Abstract

BACKGROUND

In an era of rising health care costs, many Americans experience difficulty paying for needed health care services. With costs expected to continue rising, changes to private insurance plans and public programs aimed at containing costs may have a negative impact on Americans' ability to afford care.

OBJECTIVES

To provide estimates of the number of adults who avoid health care due to cost, and to assess the association of income, functional status, and type of insurance with the extent to which people with health insurance report financial barriers.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Cross-sectional observational study using data from the Commonwealth Fund 2001 Health Care Quality Survey, a nationally representative telephone survey.

PARTICIPANTS

U.S. adults age 18 and older (N=6,722).

MEASURES

Six measures of avoiding health care due to cost, including delaying or not seeking care; not filling prescription medicines; and not following recommended treatment plan.

RESULTS

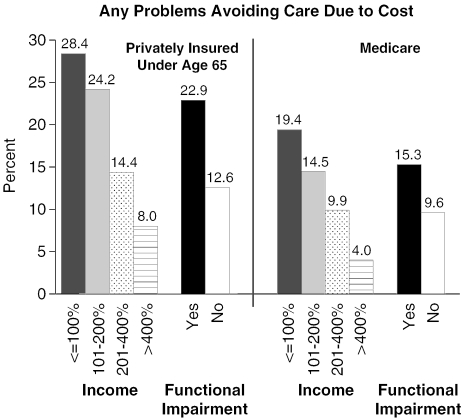

The proportion of Americans with difficulty affording health care varies by income and health insurance coverage. Overall, 16.9% of Americans report at least 1 financial barrier. Among those with private insurance, the poor (28.4%), near poor (24.3%), and those with functional impairments (22.9%) were more likely to report avoiding care due to cost. In multivariate models, the uninsured are more likely (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.7 to 3.0) to have trouble paying for care. Independent of insurance coverage and other demographic characteristics, the poor (OR, 3.6; 95% CI, 2.1 to 4.6), near poor (OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.9 to 3.7), and middle-income (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3 to 2.5) respondents as well as those with functional impairments (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3 to 2.0) are significantly more likely to avoid care due to cost.

CONCLUSIONS

Privately and publicly insured individuals who have low incomes or functional impairments encounter significant financial barriers to care despite having health insurance. Proposals to expand health insurance will need to address these barriers in order to be effective.

Keywords: health care affordability, insurance coverage, low-income populations, functional impairment

In an era of rising health care costs and budget constraints, an increasing number of Americans have difficulty paying for needed health care services. Among the uninsured, finding a provider who offers affordable services is challenging at best, and the wait for an appointment with a provider offering free or reduced-price services can be considerable.1 For those with Medicaid coverage, state budget constraints may affect their eligibility for coverage, the services offered, or their ability to find a provider willing to accept the Medicaid fee schedule.2 Those with Medicare face copayments and bear the rising costs of prescription medications.3 Even the privately insured may face difficulties paying for care with rising premiums, deductibles, and copayments, and private plans that may not cover an adequate amount of their costs to ensure access to quality health care.

One indication of potential difficulties paying for care may come from such changes to private insurance coverage: 68.6% of Americans were covered by private plans in 2003, with 60.4% covered by employer-sponsored plans, representing small but significant declines from 2001 levels of 70.9% and 62.6%, respectively.4,5 While the average cost increase in employer-sponsored benefits was lower in 2003 than in 2002 (10.1% vs 14.7%), employee contributions to premiums rose sharply, deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums increased, copayments increased, and many employers reduced covered services.6 With health care costs increasing and expected to continue at rates greater than 7% annually for the next 5 years,7 such potential changes to private insurance plans and to public programs may negatively impact Americans' ability to afford care.

Medicare spent more than $252 billion in 2002 to pay for health care for individuals ages 65 and over and for certain disabled individuals.8 In addition, many Medicare enrollees ages 65 and over purchase Medigap plans, which are designed to help cover out-of-pocket costs and provide additional insurance coverage. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, which for the first time provides prescription drug benefits under Medicare, is intended to help reduce out-of-pocket drug expenditures for enrollees.9 Its effects may be limited, however, given the sharp increases in prescription drug prices that followed the signing of this act into law.3 In addition, Medicare+Choice—the program's managed care option—continues to shift more costs to enrollees,10 though increased payments to these plans included in recent Medicare reform legislation may affect this trend. On balance, then, the extent to which Medicare beneficiaries are likely to have difficulty paying for care in the future is unclear.

Medicaid generally covers the full cost of covered services or requires only a nominal copayment and precludes providers from “balance billing,”11 thus potentially reducing enrollees' problems paying for care. However, Ku and Nimalendran find that in order to address state budget gaps totaling 78 billion dollars for fiscal year 2004, 34 states have cut their public health insurance program funds. They estimate that 1.2 to 1.6 million low-income people will lose coverage through Medicaid and the State Children's Health Insurance Program as a result of eligibility cuts, increased enrollment barriers, higher premiums, and enrollment freezes. Those who manage to retain public coverage may face a program with reduced provider payments (possibly resulting in fewer participating providers), prescription drug restrictions, or increasing limits on covered services.2

During the economic boom of the 1990s, the uninsurance rate for adults below the age of 65 remained largely stable.12 However, the uninsurance rate has been increasing since 2000, with the growth in the number of uninsured in 2002 representing the largest single-year change since 1987.13 A total of 45.0 million Americans were uninsured in 2003, compared with 43.6 million in 2002 and 41.2 million in 2001.4,5 Coupled with growing charges for health care,14 it is likely that there are more uninsured people having increased difficulty paying for needed care. This is a particular concern, given a substantial body of literature that documents the negative health consequences of being uninsured.15,16

Recently, there have been renewed calls for universal health insurance coverage in the United States.17 While such coverage would help those who are currently uninsured, the extent to which they might continue to have problems paying for care under private or public insurance is unknown. Data from the Centers for Disease Control indicate that 6.8% of adults reported problems paying for care despite having private or public health care coverage.18 In this article, we make use of a unique data set that provides estimates of the number of American adults who avoid health care due to cost and their personal characteristics, including health insurance coverage. We also present information on the extent to which people who have health insurance coverage nonetheless report avoiding health care due to cost concerns. In addition to focusing on income levels, this last analysis emphasizes functional status, as health care avoidance due to cost may have particular health risks for those with functional limitations.

DATA AND METHODS

The Commonwealth Fund 2001 Health Care Quality Survey collected detailed information about experiences with health care from a nationally representative sample of 6,722 adults ages 18 and older living in the continental United States. Data were collected via telephone interviews using random digit dialing in 6 languages. The survey oversampled African-American, Hispanic-American, and Asian-American households, and had an overall response rate of 72.1%. Additional information on both the survey design and methodology is available.19,20

We include the following measures of difficulty paying for health care:

Put off, postponed, or did not seek medical care due to cost in the past 12 months

Did not fill prescription medicine due to cost in the past 12 months

Had difficulty or did not see a needed specialist in the past 2 years because could not afford to

Did not follow the doctor's advice or treatment plan, or did not get a recommended test or see a referred doctor in the past 2 years because it cost too much

Used alternative care (including herbal medicines, acupuncture, chiropractor, traditional healers, and herbalists) in the past 2 years because it is a cheaper way of getting care

Any of the above

This article presents descriptive statistics for these measures, as well as multivariate logistic regressions examining the independent effects of individual characteristics—including age, race/ethnicity, immigrant status, gender, health insurance, income, and education—on the ability to afford care. In addition, we include functional limitations, the extent to which a health problem or disability keeps the individual from participating fully in work, school, or other activities. While data on chronic conditions were available, this measure was highly correlated with functional status, and we include functional status in the model as its reporting by household respondents may be more accurate. Household income is described relative to the 2000 federal poverty line (FPL): ≤100% of the FPL (less than $17,463 per year for a family of 4); 101%–200% of the FPL ($17,464 to $34,926 per year); 201%–400% of the FPL ($34,927 to $69,582 per year); and >400% of the FPL (greater than $69,583 per year). This measure reflects annual household income, household size, and number of dependent children. Because income was collected as a categorical variable, we used the midpoint of each category to calculate relationship to the poverty line. An indicator for missing income (18.9%) was included in the multivariate analyses.

Unless otherwise noted, all comparisons discussed in the text are statistically significant at the .05 level or better. Using variables supplied with the survey data,19 all estimates have been weighted to be nationally representative and standard errors have been corrected for the complex survey design using Stata 7.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Odds ratios have been corrected to better approximate relative risk using Zhang's method.21

RESULTS

Our estimate of the proportion of American adults reporting any problems avoiding health care due to cost (postponing care, not filling prescriptions, not seeing specialists, not complying with doctor's advice, or using alternative care because it cost less) is 16.9% (Table 1). However, the proportion of adults experiencing any one of these problems affording care is considerably smaller, with estimates ranging from 2.1% to 6.8%. We estimate that the number of American adults experiencing any of these problems obtaining health care because of cost is between 47.5 and 51.6 million.

Table 1.

Who Can't Pay for Health Care?

| Characteristic | Postponed Needed Care Due to Cost | Postponed Rx Due to Cost | Had Difficulty/Did Not See Specialist Due to Cost | Noncompliant Due to Cost | Used Alternative Care Due to Cost | Any of These Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Percent (Standard Error) | ||||||

| All | 6.8 (0.5) | 6.1 (0.4) | 2.1 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.4) | 5.6 (0.4) | 16.9 (0.7) |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Private | 4.1 (0.5) | 6.1 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.5) | 13.6 (0.8) |

| Medicare | 3.4 (0.9) | 6.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.5) | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.9) | 11.7 (1.6) |

| Medicaid | 6.6 (2.5) | 6.2 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 6.2 (2.3) | 5.3 (1.9) | 20.0 (3.7) |

| Uninsured | 23.6 (2.1) | 13.7 (1.7) | 10.1 (1.5) | 14.8 (1.7) | 10.7 (1.5) | 37.8(2.3) |

| Other | 6.1 (2.4) | 3.6 (1.8) | 0.5 (0.5) | 6.1 (2.6) | 7.3 (2.6) | 13.8 (3.5) |

| Income relative to the federal poverty line | ||||||

| ≤100% | 16.6 (2.2) | 12.2 (1.9) | 6.9 (1.4) | 10.9 (1.8) | 9.0 (1.6) | 30.9 (2.6) |

| 101%–200% | 10.9 (1.4) | 10.0 (1.3) | 3.8 (0.8) | 9.2 (1.3) | 8.3 (1.2) | 25.5 (1.9) |

| 201%–400% | 5.8 (0.8) | 6.4 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.4) | 5.2 (0.8) | 5.2 (0.8) | 16.3 (1.3) |

| ≥400% | 3.2 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.3) | 2.7 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.6) | 8.5 (1.0) |

| Missing | 4.3 (0.8) | 4.2 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.4) | 4.8 (0.8) | 4.8 (0.9) | 14.2 (1.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 6.8 (0.6) | 5.8 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.3) | 5.4 (0.5) | 5.6 (0.5) | 16.4 (0.9) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 6.1 (1.0) | 8.1 (1.2) | 2.3 (0.7) | 5.9 (1.1) | 3.6 (0.8) | 17.2 (1.6) |

| Hispanic | 8.0 (1.2) | 6.6 (1.1) | 2.9 (0.7) | 7.2 (1.2) | 8.1 (1.3) | 20.6 (1.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 5.3 (1.5) | 1.0 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.3) | 4.2 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.5) | 13.2 (2.2) |

| Other Immigrant | 6.2 (2.1) | 10.6 (2.8) | 4.0 (1.8) | 6.6 (2.2) | 5.3 (1.8) | 17.5 (3.2) |

| U.S. born | 7.2 (0.5) | 6.4 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.5) | 5.3 (0.5) | 16.8 (0.7) |

| Foreign born | 4.5 (0.8) | 4.7 (0.9) | 3.0 (0.7) | 5.8 (1.0) | 7.1 (1.1) | 17.2 (1.5) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 5.0 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.4) | 4.2 (0.6) | 5.3 (0.6) | 13.7 (1.0) |

| Female | 8.3 (0.7) | 8.1 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.4) | 7.0 (0.6) | 5.8 (0.6) | 19.5 (0.9) |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 9.2 (1.4) | 7.7 (1.3) | 4.2 (1.0) | 7.9 (1.3) | 6.9 (1.2) | 21.2 (0.9) |

| High school graduate | 7.0 (0.9) | 6.0 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.4) | 5.7 (0.8) | 5.2 (0.7) | 17.1 (1.2) |

| Some college/tech school | 7.3 (0.9) | 6.6 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.5) | 5.5 (0.8) | 6.2 (0.8) | 17.8 (1.3) |

| College graduate or more | 4.6 (0.7) | 5.2 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.5) | 4.8 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.7) | 13.4 (1.1) |

| Functional impairments | ||||||

| Not at all/very little | 5.7 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.2) | 4.7 (0.4) | 5.6 (0.5) | 14.8 (0.7) |

| Fair amount/great deal | 10.8 (1.3) | 10.7 (1.2) | 4.5 (0.8) | 9.9 (1.2) | 5.6 (0.9) | 24.5 (1.7) |

Estimates of the proportion of Americans avoiding health care due to cost vary by income and health insurance coverage. Uninsured adults are generally the most likely to experience each of the problems described, with nearly 2 in 5 estimated to report at least 1 of these difficulties affording needed health care, and approximately 1 in 4 reporting that they put off, postponed, or did not seek medical care due to cost. While these findings regarding the uninsured may be expected, it is particularly interesting that substantial proportions of Medicaid-covered and privately insured adults also report these problems (20.0% and 13.6%, respectively, estimated to report at least 1 problem paying for care). Similarly, avoiding needed care for any of these reasons is prevalent not only among the poor, but also among adults with family incomes at 101%–400% of the FPL (all groups P<.001 when compared with those with incomes at or above 400% FPL). While one might expect that individuals with less than a high school education would be more likely to avoid health care due to cost than college graduates (P<.001), individuals with a high school education or some college are more likely than college graduates to face such problems as well (P<.05 and P<.01, respectively).

In addition, women are more likely than men to experience any problems affording care (estimates of 19.5% vs 13.7%; P<.001). Few significant racial/ethnic disparities in care are evident, although Hispanics (estimate of 20.6%) are more likely than Asians and whites to experience problems obtaining needed care due to cost (P<.01 and P<.05, respectively).

Many of the findings remain significant in logistic regressions adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (Table 2). After adjusting for income and other personal characteristics, the uninsured are more than twice as likely as the privately insured to report avoiding care due to cost. In contrast, Medicare enrollees' experiences are similar to those of privately insured individuals. In contrast to the descriptive findings, we estimate that individuals with Medicaid coverage are no different from those with private coverage once the regression adjusts for income and other characteristics. However, we find that all individuals with incomes less than 400% of the FPL are more likely to have difficulties than those with higher incomes, with the poorest estimated to be 3.1 times as likely to experience problems obtaining needed care due to cost. None of the racial/ethnic or education differences are statistically significant in the regression.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios from Multivariate Logistic Regression for Having Any Problem Avoiding Care Due to Cost*

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Health insurance | ||

| Private | 1.0 | |

| Medicare | 0.8 | (0.51 to 1.18) |

| Medicaid | 0.9 | (0.53 to 1.52) |

| Uninsured | 2.3 | (1.73 to 2.96)§ |

| Other | 0.9 | (0.46 to 1.61) |

| Income relative to the federal poverty line | ||

| ≥400% | 1.0 | |

| 201%–400% | 1.8 | (1.33 to 2.51)§ |

| 101%–200% | 2.6 | (1.87 to 3.73)§ |

| ≤100% | 3.1 | (2.05 to 4.56)§ |

| Missing | 1.7 | (1.17 to 2.43)‡ |

| Age | 0.99 | (0.98 to 0.998)† |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.0 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.8 | (0.60 to 1.05) |

| Hispanic | 0.9 | (0.65 to 1.23) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.8 | (0.47 to 1.28) |

| Other | 1.0 | (0.58 to 1.54) |

| Immigrant | ||

| U.S. born | 1.0 | |

| Foreign born | 0.8 | (0.62 to 1.15) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.0 | |

| Female | 1.4 | (1.09 to 1.67)‡ |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 0.7 | (0.50 to 1.05) |

| High school graduate | 0.8 | (0.61 to 1.09) |

| Some college/technical school | 1.0 | (0.71 to 1.27) |

| College graduate or more | 1.0 | |

| Functional impairments | ||

| Not at all/very little | 1.0 | |

| Fair amount/great deal | 1.6 | (1.26 to 2.03)§ |

| Number of observations | 6,395 | |

Zhang-corrected odds ratios

P<.05

P<.01

P<.001

Finally, for 2 different insurance groups, Figure 1 shows the proportion of adults avoiding care due to cost by income and the presence or absence of functional impairments. Despite the presence of private coverage, problems obtaining needed care due to cost remain far more common among those below 200% of the FPL and those with functional impairments than among those with higher incomes and those without functional impairments. Similarly, Medicare beneficiaries with incomes below 100% of the FPL are considerably more likely to avoid care due to cost than those with incomes greater than 400% of the FPL. Other comparisons for the Medicare group are not statistically significant, likely due to the comparatively small sample size (726). Other data (not shown) indicate that among Medicaid-insured adults, 25.2% of those with incomes below 100% of the FPL and 17.6% of those with functional impairments report avoiding health care due to cost.

FIGURE 1.

Problems avoiding care due to cost. Medicaid data are not displayed due to the small sample size and the concentration of the Medicaid population in income groups below 200% of the federal poverty line.

DISCUSSION

Using data from a nationally representative survey of American adults, we find that approximately 1 in every 6 adults reports avoiding needed health care due to cost. Some of our findings are encouraging. For example, Medicare enrollees have levels of these problems no greater than the privately insured. Also, while it is problematic that many cannot afford health care, the issue does not appear to be compounded by racial and ethnic disparities. Other findings, however, are cause for concern. Substantial proportions of low-income and functionally impaired individuals with private or public insurance report avoiding needed care due to cost. Such problems among those with functional impairments are particularly alarming, given their potentially greater need for health care; the problems encountered by these individuals may demonstrate the inadequacy of existing benefit structures in the face of significant illness.

We may underestimate the true extent to which American adults avoid needed health care due to cost for several reasons. First, the Commonwealth Fund 2001 Health Care Quality Survey excludes information on children and was administered via telephone, which is likely to disproportionately exclude the poorest households in which individuals may have the most difficulties with the cost of health care. Second, respondents may underreport financial barriers if they perceive a stigma. Third, the survey does not address the issue of providers not suggesting treatment options because they know that the patient cannot afford them. Fourth, low-income persons are more likely to be unaware of chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, or elevated cholesterol and therefore not perceive the need for care.22 Fifth, we were unable to examine differences among subgroups of Medicare beneficiaries associated with supplemental insurance or managed care enrollment.

There are two additional limitations to this study. First, the questions on problems related to paying for health care refer to time periods 1 to 2 years preceding the interview, while the questions on health insurance refer only to the individual's current status at the time of the interview, which may result in some misclassification bias. Second, there is a high rate of missing income data. However, this would only be problematic for the analysis if the distribution of income for those who are missing data is substantially different from those for whom income is known. This issue is further mitigated by the inclusion in the multivariate model of education, race, and insurance status, which are known correlates of income, and of a dummy variable for missing income.

Avoiding needed care is only one potential response to health-related financial difficulties, and there are a number of additional mechanisms not addressed in the survey that individuals may use to compensate when they cannot afford care. For example, individuals or families may choose to not buy food,23 may forgo paying other bills, or may deviate from prescribed treatments. One study found that 22% of poor or near-poor persons ages 65 and over report not filling a prescription, skipping doses, splitting pills, or not taking the medication as directed because of cost.24 Others describe the ways in which Medicare managed care beneficiaries decreased their use of essential medications during gaps in prescription coverage and how chronically ill adults cut back on medications due to cost concerns.25,26 In addition, many individuals facing financial difficulties obtain care but incur substantial amounts of medical debt. For example, nearly half of all uninsured individuals receiving ambulatory care at a safety net facility report being in debt to that facility, and one quarter of these individuals felt that their debts would deter them from seeking care there again.27 As a result, the true extent of Americans' problems paying for medical care will be considerably higher than our estimates of the proportion of adults who avoid needed care due to cost.

Though the health consequences of uninsurance for adults have been well documented,15 much less is known about the health consequences of financial barriers to care among the privately and publicly insured. Advances in prevention, management of chronic illness, treatment of disabling conditions, and pharmacotherapy can result in improved health and functional status and reduce costly catastrophic events, but may increase the mismatch between existing benefit structures and needed care. This mismatch disproportionately impacts low-income and disabled Americans' ability to afford care.

Currently, there are renewed calls for universal health insurance.17 Our findings underscore that insurance alone will not be enough to ensure that people can afford needed care. Even among those with private insurance, more than 1 in every 4 adults with low family incomes and approximately 1 in every 5 adults with functional limitations experiences difficulty obtaining needed care due to cost. Similarly, 1 in every 5 low-income adults with public insurance coverage reports having problems paying for care. Considering the design of coverage benefits and issues of underinsurance for primary, preventive, and chronic care—not just for catastrophic illness—is crucial in the attempt to alleviate Americans' difficulties paying for needed health care.

With the expected high costs of health care resulting from preventable illnesses, such as heart failure from uncontrolled hypertension, these issues take on increased urgency. In addition, as new technology and medications contribute to rising health care costs, they may also contribute to increasing socioeconomic disparities in health care, as there is evidence that the uninsured have less access to these technologies.28 As a nation, we are generally reluctant to engage in health care rationing based on explicit criteria and instead do so implicitly through financial barriers.29 This disproportionately affects both the uninsured and individuals from low-income families with public or private coverage, who are more likely to face substantial health challenges.15,30 Economic equity in access to needed services will be difficult to achieve without both strategies to promote system efficiency and a process for explicit needs-based allocation of services. Making health care affordable for all is a considerable national challenge, but one that must be addressed in order to eliminate socioeconomic disparities in health and ensure that all Americans have access to high-quality medical care when needed.

Acknowledgments

The views in this article are the authors'. No official endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the Department of Health and Human Services is intended or should be inferred. The authors wish to thank David Meyers, William Lawrence, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

References

- 1.Felt-Lisk S, McHugh M, Howell E. Study of Safety Net Provider Capacity to Care for Low-income Uninsured Patients. Final Report submitted to Health Resources and Services Administration; 2001.

- 2.Ku L, Nimalendran S. Losing Out: States Are Cutting 1.2 to 1.6 Million Low-income People from Medicaid, SCHIP and Other State Health Insurance Programs. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2003. Available at: http://www.cbpp.org/12-22-03health.pdf Accessed December 22, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross DJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Raetzman SO. Trends in Manufacturer Prices of Brand Name Prescription Drugs Used by Older Americans—First Quarter 2004 Update. Issue Brief 69. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2004. Available at: http://research.aarp.org/health/ib69_drugprices.pdf Accessed August 23, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Mills RJ. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2003, Current Population Reports P60-226. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2004. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/p60-226.pdf Accessed August 26, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mills RJ, Bhandari S. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2002, Current Population Reports P60-223. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2003. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/p60-223.pdf Accessed December 23, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Mercer Report. Surprise slow-down in health benefit cost increase. Issue 133, March 22, 2004. Mercer Human Resource Consulting. Available at: http://wrg.wmmercer.com Accessed April 4, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Health Care Expenditures Projections Tables. Table 1. National Health Expenditures and Selected Economic Indicators, Levels and Average Annual Percent Change: Selected Calendar Years 1980–2012. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/statistics/nhe/projections-2002/t1.asp Accessed December 24, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Program Benefit Payments, Selected Fiscal Years. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/researchers/pubs/datacompendium/2003/03pg3.pdf Accessed August 31, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strengthening Medicare: A Framework to Modernize and Improve Medicare. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/infocus/medicare/ Accessed December 23, 2003.

- 10.Achman L, Gold M. Medicare+Choice Plans Continue to Shift More Costs to Enrollees. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2003. Available at: http://www.cmwf.org Accessed December 23, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider A, Elias R, Garfield R, Rousseau D, Wachino V. The Medicaid Resource Book. Washington, DC: The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holahan J, Pohl MB. Changes in insurance coverage: 1994–2000 and beyond. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002; Web Exclusive: W162–W171. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Health Insurance Coverage in America: 2002 Update. Washington, DC: The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2003. Available at: http://www.kff.org/uninsured/trends.cfm Accessed December 29, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Authors' tabulation of total health care charges, 1996–2000 using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

- 15.Institute of Medicine. Care Without Coverage: Too Little, Too Late. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine. Health Insurance Is a Family Matter. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiels J, Haught R. Cost and Coverage Analysis of Ten Proposals to Expand Health Insurance Coverage. Falls Church, VA: The Lewin Group; October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Age- and state-specific prevalence estimates of insured and uninsured persons—United States, 1995–1996. MMWR: Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:529–32. [PubMed]

- 19.Princeton Survey Research Associates. Methodology: Survey on Disparities in Health Care Quality: Spring 2001. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Survey Research Associates; February 28, 2002.

- 20.The Commonwealth Fund. 2001 Health Care Quality Survey. Available at: http://www.cmwf.org/surveys/surveys_show.htm?doc_id=228171 Accessed October 7, 2004.

- 21.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;290:1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kersey MA, Beran MS, McGovern PG, Biros MH, Lurie N. The prevalence and effects of hunger in an emergency department patient population. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1109–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. D.C. Health Care Access Survey, 2003: Highlights and Chartpack. October 2003. Available at: http://www.kff.org/minorityhealth/loader.cfm?url=/commonspot/security/getfile.cfm&PageID=23624. Accessed December 30, 2003. [PubMed]

- 25.Tseng CW, Brook RH, Keeler E, Steers WN, Mangione CM. Cost-lowering strategies used by Medicare beneficiaries who exceed drug benefit caps and have a gap in drug coverage. JAMA. 2004;292:952–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piette JD, Heisler M, Wagner TH. Cost-related medication underuse among chronically ill adults. the treatments people forgo, how often, and who is at risk Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1782–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrulis D, Duchon L, Pryor C, Goodman N. Paying for Health Care When You're Uninsured: How Much Support Does the Safety Net Offer? Boston, MA: The Access Project; January 2003. Available at: http://www.accessproject.org/downloads/d_finreport.pdf Accessed December 30, 2003.

- 28.Glied S, Little SE. The uninsured and the benefits of medical progress. Health Aff. 2003;22:210–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.4.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinhardt UE. Rationing health care. what it is, what it is not, and why we cannot avoid it Baxter Health Policy Rev. 1996;2:63–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pamuck E, Makuc D, Heck K, Reuben C, Lochner K. Health, United States, 1998: Socioeconomic Status and Health Chartbook. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1998. PHS 98-1232-1. [Google Scholar]