY332576 | Mix (0) | Uncultured Acidobacteria clone W1-1H | AY192198 | 97.20 | Acidobacterium |

| P9 | AY332577 | Mix (0) | Uncultured bacterium clone D | AJ459874 | 99.43 | Alphaproteobacteria |

| P10 | AY341111 | Seed (1 day) | Uncultured bacterium clone C-CF-23 | AF443568 | 97.81 | Betaproteobacteria |

| P12 | AY341112 | Root (1 wk) | Subseafloor sediment bacterial clone | AB177044 | 97.03 | Bacteroidetes |

| P13 | AY341113 | Root (1 wk) | Uncultured Bacteroidetes strain PRD18H08 | AY948070 | 93.63 | Bacteroidetes |

| P15 | AY341114 | Root (1 wk) | Uncultured soil bacterium clone TIIA5 | DQ297951 | 94.95 | Bacteroidetes |

| P16a | AY341115 | Seed (1 day) | Bacillus sp. strain HSCC 1649T | AB045097 | 95.99 | Firmicutes |

| P16-14 | AY341116 | Root (3 wk) | Sphingobacteriaceae bacterium Tibet-IIK55 | DQ177471 | 93.14 | Bacteroidetes |

| P17 | AY341117 | Root (3 wk) | Bacteroidetes bacterium LC9 | AY337604 | 96.29 | Bacteroidetes |

| P19-2 | AY332578 | Mix (0) | Betaproteobacterium Ellin152 | AF408994 | 96.20 | Betaproteobacteria |

| P19-4 | AY341118 | Seed (1 day) | Oxalobacter sp. strain 62AP11 | AB242751 | 99.64 | Betaproteobacteria |

| P20 | AY561506 | Mix (0) | Uncultured soil bacterium clone 845-2 | AY326591 | 97.64 | Gammaproteobacteria |

| PS5 | AY341119 | Root (1 wk) | Uncultured Bacteroidetes clone PRD18H08 | AY948070 | 93.15 | Bacteroidetes |

| Sawdust | ||||||

| S2 | AY332586 | Mix (0) | Uncultured Bacteroidetes clone CrystalBog5D8 | AY792301 | 96.67 | Bacteroidetes |

| S3 | AY341120 | Root (1 wk) | Uncultured bacterium BIjii2 | AJ318153 | 91.01 | Bacteroidetes |

| S5 | AY332587 | Mix (0) | Chryseobacterium formosense | AJ715377 | 98.52 | Bacteroidetes |

| S6 | AY332588 | Mix (0) | Fluviicola taffensis strain RW262 | AF493694 | 97.05 | Bacteroidetes |

| S7 | AY332589 | Mix (0) | Sphingobacterium composta | AB244764 | 96.13 | Bacteroidetes |

| S8 | AY332590 | Mix (0) | Uncultured bacterium clone PE37 | AY838493 | 93.87 | Bacteroidetes |

| ST-9 | AY332591 | Mix (0) | Uncultured bacterium clone C7-K9 | AJ421162 | 88.95 | Bacteroidetes |

| S9 | AY561507 | Seed (1 day) | Uncultured bacterium O-CF-31 | AF443566 | 99.27 | Betaproteobacteria |

| S10 | AY332592 | Mix (0) | Exiguobacterium sp. strain NIPHL090904/K2 | AY748915 | 100.00 | Firmicutes |

| S11 | AY332593 | Mix (0) | Uncultured gammaproteobacterium clone AKYG1610 | AY921806 | 97.27 | Gammaproteobacteria |

| S13 | AY332594 | Mix (0) | Uncultured bacterium clone CYCU-NirS-16S-NH-123 | DQ010317 | 98.89 | Bacteroidetes |

| S14 | AY341121 | Seed (1 day) | Uncultured Bacteroidetes strain BIsii5 | AJ318181 | 95.84 | Bacteroidetes |

| S24 | AY341122 | Root (3 wk) | Uncultured bacterium BIjii2 | AJ318153 | 92.42 | Bacteroidetes |

| S26 | AY341123 | Root (3 wk) | Uncultured bacterium HP1A92 | AF502211 | 98.70 | Bacteroidetes |

| S27 | AY341124 | Root (3 wk) | Uncultured Bacteroidetes strain BIsii5 | AJ318181 | 94.61 | Bacteroidetes |

| S28 | AY341125 | Root (1 wk) | Uncultured Bacteroidetes clone EB 19 | AM168117 | 97.58 | Bacteroidetes |

| S30 | AY341126 | Root (1 wk) | Sporocytophaga myxococcoides | AJ310654 | 98.86 | Bacteroidetes |

| S32 | AY341127 | Root (3 wk) | Uncultured betaproteobacterium clone CW13 | AY956663 | 100.00 | Betaproteobacteria |

| S33 | AY341128 | Seed (1 day) | Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SAFR-173 | DQ124701 | 94.76 | Gammaproteobacteria |

| S34 | AY341129 | Root (1 wk) | Methylophilus sp. strain C2 | AY436789 | 98.37 | Betaproteobacteria |

| Straw | ||||||

| T2 | AY332595 | Mix (0) | Chryseobacterium formosense | AJ715377 | 97.78 | Bacteroidetes |

| T4 | AY332596 | Mix (0) | Uncultured Bacteroidetes clone CrystalBog5D8 | AY792301 | 96.45 | Bacteroidetes |

| T5 | AY332597 | Mix (0) | Bacteroidetes bacterium R2-Dec-MIB-3 | AB126976 | 97.04 | Bacteroidetes |

| T7 | AY332598 | Mix (0) | Uncultured compost bacterium 4b | AY489030 | 98.98 | Bacteroidetes |

| T8 | AY332599 | Mix (0) | Uncultured bacterium PHOS-HE36 | AF314435 | 93.73 | Chlorobi |

| T9 | AY332600 | Mix (0) | Uncultured bacterium clone C7-K9 | AJ421162 | 88.76 | Bacteroidetes |

| T10 | AY332601 | Mix (0) | Uncultured bacterium clone Urania-2B-06 | AY627565 | 98.91 | Betaproteobacteria |

| T12 | AY332602 | Mix (0) | Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria | AM039952 | 96.91 | Gammaproteobacteria |

| T15 | AY332603 | Mix (0) | Uncultured bacterium clone CYCU-NirS-16S-NH-123 | DQ010317 | 98.51 | Bacteroidetes |

| T16 | AY341130 | Seed (1 day) | Sphingobacterium composta | AB244764 | 96.68 | Bacteroidetes |

| T17 | AY341131 | Seed (1 day) | Rhizobium sp. strain Kus-7 | AF510381 | 98.66 | Alphaproteobacteria |

| T18 | AY341132 | Seed (1 day) | Betaproteobacterium Ellin152 | AF408994 | 97.99 | Betaproteobacteria |

| T19 | AY341133 | Seed (1 day) | Uncultured bacterium clone B5 | AB246720 | 98.17 | Firmicutes |

| T20 | AY341134 | Root (1 wk) | Uncultured bacterium HP1A92 | AF502211 | 97.96 | Bacteroidetes |

| T21 | AY341135 | Root (1 wk) | Uncultured Bacteroidetes strain BIti15 | AJ318185 | 94.27 | Bacteroidetes |

| T24 | AY341136 | Root (1 wk) | Paenibacillus sp. strain DS-1 | DQ129555 | 99.63 | Firmicutes |

| T26a | AY341137 | Root (3 wk) | Marine bacterium MBIC1357 | AB032514 | 92.79 | Bacteroidetes |

| T26b | AY341138 | Root (3 wk) | Methylophilus sp. strain C2 | AY436789 | 99.45 | Betaproteobacteria |

| T27 | AY341139 | Root (3 wk) | Methylophilus sp. strain C2 | AY436789 | 97.99 | Betaproteobacteria |

| T28 | AY341140 | Root (3 wk) | Uncultured bacterium clone 010B-B12 | AY662047 | 98.13 | Betaproteobacteria |

| Cucumber plastid | AY341141 | NAa | Cucumis sativus chloroplast | AJ970307 | 97.85 | Plastids |

NA, not applicable.

RESULTS

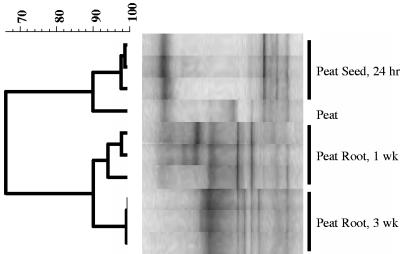

Triplicate DNA samples of potting mix from the time of sowing, seed, and 1- and 3-week roots were analyzed by PCR-DGGE using general bacterial primers. The similarity of PCR-DGGE profiles from replicate samples was assessed as previously described (21), and a representative analysis is presented in Fig. 1. The profiles of the replicate samples were found to be highly similar, with UPGMA Pearson correlation coefficients (r) of at least 92%, with most values higher. Due to the high similarity of the replicate profiles, a single representative sample from each time point and treatment was selected for further analysis.

FIG. 1.

A representative dendrogram depicting the similarity of profiles of bacterial communities generated from PCR-DGGE analyses of replicate samples of seed (24 h) and root (1 and 3 weeks) from cucumber grown in the peat-only potting mix. Bacterial community profiles were generated by PCR-DGGE analysis as described in the text. The UPGMA algorithm was applied to a similarity matrix of Pearson product moment correlation coefficients (r values) generated from the DGGE banding patterns.

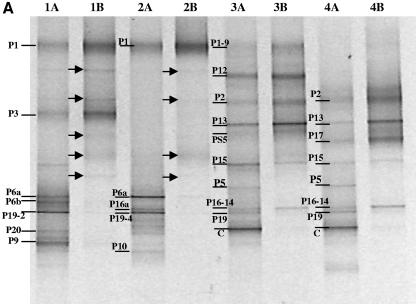

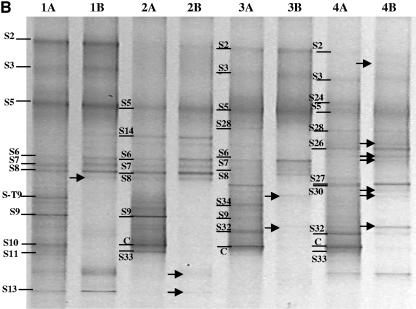

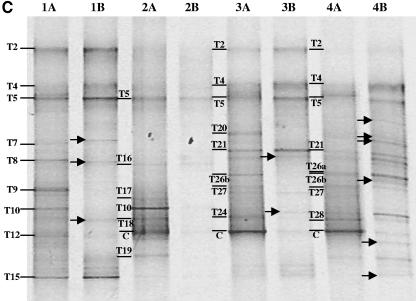

For each representative DNA sample, a dual-primer-set, nested-PCR-DGGE analysis was performed to evaluate the bacterial community composition. Both general bacterial (11F/907R) and Bacteroidetes-specific (C319/907R) PCR amplicons were subject to nested PCR with the same general bacterial primers suitable for DGGE analyses (341FGC/907R). The resulting PCR products, approximately 500 to 550 bp in size, were analyzed by DGGE as described above (Fig. 2). Most of the visible bands detected by DGGE were excised and sequenced from the general bacterial analyses. The most similar sequences, by BLAST analyses, to those recovered are presented in Table 1, and phylogenetic analyses of Oxalobacteraceae and Bacteroidetes sequences are presented in Fig. 3 and 4, respectively.

FIG.2.

PCR-DGGE analysis of partial 16S rRNA genes amplified from the peat-only (A), sawdust compost (B), and straw compost (C) treatments. For each treatment, PCR-DGGE profiles for potting mix from the time of sowing (lanes 1), seed surface after 24 h of incubation in the potting mix (lanes 2), roots after 1 week of growth in the potting mix (lanes 3), and roots after 3 weeks of growth in the potting mix (lanes 4) are shown. DNA samples were initially amplified with a general bacterial primer set (lanes A) or with a Bacteroidetes primer set (lanes B) and then subjected to nested PCR with general bacterial primers appropriate for DGGE analysis, as described in the text. Excised, cloned, and sequenced bands are labeled and are discussed in the text. Populations detected only in the Bacteroidetes-enhanced PCR-DGGE analyses are indicated by arrows.

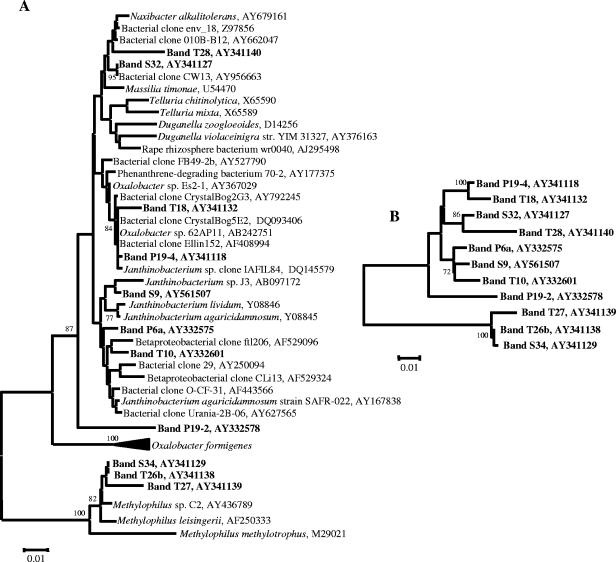

FIG. 3.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees of detected betaproteobacterial populations. Bootstrapped neighbor-joining trees were generated with 1,000 resamplings, and nodes with bootstrap values of greater than 70% are indicated, as described in the text. Band numbers refer to bands isolated from DGGE analyses. The scale bars represent 0.01 substitution per nucleotide position. A: Phylogenetic tree of betaproteobacterial sequences recovered from DGGE bands and most similar sequences as identified by BLAST. B: Phylogenetic tree of betaproteobacterial sequences recovered from DGGE bands alone.

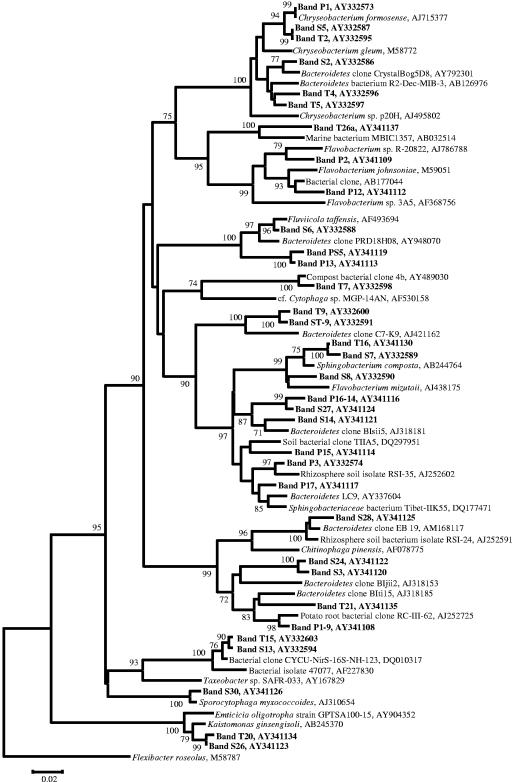

FIG. 4.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of Bacteroidetes populations detected in the study. Bootstrapped neighbor-joining trees were generated with 1,000 resamplings, as described in the text. Band numbers refer to bands isolated from DGGE analyses. Nodes with bootstrap values of greater than 70% are labeled. The scale bar represents 0.02 substitution per nucleotide position.

The Bacteroidetes-specific PCR-DGGE analyses were highly specific to the phylum and did not amplify non-Bacteroidetes sequences. Bands detected in general bacterial PCR-DGGE analyses (lanes labeled A in Fig. 2A to C) were inferred to represent bacteria from the phylum Bacteroidetes when a band in the adjacent lane to the right (lanes labeled B in Fig. 2A to C) migrated to the same vertical position. This is possible because (i) the PCR yields were derived from the same genomic DNA sample, (ii) the PCR fragment for DGGE was the same size and at the same location within the rRNA gene, (iii) the internal general bacterial primers 341F and 907R were checked in silico for potential bias against the Bacteroidetes and were found to perfectly match approximately 94% of Bacteroidetes sequences in the ARB database (substantially more than the Bacteroidetes primer C319) (see reference 32 for a description of primer targets), and (iv) all band sequences were recovered from the general bacterial analyses, not the Bacteroidetes-specific analyses, demonstrating that the bands in the general analyses migrating to the same vertical locations as bands in the Bacteroidetes analyses were indeed Bacteroidetes and not merely comigrating DNA fragments (Table 1; Fig. 4). In this study, such inferences were highly reliable, as indicated by sequence analyses of bands excised and sequenced from the general bacterial DGGE analyses. However, due to the difficulty in designing a single primer to amplify rRNA gene sequences from all Bacteroidetes (32), some Bacteroidetes were detected with general bacterial analyses but not with the Bacteroidetes-specific analyses (e.g., bands ST-9 and T9 [Fig. 2B and C and 4]).

In all three treatments, the number of populations detected by PCR-DGGE analysis on the seed surfaces was lower than that detected in the potting mix prior to sowing. Many of the populations detected on the seeds were also detected in the potting mix from the respective treatments. Despite the differences in the compositions of the bacterial communities of the three potting mixes, particularly between the compost-amended and peat-only treatments (21), the seed surfaces in all treatments were colonized by bacteria from the genus Chryseobacterium (bands P1, S5, and T5) and by one or two populations belonging to the family Oxalobacteraceae (bands P6a, P19-4, S9, T10, and T18).

The root bacterial community profiles differed significantly from the initial potting mix and seed surface community profiles in all treatments (Fig. 2A to C). Within each treatment, root communities had many populations in common (represented by bands P2, P5, P13, P15, P16-14, and P19; bands S2, S3, S5, S30, and S32; and bands T2, T4, T5, T21, T26b, and T27 for peat-only, sawdust compost, and straw compost treatments, respectively), but these populations were generally not detected in potting mix and seed samples. Within treatments, those bacteria that were detected in potting mix, seed, and root samples belonged to the genus Chryseobacterium and the family Oxalobacteraceae. For example, in the peat-only treatment, of the two Oxalobacteraceae populations detected on the seed surface (represented by bands P6a and P19-4), a band at the position of P19-4 was detected on the roots at 1 and 3 weeks. This band was confirmed to be a member of the Oxalobacteraceae (data not shown). Likewise, in the sawdust and straw compost treatments, Chryseobacterium populations (bands S5 and T5) were detected in all samples from potting mix to root surface at 3 weeks, and other Chryseobacterium populations (bands S2, T2, and T4) were detected in the potting mix and on the roots at 1 and 3 weeks. As with the peat-only treatment, Oxalobacteraceae populations were also detected on the root surfaces in compost-amended treatments. In the sawdust compost treatment, two Oxalobacteraceae populations were detected (bands S9 and S32). Band S9, detectable on the seed surface and the root at 1 and 3 weeks, migrated to the same position on the DGGE gel as bands P6a and T10, while band S32, detected only on the root surface at 24 h and 3 weeks, migrated to the same position as P19 and T28 (data not shown). In the straw compost treatment, two Oxalobacteraceae populations (bands T10 and T18) were detected on the seed, while only a single population (band T28) was detected on the root at 3 weeks.

In this study, 60 sequences (including cucumber plastid) were obtained from bands excised from DGGE gels. Based on sequence analyses, 44 of these sequences were 95% or more similar, and 2 were less than 90% similar (bands ST-9 and T9, Bacteroidetes by phylogenetic analyses), to published sequences. The inferred bacterial populations were unevenly distributed among five taxa, i.e., Bacteroidetes (34 sequences), Proteobacteria (19 sequences), Firmicutes (4 sequences), Acidobacteria (1 sequence), and Chlorobi (1 sequence). Sequences affiliated with the phylum Bacteroidetes were the most frequently recovered and revealed the presence of a large diversity of bacteria belonging to this phylum (Fig. 4). The application of Bacteroidetes-specific analyses revealed the presence of additional diversity within some of the samples (Fig. 2A to C). Interestingly, the presence of additional Bacteroidetes diversity was observed primarily in the potting mix and seed surface in the peat-only treatment and on the root samples from the compost treatments. In the peat-only treatment, the bacterial community profiles of roots at 1 and 3 weeks, as determined by the general bacterial DGGE analysis, were nearly completely composed of Bacteroidetes, except for the cucumber plastid, a Bacteriovorax population (band P5), and an Oxalobacteraceae population (band P19).

The detected Betaproteobacteria were predominantly from the family Oxalobacteraceae, and phylogenetic analyses of Oxalobacteraceae revealed three groupings of bands recovered from all three treatments (bands P6a, S9, and T10; P19-4 and T18; and S32 and T28). With the exception of the grouping of P19-4 and T18, bootstrap values above 70% could not be established initially for these groups due to the short sequence length and high similarity of the sequences (Fig. 3A). When the band sequences were analyzed alone, strong support was given for the clustering of band P19-4 with T18, S32 with T28, and P6a with S9 and T10 (Fig. 3B).

DISCUSSION

Compost amendment to soils and potting mixes can significantly modify plant-associated microbial communities of plants grown in such media (25, 49). In addition to shifts associated with plant development, plant-associated microbial communities can be influenced by the chemical, physical, and biological properties of soils and potting mixes amended with compost. In this study, seed surfaces were colonized largely by bacterial populations detectable in the potting mixes at the time of sowing. In all three treatments, the seed-colonizing bacterial communities included bacteria from the genus Chryseobacterium and the family Oxalobacteraceae. Since the seeds are the first plant surfaces to be colonized, there is a great deal of interest in the provenance of such organisms and their eventual persistence and colonization of growing root surfaces. However, Normander and Prosser (39) observed a disparity between seed and root microbial communities and proposed that this difference was an indication that emerging plant roots are colonized by soilborne, rather than seed-borne, microorganisms. In our study, the persistence of seed-colonizing populations varied by taxon and with potting mix treatment, although, overall, many of the seed-colonizing populations were not detected in root samples. For example, root communities in the peat-only treatment shared only a single population with the seed (an Oxalobacteraceae population).

Oxalobacteraceae populations were present in seed and root samples in the compost treatments as well. Phylogenetic analyses revealed that although all the recovered sequences were more than 95% similar, two different clades were detected on seed surfaces while a third clade was detected in root samples. The detection of phylogenetically distinct, but closely related, populations on seeds and roots suggests a physiological difference that may explain their environmental distribution. Furthermore, these Oxalobacteraceae were either absent or only faintly detectable in general bacterial analyses of potting mix samples taken at the later time points, suggesting that their persistence was a result of rhizosphere competence rather than abundance in the potting mix (data not shown). Members of the Oxalobacteraceae are aerobic, flagellated, root- or soil-dwelling bacteria that are capable of degradation of a variety of organic molecules, including chitin, and are easily mistaken for pseudomonads (8, 9, 48, 52). These characteristics may explain their persistence in the root environment.

In addition to Oxalobacteraceae, bacteria belonging to the genus Chryseobacterium were detected on seed surfaces 1 day after sowing in all treatments. This genus (family Flavobacteriaceae, phylum Bacteroidetes) consists of bacteria that are nonmotile, aerobic, pigmented, and capable of saprophytic or parasitic growth (7). In this study, the distribution of Chryseobacterium varied significantly with treatment; in the peat-only treatment they were not detected in root samples, while in root samples from compost treatments certain Chryseobacterium spp. were among the most persistent. In contrast to the case for the Oxalobacteraceae spp., we observed that the detection of Chryseobacterium spp. on plant surfaces largely mirrored their detection in potting mix samples from the same time points (data not shown). While motility has been shown to be important for root colonization by pseudomonads, the persistence of the nonmotile Chryseobacterium spp. on root surfaces may be a result of a reservoir of organisms maintained in the compost-amended potting mix, although transport via plant growth or water percolation may also have played a role (17, 35). The provenance and persistence of the Chryseobacterium spp. and the Oxalobacteraceae are currently being further investigated to determine if composts are sources and factors for maintenance of these organisms in the root environment.

Overall, molecular analyses revealed a surprising dominance and diversity of Bacteroidetes. Bacteroidetes are known for their utilization of macromolecules, including proteins and polysaccharides such as cellulose and chitin (6, 26, 32, 41). Bacteroidetes, including Chryseobacterium spp., have been previously detected in composted materials (1, 12, 21, 37), in soil environments (52, 54), and in association with plant surfaces (22, 26, 27, 29, 30, 33, 36, 40, 44, 45). We have consistently recovered Chryseobacterium sequences directly from these and other cow manure composts produced in the same location (Ohio Agriculture Research and Development Center, Ohio State University, Wooster). Certainly, cultivation-independent molecular techniques often reveal a greater abundance and diversity of Bacteroidetes than cultivation-based analyses of the same samples, perhaps due to the difficulty of isolating some members of this phylum (27). The application of general bacterial and Bacteroidetes primer sets, nested with the same internal general primer set, proved to be a rapid and reliable technique for detection of bacteria from this phylum. Since Bacteroidetes can be large contributors to nutrient cycling in plant environments via production of degradative enzymes (26), we believe that this technique will prove to be a useful tool in plant and other environmental studies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by research grant US-3108-99 from BARD (the U.S.-Israel Binational Agriculture Research and Development Fund), by the Negev Foundation Ohio-Israel agriculture initiative, and by a Baron de Hirsch travel grant to S.J.G.

We greatly appreciate commentary on the manuscript by Jaak Ryckeboer and Maya Ofek.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfreider, A., S. Peters, C. C. Tebbe, A. Rangger, and H. Insam. 2002. Microbial community dynamics during composting of organic matter as determined by 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. Comp. Sci. Util. 10:303-312. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baudoin, E., E. Benizri, and A. Guckert. 2002. Impact of growth stage on the bacterial community structure along maize roots, as determined by metabolic and genetic fingerprinting. Appl. Soil Ecol. 19:135-145. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazin, M. J., P. Markham, and E. M. Scott. 1990. Population dynamics and rhizosphere interactions, p. 99-127. In J. M. Lynch (ed.), The rhizosphere. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., West Sussex, United Kingdom.

- 5.Beffa, T., M. Blanc, L. Marilley, J. L. Fischer, P. F. Lyon, and M. Aragno. 1996. Taxonomic and metabolic microbial diversity during composting, p. 149-161. In M. De Bertoldi, P. Sequi, B. Lemmes, and T. Papi (ed.), The science of composting. M. Chapman and Hall, London, United Kingdom.

- 6.Bernardet, J.-F., and Y. Nakagawa. 2003. An introduction to the family Flavobacteriaceae. In M. Dworkin (ed.), The prokaryotes: an evolving electronic resource for the microbiological community, 3rd ed., release 3.15. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y. [Online.] http://link.springer-ny.com/link/service/books/10125/.

- 7.Bernardet, J.-F., Y. Nakagawa, and B. Holmes. 2002. Proposed minimal standards for describing new taxa of the family Flavobacteriaceae and emended description of the family. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:1049-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodour, A. A., J. M. Wang, M. L. Brusseau, and R. M. Maier. 2003. Temporal change in culturable phenanthrene degraders in response to long-term exposure to phenanthrene in a soil column system. Environ. Microbiol. 5:888-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowman, J. P., L. I. Sly, A. C. Hayward, Y. Spiegel, and E. Stackebrandt. 1993. Telluria mixta (Pseudomonas mixta Bowman, Sly, and Hayward 1988) gen. nov., comb. nov., and Telluria chitinolytica sp. nov., soil-dwelling organisms which actively degrade polysaccharides. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buyer, J. S., D. P. Roberts, and E. Russek-Cohen. 1999. Microbial community structure and function in the spermosphere as affected by soil and seed type. Can. J. Microbiol. 45:138-144. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buyer, J. S., D. P. Roberts, and E. Russek-Cohen. 2002. Soil and plant effects on microbial community structure. Can. J. Microbiol. 48:955-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cahyani, V. R., K. Matsuya, S. Asakawa, and M. Kimura. 2003. Succession and phylogenetic composition of bacterial communities responsible for the composting process of rice straw estimated by PCR-DGGE analysis. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 49:619-630. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Changa, C. M., P. Wang, M. E. Watson, H. A. J. Hoitink, and F. C. Michel. 2003. Assessment of the reliability of a commercial maturity test kit for composted manures. Comp. Sci. Util. 11:125-143. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole, J. R., B. Chai, T. L. Marsh, R. J. Farris, Q. Wang, S. A. Kulam, S. Chandra, D. M. McGarrell, T. M. Schmidt, G. M. Garrity, and J. M. Tiedje. 2003. The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): previewing a new autoaligner that allows regular updates and the new prokaryotic taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:442-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Brito Alvarez, M. A., S. Gagne, and H. Antoun. 1995. Effect of compost on rhizosphere microflora of the tomato and on the incidence of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:194-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeSantis, T. Z., I. Dubosarskiy, S. R. Murray, and G. L. Andersen. 2003. Comprehensive aligned sequence construction for automated design of effective probes (CASCADE-P) using 16S rDNA. Bioinformatics 19:1461-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Weert, S., H. Vermeiren, I. H. Mulders, I. Kuiper, N. Hendrickx, G. V. Bloemberg, J. Vanderleyden, M. R. De, and B. J. Lugtenberg. 2002. Flagella-driven chemotaxis towards exudate components is an important trait for tomato root colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 15:1173-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz-Ravina, M., M. J. Acea, and T. Carballas. 1989. Microbiological characterization of four composted urban refuse. Biol. Waste 30:89-100. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dick, W. A., and E. L. McCoy. 1993. Enhancing soil fertility by addition of compost, p. 622-644. In H. A. J. Hoitink and H. M. Keener (ed.), Science and engineering of composting: design, environmental, microbiological and utilization aspects. Renaissance Publications, Worthington, Ohio.

- 20.Duineveld, B. M., G. A. Kowalchuk, A. Keijzer, J. D. van Elsas, and J. A. van Veen. 2001. Analysis of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere of chrysanthemum via denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA as well as DNA fragments coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:172-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green, S. J., F. C. Michel, Jr., Y. Hadar, and D. Minz. 2004. Similarity of bacterial communities in sawdust- and straw-amended cow manure composts. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 233:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallmann, J., A. Quadt-Hallmann, W. F. Mahaffee, and J. W. Kloepper. 1997. Bacterial endophytes in agricultural crops. Can. J. Microbiol. 43:895-914. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heuer, H., R. M. Kroppenstedt, J. Lottmann, G. Berg, and K. Smalla. 2002. Effects of T4 lysozyme release from transgenic potato roots on bacterial rhizosphere communities are negligible relative to natural factors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1325-1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoitink, H. A. J., and M. Boehm. 1999. Biocontrol within the context of soil microbial communities: a substrate-dependent phenomenon. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 37:427-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inbar, E., S. J. Green, Y. Hadar, and D. Minz. 2005. Competing factors of compost concentration and proximity to root affect the distribution of streptomycetes. Microb. Ecol. 50:73-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansen, J. E., and S. J. Binnerup. 2002. Contribution of cytophaga-like bacteria to the potential of turnover of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus by bacteria in the rhizosphere of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Microb. Ecol. 43:298-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaiser, O., A. Puhler, and W. Selbitschka. 2001. Phylogenetic analysis of microbial diversity in the rhizoplane of oilseed rape (Brassica napus cv. Westar) employing cultivation-dependent and cultivation-independent approaches. Microb. Ecol. 42:136-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahaffee, W. F., and J. W. Kloepper. 1997. Bacterial communities of the rhizosphere and endorhiza associated with field-grown cucumber plants inoculated with a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium or its genetically modified derivative. Can. J. Microbiol. 43:344-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahaffee, W. F., and J. W. Kloepper. 1997. Temporal changes in the bacterial communities of soil, rhizosphere, and endorhiza associated with field-grown cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Microb. Ecol. 34:210-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandelbaum, R., Y. Hadar, and Y. Chen. 1988. Composting of agricultural wastes for their use as container media—effect of heat-treatments on suppression of Pythium aphanidermatum and microbial activities in substrates containing compost. Biol. Waste 26:261-274. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manz, W., R. Amann, W. Ludwig, M. Vancanneyt, and K. H. Schleifer. 1996. Application of a suite of 16S rRNA-specific oligonucleotide probes designed to investigate bacteria of the phylum Cytophaga-Flavobacter-Bacteroides in the natural environment. Microbiology 142:1097-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marilley, L., and M. Aragno. 1999. Phylogenetic diversity of bacterial communities differing in degree of proximity of Lolium perenne and Trifolium repens roots. Appl. Soil Ecol. 13:127-136. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marschner, P., G. Neumann, A. Kania, L. Weiskopf, and R. Lieberei. 2002. Spatial and temporal dynamics of the microbial community structure in the rhizosphere of cluster roots of white lupin (Lupinus albus L.). Plant Soil 246:167-174. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mawdsley, J. L., and Burns, R. G. 1994. Root colonization by a Flavobacterium species and the influence of percolating water. Soil Biol. Biochem. 26:861-870. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McSpadden Gardener, B. B., and D. M. Weller. 2001. Changes in populations of rhizosphere bacteria associated with take-all disease of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4414-4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michel, F. C., Jr., T. J. Marsh, and C. A. Reddy. 2002. Bacterial community structure during yard trimmings composting, p. 25-42. In H. Insam, N. Riddech, and S. Klammer (ed.), Microbiology of composting. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 38.Muyzer, G., E. C. de Waal, and A. G. Uitterlinden. 1993. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:695-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Normander, B., and J. I. Prosser. 2000. Bacterial origin and community composition in the barley phytosphere as a function of habitat and presowing conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4372-4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olsson, S., and P. Persson. 1999. The composition of bacterial populations in soil fractions differing in their degree of adherence to barley roots. Appl. Soil Ecol. 12:205-215. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riemann, L., and A. Winding. 2001. Community dynamics of free-living and particle-associated bacterial assemblages during a freshwater phytoplankton bloom. Microb. Ecol. 42:274-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryckeboer, J., J. Mergaert, K. Vaes, S. Klammer, D. De Clercq, J. Coosemans, H. Insam, and J. Swings. 2003. A survey of bacteria and fungi occuring during composting and self-heating processes. Ann. Microbiol. 53:349-410. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saison, C., V. Degrange, R. Oliver, P. Millard, C. Commeaux, D. Montange, and X. Le Roux. 2006. Alteration and resilience of the soil microbial community following compost amendment: effects of compost level and compost-borne microbial community. Environ. Microbiol. 8:247-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato, K., and J.-Y. Jiang. 1996. Gram-negative bacterial flora on the root surface of wheat (Triticum aestivum) grown under different soil conditions. Biol. Fert. Soils 23:273-281. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmalenberger, A., and C. C. Tebbe. 2002. Bacterial community composition in the rhizosphere of a transgenic, herbicide-resistant maize (Zea mays) and comparison to its non-transgenic cultivar Bosphore. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 40:29-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smalla, K., G. Wieland, A. Buchner, A. Zock, J. Parzy, S. Kaiser, N. Roskot, H. Heuer, and G. Berg. 2001. Bulk and rhizosphere soil bacterial communities studied by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis: plant-dependent enrichment and seasonal shifts revealed. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4742-4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sneath, P. H. A., and R. R. Sokal. 1973. Numerical taxonomy. W.H. Freemand and Co., San Francisco, Calif.

- 48.Spiegel, Y., E. Cohn, S. Galper, E. Sharon, and I. Chet. 1991. Evaluation of a newly isolated bacterium, Pseudomonas chitinolytica sp nov for controlling the root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne javanica. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 1:115-125. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tiquia, S. M., J. Lloyd, D. A. Herms, H. A. J. Hoitink, and F. C. Michel, Jr. 2002. Effects of mulching and fertilization on soil nutrients, microbial activity and rhizosphere bacterial community structure determined by analysis of TRFLPs of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 21:31-48. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tiquia, S. M., J. H. C. Wan, and N. F. Y. Tam. 2002. Microbial population dynamics and enzyme activities during composting. Comp. Sci. Util. 10:150-161. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vauterin, L., and P. Vauterin. 1992. Computer-aided objective comparison of electrophoresis patterns for grouping and identication of microorganisms. Eur. Microbiol. 1:37-41. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wery, N., U. Gerike, A. Sharman, J. B. Chaudhuri, D. W. Hough, and M. J. Danson. 2003. Use of a packed-column bioreactor for isolation of diverse protease-producing bacteria from antarctic soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1457-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wieland, G., R. Neumann, and H. Backhaus. 2001. Variation of microbial communities in soil, rhizosphere, and rhizoplane in response to crop species, soil type, and crop development. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5849-5854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamaguchi, S., and M. Yokoe. 2000. A novel protein-deamidating enzyme from Chryseobacterium proteolyticum sp. nov., a newly isolated bacterium from soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3337-3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]