Abstract

BACKGROUND

Poor mood adjustment to chronic medical illness is often accompanied by decrements in function.

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the effectiveness of a telephone-based intervention for psychologic distress and functional impairment in cardiac illness.

DESIGN

Randomized, controlled trial.

METHODS

We recruited survivors of acute coronary syndromes using the Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) with scores indicative of mood disturbances at 1-month postdischarge. Recruited patients were randomized to experimental or control status. Intervention patients received 6 30-minute telephone counseling sessions to identify and address illness-related fears and concerns. Control patients received usual care. Patients' responses to the HADS and the Workplace Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) were collected at baseline, 2, 3, and 6 months using interactive voice recognition technology. At baseline, the PRIME-MD was used to establish diagnosis of depression. We used mixed effects regression to study changes in outcomes.

RESULTS

We enrolled 100 patients. Mean age was 60; 67% of the patients were male. Findings confirmed that the intervention group had a 27% improvement in depression symptoms (P=.05), 27% in anxiety (P=.02), and a 38% improvement in home limitations (P=.04) compared with controls. Symptom improvement tracked those for WSAS measures of home function (P=.04) but not workplace function.

CONCLUSIONS

The intervention had a moderate effect on patient's emotional and functional outcomes that were observed during a critical period in patients' lives. Patient convenience, ease of delivery, and the effectiveness of the intervention suggest that the counseling can help patients adjust to chronic illness.

Keywords: chronic medical illness, depression, anxiety, psychological adjustment, function

Diagnosis and progression of chronic medical illness represent critical periods in patients' lives when psychologic well-being is often adversely affected. Poor adjustment to chronic illness can lead to depression and anxiety as well as functional declines. Although patients may subsequently adjust to new or progressing illness, others continue to exhibit symptoms of depression, anxiety, and impairment.

Difficulty in adjustment to chronic illness appears common among patients with coronary heart disease.1 Depression appears to be a robust and prognostic cardiac risk factor associated with increased morbidity and mortality and complicates management of cardiac illness.2–10 Studies have documented that depression treatment in cardiac patients reduces symptoms and may decrease morbidity and disability, and improve quality of life.11,12 Furthermore, reviews of depression and heart disease suggest a gradient relationship between depression and risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes.13

The Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD), which focused on nonpharmacologic treatment of depression in cardiac patients, examined whether recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) and mortality were reduced by cognitive behavioral therapy treatment and antidepressants, as necessary, among MI survivors recruited in hospital. At 6 months, experimental patients experienced improvement in depressive symptoms (∼25%), although by month 30 this effect did not persist. At 4 years of follow-up, no decrease in mortality was observed.14,15 Several design factors in ENRICHD could have contributed to these negative mortality findings, including antidepressant effects on platelets, in-hospital recruitment of patients whose depression may have resolved in the posthospitalization period,16 and contamination because of intervention by nurses monitoring control patients.

This article describes a randomized, controlled trial of a telephone-based treatment for emotionally distressed medically ill patients with roots in practice guidelines for psychiatric consultation in general medical settings and medical crisis counseling programs.17–20 The intervention is not psychodynamic or interpersonal psychotherapy, but is a cognitive treatment that helps patients identify and manage the challenges of living with a chronic condition. It is goal oriented, time limited, and issue focused and extends other telephone interventions for depression by modulating risk of depression, anxiety, and functional decrements through improved adjustment to illness.21–24 We used interactive voice recognition (IVR) for data collection, thus minimizing the likelihood of contamination of control patients. In this study, we hypothesized that recently hospitalized patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who received counseling for chronic medical illness would be less likely to have depression, anxiety, and functional disability in the home and workplace than those receiving usual care.

DESIGN AND METHODS

Participants

The study was a prospective, 2-arm, randomized, controlled trial of a telephone-based intervention versus usual care in the treatment of ACS survivors.

Patients were identified by medical chart review in the coronary care unit by research nurses to determine the presence of study criteria. Exclusion criteria included mental health care in the prior 3 months, psychoactive drug use during the past year, and diagnosis of substance abuse during the past year. In addition to ACS, patients needed to be age 35 or older, able to speak English, have access to a touch-tone phone, and have symptoms of depressive illness or anxiety as indicated by a score of 7 or more on either of the subscales of the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS, see Appendix I, online). The institutional review boards of participating organizations approved the study protocol.

Recruitment and Informed Consent

Patient recruitment (September 2001 to August 2003) began during the index hospitalization at 2 Boston teaching hospitals. After chart review, the research nurse contacted the patient's attending physician for permission to approach the patient (Fig. 1) with study information. If the subject expressed interest and chose to participate, the informed consent form was signed at that time. Otherwise, the consent forms and an addressed, postage-paid envelope were provided. With patients' permission, the study coordinator contacted interested patients by telephone postdischarge. If they agreed to participate, they signed and returned the consent form. Informed consent could be obtained for up to 30 days following hospital discharge. Once patients consented, the study coordinator administered the 14-item HADS by phone to assess symptoms of anxiety and depression.25 Subjects with scores between 7 and 15 on either the anxiety or depression scale were enrolled and randomized by coin flip. Because of chance, the experimental group contained 6 more patients than the control group. Patients with symptoms of severe depression (HADS>15) were referred for emergent care.

FIGURE 1.

Study design flow chart.

Intervention Group

Within a week following randomization, experimental patients began the 8-week treatment according to protocol that was described in detail in a treatment manual. Sessions were 30 minutes and conducted by doctoral-level clinicians (a psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, and internist). Patients were expected to complete 6 sessions but allowed to participate in as few as 3 if the therapist and patient agreed that all 8 issues set forth during treatment were reviewed, and that treatment goals were reached. In the first contact, the clinicians introduced themselves, reviewed the protocol, answered questions, and asked about the experience of the patient's recent illness on emotional well-being and work function. The first contact reviewed 8 fears commonly experienced by those living with chronic medical conditions: loss of control, loss of self-image, dependency, stigma, abandonment, anger, isolation, and fear of death.26 With the counselor, patients identified barriers to adjustment to medical illness and rank ordered these. In sessions 2 to 6, patients and counselors identified strategies to address these barriers. The counselor reviewed progress toward goals with reinforcement and encouragement. A session log tracked the issues reviewed in each session. At weekly meetings the counselors reviewed cases and notes with the research team to monitor fidelity to the intervention. Appendix II (available online) presents an overall schemata of the intervention.

Control Group

Control patients received a booklet on coping with cardiac illness typical of those given at hospital discharge and were instructed to contact their primary care physician if they experienced any warning signs of depression. They were advised to continue follow-up with their primary care and specialist physicians.

Measurement Protocol and Suicidal Protocol

Information prepared by the study coordinator included a unique study identifier, screening results, expected call type (screen, baseline or 2, 3, or 6 months), and expected and actual call dates. A behavioral data management organization collected baseline and follow-up data at months 2, 3, and 6 using IVR, an automated telephone system that speaks to a patient and automatically enters responses into a database. Patient failure to call into the IVR system to report data triggered a fax to the study coordinator after allowing for a 3-day window for the patient to complete the call. At baseline, IVR measures included measures of mood, function at home and work, self-rated impression of health, and anger. At baseline and follow-up, suicidal ideation/intent was assessed using the HADS and supplemental questions; responses suggestive of risk of self-harm generated an immediate page to the study psychiatrist, according to IRB-approved protocol.

Demographic and Illness Variables

Patient data retrieved from hospital records included age, gender, race, hospital admission and discharge dates, length of stay, cardiac discharge diagnosis, and cardiac procedures. Experimental status assigned by randomization by the study coordinator was entered into the study registry.

Indicator of Psychologic Distress: Depression and Anxiety Symptoms

Depression and anxiety symptoms were assessed with the HADS that contains 7 depression and 7 anxiety items rated on 4-point Likert scales (Appendix I). Each scale is scored from 0 to 21, with 0 to 3 considered in the normal range, 4 to 7 subclinical depression, and 8 to 21 “depressed.” Patients with a score of 7 or higher on the depression or anxiety subscale at the postdischarge screening were eligible to participate. The cutoff on the depression and anxiety scales was lenient to maximize inclusion of distressed patients, including the upper end of subthreshold depression or anxiety. We used the HADS to measure mood changes during follow-up as it emphasized cognitive rather than somatic symptoms.

Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)

Study measures to examine changes in function were based on the work and home impairment subscales of the WSAS,27 a validated measure of self-reported functional impairment in work, home management, social and private leisure, and personal relationships. Each of the 5 domains is scored from no impairment (0) to severe impairment (8), with a score of 3 to 5 suggestive of moderate impairment.

State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI)

The 10-item State Anger subscale of the STAXI was used to assess intensity of feelings of anger currently experienced by the patient. This is a 10-item stand-alone scale that measures the individual's current feelings of anger. Items are rated on a 4-point scale and assigned a score between 1 and 4.

Prime-MD

At baseline, we used the 15-item mood module of the PRIME-MD designed to diagnosis DSM-IV depression.28

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses consisted of descriptive and intent-to-treat modeling procedures. Descriptive statistics for baseline characteristics included t-tests and χ2statistics to validate randomization. Tests and estimates of intent to treat differences for study outcomes were based on growth curve models in which patient-level baseline and change over time were considered random effects and treatment status, time, and the interaction of these variables were fixed effects. Time at the end of follow-up (month 6) was coded as 0 in order to contrast the difference between levels of study outcomes between experimental and control groups. We compared unconditional means, unconditional growth models (fixed time), and conditional models (fixed time, experimental status, and time × interaction) to examine the variance parameters of the models and estimate changes in variance with the addition of variables to the models. An unstructured covariance structure was used. Goodness of fit was assessed with Akaike's information criterion. We assumed a linear trend model that provided a better fit than curvilinear models. We used the multiple imputation methods of Rubin to examine if data were missing randomly and did not observe any nonrandom missingness. Based upon other studies that reported mean improvement in HADS depression scores of 1.5 to 2.0 (effect size of∼0.2), we estimated that a total sample of 68 patients was necessary to detect a difference of 1.75 units in mean HADS depression or anxiety scores (80% power, 2-sided, α=0.05) that represented a 20% to 30% decrease in mood symptoms, comparable with that observed in ENRICHD. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.

RESULTS

Enrollment, Baseline, and Follow-Up Statistics

Between September 2001 and August 2003, we identified 706 potential participants (Fig. 1). Of these, 188 (36.6%) were eliminated because of the presence of exclusion criteria. Another 238 (33.7%) declined participation. Of 280 patients administered the HADS, 100 (35.7%) met the inclusion criterion of 7 to 15 on either or both measures. Of these 100, 47 (47%) were randomized to control and 53 (53%) to experimental status. Thirteen patients (27.7%) were lost from the postrandomization control group, which included 1 death. Eight experimental patients (15.1%) dropped out of the study before baseline measures were collected. The final cohort consisted of 79 patients (34 control patients and 45 experimental patients). Dropouts were comparable with remaining patients for baseline characteristics as determined by standard t- and χ2statistics (Table 1) Of the 79 study patients, 37 (47%) met both anxiety and depression inclusion criteria; of the remaining 42 patients, 31 met the depression but not anxiety criterion and 11 only the anxiety criterion.

Table 1.

Key Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants by Treatment Status

| Variable | Control Patients (N=34) | Experimental Patients (N=45) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.7 (9.8) | 59.9 (10.2) |

| HADS score | ||

| Depression subscale | 6.5 (3.8) | 8.5 (3.6) |

| Anxiety subscale | 7.1 (2.9) | 8.1 (3.7) |

| Length of stay | 3.1 (4.1) | 3.6 (3.3) |

| State anger scores | ||

| Anger scores in both gender groups | 15.8 (3.2) | 18.0 (5.2) |

| Anger scores among females | 14.3 (2.7) | 17.5 (4.5)* |

| Anger scores among males | 16.5 (3.2) | 18.3 (5.5) |

| Workplace social adjustment scores | ||

| Work † | 3.8 (2.2) | 3.6 (2.1) |

| Home management | 3.0 (2.1) | 3.1 (2.1) |

| DSM-IV depressive disorders ‡ | ||

| Major depressive disorder | 29.4% (10) | 37.8% (17) |

| Major depressive disorder, partial remission | 11.8% (4) | 11.1% (5) |

| Dysthymia | 17.6% (6) | 15.6% (7) |

| Double depression | 5.9% (2) | 11.1% (5) |

| Acute coronary syndrome § | ||

| Angina with procedure | 5.9% (2) | 6.7% (3) |

| Angina without procedure | 2.9% (1) | 2.2% (1) |

| MI with procedure | 23.5% (8) | 40.0% (18)* |

| MI without procedure | 5.9% (2) | 2.2% (1) |

| Other ischemic heart disease with procedure ¶ | 58.8% (20) | 40.0% (18)* |

| Other ischemic heart disease without procedure ¶ | 2.9% (1) | 8.9% (4) |

| Race | ||

| Black | 5.9% (3) | 6.7% (3) |

| White | 88.2% (40) | 88.9% (40) |

| Missing | 5.9% (2) | 4.4% (2) |

| Female gender | 35.3% (12) | 31.1% (14) |

Significantly different between control and experimental groups at P <.05 level

Excluded 7 patients who were retired or unemployed

DSM-IV major depressive disorder determined from the PRIME-MD

Acute coronary syndromes is defined as coronary artery disease resulting in acute myocardial ischemia, and includes unstable angina, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Other ischemic heart disease encompasses cardiac symptoms secondary to coronary heart disease, including unstable angina, arrhythmia secondary to ischemia, and heart block.

HADS, Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale; MI, myocardial infarction.

Table 1 indicates that at randomization groups were balanced with a predominance of older patients and males reflecting the epidemiology of coronary heart disease. We observed a higher procedure rate for experimental patients with a principal diagnosis of MI than control patients (40.0% vs 23.5%) while for the category of “other ischemic heart disease” we observed the reverse pattern with a rate of 58.8% in control patients versus 40.0% among experimental patients but these differences were not significant (χ2=3.0, P=.10).

Thirty-six percent of the study cohort (n=27) met PRIME-MD criteria for DSM-IV major depressive disorder with a mean HADS score of 10.2 (SD=3.6) at baseline. State anger scores for males tended to be higher at baseline than those for females but this difference did not reach significance (difference=2.2, P=.14). Female subjects had significantly lower state anger scores than controls (difference=3.2, P=.04). The mean number of telephone sessions completed was 4.2 of 6.

Treatment Effects on Depression and Anxiety Symptoms

Figure 2 illustrates the observed mean depression score and standard deviations at each study time point. Regression results showed a significant decrease in depression scores from baseline that was greater in the intervention group than controls (β=−0.39, P=.03,Table 2 as well as a final depression score that is 1.96 units lower in the experimental group at month 6 (P=.04).

FIGURE 2.

Treatment effects on depression.

Table 2.

Treatment Effects on Study Outcomes over Time

| Estimate | Standard Error | t-Value | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental effects on depressive symptoms 26% reduction | ||||

| Intercept | 7.5 | 0.70 | 11.1 | <.0001 |

| Time | −0.07 | 0.12 | −0.54 | .599 |

| Experimental status * | −1.96 | 0.96 | −2.02 | .046 |

| Experimental status × time | −0.39 | .16 | −2.44 | .016 |

| Experimental effects on anxiety symptoms 25% reduction | ||||

| Intercept | 8.8 | 0.61 | 14.6 | <.0001 |

| Time | −0.002 | 0.14 | −0.02 | .98 |

| Experimental status * | −2.2 | 0.86 | −2.56 | .019 |

| Experimental status × time | −0.40 | 0.17 | −2.32 | .022 |

| Experimental effects on adjustment to home management activities 38% reduction | ||||

| Intercept | 2.6 | 0.37 | 7.04 | <.0001 |

| Time | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.33 | .74 |

| Experimental status * | −0.98 | 0.48 | −2.05 | .043 |

| Experimental status × time | −0.19 | 0.09 | −2.02 | .046 |

| Experimental effects on adjustment to workplace activities | ||||

| Intercept | 3.2 | 0.43 | 8.44 | <.0001 |

| Time | −0.24 | 0.11 | −2.24 | .02189 |

| Experimental status * | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.52 | .607 |

| Experimental status × time | −0.02 | 0.13 | −0.13 | .899 |

Difference in study outcome is estimated at the last time of observation (month 6).

Similar results were observed for the analysis of intervention effects on anxiety scores. Regression models indicated a significant decline in the linear trend (β=−0.40, P=.03) and a lower score of 2.2 units in the experimental group at month 6 (Table 2), P=.02) (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Treatment effects on anxiety.

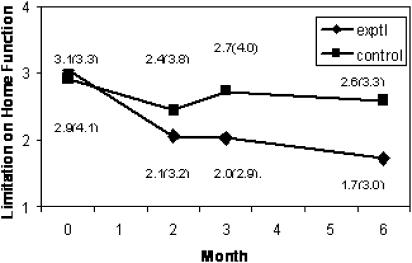

Analysis of the WSAS measures examined whether any improvements in depression and anxiety tracked patient perception of workplace and home management function (Table 2).Fig. 4 Fig. 5 exhibit observed home and workplace measures. Regression modeling indicated that among experimental patients, 6-month improvement rates were significant for home management activities compared with usual care (β=0.2, P=.04) and 1.0 unit lower for experimental than control patients at month 6 (P=.04) that represents ∼40% decrease in limitations with an effect size of 0.3, indicating improvement from moderate-to-minimal impairment. We were unable to detect differences in adjustment to work activities among employed individuals but did observe an overall improvement in both groups over time.

FIGURE 4.

Treatment effects on limitations in home activities.

FIGURE 5.

Treatment effects on limitations in workplace activities.

Comparison of covariance estimates for the growth models with unconditional means estimates showed only modest improvement in goodness of fit for the unconditional growth models (1.3%, 1.5%, and 1.3% of additional variance explained for depression, anxiety, and home function, respectively, P-values <.05 in all cases) with a slightly better fit for conditional growth models (1.9%, 1.5%, and 3.0%, P-values <.05 in all cases).

We also compared variance components associated with patient-level intercepts and slopes across unconditional means, unconditional growth, and conditional growth models for all study outcomes. Relative to unconditional means models for depression, anxiety, and home functions, unconditional growth models were a better fit and explained 13.8%, 10.6%, and 10.8% of variance associated with patient-level intercepts for depression, anxiety, and home function (P-values <.05), while conditional growth analyses explained 16.9%, 23.4%, and 18.4% of the variance for intercepts in the depression, anxiety, and home function models (P-values <.05). Relative to unconditional means models, we observed explanation of additional variance for patient-level slopes for anxiety but not depression or home function analyses. For the unconditional growth model, the addition of time as a fixed effect explained 14.3% (P <.05) of the variance around slopes that increased to 23.8% for the conditional models (P <.05).

We did not observe any improvement in the variance estimates for the workplace function analyses across unconditional means and the growth curve models.

DISCUSSION

This trial demonstrates that a simple, time-limited intervention for cardiac patients at a critical point in the course of their illness produces a significant decrease in symptoms of mood disorders accompanied by improvement in home function. The finding of increased home function suggests that improved mood is associated with desirable functional outcomes but perhaps not with improvements in other outcomes such as mortality as observed in ENRICHD. The estimated effect size of 0.4 for symptoms and 0.3 for home function was higher than we expected as other research 29 on the impact of extended cardiac counseling conducted by nurses reported an effect size of ∼0.2. The greater effect size we observed might be due, in part, to targeting patients during a time of considerable emotional distress. Also, study patients were allowed a 1-month “wash-out” period prior to intervention to allow for resolution of symptoms.30,31

A consideration in assessing the value of the intervention was whether we could observe improvement in function. Adjustment to home management activities decreased similar to those for depression and anxiety, suggesting that functional improvement is associated with improved mood. We were unable to detect improvements in workplace function. In both study arms we observed declines in this measure, and by the end of the intervention at month 2 and thereafter, work impairment levels were identical for 2 groups. It is possible that the financial risk accompanying decrements in workplace performance could serve as an incentive to maintain performance. Alternatively, the lack of effect on work function could be because of a longer lag time for this kind of instrumental variable.

Though not powered to test differences in outcomes by counselor type, we did not detect any trends in difference across provider classes. It is likely that with appropriate training and monitoring of fidelity, the intervention may be appropriate for administration by nurses, social workers, or master's level therapists.

Several limitations need to be made. Although the study was designed as a randomized trial, the causal relationship between function and mood symptoms is unknown. The intervention did not directly target depression and anxiety but focused on adjustment to chronic illness by addressing the concerns and fears associated with recent life-threatening cardiac events. This may have had an effect on adjustment that mediated improvement of symptoms and function. It is likely that the effectiveness we report is bidirectional, and further research with larger samples and longer follow-up would be needed to establish the causal relationships between symptoms and function. The study relied upon self-report that needs to be validated with more objective outcome measures, including workplace performance measures, especially presenteeism and absenteeism. Other potential limitations include generalizability to sites other than urban, tertiary care centers and possible bias because of exclusion of individuals receiving mental health treatment in the period before the index hospitalization.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the promising findings we report merit replication with a larger sample, using more and “harder” measures of symptom, cardiac-specific outcomes and functional improvement. Patient convenience, ease of delivery, and the effectiveness of the intervention suggest that phone-based counseling to help patients adjust to chronic illness may be valuable for patients.

Acknowledgments

We are saddened to have lost Elaine Polishuk, one of the coauthors of this manuscript, who died in the spring of 2005. We dedicate this manuscript to her memory and express our deep gratitude for the many experiences of her intelligence, research abilities, and warmth.

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health: McLaughlin Thomas (Mental Health Services Research Program in Managed Care): MH-56,217-05, 1997, awarded to Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: McLaughlin Thomas. Effectiveness of Telephone Counseling in Managing Depression Associated with Chronic Medical Illness: Grant # 038,765 2001, awarded to Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

REFERENCES

- 1.McGovern PG, Pankow JS, Shahar E, et al. Recent trends in acute coronary heart disease mortality, morbidity, medical care, and risk factors. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:884–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604043341403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenexa RD, Scott-Lenexa JA, Bohlig EM. The cost of depression-complicated alcoholism health-care utilization and treatment effectiveness. J Ment Health Adm. 1993;20(Summer):138–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02519238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reisner C, Gondek K, Musheno M, Menioge S, Mandel M. Depression severity and smoking history, but not age or fev1highly correlate with total charges and medical resource utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. ACCP Annual Meeting Chest. 1998;114(suppl 4):341S. (abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman R, Sobel D, Meyers P, Caudillo M, Benson H. Behavioral medicine, clinical health psychology, and cost offset. Health Psychol. 1995;14:509–18. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.6.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark NM, Becker MH. Theoretical Models and Strategies for Improving Adherence and Disease Management. Handbook of Health Behavior Change. New York: Springer Verlag; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koocher GP, McGrath ML, Gudas LJ. Typologies of non-adherence in cystic fibrosis. J Dev Behav Pediatrics. 1990;11:353–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turk DC, Kerns RD. Health, Illness and Families: A Life-Span Perspective. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Talajic M. Depression following myocardial infarction impact on 6-month survival. JAMA. 1993;270:1819–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bush DE, Ziegelstein RC, Tayback M, et al. Even minimal symptoms of depression increase mortality risk after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:337–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01675-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carney RM, Rich MW, TeVelde A, Saini J, Clark K, Jaffe AS. Major depressive disorder in coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:1273–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90607-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nemeroff CB, Musselman DL, Evans DL. Depression and cardiac disease. Depress Anxiety. 1998;8(suppl 1):71–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patten SB. Long-term medical conditions and major depression conditions in the Canadian population. Canad J Psychiatry. 1999;4:151–7. doi: 10.1177/070674379904400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubzansky LD, Davidson KW, Rozanski A. The clinical impact of negative psychological states: expanding the spectrum of coronary artery disease. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(suppl 1):S10–4. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000164012.88829.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Writing Committee for the ENRICHD Investigators. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3106–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berkman LF, Jaffe AS for the ENRICHD Investigators. The effects of treating depression and low social support on clinical events after a myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104:2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glassman AH, O'Connor CM, Califf RM, Swedberg K, et al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288:701–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Royal College of Physicians. The Psychological Care of Medical Patients: Recognition of Need and Service Provision, Joint Working Party Report of the Royal College of Physicians of London and Psychiatrists. London, UK, Royal College of Physicians, July 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Bronheim HE, Fulop G, Kunkel EI, et al. The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine practice guidelines for psychiatric consultation in the general medical setting. Psychosomatics. 1998;39:S8–30. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3182(98)71317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollin I. Medical Crisis Counseling: Short Term Therapy for Long Term Illness. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koocher GP, Curtis EK, Patton KE, et al. Medical crisis counseling in a health maintenance organization. Prof Psychol: Res Practice. 2001;32:52–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haley J. Problem-Solving Therapy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon G, VonKroff M, Rutter C, et al. Randomised trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ. 2002;320:550–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunkeler E, Meresman J, Hargreaves W, et al. Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Family Med. 2000;9:700–8. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.8.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon GE, Ludman P, Tutty S, et al. Telephone psychotherapy and telephone care management for primary care patients starting antidepressant treatment a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:935–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stoudemire A. Depression in the medically ill. In: Michels R, et al., editors. Psychiatry. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Company; 1991. pp. 1–12. In: ed. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spitzer R, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care the PRIME-MD 1000 Study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston M, Foulkes J, Johnston DW, Pollard B, Gudmundsdottir H. Impact on patients and partners of inpatient and extended cardiac counseling and rehabilitation a controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:225–33. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Coronary heart disease/myocardial infarction depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;91:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M. Major depression before and after myocardial infarction its nature and consequences. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:99–110. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]