Abstract

Background

Little information is available on physician characteristics and patient presentations that may influence compliance with evidence-based guidelines for acute low back pain.

Objective

To assess whether physicians' management decisions are consistent with the Agency for Health Research Quality's guideline and whether responses varied with the presentation of sciatica or by physician characteristics.

Design

Cross-sectional study using a mailed survey.

Participants

Participants were randomly selected from internal medicine, family practice, general practice, emergency medicine, and occupational medicine specialties.

Measurements

A questionnaire asked for recommendations for 2 case scenarios, representing patients without and with sciatica, respectively.

Results

Seven hundred and twenty surveys were completed (response rate=25%). In cases 1 (without sciatica) and 2 (with sciatica), 26.9% and 4.3% of physicians fully complied with the guideline, respectively. For each year in practice, the odds of guideline noncompliance increased 1.03 times (95% confidence interval [CI]=1.01 to 1.05) for case 1. With occupational medicine as the referent specialty, general practice had the greatest odds of noncompliance (3.60, 95% CI=1.75 to 7.40) in case 1, followed by internal medicine and emergency medicine. Results for case 2 reflected the influence of sciatica with internal medicine having substantially higher odds (vs case 1) and the greatest odds of noncompliance of any specialty (6.93, 95% CI=1.47 to 32.78), followed by family practice and emergency medicine.

Conclusions

A majority of primary care physicians continue to be noncompliant with evidence-based back pain guidelines. Sciatica dramatically influenced clinical decision-making, increasing the extent of noncompliance, particularly for internal medicine and family practice. Physicians' misunderstanding of sciatica's natural history and belief that more intensive initial management is indicated may be factors underlying the observed influence of sciatica.

Keywords: back pain, guidelines, practice variation, clinical vignette, decision making

Low back pain affects up to 80% of the working population during their lifetime and is the second most common reason for physician visits 1 and for work disability.2 Back pain accounts for an estimated $25 billion in annual medical costs in the United States.3

Factors related to the extensive burden of back pain may include variations in physicians' clinical management as the etiology of back pain is unclear.1,4 Clinical practice guidelines have been systematically developed to improve health care quality and reduce ineffective treatments. A number of evidence-based guidelines for the clinical management of acute back pain in primary care have been published since the first in 1987,5 including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, previously named the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research) guideline in 1994.6 More recent guidelines are based on newer evidence but have similar diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations to the AHRQ guideline.7

All guidelines recommend an initial evaluation to identify the approximately 5% of patients who present with “red flags.” Red flags are those findings that suggest significant pathology (i.e., vertebral fracture, tumor, infection, cauda equina syndrome, or serious nonspinal conditions) that require diagnostic studies and/or specialty referral as part of initial management.6

After ruling out such serious conditions, cases are categorized as nonspecific back pain or sciatica (approximately 85% and 5% of cases, respectively). Disabling symptoms are expected to resolve in up to 90% of patients within the first month, including over 50% of those with sciatica.8 The guideline intent is to change the care focus for both categories of back pain from pain relief to improved activity tolerance, and to limit unnecessary diagnostic and clinical treatment interventions during this period.6

Despite the proliferation of evidence-based back pain guidelines, prior studies, based on chart reviews or physician surveys, found a lack of consensus and compliance with them.9–13 However, these studies were based either on a small sample size, a single specialty group, or were completed more than a decade ago. This study's purpose was to assess the extent to which the clinical decision-making in a more recent, national sample of primary care physicians was consistent with the guideline, and whether responses varied with the presentation of sciatica or by physician characteristics.6

METHODS

Questionnaire Development

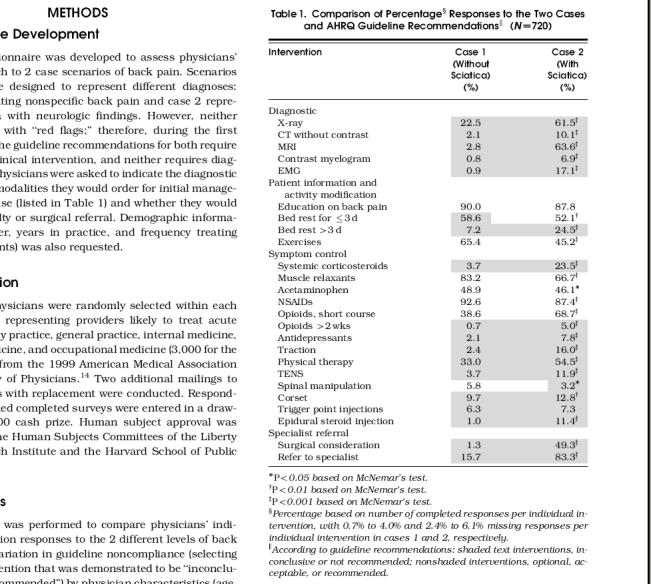

A 2-page questionnaire was developed to assess physicians' clinical approach to 2 case scenarios of back pain. Scenarios (Appendix) were designed to represent different diagnoses: case 1 representing nonspecific back pain and case 2 representing sciatica with neurologic findings. However, neither case presented with “red flags;” therefore, during the first month of care, the guideline recommendations for both require only minimal clinical intervention, and neither requires diagnostic testing. Physicians were asked to indicate the diagnostic and treatment modalities they would order for initial management of each case (listed in Table 1) and whether they would consider specialty or surgical referral. Demographic information (age, gender, years in practice, and frequency treating back pain patients) was also requested.

Table 1.

Comparison of Percentage§ Responses to the Two Cases and AHRQ Guideline Recommendations∥(N=720)

Data Collection

Six hundred physicians were randomly selected within each specialty group representing providers likely to treat acute back pain: family practice, general practice, internal medicine, emergency medicine, and occupational medicine (3,000 for the initial mailing) from the 1999 American Medical Association (AMA) Directory of Physicians.14 Two additional mailings to nonrespondents with replacement were conducted. Respondents who returned completed surveys were entered in a drawing for one $500 cash prize. Human subject approval was received from the Human Subjects Committees of the Liberty Mutual Research Institute and the Harvard School of Public Health.

Data Analysis

McNemar's test was performed to compare physicians' individual intervention responses to the 2 different levels of back pain severity. Variation in guideline noncompliance (selecting at least 1 intervention that was demonstrated to be “inconclusive” or “not recommended”) by physician characteristics (age, gender, specialty, years in practice) was assessed using multiple logistic regression.15

RESULTS

Of the 3,238 physicians solicited over 3 mailings, 397 surveys were excluded because of wrong addresses or because respondents were not practicing in primary care, did not treat back pain, or failed to complete demographic or case questions. Of the remaining 2,851 questionnaires, 720 were completed (25% response rate). Response rate by specialty ranged from 18% for general practice to 34% for family practice.

Males comprised 81% of the respondents. Mean and median respondent ages were 49.3 and 48.0 (range, 27 to 85 years). The mean and median practice durations were 20.3 and 19.0 years (range, 1 to 58 years). Of the overall sample, family practice was the best represented (27%) and general practice the least represented (14%). Respondents practiced in 48 states and the District of Columbia, with an equal distribution across the 4 U.S. Census regions.

Table 1 presents the percentage of responses by intervention, the McNemar's test results, and guideline recommendations.6 Sciatica was significantly associated with increased noncompliance for the majority of interventions.

In cases 1 (without sciatica) and 2 (with sciatica), 26.9% and 4.3% of the physicians fully complied with the guideline, respectively. Years in practice was included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis as it better reflects clinical experience than age.

In case 1, differences in years in practice and specialty group were significant (Table 2) For each year in practice, the odds of guideline noncompliance increased 1.03 times (95% confidence interval [CI]=1.01 to 1.05) for case 1 with similar odds for case 2.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios from Multivariate Logistic Regression Models for Noncompliance with the AHRQ Guideline for Cases 1 and 2

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1 (without sciatica) | ||

| Gender | 0.98 | 0.63 to 1.53 |

| Years in practice ‡ | 1.03 | 1.01 to 1.05† |

| Occupational medicine (n=155) | 1.00 | |

| General practice (n=103) | 3.60 | 1.75 to 7.40† |

| Family practice (n=196) | 1.37 | 0.85 to 2.21 |

| Emergency medicine (n=146) | 2.22 | 1.30 to 3.78† |

| Internal medicine (n=120) | 2.95 | 1.63 to 5.36† |

| Case 2 (with sciatica) | ||

| Gender | 0.88 | 0.35 to 2.21 |

| Years in practice ‡ | 1.04 | 1.00 to 1.08* |

| Occupational medicine | 1.00 | |

| General practice | 2.10 | 0.57 to 7.81 |

| Family practice | 3.28 | 1.18 to 9.11* |

| Emergency medicine | 2.97 | 1.03 to 8.57* |

| Internal medicine | 6.93 | 1.47 to 32.78* |

P<.05

P<.001.

Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for 1-year increase

c statistic (case 1)=0.65

c statistic (case 2)=0.69.

Occupational medicine was selected as the referent specialty based on the best compliance (36.1% and 12.3% full compliance for cases 1 and 2, respectively). General practice had the greatest odds of noncompliance (3.60, 95% CI=1.7 to 7.40) in case 1, followed by internal medicine and emergency medicine. Results for case 2 reflect the influence of sciatica. Internal medicine had substantially higher odds (vs case 1) and the greatest odds of noncompliance of any specialty (6.93, 95% CI=1.47 to 32.78), followed by family practice and emergency medicine. Gender was not associated with noncompliance in either case.

DISCUSSION

Surveyed physicians departed from the AHRQ guideline to some extent for the case with nonspecific back pain. However, those in general practice and internal medicine and, to a lesser extent, those in emergency medicine, were significantly more likely to choose at least 1 nonevidence-based intervention for patients without sciatica.

In case 2, sciatica dramatically influenced clinical decision-making with almost all physicians selecting at least 1 nonevidence-based intervention. Increases in noncompliance within internal medicine and family practice were particularly substantial. Between-specialty differences were also pronounced, even when controlling for years in practice and gender. While a diagnosis of sciatica might suggest more intensive clinical intervention, the guidelines for the first month still recommend conservative interventions to allow time for symptom resolution (which occurs in over 50% of patients with sciatica) and for the patient to overcome activity limitations.6 More intensive management approaches may inhibit activity restoration and have been shown to prolong disability.9

The significance of years in practice in noncompliance is consistent with the results of a recent systematic review of empirical studies. More-experienced physicians were found to demonstrate less knowledge, be less likely to follow standards of practice, and have less successful outcomes.16

The present study sampled a national population of primary care providers and was not limited to 1 specialty group or health plan. The response rate was similar to a previous survey of nonsurgical physicians regarding back pain treatment (25% to 33%),11 and was within the reported range of 11% to 100% for physician surveys.17 Gender and age closely matched the 1998 AMA membership (21% female, median age=45 years),18 and respondents were similarly distributed across major U.S. Census regions. These sample characteristics suggest that a response bias is less likely. However, a potential limitation was the use of a lottery versus per-individual incentives that could create a response bias toward those who respond for altruistic reasons.

The present study used comparative scenarios with variation in diagnosis. Scenarios have been challenged in their ability to predict an individual physician's clinical behavior lacking the physician-patient interaction related to pain behavior, patient perceptions of satisfactory care and outcome, or other factors not included in a scenario.19,20 However, Carey and Garrett 20 concluded that vignette responses can be representative of the behavior of a population of physicians. Another potential limitation was an order of presentation effect. By presenting the sciatica case second, physicians may have assumed their management should differ.

CONCLUSIONS

More than a decade after promulgation of evidence-based guidelines for low back pain, a majority of primary care physicians continued to be noncompliant. Sciatica dramatically influenced clinical decision-making, increasing the extent of noncompliance, particularly for internal medicine and family practice. More-experienced physicians were less compliant than their colleagues, irrespective of diagnosis.

Reasons suggested for not following practice guidelines include lack of awareness, familiarity, self-efficacy, or outcome expectancy, and inertia of previous practice or external barriers.21 In the current study, incomplete understanding of sciatica's natural history, belief that early diagnostic studies and referrals are indicated by radiculopathy, disagreement with evidence-based recommendations, concern for litigation, or uncertainty regarding self-efficacy for management of a potential surgical case could underlie the observed influence of sciatica. Future research is needed to determine the factors influencing noncompliance before selecting effective interventions to change physicians' practice behavior.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Mohammed Mahmud for his contributions to the conceptualization of the study, Santosh Verma for statistical consultation, Marcia Chertok for her technical assistance, and Glenn Pransky, William Shaw, and Raymond McGorry for their reviews of earlier drafts of the manuscript. Funding support: Partial support received from CDC (NIOSH) Training Grant T42/CCT 122961.

Appendix

Case Scenarios

Case 1. A 28-year-old married auto mechanic with no prior history of back problems reports that he experienced sudden onset of back pain while bending forward and to the side as he was picking up a tire yesterday morning. Bed rest slightly improved his pain and he returned to work today. However his back pain progressively increased throughout the day, and by the end of the day he was unable to bend and had to leave work. He denies any radiation of back pain down either leg. His past medical history is unremarkable. Physical examination reveals markedly limited forward and right lateral flexion, as well as right paraspinal muscle spasm and tenderness but no loss of lumbar lordosis. Both straight leg raise (SLR) and Patrick's tests are negative. Motor, sensory and reflex tests are normal.

Case 2. A 35-year-old machinist has had occasional low back discomfort over the last 2 years but has not sought any medical advice. One week ago he felt excruciating pain with radiation down his left leg after pushing a heavy object at work that caused him to miss 3 days from work. After returning to work he experienced sharp pain in his lower back area with tingling and numbness in his left thigh, posterior calf, and lateral aspect of his left foot, mostly after prolonged standing and bending forward. He denies any bowel or bladder dysfunction. Past medical history is negative for cancer, immunosuppression or other systemic diseases. Your clinical evaluation reveals decreased pinprick sensation over the posterior aspect of the left calf and lateral foot, a diminished ankle jerk, but no motor weakness. Both SLR on the left and cross-over SLR tests are positive and limited to 45°. Patrick's test is negative.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hart GL, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC. Physician office visits for low back pain: frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns from a national survey. Spine. 1995;20:11–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Conrad D, Volinn E. Cost, controversy, crisis low back pain and health of the public. Annu Rev Pub Health. 1991;12:141–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.12.050191.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frymoyer JW. An overview of the incidences and costs of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991;22:263–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Wheeler K, Ciol MA. Physician variation in diagnostic testing for low back pain who you see is what you get. Arth Rheum. 1994;37:15–22. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spitzer WO, LeBlanc FE, Dupuis M. Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders. Spine. 1987;12:S1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigos S, Bowyer O, Braen G, et al. Acute low back problems in adults: clinical practice guideline No. 14. AHCPR publication No. 95-0642. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. December. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Burton KA, Waddell G. Clinical guidelines for the management of LBP in primary care an international comparison. Spine. 2001;26:2504–14. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson GB, Svensson HO, Oden A. The intensity of work recovery in low back pain. Spine. 1983;8:880–4. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198311000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahmud MA, Webster BS, Courtney TK, Matz S, Tacci JA, Christiani DC. Clinical management and the duration of disability for work-related low back pain. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42:1178–87. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200012000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schers H, Braspenning J, Drijver R, Wensing M, Grol R. Low back pain in general practice reported management and reasons for not adhering to the guidelines in The Netherlands. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:640–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Wheeler K, Ciol MA. Physician views about treating low back pain results of a national survey. Spine. 1995;20:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bishop PB, Wing PC. Compliance with clinical practice guidelines in family physicians managing worker's compensation board patients with acute lower back pain. Spine J. 2003;3:442–50. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(03)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiIorio D, Henley E, Doughty A. A survey of physician practice patterns and adherence to acute low back guidelines. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1015–21. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Directory of Physicians in the United States on CD-ROM, 1998. Chicago: American Medical Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.SPSS Inc. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 2002. SPSS 11.0. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. The relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:260–73. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–36. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AMA Council on Long Range Planning and Development. Demographic Characteristics of AMA Leadership. CLRPD Report 2– I–98. Chicago: American Medical Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones TV, Gerrity MS, Earp J. Written case simulations do they predict physicians' behavior? J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:805–15. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90241-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carey TS, Garrett J. Patterns of ordering diagnostic tests for patients with acute low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:807–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-10-199611150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]