Abstract

We isolated 19 lincomycin-resistant Bacillus subtilis mutants by expressing lmrB encoding a putative multidrug efflux protein. Eighteen of the mutants altered at two regions (−3 to −1 and +15) immediately downstream of the −10 region of the lmr promoter increased lmr transcription in vivo and in vitro.

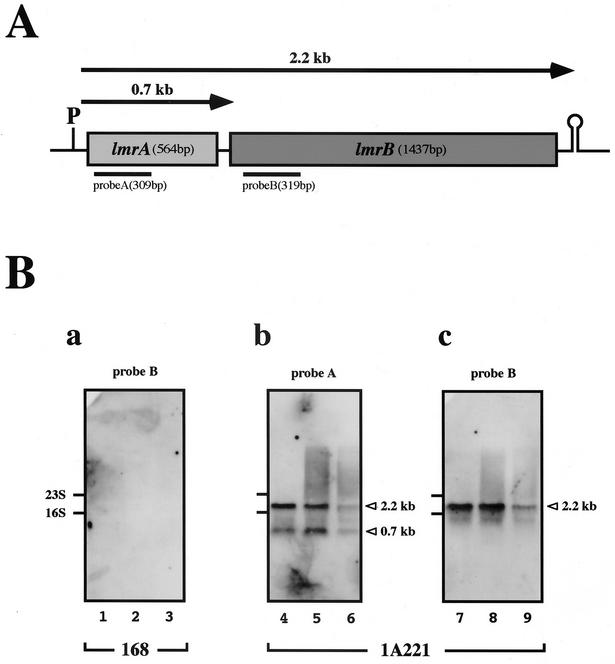

Bacteria can become resistant to various drugs and chemicals through the expression of genes for membrane-spanning drug efflux transporters (9, 10). Many genes for drug transporters form operons with additional genes that are transcriptional regulators, such as Bacillus subtilis bmr/bmrR (1) and Escherichia coli emrAB/emrR (7). We reported that the lmr operon consists of lmrA and lmrB in B. subtilis (Fig. 1A) and that the lin-2 mutation, which confers lincomycin resistance on B. subtilis 1A221, arises by replacing two nucleotides (A and G at positions −1 and +15 replaced with C and T, respectively) immediately downstream of the predicted −10 region of the lmr promoter (6). LmrA should be a transcriptional regulator as it has a DNA-binding motif like that of TetR (2), and LmrB should be a drug efflux pump as it has two conserved sequence motifs for translocation (8) and for drug extrusion (4).

FIG. 1.

Northern hybridization of lmr operon of B. subtilis 168 and lincomycin-resistant strain 1A221. (A) Schematic representation of lmr operon expression. P and stem-loop structure, putative promoter for σA and a ρ-independent transcriptional terminator, respectively; arrows, transcripts from the putative lmr promoter of 1A221; black bars, two fragments used as probes in Northern hybridization. (B) Northern hybridization of total RNA prepared from 168 and 1A221 using DIG-labeled probes A (b) and B (a and c). Total RNA was prepared from 168 and 1A221 cells at three growth phases (lanes 1, 4, and 7, early log; lanes 2, 5, and 8, late log; lanes 3, 6, and 9, stationary) without lincomycin. Arrowheads, two main transcriptional products (2.2 and 0.7 kb). Results for the 168 preparation obtained with probe A were identical to those obtained with probe B. The experiment was repeated twice, and photographs were almost identical.

We examined whether these nucleotide changes affect levels of transcription of the lmr genes in 1A221 by using Northern hybridization. Total B. subtilis 168 and 1A221 RNAs (10 μg) were resolved in 1.5% agarose gels containing 2.2 M formaldehyde and then transferred to Gene Screen Plus nylon membranes (NEN Life Science Products) as described by Sambrook et al. (11). We detected lmrA and lmrB mRNA by using labeled probes (probe A for lmrA and probe B for lmrB in Fig. 1A and B) with the digoxigenin (DIG) system (Roche Diagnostics). To prepare DIG-labeled RNA probes for lmrA and lmrB, 309 bp of lmrA fragments and 319 bp of lmrB fragments near the regions of both genes encoding the NH2 termini of the gene products were amplified by PCR with specific oligonucleotide pairs PR1 (5′-gcgcaagcttATGGAGATTCCCGTGAGAAA-3′) and PR2 (5′-gccgagatctCCCACAGGCAAGCCTTCAAT-3′) and PR3 (5′-gcgcaagcttAGCAATACAAAGTGATGCCG-3′) and PR4 (5′-gccgagatctAAGTGCCTGAACGATCCTTG-3′), respectively. These primers contain linker DNA for HindIII or BglII sites (linker regions are in lowercase). The PCR products were digested with HindIII and BglII and inserted into pGEM-3Zf(+) (Promega) cleaved by HindIII and BamHI within its multicloning site. Inserted fragments were reamplified by PCR with the pGEM flanking region containing the T7 promoter by using primers PR5 (5′-GTTTTCCCAGTCACGACG-3′) and PR6 (5′-GAATTGTGAGCGGATAAC-3′). Purified PCR products (100 ng) were digested with HindIII and used as templates for DIG labeling by transcription with T7 RNA polymerase. After the reaction was stopped, products were precipitated with 75% cold ethanol, dried, and dissolved in water treated with diethyl pyrocarbonate, and 20 to 100 ng was used as hybridization probes. Probe detection was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics). Probe A detected 2.2- and 0.7-kb bands throughout all growth stages of 1A221 (Fig. 1B, b), and probe B identified a major 2.2-kb band (Fig. 1B, c), confirming that lmrA and lmrB form an operon. In addition, lmrA was solely transcribed as 0.7-kb RNA. In contrast, neither probe A nor probe B detected transcripts in 168. These results indicated that the lin-2 mutation causes a high level of lmr transcription in 1A221 during both the exponential and stationary growth phases.

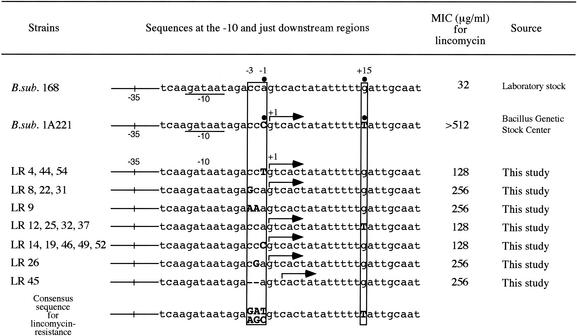

We further isolated and characterized 19 spontaneous lincomycin-resistant mutants that expressed lmrB. Fifty-four colonies were isolated from 1010 cells of B. subtilis 168 spread on 50 Luria-Bertani agar plates with 100 μg of lincomycin/ml at 37°C for 12 h. Nineteen strains that were positive for the lmrB gene were selected by dot blot Northern hybridization using probe B. Sequencing the promoter and lmrA region showed that, in 18 of the mutants, none of the nucleotides comprising the lmrA coding region was altered. However, we located an alteration at the lmrA termination codon (TAA to TCA coding Ser) in one mutant. Figure 2 aligns and compares the sequences of −10 and downstream regions in the 18 mutants with those of 168 and 1A221. Nucleotide alterations in all of these mutants were localized at the −3 to −1 region and/or the +15 position immediately downstream of the −10 region. Two nucleotides corresponding to −3 and −2 were deleted from LR 45. Mutants LR 8, 9, 22, 26, and 31, each harboring a mutation at −3 and/or −2 where C was replaced with G or A, were highly resistant to lincomycin. The single replacement of G at position +15 with T in LR 12, 25, 32, and 37 and of A at position −1 with C or T in LR 4, 14, 19, 44, 46, 49, 52, and 54 caused a low level of lincomycin resistance. Deleting the two nucleotides in LR 45 resulted in A, G, T, and T at positions −3, −2, −1, and +15, respectively, and high resistance to lincomycin. Amplified PCR fragments containing the mutated nucleotides from each mutant reproducibly conferred lincomycin resistance on the wild type by DNA-mediated transformation.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of sequences at −10 and downstream of lmr promoters of 168, 1A221, and 18 lincomycin-resistant mutants. PCR products were prepared from 168, 1A221, and mutant chromosomal DNA with the primer set PR7 (5′-TGCTGCCGACGTTAACAATC-3′) and PR8 (5′-AGCAGTCCTGAAACAGGAAC-3′) to sequence promoter and lmrA regions. Uppercase letters, replaced nucleotides in 1A221 and mutants; -, deleted nucleotides. Each sequence was analyzed at least three times, and the results were identical. Consensus positions of replaced nucleotides that confer lincomycin resistance are boxed. Arrows, transcriptional start points (+1) in 1A221 and six mutants (LR 26, 31, 32, 44, 45, and 52) determined by primer extension. The MICs of lincomycin for the wild type and the resistant mutants were determined by the agar dilution method proposed by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Dots, different nucleotides between 168 and 1A221 in the sequenced region.

We defined the 5′ termini of the 2.2- and 0.7-kb transcripts (Fig. 1) by using total RNA at the mid-log phase of growth from 168, 1A221, and six mutants (LR 26, 31, 32, 44, 45, and 52; representatives of each group in Fig. 2) by primer extension analysis as described previously (5). The transcriptional initiation sites (G at +1) in five of the mutants and in 1A221 were identical. In contrast, the product for the deletion mutant, LR 45, was 2 nucleotides shorter than that for 1A221, which had a C residue at the site (Fig. 2). These results indicated that the 5′ termini of the 2.2- and 0.7-kb transcripts are identical and that the distance from −10 to the initiation site in LR 45 is identical to those in 1A221 and the other five mutants. The mutant LR 9 was not examined because it contained a double mutation.

Many multidrug efflux systems contain a characteristic cis-acting regulatory element in the promoter. The inverted repeat· ·· sequence 5′-AATCAAGATAATAGACCAGTCACTATATT· TTTGATT-3′ (dots and boldface characters indicate the mutation sites and the sequence for −10, respectively; inverted-repeat sequences are underlined) is located at the −10 and downstream regions of the promoter. Therefore, LmrA might regulate promoter activity by directly or indirectly binding to this DNA region. If LmrA is involved in the control of lmr transcription by interacting with this region, mutations causing lmr expression should occur at high frequency in the lmrA coding region because lmrA is approximately 20 times longer (546 bp) than the promoter site. However, the lmrA coding region was changed at the termination codon in only one mutant. We then examined the effects of mutations at the −10 region on the transcription activity of the lmr gene. We measured the promoter activity of 168, 1A221, and lincomycin-resistant mutants by in vitro transcription with a reconstructed EσA holoenzyme and DNA fragments containing promoter regions as described previously (3). We found that mutations increased lmr promoter activity 3- to 20-fold over that of 168. Therefore, mutations at one or at both sites also increased lmr promoter activity in vitro, and lmr operon expression cannot be evoked solely by LmrA binding to the promoter regions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan.

We thank N. Foster for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, M., C. M. Borsch, S. S. Taylor, N. Vazquez-Laslop, and A. A. Neyfakh. 1994. A protein that activates expression of a multidrug efflux transporter upon binding the transporter substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 269:28506-28513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aramaki, H., N. Yagi, and M. Suzuki. 1995. Residues important for the function of a multihelical DNA binding domain in the new transcription factor family of Cam and Tet repressors. Protein Eng. 8:1259-1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujita, M., and Y. Sadaie. 1998. Promoter selectivity of the Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase σA and σH holoenzymes. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 124:89-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffith, J. K., M. E. Baker, D. A. Rouch, M. G. Page, R. A. Skurray, I. T. Paulsen, K. F. Chater, S. A. Baldwin, and P. J. Henderson. 1992. Membrane transport proteins: implications of sequence comparisons. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 4:684-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakeshita, H., A. Oguro, R. Amikura, K. Nakamura, and K. Yamane. 2000. Expression of the ftsY gene, encoding a homologue of the alpha subunit of mammalian signal recognition particle receptor, is controlled by different promoters in vegetative and sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 146:2595-2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumano, M., A. Tamakoshi, and K. Yamane. 1997. A 32 kb nucleotide sequence from the region of the lincomycin-resistance gene (22°-25°) of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome and identification of the site of the lin-2 mutation. Microbiology 143:2775-2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lomovskaya. O., K. Lewis, and A. Matin. 1995. EmrR is a negative regulator of the Escherichia coli multidrug resistance pump EmrAB. J. Bacteriol. 177:2328-2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marger, M., and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1993. A major superfamily of transmembrane facilitators that catalyse uniport, symport and antiport. Trends Biochem. Sci. 18:13-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markham, P. N., and A. A. Neyfakh. 2001. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in Gram-positive bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:509-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saier, M. H., Jr., I. T. Paulsen, M. K. Sliwinski, S. S. Pao, R. A. Skurray, and H. Nikaido. 1998. Evolutionary origins of multidrug and drug-specific efflux pumps in bacteria. FASEB J. 12:265-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.