Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Although nearly all elderly Americans are insured through Medicare, there is substantial variation in their use of services, which may influence detection of serious illnesses. We examined outpatient care in the 2 years before breast cancer diagnosis to identify women at high risk for limited care and assess the relationship of the physicians seen and number of visits with stage at diagnosis.

DESIGN

Retrospective cohort study using cancer registry and Medicare claims data.

PATIENTS

Population-based sample of 11,291 women aged ≥67 diagnosed with breast cancer during 1995 to 1996.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Ten percent of women had no visits or saw only physicians other than primary care physicians or medical specialists in the 2 years before diagnosis. Such women were more often unmarried, living in urban areas or areas with low median incomes (all P≥.01). Overall, 11.2% were diagnosed with advanced (stage III/IV) cancer. The adjusted rate was highest among women with no visits (36.2%) or with visits to physicians other than primary care physicians or medical specialists (15.3%) compared to women with visits to either a primary care physician (8.6%) or medical specialist (9.4%) or both (7.8%) (P <.001). The rate of advanced cancer also decreased with increasing number of visits (P <.001).

CONCLUSIONS

Even within this insured population, many elderly women had limited or no outpatient care in the 2 years before breast cancer diagnosis, and these women had a markedly increased risk of advanced-stage diagnosis. These women, many of whom were unmarried and living in poor and urban areas, may benefit from targeted outreach or coverage for preventive care visits.

Keywords: breast cancer, outpatient care, Medicare, mammography

Patients lacking health insurance receive less outpatient care and have worse outcomes than patients with insurance.1 Medicare provides a model for a universal system of health insurance for elderly adults in the United States. Nearly all Americans are eligible for Medicare at age 65, and 95% of Medicare beneficiaries are covered by both Part A (coverage for inpatient hospitalizations, skilled nursing facilities, and hospice) and Part B insurance (coverage for physician services and outpatient care).2 Nevertheless, the use of outpatient services varies substantially among Medicare beneficiaries, and some data suggest considerable underuse of necessary care.3 Moreover, the Medicare benefit prioritizes care for individuals who are ill over those who are well. Such a structure may limit the number of interactions that generally healthy patients have with the health care system.

Routine outpatient care, nevertheless, has an important role in medicine. Patients who have an established relationship with a physician may be more likely to seek care promptly when they develop symptoms, wait less time for an appointment, and have their physician expedite the evaluation of symptoms. Moreover, routine care may be associated with greater receipt of preventive services4,5 and healthier behavior,5,6 and physicians' routine questions may identify problems that patients may not otherwise discuss. Finally, regular visits to a specific physician may promote trusting relationships7 and greater satisfaction,6,8 thereby promoting better communication between patients and their physicians. For these reasons, the provision of regular outpatient care, particularly primary care, may prompt earlier identification of disease, which for many conditions may translate into improved outcomes.

To understand the relationship between outpatient care and identification of serious illness, we examined the association between outpatient visits among Medicare beneficiaries before breast cancer diagnosis and stage of disease at diagnosis. We studied breast cancer because it is the most common cancer diagnosed among women in the United States and the second leading cause of cancer-related death. In addition, an effective screening test is available that can promote early diagnosis. Despite improvements in early detection of breast cancer over the past 30 years, 10% to 12% of elderly women with invasive breast cancer are still diagnosed with stage III or IV disease,9 and the prognosis for these women is poor.

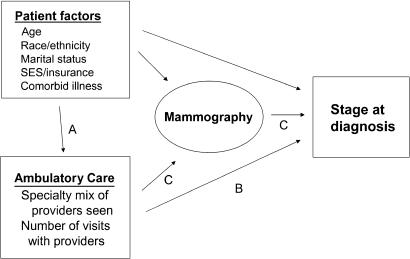

The conceptual framework guiding the study is depicted in Figure 1. Other investigators have examined the relationship between patient factors and mammography use and stage10–14; we focused our analyses on the association of patient characteristics and ambulatory care (pathway A), the association between ambulatory care and stage at diagnosis (pathway B), and whether the association of ambulatory care and stage is mediated by use of mammography (pathway C). Specifically, we first describe the number of visits and types of providers seen by women during the 2 years before diagnosis of breast cancer. Second, because most routine care in the United States is provided by primary care providers and sometimes by medical specialists,15–17 we assessed the characteristics of patients who did not see either type of physician during this time period, but rather saw only other specialists or had no visits (Fig. 1, pathway A), expecting that this group might be at particularly high risk of advanced-stage diagnosis. Third, we assessed the associations of both the providers seen and number of visits with cancer stage at diagnosis (Fig. 1, pathway B). Finally, we examined whether these associations were mediated by use of mammography (Fig. 1, pathway C). We hypothesized that women with fewer visits and those who did not see a primary care provider would be more often diagnosed at later stage, and we believed that much of these differences would be explained by differences in use of mammography.

FIGURE 1.

Model of patient and provider factors associated with stage at diagnosis.

METHODS

Data

We used Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare data for this analysis.18 The SEER program of the National Cancer Institute collects data from 11 population-based cancer registries covering approximately 14% of the U.S. population.19 SEER collects information on month and year of diagnosis, cancer site, histological type, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage,20 and patient demographics. Since 1991, the SEER data have been merged with Medicare administrative data, linking files for more than 94% of SEER registry cases diagnosed at age 65 or older.18 The Medicare data used in this study included claims for outpatient facility services, physicians' services, and inpatient services.

Sample

We selected women with a first diagnosis of breast cancer in 1995 or 1996 who were at least 67 years old at the time of their breast cancer diagnosis and enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B from 2 years before diagnosis through the date of diagnosis (N =17,737). We studied patients diagnosed in 1995 or 1996 because more recent data were not available at the time the study was conducted. We excluded 3,908 women who were enrolled in an HMO at any time during the 2 years before diagnosis (due to incomplete claims), 170 women whose diagnosis was reported by autopsy or death certificate, 54 patients with histologies suggesting a nonprimary breast cancer, 378 nursing home residents, and 26 women whose month of diagnosis was unknown. Finally, we excluded 375 patients with unknown stage and 1,535 patients with ductal carcinoma in situ(because diagnosis is strongly related to mammography use and the long-term benefits of diagnosis at this very early stage are not yet clear), yielding 11,291 women with stage I–IV breast cancer.

Patient Characteristics

The SEER registries document each patient's age at diagnosis, race, Hispanic ethnicity, marital status, residence in a metropolitan county, and history of other cancer. To measure comorbid illnesses, we calculated Diagnostic Cost Groups (DCGs),21 a risk-adjustment tool used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS, formerly the Health Care Financing Administration [HCFA]) to predict disease burden and future costs for Medicare beneficiaries using diagnostic information from both inpatient and ambulatory claims. This tool predicts mortality following admission for myocardial infarction more accurately than the Charlson score.22 We used the Medicare all-encounter model, Release 5.1, to calculate DCGs based on diagnosis codes during the 12-month period that began 14 months before the diagnosis of breast cancer to best characterize patients' comorbid diseases before diagnosis, and categorized these in quartiles. Twelve percent of patients had no diagnosis codes during this time and were classified into the lowest comorbidity quintile. Finally, we used 1990 Census data to obtain information on education and income for patients' zip codes of residence as identified from Medicare files, assigning patients to one of four quartiles based on the income and education distributions within their SEER region of residence.

Providers Seen Before Diagnosis

For each woman, we identified all office visits with physicians (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] codes 99201 to 99205, 99211 to 99215, 99387, 99397, 99401 to 99404, 99241 to 99245) in the physician services and hospital outpatient files. We characterized care during the 2 years before diagnosis, excluding the 2 months immediately preceding diagnosis so as not to include providers participating only in the patient's diagnostic evaluation. We identified the specialty of the physician providing the service using the HCFA specialty code in the physician services claims. For outpatient file claims, we linked the Unique Provider Identification Number (UPIN), a unique, permanent identifier assigned to each provider who cares for Medicare patients, with the Medicare Physician Registry to identify provider specialty.

For each visit, we categorized physicians' specialty as primary care provider (general practitioners, family practitioners, general internists, geriatricians, and obstetrician/gynecologists),23 medical specialists, or other providers. The most frequently visited “other” providers included general surgeons, ophthalmologists, orthopedic surgeons, and other surgical specialists. We then categorized patients into 5 mutually exclusive groups based on the physicians seen: 1) primary care provider, no medical specialist; 2) medical specialist, no primary care provider; 3) primary care provider and medical specialist; 4) other specialist but no primary care provider or medical specialist; and 5) no physician office visits. We also calculated the total number of visits. Patients who saw other specialists in addition to a primary care provider, medical specialist, or both were categorized in the appropriate primary care or medical specialist category because their patterns of care were similar to patients who saw only such providers.

Mammography

We identified mammography in Medicare claims using CPT codes 76090, 76091, and 76092, including screening and diagnostic codes because Medicare claims may not reliably distinguish between screening and diagnostic mammograms.11,24 We classified women as 1) nonusers who had no mammography during the 2 years before diagnosis; 2) occasional users who had 1 mammogram in the 2 years but not in the 3 months before diagnosis; 3) regular users who had at least 2 mammograms that were 10 or more months apart during the 2 years before diagnosis; and 4) peri-diagnosis users who had their only mammogram within 3 months before diagnosis.13

Analyses

Patient Characteristics and Advanced Stage

We used χ2tests to examine bivariate associations between advanced-stage diagnosis (stage III or IV) and patient characteristics, providers seen, number of visits, and mammography use. We next used logistic regression to assess the association between patient and community characteristics and advanced stage. We examined all variables included in Table 1, categorized as shown. An indicator variable for having missing zip code data (<0.5% of patients) was included to allow inclusion of these women in the model.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics Associated with Advanced-stage Breast Cancer Among Medicare Beneficiaries in SEER areas, 1995 to 1996, Unadjusted

| Sample N (%) 11,291 (100%)* | Proportion Diagnosed with Advanced Stage (n =1,266) (11.2%) | P Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| 67 to 70 | 2,439 (22) | 10.0 | |

| 71 to 75 | 3,304 (29) | 10.0 | |

| 76 to 80 | 2,718 (24) | 11.1 | <.001 |

| 81 to 85 | 1,777 (16) | 12.5 | |

| 85+ | 1,053 (9) | 15.9 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 4,589 (41) | 9.1 | |

| Never married, widowed, or divorced | 6,702 (59) | 12.7 | <.001 |

| Residence | |||

| Metropolitan county | 9,436 (84) | 11.3 | .69 |

| Nonmetropolitan county | 1,855 (16) | 10.9 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 10,209 (90) | 10.9 | |

| Black | 670 (6) | 18.4 | <.001 |

| Other | 412 (4) | 8.5 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | |||

| Yes | 356 (3) | 13.2 | .22 |

| No | 10,935 (97) | 11.1 | |

| History of cancer other than breast cancer | |||

| Yes | 976 (9) | 8.8 | .01 |

| No | 10,315 (91) | 11.4 | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 2,959 (26) | 17.2 | |

| Quartile 2 | 2,736 (24) | 9.1 | <.001 |

| Quartile 3 | 2,847 (25) | 8.8 | |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 2,749 (24) | 9.3 | |

| Registry | |||

| Seattle | 1,262 (11) | 13.5 | |

| Hawaii | 221 (2) | 13.1 | |

| Georgia | 642 (6) | 12.8 | |

| Detroit | 1,816 (16) | 12.3 | |

| Connecticut | 1,651 (15) | 11.5 | .008 |

| New Mexico | 448 (4) | 11.4 | |

| San Jose | 551 (5) | 10.3 | |

| San Francisco | 892 (8) | 10.1 | |

| Los Angeles | 1,690 (15) | 10.2 | |

| Iowa | 1,644 (15) | 9.9 | |

| Utah | 474 (4) | 7.6 | |

| Median household income in zip code of residence‡ | |||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 2,869 (26) | 14.2 | |

| Quartile 2 | 2,805 (25) | 10.9 | <.001 |

| Quartile 3 | 2,810 (25) | 9.8 | |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 2,752 (24) | 9.8 | |

| Proportion who are high school graduates in zip code of residence‡ | |||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 2,851 (25) | 14.0 | |

| Quartile 2 | 2,842 (25) | 11.7 | <.001 |

| Quartile 3 | 2,800 (25) | 10.8 | |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 2,743 (24) | 8.2 |

Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

Using the χ2test.

Fifty-five patients were missing information on zip code.

SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

Women with Limited or No Care

We used χ2 tests to assess the association between patient characteristics and limited or no care (no visits with primary care providers or medical specialists), and used logistic regression to identify factors associated with no visits to these providers. The independent variables in the model were the patient- and community-level characteristics described above and categorized as in Table 1.

Effect of Providers Seen and Number of Visits on Advanced-stage Disease

We used logistic regression models to assess the associations of 1) providers seen (categorized as described above) and 2) total number of visits with stage at diagnosis. We adjusted for all of the patient- and community-level variables described for the model above.

To test whether mammography use mediated the associations of care before diagnosis (providers seen and number of visits) with stage at diagnosis, we used logistic regression to assess the association between care before diagnosis and regular mammography. We next added the mammography variables to the model examining the association between care before diagnosis (providers seen and number of visits) and advanced stage and assessed how their inclusion affected the coefficients of interest. Significant relationships between 1) care before diagnosis and advanced stage, 2) care before diagnosis and mammography, and 3) mammography and advanced stage adjusting for care before diagnosis are consistent with mediation by mammography.25,26

For multivariable analyses, we used the likelihood ratio test to assess the overall effect of the multilevel variables, such as provider type or number of visits, on advanced stage at diagnosis. We calculated predicted rates of receiving limited care or of advanced-stage cancer for each category of the independent variables of interest with direct standardization,27,28 allowing the reader to identify absolute percentage point differences in the proportion of women with each outcome by category. Because breast cancer is a commonly diagnosed cancer among Medicare beneficiaries, decreases in the proportion of women diagnosed with advanced stage of as small as 1 to 2 percentage points would be clinically important.

In sensitivity analyses, we repeated all analyses including women with ductal carcinoma in situ, and results were similar. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 8 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The study protocol was approved by the Harvard Medical School Committee on Human Studies. The funding organization had no role in data collection, analysis, or interpretation or approval of the manuscript for publication.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Association with Advanced Stage

Women in the cohort had a mean age of 76 years, 41% were married, and 90% were white (Table 1). Overall, 11.2% of women were diagnosed with advanced-stage breast cancer (stage III or IV). In unadjusted analyses, older women, unmarried women, African-American women, women living in areas with lower median income, and women living in areas with fewer high school graduates had higher rates of advanced-stage disease than other women, and rates of advanced cancer ranged from 7.6% to 13.5% across SEER regions (Table 1). In adjusted analyses, all of these variables except women living in areas with lower median income remained associated with advanced disease. Further adjustment for mammography eliminated the association between age and advanced stage, and reduced the association between education and advanced stage but did not change the relationships with race, marital status, or various regions (data not shown).

Providers Seen and Number of Visits

Patients in the cohort had a median of 10 office visits (interquartile range 5 to 18) in the 2 years before diagnosis (excluding the 2 months before diagnosis). Most patients (84%) had at least 1 visit with a primary care provider and 6% (N =666) saw a medical specialist but no primary care provider. Ten percent of patients had limited or no outpatient care during this 22-month period: 4% (N =468) saw only providers other than primary care providers and medical specialists, and 6% (N =712) had no outpatient visits.

Women with Limited or No Outpatient Care

We next characterized this 10% of the sample who had no outpatient visits with primary care providers or medical specialists. In adjusted analyses, women who were unmarried or living in urban settings, areas with the lowest median household income, areas with the lowest proportion of high school graduates, or several of the SEER regions were more likely than other women to have had limited or no outpatient care in the 2 years before their diagnosis (Table 2). Women with the lowest comorbidity score were also more likely to have limited or no outpatient care. However, our measure of comorbid illness is claims based, and thus women with no outpatient visits were classified in the lowest comorbidity category. Therefore, this association should be interpreted cautiously.

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Limited or No Outpatient Care

| Adjusted Proportion with Limited or No Outpatient Care* | P Value† | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| 67 to 70 | 10.7 | |

| 71 to 75 | 9.5 | |

| 76 to 80 | 10.1 | >.20 |

| 81 to 85 | 9.3 | |

| 85+ | 10.2 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 9.1 | .009 |

| Never married, widowed, or divorced | 10.6 | |

| Residence | ||

| Metropolitan county | 10.4 | .01 |

| Nonmetropolitan county | 8.2 | |

| Race | ||

| White | 10.0 | |

| Black | 10.4 | .20 |

| Other | 8.2 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||

| Yes | 9.3 | .20 |

| No | 10.0 | |

| History of cancer other than breast cancer | ||

| Yes | 10.5 | .08 |

| No | 9.9 | |

| Median household income in zip code of residence‡ | ||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 12.1 | |

| Quartile 2 | 9.6 | .001 |

| Quartile 3 | 8.4 | |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 9.2 | |

| Proportion who are high school graduates in zip code of residence‡ | ||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 11.4 | |

| Quartile 2 | 9.3 | .07 |

| Quartile 3 | 9.5 | |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 9.3 | |

| Registry | ||

| Seattle | 8.4 | |

| Hawaii | 14.3 | |

| Georgia | 8.9 | |

| Detroit | 11.5 | |

| Connecticut | 9.0 | |

| New Mexico | 11.2 | .03 |

| San Jose | 11.1 | |

| San Francisco | 11.0 | |

| Los Angeles | 10.3 | |

| Iowa | 9.4 | |

| Utah | 9.0 | |

| Comorbidity score | ||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 29.4 | |

| Quartile 2 | 5.4 | .001 |

| Quartile 3 | 2.1 | |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 1.9 |

No outpatient care visits with a primary care provider or medical specialist.

Adjusted for all variables in the table; P value using the likelihood ratio test for multilevel categorical variables.

Fifty-five patients are missing information on zip code.

Effect of Mammography, Providers Seen, and Number of Visits on Advanced-stage Disease

A minority of women (31%) had undergone regular mammography in the 2 years before diagnosis, 55% were peri-diagnosis users only, 4% were occasional users, and 10% had no mammography. Regular users were much less likely than other women to be diagnosed with advanced cancer (4.1% vs 9.9% of peri-diagnosis users, 10.9% of occasional users, and 39.2% of nonusers; P <.001).

In unadjusted analyses, women who saw both a primary care provider and a medical specialist were more likely than others to undergo regular mammography and least likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancer (Table 3). Women who did not see a primary care provider or a medical specialist and those who had no office visits were least likely to undergo regular mammography and most likely to be diagnosed with advanced-stage cancer. Women with more visits were also more likely to have regular mammograms and were less often diagnosed with advanced-stage breast cancer (Table 3).

Table 3.

Unadjusted Proportion of Women with Regular Mammography and Proportion Diagnosed with Advanced-stage Breast Cancer Based on Care During the 2 Years Before Diagnosis

| Care in the 2 Years Before Diagnosis* | Sample N(%) 11,291 (100%) | Proportion with Regular Mammography Use, Unadjusted n =3,472 (31%) | P Value† | Proportion Diagnosed with Advanced Stage, Unadjusted n =1,266 (11,2%) | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of providers seen and total number of outpatient visits | |||||

| PCP, no medical specialist | 5,981 (53) | 31.7 | 9.7 | ||

| Medical specialist, no PCP | 666 (6) | 23.7 | 10.8 | ||

| PCP and medical specialist | 3,464 (31) | 39.2 | <.001 | 7.2 | <.001 |

| Other specialist, no PCP or medical specialist | 468 (4) | 9.6 | 21.4 | ||

| No visits | 712 (6) | 2.1 | 37.1 | ||

| 1 to 4 visits | 1,928 (17) | 19.4 | 15.3 | ||

| 5 to 9 visits | 2,646 (23) | 32.0 | <.001 | 9.3 | <.001 |

| 10 to 15 visits | 2,458 (22) | 34.2 | 8.5 | ||

| 16 to 25 visits | 2,240 (20) | 38.2 | 8.2 | ||

| 26+ | 1,307 (12) | 41.3 | 5.4 |

Excluding the 2 months before diagnosis.

Using the χ2test.

PCP, primary care physician.

With adjustment for patient- and community-level characteristics, the types of providers seen and the number of visits in the 2 years before breast cancer diagnosis remained related to stage at diagnosis (both P <.001; Table 4). Women who saw a primary care provider, medical specialist, or both were substantially less likely to be diagnosed with advanced-stage breast cancer than were women who saw only other specialists or who had no outpatient visits. In addition, more visits were associated with fewer advanced-stage cancers. With 216,000 women expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer in 2004,29 a difference in the proportion of women diagnosed with advanced cancer of 1% (over 2,000 women) would be important.

Table 4.

Adjusted Association Between Providers Seen and Number of Visits in the 2 Years Before Diagnosis and Stage at Diagnosis

| Care in the 2 Years Before Daiagnosis* | Adjusted Proportion Diagnosed with Advanced Stage† | P Value | Adjusted Proportion Diagnosed with Advanced Stage, Also Adjusted for Mammography† | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of providers seen and total number of outpatient visits | ||||

| PCP, no medical specialist | 8.6 | 9.4 | ||

| Medical specialist, no PCP | 9.4 | 9.2 | ||

| PCP and medical specialist | 7.8 | <.001 | 8.8 | .01 |

| Other specialist, no PCP or medical specialist | 15.3 | 14.1 | ||

| No visits | 36.2 | 23.2 | ||

| 1 to 4 visits | 14.2 | 13.0 | ||

| 5 to 9 visits | 9.5 | <.001 | 10.0 | <.001 |

| 10 to 15 visits | 8.6 | 9.4 | ||

| 16 to 25 visits | 8.2 | 9.4 | ||

| 26+ | 5.3 | 6.4 | ||

Excluding the 2 months before diagnosis.

Adjusted for age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, marital status, urban residence, history of cancer other than breast cancer, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry, income, education, and comorbidity; P values were calculated using the likelihood ratio test for the overall effect of provider type or number of visits on advanced stage at diagnosis. Predicted probabilities for specialty type were calculated holding number of visits constant at median (10 visits during 22-month period), and those for number of visits holding type of provider constant.

PCP, primary care physician.

The types of providers seen and number of visits were strongly related to mammography (P <.001). Mammography was also strongly associated with earlier stage at diagnosis (P <.001), and adjustment of the model assessing the relationship between types of providers seen and number of visits and stage with mammography reduced the difference between women who had no visits before diagnosis and those who saw both a primary care physician and a medical specialist by one half (from 28 percentage points to 14 percentage points), indicating that mammography is a partial mediator of the relationship between these variables and stage (Table 4).

Despite the strong associations of providers seen and number of visits with advanced stage, these variables did not explain the later diagnosis among nonwhite women, unmarried women, and women in certain regions (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In a large cohort of Medicare beneficiaries with newly diagnosed breast cancer, ambulatory care in the 2 years before diagnosis was strongly related to stage of disease at diagnosis. Ten percent of women had limited or no outpatient care and were at particularly high risk for advanced-stage cancer. These women, who were more often unmarried and residing in poor and urban areas and areas with fewer high school graduates, may benefit from targeted outreach encouraging them to seek care. Such outreach efforts could be conducted using claims data to expand federal programs measuring and tracking the quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries,30,31 similar to efforts by health plans to identify and send reminders to patients needing immunizations.32 Other policy changes, such as Medicare coverage for regular preventive care visits, may also increase the likelihood that relatively healthy women will seek care. In addition to promoting more mammography, which appears to be a mechanism for earlier diagnosis, increased interaction with providers among women with limited care may promote trust and decrease barriers to obtaining care when ill, and may also prompt improved health behaviors. The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 includes coverage for a one-time initial wellness physical exam within 6 months of enrollment in Medicare Part B.33 Although an improvement over no coverage for well visits, this remains short of covering annual or semi-annual visits.

Among women who saw a primary care provider, medical specialist, or both, women who had visits to both were least likely to be diagnosed with advanced-stage cancer, although this difference was eliminated with adjustment for mammography use. Others have postulated that medical specialists may provide a hidden system of primary care,15 particularly for patients with chronic medical conditions.16 We do not know whether the specialist physicians in our sample were providing first-contact, comprehensive, coordinated, or continuous primary care.34–36 However, our finding that visits to specialists are associated with early diagnosis to the same extent as visits to generalists—after accounting for mammography use—suggests that having a usual source of care may be as important to early diagnosis of breast cancer as the particular type of physician providing that care. Targeting such patients for mammography may be as likely to promote earlier-stage diagnosis as policies requiring that all elderly have a generalist physician as their primary care provider.

The total number of outpatient visits before diagnosis was also strongly related to stage of breast cancer at diagnosis and is consistent with other work suggesting that among Medicare beneficiaries, an increase in the number of visits may be associated with a reduction in mortality.37 More visits may provide greater opportunities to ensure that clinical breast exams and mammograms are performed and that evaluation of patients' symptoms is expedited. Patients who know their doctor well may also be more likely to call for an appointment and wait less time to be seen.

Other studies have found age, race, socioeconomic status, and comorbid illness to be associated with stage at diagnosis.38–40 Our data demonstrated similar findings. Adjustment for mammography accounted for the differences by age and education, but accounting for the types of providers seen and number of visits did not change the associations between race or marital status and advanced-stage diagnosis. We also found regional variations in providers seen and stage at diagnosis that were not explained by the patient- and community-level characteristics that we examined. These differences may reflect differential access to care due to factors we could not measure, such as distance to providers, inadequate transportation, supply of physicians, or patients' beliefs and preferences about care.

Our study has several limitations. First, in using administrative data, visits may have been overlooked if services were not covered or bills were not submitted. This includes mammography done as part of community screening efforts, which may not appear in Medicare claims. At the time of this study, Medicare covered only biennial mammography; however, prior research suggests a high correlation between the number of women reporting mammography in surveys and those identified using Medicare claims.12 Second, our method for identifying provider specialty may have misclassified some physicians, particularly those with more than one specialty or practice site. However, we primarily used the HCFA specialty code, which is useful for identifying the specialty of the physician at the time and place that the service was provided.41 Third, although all women were enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B, we have no data about supplemental insurance, which may have influenced the care received.11 Finally, women seeing primary care physicians and medical specialists may have been more health conscious than other women and therefore are more likely to be diagnosed with early stage; alternatively, women who avoid seeking care may also be reluctant to present for care even if they develop symptoms, and therefore are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced stage. However, we included a comorbidity measure designed to identify clinically important illness but not less serious conditions that might be common among healthy utilizers of care.

In summary, we found substantial variation in the number of visits and types of providers seen in the outpatient setting among Medicare beneficiaries in the 2 years before a diagnosis of breast cancer and identified a substantial minority of women with limited or no ambulatory care. More important, the types of providers seen and number of visits were strongly related to stage at diagnosis. Women who had visits with a primary care provider, medical specialist, or both were most likely to be diagnosed with early-stage disease, and women who saw only other specialists or had no visits were at particularly high risk for advanced-stage diagnosis. Even among this insured population, individuals living in poor and urban areas, as well as unmarried women, were at highest risk of limited or no interaction with the health care system. Targeted outreach to patients receiving such limited care and expanding Medicare coverage for preventive care visits may promote earlier diagnosis of breast cancer and other serious illnesses.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a Clinical Scientist Development Award to Dr. Keating from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. This study used the Linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Information Services and the Office of Strategic Planning, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services, Incorporated; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

The authors would like to thank Yang Xu, MS and Laurie M. Meneades, BS for expert programming assistance and David W. Bates, MD, MSc and Barbara J. McNeil, MD, PhD for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Care Without Coverage: Too Little Too Late. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser Family Foundation. The Medicare Program: Medicare at a Glance. Washington, DC: 2004. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/1066-07.cfm. Accessed November 10, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asch SM, Sloss EM, Hogan C, Brook RH, Kravitz RL. Measuring underuse of necessary care among elderly Medicare beneficiaries using inpatient and outpatient claims. JAMA. 2000;284:2325–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flocke SA, Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ. The association of attributes of primary care with the delivery of clinical preventive services. Med Care. 1998;36:AS21–AS30. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199808001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ettner SL. The relationship between continuity of care and the health behaviors of patients: does having a usual physician make a difference? Med Care. 1999;37:547–55. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:213–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mechanic D. Changing medical organization and the erosion of trust. Milbank Q. 1996;74:171–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weyrauch KF. Does continuity of care increase HMO patients' satisfaction with physician performance? J Am Board Fam Pract. 1996;9:31–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973–1999. Bethesda, MD: 2002. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1973_1999/. Accessed June 14, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCI Breast Cancer Screening Consortium. Screening mammography: a missed clinical opportunity? Results of the NCI Breast Cancer Screening Consortium and National Health Interview Survey Studies. JAMA. 1990;264:54–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blustein J. Medicare coverage, supplemental insurance, and the use of mammography by older women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1138–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns RB, McCarthy EP, Freund KM, et al. Variability in mammography use among older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:922–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Coughlin SS, et al. Mammography use helps to explain differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis between older black and white women. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:729–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-9-199805010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Freund KM, et al. Mammography use, breast cancer stage at diagnosis, and survival among older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1226–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aiken LH, Lewis CE, Craig J, Mendenhall RC, Blendon RJ, Rogers DE. The contribution of specialists to the delivery of primary care. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1363–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906143002404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scherger JE. Primary care physicians and specialists as personal physicians:can there be harmony? J Fam Pract. 1998;47:103–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG, Baldwin LM, Chan L, Schneeweiss R. The generalist role of specialty physicians: is there a hidden system of primary care? JAMA. 1998;279:1364–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Mentnech RM, Kessler LG. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Med Care. 1993;31:732–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, et al. The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2000;88:2398–424. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000515)88:10<2398::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 5th ed. New York, NY: Springer Verlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis RP, Pope GC, Iezzoni LI, et al. Diagnosis-based risk adjustment for Medicare capitation payments. Health Care Financ Rev. 1996;17:101–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ash AS, Posner MA, Speckman J, Franco S, Yacht AC, Bramwell L. Using claims data to examine mortality trends following hospitalization for heart attack in Medicare. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1253–62. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns RB, McCarthy EP, Freund KM, et al. Black women receive less mammography even with similar use of primary care. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:173–82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-3-199608010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Randolph WM, Mahnken JD, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. Using Medicare data to estimate the prevalence of breast cancer screening in older women: comparison of different methods to identify screening mammograms. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1643–57. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.10912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baron RM, Kenney DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arora NK, Johnson P, Gustafson DH, McTavish F, Hawkins RP, Pingree S. Barriers to information access, perceived health competence, and psychosocial health outcomes: test of a mediation model in a breast cancer sample. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little RJ. Direct standardization: a tool for teaching linear models for unbalanced data. Am Stat. 1982;36:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leape LL, Hilborne LH, Bell R, Kamberg C, Brook RH. Underuse of cardiac procedures: do women, ethnic minorities, and the uninsured fail to receive needed revascularization? Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:183–92. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-3-199902020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jemal A, Tiwari R, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:8–29. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jencks SF, Cuerdon T, Burwen DR, et al. Quality of medical care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries: a profile at state and national levels. JAMA. 2000;284:1670–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine. Leadership by Example—Coordinating Government Roles in Improving Healthcare Quality. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sisk JE. How are health care organizations using clinical guidelines? Health Aff (Millwood) 1998;17:91–109. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.5.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The Facts About Upcoming New Benefits in Medicare: Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. Publication number CMS-11054. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet. 1994;344:1129–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lichtenberg FR. The effects of Medicare on health care utilization and outcomes. In: Garber AM, editor. Frontiers in Health Policy Research Conference. 5 vol. Washington, DC: 2001. Available at: http://www.nber.org/~confer/2001/fronts01/lichtenberg.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wells BL, Horm JW. Stage at diagnosis in breast cancer: race and socioeconomic factors. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1383–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.10.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayanian JZ, Kohler BA, Abe T, Epstein AM. The relation between health insurance coverage and clinical outcomes among women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:326–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunter CP, Redmond CK, Chen VW, et al. Breast cancer: factors associated with stage at diagnosis in black and white women. Black/White Cancer Survival Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1129–37. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.14.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldwin LM, Adamache W, Klabunde C, Kenward K, Dalhman C, Warren JL. Linking physician characteristics and Medicare claims data: issues in data availability, quality, and measurement. Med Care. 2002;40:IV-82–IV-95. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]