Never before in the history of American medicine have the calls for change in the health care system in general, and in internal medicine residency education specifically, been as unrelenting and compelling as in the past several years. One need only consider the recent reports from the Institute of Medicine, the Commonwealth Foundation, and even reports in the New York Times—our health care system is failing to meet the needs of our patients.1–3 This same health care system is also failing to meet the needs of our students and residents. While residency was once an optional course for a physician and usually chosen by those preparing for an academic career,4 today residency experience is as fundamental to the education and preparation of physicians as is undergraduate medical education culminating in the MD degree. Addressing residency reform is as critical to improving our health care system as improving the health care system is to residency reform. They are inextricably linked.

In this issue of the Journal of General Internal Medicine, 3 papers focus specifically on the multiple issues facing internal medicine residency education.5–7 While 1 of the papers is a report from the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) Task Force for Residency Reform, the other 2 focus specifically on the inpatient and the ambulatory settings, respectively. These papers are not simply a recitation of all of the issues we know well, but meaningfully contribute to our understanding of the multiple issues involved and lay out some specific guides to the reform ahead. Both Di Francesco and colleagues, focusing on residency education in the inpatient setting, and Bowen and colleagues, focusing on residency education in the ambulatory setting, point out that even after an extensive review of the literature, we have limited understanding regarding the elements of overall effectiveness of resident education. The SGIM Task Force Report lays out a dozen specific recommendations for reforming internal medicine residency education. These 12 points will serve as a useful guide for the reform.

What next? The 3 papers in this issue, together with a number of initiatives by multiple groups including the Internal Medicine Residency Review Committee's Educational Innovation Project,8 set the stage for the residency reform that many have called for and all of us have talked about. As the authors suggest, it is time for action, not at the margins, but “bold and innovative reforms for the good of our patients and all trainees.”7 This call for action correctly implies that reforming residency education is tightly coupled to addressing the myriad issues facing our overall health care system. Students and residents ideally attain the competencies defined by the ACGME in settings where the aims laid out in the Institute of Medicine's publication, “Crossing the Quality Chasm” are evident. These settings include our academic health centers and teaching hospitals where the systems issues are often the most complex and potentially difficult to break through.

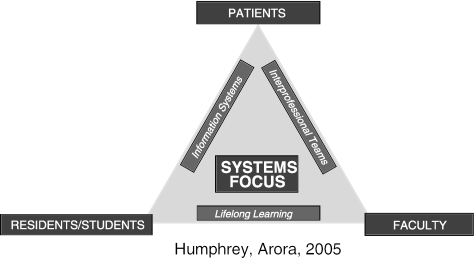

Ultimately, a new paradigm for residency education that is competency based and adheres to the Institute of Medicine's aims for quality improvement will result. Specifically, patients should expect health care that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.9 This vision clearly demands new teaching and evaluation strategies and attention to new elements in the curriculum. Specifically, robust evaluation of competency acquisition must underlie the new model. This is not easy. New methodology must be developed and tested. Medical simulation needs rigorous study and inclusion, when appropriate, in teaching and evaluation. This new model is illustrated in Figure 1, with patients at the apex of the triangle supported by a system built on a foundation of students, residents, and faculty engaged in lifelong learning as part of interprofessional teams utilizing effective information systems to provide medical care.

FIGURE 1.

A new paradigm for medical education.

Whatever model for residency training is ultimately developed, we must seek to preserve the experiential nature of residency and eliminate the redundancy beyond achievement of competency. Without careful attention to this matter, we will inadvertently extend the length and cost of training with potentially deleterious effects on the future supply of new doctors and the costs of our health care system.

We must not be overwhelmed by this daunting task. Instead, we must come together as a discipline and make the changes called for. This means all of us—residents, teaching faculty, program directors, department chairs, the professional societies, the Residency Review Committee for Internal Medicine, and the American Board of Internal Medicine. During 14 years as a residency program director, the most important insights I gained regarding innovations in our own program came from listening carefully to the residents and Chief Residents. Hearing the voices from those in the trenches will go a long way toward helping us get this right. This, combined with focused attention to the principles of health care in the 21st century, will lead us to the best outcome. We have exhaustively reviewed the literature with clear and compelling evidence of the issues, and we even have ideas and strategies for moving forward. Now, we must act. This is not a time for parochialism or political positioning, but for unity on the most important reform we have faced in a generation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blumenthal D. Training tomorrow's doctors, the medical education mission of academic health centers. A Report of the Commonwealth Fund Task Force on Academic Health Issues. April 2002:53–55. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greiner AC, Knebel E, editors. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman J. Awash in information, patients face a lonely, uncertain road. The New York Times. Sunday August 14 2005:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenneth ML. A Time to Heal: American Medical Education from the Turn of the Century to the Era of Managed Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Francesco L, Pistoria MJ, Auerbach AD, Nardino RJ, Holmboe ES. Internal medicine training in the inpatient setting: a review of published educational interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1173–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen JL, Salerno SM, Chamberlain JK, Eckstrom E, Chen HL, Brandenburg S. Changing habits of practice, transforming internal medicine residency education in ambulatory settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1181–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmboe ES, Bowen JL, Green M, et al. Reforming internal medicine residency training: a report from the Society of General Internal Medicine's Task Force for Residency Reform. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1165–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Educational innovation project. Available at http://www.hcfa.gov/stats/nhe-oact/

- 9.Crossing The Quality Chasm. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]