Abstract

We measured time-kills and postantifungal effects (PAFEs) of caspofungin against Candida albicans, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata isolates. One-hour exposure to caspofungin during PAFE experiments accounted for the majority of killing during time-kill experiments. Regrowth of all isolates was inhibited for at least 24 h following drug washout.

Caspofungin inhibits the synthesis of the fungal cell wall component β-1,3-d-glucan and is effective against mucocutaneous (20) and invasive candidiasis (15, 21). The drug exhibits concentration-dependent fungicidal or fungistatic activity against diverse Candida species (2, 3, 7, 17). In addition, caspofungin exerts prolonged postantifungal effects (PAFEs) against Candida albicans and C. lusitaniae (6, 8, 14). In this study, we performed simultaneous time-kill and PAFE experiments on C. albicans (n = 4), C. parapsilosis (n = 2), and C. glabrata (n = 2) isolates.

Prior to testing, isolates were subcultured twice on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plates. MICs of caspofungin were determined against test isolates using a broth microdilution technique (16). MIC2 end points (i.e., visual “prominent growth reduction”) were read at 24 h in RPMI 1640 buffered to a pH of 7.0 with MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid; RPMI 1640 medium). MICs are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Caspofungin MICs

| Isolate | MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|

| C. albicans S | 0.125 |

| C. albicans A | 0.25 |

| C. albicans 1 | 0.015 |

| C. albicans 2 | 0.003 |

| C. parapsilosis 1 | 0.5 |

| C. parapsilosis 2 | 0.06 |

| C. glabrata 1 | 0.25 |

| C. glabrata 2 | 0.25 |

For time-kills and PAFEs, colonies from 48-hour cultures on SDA plates were suspended in 9 ml of sterile water and adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard (7, 8, 11, 12, 17). One milliliter of the suspension was added to 9 ml of RPMI 1640 medium with or without caspofungin, and the solution was incubated at 35°C with agitation. At the desired time points, 100 μl was obtained from each solution, serially diluted, and plated on SDA plates for colony enumeration. We simultaneously set up time-kill and PAFE experiments for control testing (no drug) and testing at 0.25, 1, 4, and 16 times the MIC in duplicate tubes (labeled “time-kill” and “PAFE”). After 1 hour of incubation, we centrifuged the cells in the “PAFE” tubes at 1,400 × g for 10 min, washed them three times, and resuspended them in warm RPMI medium (9 ml) prior to reincubation. Both sets of tubes were plated on SDA plates after 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h for CFU determination. Time-kill and PAFE experiments were conducted at least twice for each isolate.

During time-kill experiments, caspofungin at concentrations of 4 and 16 times the MIC caused significant reductions in the starting inoculum of each isolate (Table 2). The extent of killing did not correlate with the MIC. Representative kill curves for time-kill experiments are shown in Fig. 1A and 2A.

TABLE 2.

Maximal reductions in starting inocula of Candida isolates during 24-h time-kill and PAFE experimentsc

| Caspofungin concn (×MIC) | Isolate | Killing (log)

|

PAFE/time- kill killinga | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-kill | PAFE | |||

| 16 | C. albicans S | 2.52 | 2.72 | 100 |

| 16 | C. albicans A | 0.94 | 0.68 | 55.0 |

| 16 | C. albicans 1 | 1.57 | 1.55 | 95.0 |

| 16 | C. albicans 2 | 1.70 | 1.60 | 79.4 |

| 16 | C. parapsilosis 1 | 2.03 | 1.60 | 37.2 |

| 16 | C. parapsilosis 2 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 100 |

| 16 | C. glabrata 1 | 0.57 | 0.35 | 60.3 |

| 16 | C. glabrata 2 | 1.66 | 1.43 | 58.9 |

| 4 | C. albicans S | 2.46 | 2.49 | 100 |

| 4 | C. albicans A | 0.88 | 0.74 | 72.4 |

| 4 | C. albicans 1 | 1.34 | 1.31 | 93.3 |

| 4 | C. albicans 2 | 1.43 | 0.80 | 23.4 |

| 4 | C. parapsilosis 1 | 1.31 | 1.28 | 93.3 |

| 4 | C. parapsilosis 2 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 100 |

| 4 | C. glabrata 1 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 85.1 |

| 4 | C. glabrata 2 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 100 |

| 1 | C. albicans S | 2.25 | 1.80 | 35.5 |

| 1 | C. albicans A | 0.38 | 0.50 | 100 |

| 1 | C. albicans 1 | 1.44 | 1.17 | 53.7 |

| 1 | C. albicans 2 | NAb | NA | NA |

| 1 | C. parapsilosis 1 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 81.3 |

| 1 | C. parapsilosis 2 | NA | NA | NA |

| 1 | C. glabrata 1 | 0.48 | 0.26 | 60.3 |

| 1 | C. glabrata 2 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 91.2 |

Ratio of the log killing during PAFE experiments to the log killing during time-kill experiments.

NA, not applicable; there were no reductions in colony counts compared to the starting inoculum.

Representative data for each isolate from one of at least two separate experiments are shown.

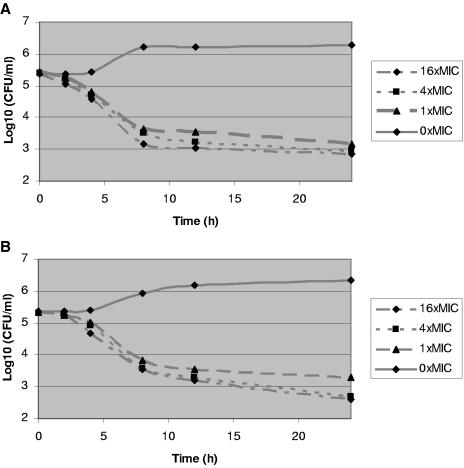

FIG.1.

Kill curves for time-kill (A) and postantifungal effect (B) experiments on C. albicans S. The kill curves at 0.25 times the MIC are not presented but did not show reductions in colony counts from the starting inocula.

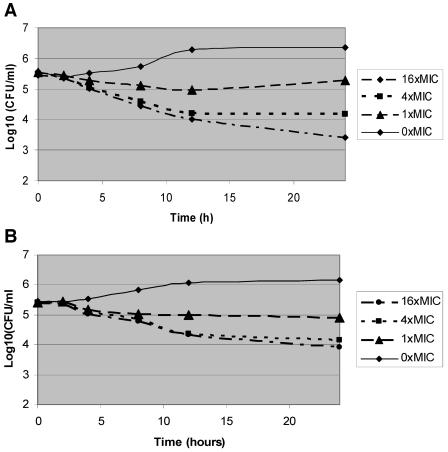

FIG.2.

Kill curves for time-kill (A) and postantifungal effect (B) experiments on C. parapsilosis 1. The kill curves at 0.25 times the MIC are not presented but did not show reductions in colony counts from the starting inocula.

During PAFE experiments, 1-hour exposure of all isolates to caspofungin at 4 and 16 times the MIC also caused large reductions in colony counts that persisted for the 24-h testing period (Table 2; Fig. 1B and 2B). Moreover, the PAFE after a 1-hour exposure generally accounted for the majority of killing observed during time-kill experiments (Table 2). At 16 times the MIC, for example, a 1-hour exposure to caspofungin resulted in colony count reductions that were 37 to 100% of those seen with continuous 24-h exposure; similar results were obtained at 4 times the MIC and at the MIC.

For each isolate, we retested selected colonies that were not killed by exposure to caspofungin during time-kill and PAFE experiments. MICs of the “persisters” were identical to the MIC of the parent strain. Growth rates of the persisters were also indistinguishable from those of the parent strains at both 30 and 35°C.

The most notable findings of this study are the PAFEs we demonstrated. As in previous reports, caspofungin exerted prolonged PAFEs against C. albicans (1, 8). We found similar PAFEs against C. parapsilosis and C. glabrata isolates. More strikingly, 1-hour exposure to caspofungin accounted for up to 100% of the overall killing observed during time-kill experiments and inhibited regrowth of isolates for at least 24 h. The results are consistent with a rapid onset of sustained anticandidal activity by caspofungin, which might be explained by different mechanisms. As one mechanism, caspofungin might rapidly associate with its target and exert prolonged effects on the β-1,3-d-glucan synthase enzyme complex. Alternatively, the drug, as a large lipopeptide with a fatty acid side chain (5), could rapidly intercalate with the phospholipid bilayer of the candidal cell membrane and subsequently access its target over time. Regardless of the specific mechanism, caspofungin, similar to β-lactams (9, 10, 18), is likely to be most active against proliferating cells, which would be consistent with our observation that killing increased over several hours.

It is also notable that persister Candida isolates that were not killed by caspofungin did not exhibit elevated MICs upon retesting, indicating that growth was not due to acquired resistance or preexisting resistant subpopulations. Rather, it is possible that persisters were dormant or replicated slowly in the presence of caspofungin (4, 17, 19). If so, they were not irreversibly impaired, as growth in liquid media after recovery from time-kill and PAFE experiments was not reduced.

We demonstrated that caspofungin at concentrations above the MICs significantly reduced the burden of all eight Candida isolates during time-kill experiments. These reductions, however, did not fulfill strict definitions of fungicidal activity (i.e., ≥3-log reduction) (11). Previous studies have shown that caspofungin exhibits fungicidal or fungistatic activity depending on the isolate and test conditions (2, 3, 7, 17). Echinocandins are less consistently fungicidal in RPMI medium than antibiotic medium 3 (7, 8, 17). Incubation times can also influence results, as indicated by our finding that prolonged incubation of 48 h did achieve fungicidal activity against at least one isolate (C. albicans S) (data not shown). In assessing our results, it is notable that concurrent time-kill experiments on several isolates with the fungistatic agent fluconazole were consistent with growth inhibition but failed to show reductions in starting inocula (data not shown).

Although the clinical implications of in vitro killing and PAFEs are unproven (1), our data suggest that treatment strategies that both optimize caspofungin peak concentrations and account for prolonged growth inhibition might be the best approach to candidiasis. As such, less-frequent administration of larger, cumulative doses might be at least as efficacious as more-frequent, smaller doses, especially given the persistence of caspofungin within tissues in vivo (13). This conclusion is consistent with results of a recent pharmacodynamic study of caspofungin during murine candidiasis (13). Trials comparing high-dose, once- or twice-weekly caspofungin regimens against standard daily dosing should be considered.

Acknowledgments

Experiments were conducted in the laboratories of C. J. Clancy and M. H. Nguyen at the North Florida/South Georgia VA Medical Center, Gainesville, FL. The project was conducted as part of the University of Florida Mycology Research Unit.

This project was supported by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andes, D. 2003. In vivo pharmacodynamics of antifungal drugs in treatment of candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1179-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barchiesi, F., E. Spreghini, S. Tomassetti, D. Arzeni, D. Giannini, and G. Scalise. 2005. Comparison of the fungicidal activites of caspofungin and amphotericin B against Candida glabrata. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4989-4992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartizal, K., C. J. Gill, G. K. Abruzzo, A. M. Flattery, L. Kong, P. M. Scott, J. G. Smith, C. E. Leighton, A. Bouffard, J. F. Dropinski, and J. Balkovec. 1997. In vitro preclinical evaluation studies with the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2326-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryan, L. E. 1989. Two forms of antimictobial resistance: bacterial persistence and positive function resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 23:817-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denning, D. W. 2003. Echinocadin antifungal drugs. Lancet 362:1142-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiBonaventura, G., I. Spedicato, C. Picciani, D. D'Antonio, and R. Piccolomini. 2004. In vitro pharmacodynamic characteristics of amphotericin B, caspofungin, fluconazole, and voriconazole against bloodstream isolates of infrequent Candida species from patients with hematologic malignancies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4453-4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ernst, E. J., M. E. Klepser, M. E. Ernst, S. A. Messer, and M. A. Pfaller. 1999. In vitro pharmacodynamic properties of MK-0991 determined by time-kill methods. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 33:75-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernst, E. J., M. E. Klepser, and M. A. Pfaller. 2000. Postantifungal effects of echinocandin, azole, and polyene antifungal agents against Candida albicans and Crytpococcus neoformans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1108-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunnison, J. B., M. A. Fraher, and E. Jawetz. 1963. Persistence of Staphylococcus aureus in penicillin in vitro. J. Gen. Microbiol. 34:335-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, K. S., and B. F. Anthony. 1981. Importance of bacterial growth phase in determining minimal batericidal concentration of penicillin and methicillin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1075-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klepser, M. E., E. J. Ernst, R. E. Lewis, M. E. Ernst, and M. A. Pfaller. 1998. Influence of test conditions on antifungal time-kill curve results: Proposal for standardized methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1207-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klepser, M. E., R. E. Lewis, E. J. Ernst, C. R. Petzold, E. M. Bailey, D. S. Burgess, P. L. Carver, M. K. Lacy, R. C. Mercier, D. P. Nicolau, G. G. Zhanel, and M. A. Pfaller. 2001. Multi-center evaluation of antifungal time-kill methods. Infect. Dis. Pharmacother. 5:29-41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louie, A., M. Deziel, W. Liu, M. F. Drusano, T. Gumbo, and G. L. Drusano. 2005. Pharmacodynamics of caspofungin in a murine model of systemic candidiasis: importance of persistence of caspofungin in tissues to understanding drug activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:5058-5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manavathu, E. K., M. S. Ramesh, I. Baskaran, L. T. Ganesan, and P. H. Chandrasekar. 2004. A comparative study of the post-antifungal effect (PAFE) of amphotericin B, triazoles and echinocandins on Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:386-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mora-Duarte, J., R. Betts, C. Rotstein, A. L. Colombo, L. Thompson-Moya, J. Smietana, R. Lupinacci, C. Sable, N. Kartsonis, and J. Perfect. 2002. Comparison of caspofungin and amphotericin B for invasive candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:2020-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odds, F. C., M. Motyl, R. Andrade, J. Bille, E. Cantón, M. Cuenca-Estrella, A. Davidson, C. Durussel, D. Ellis, E. Foraker, A. W. Fothergill, M. A. Ghannoum, R. A. Giacobbe, M. Gobernado, R. Handke, M. Laverdière, W. Lee-Yang, W. G. Merz, L. Ostrosky-Zeichner, J. Pemán, S. Perea, J. R. Perfect, M. A. Pfaller, L. Proia, J. H. Rex, M. G. Rinaldi, J. Rodriguez-Tudela, W. A. Schell, C. Shields, D. A. Sutton, P. E. Verweij, and D. W. Warnock. 2004. Interlaboratory comparison of results of susceptibility testing with caspofungin against Candida and Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3475-3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, and R. N. Jones. 2003. In vitro activities of caspofungin compared with those of fluconazole and itraconazole against 3,959 clinical isolates of Candida spp., including 157 fluconazole-resistant isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1068-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuomanen, E., R. Cozens, W. Tosch, O. Zak, and A. Tomasz. 1986. The rate of killing of Escheruchia coli is strictly proportional to the rate of bacterial growth. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:1297-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turnidge, J. D., S. Gudmundsson, B. Vogelman, and W. A. Craig. 1994. The postantibiotic effect of antifungal agents against common pathogenic yeasts. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 34:83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villanueva, A., E. Gotuzzo, E. G. Arathoon, L. M. Noriega, N. A. Kartsonis, R. J. Lupinacci, J. M. Smietana, M. J. DiNubile, and C. A. Sable. 2002. A randomized double-blind study of caspofungin versus fluconazole for the treatment of esophageal candidiasis. Am. J. Med. 114:294-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh, T. J. 2002. Echinocandins—an advance in the primary treatment of invasive candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:2070-2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]