Abstract

Background

Experts recommend that health care providers (HCPs) collect patients' race/ethnicity, but HCPs worry that this may alienate patients.

Objective

To determine patients' attitudes toward HCPs collecting race/ethnicity data.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Participants

General Internal Medicine patients (n=220).

Measurements

Perceived importance of having HCPs collect race/ethnicity data, their concerns about this, comfort level providing this information, and reactions to 4 statements explaining the rationale for collecting this.

Results

Approximately 80% somewhat or strongly agreed that HCPs should collect information on patients' race/ethnicity. However, 28% had significant discomfort (score 5 or less on 10-point scale) reporting their own race/ethnicity to a clerk, and 58% were somewhat or very concerned that this information could be used to discriminate against patients. Compared with whites, blacks, and Hispanics felt less strongly that HCPs should collect race/ethnicity data from patients (P=.04 for both pairwise comparisons), and blacks were less comfortable reporting their own race/ethnicity than whites (P=.03). Telling patients that this information would be used for monitoring quality of care improved comfort more than telling patients that the data collected (a) was mandated by others, (b) would be used to guide staff hiring and training, and (c) would be used to ensure the patient got the best care possible.

Conclusions

Most patients think HCPs should collect information about race/ethnicity, but many feel uncomfortable giving this information, especially among minorities. Health care providers can increase patients' comfort levels by telling them this will be used to monitor quality of care.

Keywords: race, ethnic groups, data collection

Numerous studies have shown that people of color and racial and ethnic minorities receive unequal treatment by our health care system.1,2 We are now at a crossroads where we must move past merely documenting disparities and embark on initiatives to achieve health care equity. To do this, HCPs must systematically collect information on race, ethnicity, and preferred language to understand their patient population, identify differences in quality of care, and initiate focused programs to eliminated disparities.1–5 Because stereotyping and treatment bias are not necessarily conscious acts,1,2,6 HCPs may deny the possibility that disparities exist until they see data from their own practice. Despite recommendations by a variety of organizations to systematically measure race, ethnicity, and language, current practices are haphazard.7

One reason why hospital administrators are reluctant to routinely ask patients their race and ethnicity is fear this might alienate them,7 especially when faced with a changing and increasingly diverse patient population.8,9 Little objective data are available regarding how patients feel about being asked their race and ethnicity. A proposition in California to ban the collection of race and ethnicity data was defeated, partly because of a perceived need for public health agencies and HCPs to collect this information.9,10 However, in a national survey conducted in 2003, only 34% of respondents favored “congressional legislation which would allow health insurers, health providers, and employers to ask you to voluntarily provide information about your racial or ethnic origin.”11 Support for legislation was higher (54%) among the subsample of participants who were told about health care disparities and the need for further research.

To explore these issues, we surveyed General Internal Medicine patients to determine their perceived importance of having HCPs collect information about patients' race and ethnicity, their concerns about this, their own comfort level providing this information, and their reactions to statements explaining 4 different rationales for collecting this data.

METHODS

Study Site and Population

This study was conducted in the General Internal Medicine clinic of the Northwestern Medical Faculty Foundation in Chicago, Illinois. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University. We included only patients who spoke English fluently because of the low prevalence of patients with limited English proficiency. We approached patients following their visit and asked them to participate. Thus, the study population was a convenience sample and not a random sample. Patients who refused were asked their age, and the research assistant recorded the patient's sex and probable race or ethnicity.

Interview Methods

Participants were first asked to describe their race and/or ethnicity using any terms they wanted. Up to 4 terms were recorded verbatim. We then read 3 statements about how important it was for hospitals, clinics, and physicians' offices to collect information on race/ethnicity, and patients were asked the degree to which they agreed with each statement using a 5-option Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Next, we asked how comfortable the participant would feel if asked by a clerk at a hospital or clinic to report his or her own race/ethnicity and how being asked this information might affect the choice of HCPs in the future. Comfort level was recorded using a 1 to 10 visual scale, with text anchors of “very uncomfortable” at 1 and “very comfortable” at 10. We also determined whether patients would feel more comfortable being asked this information by a nurse or their doctor.

Participants were then read 4 rationales for collecting this information (Appendix): (1) “… review the treatment that all patients receive and make sure everyone gets the highest quality of care.” (“Quality Monitoring”); (2) “Several government agencies recommend we collect information … as part of a national effort to make sure all patients have access to quality health care.” (“Government Recommendation”), (3) “… This will help us decide who to hire, how to train our staff better, and what health information is most helpful for our patients” (“Needs Assessment”), and (4) “… help us make sure you get the best care possible” (“Personal Gain”). We assessed patients' reactions to each statement with 2 questions: (1) “How would hearing this explanation affect how comfortable you would feel about telling a clerk your race or ethnic background?” and (2) “After hearing and reading statement (1, 2, 3, or 4), how comfortable would you be telling a clerk your race or ethnic background on a scale of one to ten?” The order of the 4 statements was randomly varied to eliminate bias. Finally, we asked which of the 4 statements patients preferred.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Stata, version 8.0 (College Station, Tex). Each race and ethnicity term was given a unique identifier as well as a code that mapped to one of the race/ethnicity categories used by the Office of Management and Budget: white, black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (NH/PI), or American Indian/native Alaskan (AI/NA).12 Individuals who reported a single race or ethnicity or who used 2 or more terms that mapped to a single race/ethnicity category (e.g., German and Polish; Cuban and Puerto Rican) were classified as belonging to 1 of the 6 unique categories above. Individuals who used terms from 2 or more categories were classified as multiracial. Differences in responses between whites and other racial/ethnic groups were assessed using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables; we only show our results for whites, blacks, Hispanics, and the multiracial/multiethnic categories because the numbers of participants in the other categories were too small to analyze. We used multivariate linear regression to identify independent predictors of patients' comfort reporting their race/ethnicity and multivariate logistic regression to identify predictors of a patient saying that he or she would be somewhat or much less likely to go to a hospital or clinic that collected information on race/ethnicity.

We compared participants' reactions to the 4 statements designed to increase comfort providing race/ethnicity data by using McNemar's χ2 tests and paired t-tests. Changes in comfort level in response to each statement were calculated, and mean change scores were also compared across the 4 statements. Two-tailed tests were used for all analyses, and a final P-value of .05 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

A total of 220 of 373 (59.0%) patients agreed to participate. The mean age of participants was 44.0 years and 66.7% were female. Most patients (80.9%) had been cared for in the clinic for more than 1 year, and 85.0% had 2 or more visits over the previous year. The racial and ethnic distribution was 41.4% white, 34.1% black/African American, 9.1% Latino/Hispanic, 4.6% Asian, 8.2% multiracial/multiethnic, and 2.7% other or refused. Eligible subjects who refused to participate were more likely to be white (57.5%) and less likely to be Hispanic (5.9%) than participants.

Patients' Attitudes Toward Providers Collecting Race and Ethnicity Information

The majority of participants (79.9%) somewhat or strongly agreed that hospitals and clinics should collect information on race and ethnicity (Table 1), and there was virtually unanimous support for using this information to conduct studies to assess disparities (Table 1). Most participants (66.4%) also agreed that hospitals and clinics should collect this information so they can better train their staff to treat patients of different backgrounds. Although there was strong endorsement of all 3 statements by members of all racial/ethnic groups, blacks, and Hispanics were more likely than whites to disagree that HCPs should collect this information (20.0%, 25.0%, and 8.8%, respectively; P=.04 for both pairwise comparisons of blacks to whites and Hispanics to whites). Blacks were also somewhat more likely than whites to disagree that HCPs should collect race/ethnicity data so they can better train their staff to treat patients of different backgrounds (17.1% vs 4.4%, respectively; P=.007; Table 1). Attitudes did not vary by age, sex, and education.

Table 1.

Attitudes Regarding the Need to Collect Data on Race and Ethnicity and Use this to Improve Care*

| White (N=91) | Black/African American (N=70) | Hispanic (N=20) | Multiracial/Multiethnic (N=18) | Total†(N=220) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It is important for hospitals and clinics to collect information from patients about their race or ethnic background. Would you say that you: | |||||

| Strongly agree (%) | 47.3 | 34.3 | 35.0 | 52.9 | 42.5 |

| Somewhat agree (%) | 37.4 | 41.4 | 35.0 | 29.4 | 37.4 |

| Unsure (%) | 6.6 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 11.8 | 6.4 |

| Somewhat or strongly disagree (%) | 8.8 | 20.0‡ | 25.0‡ | 5.9 | 13.7 |

| It is important for hospitals and clinics to conduct studies to make sure all patients get the same high-quality care regardless of their race or ethnic background. Would you say that you: | |||||

| Strongly agree (%) | 92.3 | 92.9 | 95.0 | 100 | 93.2 |

| Somewhat agree (%) | 6.6 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 3.6 |

| Unsure (%) | 1.1 | 4.3 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 |

| Somewhat or strongly disagree (%) | 0 | 0 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.9 |

| It is important for hospitals and clinics to understand the race and ethnic background of their patients so they can train staff to treat patients from different backgrounds. Would you say that you: | |||||

| Strongly agree (%) | 72.5 | 60.0 | 65.0 | 77.8 | 66.4 |

| Somewhat agree (%) | 17.6 | 20.0 | 25.0 | 11.1 | 18.6 |

| Unsure (%) | 5.5 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 0 | 4.6 |

| Somewhat or strongly disagree (%) | 4.4 | 17.1§ | 5.0 | 11.1 | 10.4 |

Stratified results are not shown for Asians (N=10), American Indians (N=1), and other/refusals (N=5) because the number of participants in these categories was too small for meaningful comparisons.

One participant did not answer the first question (N=219).

P=.04 for pairwise comparison of whites and blacks and P=.04 for pairwise comparison of whites and Latinos.

P=.007 for pairwise comparison between whites and blacks.

Patients' Comfort Level Reporting Their Own Race and Ethnicity

Overall, 62.7% of patients reported that they would have a high comfort level giving a clerk information about their race and ethnicity (comfort level ≥8 on 10-point scale; Table 2). However, 21.8% were only moderately comfortable (comfort level 4 to 7), and 15.5% were uncomfortable (comfort level 1 to 3). Comfort levels were significantly lower for blacks compared with whites (P=.03). Among those who were not fully comfortable giving race and ethnicity information to a clerk (i.e., comfort level <10; N=112), people said they would feel more comfortable if they were asked this question by a nurse (42.0%) or a doctor (54.4%).

Table 2.

Comfort Providing Information on Race/Ethnicity*

| White (N=91) | Black/African American (N=70) | Hispanic (N=20) | Multiracial/Multiethnic (N=18) | Total†(N=220) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How comfortable would you be giving the clerk this information on a scale from 1 to 10, 1 is very comfortable and 10 very uncomfortable?‡ | |||||

| 1 to 3 (%) | 8.8 | 24.3 | 20.0 | 16.7 | 15.5 |

| 4 to 7 (%) | 23.1 | 27.1 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 21.8 |

| 8 to 10 (%) | 68.1 | 48.6 | 80.0 | 66.7 | 62.7 |

| How concerned would you be that this information could be used to discriminate against you or other patients?§ | |||||

| Not concerned at all (%) | 43.2 | 17.1 | 50.0 | 44.4 | 34.1 |

| A little concerned (%) | 15.9 | 8.6 | 30.0 | 16.7 | 14.8 |

| Somewhat concerned (%) | 21.6 | 21.4 | 10.0 | 16.7 | 19.8 |

| Very concerned (%) | 19.3 | 52.9 | 10.0 | 22.2 | 31.4 |

| If you knew that a hospital or clinic collected information on race and ethnicity, how would this affect your decision to go there again for your care?∥ | |||||

| Somewhat/much more likely (%) | 4.4 | 12.3 | 5.3 | 16.7 | 8.4 |

| About the same (%) | 88.9 | 69.2 | 68.4 | 72.2 | 77.5 |

| Somewhat/much less likely (%) | 6.7 | 18.5 | 26.3 | 11.1 | 14.1 |

Stratified results are not shown for Asians (N=10), American Indians (N=1), and other/refusals (N=5) because the number of participants in these categories was too small for meaningful comparisons.

Three whites did not answer the second question, so the subgroup total was 88 and the total number who responded was 217. One white, 1 Hispanic, and 5 blacks did not answer the third question, so the subgroup totals were 90, 19, and 65, respectively, and the total number who responded was 213.

P =.02 for pairwise comparison between whites and blacks.

P<.001 for pairwise comparison between whites and blacks.

P=.009 for pairwise comparison between whites and blacks and P=.03 for pairwise comparison between whites and Hispanics.

Patients' Concerns About Providing Information

Despite these relatively high levels of comfort about providing race and ethnicity information, over half of participants were somewhat concerned (19.8%) or very concerned (31.4%) that this information could be used to discriminate against patients (Table 2). Among blacks, 74.3% were somewhat or very concerned compared with 40.9% for whites (P<.001). Patients' concern that this information could be used to discriminate against people showed a strong inverse association with their self-reported comfort (Pearson correlation coefficient −0.41, P<.001). In a multivariate model, the lower level of comfort among blacks was almost completely explained by their higher level of concern about discrimination. The β coefficient for black race was −1.6 (95% confidence interval (CI) −2.5 to −0.6; P=.002) in the baseline model of comfort level that only included race and ethnicity as independent variables. When we added concern about discrimination as a covariate to this model, the β coefficient for black race decreased to −0.5 (95% CI −1.9 to 0.9) and was no longer significant (P=.49). Age, gender, years of school completed, race of the interviewer, and racial concordance between the patient and the interviewer were not significantly associated with patients' comfort level.

A total of 8.4% said they would be more likely to go to a hospital or clinic that routinely collected information about race and ethnicity, whereas 14.1% said they would be less likely to go. Compared with whites (6.7%), blacks and Hispanics more often said that they would be somewhat or much less likely to go to a hospital or clinic that routinely collected this information (18.5% and 26.3%, respectively; P=.009 and .03 for pairwise comparisons with whites, respectively; Table 2). Reporting a comfort level of 3 or less was strongly associated with being somewhat or much less likely to go to a hospital or clinic that routinely collected this information (adjusted odds ratio 5.2; 95% CI 1.6 to 17.1; P=.006). Hispanics were somewhat or much less likely to go to a hospital or clinic that routinely collected this information even after adjusting for comfort level (adjusted odds ratio 4.9; 95% CI 1.1 to 21.2; P=.03).

Changes in Comfort Levels After Hearing Introductory Reasons

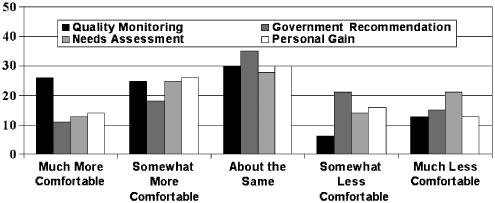

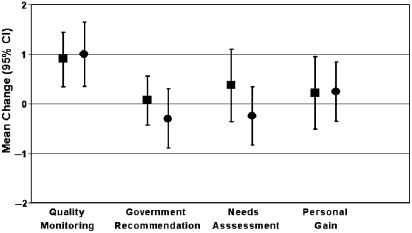

Of the 4 statements explaining the rationale for collecting information on race and ethnicity (Appendix), the Statement 1 (“Quality Monitoring”) had the most positive impact on patients' comfort level (Fig. 1). Of the 112 (50.9%) participants who were not completely comfortable reporting their race and ethnicity (i.e., comfort score <10), 25.0% said that Statement 1 made them somewhat more comfortable and 25.6% said the statement made them much more comfortable. The change in comfort level was significantly higher than for any of the other statements (Fig. 1; P<.001, P=.03, and P=.05 compared with Statements 2, 3, and 4, respectively). Similarly, when we asked people to rate their comfort level a second time after hearing each statement, the mean change in comfort level was higher for Statement 1 than for Statements 2, 3, and 4 (+1.0 vs −0.2, 0.0, and +0.2, respectively; P<.001, P=.001, and P=.004, respectively; Fig. 2). Among the 68 nonwhite participants who were not completely comfortable giving their race and ethnicity at baseline, the mean change in comfort level for Statements 2 and 3 was actually negative (Fig. 2). In direct comparisons, the proportions of people who preferred each of the 4 Statements were 37.8%, 5.0%, 25.0%, and 19.1%, respectively; 9.5% had no clear preference. The proportions were similar for whites, blacks, and Hispanics.

FIGURE 1.

Change in comfort level reporting race and ethnicity after hearing 4 explanations. The data shown are for the 112 patients who said they were not completely comfortable giving race/ethnicity information at baseline (i.e., comfort level <10). P<.001, P=.03, and P=.05 in pairwise comparisons of Statement 1 to Statements 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Mean change in comfort level (±95% confidence intervals) reporting race and ethnicity in response to the 4 statements for whites (▪) and nonwhites (•). Among patients who said they were not completely comfortable giving this information when first asked (i.e., baseline comfort level <10; N=112).

DISCUSSION

Patients reported a high level of support for hospitals and clinics routinely collecting information on race and ethnicity, even among African-American and Latino patients, and almost everyone agreed that hospitals and clinics should conduct studies to ensure all patients get similarly high-quality care. The level of support seen in this study is substantially higher than in a previous national survey, possibly because this earlier study focused on legislative mandates for data collection and assessed attitudes more generally for HCPs, health insurers, and employers.11 There was weaker support for collecting race/ethnicity data to understand patients' background and train staff “to treat patients from different backgrounds,” especially among African Americans. Some participants may have thought this statement implied that patients would be stereotyped and not treated as a unique individual, which is a concern raised about “cultural competence” training programs that teach stereotypical patient beliefs rather than communication skills.13

This endorsement of data collection is shrouded by a veil of concern. Much of patients' discomfort arises from fears that this information could be used to discriminate against patients. Almost three-fourths of African Americans were somewhat or very concerned about this (Table 2), as were over 40% of whites. Blacks lower comfort level providing race/ethnicity information was almost completely explained by their higher level of concern about discrimination. Providing assurances to patients that data will be kept confidential and that a limited number of people will have access to this data may help reduce levels of concern. Although we examined the effect of 4 statements designed to increase comfort, none of these specifically addressed confidentiality and limitations on who would have access to race and ethnicity data.

It is troubling that 18.5% of African Americans and 26.3% of Hispanics said they would be less likely to go to a hospital or clinic that collected information about race and ethnicity. In general African Americans trust their physicians and the health care system less than whites.14–16 This distrust is because of many factors, including the legacy of research conducted by the United States Public Health Service that allowed blacks with syphilis to go untreated for decades even after penicillin became widely available (i.e., the “Tuskegee Syphilis Study”).17,18 For Hispanics, there may also be concerns that this information could be given to officials from the Immigration and Naturalization Service to identify undocumented immigrants.19 Individuals of Middle-Eastern ancestry may have similar concerns. Health care providers that want to collect race/ethnicity information should do so in partnership with community leaders so their concerns can be articulated and safeguards against abuse can be explored and implemented.

Our findings suggest that HCPs can address patients' concerns by explaining that this information will be used to monitor quality of care. Interestingly, patients responded less positively to the statement suggesting that their own care would be improved (Statement 4—“Personal Gain”). The latter statement may have seemed artificial or a false promise. We were surprised that the “Needs Assessment” statement (Statement 3) was not viewed more positively. In fact, this statement actually decreased nonwhite patients comfort level (Fig. 2). Patients may reject the concept of hiring staff based on their race and ethnicity as opposed to their skills. Alternatively, they may have been concerned that the staff “training” to which we referred would merely be teaching stereotypes.

The statement about government agencies recommending data collection (Statement 2) did not diminish patients' concerns. Some states recommend that hospitals collect race and ethnicity information (e.g., Texas),20 and the statement used in our study was similar to ones currently in use by some hospitals to explain why this information is being collected. Our results suggest that HCPs should not use statements like this in an attempt to pass responsibility to accrediting organizations or government agencies. Doing so carries the message that HCPs do not think this information is useful to them for improving quality of care or services they deliver.

This study has important limitations. The project was done at a single clinic, and the population was not a random sample. Most patients are middle and upper income, there are small numbers of patients of Asian and Middle-Eastern descent, and almost all are native English speakers. Attitudes may be different among individuals of lower socioeconomic status and those with limited English proficiency, especially those who perceive they have been victims of racism or discrimination. Individuals who were opposed to collecting race/ethnicity information may have been more likely to refuse to participate. In addition, patients who have an established relationship with a primary care physician may trust HCPs more than the average person, and they may therefore be more comfortable providing information on their race and ethnicity. Additional studies are needed to examine attitudes toward HCPs collecting race/ethnicity and language data using a large, diverse sample of the general population.

Collecting information on patients' race and ethnicity is a necessary first step toward eliminating disparities. Health care providers need to use this information to determine where quality of care differs to design focused interventions. Our results show this road will not be free of obstacles. Although patients' support this policy agenda, their concerns are significant and their attitudes could discourage some HCPs from collecting race and ethnicity information. This can be addressed by explaining to patients and community leaders the rationale for collecting these data and seeking their input about how best to do this. Most importantly, HCPs who collect this information must be true to their word: these data must be linked to measures of quality of care to examine disparities, initiatives to eliminate any disparities must be funded and executed, and the results must be openly shared with patients and communities.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by The Commonwealth Fund (grant number 20020739) and the Health Research and Educational Trust.

Appendix

Statements tested to determine if they were able to increase patients' comfort reporting their race/ethnicity

| Statement 1 (“Quality Monitoring”) |

| We want to make sure that all our patients get the best care possible, regardless of their race or ethnic background. We would like you to tell us your race or ethnic background so that we can review the treatment that all patients receive and make sure that everyone gets the highest quality of care |

| Statement 2 (“Government Recommendation”) |

| Several government agencies recommend that we collect information on the race and ethnic backgrounds of our patients as part of a national effort to make sure all patients have access to quality health care. Please tell me your race or ethnic background |

| Statement 3 (“Needs Assessment”) |

| We take care of patients from many different backgrounds. We would like you to tell us your race or ethnic background so that we can understand our patients better. This will help us decide who to hire, how to train our staff better, and what health information is most helpful for our patients |

| Statement 4 (“Personal Gain”) |

| We would like you to tell us your race or ethnic background so that we can ensure that all of our patients are treated equally. This will help us make sure you get the best care possible |

References

- 1.Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panel on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Medical Care. The Right to Equal Treatment. Washington, DC: Physicians for Human Rights; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, et al. Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA. 2000;283:2579–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bierman AS, Lurie N, Collins KS, et al. Addressing racial and ethnic barriers to effective health care: the need for better data. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:91–102. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panel on DHHS Collection of Race and Ethnicity Data. Eliminating Health Disparities: Measurement and Data Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of health services: bias, preferences, or poor communication? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:146–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasnain-Wynia R, Pierce D, Pittman MA. Who, What, When, Where: The Current State of Data of Collection on Race and Ethnicity in Hospitals. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkinson JO, MacDorman MF, Parker JD. Trends in births to parents of two different races in the United States: 1971–1995. Ethnic Disparities. 2001;11:273–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bureau US Census. US census quick facts. 2003. Available at http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html Accessed March 31, 2005.

- 10.League of Women Voters. Classification by race, ethnicity, color, or national origin. League of women voters 2003. Available at http://ca.lwv.org/lwvc/edfund/elections/2003/pc/prop54.html Accessed March 31, 2005.

- 11.Public Opinion Strategies. Key findings from a national survey conducted among adults who have health insurance coverage on behalf of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation on the issue of disparities in health care. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2005. Available at http://www.rwjf.org/news/POSfullMemo.pdf Accessed March 31, 2005.

- 12.Office of Management and Budget. Revisions of the standards for classification of federal data on race and ethnicity. Fed Regist. 1997;62:587–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betancourt JR. Cultural competence—marginal or mainstream movement? N Engl J Med. 2004;351:953–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, et al. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:358–65. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doescher MP, Saver BG, Franks P, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in perceptions of physician style and trust. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1156–63. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keating NL, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. Patient characteristics and experiences associated with trust in specialist physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1015–20. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones JH. Bad Blood, The Tuskeegee Syphilis Study. Revised Edition. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison RW. Impact of biomedical research on African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2001;93(suppl):6–7S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Immigrant Healthcare Attacked. Las Culturas.com. 2004. 10-15-0004. Available at http://www.lasculturas.com/aa/press_nclr_091404.htm Last accessed March 31, 2005.

- 20.Texas Health & Safety Code. 108.009(k), 2004.