Abstract

A time series phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) 13C-labeling study was undertaken to determine methanotrophic taxon, calculate methanotrophic biomass, and assess carbon recycling in an upland brown earth soil from Bronydd Mawr (Wales, United Kingdom). Laboratory incubations of soils were performed at ambient CH4 concentrations using synthetic air containing 2 parts per million of volume of 13CH4. Flowthrough chambers maintained a stable CH4 concentration throughout the 11-week incubation. Soils were analyzed at weekly intervals by gas chromatography (GC), GC-mass spectrometry, and GC-combustion-isotope ratio mass spectrometry to identify and quantify individual PLFAs and trace the incorporation of 13C label into the microbial biomass. Incorporation of the 13C label was seen throughout the experiment, with the rate of incorporation decreasing after 9 weeks. The δ13C values of individual PLFAs showed that 13C label was incorporated into different components to various extents and at various rates, reflecting the diversity of PLFA sources. Quantitative assessments of 13C-labeled PLFAs showed that the methanotrophic population was of constant structure throughout the experiment. The dominant 13C-labeled PLFA was 18:1ω7c, with 16:1ω5 present at lower abundance, suggesting the presence of novel type II methanotrophs. The biomass of methane-oxidizing bacteria at optimum labeling was estimated to be about 7.2 × 106 cells g−1 of soil (dry weight). While recycling of 13C label from the methanotrophic biomass must occur, it is a slower process than initial 13CH4 incorporation, with only about 5 to 10% of 13C-labeled PLFAs reflecting this process. Thus, 13C-labeled PLFA distributions determined at any time point during 13CH4 incubation can be used for chemotaxonomic assessments, although extended incubations are required to achieve optimum 13C labeling for methanotrophic biomass determinations.

Increases in anthropogenic CH4 emissions have resulted in an increase in the atmospheric methane concentration from ∼0.75 to ∼1.8 parts per million of volume (ppmv) in the past 200 years (5, 33). The major terrestrial CH4 sink is the aerobic oxidation of methane by soil microorganisms, which accounts for approximately 5% of the total sink or 30 Tg year−1 (21). However, there is a high degree of uncertainty in this value, with estimates ranging from 15 to 45 Tg year−1 (39).

The activity of soil methanotrophic biomass has primarily been assessed indirectly due to the unculturable nature of high-affinity methanotrophs (11, 16). Determinations of the methane oxidation potential of different soils have shown how this activity varies with changing environmental influences, such as temperature and moisture (3, 38), soil type (6, 35), and land use (20, 27).

New techniques have recently emerged to study bacteria in situ without the need for laboratory cultures to be established. These include gene probe-based methods, such as fluorescent in situ hybridization and PCR targeting pmoA, mmoX, mxaF, and nifH (25), with a significant development being stable isotope probing (SIP) (19, 24, 26, 29). In SIP, DNA and RNA are used as specific bacterial indicators, but quantitative assessments of specific microbial groups are not straightforward in complex environments such as soils.

An alternative molecular approach to the study of high-affinity methanotrophs is to incubate soils with isotopically labeled methane and then assess the activities of methanotrophs through the determination of membrane lipids. Studies have demonstrated uptake of 14C-radiolabeled methane into different fractions of bacterial biomass and phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) (17, 30, 31), and 13C stable isotope-tracer studies have been conducted using gas chromatography/combustion/isotope ratio mass spectrometry (GC-C-IRMS), which allows precise δ13C values to be determined on individual membrane lipid components at high sensitivities (7, 10). The majority of 13C-PLFA labeling studies of methanotrophic bacteria have involved incubating soil with 13CH4 in sealed containers (static flux), with the addition of more 13CH4 at intervals to restore the initial headspace concentration. At the end of the incubation period, soils are analyzed for 13C-PLFAs (or other membrane lipids) of methanotrophic origin using GC-C-IRMS (7, 10, 12, 22). A shortcoming of using static flux chambers is the difficulty of maintaining constant methane concentrations throughout the experiment; high variability of the CH4 concentration is undesirable for quantitative studies since this may lead to instability in the methanotrophic community.

In this study a flowthrough incubation chamber was used that allowed long-term atmospheric concentration (2 ppmv) 13CH4 incubations of soils in order to derive a stable, fully 13C-labeled methanotrophic population. This enabled the biomass of the active methanotrophic community to be determined via quantification of the 13C-labeled PLFAs over a time course.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Field site.

Soils used in this investigation were sampled from the Institute of Grassland and Environmental Research upland research station at Bronydd Mawr (Wales, United Kingdom). The site was part of a low-input farming study and had received no human interference for 13 years. The grassland plot was unfertilized and ungrazed and displayed extensive vegetation growth. Because the site is an upland grassland, the soil profile was relatively shallow and had been previously characterized by the soil survey of Great Britain (32). The soil is classified as a well-drained brown earth, and with bedrock 80 cm from the ground surface, it is a fine loamy soil falling under the international soil taxonomy class of an Entisol.

Soil sampling and incubation.

Soil cores were collected to a depth of 35 cm from duplicate plots. All soil samples were stored in jars at 4°C until analysis. Prior to analysis soils were sieved (2 mm) to achieve homogeneity and remove any large stones. Soils for methane oxidation rate analysis were weighed (10 g) into serum bottles (120 ml), sealed with butyl rubber septa, and stored at 20°C for 24 h in an incubator. Headspace CH4 concentrations were then monitored over a 5-h period by GC, and methane oxidation rates were calculated by linear regression analysis. All serum bottles were slightly overpressurized to prevent external gas from leaking into the bottle, and any pressure changes were factored into CH4 uptake calculations.

Soil from a depth of 5 cm was selected for the 13CH4 incubation due to its high methane oxidation rate (0.04 nM CH4 g−1 dry weight [dwt] of soil, h−1). Soil samples for 13CH4 incubation were weighed (10 g) into 5-cm-diameter petri dishes and placed into an incubation chamber (63 liters; Perspex) sealed at the base via immersion in a water-filled tray to prevent gas leakage. The water in the base of the chamber maintained atmospheric moisture saturation and prevented samples from drying. Double-distilled water was added periodically (at ca. 2-week intervals) to the soils during incubation to maintain moisture levels. 13CH4 (2 ppmv) premixed in synthetic air was passed through the chamber at a rate of 44 ml min−1 in order to renew the headspace every 24 h. Each soil sample was incubated in triplicate with incubation times ranging from 2 to 11 weeks. A second, identical set of “control” soils was incubated in a separate building under ambient CH4 (2 ppmv) levels. All incubations were carried out in temperature-controlled rooms at 20°C. Throughout the experiment selected soil samples were removed for isotope analysis and monitored by GC headspace analysis to verify that methane oxidation activity was being maintained.

PLFA analysis.

Following incubation, all soil samples were freeze-dried, homogenized by grinding, and extracted using a modified Bligh-Dyer monophase solvent system (4). Briefly, soil (2 g dwt) was extracted using Bligh-Dyer solvent containing water buffer (0.05 M KH2PO4; pH 7.2)-chloroform-methanol in a ratio of 4:5:10 (vol/vol/vol). After the addition of solvent (3 ml), the mixture was sonicated (15 min) and centrifuged (at 3,200 rpm for 5 min). The supernatant was decanted, and the residue was extracted as above (three times). The extracts were combined and evaporated under nitrogen to yield the total lipid extract. The total lipid extract was separated into three fractions based on polarity using a 3-ml STRATA aminopropyl-bonded silica cartridge (Phenomenex). Fractions were eluted sequentially with 2:1 (vol/vol) dichloromethane-isopropanol (8 ml; yielding neutrals), 2% acetic acid in diethyl ether (12 ml; free fatty acids), and methanol (8 ml; polar fraction including phospholipids). The PLFA components of the polar fraction were released by saponification (1 ml of 0.5 M methanolic NaOH for 1 h at 80°C), and an internal standard was added (10 μl of 0.1 mg ml−1 solution of C19 n-alkane in hexane). The PLFAs were then methylated using a 14% (vol/vol) BF3-methanol solution (100 μl; Aldrich, United Kingdom) (1 h at 80°C) and extracted with chloroform (three samples of 2 ml each). The phospholipid ester-linked fatty acid methyl esters (PLFAMEs) were dissolved in hexane for analysis by GC, GC-MS, and GC-C-IRMS.

Dimethyl disulfide derivatives of monounsaturated fatty acids were prepared to facilitate determination of double-bond positions and geometries in monounsaturated fatty acids. A 100-μl aliquot of the methyl esters in dichloromethane was added to 0.25 M I2/diethyl ether (100 μl) and dimethyl disulfide (1 ml) and then heated (at 60°C for 24 h in the dark). Excess I2 was removed by addition of aqueous Na2S2O3 (5%; 2 ml), and the dimethyl disulfide derivatives were extracted with hexane (two times; 2 ml).

Instrumental analysis. (i) GC.

Gas samples from the methane oxidation rate experiments were analyzed isothermally using a Carlo Erba 5300 series GC containing a packed column (Porapak Q; 3 mm by 3 m) at 35°C. Sample introduction was via a 50-μl sample loop, and detection was performed with a flame ionization detector operating with ultrapure air (BOC specialty gases) to minimize baseline fluctuations.

PLFAs were analyzed on a Carlo Erba 5300 series GC. Sample introduction was via an on-column injector, and the detector was a flame ionization detector. FAME separation was achieved using a Varian Factor Four VF23MS column (60 m by 0.32 μm [internal diameter]; 0.15-μm film thickness). The carrier gas was hydrogen, and the oven temperature was programmed from 50°C (held for 2 min) to 100°C at 15°C min−1, from 100 to 220°C at 4°C min−1, from 220 to 240°C (held for 5 min) at 15°C min−1.

(ii) GC-MS.

GC-MS analyses were conducted using a Thermofinnigan Trace GC-MS system. The column and temperature program details were the same as those described in the above section. The ion source and the transfer line were maintained at 200 and 260°C, respectively.

(iii) GC-C-IRMS.

GC-C-IRMS analyses of PLFAMEs were carried out using a Thermofinnigan Delta PlusXL IRMS (electron ionization, 100-eV electron voltage and 1-mA electron energy; three faraday cup collectors for m/z 44, 45, and 46) instrument linked to a Hewlett Packard 6890N GC via a Thermofinnigan version 3 combustion interface with a copper oxide and platinum catalyst maintained at 850°C. Water removal was via a Nafion membrane, and the column and temperature program details were the same as those detailed in the above section but with helium as the carrier gas. Reference CO2 of known isotopic composition was used for sample calibration and introduced directly into the source three times at the start and end of each run. Each sample was run in duplicate to ensure reliable mean δ13C values.

Isotopic mass balancing.

All δ13C values were corrected for derivatization using a mass balance equation (equation 1). The δ13C value of the BF3-methanol was −41.1 ± 0.1‰, determined by bulk IRMS.

|

(1) |

where n is the number of carbon atoms, c is the compound of interest, d is the derivatizing agent, and cd is the derivatized compound of interest. The fractional abundance (F) of 13C in the control (Fc) and enriched (Fe) PLFAs was used to calculate the concentration of 13C incorporated into PLFAs from the total PLFA concentration (equation 2).

|

(2) |

The fractional abundance expresses the amount of 13C as a proportion of the total amount of carbon in the PLFA (equation 3).

|

(3) |

Statistical analysis.

Bacterial populations were compared by cluster analysis using SYSTAT, version 7.0. The distribution of PLFAs was used as a measure of similarity or distance. The analysis was performed on Euclidean distances between standardized data using averages.

RESULTS

PLFA profiles.

Table 1 shows the concentrations of the major PLFAs extracted from the Bronydd Mawr soil following incubation of 2 to 11 weeks. Microbial PLFAs are present ranging predominantly from C16 to C18 with the most abundant being 16:0, 18:1ω7c, and 18:1ω9c, but without incubation with 13CH4 and compound-specific stable carbon isotope analysis, it is not possible to determine which PLFAs derive from methanotrophs. During the course of the incubation experiment, the concentrations of the PLFAs increased. After 2 weeks of incubation the most abundant PLFA, 18:1ω7c, displayed a concentration of 51.1 nM g−1 (dwt) of soil, increasing to 182.5 nM g−1 (dwt) of soil after 11 weeks.

TABLE 1.

Concentration of major PLFAs extracted from Bronydd Mawr soil at a depth of 5 cm

| PLFA | Concn (nM/g [dwt] of soil) after incubation for (weeks):

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| C19 stda | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| i15:0 | 13.4 | 13.2 | 11.8 | 23.1 | 16.9 | 22.3 | 26.2 | 39.7 | 27.0 | 29.9 |

| a15:0 | 15.1 | 14.0 | 12.6 | 26.5 | 17.0 | 24.4 | 26.7 | 39.9 | 28.0 | 30.0 |

| i16:0 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 9.6 | 6.6 | 7.4 |

| 16:0 | 39.8 | 26.3 | 23.6 | 38.3 | 41.8 | 58.2 | 66.2 | 90.7 | 66.6 | 81.2 |

| 16:1ω11 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 10.3 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 10.5 | 10.6 |

| 16:1ω9 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 4.8 | 6.9 | 8.0 | 10.3 | 6.9 | 7.7 |

| br17:0 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 14.8 | 15.8 | 14.5 | 22.9 | 29.3 | 42.2 | 27.4 | 32.8 |

| 16:1ω7 | 11.8 | 10.7 | 12.9 | 16.8 | 15.4 | 24.3 | 31.0 | 44.7 | 29.1 | 34.7 |

| i17:0 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 7.2 | 8.3 | 6.9 | 11.9 | 15.2 | 21.0 | 13.1 | 16.4 |

| 16:1ω5 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 7.7 | 8.8 | 7.3 | 12.6 | 16.1 | 22.3 | 13.9 | 17.4 |

| a17:0 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 6.3 | 7.6 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 14.2 | 8.8 | 11.6 |

| 17:1ω8 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 6.4 | 8.5 | 7.3 | 12.4 | 11.1 | 14.5 | 9.0 | 13.2 |

| 18:0 | 13.4 | 6.8 | 9.0 | 9.6 | 11.0 | 17.2 | 16.9 | 21.6 | 15.7 | 22.4 |

| 19:1 | 14.9 | 12.1 | 14.0 | 15.5 | 18.9 | 30.3 | 32.9 | 36.7 | 26.9 | 33.0 |

| 18:1ω9c | 32.0 | 25.6 | 36.5 | 39.4 | 46.0 | 76.9 | 94.7 | 127.2 | 88.7 | 116.3 |

| 18:1ω7c | 51.1 | 42.6 | 59.4 | 53.1 | 67.4 | 112.6 | 145.8 | 199.0 | 150.7 | 182.5 |

| 18:1ω5c | 5.8 | 5.2 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 12.2 | 16.0 | 21.5 | 14.5 | 18.4 |

| 18:2 | 11.7 | 11.6 | 15.0 | 21.2 | 14.3 | 28.3 | 23.6 | 26.1 | 17.1 | 27.8 |

Internal standard (std).

13CH4 labeling technique.

The clearest way to display changes in compound-specific carbon isotope values is as Δ13C values (δ13Clabeled − δ13Ccontrol) (Fig. 1). It can be seen that there is a marked and steady incorporation of 13C label into selected PLFAs with time: 16:1ω5 and 18:ω7c show the largest increase in Δ13C values, rising by 50.0‰ and 38.4‰, respectively, after 11 weeks; i17:0 and 18:1ω5c displayed the next largest increases in Δ13C values of 15.1‰ and 9.8‰, respectively. Standard deviations are relatively low (16:1ω5 excluded) for such a complex biological system. 13C label incorporation was slow compared to other studies that have used higher concentrations of CH4 (12), reaching a maximum Δ13C value of 50‰ after 11 weeks.

FIG. 1.

Δ13C values of selected PLFAs incorporating 13C label following incubation with 2 ppmv of 13CH4. The division into graphs A and B enables the PLFAs incorporating lower proportions of 13C label to be seen more clearly. Error bars represent ±1 standard deviation.

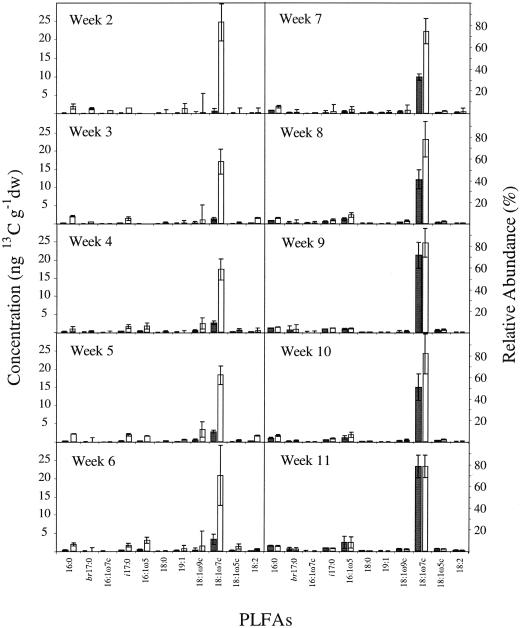

Figure 2 compares the concentrations of PLFAs incorporating the 13C label throughout the study and indicates that 13C-labeled PLFA concentrations increase with time. Converting δ13C values to absolute concentrations of 13C-PLFA (7) provides a true representation of the methanotrophic community PLFA distribution, indicating 18:1ω7c to be the dominant PLFA. Figure 2 also shows the relative abundance of 13C-labeled PLFAs for each time point. Within experimental error, the composition of the methanotrophic community, as judged by the constancy of the 13C-PLFA distribution, was maintained throughout the experiment.

FIG. 2.

Total concentration of 13C label incorporated into each PLFA in ng of 13C g−1 (dwt) of soil (black bars) following incubation with 2 ppmv of 13CH4 and relative mole percentage abundance (white bars) for the main 13C-labeled PLFAs from 2 to 11 weeks following incubation with 2 ppmv of 13CH4. PLFA analyses were performed on soil samples taken at weekly intervals, and only PLFAs with a relative abundance of >3% are presented. Error bars represent ±1 standard deviation.

Taxonomic identity of high-affinity methane-oxidizing bacteria.

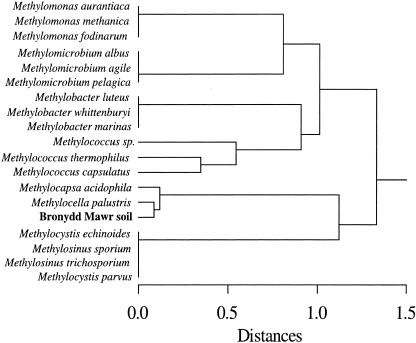

The 13C-labeling study shows that several PLFAs are directly derived from high-affinity methane-oxidizing bacteria. A comparison of the 13C-labeled PLFA distribution extracted from the Bronydd Mawr soil with published PLFA compositions of pure cultures of methanotrophic bacteria (9, 14) is shown in Fig. 3. The cluster analysis indicates that the bacteria mediating CH4 oxidation are most closely related to Methylocella palustris (8). The PLFA profiles of the methanotrophs from the Bronydd Mawr soil and M. palustris are both dominated by 18:1ω7c.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the 13C-labeled PLFA distribution extracted from the Bronydd Mawr soil following incubation with 2 ppmv of 13CH4 with published PLFA compositions of pure cultures of methanotrophic bacteria (9, 14). PLFA compositions used were the mole percentages of the PLFAs of pure cultures and the labeled PLFAs extracted from the soil. A hierarchical tree was produced by cluster analysis performed with the software package SYSTAT, version 7, on Euclidean distances between the standardized data using averages.

Quantification of high-affinity methane-oxidizing bacteria.

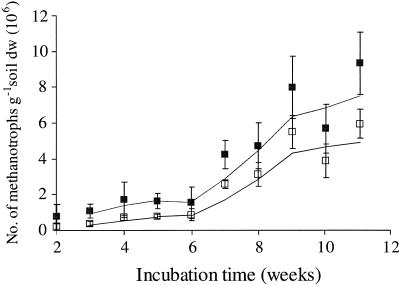

By determining the total amount of 13C incorporated into the bacterial PLFAs, it is possible to estimate the methanotrophic biomass. Frostegård and Bååth (15) calculated an average value of 1.4 × 10−17 mol of bacterial PLFA cell−1. Using this value an estimate of methanotrophic biomass of 5.6 × 106 to 8.8 × 106 methanotrophic cell g−1 (dwt) of soil was obtained. The range of this estimate takes into account experimental errors. Moreover, the upper and lower limits are also dependent on the concentration of 13C-labeled PLFAs resulting from recycling of the 13C label into the total bacterial biomass. The upper limit of the estimate of 8.8 × 106 methanotrophic cells g−1(dwt) of soil is calculated from all PLFAs that incorporated 13C label (including those not known to be produced by culturable methanotrophs) and, hence, may be a slight overestimate as a result of 13C label recycling. In contrast, the estimate of 5.6 × 106 methanotrophic cells g−1 (dwt) of soil is based on only the major 13C-labeled methanotrophic PLFA, namely 18:1ω7c.

Figure 4 plots estimated 13C-labeled methanotroph cell numbers at each time point throughout the incubation. Incorporation of 13C label was slow initially but increased rapidly between 6 and 9 weeks, before slowing during weeks 9 and 10. The curves derived from both 13C-labeled 18:1ω7c and total bacterial 13C-labeled PLFAs appeared to plateau at 10 to 11 weeks. This indicates that the microbial population was at or close to a steady state, with the majority of methanotrophic bacteria having incorporated the 13C label.

FIG. 4.

Increase in number of 13C-labeled methanotrophic bacterial cells throughout the 13CH4 incubation. The plot of 18:1ω7c (open squares) represents the main labeled PLFA and is unlikely to include recycled 13C, whereas the plot of all 13C-labeled PLFAs (filled squares) may include up to ca. 10% recycled 13C label. Error bars represent ±1 standard deviation. Trend lines indicate the moving average of two data points.

DISCUSSION

13CH4 labeling technique.

The flowthrough incubation system employed in this investigation is clearly an advantage over the static flux chambers used in previous 13C-labeling studies of high-affinity methanotrophs (7, 10, 12, 22). The degree of 13C label incorporation was relatively low, which reduces problems with 13C “carryover effects” into closely eluting PLFAs. Mottram and Evershed (28) observed that 13C-enriched FAMEs possessing δ13C values of ∼500‰ created a significant within-run carryover effect into unlabeled FAMEs eluting immediately after 13C-enriched components. While not a significant problem in qualitative 13C-labeling studies, this effect may introduce significant errors in quantitative studies involving 13C labeling.

A second advantage of low 13C labeling is the ability to assess incorporation at a 13CH4 concentration close to the ambient atmospheric methane concentration. This is considerably more representative of a natural soil system than the 10- to 50-ppmv concentrations typically used in static chamber incubations (7, 12, 22) and the elevated concentrations utilized in DNA-based SIP studies (19, 24, 29). Radajewski et al. (29) estimated that gravimetrically separated 13C-DNA fractions contained 65 to 100% 13C. To achieve this magnitude of 13C label incorporation, artificially high 13CH4 concentrations are applied, with most studies utilizing 13CH4 concentrations above 1% (vol/vol). RNA-based SIP is more sensitive than DNA-based SIP and could potentially characterize active high-affinity methanotrophs following incubations at ambient 13CH4 concentrations, if limitations associated with extracting RNA from environmental samples can be overcome (25).

In this experiment the maximum incubation time was 11 weeks, which is a substantially longer incubation period than has been used in other investigations (7, 10, 12, 22); the results obtained indicate that even after this period of time the microbial population remains fully active in oxidizing methane. After 9 weeks of incubation, it would appear that the high-affinity methanotroph community has reached a steady state in terms of growth and 13C turnover, suggesting that methanotrophic population estimates made at that point are representative of the active methanotrophic bacteria in the system.

Although the incubation period was longer than that used in previous studies (7, 10, 12, 22), it appeared that recycling of 13C label among other microorganisms was negligible. One of the main aims of this study was to monitor the incorporation of 13CH4 over time to investigate whether any significant turnover of the 13C label into nonmethanotrophic PLFAs occurred. If PLFAs initially show no 13C label incorporation but then incorporate 13C label after an extended period of incubation, it is likely that the microbes from which they derive are not obtaining carbon for biosynthesis directly from CH4 but through utilization of other substrates containing 13C label. Figure 2 indicates that, within experimental error, the 13C-labeled PLFA distribution remains consistent throughout the incubation period, thereby excluding the possibility of a significant proportion of 13C-labeled PLFAs resulting from recycling of the 13C label within the wider microbial biomass. Considerable care was taken when designing the 13CH4 flowthrough incubation system to introduce low concentrations of 13CH4 to the system and extract all respired gases (including 13CO2), thereby limiting any 13C-labeled PLFAs derived through 13CO2 utilization by chemoautotrophic bacterial communities. Moreover, controlling the concentrations of 13CH4 at 2 ppmv, i.e., close to the atmospheric concentration, ensured that only high-affinity methanotrophs would be active, thus minimizing the production of unnaturally high concentrations of 13C-labeled metabolites or bacterial necromass.

Quantification of methanotrophic bacterial biomass.

By employing the PLFA concentration per bacterial cell derived by Frostegård and Bååth (15), we estimated the population of methanotrophic bacteria at ca. 7.2 × 106 cells g−1 (dwt) of soil (range, 5.6 × 106 to 8.8 × 106 cells g−1). Incorporation of the 13C label had slowed toward the end of the 11-week incubation, indicating that the microbial biomass had reached, or was close to, a steady state. When considering this methanotrophic biomass estimate, it is important to note that the conversion factor used in the calculation is based on a mean PLFA concentration for a wide range of bacteria (15). We are currently improving this estimate by deriving a specific PLFA concentration for methanotrophic bacteria.

Few studies have made an assessment of methanotrophic biomass in terrestrial environments. Bender and Conrad (1, 2) used a direct most probable number technique to count methanotrophic bacteria from a wide range of different environments. The technique works well at high CH4 concentrations but is unsuitable for enumerating high-affinity methanotrophs that oxidize CH4 at ambient concentrations. Horz et al. (18) also used a most probable number technique to quantify the methane-oxidizing bacteria in a German wet meadow soil and estimated the most abundant methanotroph at 105 to 107 cells g−1 (dwt) of soil. Kolb et al. (23) utilized quantitative PCR to calculate the biomass of methanotrophic bacteria in acidic and neutral forest soils. They detected both culturable and nonculturable methanotrophs in forest soils in the range of 106 gene copies g−1 (dwt) of soil. The number of cells is lower than this as at least two pmoA gene copies can be expected per cell (34), and unrepresentative discrepancies can be exaggerated by bias introduced during PCR amplification (37). Sundh et al. (36) estimated the cell numbers of methanotrophic bacteria in boreal peatlands by focusing on two specific PLFAs believed to be unique to methanotrophic bacteria, namely 16:1ω8 and 18:1ω8; the total number of methanotrophic bacteria estimated ranged from 0.3 × 106 to 51 × 106 cells g−1 of wet peat (36), although it is unknown whether methanotrophic bacteria are the only bacteria that exclusively produce ω8 monounsaturated PLFAs.

Our estimate of methanotrophic biomass appears low compared to the total bacterial biomass of 5 × 1010 cells, but it is reasonable when considering the widely differing concentrations of substrates available to the total soil microbial community compared to the concentration of CH4 available to the methanotrophic bacteria. Roslev et al. (30) calculated theoretical microbial biomass production with CH4 as the sole carbon source and determined that the potential for population growth solely utilizing atmospheric methane is limited. They estimated a production of ca. 8 × 106 bacteria cm−3 day−1. The number of methanotrophic bacteria calculated in the present study is somewhat lower than their estimated daily production value, but CH4 is a minimal carbon source in aerobic mineral soils, and there are many other more extensively bioavailable carbon substrates.

The 13C-labeled PLFA distribution obtained herein for the high-affinity methane-oxidizing bacteria present in the Bronydd Mawr soils shows that they are similar to known type II methanotrophs, agreeing with our previous studies of a range of northern European soils (10, 12). The PLFA distribution obtained in this study, particularly the high abundance of 18:1ω7c, indicates that the Bronydd Mawr methanotrophs are a novel species closely related to M. palustris (Fig. 3) (9). PmoA gene data for the active methanotrophic bacteria in the Bronydd Mawr soil would improve the accuracy of this taxonomic assignment, but this was not the primary aim of this investigation. Overall, indications are that although there are similarities in the high-affinity methanotrophic populations active in soils, there are also some differences between the populations operating in different environments. Other studies have shown that high-affinity methanotrophs are often closely related to known type II low-affinity methanotrophs (10, 12), which could be due to the low-substrate conditions that high-affinity methanotrophs tolerate with very low CH4 concentrations. Type II methanotrophs have been found in environments that are more nutrient limited than those typically inhabited by type I methanotrophs, such as oxygen-poor layers of landfill-cover soils (13).

Conclusions.

We have demonstrated herein a new flowthrough 13C-labeling approach which allows the simultaneous determination of both methanotrophic biomass and taxon using PLFA 13C labeling. It has been shown that an Alphaproteobacteria-specific PLFA (18:1ω7c) incorporated 13C label over a period of 11 weeks. We have determined the active high-affinity methanotrophic biomass based on concentrations of 13C-labeled PLFAs and shown that there is no substantial turnover or incorporation of the 13C label into nonmethanotrophic PLFAs.

Acknowledgments

We thank I. D. Bull and R. Berstan for technical assistance. We are grateful for the use of the NERC Life Sciences Mass Spectrometry Facility, and we thank the Institute of Grassland and Environmental Research for field site access at Bronydd Mawr.

The research facility used in this study at the Bristol Biogeochemistry Research Centre was funded in part from a recent major infrastructure grant provided by the United Kingdom Joint Higher Education Funding Council for England and Office of Science and Technology Science Research Investment Fund and by the University of Bristol. This work was partially supported by a Royal Society grant (574006.G503/24026/SM) to E.R.C.H. This investigation was performed while P.J.M. was in receipt of an NERC studentship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bender, M., and R. Conrad. 1992. Kinetics of CH4 oxidation in oxic soils exposed to ambient air or high CH4 mixing ratios. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 101:261-270. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bender, M., and R. Conrad. 1994. Methane oxidation activity in various soils and fresh-water sediments—occurrence, characteristics, vertical profiles, and distribution on grain-size fractions. J. Geophys. Res. 99:16531-16540. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billings, S. A., D. D. Richter, and J. Yarrie. 2000. Sensitivity of soil methane fluxes to reduced precipitation in boreal forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 32:1431-1441. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bligh, E. G., and W. J. Dyer. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37:911-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blunier, T., J. A. Chappellaz, J. Schwander, J. M. Barnola, T. Desperts, B. Stauffer, and D. Raynaud. 1993. Atmospheric methane, record from a Greenland ice core over the last 1000 years. Geophys. Res. Lett. 20:2219-2222. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boeckx, P., O. VanCleemput, and I. Villaralvo. 1997. Methane oxidation in soils with different textures and land use. Nutr. Cycle Agroecosyst. 49:91-95. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boschker, H. T. S., S. C. Nold, P. Wellsbury, D. Bos, W. de Graaf, R. Pel, R. J. Parkes, and T. E. Cappenberg. 1998. Direct linking of microbial populations to specific biogeochemical processes by 13C-labelling of biomarkers. Nature 392:801-805. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman, J. P., J. H. Skerratt, P. D. Nichols, and L. I. Sly. 1991. Phospholipid fatty-acid and lipopolysaccharide fatty-acid signature lipids in methane-utilizing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 85:15-22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowman, J. P., L. I. Sly, P. D. Nichols, and A. C. Hayward. 1993. Revised taxonomy of the methanotrophs—description of Methylobacter gen. nov., emendation of Methylococcus, validation of Methylosinus and Methylocystis species, and a proposal that the family Methylococcaceae includes only the group I methanotrophs. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:735-753. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bull, I. D., N. R. Parekh, G. H. Hall, P. Ineson, and R. P. Evershed. 2000. Detection and classification of atmospheric methane oxidising bacteria in soil. Nature 405:175-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conrad, R. 1996. Soil microorganisms as controllers of atmospheric trace gases (H2, CO, CH4, OCS, N2O, and NO). Microbiol. Rev. 60:609-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crossman, Z. M., P. Ineson, and R. P. Evershed. 2005. The use of 13C-labelling of bacterial lipids in the characterisation of ambient methane-oxidising bacteria in soils. Org. Geochem. 36:769-778. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crossman, Z. M., F. Abraham, and R. P. Evershed. 2004. Stable isotope pulse-chasing and compound specific stable carbon isotope analysis of phospholipid fatty acids to assess methane oxidizing bacterial populations in landfill cover soils. Environ Sci. Technol. 38:1359-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dedysh, S. N. 2002. Methanotrophic bacteria of acidic sphagnum peat bogs. Microbiology 71:638-650. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frostegård, Å., and E. Bååth. 1996. The use of phospholipid fatty acid analysis to estimate bacterial and fungal biomass in soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 22:59-65. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson, R. S., and T. E. Hanson. 1996. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 60:439-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmes, A. J., P. Roslev, I. R. McDonald, N. Iversen, K. Henriksen, and J. C. Murrell. 1999. Characterization of methanotrophic bacterial populations in soils showing atmospheric methane uptake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3312-3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horz, H. P., A. S. Raghubanshi, E. Heyer, C. Kammann, R. Conrad, and P. F. Dunfield. 2002. Activity and community structure of methane-oxidising bacteria in a wet meadow soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 41:247-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutchens, E., S. Radajewski, M. G. Dumont, I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2004. Analysis of methanotrophic bacteria in Movile Cave by stable isotope probing. Environ. Microbiol. 6:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutsch, B. W. 1998. Tillage and land use effects on methane oxidation rates and their vertical profiles in soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 27:284-292. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalil, M. 2000. Sources of methane: an overview, p. 98-111. In M. Khalil (ed.), Atmospheric methane: its role in the global environment. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 22.Knief, C., A. Lipski, and P. F. Dunfield. 2003. Diversity and activity of methanotrophic bacteria in different upland soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6703-6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolb, S., C. Knief, P. F. Dunfield, and R. Conrad. 2005. Abundance and activity of uncultured methanotrophic bacteria involved in the consumption of atmospheric methane in two forest soils. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1150-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin, J. L., S. Radajewski, B. T. Eshinimaev, Y. A. Trotsenko, I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2000. Molecular diversity of methanotrophs in Transbaikal soda lake sediments and identification of potentially active populations by stable isotope probing. Environ. Microbiol. 6:1049-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald, I. R., S. Radajewski, and J. C. Murrell. 2005. Stable isotope probing of nucleic acids in methanotrophs and methylotrophs: a review. Org. Geochem. 36:779-787. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris, S. A., S. Radajewski, T. W. Willison, and J. C. Murrell. 2002. Identification of the functionally active methanotroph population in a peat soil microcosm by stable-isotope probing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1446-1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosier, A. R., J. A. Delgado, V. L. Cochran, D. W. Valentine, and W. J. Parton. 1997. Impact of agriculture on soil consumption of atmospheric CH4 and a comparison of CH4 and N2O flux in subarctic, temperate and tropical grasslands. Nutr. Cycle Agroecosyst. 49:71-83. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mottram, H. R., and R. P. Evershed. 2003. Practical considerations in the gas chromatography/combustion/isotope ratio monitoring mass spectrometry of 13C-enriched compounds: detection limits and carryover effects. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 17:2669-2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radajewski, S., G. Webster, D. S. Reay, S. A. Morris, P. Ineson, D. B. Nedwell, J. I. Prosser, and J. C. Murrell. 2002. Identification of active methylotroph populations in an acidic forest soil by stable isotope probing. Microbiology 148:2331-2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roslev, P., N. Iversen, and K. Henriksen. 1997. Oxidation and assimilation of atmospheric methane by soil methane oxidizers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:874-880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roslev, P., and N. Iversen. 1999. Radioactive fingerprinting of microorganisms that oxidize atmospheric methane in different soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4064-4070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudeforth, C. C., R. Hartnup, J. W. Lea, T. R. E. Thompson, and P. S. Wright. 1984. Soils and their use in Wales. Bull. 11. Soil Survey of England and Wales, Harpenden, United Kingdom.

- 33.Stauffer, B., G. Fischer, A. Neftel, and H. Oeschger. 1985. Increase of atmospheric methane recorded in Antarctic ice core. Science 229:1386-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stolyar, S., A. M. Costello, T. L. Peeples, and M. E. Lidstrom. 1999. Role of multiple gene copies in particulate methane monooxygenase activity in the methane-oxidizing bacterium Methylococcus capsulatus Bath. Microbiology 145:1235-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Striegl, R. G., T. A. McConnaughey, D. C. Thorstenson, E. P. Weeks, and J. C. Woodward. 1992. Consumption of atmospheric methane by desert soils. Nature 357:145-147. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sundh, I., P. Borga, M. Nilsson, and B. H. Svensson. 1995. Estimation of cell numbers of methanotrophic bacteria in boreal peatlands based on analysis of specific phospholipid fatty-acids. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 18:103-112. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Von Wintzingerode, F., U. B. Gobel, and E. Stackebrandt. 1997. Determination of microbial diversity in environmental samples: pitfalls of PCR-based rRNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 21:213-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whalen, S. C., and W. S. Reeburgh. 1996. Moisture and temperature sensitivity of CH4 oxidation in boreal soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 28:1271-1281. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wuebbles, D. J., and K. Hayhoe. 2002. Atmospheric methane and global change. Earth Sci. Rev. 57:177-210. [Google Scholar]