Abstract

Litter from the chicken industry can present several environmental challenges, including offensive odors and runoff into waterways leading to eutrophication. An economically viable solution to the disposal of waste from chicken houses is treatment to produce a natural, granulated fertilizer that can be commercially marketed for garden and commercial use. Odor of the final product is important in consumer acceptance, and an earthy odor is desirable. By understanding and manipulating the microbial processes occurring during this process, it may be possible to modify the odors produced. Geosmin and related volatiles produced by soil actinomycetes are responsible for earthy odors, and actinomycetes are likely to be present in the composting manure. Bacterial communities at each stage of the process were analyzed by culturing studies and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). The processing steps changed the culturable bacterial community, but the total community was shown by DGGE to be stable throughout the process. A local agricultural soil was analyzed in parallel as a potential source of geosmin-producing actinomycetes. This agricultural soil had higher microbial diversity than the compost at both the culturable and the molecular levels. Actinomycete bacteria were isolated and analyzed by AromaTrax, a gas chromatography-olfactometry system. This system enables the odor production of individual isolates to be monitored, allowing for rational selection of strains for augmentation experiments to improve the odor of the final fertilizer product.

The worldwide consumption of poultry and poultry products is increasing. According to the U.S. Egg and Poultry Association the total number of broiler chickens produced in the United States in 2004 was 8.74 billion, an increase of 3% from 2003 (www.poultryegg.org/EconomicInfo/index.html). The steady increase in poultry production has resulted in an increase in wastes associated with chicken production. Chicken litter is a waste product from broiler birds reared for meat production and is comprised of manure, bedding material (sawdust, wood shavings, straw, and peanut or rice hulls), and feathers. The most common use for this waste litter is direct application to agricultural land. Poor management of land application has long been recognized as detrimental to the environment and fish, animal, and human health (8, 12, 20, 22). A report by the U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry in 1997 (23) identified nutrient runoff from livestock and poultry as the greatest pollutant in 60% of rivers and streams identified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as having impaired water quality. Because of the large number of broiler farms on Maryland's Eastern Shore, the water quality of the Chesapeake Bay is threatened by nutrient runoff unless good waste management procedures are followed. Recent algal blooms focused attention on the issue of wastes from the Delmarva (Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia) poultry industries. The direct application method not only creates nutrient runoff pollution but causes odor pollution as well. Odors can be offensive to surrounding residents and may cause irritation of both the lower and upper respiratory tracts in people with long-term exposure (22). Strong odors have been reported to intensify the symptoms of people with asthma or allergies (2). An extensive report on the odors from broiler farms in Australia by the Rural Industries Research and Development Committee (http://www.rirdc.gov.au/reports/CME/00-2.pdf) has shown that aerobic microbial metabolism processes in the litter produce nitrogen-containing odorants such as ammonia, amines, indole, skatol, and volatile fatty acids as well as sulfur-containing odorants such as hydrogen sulfide, dimethyl disulfide, and dimethyl trisulfide. In an extensive review of poultry waste management (24), it was stated that “alternative strategies for mitigating the impact of odors released from poultry manures during production, storage, treatment, and land application will be required in the future.” The combination of increased production of waste and environmental concerns with poor land management and offensive odor production has prompted research into an economically viable alternative to direct application of chicken litter to agricultural land. Chicken litter is rich in nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus. A process has been developed by Perdue AgriRecycle which takes raw litter from broiler houses and generates a natural granulated fertilizer which can be marketed for commercial and garden use. Accumulated litter is removed from the broiler houses every 2 years and transported to the recycling plant. In this study, litter incoming from the broiler houses to the processing facility is referred to as fresh litter. Litter is piled and stored for 3 days to start the composting process, after which the litter is turned and piled for a further 7 days. The litter is then passed through a shredding process to form a fine powder. The powdered litter is compressed into pellets, granulated, and treated with an antidust agent and anise fragrance. The final product is sold as fertilizer, leading to widespread distribution and slow release of nutrients, therefore controlling runoff and eliminating waterway pollution. Odor of the final product is important to consumers, and a current problem is an offensive odor upon long-term storage in warehouse inventories. Odor-masking techniques such as the addition of anise fragrance can help with this problem, but the production of a more “natural” earthy odor is desirable. A recent study by Coates et al. (4) attempted to control hog waste odor by stimulating the removal of malodorous compounds by Fe(III) addition and augmentation with a Fe(III)-reducing microbe.

Previous studies of the microbial communities in chicken litter have focused on culturable communities and the detection of possible pathogens or antibiotic resistance markers within the litter (13, 14, 16). Culturable bacterial counts in litter ranging from 107 to 109 CFU per gram (dry weight) of litter have been reported (18, 19). This study combines a culturable and molecular approach to evaluate the complete microbial community throughout the recycling process. Odors of the litter and final product are measured, and modification of offensive odors is attempted by microbial supplementation. The earthy aroma of natural soil is due to the production of a volatile compound called geosmin (7). Geosmin and related volatiles are produced by actinomycete bacteria in the genus Streptomyces which are abundant in soils. Spores of Streptomyces spp. were added to the fertilizer production process to assess whether the odor of the final product could be improved by this approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

Samples were taken from the AgriRecycle plant (Seaford, Delaware) at each point of the recycling process: initial composting pile (fresh), 3-day-old compost, 10-day-old compost, shredded litter, pellets, granules, and antidust- and anise-treated final product. Samples were also taken from an adjoining agricultural field in which a crop of soybeans was being raised. Samples were maintained at ambient temperature (ca. 30°C) and processed within 4 h of collection.

Culturable isolates.

Viable counts were measured by dilution plating onto plate count agar (Difco, Detroit, MI). Actinomycete isolation media ISP2 medium (Difco) and R2A (Difco) agar, supplemented with a final concentration of 10 μg ml−1 nalidixic acid, 10 μg ml−1 cycloheximide, and 25 μg ml−1 nystatin, were inoculated for specific isolation of actinomycetes. Selected isolates were identified by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. DNA was extracted from these isolates by using the Ultra Clean Microbial DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories Inc., Carlsbad, CA) and identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Spore production.

Spores from isolates that produced earthy aromas were harvested for augmentation of litter. Pure cultures were grown on solid ISP2 medium (Difco) incubated at 30°C until sporulation. Spores and mycelium were harvested by scraping material from plates and storing it as a dry powder at 4°C.

Nucleic acid extraction.

DNA was extracted from chicken litter samples by a method utilizing chemical and mechanical lysis and CsCl gradient purification. Stringent purification of DNA was required to remove humic acids and other contaminants from the litter samples prior to PCR amplification. Samples (1 g) were resuspended in 5 ml of SET buffer (2% sucrose, 50 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8) containing 10 mg/ml−1 lysozyme in a screw-cap 15-ml centrifuge tube and incubated at 37°C for 1 h with shaking. Sterile zirconia beads (1.0-mm and 0.1-mm diameter; 1 g of each) (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK) were added and tubes attached to a vortex platform shaker on full speed for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged at 2,800 × g for 10 min and supernatants collected in clean 50-ml centrifuge tubes. Pellets were resuspended in 5 ml phosphate-buffered saline buffer (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) containing 20 mg proteinase K and incubated at 37°C for 30 min prior to transfer to 65°C for 1 h with shaking. Samples were centrifuged at 2,800 × g for 10 min, pooled, and extracted with phenol and chloroform until the aqueous phase was clear although some pigmentation was still apparent. Nucleic acids were precipitated with addition of a 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate and 2 volumes of ethanol at −20°C for at least 2 h. Pellets were resuspended in Tris-EDTA (TE) and supplemented with CsCl to a concentration of 1 g/ml. Ethidium bromide was added, and samples were sealed in Quick-Seal tubes (Beckman, Fullerton, CA) centrifuged in a Vti65 rotor (Beckman) at 194,000 × g for 16 h. DNA bands were visualized under UV light, removed, and dialyzed against TE. DNA was ethanol precipitated, dried, and resuspended in TE buffer.

Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE).

Primers P2 and P3 (17) were used to amplify a 195-bp region of the rRNA gene corresponding to position 341 to position 534 in the 16S rRNA gene of Escherichia coli. PCR amplification was performed on 100 ng of DNA with Platinum Taq (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 25 pmol of each primer. The cycling conditions were a hot start at 94°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of 92°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min and a final extension step of 72°C for 5 min. Thermal cycling was performed in a PTC-200 cycling system (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). The final PCR product was loaded onto a 6% acrylamide gel with a denaturing gradient of 40 to 70%. Electrophoresis was performed using the D-Code system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in 1× TAE (20 mM Tris acetate, 10 mM sodium acetate, 0.5 mM EDTA) at a constant temperature of 60°C and 60 V for 16 h. The gel was stained with 1× SYBR green (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR) for 10 min and visualized with the Typhoon 9410 image system (Amersham Biosciences, United Kingdom).

Amplification, cloning, and sequencing of 16S rRNA gene fragments.

PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was performed using 100 ng DNA with universal 16S rRNA gene primers 8-27f and 1492r (11) specific for 16S rRNA genes from bacteria. Three replicate reactions were done for each sample using high-fidelity Taq polymerase to reduce errors during the amplification (Platinum Taq High Fidelity; Invitrogen) and a low cycle number (25 cycles). Cycling conditions were a hot start at 94°C for 5 min; 20 cycles of 92°C for 30 s, 48°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min; and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The samples were pooled and gel purified using the QIAGEN gel extraction kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and cloned into E. coli using the TOPO XL kit (Invitrogen). A negative-control reaction was performed where no litter-extracted DNA was added. Resultant clones were sequenced by Lark Technologies Bioscience Corporation (Houston, TX) using the M13 forward primer. Clones from which >500 bp of sequence from the 5′ end of the 16S rRNA gene were obtained were included in the phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Sequences were compared to those in GenBank using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (1) to determine approximate phylogenetic affiliations. Chimeric sequences were identified using the program CHECK_CHIMERA (15). Partial sequences were manually compiled and aligned using Phydit software (3). The evolutionary tree was generated using the neighbor-joining (21), Fitch-Margoliash (6), and maximum parsimony (10) algorithms in the PHYLIP package (5). Evolutionary distance matrices for the neighbor-joining and Fitch-Margoliash methods were generated as described by Jukes and Cantor (9). The robustness of inferred tree topologies was evaluated after 1,000 bootstrap resamplings of the neighbor-joining data.

Headspace gas chromatography using SPME.

Headspace gas chromatography is an analytical technique designed to measure volatile compounds contained in a less volatile matrix like chicken litter. It is used in determinations such as alcohol in blood (e.g., in drunk driving cases), residual solvents in food packaging and pharmaceuticals, and flavor volatiles and organic solvents responsible for water pollution. Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) involves a fiber coated with a liquid (polymer), a solid (sorbent), or a combination of the two. The fiber coating removes the compounds (e.g., aromas) from the sample by absorption in the case of liquid coatings or adsorption in the case of solid coatings. In this study the odors are absorbed onto a thin film of polymer and then released by thermal desorption into a gas chromatograph. We employed a commercial product that is designed exclusively for aroma analysis. The AromaTrax (Microanalytics, Round Rock, TX) is an integrated multidimensional gas chromatography-olfactory system designed for the analysis of aromas, flavors, and odors. The SPME film collects enough material in approximately 2 cubic millimeters of absorbing material to permit the detection of all pertinent aroma compounds at an odor sniff port. The desorbed SPME volatiles are injected into and separated by a single-column (30-m by 0.53-mm Solgel-WAX) gas chromatographic system and detected by mass spectrometry (MS) and the human nose at a sniff port (olfactory detector). The configuration of the gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (GC/MS) permits the odors to be detected organoleptically and simultaneously quantified and identified. In order to perform these functions an open split interface was added to the GC/MS configuration. The open split interface permits the use of the higher-flow, higher-capacity megabore columns while ensuring that the exit of the analytical column is maintained at atmospheric pressure, thus ensuring optimized chromatographic performance regardless of the high vacuum at the mass spectrometer. The use of the open split interface also makes it possible to vary the split ratio between the olfactory port and the mass spectrometer. For the current application the flow to each of the open split interface ports was 2 cm3 min−1. To help in the organoleptic identification, the output of the olfactory port was humidified with 10 cm3 min−1 of water-saturated breathing air.

Sample preparation.

Each sample (10 g) was placed in a clear borosilicate (I-CHEM, Rockwood, TN) environmental sampling vial with a screw-top Teflon septum cap. Each vial was equilibrated for 24 h at 30°C in a constant-temperature incubator. Volatiles were sampled from the headspace of each vial using a 2-cm SPME filter assembly (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA) coated with an 85-μm carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane Stableflex phase. The SPME fiber in its steel 23-gauge needle housing was placed in the split/splitless injector fitted with a Merlin Microseal septum (Merlin Instrument Company, California) equilibrated at 240°C and run at a 2:1 split ratio with a split flow of 14.0 ml min−1. Upon exposure of the fiber, the purge was initiated to allow the volatiles to pass into the analytical column (30-m by 0.53-mm Solgel-Wax [SGE, Texas]) via a straight 1.2-mm glass liner (SGE). The column was maintained at 40°C for 3 min, and the oven was then programmed to increase to 200°C at 7°C min−1. The linear gas velocity was approximately 48 cm s−1 set to constant flow. The olfactory port was maintained at 165°C to prevent condensation of volatiles prior to olfactory detection. Data collection was begun simultaneously with the purge, allowing the volatile compounds into the GC/MS and the commencement of olfactometry. The compounds of interest were identified by comparison with the National Institute of Standards and Technology library of 129,000 compounds. Assignments were confirmed where possible by SPME sampling of vials spiked with standards prepared from the pure compounds. Dimethyl disulfide and geosmin were obtained as liquids from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Calibration curves were obtained for each component, and these data provided the basis for the calculation of the amount of each substance found in each sample.

Odor modification of litter samples.

Two approaches were used in attempts to modify the odor of chicken litter, enzymatic treatment and supplementation with Streptomyces spores. A 10% (wt/wt) and 1% (wt/wt) addition of a commercially available enzyme catalyst, Zymo-Cat (Sorbent Technologies Inc., Atlanta, GA), was applied to litter and incubated at 60°C for 2 h. The effect of augmentation with spores from strains SOY1 and SOY3 was tested separately. A 10-g sample of litter was treated with a 100-μl solution containing 1 × 105 spores plus the dispersant 0.01% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). Negative controls were untreated litter. One set of litter samples was treated in this way and left dry for 6 weeks. These mixtures were incubated at 30°C. After 6 weeks, the dry samples were wetted by addition of 20% (vol/wt) water.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the sequences are DQ206904 to DQ206961 for the fresh clones and DQ203244 to DQ203290 for the pellet clones.

RESULTS

Culturable community.

The results of the culturable counts from the fresh litter on plate count agar were generally higher (7.5 × 106 CFU g−1) than those in normal agricultural soil from the adjoining soybean field (6.2 × 105 CFU g−1). The highest number of culturable bacteria was apparent at the 10-day point (2.4 × 107 CFU g−1). A significant drop in culturable bacteria is apparent after the processing to form pellets with culturable counts of 2.3 × 103 CFU g−1 present in treated granules (Table 1, steps D and E in the process).

TABLE 1.

Numbers of culturable bacteria on heterotrophic plate count agar (PCA) and actinomycete-specific agar (ISP2 and R2A)a

| Sampling point | No. of bacteria (CFU/ml) on agar type:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | ISP2 | R2A | |

| A | 7.5 × 106 | 7.5 × 103 | 7.1 × 103 |

| B | 6.3 × 105 | 2.9 × 104 | 2.8 × 104 |

| P for A vs B | 0.03 | 0.0005 | 0.0008 |

| C | 2.4 × 107 | 9.6 × 103 | 7.8 × 103 |

| P for B vs C | 0.03 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| D | 1.1 × 107 | 1.3 × 104 | 5.9 × 103 |

| P for C vs D | 0.16 | 0.91 | 0.52 |

| E | 6.6 × 103 | 9.3 × 103 | 1.0 × 104 |

| P for D vs E | 0.003 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| F | 3.3 × 103 | 1.0 × 104 | 9.9 × 103 |

| P for E vs F | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.58 |

| G | 2.3 × 103 | 7.9 × 103 | 1.1 × 104 |

| P for F vs G | 0.67 | 0.22 | 0.40 |

Values shown are the means of triplicate samples for each point in the recycling process: fresh litter (A), 3-day pile (B), 10-day pile (C), shredded matter (D), pellets (E), granules (F), and coated granules (G). A two-tailed P test was performed to test significance between sampling points, and these significant differences are shown in boldface.

On the actinomycete selective media, the same general trend was observed with numbers of culturable bacteria decreasing after pellet processing although numbers of putative actinomycetes did not drop as much as the total heterotrophic bacterial count. On both actinomycete isolation media, the diversity of morphotypes obtained from the chicken litter samples was quite low, with only four or five distinctive colony morphologies being apparent. The agricultural soil sample yielded a higher diversity of approximately 10 morphotypes. Actinomycete isolates from the agricultural soybean field site were tested by AromaTrax analysis for the production of geosmin and related volatiles. Two dominant actinomycetes, designated SOY1 (DQ186638) and SOY3 (DQ186639), were isolated from the soybean field site and identified by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis as Streptomyces spp. On the basis of BLAST analysis of 16S rRNA gene analysis of partial sequence (750 bp), SOY1 was most closely related to Streptomyces venezuelae (99% identity) and SOY3 was most closely related to Streptomyces ambifaciens (98% identity).

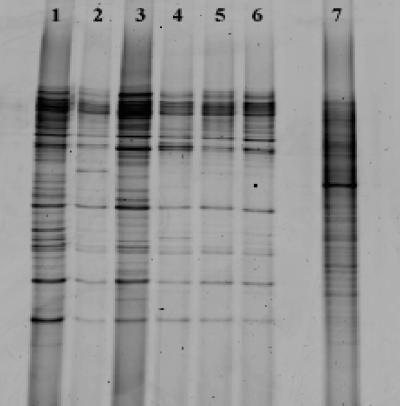

DGGE analysis.

The DGGE banding pattern generated from the chicken litter was remarkably similar to those for samples taken throughout the process. A similar banding pattern was seen in the fresh sample and in the final granulated product (Fig. 1). DGGE patterns generated from total community DNA extracted from the soybean field samples gave a complex banding pattern typical of diverse environmental soil, indicating a much higher microbial diversity than that present in the chicken litter samples.

FIG. 1.

DGGE analysis of different stages of the recycling process. Lanes: 1, crude litter; 2, 3-day pile; 3, 10-day pile; 4, shredded material; 5, pellets; 6, final processed product; 7, soybean field.

16S rRNA gene clone library analysis.

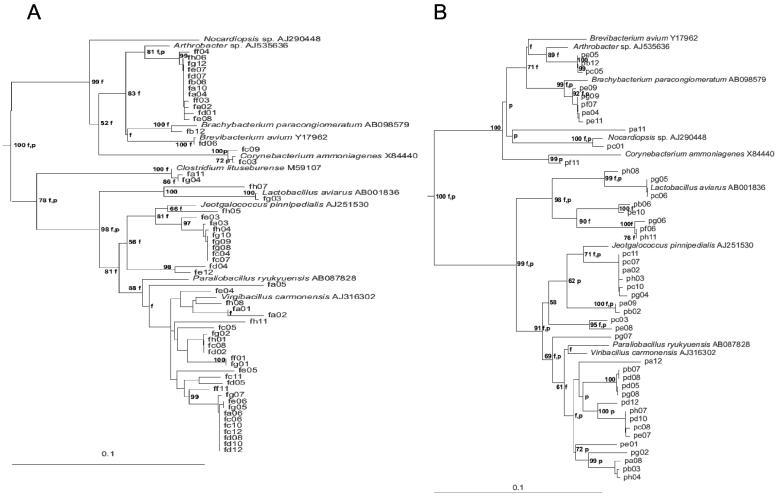

Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA gene clone libraries from fresh litter and pelleted product showed that these communities were dominated by gram-positive bacteria of both low-G+C and high-G+C groups. Seventy-two and 28% of clones in the fresh litter and 72 and 24% of clones in the pellet samples were assigned to low-G+C and high-G+C groups, respectively (Fig. 2). The similarity observed between these two libraries is consistent with the community stability observed in the DGGE analysis.

FIG. 2.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees from analysis of ca. 600 bp of 16S rRNA gene sequence of clones in the libraries constructed from total DNA extracted from fresh chicken litter (A) and from processed pelleted fertilizer (B). “F” and “P” indicate branches that were also found using the Fitch-Margoliash and maximum parsimony methods, respectively. The numbers at the roots indicate bootstrap support based on a neighbor-joining analysis of 1,000 resampled data sets and are given as percentages with only values of >50% shown. The scale bar represents 0.1 substitution per nucleotide position. E. coli was used as the outgroup.

Odor analysis.

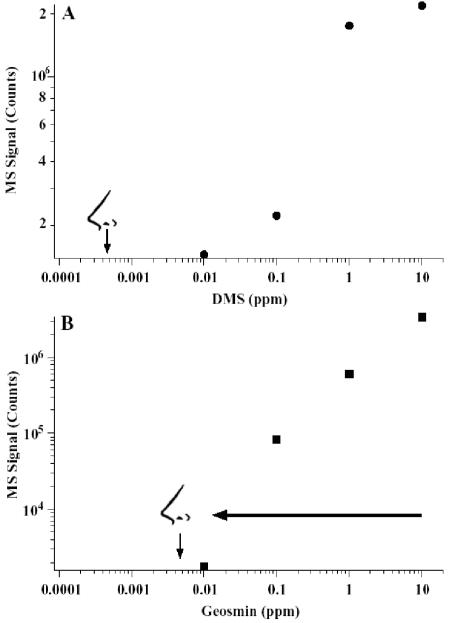

GC/MS response curves for dimethyl sulfide (DMS; elution time, 2.03 min) and geosmin (elution time, 21 min) are shown in Fig. 3. The MS signal is proportional to input (ppm) over nearly 4 orders of magnitude. The detection limit at the olfactory port spanned the same range with a lower detection limit (50% lower with geosmin and nearly an order of magnitude lower with DMS) (Fig. 3). When 10 ppm geosmin was added to processed chicken litter, the MS signal was suppressed nearly 1,000-fold (indicated in Fig. 3 by an arrow), presumably due to a matrix suppression effect.

FIG. 3.

GC/MS response curves for dimethyl sulfide (A) and geosmin (B). The arrow indicates the change in response when 10 ppm geosmin is added to 10 g of processed chicken litter. The olfactory symbol (nose) represents the lower detection limit observed at the olfactory port for these two molecules.

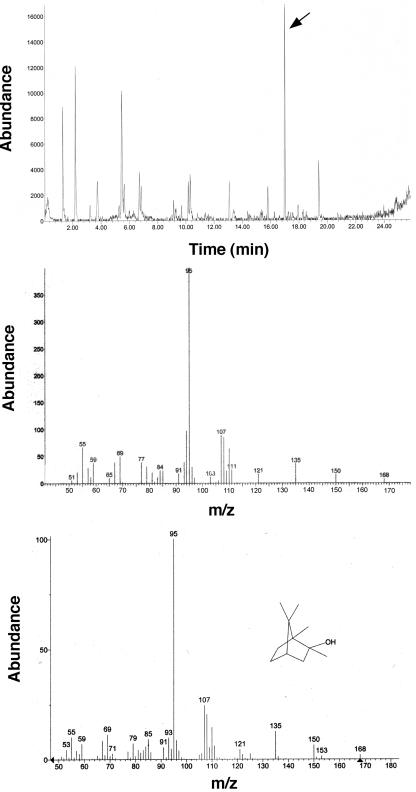

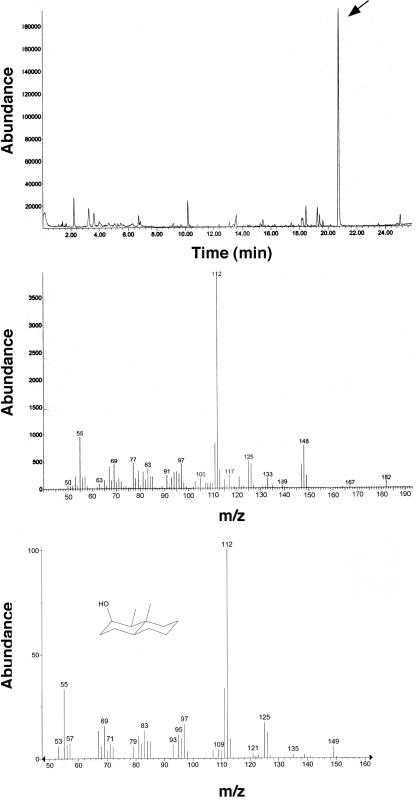

The aroma profiles of the isolates from the agricultural site, Streptomyces sp. strain SOY1 and Streptomyces sp. strain SOY3, were generated. Streptomyces sp. strain SOY1 was shown to produce a geosmin-related compound, 2-methylisoborneol (Fig. 4), and Streptomyces sp. strain SOY3 was shown to produce geosmin (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Top panel: gas chromatogram of SPME adsorbed volatiles from isolate SOY1. Middle and bottom panels: the mass spectrum of the volatile at 16.9 min (middle) is compared with authentic 2-methylisoborneol (bottom).

FIG. 5.

Top panel: gas chromatogram of SPME adsorbed volatiles from isolate SOY3. Middle and bottom panels: the mass spectrum of the volatile at 20.9 min (middle) is compared with authentic geosmin (bottom).

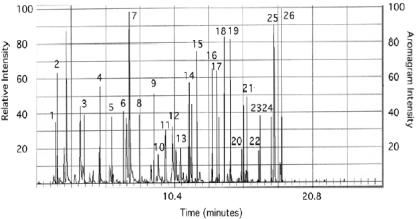

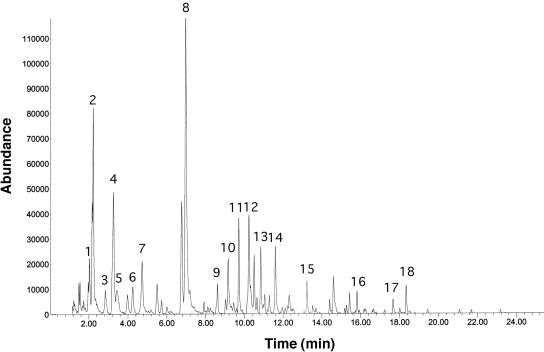

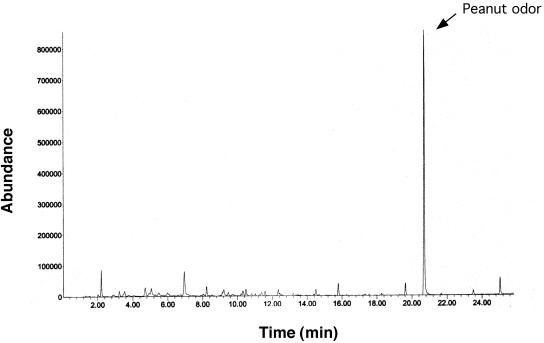

The fresh litter showed a complex odor profile (Fig. 6), and several peaks were recognized as unpleasant and foul at the sniff port (Table 2) and generally corresponded with peaks of reduced sulfur compounds such as DMS. Analysis of the finished product (Fig. 7) showed that the processing did not reduce offensive odors. Major peaks from this profile are identified in Table 3. Addition of geosmin to fresh litter at 10 ppm did not result in an earthy smell due to severe suppression by the litter matrix, similarly to what we saw with the processed litter (Fig. 3). Treatment with the enzymatic deodorizer Zymo-Cat at 1% and 10% resulted in complete removal of offensive odors and generated a new “peanut-like” aroma (Fig. 8). Addition of spores from the Streptomyces sp. strains SOY1 and SOY3 did not alter odor production of the fresh litter even after long-term incubation. Addition of 20% water after 6 weeks of incubation of the spore and litter mix resulted in production of an earthy odor after incubation for 1 week although no significant changes were noticed in the aroma profile and no peaks could be identified as geosmin or 2-methylisoborneol.

FIG. 6.

Odor profile (solid histogram) of fresh litter overlaid on the headspace gas chromatogram. The descriptions of odors from the AromaTrax sniff port are presented in Table 2, with peak numbers in Table 2 corresponding to the numbers used in this figure.

TABLE 2.

Descriptions of odors from fresh litter samples detected at the AromaTrax sniff porta

| Peak no. | Descriptor | Start time (min) | Event width (min) | Relative intensity | Areab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unknown | 1.42 | 0.02 | 35 | 69 |

| 2 | Unknown | 1.53 | 0.04 | 63 | 251 |

| 3 | Unknown | 3.57 | 0.02 | 39 | 77 |

| 4 | Banana | 4.73 | 0.03 | 55 | 164 |

| 5 | Ethanol | 5.63 | 0.03 | 38 | 113 |

| 6 | Foul | 6.52 | 0.02 | 41 | 81 |

| 7 | Herbaceous | 6.99 | 0.03 | 41 | 122 |

| 8 | Acetaldehyde | 7.71 | 0.02 | 39 | 77 |

| 9 | Unknown | 8.81 | 0.03 | 51 | 152 |

| 10 | Citrus | 11.42 | 0.04 | 45 | 179 |

| 11 | Nutty | 11.51 | 0.02 | 57 | 113 |

| 12 | Unknown | 11.69 | 0.03 | 45 | 134 |

| 13 | Buttery | 12.09 | 0.04 | 75 | 299 |

| 14 | Foul | 13.25 | 0.04 | 65 | 259 |

| 15 | Earthy | 13.61 | 0.02 | 64 | 127 |

| 16 | Unknown | 13.76 | 0.03 | 37 | 110 |

| 17 | Earthy | 14.14 | 0.05 | 83 | 414 |

| 18 | Unknown | 14.62 | 0.06 | 82 | 491 |

| 19 | Unknown | 15.49 | 0.02 | 19 | 37 |

| 20 | Earthy | 15.62 | 0.03 | 44 | 131 |

| 21 | Earthy | 15.88 | 0.03 | 49 | 146 |

| 22 | Unknown | 16.71 | 0.02 | 18 | 35 |

| 23 | Soapy | 16.81 | 0.03 | 38 | 113 |

| 24 | Unknown | 17.67 | 0.03 | 37 | 110 |

| 25 | Foul | 17.81 | 0.14 | 90 | 1257 |

| 26 | Unknown | 18.44 | 0.05 | 99 | 494 |

Peak numbers are the same as in Fig. 6.

Area = event width × relative intensity × 100.

FIG. 7.

Headspace gas chromatography of final granulated litter. The identities of compounds were determined by MS, and these are presented in Table 3, with peak numbers in Table 3 corresponding to the numbers used in this figure.

TABLE 3.

Identified compounds in the headspace of the final granulated littera

| Peak no. | Compound |

|---|---|

| 1 | Octane |

| 2 | Dimethyl sulfide |

| 3 | Glutaraldehyde |

| 4 | 2-Butanone |

| 5 | 2-Methylbutanone |

| 6 | 2-Ethyl furan |

| 7 | Pentanal |

| 8 | Hexanal |

| 9 | Penten-3-ol |

| 10 | 2-Heptanone |

| 11 | Pyrazine |

| 12 | 1-Pentanol |

| 13 | Methylpyrazine |

| 14 | Hexanenitrile |

| 15 | Dimethyl trisulfide |

| 16 | 1-Nitrohexane |

| 17 | Butanoic acid |

| 18 | 2-Methyl hexanoic acid |

Peak numbers correspond to peaks shown in Fig. 7.

FIG. 8.

Headspace gas chromatography of fresh chicken litter after treatment with Zymo-Cat enzymatic deodorizer at 1% (wt/vol).

DISCUSSION

The variation in numbers of culturable bacteria at the different stages of the process is likely due to changes in oxygen concentrations and to heat treatments. The litter piles can reach >70°C in less than 4 hours. Oxygen is introduced into the litter piles when they are turned after 3 days and after the shredding process. The high numbers of bacteria at these stages of the process could be the result of growth stimulation of aerobic bacteria throughout the pile by this oxygenation. The dramatic drop in culturable bacteria which is recorded after the processing to form pellets is probably due to the heating of the samples to ca. 71°C for 45 min during this step, which would kill most heterotrophic bacteria. The less marked decrease in numbers of actinomycetes may be due to the presence of heat-resistant spores of these bacteria, which germinate when conditions become favorable for growth. Numbers of culturable bacteria from the fresh litter were higher than numbers recorded from agricultural soil although the agricultural soil gave a greater diversity of colony morphologies.

The decreases in counts of culturable bacteria were not reflected in changes in patterns generated by DGGE. These patterns for all stages of the process were strikingly similar, suggesting that the total microbial community changed very little from beginning to end of the process. DGGE patterns confirmed marked differences between the litter samples and the agricultural sample. The litter samples had a smaller number of distinct bands, suggesting several dominant populations, whereas the agricultural soil shows a much higher diversity without the presence of dominant bands. This is consistent with results from culturable techniques where counts of cultivatable bacteria were lower from the soybean field site but the diversity of colony morphologies was much greater. The stable DGGE pattern in samples from each stage of the process suggests that there are no major changes in the microbial composition during the composting process. 16S rRNA gene community analysis data were consistent with the stable community shown by the DGGE. Libraries from both the fresh litter and the pellet product were dominated by high-G+C gram-positive bacterial sequences and low-G+C gram-positive bacterial sequences. Previous studies of the microbial communities of chicken litter (13) have shown similar dominance of these organisms. A recent study of the microbial diversity of the intestinal bacterial community of broiler chickens (14) showed that sequences derived from the genus Clostridium dominated the community of the cecal samples. It was suggested that the differences between microbial communities at these points were due to the composting processes of the litter in the flock house. In this study few sequences with homology to Clostridium spp. were detected in the fresh samples and in the final pellet product. The 16S rRNA gene DGGE analysis and the community analysis are both based on DNA from the total bacterial community that will include sequences from nonviable or dead organisms. The study of culturable bacteria suggests that the viability of organisms in the litter is decreasing through the process although molecular methods show no changes in general microbial community structure.

The odor profile from the fresh litter was complex, and “off” odors from sulfurous compounds could be identified. Enzymatic deodorizer treatment greatly reduced odors from the litter, but it is not yet known whether this odor reduction is economically viable in a scaled-up processing plant. Current costs for the wastewater deodorizer would add approximately a dollar per ton of treated litter. The successful odor modification of chicken litter achieved by treatment with the enzymatic deodorizer suggests that this approach may enhance the process and improve the final product.

Two culturable isolates from the agricultural site were tested for odor production. Streptomyces sp. strains SOY1 and SOY3 were isolated from an agricultural site and chosen for further testing because of their desirable earthy odor. Streptomyces sp. strains SOY1 and SOY3 produced 2-methylisoborneol and geosmin, respectively. Small-scale augmentations using spores from strains SOY1 and SOY3 showed that the addition of spores to dry litter had little effect on odor. This is most likely due to the presence of insufficient moisture for the spores to germinate. Addition of water to litter samples which had been incubated with dry spores for 6 weeks resulted in a distinct earthy odor after approximately 1 week. Addition of water to these samples had presumably prompted the germination and growth of these strains and production of geosmin and methylisoborneol. The failure to detect peaks corresponding to geosmin or methylisoborneol in these earthy-smelling augmented samples could be due to several factors. The litter matrix has a substantial suppression effect on the detection of geosmin as seen with addition of 10 ppm to fresh litter and processed litter. Another possibility is that compounds produced by pure isolates SOY1 and SOY3 are modified or altered when mixed with the microbial community of the litter sample, changing the chemical structure but still generating a detectable earthy odor.

Addition of spores to the litter before it is made into pellets would result in germination of spores on addition of water. This may occur on storage under damp conditions in warehouses or retail outlets or on final application of the product to lawns. After spore germination, earthy odors produced by the Streptomyces sp., rather than presumably more offensive odors, would be perceived by the consumer. By modifying the chicken litter processing to include both enzymatic treatment and Streptomyces sp. spore addition, maximum benefit should be achieved, but a cost-benefit analysis of this combination treatment has not been performed. This would allow the marketing of the fertilizer to public parks, golf courses, and urban areas where odor is an important issue. The overall effect is conversion of a waste product with negative environmental effects into a high-value, pleasantly smelling fertilizer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennie Hunter-Cevera and Joseph Kock for helpful discussions.

Perdue AgriRecycle LLC and the Maryland Industrial Partnerships are thanked for financial support.

Footnotes

Contribution no. 05-134 from the Center of Marine Biotechnology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beach, J. R., J. Raven, C. Ingram, M. Bailey, and D. Johns. 1997. The effects on asthmatics of exposure to a conventional water-based and a volatile organic compound-free paint. Eur. Respir. J. 10:563-566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun, J. 1995. Computer-assisted classification and identification of actinomycetes. Ph.D. thesis. University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom.

- 4.Coates, J. D., K. A. Cole, U. Michaelidou, J. Patrick, M. J. McInerney, and L. A. Achenbach. 2005. Biological control of hog waste odor through stimulated microbial Fe(III) reduction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4728-4735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Felsenstein, J. 2004. PHYLIP (Phylogenetic Inference Package). Version 3.6. Department of Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle.

- 6.Fitch, W. M., and E. Margoliash. 1967. Construction of phylogenetic trees: a method based on mutation distances as estimated from cytochrome c sequences is of general applicability. Science 155:279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerber, N. N., and H. A. Lechevalier. 1965. Geosmin, an earthy-smelling substance isolated from actinomycetes. Appl. Microbiol. 13:935-938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giddens, J., and A. P. Barnett. 1980. Soil loss and microbiological quality of runoff from land treated with poultry litter. J. Environ. Qual. 9:518-520. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jukes, T. H., and C. R. Cantor. 1969. Evolution of protein molecules, p. 21-132. In H. N. Munro (ed.), Mammalian protein metabolism. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 10.Kluge, A. G., and F. S. Farris. 1969. Quantitative phyletics and the evolution of anurans. Syst. Zool. 18:1-32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane, D. J. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p. 115-175. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. J. Wiley and Sons Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 12.Loehr, R. C. 1968. Pollution implications of animal wastes—a forward orientated review. EPA 13040-07/68. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C.

- 13.Lu, J., S. Sanchez. C. Hofacre, J. J. Maurer, B. G. Harmon, and M. D. Lee. 2003. Evaluation of broiler litter with reference to the microbial composition as assessed by using 16S rRNA and functional gene markers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:901-908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu, J., U. Idris, B. Harmon, C. Hofacre, J. J. Maurer, and M. D. Lee. 2003. Diversity and succession of the intestinal bacterial community of the maturing broiler chicken. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6816-6824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maidak, B. L., J. R. Cole, C. T. Parker, Jr., G. M. Garrity, N. Larsen, B. Li, T. G. Lilburn, M. J. McCaughey, G. J. Olsen, R. Overbeek, S. Pramanik, T. M. Schmidt, J. M. Tiedje, and C. R. Woese. 1999. A new version of the RDP (Ribosomal Database Project). Nucleic Acids Res. 27:171-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin, S. A., and M. A. McCann. 1998. Microbiological survey of Georgia poultry litter. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 7:90-98. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muyzer, G., E. C. De Waal, and A. G. Uitterlinden. 1993. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:695-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nodar, R., M. J. Acea, and T. Carballas. 1990. Microbial composition of poultry excreta. Biol. Wastes 33:95-105. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nodar, R., M. J. Acea, and T. Carballas. 1990. Microbial populations of poultry pine-sawdust litter. Biol. Wastes 33:295-306. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen, A., J. S. Andersen, T. Kaewmak, T. Somsiri, and A. Dalsgaard. 2002. Impact of integrated fish farming on antimicrobial resistance in a pond environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6036-6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiffman, S. S., J. M. Walker, P. Dalton, T. S. Lorig, J. H. Reymer, D. Shusterman, and C. M. Williams. 2000. Potential health effects of odor from animal operations, wastewater treatment, and recycling of byproducts. J. Agromed. 7:7-81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry. 1997. Animal waste pollution in America: an emerging national problem. Environmental risks of live-stock and poultry production. Report compiled by the minority staff for Senator Tom Harkin, 105th Congress, First Session, Washington, D.C.

- 24.Williams, C. M., J. C. Barker, and J. T. Sims. 1999. Management and utilization of poultry wastes. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 162:105-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]