Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To characterize the changes in health status experienced by a multi-ethnic cohort of women during and after pregnancy.

DESIGN

Observational cohort.

SETTING/PARTICIPANTS

Pregnant women from 1 of 6 sites in the San Francisco area (N=1,809).

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Women who agreed to participate were asked to complete a series of telephone surveys that ascertained health status as well as demographic and medical factors. Substantial changes in health status occurred over the course of pregnancy. For example, physical function declined, from a mean score of 95.2 prior to pregnancy to 58.1 during the third trimester (0–100 scale, where 100 represents better health), and improved during the postpartum period (mean score, 90.7). The prevalence of depressive symptoms rose from 11.7% prior to pregnancy to 25.2% during the third trimester, and then declined to 14.2% during the postpartum period. Insufficient money for food or housing and lack of exercise were associated with poor health status before, during, and after pregnancy.

CONCLUSIONS

Women experience substantial changes in health status during and after pregnancy. These data should guide the expectations of women, their health care providers, and public policy.

Keywords: pregnancy, health status, depression

While pregnancy is a common event for reproductive-age women, surprisingly little has been published about the physical and emotional changes that typically occur during pregnancy and the postpartum period.1–3 Better understanding of the changes in health status that occur over the course of pregnancy could help women define their expectations, and provide data to inform public policies related to the health and function of women. For example, three quarters of reproductive-age women are in the work force.4 Over 90% of working women continue to work while pregnant, with the majority working into the month before delivery. Of the 60% of women who return to work within 1 year of the birth of their first child, two thirds are back at work within 3 months.4 Evidence about the health status of women could inform policies related to leave and disability around the time of pregnancy. Finally, better characterization of the physical and emotional changes that typically occur would allow the definition of risk factors for greater or persistent declines in functional status, so that women at risk could be targeted for interventions to promote health and well-being. Because primary care providers provide care for women of reproductive age before, during, and after pregnancy, it is particularly important for them to be aware of the changes in health status that women experience around the time of pregnancy.5,6

Several small studies suggest that the functional status of reproductive-age women is lower during pregnancy and the postpartum period than at other times.1–3,7 A study of 393 Canadian women found that pregnant women had more limitations due to emotional problems, and lower levels of vitality, physical functioning, and social functioning than a sample of nonpregnant women.2 Less is known about changes in health status over the course of pregnancy, and whether there are demographic or medical factors that are associated with greater declines in health status. A sample of 125 white women with normal pregnancies demonstrated significant declines in physical functioning as pregnancy progressed.1 More affluent women had higher general health and mental health scores early in pregnancy than women with a lower income, but these differences diminished over the course of pregnancy.

This work extends prior work by examining the health status of a large cohort of ethnically diverse women. It was conducted to describe changes in the health status of women during and after pregnancy. We examined 4 key domains of health status, including self-rated health, physical function, vitality, and depressive symptoms. We also examined factors that were associated with poor health status during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

METHODS

Sample

Project WISH (Women and Infants Starting Healthy) is a longitudinal cohort of pregnant women who received their prenatal care at a practice or clinic affiliated with 1 of 6 delivery hospitals in the San Francisco Bay area. The delivery sites were chosen to provide socioeconomic and ethnic diversity, and included an urban public hospital, an urban community hospital, a university hospital, and three medical centers within a large group model managed care organization. Women were eligible to participate in Project WISH if they: 1) received prenatal care at one of the practices or clinics associated with these delivery hospitals and planned to deliver at one of these hospitals, 2) were at least 18 years old at the time of recruitment, 3) spoke English, Spanish, or Cantonese, 4) presented for prenatal care at one of the participating facilities before 16 weeks gestational age, and 5) could be contacted by telephone.

Potentially eligible women were sent an informational letter explaining the study and requesting their participation. This mailing included a prestamped, preaddressed “opt-out” postcard that a woman could return if she did not wish to be contacted. If no “opt-out” postcard was returned within 2 weeks of the mailing, attempts were made to contact the woman by telephone. When a woman was reached, verbal informed consent was obtained using a standard script. Women were enrolled between May 2001 and July 2002. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions.

Assessment

Women who agreed to participate were asked to complete 4 telephone surveys: 1) before 20 weeks gestation, 2) 24 to 28 weeks, 3) 32 to 36 weeks, and 4) 8 to 12 weeks postpartum.

During each interview, women were asked to report their health status using 2 of the 8 subscales of the Medical Outcome Study (MOS) Short Form-36 (SF-36): physical function (composed of 10 items), and vitality (4 items).8 Scores for each subscale range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better health status.8 In addition, we measured the standard self-rated health item (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) that is also part of the SF-36 general health perceptions scale. The SF-36 has been used extensively to evaluate health status and has been administered in both Spanish and Cantonese.9–11 During each interview, women were also asked to complete a short-form Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) to screen for depressive symptoms (10 items).12 The CES-D has been used in Spanish.9,13 During the first interview, participants were asked to report their health status during the month before they became pregnant. During subsequent interviews, they were asked to report their health status during the current month.

Other information ascertained in the first interview included age (categorized as less than 35 years or at least 35 years), race/ethnicity (white, Latina, African-American, Asian, other), marital status (married or living with a partner compared with all else), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate or completed some college, at least college graduate), prepregnancy body mass index (BMI; calculated from the woman's height and weight during the month prior to pregnancy and defined as normal if less than 25 kg/m2, overweight if 25 kg/m2to 29.9 kg/m2, and obese if≥30 kg/m2), preexisting medical conditions diagnosed or treated within the past year (anemia, asthma, diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disease, epilepsy, cancer, lung diseases other than asthma, and rheumatologic, kidney, liver, or heart diseases), diagnosis and treatment for depression within the last year, parity (nulliparous vs parous), whether a woman had experienced a time when she had insufficient money to pay for housing or food during the past year, the frequency and duration of exercise during the month prior to pregnancy (none, 2 hours per week or less, more than 2 hours per week), tobacco use before pregnancy, and a history of alcohol dependence (affirmative response to one of four screening questions).14

Additional measures collected during the subsequent interviews during pregnancy were questions about pregnancy-associated symptoms during the prior month (headaches, nausea or vomiting, indigestion, abdominal cramps, low back pain, shortness of breath when exercising or walking hard, trouble sleeping, dizziness, lightheadedness), the frequency and duration of exercise during pregnancy, and whether a woman had experienced a time when she had insufficient money to pay for housing or food during pregnancy. In the postpartum interview, the questions included whether a woman received adequate social support, whether the pregnancy was a singleton or twin, type of delivery (vaginal, forceps or vacuum-assisted, Cesarean section), weight gained since the month prior to pregnancy, treatment of medical conditions during pregnancy or the postpartum period, including those listed above plus pregnancy-associated hypertension, gestational diabetes, placenta previa, preterm labor, and postpartum infections (i.e., mastitis, lung or urinary tract infections, infection of episiotomy or Cesarean section wounds), the frequency and duration of exercise postpartum, and whether a woman had experienced a time when she had insufficient money to pay for housing or food since delivery.

Outcome Variables

We examined 4 outcome measures: poor physical function, poor vitality, poor or fair health, and depressive symptoms. Because many of the women were at the upper limit of the physical function scale prior to pregnancy (i.e., at the ceiling of the scale),15 we chose to model poor function, defined as scoring below the 25th percentile for women of reproductive age from national normative data.8 This represented a physical function score≤85 for the outcome of poor physical function, and a vitality score≤45 for the outcome of poor vitality. The self-rated health item was dichotomized as poor or fair compared with women who rated their health as good, very good, or excellent.16 A woman was considered to have symptoms suggestive of depression if her CES-D score was over 10, the threshold used for this short form.12 Each of these outcomes was examined at 3 points in time: the month prior to pregnancy, late pregnancy (based on data from the third interview for 1,490 women, or from the second interview if the third was not available, as for 156 women), and the postpartum period.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to examine trends in health status over the course of pregnancy and the postpartum period. Three sets of multivariate logistic regression models were examined: health status prior to pregnancy, health status during pregnancy, and postpartum health status. Variables for the multivariate models were selected on the basis of a priorihypotheses or bivariate associations. To incorporate information about change in health status, models for health status during pregnancy and the postpartum period controlled for health status scores from prior time periods. Both the prepregnancy and pregnancy models controlled for gestational age at the time of the interview, and the postpartum model adjusted for the number of days since delivery. Both the pregnancy and the postpartum models adjusted for whether the pregnancy was a singleton or twin gestation.

RESULTS

Response and Retention Rates

Of the 2,854 women who were potentially eligible to participate in this study, 1,809 participated, 1,045 refused (actively or passively), for a response rate of 63%. At the time of the second survey, 1,704 women were still pregnant and planned to deliver at one of the participating sites, and 1,577 (93%) of these women completed the second telephone survey. At the time of the third survey, 1,637 women were still pregnant and planned to deliver at one of the participating sites, of whom 1,490 completed the third survey (91%). Postpartum surveys were available for 1,480 of the 1,657 women who delivered at one of the participating sites (89%). Nonrespondents were more likely (P <.05) than respondents to be Asian (23.9% vs 14.5%), and less likely to be African-American (11.3% vs 18.3%), Latina (30.5% vs 35.3%), or white (20.6% vs 31.6%). Women who completed the postpartum surveys were of similar age and race to the women who initially enrolled in the study. Women who completed the postpartum survey reported similar physical function, vitality, overall health status, and rates of depressive symptoms prior to pregnancy as women who did not complete the postpartum survey.

Characteristics of the Sample

At the time of enrollment, the median age was 30 years (Table 1). This was the first delivery for approximately half the sample. The sample was racially and ethnically diverse. Almost 60% were born in the United States. The majority were married or living with a partner. Sixteen percent of the sample had not finished high school, and 41% had graduated from college. Fifteen percent of women reported that they had insufficient money for food or housing on at least one occasion during the 12 months prior to pregnancy. Twenty-three percent of the sample was classified as overweight prior to pregnancy, and 18% were obese. Twenty-four percent of women reported no exercise during the month prior to pregnancy. While 26% of women reported that they had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime, only 10% of women reported that they had smoked at least 1 cigarette/day during the 3 months prior to pregnancy, and 3% reported cigarette use during pregnancy. Fourteen percent reported a history of alcohol dependence. Six percent of the women had been diagnosed and treated for anemia during the year prior to pregnancy, 6% with asthma, 5% with depression, and 7% with another chronic illness. The current pregnancy was a twin gestation for 1.2% of the sample.

Table 1.

Description of the Sample (N =1,809)

| Median age, y (range) | 30 (18 to 47) |

| Nulliparous, % | 46.6 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |

| Latina | 35.3 |

| White | 31.6 |

| African American | 18.3 |

| Asian | 14.5 |

| Other | 0.4 |

| Born in the United States, % | 58.8 |

| Married or living with partner, % | 87.5 |

| Educational attainment, % | |

| Less than high school | 16.0 |

| High school graduate/some college | 43.3 |

| College graduate | 40.7 |

| Episode of insufficient money for food or housing in the 12 months prior to pregnancy, % | 15.3 |

| BMI prior to pregnancy, % | |

| Normal (BMI<25) | 58.8 |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0 to 29.9) | 22.8 |

| Obese (BMI≥30.0) | 18.4 |

| Exercise during the month before pregnancy, % | |

| None | 23.8 |

| Up to 2 hours per week | 39.0 |

| More than 2 hours per week | 37.2 |

| Cigarette use, % | |

| Ever smoked 100 cigarettes | 26.0 |

| Smoked at least 1 cigarette/day during the 3 months prior to pregnancy | 10.3 |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 2.8 |

| History of alcohol dependence, % | 13.5 |

| During the year prior to pregnancy, diagsnosed and treated for, % | |

| Anemia | 6.1 |

| Asthma | 5.6 |

| Depression | 5.0 |

| Other chronic disease* | 7.1 |

Includes thyroid disease (n =50), nongestational diabetes (n =20), chronic hypertension (n =23), lung diseases other than asthma (n =10), rheumatologic diseases (n =8), epilepsy (n =4), kidney disease (n =17), liver disease (n =4), heart disease (n =5), and cancer (n =5). Diagnoses are not mutually exclusive.

BMI, body mass index.

Health Status Before, During, and After Pregnancy

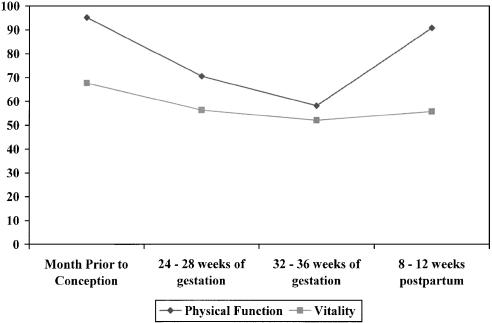

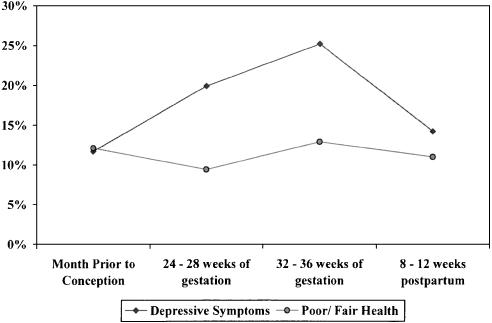

There were substantial changes in health status over the course of pregnancy (Fig. 1). Physical function scores were high prior to conception, declined substantially over the course of pregnancy, and improved postpartum. Vitality scores also declined over the course of pregnancy, but did not approach baseline levels by 3 months postpartum. The prevalence of depressive symptoms rose over the course of pregnancy, and then declined postpartum (Fig. 2). Overall self-reported health status exhibited smaller changes over the course of pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Mean physical function and vitality scores before, during, and after pregnancy. Mean physical function at each time point is different from all other time points (P <.0001). Mean vitality scores at each time point is different from all other time points (P <.0001), except 24 to 28 weeks compared with 8 to 12 weeks postpartum.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of depressive symptoms and poor or fair overall self-rated health before, during, and after pregnancy. Prevalence of depressive symptoms at each time point differs for all other time points (P≤.006). Prevalence of poor or fair health prior to conception significantly different than 24 to 28 weeks (P =.003), 24 to 28 weeks significantly different than 32 to 36 weeks (P <.001), and 32 to 36 weeks different than 8 to 12 weeks postpartum (P =.04).

Factors Associated with Poor Health Status Prior to Pregnancy

Several factors were associated with reporting poor health status during the month prior to conception (Table 2). Women who reported that they had experienced a time when they did not have enough money for food or housing were twice as likely to report fair or poor health (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.49 to 2.98), poor physical function (OR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.37 to 2.88), and depressive symptoms (OR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.61 to 3.29) compared to women who had not experienced this financial deprivation. Obese women were more likely to report poor or fair health, and poor physical function compared to women with a normal BMI. Women who did not exercise prior to pregnancy were more than twice as likely to report each of these outcomes compared to women who exercised at least 2 hours per week. Women who smoked at least 1 cigarette per day during the 3 months prior to conception were more likely to report poor vitality than women who did not smoke. Women who reported a history of alcohol dependence were more likely to report depressive symptoms compared with women who did not have a history of alcohol dependence.

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Poor Health Status During the Month Prior to Pregnancy (N =1,802)

| Poor or Fair Self-rated Health | Poor Physical Function | Poor Vitality | Depressive Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12.1% | 10.7% | 11.0% | 11.7% | |

| Episode of insufficient money for food or housing prior to pregnancy | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Yes | 2.11 (1.49 to 2.98) | 1.99 (1.37 to 2.88) | 1.43 (0.95 to 2.14) | 2.30 (1.61 to 3.29) |

| No | – | – | – | – |

| Body mass index | ||||

| Normal | – | – | – | – |

| Overweight | 1.34 (0.92 to 1.94) | 1.13 (0.76 to 1.70) | 1.12 (0.76 to 1.65) | 0.78 (0.53 to 1.15) |

| Obese | 1.70 (1.16 to 2.48) | 2.13 (1.45 to 3.13) | 1.35 (0.89 to 2.04) | 0.75 (0.49 to 1.13) |

| Exercise prior to pregnancy | ||||

| None | 2.04 (1.41 to 2.97) | 2.30 (1.52 to 3.50) | 2.53 (1.69 to 3.78) | 2.56 (1.72 to 3.82) |

| 2 hours/week or less | 1.12 (0.77 to 1.63) | 1.85 (1.24 to 2.75) | 1.45 (0.98 to 2.14) | 1.69 (1.15 to 2.50) |

| >2 hours/week | – | – | – | – |

| Smoked during the 3 months prior to conception* | 1.04 (0.65 to 1.68) | 0.95 (0.57 to 1.57) | 1.73 (1.11 to 2.68) | 1.50 (0.98 to 2.33) |

| History of alcohol dependence* | 1.55 (1.00 to 2.39) | 1.22 (0.77 to 1.92) | 1.41 (0.93 to 2.15) | 1.93 (1.29 to 2.88) |

All models are adjusted for age, race, marital status, educational attainment, and treatment for asthma, anemia, and other chronic illnesses in the last year, in addition to the factors shown. All models except depressive symptoms are also adjusted for treatment for depression in the last year. Individuals whose self-reported race was categorized as “other” (n=7) are excluded from the adjusted model.

Odds ratios are displayed compared to the reference group of those without the characteristic.

CI, confidence interval.

Factors Associated with Poor Health Status During Pregnancy

Women who reported a time during pregnancy when they did not have enough money for food or housing were twice as likely to report poor or fair health (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.36 to 3.12) and depressive symptoms (OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.22 to 2.62) during pregnancy (Table 3). Lack of exercise during pregnancy was associated with poor or fair self-rated health, poor physical function, poor vitality, and depressive symptoms. No symptoms were associated with the report of poor or fair health. Indigestion was the only symptom associated with poor physical function. All of the symptoms assessed were associated with poor vitality except trouble sleeping, headache, and indigestion. Dizziness, indigestion, shortness of breath, and trouble sleeping were each associated with depressive symptoms. Medical complications during pregnancy were not associated with poor physical function, poor vitality, or depression (not shown). Women with gestational diabetes were more likely to report poor or fair health status (OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.63 to 4.82) than women without gestational diabetes, as were women with preterm labor compared with women who did not experience preterm labor (OR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.43 to 3.40).

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Poor Health Status During Pregnancy (N =1,641)

| Poor or Fair Self-rated Health | Poor Physical Function | Poor Vitality | Depressive Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12.9% | 89.0% | 35.9% | 25.2% | |

| Episode of insufficient money for food or housing during pregnancy | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Yes | 2.06 (1.36 to 3.12) | 1.10 (0.65 to 1.86) | 1.37 (0.96 to 1.96) | 1.79 (1.22 to 2.62) |

| No | – | – | – | – |

| Exercise during pregnancy | ||||

| None | 2.71 (1.70 to 4.32) | 1.83 (1.12 to 2.99) | 1.73 (1.23 to 2.44) | 1.80 (1.22 to 2.64) |

| 2 hours/week or less | 1.13 (0.70 to 1.83) | 1.33 (0.89 to 2.00) | 1.42 (1.03 to 1.94) | 1.21 (0.84 to 1.75) |

| >2 hours/week | – | – | – | – |

| Symptoms reported during pregnancy | ||||

| Dizziness* | 1.40 (0.96 to 2.04) | 1.49 (0.93 to 2.38) | 2.06 (1.57 to 2.71) | 1.39 (1.03 to 1.88) |

| Headache* | 1.29 (0.90 to 1.85) | 1.05 (0.70 to 1.56) | 1.28 (0.98 to 1.67) | 1.24 (0.92 to 1.67) |

| Indigestion* | 1.22 (0.84 to 1.77) | 1.49 (1.04 to 2.13) | 1.28 (0.98 to 1.66) | 1.41 (1.04 to 1.92) |

| Low back pain* | 1.06 (0.69 to 1.61) | 0.98 (0.67 to 1.44) | 1.71 (1.27 to 2.31) | 1.27 (0.90 to 1.78) |

| Shortness of breath* | 1.26 (0.88 to 1.82) | 1.30 (0.89 to 1.89) | 1.32 (1.02 to 1.71) | 1.66 (1.24 to 2.22) |

| Trouble sleeping* | 1.52 (0.93 to 2.47) | 1.42 (0.95 to 2.12) | 1.26 (0.90 to 1.77) | 2.54 (1.61 to 3.99) |

Models are also adjusted for age, race, prior pregnancy health status score, singleton versus twin gestation, pregnancy-associated hypertension, placenta previa, preterm labor, gestational diabetes, and gestational age in addition to the factors shown. Individuals whose self-reported race was categorized as “other” (n =5) are excluded from the adjusted model.

Odds ratios for symptoms compared to reference group of women without that symptom.

CI, confidence interval.

Factors Associated with Poor Health Status 8 to 12 Weeks Postpartum

Women who reported that they had an episode of insufficient money for food or housing during the postpartum period were more likely to report poor or fair health (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.33 to 3.19), poor physical function (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.13 to 2.32), and depressive symptoms (OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.17 to 2.74) compared to women who did not have financial deprivation (Table 4). A perceived lack of social support was associated with each of these adverse health outcomes. Cesarean section was associated with poor or fair health and poor physical function compared to women with a vaginal delivery. Women with a forceps or vacuum-assisted delivery were more likely to report poor vitality compared to women with an uncomplicated vaginal delivery. Physical inactivity postpartum was associated with poor physical function, poor vitality, and depressive symptoms. Women with pregnancy-associated hypertension were more likely to report poor physical function postpartum than women without pregnancy-associated hypertension (OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.02 to 3.38). Medical complications during pregnancy were otherwise not related to health status (not shown).

Table 4.

Factors Associated with Poor Health Status Postpartum (N =1,476)

| Poor or Fair Self-rated Health | Poor Physical Function | Poor Vitality | Depressive Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.0% | 23.8% | 30.8% | 14.2% | |

| Episode of insufficient money for food or housing since delivery | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Yes | 2.06 (1.33 to 3.19) | 1.62 (1.13 to 2.32) | 1.37 (0.93 to 2.00) | 1.79 (1.17 to 2.74) |

| No | – | – | – | – |

| Received inadequate social support | 1.75 (1.09 to 2.81) | 1.56 (1.07 to 2.28) | 2.26 (1.56 to 3.27) | 2.26 (1.47 to 3.47) |

| Received adequate social support | – | – | – | – |

| Type of delivery | ||||

| Cesarean section | 1.76 (1.17 to 2.63) | 2.77 (2.06 to 3.73) | 1.25 (0.93 to 1.68) | 1.09 (0.73 to 1.63) |

| Vacuum or forceps | 1.01 (0.48 to 2.14) | 1.50 (0.93 to 2.42) | 1.63 (1.05 to 2.51) | 1.33 (0.72 to 2.43) |

| Vaginal | – | – | – | – |

| Exercise following delivery | ||||

| None | 1.65 (0.99 to 2.76) | 1.99 (1.38 to 2.87) | 1.92 (1.36 to 2.71) | 1.62 (1.04 to 2.54) |

| 2 hours/week or less | 1.60 (0.97 to 2.65) | 1.44 (1.01 to 2.06) | 1.50 (1.09 to 2.07) | 0.91 (0.58 to 1.43) |

| >2 hours/week | – | – | – | – |

Models are also adjusted for age, race, baby's age in days, gestational age, single versus multiple gestation, weight gained since the month prior to conception, treatment for anemia, high blood pressure, or other chronic conditions during or after pregnancy, pregnancy-associated hypertension, gestational diabetes, placenta previa, preterm labor during pregnancy, postpartum infection, and health status scores during and prior to pregnancy in addition to the factors shown. All models except depressive symptoms also include treatment for depression during or after pregnancy. Individuals whose self-reported race was categorized as “other” (n=4) are excluded from the adjusted model.

CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

This study documents important changes in health status for women over the course of pregnancy and the early postpartum period. While the prepregnancy health status reported by the women in this cohort was similar to or better than normative samples of reproductive-age women,8 limitations in physical function, restrictions in vitality, and the prevalence of depressive symptoms increased over the course of pregnancy. For example, the median physical function scores observed in our study of pregnant women were similar to other studies of people with congestive heart failure, diabetes, and recent myocardial infarction.8 Of the many demographic, medical, and obstetric characteristics we examined, insufficient money for food or housing, and lack of exercise were strongly and consistently associated with poor health status on all of our indicators before, during, and after pregnancy. During pregnancy, symptoms were also an important contributor to poor health status, while in the postpartum period a lack of social support was the most consistent predictor of poor health outcomes. Pregnancy factors, especially Cesarean section, also contributed to poor health status postpartum.

Compared with neonatal health outcomes, maternal health has received considerably less attention.17 While much is known about the physiology of pregnancy,18 less is known about how these physiologic changes affect the experience and function of women. Some have criticized that the health of women is valued only to the extent that it affects the health of the newborn.19 Mortality, the conventional measure of maternal health,20,21 is no longer an adequate measure because of its rarity.20 To better understand maternal health, we need to also understand the interface between a woman's general health and pregnancy. While the majority of reproductive-age women are in good health prior to pregnancy and remain in good health throughout pregnancy, many pregnant women experience important declines in functioning that may persist into the postpartum period.

Patient-reported measures of health status are being widely integrated into clinical care and research and were developed to offer a broader understanding of health than the more traditional physiologic and clinical outcomes.22–27 Although patient-reported measures have been correlated with more conventional outcomes, including physiologic measures28,29 and mortality,26,30,31 these measures extend our understanding of health and well-being. Patient-reported measures of health are sensitive to changes during pregnancy,1–3,7 and thus represent a valuable tool for examining maternal health.

This work is consistent with several smaller studies that suggest that physical function declines during pregnancy.1–3,7 Prior research also suggests that 8% to 20% of pregnant women experience symptoms suggestive of depression during pregnancy.32–36 Using a widely accepted screening instrument, almost a quarter of women in this cohort reported symptoms suggestive of depression during pregnancy. Depression is more common among disadvantaged and minority women.37 Our estimate of the prevalence of depressive symptoms is somewhat higher than the prevalence reported in prior studies,32–35 perhaps because our cohort is more racially and socioeconomically diverse. Our work supports the finding that depressive symptoms during pregnancy may be more common than during the postpartum period.33,38

This study suggests that exercise prior to, during, and after pregnancy is associated with better health status. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology endorses 30 minutes of moderate exercise on most, if not all, days of the week for pregnant women in the absence of medical or obstetric complications.39 There is little empiric work, however, to support the benefits of exercise on health status or outcomes during pregnancy. A recent systematic review concluded that there is insufficient evidence for significant benefits or risks for the mother or fetus related to exercise during pregnancy.40 Future research should investigate whether the relationships observed in our study between physical activity and health status are causal.

While many primary care providers do not provide obstetrical services, they are the health care providers who provide continuity for women before, during, and after pregnancy. Primary care is defined by continuity and sustained relationships.5,6 These results are therefore very relevant to general internists and family physicians who provide care across this continuum. In addition to guiding the expectations of women and their health care providers, a greater understanding of the effect of pregnancy on the health status of women should inform public policies such as work leave policies. Over the past 30 years, the number of women who have entered the work force has increased dramatically.4 Currently, the vast majority of pregnant women continue to work through their third trimester. In the United States, 60% of women who worked during pregnancy return to work within the first year of birth; approximately 5% are back at work within 1 month of delivery, and two thirds return to work by 3 months.4 The Family Medical Leave Act of 1993 mandates up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave for childbearing for many employees.41 Almost 50% of working women take some period of paid, unpaid, or disability leave during pregnancy, while over 80% of these women take leave after the birth of a child.4 Consistent with our findings, data from Sweden, a country with a generous parental benefits program (up to 60 days of compensation prior to delivery, up to a total of 450 days in association with childbirth), suggest that 43% of working women use additional sick leave during pregnancy, most commonly for symptoms of back pain.42 These findings support the need for parental leave policies both during and after pregnancy.

While our cohort provides the most comprehensive assessment of health status during pregnancy to date, our work has several limitations. Because our data are observational, the observed relationships may not be causal. Women were asked during early pregnancy to recall their health status prior to pregnancy, so this initial assessment may be subject to recall bias. It is reassuring, however, that our results are similar to normative data for reproductive-age women.8 Prior work in young adults suggests that prospective measurement of health using the SF-36 demonstrates substantial agreement with retrospective report over a 1-year period, a period longer than the approximately 3-month period of recall in this study.43 We did not examine the health of women beyond the immediate postpartum period. Despite these limitations, our work broadens our understanding of maternal health status and, in particular, identifies risk factors for poorer function.

Women experience substantial declines in physical function and vitality during pregnancy, and the prevalence of depressive symptoms increases. Both lack of exercise and insufficient money for food or housing were consistently associated with poor health status before, during, and after pregnancy. This work underscores the importance of understanding the health of women around the time of pregnancy, independent of an association with infant outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD37389).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hueston WJ, Kasik-Miller S. Changes in functional health status during normal pregnancy. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:209–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otchet F, Carey MS, Adam L. General health and psychological symptom status in pregnancy and the puerperium:what is normal? Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:935–41. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00439-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKee MD, Cunningham M, Jankowski KR, Zayas L. Health-related functional status in pregnancy:relationship to depression and social support in a multi-ethnic population. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:988–93. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith K, Downs B, O'Connell M. Maternity Leave and Employment Patterns: 1961–1995. Vol. P70–79. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2001. Current Population Reports. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. A primary care home for Americans:putting the house in order. JAMA. 2002;288:889–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.7.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haas JS, Meneses V, McCormick MC. Outcomes and health status of socially disadvantaged women during pregnancy. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8:547–53. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware JE., Jr . SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez VM, Stewart A, Ritter PL, Lorig K. Translation and validation of arthritis outcome measures into Spanish. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1429–46. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren XS, Amick B, III, Zhou L, Gandek B. Translation and psychometric evaluation of a Chinese version of the SF-36 Health Survey in the United States. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1129–38. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam CL, Gandek B, Ren XS, Chan MS. Tests of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the Chinese (HK) version of the SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1139–47. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults:evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez-Stable EJ, Marin G, Marin BV, Katz MH. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among Latinos in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:1500–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.12.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bush B, Shaw S, Cleary P, Delbanco TL, Aronson MD. Screening for alcohol abuse using the CAGE questionnaire. Am J Med. 1987;82:231–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36):III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas JS, McCormick MC. Hospital use and health status of women during the 5 years following the birth of a premature, low-birthweight infant. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1151–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.7.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldenberg RL, Rouse DJ. Prevention of premature birth. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:313–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, editors. Obstetrics. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Linvingstone; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenfield A, Maine D. Maternal mortality—a neglected tragedy. Where is the M in MCH? Lancet. 1985;2:83–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koonin LM, MacKay AP, Berg CJ, Atrash HK, Smith JC. Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance—United States, 1987–1990. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1997;46:17–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachs BP, Brown DA, Driscoll SG, et al. Maternal mortality in Massachusetts. Trends and prevention. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:667–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703123161105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarlov AR, Ware JE, Jr, Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Perrin E, Zubkoff M. The Medical Outcomes Study. An application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. JAMA. 1989;262:925–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.7.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calkins DR, Rubenstein LV, Cleary PD, et al. Failure of physicians to recognize functional disability in ambulatory patients. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:451–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-6-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganz PA, Moinpour CM, Pauler DK, et al. Health status and quality of life in patients with early-stage Hodgkin's disease treated on Southwest Oncology Group Study 9133. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3512–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruo B, Rumsfeld JS, Hlatky MA, Liu H, Browner WS, Whooley MA. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life:the Heart and Soul Study. JAMA. 2003;290:215–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rumsfeld JS, MaWhinney S, McCarthy M, Jr, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Participants of the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Processes, Structures, and Outcomes of Care in Cardiac Surgery. JAMA. 1999;281:1298–303. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenman DP, Gelberg L, Liu H, Shapiro MF. Mental health and health-related quality of life among adult Latino primary care patients living in the United States with previous exposure to political violence. JAMA. 2003;290:627–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Permanyer G, Alonso J, Alijarde-Guimera M, Soler-Soler J. Comparison of perceived health status and conventional functional evaluation in stable patients with coronary artery disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:779–86. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee TH, Shammash JB, Ribeiro JP, Hartley LH, Sherwood J, Goldman L. Estimation of maximum oxygen uptake from clinical data:performance of the Specific Activity Scale. Am Heart J. 1988;115(pt 1):203–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCallum J, Shadbolt B, Wang D. Self-rated health and survival:a 7-year follow-up study of Australian elderly. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1100–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowrie EG, Curtin RB, Lepain N, Schatell D. Medical outcomes study short form-36:a consistent and powerful predictor of morbidity and mortality in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:1286–92. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00361-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Hara MW, Zekoski EM, Philipps LH, Wright EJ. Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders:comparison of childbearing and nonchildbearing women. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99:3–15. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ. 2001;323:257–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Georgiopoulos AM, Bryan TL, Yawn BP, Houston MS, Rummans TA, Therneau TM. Population-based screening for postpartum depression. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(pt 1):653–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00543-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pajulo M, Savonlahti E, Sourander A, Helenius H, Piha J. Antenatal depression, substance dependency and social support. J Affect Disord. 2001;65:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FC, Barry KL. Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetrics settings. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:373–80. doi: 10.1089/154099903765448880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dayan J, Creveuil C, Herlicoviez M, et al. Role of anxiety and depression in the onset of spontaneous preterm labor. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:293–301. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ACOG committee opinion. Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Number 267, January 2002. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77:79–81. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kramer MS. Aerobic exercise for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;((2)):CD000180. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000180. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGovern P, Dowd B, Gjerdingen D, Moscovice I, Kochevar L, Murphy S. The determinants of time off work after childbirth. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2000;25:527–64. doi: 10.1215/03616878-25-3-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sydsjo G, Sydsjo A. Newly delivered women's evaluation of personal health status and attitudes towards sickness absence and social benefits. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:104–11. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2002.810203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perneger TV, Etter JF, Rougemont A. Prospective versus retrospective measurement of change in health status:a community based study in Geneva, Switzerland. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51:320–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.51.3.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]