Abstract

The treatment of infections caused by bacteria resistant to the vast majority of antibiotics is a challenge worldwide. Antimicrobial peptides (APs) make up the front line of defense in those areas exposed to microorganisms, and there is intensive research to explore their use as new antibacterial agents. On the other hand, it is known that subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics affect the expression of numerous bacterial traits. In this work we evaluated whether treatment of bacteria with subinhibitory concentrations of quinolones may alter the sensitivity to APs. A 1-h treatment of Klebsiella pneumoniae with 0.25× the MIC of ciprofloxacin rendered bacteria more sensitive to polymyxins B and E, human neutrophil defensin 1, and β-defensin 1. Levofloxacin and nalidixic acid at 0.25× the MICs also increased the sensitivity of K. pneumoniae to polymyxin B, whereas gentamicin and ceftazidime at 0.25× the MICs did not have such an effect. Ciprofloxacin also increased the sensitivities of K. pneumoniae ciprofloxacin-resistant strains to polymyxin B. Two other pathogens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Haemophilus influenzae, also became more sensitive to polymyxins B and E after treatment with 0.25× the MIC of ciprofloxacin. Incubation with ciprofloxacin did not alter the expression of the K. pneumoniae loci involved in resistance to APs. A 1-N-phenyl-naphthylamine assay showed that ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin increased the permeabilities of the K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa outer membranes, while divalent cations antagonized this action. Finally, we demonstrated that ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin increased the binding of APs to the outer membrane by using dansylated polymyxin B.

The development of bacteria which have acquired resistance to the vast majority of antibiotics is one of the main problems in clinical settings. Challenged by decades of drug exposure, bacteria have evolved through adaptation and natural selection defensive mechanisms that render antimicrobials impotent. Despite the many advances in microbiology, biochemistry, and drug discovery, we are not keeping pace with the ability of bacteria to adapt to and resist antibacterials. Therefore, there is a vital need to develop new effective therapeutics.

Antimicrobial peptides (APs) are ubiquitous in nature, and in vertebrates they are the front line of defense against infections in those areas exposed to pathogens. There are four structural classes of APs: the disulfide-bonded β-sheet peptides, the amphipathic α-helical peptides, the extended peptides, and the loop-structured peptides (22, 36). Despite their diverse sizes and structures, nearly all antimicrobial peptides have a strong net cationic (positive) charge, and the three-dimensional folding results in an amphipathic structure. These features are critical for bacterial killing (5, 22, 36). The microbicidal action of APs is initiated through electrostatic interaction with the anionic bacterial surface. In the case of gram-negative bacteria, APs interact with the acidic lipid A moiety of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS). This leads to a disorganization of the outer membrane (OM) and the access of APs to the periplasm, from which they reach the inner membrane (5, 22, 36, 41). The loss of inner membrane integrity eventually leads to bacterial death, although there is an increasing body of evidence to indicate that APs may have intracellular targets (5, 22, 36).

APs have some features that make them good candidates as antimicrobial agents. They have broad spectra of activity, they kill bacteria rapidly, and when they are used at concentrations close to the MIC, bacteria do not easily develop resistance. In addition, APs can act in synergy with classical antibiotics; APs decrease the MIC of a given antibiotic. Polymyxins B and E (colistin) are two APs originally synthesized from Bacillus polymyxa and made available for clinical use in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Soon after their introduction, their clinical use was limited due to perceived toxic side effects and to the emergence of new antimicrobials (10, 23). However, the occurrence of multidrug-resistant bacteria has prompted a reconsideration of polymyxin therapies. In addition, intensive research is under way to design new APs based on natural APs without the adverse effects of polymyxins.

A promising therapeutic approach would be to exogenously apply APs alone or in combination with conventional antibiotics. This is hampered by the important lack of in vivo studies of the actions of APs. An alternative approach would be to use compounds which render bacteria susceptible to those APs naturally present at the sites of infection. This is based on the idea that compounds which destabilize the bacterial surface sensitize bacteria to agents normally excluded (41). Chelators such as EDTA or sodium hexametaphosphate are well-studied examples of such compounds (41). However, the indiscriminating chelating activity reduces the value of chelators in clinical settings.

An increasing body of evidence shows that subinhibitory concentrations of many antibiotics modulate numerous bacterial traits, e.g., the morphology of cells, the expression of OM proteins, and the production of virulence factors (4, 9, 27, 28, 40, 42). This antibiotic effect may increase the sensitivities of the microorganisms to host defense systems, thus contributing to the eradication of the infecting bacteria. All of this has been particularly studied in the case of the quinolones.

This study provides evidence that subinhibitory concentrations of quinolones increase the sensitivities of three gram-negative pathogens (Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Haemophilus influenzae) to APs. Our results also show that quinolones have a direct effect on the OM, which might explain the increased sensitivity to APs after treatment with quinolones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

K. pneumoniae 52145 is a clinical isolate (serotype O1:K2) sensitive to ampicillin and has been described previously (34). K. pneumoniae MCQ-102, MCQ-121, and MCQ-122 are clinical isolates that are resistant to quinolones and have been characterized in a recent study (31). P. aeruginosa PAO1 and H. influenzae 05-118741 were kindly provided by A. Oliver. The Klebsiella and Pseudomonas strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. H. influenzae was grown in chocolate agar plates or in tryptone soy broth (TSB) supplement with Fildes enrichment (sTSB) at 37°C in 5% CO2. When appropriate, the following antibiotics were added to the growth medium at the indicated concentrations: ampicillin (Amp), 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Clm), 25 μg/ml.

Antibiotics and antimicrobial peptides.

Ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin were provided by Aventis. Gentamicin, ceftazidime, polymyxins B and E, and human neutrophil defensin 1 (HNP-1) were purchased from Sigma. β-Defensin 1 (HBD1) was purchased from Peprotech.

Antimicrobial peptide sensitivity assay.

The bacterial strains were grown at 37°C in 5 ml of LB or sTSB, harvested (by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min at 5°C) in the exponential phase of growth, and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To test the effect of 0.25× the MICs of the antibiotics, they were added when the culture reached the exponential phase, and after 1 h of incubation, the cultures were treated exactly as described before.

A suspension containing approximately 1 × 105 CFU/ml was prepared in 10 mM PBS (pH 6.5), 1% TSB, and 100 mM NaCl. Five microliters of this suspension was mixed in Eppendorf tubes with various concentrations of antimicrobial peptides to get a final volume of 30 μl. After 1 h of incubation, the contents of the Eppendorf tubes were plated on LB agar plates in the case of the Klebsiella and Pseudomonas strains or on chocolate agar plates in the case of Haemophilus.

Colony counts were determined, and the results were expressed as the percentages of the colony counts of bacteria not exposed to antibacterial agents. The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of the antimicrobial peptides were defined as the concentrations that produced a 50% reduction in the colony counts compared with those of the bacteria not exposed to the antibacterial agents. All experiments were done with duplicate samples on three independent occasions.

Construction of luciferase reporter strains.

The firefly luciferase reporter and Pir-dependent suicide vectors were constructed as follows.

(i) cps reporter suicide vector.

The vector pEPPcpsluc has been constructed previously (6). In this plasmid the luciferase gene is under the control of the cps promoter region. This plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli S17-1λ pir, which mobilized it into K. pneumoniae 52145. A Clm-resistant transconjugant was selected. The suicide vector was integrated into the transconjugant by homologous recombination, and this was confirmed by Southern blotting (data not shown).

(ii) pagP reporter suicide vector.

A DNA fragment containing the promoter region of the pagP gene was amplified by PCR with the chromosomal DNA from strain 52145 as the template and Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs) and with primers PKpnPAgpF (5′-AGATAATGGCCGCGATGGAG-3′) and KpnPagPinvR (5′-CATTCCAGGTCTGCGCTACG-3′). The primers were designed by using the sequence from the K. pneumoniae MGH78578 unfinished genomic sequence project (htpp://pedant.gsf.de/cgi-bin/wwwfly.pl). The PCR fragment was cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen) to obtain pBLUNTPKpnPagP. The cloned fragment was sequenced to ensure that no mistakes were introduced during amplification. This plasmid was digested with EcoRI, and a 1-kb fragment containing the pagP promoter region was gel purified and cloned into the EcoRI site of the vector pGPL01 (16). This vector contains a promoterless firefly luciferase gene and an R6K origin of replication. A plasmid in which the luciferase gene was under the control of the pagP promoter was identified by restriction digestion analysis and was named pGPLPknpPagP. This plasmid was electroporated into K. pneumoniae, and an Amp-resistant strain was selected in which the suicide vector was integrated into the genome by homologous recombination. This was confirmed by Southern blotting (data not shown).

(iii) pmrHFIJKLM reporter suicide vector.

A 700-bp DNA fragment containing the promoter region of the operon was amplified by PCR with chromosomal DNA from strain 52145 as the template and Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs) and with primers PknppmrHF (5′-GGAATTCCGCGATGCCGGCCCGGCCTAC-3′; the EcoRI site is underlined) and PkpnpmrHR (5′-GGGTACCGTCGCATGACGGTTGCCGGTC-3′, the KpnI site is underlined). The primers were designed by using the sequence from the K. pneumoniae MGH78578 unfinished genomic sequence project (htpp://pedant.gsf.de/cgi-bin/wwwfly.pl). The PCR fragment was digested with EcoRI and KpnI and cloned into the EcoRI-KpnI sites of pGPL01 to obtain pGPLPKpnpmrH. The cloned fragment was sequenced to ensure that no mistakes were introduced during amplification. This plasmid was electroporated into K. pneumoniae, and an Amp-resistant strain was selected in which the suicide vector was integrated into the genome by homologous recombination. This was confirmed by Southern blotting (data not shown).

Luciferase activity.

The reporter strains were grown on an orbital incubator shaker (180 rpm) until late log phase, and the optical density at 540 nm (OD540) was recorded. A 100-μl aliquot of the bacterial suspension was transferred to an Eppendorf tube and mixed with 100 μl of luciferase assay reagent (1 mM d-luciferin [Synchem] in 100 nM citrate buffer [pH 5]). The luminescence was immediately measured with a luminometer (Hidex). The results are expressed as relative light units (RLU) per OD540. All measurements were done in triplicate on at least three separate occasions.

Outer membrane permeability to NPN.

1-N-Phenyl-naphthylamine (NPN) is an uncharged hydrophobic fluorescent probe whose quantum yield suddenly increases when it is transferred from a hydrophilic to a hydrophobic environment. When NPN is added to cells it fluoresces weakly since it is unable to breach the OM barrier, and it is also a substrate for efflux pumps. However, upon OM destabilization and in the presence of an energy inhibitor, NPN partitions into the membrane, emitting a bright fluorescence (1, 26, 41).

A suspension of exponentially growing cells (OD600, 0.5) was prepared in 2 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 5 μM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone. One milliliter of this suspension was transferred to 1-cm fluorimetric cuvettes, and NPN was added (final concentration, 10 μM). After NPN addition, the following antibiotics or CaCl2 was added at the indicated concentrations: ciprofloxacin, 0.6 μg/ml; levofloxacin, 0.6 μg/ml; and CaCl2, 10 mM. In preliminary experiments these were the minimal concentrations causing the characteristic effects in this assay (see Results). Quenching was not observed under these conditions. The fluorescence was monitored with a spectrofluorophotometer (RF-5301PC; Shimadzu), set as follows: excitation, 350 nm; emission, 420 nm; and slit width, 3 nm. The results are expressed as relative fluorescence units (RFU). Measurements were recorded as ASCII files and were exported to a personal computer for plotting. All measurements were done in duplicate on three separate occasions.

Dansyl polymyxin B binding studies.

K. pneumoniae 52145 was grown at 37°C in 5 ml of LB medium, harvested (by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min at 5°C) in the exponential phase of growth, and washed three times with PBS. To test the effects of 0.25× the MICs of ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, the antibiotics were added when the culture reached the exponential phase, and after 1 h of incubation, the culture was washed three times with PBS.

For the binding experiments, a suspension (OD600, 0.5) was prepared in 2 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and 1 ml of this suspension was transferred to 1-cm fluorimetric cuvettes. The fluorescence spectra of dansyl polymyxin B (Molecular Probes) were recorded at room temperature from 400 to 600 nm at an excitation wavelength of 320 nm with a spectrofluorophotometer (RF-5301PC; Shimadzu). The slit width was 3 nm. The results are expressed as RFU. The measurements were recorded as ASCII files and were exported to a personal computer for plotting. All measurements were done in duplicate on four separate occasions.

Statistical methods.

Comparisons among groups were made by the two-sample t test or, when the requirements were not met, by the Mann-Whitney U test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The MICs of ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and nalidixic acid for K. pneumoniae 52145 (0.05, 0.25, and 4 μg/ml, respectively) were comparable to the MICs for the other sensitive Klebsiella strains and were used to calculate the 0.25× MICs, which were used as subinhibitory concentrations. The growth rate and the bacterial numbers of strain 52145 were not affected by 0.25× the MICs of the quinolones during a 2-h exposure; microscopic examination revealed no filamentation during this incubation period. All subsequent experiments were conducted with cultures that had been treated for 1 h.

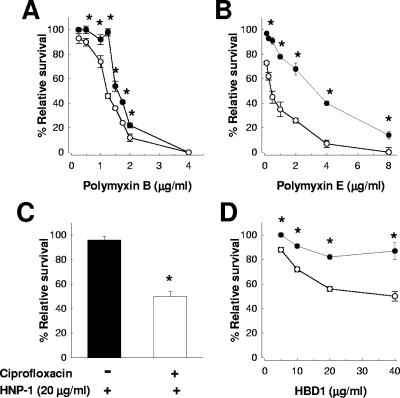

The results shown in Fig. 1 demonstrate that K. pneumoniae 52145 treated with 0.25× the MIC of ciprofloxacin was more sensitive to polymyxin B (Fig. 1A), polymyxin E (Fig. 1B), HNP-1 (Fig. 1C), and HBD1 (Fig. 1D) than the nontreated bacteria. The fact that the APs tested are not structurally related indicates that the sensitivity of ciprofloxacin-treated bacteria was not specific for the AP used.

FIG. 1.

A 1-h treatment with ciprofloxacin increases the sensitivity of K. pneumoniae 52145 to APs. Bacteria were exposed to different amounts of (A) polymyxin B, (B) polymyxin E, (C) HNP-1, and (D) HBD1. Each point in panels A, B, and D represents the mean and standard deviation for six samples from three independently grown batches of bacteria; and significant survival differences (P < 0.05) between bacteria treated with 0.25× the MIC ciprofloxacin (○) and nontreated bacteria (•) are indicated by asterisks. The error bars in panel C display the standard deviation from the mean of three experiments, each one run in duplicate, and an asterisk indicates a significant difference between bacteria treated with ciprofloxacin (white bar) and nontreated ones (black bar).

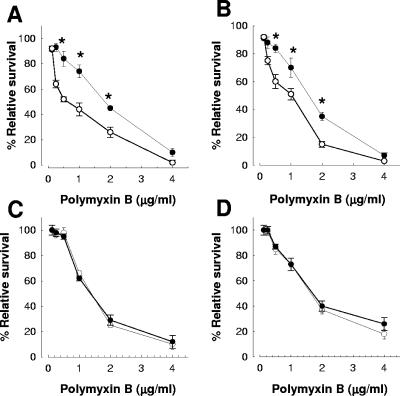

Taking polymyxin B as model of an AP, we asked whether 0.25× the MICs of other quinolones may show effects similar to those observed with ciprofloxacin. Indeed, K. pneumoniae 52145 treated with levofloxacin (Fig. 2A) or nalidixic acid (Fig. 2B) was more sensitive to polymyxin B than the nontreated bacteria. Next, we asked whether a 1-h treatment with 0.25× the MICs of other antibiotics may increase the sensitivity to polymyxin B as well. However, treatment of K. pneumoniae 52145 with 0.25× the MIC of gentamicin (0.062 μg/ml) or ceftazidime (0.031 μg/ml) did not render the bacteria more sensitive to polymyxin B (Fig. 2C and D, respectively).

FIG. 2.

Levofloxacin and nalidixic acid but not gentamicin or ceftazidime increase the sensitivity of K. pneumoniae 52145 to polymyxin B. The effects of a 1-h treatment with (A) levofloxacin, (B) nalidixic acid, (C) gentamicin, and (D) ceftazidime on the survival of bacteria in the presence of polymyxin B are shown. Each point represents the mean and standard deviation of six samples from three independently grown batches of bacteria, and significant survival differences (P < 0.05) between bacteria treated with 0.25× the MIC of antibiotics (○) and nontreated bacteria (•) are indicated by asterisks.

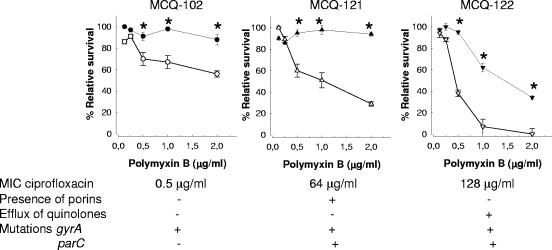

We sought to determine whether ciprofloxacin would also increase the sensitivity to APs of ciprofloxacin-resistant bacteria. We studied the sensitivities to polymyxin B of three clinical K. pneumoniae strains resistant to ciprofloxacin according to the CLSI (formerly NCCLS) breakpoints. Each strain had a different MIC to ciprofloxacin and a different genetic basis for ciprofloxacin resistance (Fig. 3) (31). Thus, it has been shown that the loss of porins OmpK35 and OmpK36 causes an increase in the level of resistance to fluoroquinolones when modifications to topoisomerase II (alone or in combination with changes to topoisomerase IV) are present (7, 8, 30). In addition, it has been shown that active efflux also contributes to quinolone resistance in K. pneumoniae (30). Figure 3 shows that even though there were differences in the relative survival of the strains in the presence of polymyxin B, ciprofloxacin-treated bacteria were more sensitive to polymyxin B than nontreated bacteria (Fig. 3). The amount of ciprofloxacin used was 0.25× the MIC of the sensitive strains (0.0125 μg/ml).

FIG. 3.

A 1-h treatment with ciprofloxacin increases the sensitivity of K. pneumoniae ciprofloxacin-resistant strains to polymyxin B. Each point represents the mean and standard deviation of six samples from three independently grown batches of bacteria, and significant survival differences (P < 0.05) between bacteria treated with ciprofloxacin (white symbols) and nontreated bacteria (black symbols) are indicated by asterisks. The MICs of the strains to ciprofloxacin, whether the strains express porins OmpK35 and OmpK36, whether the strains actively efflux quinolones, and the presence or absence of modifications in gyrA and parC, are also shown.

Ciprofloxacin increases the sensitivity to polymyxins B and E of gram-negative pathogens.

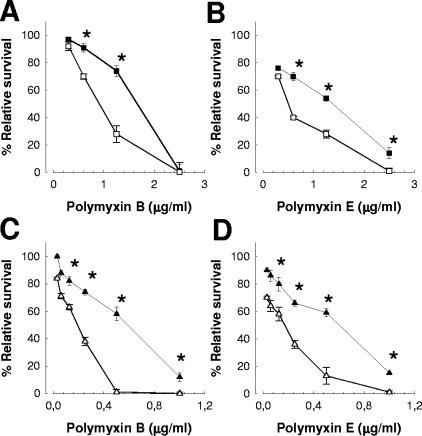

We asked whether quinolones may have similar effects on other gram-negative pathogens. Indeed, treatment of P. aeruginosa (Fig. 4A and B) with 0.25× the MIC of ciprofloxacin (0.03 μg/ml) increased its sensitivity to polymyxins B and E (Fig. 4A and B, respectively). H. influenzae 05-118741 also became more sensitive to polymyxins B and E (Fig. 4C and D, respectively) after a 1-h treatment with 0.25× the MIC of ciprofloxacin (0.015 μg/ml).

FIG. 4.

A 1-h treatment with 0.25× the MIC of ciprofloxacin increases the sensitivities of gram-negative bacteria to APs. P. aeruginosa PAO1 (squares) was exposed to different amounts of (A) polymyxin B and (B) polymyxin E. Symbols: ▪, P. aeruginosa PAO1 not treated with ciprofloxacin; □, P. aeruginosa PAO1 treated with ciprofloxacin. H. influenzae 05-118741 (triangles) was exposed to different amounts of (C) polymyxin B and (D) polymyxin E. Symbols: ▴, H. influenzae not treated with ciprofloxacin; ▵, H. influenzae treated with ciprofloxacin. Each point represents the mean and standard deviation for six samples from three independently grown batches of bacteria, and significant survival differences (P < 0.05) between bacteria treated with 0.25× the MIC of antibiotics (white symbols) and nontreated bacteria (black symbols) are indicated by asterisks.

Ciprofloxacin treatment does not affect the expression of bacterial systems involved in resistance to APs.

Recent studies have demonstrated that ciprofloxacin triggers changes in gene expression (3, 13). It could then be possible that ciprofloxacin may alter the expression of loci involved in resistance to APs. Taking into consideration the previous results, we speculated that ciprofloxacin would down-regulate the expression of these loci, thereby increasing the sensitivity of bacteria to APs. Gram-negative bacteria have developed a variety of strategies to withstand APs; however, it is generally considered that the most important mechanisms of resistance to APs involve surface modifications and specifically those in the LPS molecule (14, 38). In Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium these modifications include (i) addition of aminoarabinose to the phosphate groups at the lipid A level, (ii) replacement of the myristate acyl group of the lipid A by 2-OH-myristate, and (iii) the formation of heptaacylated lipid A by the addition of palmitate (15, 17-19). In K. pneumoniae the most important mechanisms of resistance are the presence of the capsule polysaccharide (6) and the addition of aminoarabinose and palmitate to the lipid A moiety (M. A. Campos and J. A. Bengoechea, unpublished results). Addition of palmitate is dependent on the acyltransferase PagP, whereas the operon pmrHFIJKLM is essential for modification of the lipid A moiety of Klebsiella with aminoarabinose (Campos and Bengoechea, unpublished). We studied whether treatment with ciprofloxacin might affect the expression of these loci. To this end we introduced the cps::lucFF, pagP::lucFF, and pmrH::lucFF transcriptional fusions into K. pneumoniae 52145 and then monitored light production after a 1-h treatment with 0.25× the MIC of ciprofloxacin. Incubation with the antibiotic did not alter the expression of the cps::lucFF fusion (11,922 ± 987 versus 11,577 ± 867 RLU/OD in the absence of ciprofloxacin; P > 0.05), the pagP::lucFF fusion (12,212 ± 978 versus 12,613 ± 1114 RLU/OD in the absence of ciprofloxacin; P > 0.05), or the pmrH::lucFF fusion (13,074 ± 943 versus 13,001 ± 541 RLU/OD in the absence of ciprofloxacin; P > 0.05). These results argue against our initial hypothesis that ciprofloxacin would trigger changes in the expression of loci involved in resistance to APs.

Ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin permeabilize the outer membrane.

A remaining question is to explain how quinolone treatment renders gram-negative bacteria more sensitive to APs. It has been shown that quinolones chelate divalent cations (24, 29). Since the molecular basis of the integrity of the OM lies in the cation binding sites of LPS, it is tempting to speculate that quinolones may disturb the stability of the OM, thereby facilitating the actions of APs (37, 41). This proposed mechanism is similar to that of EDTA (37, 41). However, this hypothesis has been disputed, and recently, Lindner and colleagues have shown that quinolones do not chelate cations from their LPS-binding sites (25). It must be noted that purified LPS does not necessarily mimic the complex environment of the OM, and therefore, care should be taken to directly extrapolate the findings obtained with purified LPS to whole bacteria (33).

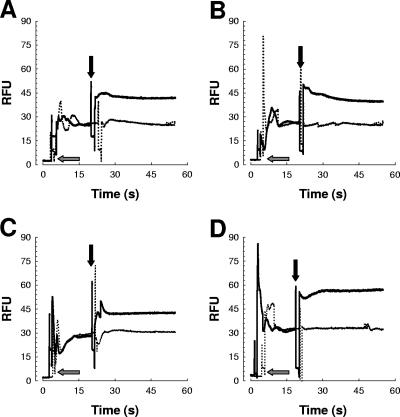

To determine whether the quinolones ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin affect the OM, we performed the NPN assay, which is commonly used to evaluate the interaction of compounds with the OM. No fluorescence accumulation was evident when ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin was added to the buffer containing NPN without cells (data not shown). The addition of ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin to K. pneumoniae cells in the presence of NPN caused an increase in fluorescence (Fig. 5A and B, respectively, straight lines). To confirm the disrupted action on the OM via the chelation of divalent cations with quinolones, we asked whether divalent cations could inhibit the increase in NPN fluorescence. We found that addition of Ca2+ inhibited the increase in NPN fluorescence induced by ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin in K. pneumoniae (Fig. 5A and B, respectively, dotted lines). Similar results were obtained when Mg2+ instead of Ca2+was added (data not shown). We sought to determine whether Ca2+ would then inhibit the increased sensitivity to polymyxin B after treatment of the bacteria with ciprofloxacin. The IC50 of polymyxin B for K. pneumoniae treated with 0.25× the MIC of ciprofloxacin was 0.8 ± 0.1 μg/ml, whereas the IC50 of polymyxin B for K. pneumoniae treated with 0.25× the MIC of ciprofloxacin and 10 mM Ca2+ was 2.3 ± 0.2 μg/ml, which was not significantly different (P > 0.05) from those for K. pneumoniae treated with 10 mM Ca2+ and nontreated bacteria (2.1 ± 0.1 μg/ml and 2.2 ± 0.4 μg/ml, respectively).

FIG. 5.

Time course of increase in NPN fluorescence intensity in K. pneumoniae 52145 (A and B) and P. aeruginosa PAO1 (C and D) cells treated with quinolones. At 5 s NPN was added to intact cells (gray arrows), and at 20 s compounds were added (black arrows). (A) Ciprofloxacin (straight line) or ciprofloxacin and 10 mM Ca2+ (dotted line) were added to K. pneumoniae intact cells; (B) levofloxacin (straight line) or levofloxacin and 10 mM Ca2+ (dotted line) were added to K. pneumoniae intact cells; (C) ciprofloxacin (straight line) or ciprofloxacin and 10 mM Ca2+ (dotted line) were added to P. aeruginosa intact cells; (D) levofloxacin (straight line) or levofloxacin and 10 mM Ca2+ (dotted line) were added to P. aeruginosa intact cells. The data are representative of three separate independent experiments (coefficient of variation, less than 4%).

These findings showing a direct effect of quinolones on the OM prompted us to study whether the effects of quinolones would be reversible. To this end, after 1 h of treatment with the antibiotic, K. pneumoniae bacteria were washed with prewarmed LB medium to remove ciprofloxacin and were further incubated without the antibiotic. Polymyxin B susceptibility was checked at different time points. The results showed that after 10 min of incubation without ciprofloxacin the bacteria became as sensitive to polymyxin B as the bacteria that had never been treated with ciprofloxacin (IC50s, 2.4 ± 0.2 μg/ml and 2.7 ± 0.3 μg/ml, respectively).

Finally, we asked whether quinolones may affect the OMs of other gram-negative bacteria as well. Addition of ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin to P. aeruginosa cells also triggered an increase in fluorescence (Fig. 5C and D, straight lines). This effect was also inhibited by adding Ca2+ (Fig. 5C and D, dotted lines).

In summary, our findings support the idea that quinolones interact with the OM and increase its permeability, while divalent cations antagonize this action. Understanding of the discrepancy between our data and those of other investigators would probably require a strict comparison of the experimental conditions.

Ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin increase the binding of APs to the surface.

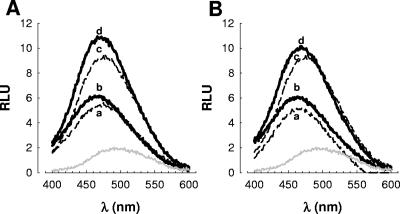

We evaluated whether ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin indeed increase the binding of APs to the OM by using dansylated polymyxin B. The dansylated peptide exhibits a low fluorescent yield when it is diluted into aqueous buffer; however, the fluorescence yield increases, with the maximum fluorescence shifting to a lower wavelength in a hydrophobic environment, such as a bacterial membrane (32, 35). Therefore, there is a correlation between fluorescence and the amount of dansylated polymyxin B bound to the bacteria (2, 32).

Figure 6 shows that dansyl polymyxin B (0.5 μM) exhibited a low fluorescence yield when it was incubated in buffer only (λmax, 490 nm) (Fig. 6A and B, gray lines). When it was incubated with nontreated K. pneumoniae (Fig. 6A and B, lines a), there was an increase in the fluorescence yield (λmax, 475 nm) which was higher in the case of bacteria treated with 0.25× the MIC of ciprofloxacin (λmax, 466 nm) (Fig. 6A, line b) or with 0.25× the MIC of levofloxacin (λmax, 464 nm) (Fig. 6B, line b). These experiments were repeated with 1 μM dansyl polymyxin B. The fluorescence yield in buffer only was similar to that obtained with 0.5 μM dansyl polymyxin B (data not shown). As before, nontreated bacteria showed a lower fluorescence yield (Fig. 6A and B, lines c) than ciprofloxacin-treated bacteria (Fig. 6A, line d) and levofloxacin-treated bacteria (Fig. 6B, line d). Unlabeled polymyxin B outcompeted dansylated polymyxin B, showing that binding was specific and not due to nonspecific features of the dansyl group (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Binding of dansyl polymyxin B to K. pneumoniae 52145 treated with ciprofloxacin (A) and levofloxacin (B). Lines: a, 0.5 μM dansyl polymyxin B was added to nontreated K. pneumoniae cells; b, 0.5 μM dansyl polymyxin B was added to bacteria treated with 0.25× the MIC of a quinolone; c, 1 μM dansyl polymyxin B was added to nontreated K. pneumoniae cells; d, 1 μM dansyl polymyxin B was added to quinolone-treated bacteria. Gray line, 0.5 μM dansyl polymyxin B was added to 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.5). The data are representative of four separate independent experiments (coefficient of variation, less than 5%).

Conclusions.

Our results show that a 1-h treatment with 0.25× the MICs of quinolones increases the sensitivities of gram-negative pathogens to APs, and this is also true for strains resistant to quinolones. Our data argue against the possibility that quinolones alter the expression of loci involved in the resistance to APs but point to a direct effect on the OM. We have shown that quinolones interact with the OM probably by displacement of divalent cations from their LPS-binding sites, and this action increases the binding of APs to the outer membrane.

Potential therapeutic implications.

We believe that our results may open new avenues of research for the design of new therapeutic alternatives to conventional antibacterial treatments. The use of compounds based on the structures of quinolones but modeled to increase their membrane action should be useful for rendering bacteria susceptible to APs naturally present at the sites of infection. We are aware that in healthy tissues the concentration of APs is relatively low, which may cast doubts on the feasibility of this approach. Nevertheless, ample evidence demonstrates that the amounts of APs increase rapidly in infected tissues and that several APs are present at the sites of infection, acting cooperatively to kill bacteria (11, 12, 20, 21, 39).

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Oliver for critically reading the manuscript and members of J. A. Bengoechea's lab for helpful discussions. We are grateful to J. S. Gunn and M. Hensel for plasmid pGPL01.

The fellowship support to M. A. Campos from Govern Illes Balears is gratefully acknowledged. J.A.B. is the recipient of a Contrato de Investigador from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria. This work has been funded by grants from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (PI01/3095 and PI04/1854 to J.A.B.), Red Respira (RTIC C03/11, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain), and Red REIPI (RTC C03/14 Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bengoechea, J. A., R. Díaz, and I. Moriyón. 1996. Outer membrane differences between pathogenic and environmental Yersinia enterocolitica biogroups probed with hydrophobic permeants and polycationic peptides. Infect. Immun. 64:4891-4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bengoechea, J. A., B. Lindner, U. Seydel, R. Díaz, and I. Moriyón. 1998. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia pestis are more resistant to bactericidal cationic peptides than Yersinia enterocolitica. Microbiology 144:1509-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brazas, M. D., and R. E. Hancock. 2005. Ciprofloxacin induction of a susceptibility determinant in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3222-3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breines, D. M., and J. C. Burnham. 1994. Modulation of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial expression and adherence to uroepithelial cells following exposure of logarithmic phase cells to quinolones at subinhibitory concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 34:205-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brogden, K. A. 2005. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:238-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campos, M. A., M. A. Vargas, V. Regueiro, C. M. Llompart, S. Alberti, and J. A. Bengoechea. 2004. Capsule polysaccharide mediates bacterial resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Immun. 72:7107-7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deguchi, T., A. Fukuoka, M. Yasuda, M. Nakano, S. Ozeki, E. Kanematsu, Y. Nishino, S. Ishihara, Y. Ban, and Y. Kawada. 1997. Alterations in the GyrA subunit of DNA gyrase and the ParC subunit of topoisomerase IV in quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:699-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deguchi, T., T. Kawamura, M. Yasuda, M. Nakano, H. Fukuda, H. Kato, N. Kato, Y. Okano, and Y. Kawada. 1997. In vivo selection of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with enhanced quinolone resistance during fluoroquinolone treatment of urinary tract infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1609-1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doss, S. A., G. S. Tillotson, and S. G. Amyes. 1993. Effect of sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 75:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans, M. E., D. J. Feola, and R. P. Rapp. 1999. Polymyxin B sulfate and colistin: old antibiotics for emerging multiresistant gram-negative bacteria. Ann. Pharmacother. 33:960-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finlay, B. B., and R. E. Hancock. 2004. Can innate immunity be enhanced to treat microbial infections? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:497-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallo, R. L., M. Murakami, T. Ohtake, and M. Zaiou. 2002. Biology and clinical relevance of naturally occurring antimicrobial peptides. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 110:823-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gmuender, H., K. Kuratli, K. Di Padova, C. P. Gray, W. Keck, and S. Evers. 2001. Gene expression changes triggered by exposure of Haemophilus influenzae to novobiocin or ciprofloxacin: combined transcription and translation analysis. Genome Res. 11:28-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groisman, E. A. 1994. How bacteria resist killing by host-defence peptides. Trends Microbiol. 2:444-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunn, J. S., K. B. Lim, J. Krueger, K. Kim, L. Guo, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1998. PmrA-PmrB-regulated genes necessary for 4-aminoarabinose lipid A modification and polymyxin resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 27:1171-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunn, J. S., and S. I. Miller. 1996. Pho-PhoQ activates transcription of pmrAB, encoding a two-component regulatory system involved in Salmonella typhimurium antimicrobial peptide resistance. J. Bacteriol. 178:6857-6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunn, J. S., S. S. Ryan, J. C. Van Velkinburgh, R. K. Ernst, and S. I. Miller. 2000. Genetic and functional analysis of a PmrA-PmrB-regulated locus necessary for lipopolysaccharide modification, antimicrobial peptide resistance, and oral virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 68:6139-6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo, L., K. B. Lim, J. S. Gunn, B. Bainbridge, R. P. Darveau, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1997. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phop-phoQ. Science 276:250-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo, L., K. B. Lim, C. M. Poduje, M. Daniel, J. S. Gunn, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1998. Lipid A acylation and bacterial resistance against vertebrate antimicrobial peptides. Cell 95:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hancock, R. E., and G. Diamond. 2000. The role of cationic antimicrobial peptides in innate host defences. Trends Microbiol. 8:402-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hancock, R. E., and M. G. Scott. 2000. The role of antimicrobial peptides in animal defenses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8856-8861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hancock, R. E. W., and D. S. Chapple. 1999. Peptide antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1317-1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermsen, E. D., C. J. Sullivan, and J. C. Rotschafer. 2003. Polymyxins: pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and clinical applications. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 17:545-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lecomte, S., M. H. Baron, M. T. Chenon, C. Coupry, and N. J. Moreau. 1994. Effect of magnesium complexation by fluoroquinolones on their antibacterial properties. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2810-2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindner, B., A. Wiese, K. Brandenburg, U. Seydel, and A. Dalhoff. 2002. Lack of interaction of fluoroquinolones with lipopolysaccharides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1568-1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loh, B., C. Grant, and R. E. W. Hancock. 1984. Use of the fluorescent probe 1-N-phenylnaphthylamine to study the interactions of aminoglycoside antibiotics with the outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 26:546-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loubeyre, C., J. F. Desnottes, and N. Moreau. 1993. Influence of sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibacterials on the surface properties and adhesion of Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 31:37-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luck, P. C., J. W. Schmitt, A. Hengerer, and J. H. Helbig. 1998. Subinhibitory concentrations of antimicrobial agents reduce the uptake of Legionella pneumophila into Acanthamoeba castellanii and U937 cells by altering the expression of virulence-associated antigens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2870-2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall, A. J., and L. J. Piddock. 1994. Interaction of divalent cations, quinolones and bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 34:465-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez-Martinez, L., I. Garcia, S. Ballesta, V. J. Benedi, S. Hernandez-Alles, and A. Pascual. 1998. Energy-dependent accumulation of fluoroquinolones in quinolone-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1850-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez-Martinez, L., A. Pascual, M. C. Conejo, I. Garcia, P. Joyanes, A. Domenech-Sanchez, and V. J. Benedi. 2002. Energy-dependent accumulation of norfloxacin and porin expression in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and relationship to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3926-3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore, R. A., N. C. Bates, and R. E. Hancock. 1986. Interaction of polycationic antibiotics with Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide and lipid A studied by using dansyl-polymyxin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 29:496-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore, R. A., and R. E. Hancock. 1986. Involvement of outer membrane of Pseudomonas cepacia in aminoglycoside and polymyxin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 30:923-926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nassif, X., J. M. Fournier, J. Arondel, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1989. Mucoid phenotype of Klebsiella pneumoniae is a plasmid-encoded virulence factor. Infect. Immun. 57:546-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newton, B. A. 1955. A fluorescent derivative of polymyxin: its preparation and use in studying the site of action of the antibiotic. J. Gen. Microbiol. 12:226-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicolas, P., and A. Mor. 1995. Peptides as weapons against microorganisms in the chemical defence system of vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:277-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikaido, H., and M. Vaara. 1985. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol. Rev. 49:1-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peschel, A. 2002. How do bacteria resist human antimicrobial peptides? Trends Microbiol. 10:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sawyer, J. G., N. L. Martin, and R. E. Hancock. 1988. Interaction of macrophage cationic proteins with the outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 56:693-698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trancassini, M., M. I. Brenciaglia, M. C. Ghezzi, P. Cipriani, and F. Filadoro. 1992. Modification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors by sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. J. Chemother. 4:78-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaara, M. 1992. Agents that increase the permeability of the outer membrane. Microbiol. Rev. 56:395-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vranes, J., Z. Zagar, and S. Kurbel. 1996. Influence of subinhibitory concentrations of ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin and azithromycin on the morphology and adherence of P-fimbriated Escherichia coli. J. Chemother. 8:254-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]