Abstract

Background

Little guidance is available for health care providers who try to communicate with patients and their families in a culturally sensitive way about end-of-life care.

Objective

To explore the content and structure of end-of-life discussions that would optimize decision making by conducting focus groups with two diverse groups of patients that vary in ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

Design

Six focus groups were conducted; 3 included non-Hispanic white patients recruited from a University hospital (non-Hispanic white groups) and 3 included African-American patients recruited from a municipal hospital (African-American groups). A hypothetical scenario of a dying relative was used to explore preferences for the content and structure of communication.

Participants

Thirty-six non-Hispanic white participants and 34 African-American participants.

Approach

Content analysis of focus group transcripts.

Results

Non-Hispanic white participants were more exclusive when recommending family participants in end-of-life discussions while African-American participants preferred to include more family, friends and spiritual leaders. Requested content varied as non-Hispanic white participants desired more information about medical options and cost implications while African-American participants requested spiritually focused information. Underlying values also differed as non-Hispanic white participants expressed more concern with quality of life while African-American participants tended to value the protection of life at all costs.

Conclusions

The groups differed broadly in their preferences for both the content and structure of end-of-life discussions and on the values that influence those preferences. Further research is necessary to help practitioners engage in culturally sensitive end-of-life discussions with patients and their families by considering varying preferences for the goals of end-of-life care communication.

Keywords: end-of-life, communication, cultural sensitivity, focus groups, ethnicity

Clinician/patient/family communication has repeatedly been identified as an area of weakness in end-of-life care1–3 and the problem is compounded in cross-cultural medical encounters.4,5 Prior research has focused on identifying ethnic variations in end-of-life care preferences. However, understanding patient preferences alone does not necessarily translate into improved communication about end-of-life care. We need a clearer understanding of both the process and content of how patients and their families envision optimal end-of-life communication with their health care providers to help them make informed decisions.

Several studies have found that African Americans prefer more aggressive care at the end of life than non-Hispanic whites. African Americans are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to request life-sustaining therapy such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intensive care unit admissions, artificial ventilation, and tube feeding,6–11 and are less likely to sign advance directives or Do-Not-Resuscitate orders,11–13,16 or to accept hospice care.17 Studies of cultural preferences are often confounded by socioeconomic factors. Multivariate analyses have shown that low socioeconomic status did not consistently predict the absence of Do-Not-Resuscitate orders,18,19 preferences for hospitalization or feeding tube placement,20 or lack of completion of advance directives documents,21 while ethnicity remained a significant predictor for each of these outcomes.

Cultural beliefs about end-of-life care preferences have been studied and consistent themes have been identified. These studies demonstrate that African Americans have higher levels of distrust of the health care system than non-Hispanic whites, and this distrust influences end-of-life decision making.7,13,22–24 Family support, family values, and religious influences have been shown to play a larger role in end-of-life decision making for African Americans than for non-Hispanic whites.22,23,25–27

While data describing cultural differences in preferences for care exist, prior research has not been able to provide adequate guidance to health care workers who participate in end-of-life discussions, especially in cross-cultural communication contexts. Providers lack information about which topics ought to be discussed, how these topics ought to be broached, which health care providers would be best to deliver information, and which family members should participate. To assess the possible range of preferences for the content and structure of end-of-life discussions in patients of different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, we conducted focus groups of African Americans recruited from a municipal health care system and non-Hispanic whites recruited from a University system. The groups differed broadly along cultural and socioeconomic dimensions. Our goal was not to identify generalizable differences attributable to either of these characteristics or to suggest stereotyped responses on the basis of these characteristics. Rather, we were interested in identifying a range of potential cultural and socioeconomic differences to generate hypotheses about how to guide providers to communicate about end-of-life care in a more sensitive fashion.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted 6 focus groups in May 2002 with a total of 70 participants. Three groups included only African-American participants who received their primary care from Denver Health, a municipal health care system with a network of clinics that generally serve low-income, medically indigent clients in Denver, Colorado. The other 3 groups included only non-Hispanic white participants who were recruited from primary care clinics at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center/University of Colorado Hospital, a tertiary, teaching and research institution in Denver. Each focus group included 10–12 participants, and each session lasted approximately 90 minutes. African-American and non-Hispanic white participants were not combined in the focus groups to allow for more open discussion and enable us to discern potential cultural differences. Focus groups were conducted at the clinical sites from which the participants were recruited.

Participants

African-American and non-Hispanic white adults, 50 years old or older, either volunteered or were invited to participate. We selected an older study population to increase the likelihood that participants had first-hand experience addressing end-of-life issues. Participants responded to posters advertising an opportunity to participate in “conversations about end of life” posted in clinic waiting rooms or were asked by their physicians whether they were interested in volunteering for a study about “end-of-life communication.” Participants in this study did not receive any direct payment for participation. All participants provided informed consent in compliance with Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board requirements.

Data Collection

Two researchers attended each focus group: one moderator (W. H. S. or T. R.) whose ethnicity was concordant with participants of the focus group, and a transcriber/facilitator. A case vignette and a structured interview were developed through an iterative process by the study investigators until a vignette was created that seemed to elicit the type of information desired (see Appendix available online). Each focus group was presented with a scenario of a relative, “John,” who was dying of an “incurable” pulmonary disease and was brought to an emergency room with shortness of breath. In the scenario, John had very little time to live unless placed on a ventilator. No diagnosis was specified to minimize disease-specific biases about care preferences. The scenario was pilot tested on patients in both clinical settings to demonstrate face validity and clarity of the scenario. The structured interview included eleven open-ended questions investigating the participants' perceptions of the role of trust, spirituality, family, quality of life, and medical science in the decision-making process as well as the identification of optimal participants in the discussion.

The focus groups were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Transcribed focus group sessions and demographic data obtained by self-report questionnaire comprised the data for analysis. The demographic questionnaire explored participant's age, occupation, education level, and average annual salary. Completing this questionnaire was optional.

Analysis

Transcriptions were evaluated by the study coordinator (W. H. S.) and a research assistant (F. N. H., a social worker) who were trained and supervised in qualitative research by M. K. S. in biweekly sessions throughout the 3 months of analysis. The evaluators read the transcripts independently and, using the method of content analysis, identified broad themes in the data.28 Each transcript was evaluated in turn, and new ideas and themes were presented by each reader after each transcript was analyzed to develop a unified coding scheme. No new themes arose after the fourth transcript from each group was discussed, suggesting near saturation. Codes were applied to each transcript, taking care to note the individual respondents so that multiple occurrences of a particular sentiment by the same participant were only coded once. Each code was discussed by the 2 evaluators until a consensus was reached, with coding conflicts determined by M. K. S. The investigators applied the final coding scheme to each transcript using Atlas Ti software.29

RESULTS

Sample

Six focus groups were conducted, each with 10–12 participants. Three focus groups took place at the University Hospital and included 36 non-Hispanic white participants. The other 3 focus groups took place at a municipal clinic and included 34 African Americans. Over 90% of the non-Hispanic white participants completed demographic questionnaires (see Table 1). The average age of the non-Hispanic white participants was 67 years old; they reported an annual mean income of over $50,000, and, on average, had finished college. Only half of the African-American participants completed the demographic survey. The African-American participants who did complete the survey were slightly younger, averaging just under 60 years old, were mostly high school graduates, and few participants offered income information. We are unable to comment on non-responders to the demographic survey.

Table 1.

Key Characteristics and Differences between the Focus Groups

| Characteristic | Non-Hispanic White Groups University Hospital n=36 | African-American Groups Municipal Hospital n=34 |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Percent of participants who completed demographic questionnaire | 90 | 50 |

| Mean age (years) | 67 | 60 |

| Highest average education | College | High school |

| Annual mean income | $50,000 | (insufficient reporting) |

| Key findings | ||

| Structure of communication | ||

| Preference for including family members in discussions | Exclusive—limited to “closest” members | Inclusive—extending to friends |

| Preference for including professionals in discussions | Specialist consultation | Spiritual assistance |

| Include social workers and nurses | Include social workers and nurses | |

| Content of communication | Quality of life, medical options, costs, symptoms | Spiritual issues |

| Advance directives | Advance directives | |

| Underlying values | Trust in providers | Lack of trust in providers |

| Autonomy | Autonomy | |

| Faith in doctor | Faith in God, prayer heals | |

| Quality of life determines need for care | Miracles are possible, protect life at all cost | |

Coding Results

A total of 141 thematic codes were generated, falling into 19 categories. The codes were assigned a total of 1,594 times to the text, 974 in the non-Hispanic white groups, and 620 in the African-American groups. Codes fell into 3 thematic categories: the structure of end-of-life conversations, the content of these conversations, and the underlying values that participants bring to these conversations.

STRUCTURE OF DISCUSSION

Patient/Family Participants

Non-Hispanic white groups were more exclusive when selecting representatives for the patient in end-of-life discussions, while African-American members were more inclusive. Twenty statements from the non-Hispanic white groups cited the need for the participation of only the “immediate family,” while only one African-American participant communicated this perspective. The African-American members were more likely to suggest that extended family members ought to participate in end-of-life conversations. Five statements in the African-American groups supported participation from the patient's friends, while participants from the non-Hispanic white groups explicitly stated that friends should not participate. Even among family, non-Hispanic white members frequently expressed that some family members are “more trustworthy” or “closer” than others, and that only the “closest” family ought to be permitted to participate.

Health Care Worker Participants

The desire for specialist consultation and spiritual guidance differed between the groups, while views about other health care worker participants were quite similar. Both groups preferred to have their primary care doctor involved in the decision rather than just the Emergency Department (ED) doctor, who might not be familiar with the patient. The non-Hispanic white members were more concerned about calling a “specialist” to help manage the patient than African-American members (11 statements in non-Hispanic whites compared to one among African Americans). Nonetheless, both groups preferred to discuss end-of-life issues with someone they perceived as more sensitive and less technical, with requests in both groups for the participation of nurses and social workers.

Both groups expressed preferences for communication skills and qualities in health care provider partners. Members of both groups agreed that they preferred that their physicians speak honestly, use language that is “understandable” in “lay terms,” and prefer doctors who are “kind.” Listening skills were considered important in both groups. African-American participants were more concerned that doctors were “respectful” and that family members feel “acknowledged.” Several African Americans specified that the doctor should not “rush” or “pressure” them. One African-American participant exemplified these concerns when she said,

There was this doctor in the ER that made me feel like I was nobody. My husband was there and he couldn't talk and she was asking him questions [about his] medications—and then I broke in with several of the medications he was on. [The doctor said] “I would rather [your husband] answer these questions.”

The African-American groups overwhelmingly preferred to have a spiritual leader participate in the end-of-life discussions while non-Hispanic white group members were divided on the topic. Virtually all African-American group members expressed a desire to discuss end-of-life issues with a spiritual leader, and many believed that it is the duty of the health care worker to help organize and participate in the meeting. A typical statement was:

I certainly would like to talk with my pastor because I feel like you could get together and pray and then maybe we could talk to the nurse but my first thing would be to call my pastor and say, “You know I have a crisis—I need your prayers.”

In the non-Hispanic white groups, 14 members stated that the physician should initiate the inclusion of a spiritual leader, while 15 stated that it was not the job of the health care worker to bring up spiritual issues, and 4 explicitly stated that a spiritual advisor would not be helpful in decision making.

CONTENT OF END-OF-LIFE COMMUNICATION

Medical/Science Questions

We found substantial variance between the groups in their stated desire for more information about the relative's medical condition. Non-Hispanic white members expressed a greater preference for knowledge about the relative's prognosis (37 statements), the various therapeutic options (15 statements), and medication choices to alleviate symptoms (11 statements). The non-Hispanic white groups also requested specific definitions to describe the relative's state such as whether the patient was “aware,”“competent,” and whether the illness was “terminal” or “irreversible.” African-American members demonstrated little curiosity about their relative's medical condition or treatment options.

Quality of Life

When guiding end-of-life care for their relative in the proposed scenario, the non-Hispanic white groups were more inquisitive about their relative's quality of life when ill, their state of existence on the ventilator, and the possible outcomes after the crisis subsided. In the non-Hispanic white groups, we found 25 statements addressing their relative's pain and suffering, 10 statements asking whether their relative was experiencing fear, stress, or panic, 10 statements about their relative's consciousness, 5 statements about their relative's ability to care for him/herself, as well as statements about their relative's ability to communicate, laugh, read, listen to music, or spend time with family. These concerns were rarely addressed in the African-American groups, with only 12 statements about the relative's pain and suffering, 5 about the relative's consciousness, and few other statements about quality of life.

Financial and Legal Concerns

The non-Hispanic white participants more frequently raised pragmatic concerns relating to the cost of care. Eleven statements specifically addressed the cost burden to the family of end-of-life care, and many expressed a desire for explicit communication about the costs of care and the level of coverage offered by insurance. One woman said,

I don't want to sound callous … but with the cost of health care—somebody is going to have to pick up these bills. And to leave your family destitute because you lived one more day is an affront to everything I believe.

Several members of the non-Hispanic white groups also expressed concerns about the cost to society of caring for dying patients. One non-Hispanic white group member said, “The former governor [said] old people have an obligation to die and I agree with him.” Only one statement addressed cost in the African-American group, and indicated a different concern. This member suggested that patients may receive limited care if the family cannot afford to pay for the care.

The non-Hispanic white groups also expressed a desire for legal information when making decisions about end-of-life care. Six members requested information about the law's specification of participants in end-of-life care decision making and 5 members inquired about legal obstacles to removing life support once it has been initiated. Five non-Hispanic white group statements pointed toward legal mechanisms to protect patients from receiving poor care, and several suggested that they would litigate if their relative received unsatisfactory care.

Spiritual Content

We found widely varying views about the extent to which spiritual content ought to be included in end-of-life communication. There was an even split among non-Hispanic white group participants about whether health care workers ought to initiate spiritual issues with family members in end-of-life discussions. Several non-Hispanic whites stated that spirituality is simply a method to comfort family members; patients do not benefit, and health care workers could not be sensitive to the many faiths of their patients.

Conversely, the African-American groups overwhelmingly endorsed physician initiation of discussions about the role of spirituality in the decision process. Fourteen statements suggested that physicians ought to contact a spiritual leader for the family (with no dissenting quotations), 4 suggested that the health care worker must partner with the spiritual leader, and 17 specifically identified prayer as an important component of the end-of-life decision process. One participant said,

They worked on my husband most of the night and they got him stabilized. [The doctor] said “Is there anything else I can do for you?” and I said, “Just pray for us.” And she said, “Oh, I do that good.”… She started praying [and] it really touched me.

Advanced Directives

Members of both the African-American and non-Hispanic white groups consistently endorsed the need for communication about end-of-life care for a patient with a chronic illness prior to presentation in the ED. Members of both groups specifically named “living wills” and “advance directives,” and no members of either group expressed the opinion that advance directives were unimportant. African-American participants were more likely to reference the “family meeting” as a means of completing advance directives, while non-Hispanic white participants emphasized the role of the physician to advocate for and initiate communication about advance directives.

UNDERLYING VALUES INFLUENCING END-OF-LIFE CONVERSATIONS

Trust in the Physician and Health Care System

Trust was often raised as a concern in the African-American groups. Thirteen participants from the African-American groups expressed concerns about their ability to trust their physician or the health care system. One participant opined,

If I say I don't want him put on the ventilator, then are you going to push him out the door and get the next patient in?

In comparison, concerns about trust were only raised twice in the non-Hispanic white groups. Compounding their concern about trust, almost half of the African-American participants articulated concern about their physician's inability to predict patient outcomes.

Spiritual Beliefs

The importance of spirituality in end-of-life communication was the most consistent theme in the African-American groups. On 6 occasions, African-American participants expressed the belief that prayer “heals” patients, 17 referred to God as a power that “heals” patients, and 21 articulated the importance of “faith in God” when addressing end-of-life issues. A typical comment was “with a true believer, God can do all things with prayer.” In contrast, the non-Hispanic white groups were much more likely to discuss their “faith” in their physician to make the right decision, and that medicines prescribed will be responsible for “healing.” One non-Hispanic white participant said,

You have to have faith in your doctor … [if not] you damn well better go out and get another one right now.

Non-Hispanic white group participants who asked for spiritual guidance often clarified that it would provide support and not answers:

That spiritual person is for me, for my support in … that decision. But what he tells me is not going to influence the decision I make. What the doctor tells me is going to make the decision.

Who Decides?

Both groups expressed a strong desire for autonomous decision making. Many members of both groups stated that the family must make decisions based on their perceptions of the beliefs and preferences of the patient, and that they ought to be “aware” of the patient's preferences prior to the hospitalization. In addition, many members of the non-Hispanic white groups focused on the burden that family members face when making life or death decisions for their relatives. One example was,

I feel at that point I would be playing God—to make the decision. It would be a very, very, very difficult decision.

Importance of Quality of Life Versus Preservation of Life

Although never asked directly, many members of both groups offered an insight into their perceptions of the relative importance of preserving life at all costs versus preserving quality of life or “a life worth living.” African-American group members often spoke of the possibility of a “miracle,” and 5 stated that a patient must be kept alive indefinitely so that the miracle can take place. One African-American member said, “We want to put him on the machine regardless of how long because [we] believe faith is so strong it will bring them through.” Another added,

If we are in such a rush, we don't know whether he is going to live or die—put him on that machine if that can keep him alive until we can make the decision … I heard where [for] 14 years somebody was unconscious and came back alive and they were talking.”

The non-Hispanic white members were more likely to believe that if their relative had no significant chance of regaining any meaningful quality of life after initiating the ventilator, then the ventilator ought not to be offered. Yet, non-Hispanic white members suggested on multiple occasions that the patient ought to be placed on life support so that the “family can be assembled,” either to “say goodbye” or to provide more time for the family to determine care plans.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore patient preferences for the content and structure of end-of-life discussions, with a focus on understanding cultural differences that could affect end-of-life decision making. We compared the preferences of 2 different ethnic and socioeconomic groups cared for in different practice settings. A variety of themes that were important to participants when describing ideal end-of-life communication were identified and we observed notable differences between the groups (see Table 1). The results of this study serve to confirm some of the differences in cultural preferences and values found elsewhere in the medical literature. In addition, this study offers new insight into how those preferences and values may be addressed when engaging in end-of-life communication, and offers novel directions for further research aimed at enhancing communication with patients and their families.

Several key differences concerning preferred structural components of end-of-life communication were identified between the non-Hispanic white and African-American groups. The non-Hispanic white groups were more exclusive when selecting family members to participate, were more interested in consultation from specialists, and were less interested in participation from spiritual representatives. Differences were also identified in the ideal content of optimal end-of-life discussions. While both groups believed that advance directives are an important feature of end-of-life care and expressed a strong desire to follow the patient's wishes, non-Hispanic white groups expressed a preference for more information about the patient's medical condition, treatment options, and quality of life. Conversely, the African-American groups stressed the importance of spirituality and prayer in decision making, and the need for health care workers to partner with spiritual representatives to improve communication. The central role of spirituality in end-of-life decision making affirmed previous studies about the importance of faith in the healing process among African Americans.30–32

The groups expressed different underlying values that impact the process of end-of-life communication. The African-American groups expressed more concerns about trust in the physician and health care system and emphasized a need to feel respected by health care workers. African-American distrust for the predominantly non-Hispanic white medical system has been described as the legacy of decades of abuse, discrimination, and denial of care that continues with ongoing reports of disparities in the quality and access to health care.33–35 Acknowledging distrust and maintaining a respectful approach to end-of-life discussions may improve communication and facilitate decision making.

The African-American and non-Hispanic white groups expressed differing opinions about the relative importance of protecting quality of life versus the protection of life itself. Several studies support the finding that duration of life is often more valued than quality of life in African Americans.7,36,37 Practitioners may choose to discuss these topics with patients and their families to better understand the values that influence their decision-making strategies and information needs in end-of-life care. Practitioners should also consider how to best communicate when a patient's desire for information and underlying values conflict with the practitioner's perceptions of appropriate care.38

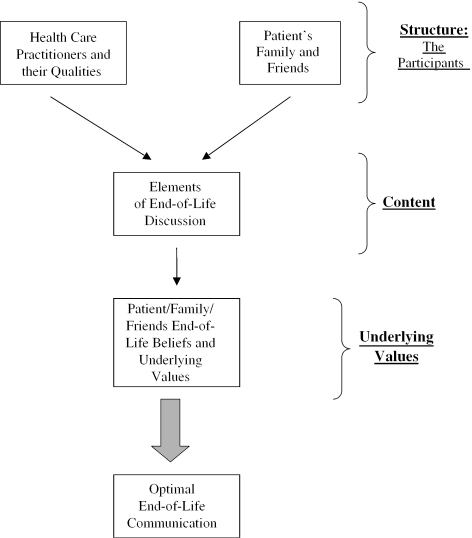

Our study is limited by the fact that we were unable to isolate the effects of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education, or other social characteristics as indicators of communication beliefs. While the groups were assembled on the basis of the members' ethnicity, it is likely that a number of characteristics influenced the differences seen, and it is not possible to attribute differences to ethnicity alone. The results should not be used to apply stereotyped communication blueprints to patients of a specific ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or any other specific characteristics. Rather, the data generated in this study are best used to stimulate dialogue, encourage exploration of communication preferences, and foster further research. Until more is known, providers may consider exploring some of the issues described as a mechanism to better understand their patients' needs. A simplified model identifying some of the key areas that cultural diversity impacted communication preferences is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Possible concerns when engaging in end-of-life communication.

Our study highlights the need to further explore the communication preferences of patients from different social and ethnic groups. The participants in these groups represented only two ethnicities and differed significantly in socio-economic resources. Further study with these and other ethnic groups should be conducted, controlling for socio-economic status, to more fully evaluate ethnic variation in end-of-life communication preferences. Clinicians and researchers should directly ask patients and their families to describe how practitioners might improve the communication process to provide patients with the highest quality end-of-life care.

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material is available for this article online:

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by two sources: (1) A grant from the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center and (2) A grant from the Institute of American Cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles.

We would like to acknowledge the help and commitment of Fran Nedjat Haim, MSW. We would also like to thank Karl Lorenz, MD, MPH and Kenneth Rosenfeld, MD, MPH for their thoughtful assistance on this project.

References

- 1.Baker R, Wu AW, Teno JM, et al. Family satisfaction with end-of-life care in seriously ill hospitalized adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(suppl):S61–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell ES, Collier AC. Why don't patients and physicians talk about end-of-life care? Barriers to communication for patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and their primary care clinicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1690–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanson LC, Danis M, Garrett J. What is wrong with end-of-life care? Opinions of bereaved family members. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1339–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagawa-Singer M, Blackhall LJ. Negotiating cross-cultural issues at the end of life: “you got to go where he lives.”. JAMA. 2001;286:2993–3001. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallenbeck JL. Intercultural differences and communication at the end of life. Primary Care. 2001;28:401–13. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrett JM, Harris RP, Norburn JK, Patrick DL, Danis M. Life-sustaining treatments during terminal illness: who wants what? J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:361–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02600073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caralis PV, Davis B, Wright K, Marcial E. The influence of ethnicity and race on attitudes toward advance directives, life-prolonging treatments, and euthanasia. J Clin Ethics. 1993;4:155–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKinley ED, Garrett JM, Evans AT, Danis M. Differences in end-of-life decision making among black and white ambulatory cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:651–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02600155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien LA, Grisso JA, Maislin G, et al. Nursing home residents' preferences for life-sustaining treatments. JAMA. 1995;274:1775–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodlin SJ, Zhong Z, Lynn J, et al. Factors associated with use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in seriously ill hospitalized adults. JAMA. 1999;282:2333–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien LA, Siegert EA, Grisso JA, et al. Tube feeding preferences among nursing home residents. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:364–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann JC, Wenger NS, Davis RB, et al. Patient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to understand prognoses and preference for outcomes and risks of treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-1-199707010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tulsky JA, Cassileth BR, Bennett CL. The effect of ethnicity on ICU use and DNR orders in hospitalized AIDS patients. J Clin Ethics. 1997;8:150–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepardson LB, Youngner SJ, Speroff T, O'Brien RG, Smyth KA, Rosenthal GE. Variation in the use of do-not-resuscitate orders in patients with stroke. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1841–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenger NS, Pearson ML, Desmond KA, et al. Epidemiology of do-not-resuscitate orders. Disparity by age, diagnosis, gender, race, and functional impairment. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:2056–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eleazer GP, Hornung CA, Egbert CB, et al. The relationship between ethnicity and advance directives in a frail older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:938–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neubauer BJ, Hamilton CL. Racial differences in attitudes toward hospice care. Hosp J. 1990;6:37–48. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1990.11882664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia JA, Romano PS, Chan BK, Kass PH, Robbins JA. Sociodemographic factors and the assignment of do-not-resuscitate orders in patients with acute myocardial infarctions. Med Care. 2000;38:670–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200006000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borum ML, Lynn J, Zhong Z. The effects of patient race on outcomes in seriously ill patients in SUPPORT: an overview of economic impact, medical intervention, and end-of-life decisions. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(suppl 1 5)):S194–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrett JM, Harris RP, Norburn JK, Patrick DL, Danis M. Life sustaining treatments during terminal illness: who wants what? J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:361–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02600073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eleazer GP, Hornung CA, Egbert CB, et al. The relationship between ethnicity and advance directives in a frail older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:938–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klessig J. The effect of values and culture on life-support decisions. West J Med. 1992;157:316–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauser JM, Kleefield SF, Brennan TA, Fischbach RL. Minority populations and advance directives: insights from a focus group methodology. Camb Q Health Ethics. 1997r;6:58–71. doi: 10.1017/s0963180100007611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy ST, Michel V, Palmer JM, Azen SP. Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1779–89. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller B, Campbell RT, Davis L, et al. Minority use of community long-term care services: a comparative analysis. J Gerontol B. Psychol Soc Sci. 1996;51:S70–81. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.2.s70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.High DM. Families' roles in advance directives. Hastings Cent Rep. 1994;24(suppl):S16–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gurland B, Wilder D, Lantigua R, et al. Differences in rates of dementia between ethno-racial groups. In: Martin LG, Soldo BJ, et al., editors. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health of Older Americans. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. pp. 233–69. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willms DG, Best JA, Taylor DW, et al. A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Med Anthropol Q. 1990;4:391–409. [Google Scholar]

- 29.ATLAS Ti [computer software]. Available at http://www.atlasti.de/#map Last accessed 9/4/2002. Berlin, Germany, 2002.

- 30.Waters CM. Understanding and supporting African Americans'perspectives of end-of-life care planning and decision making. Qual Health Res. 2001;11:385–98. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krause N. Common facets of religion, unique facets of religion, and life satisfaction among older African Americans. J Gerontol. Social Sci. 2004;59B:S109–17. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatters LM, Levin JS, Taylor RJ. Antecedents and dimensions of religious involvement among older black adults. J Gerontol. 1992;47:S269–78. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.s269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gamble VN. A legacy of distrust: African Americans and medical research. Am J Prev Med. 1993;9(suppl 6):35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1773–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sehgal A, Galbraith A, Chesney M, Schoenfeld P, Charles G, Lo B. How strictly do dialysis patients want their advance directives followed? JAMA. 1992;267:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKinley ED, Garrett JM, Evans AT, Danis M. Differences in end-of-life decision making among black and white ambulatory cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:651–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02600155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curlin FA, Roach CJ, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lantos JD, Chin MH. When patients choose faith over medicine: physician perspectives on religiously related conflict in the medical encounter. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:88–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]