Abstract

OBJECTIVE

This study explores the alignment between physicians' confidence in their diagnoses and the “correctness” of these diagnoses, as a function of clinical experience, and whether subjects were prone to over-or underconfidence.

DESIGN

Prospective, counterbalanced experimental design.

SETTING

Laboratory study conducted under controlled conditions at three academic medical centers.

PARTICIPANTS

Seventy-two senior medical students, 72 senior medical residents, and 72 faculty internists.

INTERVENTION

We created highly detailed, 2-to 4-page synopses of 36 diagnostically challenging medical cases, each with a definitive correct diagnosis. Subjects generated a differential diagnosis for each of 9 assigned cases, and indicated their level of confidence in each diagnosis.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

A differential was considered “correct” if the clinically true diagnosis was listed in that subject's hypothesis list. To assess confidence, subjects rated the likelihood that they would, at the time they generated the differential, seek assistance in reaching a diagnosis. Subjects' confidence and correctness were “mildly” aligned (κ=.314 for all subjects, .285 for faculty, .227 for residents, and .349 for students). Residents were overconfident in 41% of cases where their confidence and correctness were not aligned, whereas faculty were overconfident in 36% of such cases and students in 25%.

CONCLUSIONS

Even experienced clinicians may be unaware of the correctness of their diagnoses at the time they make them. Medical decision support systems, and other interventions designed to reduce medical errors, cannot rely exclusively on clinicians' perceptions of their needs for such support.

Keywords: diagnostic reasoning, clinical decision support, medical errors, clinical judgment, confidence

When making a diagnosis, clinicians combine what they personally know and remember with what they can access or look up. While many decisions will be made based on a clinician's own personal knowledge, others will be informed by knowledge that derives from a range of external sources including printed books and journals, communications with professional colleagues, and, increasingly, a range of computer-based knowledge resources.1 In general, the more routine or familiar the problem, the more likely it is that an experienced clinician can “solve it” and decide what to do based on personal knowledge only. This method of decision making uses a minimum of time, which is a scarce and precious resource in health care practice.

Every practitioner's personal knowledge is, however, incomplete in various ways, and decisions based on incorrect, partial, or outdated personal knowledge can result in errors. A recent landmark study2 has documented that medical errors are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Although these errors have a wide range of origins,3 many are caused by a lack of information or knowledge necessary to appropriately diagnose and treat.4 The exponential growth of biomedical knowledge and shortening half-life of any single item of knowledge both suggest that modern medicine will increasingly depend on external knowledge to support practice and reduce errors.5

Still, the advent of modern information technology has not changed the fundamental nature of human problem solving. Diagnostic and therapeutic decisions, for the foreseeable future, will be made by human clinicians, not machines. What has changed in recent years is the potential for computer-based decision support systems (DSSs) to provide relevant and patient-specific external knowledge at the point of care, assembling this knowledge in a way that complements and enhances what the clinician decision maker already knows.6,7 DSSs can function in many ways, ranging from the generation of alerts and reminders to the critiquing of management plans.8–14 Some DSSs “push” information and advice to clinicians whether they request it or not; others offer no advice until it is specifically requested.

The decision support process presupposes the clinician's openness to the knowledge or advice being offered. Clinicians who believe they are correct, or believe they know all they need to know to reach a decision, will be unmotivated to seek additional knowledge and unreceptive to any knowledge or suggestions a DSS presents to them. The literatures of psychology and medical decision making15–18 address the relationship between these subjective beliefs and objective reality. The well-established psychological bias of “anchoring”15 stipulates that all human decision makers are more loyal to their current ideas, and resistant to changing them, than they objectively should be in light of compelling external evidence.

This study addresses a question central to the potential utility and success of clinical decision support. If clinicians' openness to external advice hinges on their confidence in their assessments based on personal knowledge, how valid are these perceptions? Conceptually, there are 4 possible combinations of objective “correctness” of a diagnosis and subjective confidence in it: 2 in which confidence and correctness are aligned and 2 in which they are not. The ideal condition is an alignment of high confidence in a correct diagnosis. Confidence and correctness can also be aligned in the opposing sense: low confidence in a diagnosis that is incorrect. In this state, clinicians are likely to be open to advice and disposed to consult an external knowledge resource. In the “underconfident” state of nonalignment, a clinician with low confidence in a correct diagnosis will be motivated to seek information that will likely confirm an intent to act correctly. However, it is also possible that a consultation with an external resource can talk a clinician out of a correct assessment.19 The other nonaligned state, of greater concern for quality of care, is high confidence in an incorrect diagnosis. In this “overconfident” state, clinicians may not be open or motivated to seek information that could point to a correct assessment.

This work addresses the following specific questions:

In internal medicine, what is the relationship between clinicians' confidence in their diagnoses and the correctness of these diagnoses?

Does the relationship between confidence and correctness depend on clinicians' levels of experience ranging from medical student to attending physician?

To the extent that confidence and correctness are mismatched, do clinicians tend toward overconfidence or underconfidence, and does this tendency depend on level of clinical experience?

One study similar to this one in design and intent,20 but limited to medical students as subjects, found that students were frequently unconfident about correct diagnostic judgments when classifying abnormal heart rhythms. Our preliminary study of this question has found the relationship between correctness and confidence, across a range of training levels, to be modest at best.21

METHODS

Experimental Design and Dataset

To address these questions, we employed a large dataset originally collected for a study of the impact of decision support systems on the accuracy of clinician diagnoses.19 We developed for this study detailed written synopses of 36 diagnostically challenging cases from patient records at the University of Illinois at Chicago, the University of Michigan, and the University of North Carolina. Each institution contributed 12 cases, each with a firmly established final diagnosis. The 2-to 4-page case synopses were created by three coauthors who are experienced academic internists (PSH, PSF, TMM). The synopses contained comprehensive historical, examination, and diagnostic test information. They did not, however, contain results of definitive tests that would have made the correct diagnosis obvious to most or all clinicians. The cases were divided into 4 approximately equivalent sets balanced by institution, pathophysiology, organ systems, and rated difficulty. Each set, with all patient-and institution-identifying information removed, therefore contained 9 cases, with 3 from each institution.

We then recruited to the study 216 volunteer subjects from these same institutions: 72 fourth-year medical students, 72 second-and third-year internal medicine residents, and 72 general internists with faculty appointments and at least 2 years of postresidency experience (mean, 11 years). Recruitment was balanced so that each institution contributed 24 subjects at each experience level. Each subject was randomly assigned to work the 9 cases comprising 1 of the 4 case sets. Each subject then worked through each of the assigned cases first without, and then with, assistance from an assigned computer-based decision support system. On the first pass through each case, subjects generated a diagnostic hypothesis set with up to 6 items. After generating their diagnostic hypotheses, subjects indicated their perceived confidence in their diagnosis in a manner described below. On the second pass through the case, subjects employed a decision support system to generate diagnostic advice, and again offered a differential diagnosis and confidence ratings. After deleting cases with missing data, the final dataset for this work consisted of 1,911 cases completed by 215 subjects.

Results reported elsewhere19 indicated that the computer-based decision support systems engendered modest but statistically significant improvements in the accuracy of diagnostic hypotheses (overall effect size of .32). The questions addressed by this study, emphasizing the concordance between confidence and correctness under conditions of uncertainty, focus on the first pass through each case where the subjects applied only their personal knowledge to the diagnostic task.

Measures

To assess the correctness of each clinician's diagnostic hypothesis set for each case, we employed a binary score (correct or incorrect). We scored a case as correct if the established diagnosis for that case, or a very closely related disease, appeared anywhere in the subject's hypothesis set. Final scoring decisions, to determine whether a closely related disease should be counted as correct, were made by a panel comprised of coauthors PSF, PSH, and TMM. The measure of clinician confidence was the response to the specific question: “How likely is it that you would seek assistance in establishing a diagnosis for this case?”“Assistance” was not limited to that which might be provided by a computer. After generating their diagnostic hypotheses for each case, subjects responded to this question using an ordinal 1 to 4 response scale with anchor points of 1 representing “unlikely” (indicative of high confidence in their diagnosis) and 4 representing “likely” (indicative of low confidence). Because subjects did not receive feedback, they offered their confidence judgments for each case without any definitive knowledge of whether their diagnoses were, in fact, correct. Because they reflect only the subjects' first pass through each case, these confidence judgments were not confounded by any advice subjects might later have received from the decision support systems.

Analysis

In this study, each data point pairs a subjective confidence assessment on a 4-level ordinal scale with a binary objective correctness score. The structure of this experiment and the resulting data suggested two approaches to analyzing the results. Given that each subject in this study worked 9 cases, and offered confidence ratings on a 1 to 4 scale for each case, interpretations of the meanings of these scale points might be highly consistent for each subject but highly variable across subjects. Our first analytic approach therefore sought to identify an optimal threshold for each subject to distinguish subjective states of “confident” and “unconfident.” This approach addresses the “pooling” problem, identified by Swets and Pickett,22 that would tend to underestimate the magnitude of the relationship between confidence and correctness. Our second analytical approach took the assumption that all subjects made the same subjective interpretation of the confidence scale. This second approach entails a direct analysis of the 2-level by 4-level data with no within-subject thresholding. Qualitatively, the first approach approximates the upper bound on the relationship between confidence and correctness, while the second approach approximates the lower bound.

To implement the first approach, we identified, for each subject, the threshold value along the 1 to 4 scale that maximized the proportion of cases where confidence and correctness were aligned. With reference to Table 1, we sought to find the threshold value that maximized the numbers of cases in the on-diagonal cells. For 58 subjects (27%), we found that maximum alignment was achieved by classifying only ratings of 1 as confident and all other ratings as unconfident; for 105 subjects (49%), maximum alignment was achieved by classifying ratings of 1 or 2 as confident; and for the remaining 52 subjects (24%), maximum alignment was achieved by classifying ratings of 1, 2, or 3 as confident. This finding validated our assumption that subjects varied in their interpretations of the scale points. We then created a dataset for further analysis that consisted, for each case worked by each subject, of a binary correctness score and a binary confidence score calculated using each subject's optimal threshold.

Table 1.

Crosstabulation of Correctness and Confidence for Each Clinical Experience Level and for All Subjects, with Optimal Thresholding for Each Subject

| Experience Level | Correctness of Diagnosis | High | Confidence Low | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | 63 (55 to 71) | 105 (88 to 125) | 168 (146 to 192) | |

| Students | Incorrect | 35 (27 to 43) | 442 (422 to 459) | 477 (453 to 499) |

| Total | 98 (72 to 132) | 547 (513 to 573) | 645 | |

| Correct | 140 (129 to 150) | 141 (124 to 159) | 281 (256 to 306) | |

| Residents | Incorrect | 98 (88 to 109) | 259 (241 to 276) | 357 (332 to 382) |

| Total | 238 (193 to 287) | 400 (351 to 445) | 638 | |

| Correct | 167 (155 to 178) | 144 (128 to 160) | 311 (293 to 339) | |

| Faculty | Incorrect | 80 (69 to 92) | 237 (221 to 253) | 317 (299 to 346) |

| Total | 247 (205 to 300) | 381 (338 to 433) | 628 | |

| Correct | 370 (352 to 388) | 390 (357 to 425) | 760 (713 to 808) | |

| All subjects | Incorrect | 213 (195 to 231) | 938 (903 to 971) | 1,151 (1,103 to 1,198) |

| Total | 583 (527 to 667) | 1,328 (1,246 to 1,405) | 1,911 |

Cells contain counts of cases, with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses.

To address the first research question with the first approach, we computed Kendall's τb and κ coefficients to characterize the relationship between subjects' correctness and confidence levels. We then modeled statistically the proportions of cases correctly diagnosed, as a function of confidence (computed as a binary variable as described above), subjects' level of training (faculty, resident, student), and the interaction of confidence and training level. To address the second question, we modeled the proportions of cases in which confidence and correctness were aligned, as a function of training level. To address the third research question, we focused only on those cases in which confidence and correctness were not aligned. We modeled the proportions of cases in which subjects were overconfident (high confidence in an incorrect diagnosis) as a function of training level.

All statistical models used the Generalized Linear Model (GzdLM) procedure23 assuming diagnostic correctness, alignment, and overconfidence to be distributed as Bernoulli variables with a logit link and used naive empirical covariance estimates24 for the model effects to account for the clustering of cases within subjects. Wald statistics were employed to test the observed results against the null condition. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated by transforming logit scale Wald intervals using naive empirical standard error estimates into percent scale intervals.25 The SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and SAS26 Proc GENMOD (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) software were employed for statistical modeling and data analyses.

Our second approach offers a contrasting strategy to address the first and second research questions. To this end, we computed nonparametric correlation coefficients (Kendall's τb) between the 2-level variable of correctness and the 4 levels of confidence from the original data, without thresholding. We computed separate τb coefficients for subjects at each experience level, and for the sample as a whole. Correlations were computed with case as the unit of analysis after exploratory analyses correcting for the nesting of cases within subjects led to negligible changes in the results.

The power of the inferential statistics employed in this analysis was based on the two-tailed t test, as the tests we performed are analogous to testing differences in means on a logit scale. Because our tests are based on a priori unknown marginal cell counts, we halved the sample size to estimate power. For the analyses addressing research question 1, which use all cases, power is greater than .96 to detect a small to moderate effect of .3 standard deviations at an α level of .05. For analyses addressing research Qquestions 2 and 3, analyses that are based on subsets of cases, the analogous statistical power estimate is greater than .81.

RESULTS

Results with Threshold Correction

Table 1 displays the crosstabulation of correctness of diagnosis and binary levels of confidence (with 95% confidence interval) for all subjects and separately for each clinical experience level, using each subject's optimal threshold to dichotomize the confidence scale. The difficulty of these cases is evident from Table 1, as 760 of 1,911 (40%) were correctly diagnosed by the full set of subjects. Diagnostic accuracy increased monotonically with subjects' clinical experience. The difficulty of the cases is also reflected in the distribution of the confidence ratings, with subjects classified as confident for 583 (31%) of 1,911 cases, after adjustment for varying interpretations of the scale. These confidence levels revealed the same general monotonic relationship with clinical experience. Across the entire sample of subjects, confidence and correctness were aligned for 1,308 of 1,911 cases (68%), corresponding to Kendall's τb=.321 (P <.0001) and a κ value of .314. Alignment was seen in 64% of cases for faculty (τb=.291 [P <.0001]; κ=.285), 63% for residents (τb=.230 [P <.0001]; κ=.227), and 78% for students (τb=.369 [P <.0001]; κ=.349).

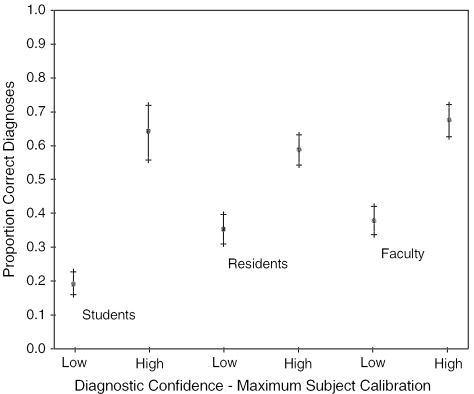

Figure 1 offers a graphical portrayal, for each experience level, of the proportions of correct diagnoses as a function of confidence, with 95% confidence intervals. The relationship between correctness and confidence, at each level, is seen in the differences between these proportions.

FIGURE 1.

Proportions of cases correctly diagnosed at each confidence level, with thresholding to achieve maximum calibration of each subject. Brackets indicate 95% confidence intervals for each proportion.

Wald statistics generated by the statistical model reveal a significant alignment between diagnostic correctness and confidence across all subjects (χ2=199.64, df=1, P <.0001). Significant relationships are also seen between correctness and training level (χ2=20.40, df=2, P <.0001) and in the interaction between confidence and training level (χ2=17.00, df=2, P <.0002). Alignment levels for faculty and residents differ from those of the students (P <.05); and from inspection of Figure 1 it is evident that students' alignment levels are higher than those of faculty or residents.

With reference to the third research question, Table 2 summarizes the case frequencies for which clinicians at each level were correctly confident—where confidence was aligned with correctness—as well as frequencies for the “nonaligned” cases where they were overconfident and underconfident. Students were overconfident in 25% of nonaligned cases, corresponding to 5% of cases they completed. Residents were overconfident in 41% of nonaligned cases, and 15% of cases overall. Faculty physicians were overconfident in 36% of nonaligned cases, and 13% of cases overall.

Table 2.

Breakdown of Under- and Overconfidence for Cases in Which Clinician Confidence and Correctness Are Nonaligned

| Experience Level | Proportion of Cases that Were Nonaligned | Percentage of Nonaligned Cases Reflecting Underconfidence | Percentage of Nonaligned Cases Reflecting Overconfidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Students | 140/645 | 75.0 (65.2 to 82.8) | 25.0 (17.2 to 34.8) |

| Residents | 239/638 | 59.0 (50.7 to 66.8) | 41.0 (33.2 to 49.3) |

| Faculty | 224/628 | 64.3 (55.4 to 72.3) | 35.7 (27.7 to 44.6) |

| All subjects | 603/1911 | 64.7 (59.5 to 69.5) | 35.3 (30.5 to 40.5) |

Parentheses contain 95% confidence intervals.

All subjects were more likely to be underconfident than overconfident (χ2=29.05, P <.0001). Students were found to be more underconfident than residents (Wald statistics: χ2=6.19, df=2, P <.05). All other differences between subjects' experience levels were not significant.

Results Without Threshold Correction

The second approach to analysis yielded Kendall τb measures of association between the binary measure of correctness and the 4-level measure of confidence, computed directly from the study data, without any corrections. For all subjects and cases, we observed τb=.106 (N =1,911 cases; P <.0001). Separately for each level of training, Kendall coefficients are: faculty τb=.103 (n =628; P <.005), residents τb=.041 (n =638; NS), and students τb=.121 (n =645 cases; P <.001). The polarity of the relationship is as would be expected, associating correctness of diagnosis with higher confidence levels. The τb values reported here can be compared with their counterparts, reported above, for the analyses that included threshold correction.

DISCUSSION

The assumption built into the first analytic strategy, that subjects make internally consistent but personally idiosyncratic interpretations of confidence, generates what may be termed upper-bound estimates of alignment between confidence and correctness. Under the assumptions embedded in this analysis, the results of this study indicate that the correctness of clinicians' diagnoses and their perceptions of the correctness of these diagnoses are, at most, moderately aligned. The correctness and confidence of faculty physicians and senior medical residents were aligned about two thirds of the time—and in cases where correctness and confidence were not aligned, these subjects were more likely to be underconfident than overconfident. While faculty subjects demonstrated tendencies toward greater alignment and less frequent overconfidence than residents, these differences were not statistically significant. Students' results were substantially different from those of their more experienced colleagues, as their confidence and correctness were aligned about four fifths of the time and more highly skewed, when nonaligned, toward underconfidence. The alignment between “being correct” and “being confident”—within groups and for all subjects—would be qualitatively characterized as “fair,” as seen by κ coefficients in the range .2 to .4.27

The more conservative second mode of analysis yielded smaller relationships between correctness and confidence, as seen in the τb coefficient for all subjects, which is smaller by a factor of three. For the residents, the relationship between correctness and confidence does not exceed chance expectations when computed without thresholding. Comparison across experience levels reveals the same trend seen in the primary analysis, with students displaying the highest level of alignment.

The greater apparent alignment for the students, under both analytic approaches, may be explained by the difficulty of the cases. The students were probably overmatched by many of these cases, perhaps guessing at diagnoses, and were almost certainly aware that they were overmatched. This is seen in the low proportions of correct diagnoses for students and the low levels of expressed confidence. These skewed distributions would generate alignment between correctness and confidence of 67% by chance alone. While students' alignments exceeded these chance expectations, a better estimate of their concordance between confidence and correctness might be obtained by challenging the students with less difficult cases, making the diagnostic task as difficult for them as it was for the faculty and residents with the cases employed in this study. We do not believe it is valid to conclude from these results that the students are “more aware” than experienced clinicians of when they are right and wrong.

By contrast, residents and faculty correctly diagnosed 44% and 50% of these difficult cases, respectively, and generated distributions of confidence ratings that were less skewed than those of the students. In cases for which these clinicians' correctness and confidence were not aligned, both faculty and residents showed an overall tendency toward underconfidence in their diagnoses. Despite the general tendency toward underconfidence, residents and faculty in this study were overconfident, placing credence in a diagnosis that was in fact incorrect, in 15% (98/938) and 12% (80/928) of cases, respectively. Because these two more experienced groups are directly responsible for patient care, and offered much more accurate diagnoses for these difficult cases, findings for these groups take on a different interpretation and perhaps greater potential significance.

In designing the study, we approached the measurement of “confidence” by grounding it in hypothetical clinical behavior. Rather than asking subjects directly to estimate their confidence levels in either probabilistic or qualitative terms, we asked them for the likelihood of their seeking help in reaching a diagnosis for each case. We considered this measure to be a proxy for “confidence.” Because our intent was to inform the design of decision support systems and medical error reduction efforts generally, we believe that this behavioral approach to assessment of confidence lends validity to our conclusions.

Limitations of this study include restriction of the task to diagnosis. Differences in results may be seen in clinical tasks other than diagnosis, such as determination of appropriate therapy for a problem already diagnosed. The cases, chosen to be very difficult and with definitive findings excluded, certainly generated lower rates of accurate diagnoses than are typically seen in routine clinical practice. Were the cases in this study more routine, this may have affected the measured levels of alignment between confidence and correctness. In addition, this study was conducted in a laboratory setting, using written case synopses, to provide experimental precision and control. While the case synopses contained very large amounts of clinical information, the task environment for these subjects was not the task environment of routine patient care. Clinicians might have been more, or less, confident in their assessments had the cases used in the study been real patients for whom these clinicians were responsible; and in actual practice, physicians may be more likely to consult on difficult cases regardless of their confidence level. While we employed volunteer subjects in this study, the sample sizes at each institution for the resident and faculty groups were large relative to the sizes at each institution of their respective populations, and thus unlikely to be skewed by sampling bias.

The relationships, of “fair” magnitude, between correctness and confidence were seen only after adjusting each subject's confidence ratings to reflect differing interpretations of the confidence scale. The secondary analytic approach, which does not correct individuals' judgments against their own optimal thresholds, results in observed relationships between correctness and confidence that are smaller. Under either set of assumptions, the relationship between confidence and correctness is such that designers of clinical decision support systems cannot assume clinicians to be accurate in their own assessments of when they do and do not require assistance from external knowledge resources.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01-LM-05630 from the National Library of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hersh WR. A world of knowledge at your fingertips: the promise, reality, and future directions of online information retrieval. Acad Med. 1999;74:240–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199903000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates DW, Gawande AA. Error in medicine: what have we learned? Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:763–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leape LL, Bates DW, Cullen DJ, et al. Systems analysis of adverse drug events. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1995;274:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyatt JC. Clinical data systems, part 3: development and evaluation. Lancet. 1994;344:1682–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norman DA. Melding mind and machine. Technol Rev. 1997;100:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chueh H, Barnett GO. “Just in time” clinical information. Acad Med. 1997;72:512–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199706000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt DL, Haynes RB, Hanna SE, Smith K. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1339–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller RA. Medical diagnostic decision support systems—past, present, and future. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;1:8–27. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1994.95236141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans RS, Pestotnik SL, Classen DC, et al. A computer-assisted management program for antibiotics and other antiinfective agents. N Eng J Med. 1998;338:232–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801223380406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonald CJ, Overhage JM, Tierney WM, et al. The Regenstrief Medical Record System: a quarter century experience. Int J Med Inform. 1999;54:225–53. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(99)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner MM, Pankaskie M, Hogan W, et al. Clinical event monitoring at the University of Pittsburgh. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:188–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cimino JJ, Elhanan G, Zeng Q. Supporting infobuttons with terminological knowledge. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:528–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller PL. Building an expert critiquing system: ESSENTIAL-ATTENDING. Methods Inf Med. 1986;25:71–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124–31. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lichtenstein S, Fischhoff B. Do those who know more also know more about how much they know? Organ Behav Hum Perform. 1977;20:159–83. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen-Szalanski JJ, Bushyhead JB. Physicians' use of probabilistic information in a real clinical setting. J Exp Psychol. 1981;7:928–35. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.7.4.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tierney WM, Fitzgerald J, McHenry R, et al. Physicians' estimates of the probability of myocardial infarction in emergency room patients with chest pain. Med Decis Making. 1986;6:12–7. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8600600103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman CP, Elstein AS, Wolf FM, et al. Enhancement of clinicians' diagnostic reasoning by computer-based consultation: a multisite study of 2 systems. JAMA. 1999;282:1851–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.19.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann D. 1993. The relationship between diagnostic accuracy and confidence in medical students. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Atlanta.

- 21.Friedman C, Gatti G, Elstein A, Franz T, Murphy G, Wolf F. 2001. pp. 454–8. Are Clinicians Correct When They Believe They Are Correct? Implications for Medical Decision Support. Proceedings of the Tenth World Congress on Medical Informatics. London; 2000. Medinfo. [PubMed]

- 22.Swets JA, Pickett RM. Evaluation of Diagnostic Systems: Methods from Signal Detection Theory. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Models. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang K, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neter J, Kutner MH, Nachstsheim CJ, Wasserman W. Applied Linear Regression Models. Chicago, IL: Irwin; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 1999. Version 8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]