Abstract

D satellite RNA (satRNA) with its helper virus, namely, cucumber mosaic virus, causes systemic necrosis in tomato. The infected plant exhibits a distinct spatial and temporal cell death pattern. The distinct features of chromatin condensation and nuclear DNA fragmentation indicate that programmed cell death is involved. In addition, satRNA localization and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling show that cell death is initiated from the infected phloem or cambium cells and spreads to other nearby infected cells. Timing of the onset of necrosis after inoculation implicates the involvement of cell developmental processes in initiating tomato cell death. Analysis of the accumulation of minus- and plus-strand satRNAs in the infected plants indicates a correlation between high amounts of minus-strand satRNA and tomato cell death.

INTRODUCTION

Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) is an isometric plant virus with a tripartite plus-sense RNA genome (Palukaitis et al., 1992). Some strains of CMV harbor satellite RNAs (satRNAs)—small, linear molecules ranging from 332 to 405 nucleotides long. The satRNAs are dependent on CMV for their replication, encapsidation, and dispersion, but they are not necessary for the life cycle of the virus. They can attenuate or exacerbate the symptoms induced by the helper viruses in specific plant hosts. For example, D-satRNA, B-satRNA, and WL1-satRNA induce necrosis, chlorosis, and attenuation, respectively, in infected tomato plants in the presence of any CMV helper virus. In tobacco, however, D-satRNA and WL1-satRNA attenuate symptoms, whereas minor nucleotide sequence variants of the B-satRNA either attenuate symptoms or induce chlorosis in a helper virus–specific manner (reviewed in García-Arenal and Palukaitis, 1999).

D-satRNA (335 nucleotides long) induces a lethal systemic necrosis in tomato that has been reported as epidemic in France, Italy, and Spain (Kaper and Waterworth, 1977; Jordá et al., 1992). The molecular and cellular mechanisms of the disease, which can cause a catastrophic reduction in tomato production, remain unknown, although the sequences in D-satRNA responsible for the lethal necrosis have been determined (Sleat and Palukaitis, 1990; Sleat et al., 1994). By using in vitro and in vivo analyses of its secondary structure, researchers have correlated a helix and a tetraloop region near the 3′ end of the satRNA with the necrotic syndrome (Bernal and García-Arenal, 1997; Rodríguez-Alvarado and Roossinck, 1997). For some specific CMV and satRNA combinations, RNA 2 of CMV has been shown to be involved in determining pathogenicity (Sleat et al., 1994). Recently, however, the minus-strand D-satRNA expressed from a potato virus X vector was shown to induce similar necrosis in tomato, thereby excluding the specific role of CMV in the pathogenicity of D-satRNA, except for its function as a helper virus in the host plants (Taliansky et al., 1998).

The conspicuous symptom of tomato plants infected by D-satRNA and CMV is cell death, the cause of the lethal systemic necrosis (Kaper and Waterworth, 1977). In recent years, plant cell death has been studied extensively (Dangl et al., 1996; Jones and Dangl, 1996; Greenberg, 1997; Pennell and Lamb, 1997). Programmed cell death (PCD) was first defined on the basis of the predictable and distinguished cell morphology in animal cells (Kerr et al., 1972). Some kinds of plant cell death share features that are similar to animal PCD or apoptosis, such as the cell death during cell differentiation of tracheary elements, somatic embryogenesis, and leaf senescence. Similarity also exists in the cell death during the interactions between plants and pathogens or environmental factors (Pennell and Lamb, 1997; Danon and Gallois, 1998; Yen and Yang, 1998; Gao and Showalter, 1999; Navarre and Wolpert, 1999; Stein and Hansen, 1999).

PCD is an ordered cell-suicide process. It includes the condensation, shrinkage, and fragmentation of the cytoplasm and nucleus and also the fragmentation of nuclear DNA into ∼50-kb fragments or, in some cases, into oligonucleosome lengths (180 bp and multiples thereof) (Ellis et al., 1991). However, not all of these events occur in every PCD situation. The hallmark of PCD is nuclear DNA fragmentation. The DNA fragments can be visualized by using the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) technique in cell sections. A laddered pattern of total DNA also can be visualized after agarose gel electrophoresis (Gavrieli et al., 1992). When the dying cell shows condensation of the chromatin in the nucleus, breakage of the cytoplasm and nucleus into small, sealed packets, and processing of the nuclear DNA at nucleosome linker sites, this process is termed apoptosis.

Animal PCD or apoptosis has very conserved cell death execution machinery and multiple regulatory pathways. To date, not all aspects of plant PCD are understood. Some morphological features of cell death in plants are similar to the features of animal PCD. Some biochemical events are also similar, including calcium flux, membrane exposure of phosphatidylserine, and activation of specific cysteine proteases or aspartate protease (Drake et al., 1996; May et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1996b; Chen and Foolad, 1997; Solomon et al., 1999).

The hypersensitive response (HR) is the most well-studied cell death in plants. A result of interactions of plants and incompatible pathogens, it causes the rapid collapse of the infected tissue that can lead to resistance. PCD is involved in the HR, as shown by genetic, biochemical, and cell biological studies (Dangl et al., 1996; Greenberg, 1997; Pennell and Lamb, 1997). Cell death is often a feature of disease symptoms during the susceptible interaction between plants and necrotrophic pathogens. Usually, the cells are killed by the action of pathogen-derived toxins or else die at a late stage after infection. However, cell death is not well understood in most cases. In Alternaria stem canker disease of tomato caused by the toxin of the fungus (Alternaria alternata f sp lycopersici), cell death in the toxin-treated protoplasts and leaflets has the morphological characteristics of apoptosis (Wang et al., 1996a). In victoria blight of oats, cell death induced by victorin also has some apoptotic features (Navarre and Wolpert, 1999).

Here, we studied the cell death of the lethal systemic necrosis of tomato induced by D4-satRNA with its helper virus, CMV. Cell death occurs at a late stage of infection, making this an excellent system for studying the interaction between host cells and viruses. The satRNA molecule has a well-studied sequence and structure, and this lethal systemic necrosis has a strong host-specificity component. The biological characteristics of cells during cell death were analyzed, and the formation of systemic necrosis with a specific temporal and spatial cell death pattern was assessed. The correlation of vascular cell development and high amounts of minus-strand satRNA with the initiation of tomato cell death are shown.

RESULTS

D4-satRNA–Induced Systemic Necrosis

Tomato plants (cv Rutgers) were inoculated on the first true leaves of seedlings at the three-leaf stage with RNA from the Fny strain of CMV (Fny-CMV) and D4-satRNA, Fny-CMV RNA alone, or viral RNA dilution buffer. After ∼10 days, typical mild mosaic symptoms appeared on the systemically infected leaves of Fny-CMV–inoculated tomato plants (Figure 1B). However, epinasty of the leaflets and systemic necrosis occurred in the plants infected by Fny-CMV and D4-satRNA (Figures 1C and 1D). Necrosis first occurred on the second node below the meristem and spread upward and downward along one side of the stem and the midrib of the leaflet (Figure 1D). The mock-inoculated tomato plant showed no symptoms (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Symptoms in Systemic Virus–Infected Tomato at 10 DPI.

(A) Mock-inoculated plant.

(B) Fny-CMV–inoculated plant showing mild mosaic symptoms.

(C) and (D) Fny-CMV– and D4-satRNA–inoculated plant showing systemic necrosis and leaf epinasty at the apex. (D) provides a magnified view of the apex of the plant from (C), showing necrosis in the petiole and stem (boxed).

Light Microscopy of Fny-CMV and D4-satRNA–Infected Tissues and Cells

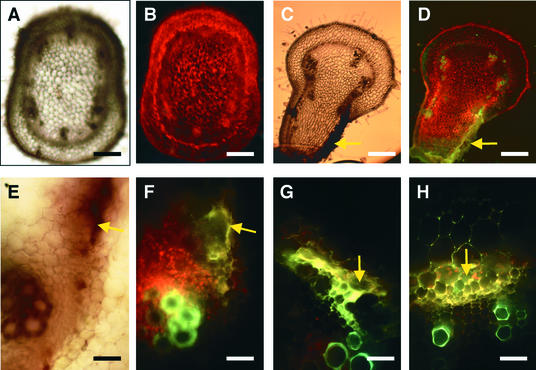

The stems above the inoculated leaves were cut, sectioned, and observed by light and fluorescence microscopy, shown in Figure 2. One side of the stem in the area of the second node below the meristem exhibited symptoms of necrosis (Figure 2C), and the necrotic cell walls emitted yellow fluorescence when exposed to blue light (Figures 2D and 2F to 2H). The xylem cells ordinarily emit green autofluorescence (Figures 2D and 2F to 2H), and the healthy cells emit red autofluorescence (Figures 2B, 2D, and 2F). The first signs of necrosis in stems of infected tomato plants at 9 and 10 days postinoculation (DPI) were observed in the prevascular cells close to the meristem (data not shown) or in some phloem or cambium cells along one side of the stem (Figures 2E and 2F). Necrosis then spread to other nearby cells, such as the outside cortical (Figure 2G) and inside pith (Figure 2H) cells. No necrotic cells were observed in the plants inoculated with Fny-CMV only (Figures 2A and 2B) or in the mock-inoculated plants (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Fresh Stem Sections from the Second Node below the Meristem of Virus-Infected Tomato Plants.

Bright-field illumination ([A], [C], and [E]) shows nonnecrotic tissues (A) and brown necrosis (arrows in [C] and [E]). UV illumination ([B], [D], and [F] to [H]) shows red autofluorescence from chlorophyll ([B], [D], and [F]), green autofluorescence in the xylem cells ([D] and [F] to [H]), and yellow autofluorescence from necrotic cells (arrows in [D] and [F] to [H]). Necrotic cells are cambium and external phloem cells ([E] and [F]), cortical and vascular cells (G), and pith and phloem cells (H). Plants were infected with Fny-CMV ([A] and [B]) or with Fny-CMV and D4-satRNA ([C] to [H]).

(A) to (D) Whole-stem sections at 10 DPI.

(E) and (F) Cambium layer and phloem cells at 9 DPI.

(G) Cortical cells at 10 DPI.

(H) Pith cells at 10 DPI.

;

;  .

.

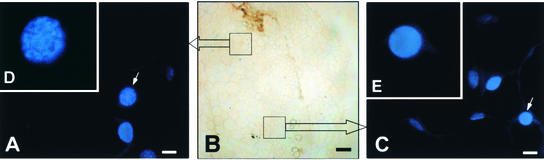

Chromatin condensation is a typical feature of apoptosis. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) dihydrochloride, a UV-excitable dye that can specifically bind double-stranded DNA in the nucleus, was used to assess the structure of the chromatin, as shown in Figure 3. The stems from infected and mock-inoculated tomato plants were fixed, sectioned, stained with DAPI dihydrochloride, and observed under a fluorescence microscope. No abnormal structures were apparent in the nuclei of the mock-inoculated or Fny-CMV–infected tomato (data not shown). Within the stems of plants infected with Fny-CMV and D4-satRNA, necrosis occurred along one side (Figure 3B). The nuclei in the pith cells adjacent to the collapsed dead cells along the necrotic side of the stem showed condensed or marginalized chromatin (Figure 3A), whereas the nonnecrotic side of the stem displayed uniform fluorescence, which is characteristic of normal, noncondensed nuclear DNA (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

DAPI Staining of Cell Nuclei from Stem of Tomato Plant Infected with Fny-CMV and D4-satRNA.

Stained nuclei show condensed chromatin ([A] and [D]) or uniform chromatin ([C] and [E]).

(A) and (B) Nuclei from the necrotic side of the stem tissue (the upper box shown in [B]) under bright-field microscopy.

(C) Nuclei from the nonnecrotic side of the stem tissue (the lower box shown in [B]).

(D) and (E) Magnified nuclei indicated by the arrows in (A) and (C).

;

;  ;

;  .

.

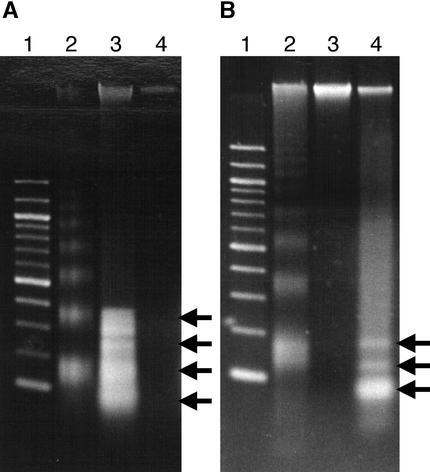

Detection of Nuclear DNA Fragmentation

Nuclear DNA fragmentation often occurs with PCD and can be detected by the banding pattern of total DNA seen after agarose gel electrophoresis and by TUNEL analysis used to detect free 3′-OH groups in DNA in situ. Total DNA was extracted from prenecrotic, necrotic, and nonnecrotic tissues of the infected tomato plants and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, with visualization by ethidium bromide, shown in Figure 4. Prenecrotic tissue was from tomato plants infected with Fny-CMV and D4-satRNA before the onset of visual symptoms, generally at ∼8 DPI. DNA fragments of ∼180 and 360 bp (one or two nucleosome lengths) were observed in the total DNA extracted from prenecrotic and necrotic tissues. Additional bands of ∼100, 150, and 300 bp were also detected. No conspicuous degradation was found in the nonnecrotic tissues (Figures 4A and 4B).

Figure 4.

Total DNA from Tomato Tissues Infected by Fny-CMV and D4-satRNA.

(A) and (B) Lanes 1 contain the 1-kb DNA ladder (Gibco); lanes 2, victorin-treated oat leaf DNA ladder marker.

(A) Lane 3 contains prenecrotic tissue at 9 DPI; lane 4, nonnecrotic tissue at 9 DPI.

(B) Lane 3 contains nonnecrotic tissue at 10 DPI; lane 4, necrotic tissue.

Arrows from top to bottom indicate 360, 300, 180, and 100 bp (A) or 180, 150, and 100 bp (B), respectively.

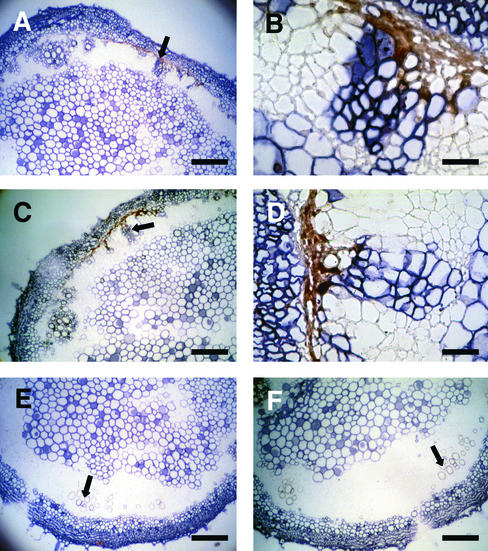

The TUNEL procedure was performed with serial sections of tomato stems; results are shown in Figure 5. Sections from Fny-CMV–infected plants were treated with DNase I as a positive control, and all the nuclei were stained using the TUNEL procedure (Figure 5B). In the experimental sections, a positive signal was found in a few cells along one side of the stem in the plants infected by Fny-CMV and satRNA but not in mock- or Fny-CMV–inoculated tomato plants (Figure 5). No positive signal was noted in sections from which the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase enzyme was omitted (data not shown).

Figure 5.

TUNEL Assay of Longitudinal Sections from the Second Node of Infected Tomato Stems.

(A) Fny-CMV–infected tomato.

(B) Fny-CMV–infected tomato treated with DNase I (positive control).

(C) and (D) Tomato infected with Fny-CMV and D4-satRNA at 9 DPI (prenecrotic stage), with (D) showing a magnified view of a portion in (C). Arrows in (D) indicate TUNEL-positive nuclei with nuclear DNA fragmentation.

The dark green fluorescence in (A) to (D) is the autofluorescence of nuclei in the normal cells.  ;

;  .

.

SatRNA Concentrations and Localization in Prenecrotic and Necrotic Tissues

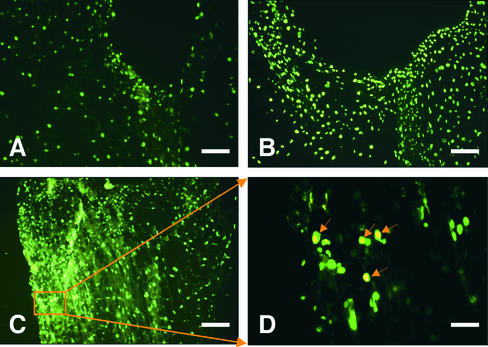

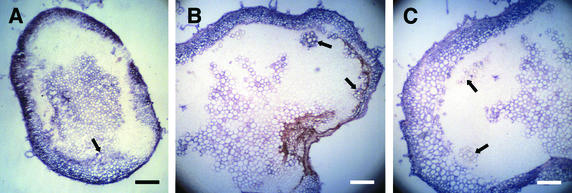

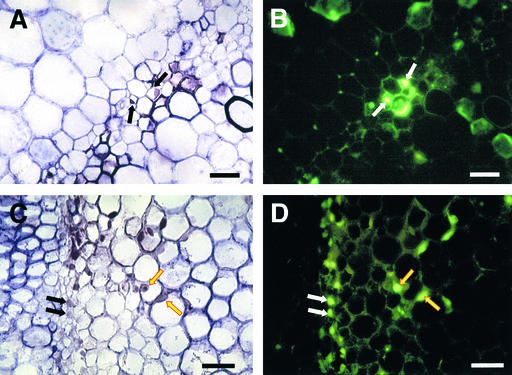

Cross-sections of tomato stems used for TUNEL were annealed with nonradioactive minus- or plus-strand-specific probes of satRNA, shown in Figures 6 to 8. The localization patterns of D4-satRNA in tissues were observed by bright-field microscopy, and the TUNEL signal was observed under fluorescence optics. In prenecrotic or necrotic stems, the plus strand of satRNA was distributed in most of the cells outside of the vascular cylinder and in some vascular bundles and nearby pith cells (Figures 6A to 6C). The localization patterns of plus- and minus-strand satRNA in the prenecrotic (data not shown) and necrotic stems were the same (Figure 7). Necrosis appeared at the side of the stem with plus- or minus-strand satRNAs in the vascular bundle cells (Figures 6B and 7A to 7D). There was no satRNA in the vascular cells at the nonnecrotic side of the stem (Figures 6C, 7E, and 7F).

Figure 6.

Localization of Plus-Strand D4-satRNA in Stems of Infected Tomato.

(A) Prenecrotic tissue at 9 DPI.

(B) and (C) Stem section at 10 DPI, showing the necrotic side (B) and the nonnecrotic side (C).

Arrows indicate vascular bundles with positive signal for satRNA ([A] and [B]) and without signal (C).  .

.

Figure 8.

In Situ Hybridization for satRNA and TUNEL Analysis in Fny-CMV– and D4-satRNA–Infected Stem Tissue.

(A) and (B) Portion of the stem cross-section containing external phloem cells at 9 DPI (prenecrotic).

(C) and (D) Portion of the stem cross-section containing phloem and pith cells at 10 DPI (necrotic).

The cells stained in brownish purple are satRNA-containing cells. (B) and (D) were visualized under a fluorescence field exposed in blue light. Arrows indicate the cells positive both for satRNA and TUNEL. Black and white arrows indicate phloem cells ([A] to [D]); yellow arrows indicate pith cells ([B] and [D]).  ;

;  (

( .

.

Figure 7.

Distribution of the Plus- and Minus-Strand D4-satRNAs in Serial Sections of Necrotic Stem.

(A) to (D) Necrotic side of the stem. The same positive-staining vascular bundle indicated by the arrows in (A) and (C) is magnified in (B) and (D).

(E) and (F) Nonnecrotic side of the stem. The arrows indicate a nonstaining vascular bundle.

Plus strands are shown in (A), (B), and (E); minus strands are shown in (C), (D), and (F).  ;

;  .

.

Staining by using the TUNEL procedure revealed nuclear DNA fragmentation, starting from the infected vascular cells in the stems in the area of the second node, including primarily the external phloem cells (Figures 8A and 8B), the internal phloem cells, and a few vascular contact cells in the prenecrotic tissue (data not shown). Later, some nearby infected cells (vascular, pith, and cortical cells) became TUNEL positive, as seen in the staining of necrotic tissue (Figures 8C and 8D).

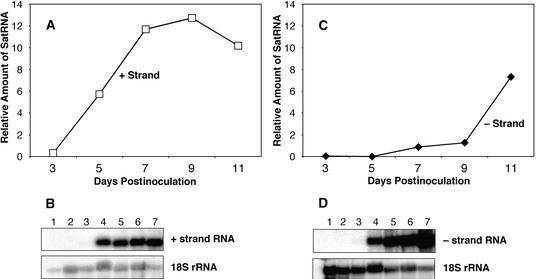

Total nucleic acids were extracted from the apices in the area of the second node below the meristem of infected plants over a period from 3 to 11 DPI; they were analyzed by RNA gel blotting (Sambrook et al., 1989) with strand-specific probes. The accumulation of plus-strand satRNA increased rapidly and remained high throughout this period, whereas the accumulation of minus-strand satRNA in this tissue was relatively slow until the initiation of necrosis, at which time the minus-strand satRNA accumulated rapidly (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

RNA Gel Analysis and Quantitation of Relative Amounts of Plus- and Minus-Strand D4-satRNAs at Apices of Infected Tomato Plants.

(A) and (B) Plus-strand satRNA.

(C) and (D) Minus-strand satRNA.

In (B) and (D), lanes 1 contain the total RNAs from mock-inoculated plants; lanes 2, those from the Fny-CMV–infected plants; and lanes 3 to 7, those from the Fny-CMV– and D4-satRNA–infected plants at 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 DPI, respectively.

Inoculation Tests of the Necrotic Initiation Sites in Tomato Plants at Different Developmental Stages

Necrosis in tomato has a regular temporal and spatial pattern of cell death under the usual greenhouse conditions used for plant propagation. When the first leaves of tomato seedlings at the three-leaf stage were inoculated, cell death usually started with the prevascular cells (or with the young vascular cells) along one side of the stem in the area of the second node, indicating a role for developmental processes of the infected cell during necrosis. When the first leaves of tomato plants at different developmental stages (from two-leaf to eight-leaf stages) or when leaves at different positions from five-leaf-stage tomato plants were inoculated, the temporal and spatial patterns of necrosis shifted; nonetheless, in all the cases tested, necrosis initiated at the stem in the area of the second node below the meristem (Table 1). Necrosis was also observed starting from the veins or midribs of inoculated leaflets, the second or third leaflets above the inoculated leaves, and the stems below the inoculated leaves when the plants were inoculated at later developmental stages (five-leaf to eight-leaf stages).

Table 1.

Inoculation Test of the Necrotic Initiation Sites

| Developmental Stage of Inoculated Plants | Position of Inoculated Leaves | DPI When Necrosis Appears | Secondary Sites of Necrosisa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two- to three-leaf stage | First | 6–10 | None |

| Three- to four-leaf stage | First | 9–12 | None |

| Five- to six-leaf stage | First | 12–16 | Inoculated leaflet and petiole and stem below inoculated leaf |

| Seven- to eight-leaf stage | First | 15–19 | Inoculated leaflet; and second or third leaflets above the inoculated leaf, and surrounding stem |

| Five-leaf stage | Third | 12 | Inoculated leaflet |

| Fourth | 10–12 | Inoculated leaflet |

All plants had primary initiation sites at the stem in the area of the second node below the meristem.

DISCUSSION

PCD Is Involved in the D4-satRNA–Induced Systemic Necrosis in Tomato

Host cell death is one of the consequences of plant–pathogen interactions. It can lead to either necrosis disease (Wang et al., 1996a; Navarre and Wolpert, 1999) or disease resistance, such as extreme resistance or systemic acquired resistance (Greenberg et al., 1994; Mittler et al., 1995; Bendahmane et al., 1999). Disease resistance usually results from a response to incompatible pathogens. During extreme resistance, the inoculated cells commit suicide as well as disrupt the replication of the pathogen or promote the degradation of viral RNA. In the HR resulting in systemic acquired resistance, not all of the infected cells die, and the HR type of viral resistance is thought to be a tissue-related phenomenon requiring cell-to-cell contact (Graca and Martin, 1976). Necrosis disease is usually caused by compatible pathogens that use dead tissue as a nutrient source. The cells are either killed by the action of pathogen-derived toxins or are induced to die at a late stage of infection.

Necrosis caused by viral pathogens is unusual because the pathogen is a biotroph, which means the necrosis is suicidal for the pathogen. In no known case could the satRNA be considered a mutualist for the virus; rather, it behaves like a mutualist for the plant. Perhaps the satRNA originated as a defense molecule in some unknown host plant, developed the ability to be replicated by the virus, and evolved into a selfish RNA, parasitizing the viral machinery. Clearly, the satRNA did not evolve in a host such as tomato, where it ultimately destroys both itself and its helper virus. These interactions most likely represent the accidental triggering of the cell-death pathway by the satRNA.

Whether the host cells utilize similar molecular or cellular mechanisms in processing the cell death induced by diverse pathogens that have different effects on host plants is not known. Studies show that the HR is uncoupled from the resistance mechanism in at least some cases, indicating that the host responses of cell death and resistance may use different pathways (del Pozo and Lam, 1998; Yu et al., 1998; Bendahmane et al., 1999). PCD is involved in some cases of both pathogen-induced resistance and disease cell death (Greenberg et al., 1994; Ryerson and Heath, 1996; Wang et al., 1996a, 1996b; Kosslak et al., 1997; Navarre and Wolpert, 1999). Here, cell death occurring during the systemic necrosis induced by D4-satRNA shares cellular features similar to those of PCD. The nuclear chromatin in the cells undergoing cell death was obviously condensed. Nuclear DNA fragmentation was detected in situ by the TUNEL procedure. The temporal and spatial pattern of the nuclear DNA fragmentation in the tissue matched the necrosis pattern, appearing along one side of the stem when the tomato plants were inoculated on a single leaf. Although the complete typical DNA ladder of apoptosis was not observed in total DNA, the DNA fragments of ∼180 and 360 bp are consistent with fragments being one and two nucleosomes long. Moreover, detection of the DNA ladder may be diffi-cult for technical reasons (Groover et al., 1997; Gao and Showalter, 1999). The cells are not synchronized in intact tissues during the development of systemic necrosis. In this study, only a few cells were processing nuclear DNA fragmentation at the prenecrotic stage, whereas the later stage showed substantial DNA degradation (Figure 4). In addition, using this system, some other endonucleases may have been activated with specific digestion sites that produce the smaller 100- and 150-bp fragments. In virus-induced PCD in plants, no typical DNA ladders of apoptosis have been found; however, Ca2+-activated DNA endonuclease activity has been detected, and an endonuclease implicated in DNA fragmentation during the HR has been purified from tobacco infected with tobacco mosaic virus (Mittler and Lam, 1995, 1997).

The similarities of cell morphology during pathogen-induced resistance and disease cell death suggest that common mechanisms might exist in the execution of cell death but might have multiple, distinct signaling pathways. The HR may result from a PCD pathway that is induced by the specific interaction between pathogen avirulence gene products and host resistance gene products, but the recognition of pathogens and the activation of the PCD pathway are poorly understood. Alternaria tomato canker disease results from the A. a. lycopersici toxin, which can also induce apoptosis in monkey kidney cells, but the molecular mechanism in tomato has not been determined (Wang et al., 1996a). The oat blight disease induced by the toxin victorin involves the specific cleavage of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and may interact with senescence mechanisms (Navarre and Wolpert, 1999). The types and number of pathways, whether they are activated separately or have cross-talk, and how they converge to result in the similar cell morphology and ultimately cell death are still unknown.

The generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been suggested as a key trigger or mediator to PCD accompanying the HR (Jabs et al., 1996; May et al., 1996; Mittler et al., 1996; Bestwick et al., 1997; Lamb and Dixon, 1997; Desikan et al., 1998). Hydrogen peroxide also accumulates in lettuce leaf tracheary elements (Bestwick et al., 1997) and senescing pea leaves (Pastori and del Río, 1997). Thus, ROS might be a general trigger for PCD in plants, although they may be insufficient to induce PCD (Glazener et al., 1996). Here, hydrogen peroxide correlated closely with the D4-satRNA–induced rapid cell death (data not shown), which suggests the possibility of a common pathway for hydrogen peroxide to induce host cell death during both the incompatible and susceptible reactions.

The accumulation of hydrogen peroxide involves the activation of a plasma membrane–associated NAD(P)H oxidase (Jabs et al., 1996) and the inhibition of catalase expression and suppression of cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase during the response of plants to pathogens (Chamnongpol et al., 1996; Takahashi et al., 1997; Mittler et al., 1998). Recently, cysteine proteases were found to be activated by oxidative stress in soybean cells and inhibition of cysteine proteases could block PCD (Solomon et al., 1999). Although specialized cysteine proteases known as caspases are active during animal apoptosis, no caspase has yet been identified in plants; however, caspase activity has been detected in tobacco mosaic virus–induced HR in tobacco, and caspase inhibitors can block PCD induced by bacteria in tobacco (del Pozo and Lam, 1998).

A Large Amount of Minus-Strand satRNA Is Correlated with the Tomato Systemic Necrosis

The decisive role of minus-strand D-satRNA in inducing necrosis in tomato was shown by its expression from a potato virus X vector (Taliansky et al., 1998). Here, the localization pattern of the minus strand was the same as that of the plus strand in the tissues that were processing cell death. The satRNA was seen in the prenecrotic tissues ∼1 week before the onset of necrosis (data not shown). Therefore, the spatial distribution of viral RNAs is insufficient to account for the specific cell death pattern in tomato. Taliansky et al. (1998) suggested that a certain threshold of minus-strand D-satRNA might be required in the syndrome in tomato. In the present study, RNA gel blot analysis shows a large amount of minus-strand satRNA accumulating during necrosis and a change in the ratio of minus- and plus-strand satRNAs occurring during the initiation of necrosis. The accumulation of minus-strand satRNA increased rapidly during the rapid spread of cell death. The same analysis was performed for the infected plants when the plants were inoculated at different leaf stages. Although the temporal patterns for the appearance of systemic necrosis were shifted, the tendency of the minus-strand satRNA accumulation was similar in all cases tested (data not shown). These results support the important role of the amount of minus-strand satRNA in the formation of the specific temporal pattern of cell death, although double-stranded satRNA possibly is also involved in the pathogenesis. The amounts of minus- or plus-strand satRNAs in nonnecrotic tissues show a timing tendency similar to that in the tissue in which PCD is initiated (data not shown). Therefore, the initiation of cell death not only involves the amount of minus-strand satRNA in the tissue but also is associated with the cell type and developmental stage, as shown by the results from the inoculation tests and in situ hybridization.

Developmental Regulation Is Involved in Initiation of PCD Induced by D4-satRNA

Tomato plants infected with CMV and D-satRNA were characterized by necrosis throughout the plants at the late stage of infection (Kaper and Waterworth, 1977). The extent of necrosis in the plants was influenced by environmental factors, such as temperature, and infected plants at a particular developmental stage were more susceptible to cell death (Kaper et al., 1995). In this study, our inoculation test results and fresh tissue sections show that necrosis appeared in a specific temporal and spatial pattern that varied depending on the developmental stage of the inoculated leaf and the tomato plant. Necrosis started from the vascular cells in the area of the second node below the meristem and spread very rapidly to the meristem, the petiole of the leaflet, and other nearby cells in the stem below the node. This development of necrosis indicates that the cells in the area of the second node are susceptible to cell death. When the plants were inoculated at approximately the five- to eight-leaf stage, the necrosis, in addition to sharing a common initiation site, also started from several secondary sites, including the petioles of the inoculated leaflet and of the second or third leaflet above the inoculated leaf and in the stems below those leaflets. Newly formed vascular cells in the secondary growth of the tomato stem are produced at those sites, and these may be in a physiologic state similar to the vascular tissue in the area of the second node.

The vascular cells in the stem became necrotic first, as observed in the fresh tissue sections. Sections double-labeled for D4-satRNA localization and nuclear DNA fragmentation initially were found only in the developing vascular cells, principally the phloem cells.

After the death of these vascular cells, some nearby infected cells were triggered very quickly to PCD. The rapid spread of the cell death caused a visible brown necrosis that developed only along the side of the stem or petiole that contained satRNA in the vascular bundles. Hence, the spatial pattern of necrosis is associated with both the development of vascular cells and satRNA localization in the tissues. In the tomato fruit necrosis caused by another CMV satRNA, the necrosis was thought to be caused by incomplete differentiation of the vascular tissue of the fruit stalk (Crescenzi et al., 1993). These results indicate that satRNA might alter the normal vascular cell development. PCD is involved in vascular cell differentiation such as xylogenesis (Fukuda, 1997). Perhaps D-satRNA interacts with the developmental regulation pathway in the vascular cells in the area of the second node below the meristem and induces PCD similar to that involved in xylogenesis or senescence.

In conclusion, our study shows that in the complicated trilateral interaction among D-satRNA, helper virus, and tomato, PCD is involved in the lethal systemic necrosis disease. The infected prevascular cells close to the meristem and the phloem and cambium cells in the area of the second node below the meristem may be more susceptible to the accumulation of minus-strand satRNA and thus may initiate the process of PCD, which leads to the rapid death of the other nearby infected cells. This system provides us with an opportunity to study both the molecular regulation of PCD in plants and the potential role of RNA in the induction of PCD and may ultimately lead to development of improved plant resistance to the lethal necrosis of tomato induced by satRNA.

METHODS

Viruses, Plants, and Plant Inoculations

Plasmid pDsat4 was described previously (Kurath and Palukaitis, 1989). Plasmid pDsat4SP6 was generated by polymerase chain reaction amplification of pDsat4 with the primers 5′-GGGAATTCATTT-AGGTGACACTATAGTTTTGTTTG-3′ and 5′-GGGGTCTAGACC-CGGGTCCTG-3′ (satellite RNA [satRNA] sequences are shown in boldface). The amplified product was digested with EcoRI and XbaI (underlined in the respective primers) and cloned into the analo-gous sites in pBluescript KS+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Linearization of the resulting clone with SmaI and transcription with bacteriophage SP6 polymerase (Ambion, Austin, TX) to generate precise satRNA transcripts were then possible. Zucchini squash (Cucurbita pepo cv Elite) was infected by the transcripts generated in vitro from cDNA clones of the three viral RNAs (Roossinck et al., 1997) and pDsat4SP6. Virus was purified, and viral RNAs were extracted by the protocol previously described by Roossinck and White (1998).

Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum cv Rutgers) seedlings used for inoculation were grown to two- to eight-leaf stages under greenhouse conditions. Fny–cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) RNAs or Fny-CMV and satRNAs were inoculated onto the first leaves of tomato at a total concentration of 500 μg/mL in 50 mM Na2HPO4. The control plants were inoculated with inoculation buffer. In the inoculation test, eight seedlings were inoculated at each developmental stage, from two- to eight-leaf. All of the infected plants were kept under greenhouse conditions.

The nonradioactive and radioactive RNA probes were generated from pDsat4 and pDsat4SK. Plasmid pDsat4SK, generated by inserting the full-length cDNA of D satRNA sequences from pDsat4 (cutting with SmaI and BamHI) into the pBluescript SK+ vector, was used to generate the minus-strand probe by T7 RNA polymerase.

Light Microscopy of Stem Sections

When the symptoms in tomato induced by Fny-CMV with satRNA first appeared, stems of infected and control plants were excised and then sectioned serially by hand with a razor blade. All of the sections were examined under a Nikon Microphot photomicroscope equipped with filters specific for epifluorescence and fluorescein isothiocyanate, and photographs were taken using Kodak 160T film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Isolation of Nuclear DNA for Fragmentation Analysis

Approximately 100 mg of the nonnecrotic, prenecrotic, and necrotic tissues from tomato plants infected by Fny-CMV and D4-satRNA were harvested, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground; the powder was then transferred to 750 μL of extraction buffer (0.1 M Tris, 50 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl, and 1% SDS), followed by vortex mixing and incubation at 65°C for 20 min. To this was added 250 μL of 5 M potassium acetate; the contents of the tubes were mixed well, incubated on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 18,000g for 10 min in a microcentrifuge. The supernatant was removed to a fresh tube. An equal volume of isopropanol was added to the supernatant, and the mixture was centrifuged at 18,000g for 5 min. The precipitates were dissolved in 100 μL of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (Sambrook et al., 1989) and extracted with TE buffer–saturated phenol:chloroform (1:1 [v/v]). The nucleic acid was reprecipitated with one volume of isopropanol. The total nucleic acid was dissolved in 50 μL of TE buffer containing 100 μg/mL RNase A (Sigma) and incubated for 20 min. The DNA was analyzed on 1.5% agarose gel in Tris-acetate/EDTA electrophoresis buffer (Sambrook et al., 1989) and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

Fixation, Dehydration, and Embedding of the Tissues

Just before and after necrosis was visible in the tomato plants infected by Fny-CMV and D4-satRNA, the stem or meristem tissues were cut, as were the counterparts from Fny-CMV– and mock-inoculated plants. The excised tissues were placed in glass vials containing a fixative solution of 3% paraformaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4. The tissues were microwaved for 3 sec and allowed to set in fixative for 3 to 4 hr at room temperature. After fixation, the tissues were washed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer three times and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions consisting of 20:80, 40:60, 60:40, 80:20, 95:5, and 100:0 ethanol in water (v/v), followed by infiltration in low-melting-point wax (Vitha et al., 1997). The components of the wax were nine parts polyethylene glycol distearate and one part 1-hexadecanol (Sigma). Infiltration was done at 37°C by transferring tissues to a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of wax and ethanol for 4 hr, a 2:1 (v/v) mixture overnight, and to pure wax for 8 hr. The tissues were transferred into plastic weighing boats at room temperature and then embedded.

Nuclear Staining and Terminal Deoxynucleotidyltransferase-Mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling

The embedded tissues were sectioned with a microtome (Reichert Jung, model 2050, Cambridge Instruments, Heidelberger) to be 10 μm thick and transferred to slides coated with 0.1% polylysine. The serial sections on the slides were treated with 5% acetone and 2% 1-butanol three times, followed by serial solutions of concentrated ethanol in 20 mM Tris base, 0.5 M NaCl, and 0.85% Tween 20, pH 7.5. The slides were rinsed with H2O and PBS, treated with proteinase K for 30 min at 37°C, washed in 0.2% glycine PBS solution for 2 min, rinsed with PBS and water several times, and finally air dried.

For 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining, the sections were incubated for 20 min with a 0.5-μg/mL solution of the stain in H2O, washed with H2O, and mounted with a solution of 50% glycerin in H2O. The stained nuclei emitted blue fluorescence when excited by UV light.

An in situ cell death detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim) was used to detect the nuclear DNA fragmentation according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The air-dried sections were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 hr with the reaction mixture containing terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase and fluorescein-labeled dUTP and then were rinsed with PBS. Some slides were sealed by mounting solution with 50% glycerine and 1% p-phenylenediamine in H2O. Some were used for subsequent RNA in situ hybridization. The positive signal showed the bright green fluorescence excited by blue light. All the photographs were taken with 1600T film by microscopic photography with a Nikon Microphot-FX camera.

RNA in Situ Hybridization for Detecting the Localization of Minus- and Plus-Strand satRNA in Tissues

Previously published protocols for RNA in situ hybridization (Coen et al., 1990; Ding et al., 1996) were modified and used here for detecting the localization of plus-strand or minus-strand satRNA. The probes of plus- and minus-strand satRNAs were labeled by transcription of pDsat4 or pDsat4SK with the inclusion of digoxygenin-UTP. The in vitro hybridization buffer contained salts (0.3 M NaCl, 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 0.01 M Na3PO4, and 5 mM EDTA), 50% deionized formamide, 1.25 mg/mL tRNA, Denhardt's solution (0.002 g/L each Ficoll 400, polyvinylpyrrolidone, and BSA), and 12.5% dextran sulfate. The probes were denatured at 80°C for 5 min and were kept in 50% formamide solution. The probes were mixed with hybridization buffer and loaded on the sections.

The sections were incubated at 50°C overnight for hybridization, washed first with 50% formamide in 2 × SSC (1 × SSC is 0.15 M NaCl and 0.017 M sodium citrate) solution at 50°C for 2 hr and then with H2O five times at room temperature, and digested with 20 μg/mL RNase A in H2O for 20 min at 37°C. The sections on the slides were washed completely with PBS, buffer 1 (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 0.15 M NaCl solution), and buffer 2 (0.5% blocking reagent [Boehringer Mannheim] in buffer 1); prehybridized with buffer 3 (1% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100 in buffer 1); and hybridized with anti–digoxigenin–alkaline phosphatase, 1:3000 in buffer 1, for 1 hr. The slides were washed with H2O five times, buffer 1 for 5 min, and buffer 4 (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.05 M MgCl2) for 5 min. Later, they were incubated with 0.15 mg/mL nitroblue tetrazolium salt and 0.75 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate in buffer 4 for 6 to 8 hr, after which the sections were observed under the microscope.

Total RNA Extraction and RNA Gel Blot Analysis

One gram of the tissues in the area of the apex, including the second node, the inoculated leaves and stems in the area of the nodes, and the cotyledons and the stems to which the cotyledons were attached, were harvested from mock-, Fny-CMV–, and Fny-CMV– plus D4-satRNA–inoculated tomato at 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 days postinoculation (DPI). The tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen and mixed with 2 mL of extraction buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 0.01 M Tris, pH 8, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 1% SDS). The mixture was extracted with phenol:chloroform (1:1 [v/v]) twice and precipitated with 0.3 M sodium acetate and ethanol. The nucleic acids were resuspended in Tris-EDTA buffer (Sambrook et al., 1989) and digested with RNase-free DNase (RQ1; Promega) and then reextracted with phenol:chloroform and reprecipitated with ethanol. The final RNA pellets were resuspended in 150 μL of H2O. Five microliters of each denatured sample (or of a 1:10 dilution for the 11-DPI sample) was added to 15 μL of denaturing buffer (formamide:formaldehyde [37% solution]:10 × Mops buffer [Sambrook et al., 1989], 500:162:100 [v/v/v]), heated to 65°C for 10 min, and loaded onto a 1.5% agarose gel. After electrophoresis, the samples were bidirectionally transferred to two Hybond N+ (Amersham) membranes. The probes were α-P32-UTP–labeled minus- or plus-strand satRNAs generated by in vitro transcription as described above. After hybridization, band density was determined by using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Probes were stripped in boiling 0.1% SDS for 2 hr, and the blots were rehybridized with an 18S rRNA cDNA probe. The hybridization density was again measured using the PhosphorImager. The relative amounts of the plus and minus strands were measured as a ratio with the 18S rRNA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tom Wolpert for providing the DNA ladder from oat, Drs. Elison Blancaflor and NingHui Cheng for careful reading of the manuscript, and Cuc Ly for assistance with images. This work was supported by the S.R. Noble Foundation.

References

- Bendahmane, A., Kanyuka, K., and Baulcombe, D.C. (1999). The Rx gene from potato controls separate virus resistance and cell death responses. Plant Cell 11, 781–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, J.J., and García-Arenal, F. (1997). Analysis of the in vitro secondary structure of cucumber mosaic virus satellite RNA. RNA 3, 1052–1067. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestwick, C.S., Brown, I.R., Bennett, M.H.R., and Mansfield, J.W. (1997). Localization of hydrogen peroxide accumulation during the hypersensitive reaction of lettuce cells to Pseudomonas syringae pv phaseolicoli. Plant Cell 9, 209–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamnongpol, S., Willekens, H., Langebartels, C., Montagu, M.V., Inzé, D., and Camp, W.V. (1996). Transgenic tobacco with a reduced catalase activity develops necrotic lesions and induces pathogenesis-related expression under high light. Plant J. 10, 491–503. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., and Foolad, M.R. (1997). Molecular organization of a gene in barley which encodes a protein similar to aspartic protease and its specific expression in nucellar cells during degeneration. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 821–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen, E.S., Romero, J.M., Doyle, S., Elliott, R., Murphy, G., and Carpenter, R. (1990). floricaula: A homeotic gene required for flower development in Antirrhinum majus. Cell 63, 1311–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crescenzi, A., Barbarossa, L., Cillo, F., Di Franco, A., Vovlas, N., and Gallitelli, D. (1993). Role of cucumber mosaic virus and its satellite RNA in the etiology of tomato fruit necrosis in Italy. Arch. Virol. 131, 321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl, J.L., Dietrich, R.A., and Richberg, M.H. (1996). Death don't have no mercy: Cell death programs in plant–microbe interactions. Plant Cell 8, 1793–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danon, A., and Gallois, P. (1998). UV-C radiation induces apoptotic-like changes in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 437, 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo, O., and Lam, E. (1998). Caspases and programmed cell death in the hypersensitive response of plants to pathogens. Curr. Biol. 8, 1129–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan, R., Reynolds, A., Hancock, J.T., and Neill, S.J. (1998). Harpin and hydrogen peroxidase both initiate programmed cell death but have differential effects on defense gene expression in Arabidopsis suspension cultures. Biochem. J. 330, 115–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.S., Carter, S.A., and Nelson, R.S. (1996). Enhanced cytochemical detection of viral proteins and RNAs using double-sided labeling and light microscopy. BioTechniques 20, 111–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake, R., John, I., Farrell, A., Cooper, W., Schuch, W., and Grierson, D. (1996). Isolation and analysis of cDNAs encoding tomato cysteine proteases expressed during leaf senescence. Plant Mol. Biol. 30, 755–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R.E., Yuan, J., and Horvitz, H.R. (1991). Mechanisms and functions of cell death. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 7, 663–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, H. (1997). Tracheary element differentiation. Plant Cell 9, 1147–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M., and Showalter, A.M. (1999). Yariv reagent treatment induces programmed cell death in Arabidopsis cell cultures and implicates arabinogalactan protein involvement. Plant J. 19, 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Arenal, F., and Palukaitis, P. (1999). Structure and functional relationships of satellite RNAs of cucumber mosaic virus. In Satellites and Defective Viral RNAs, P.K. Vogt and A.O. Jackson, eds (Berlin: Springer-Verlag), pp. 37–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gavrieli, Y., Sherman, Y., and Ben-Sasson, S.A. (1992). Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J. Cell Biol. 119, 493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazener, J.A., Orlandi, E.W., and Baker, C.J. (1996). The active oxygen response of cell suspensions to incompatible bacteria is not sufficient to cause hypersensitive cell death. Plant Physiol. 110, 759–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graca, J.V., and Martin, M.M. (1976). An electron microscope study of hypersensitive tobacco infected with tobacco mosaic virus at 32°C. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 8, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.T. (1997). Programmed cell death in plant–pathogen interactions. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 525–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.T., Guo, A., Klessig, D.F., and Ausubel, F.M. (1994). Programmed cell death in plants: A pathogen-triggered response activated coordinately with multiple defense functions. Cell 77, 551–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groover, A., DeWitt, N., Heidel, A., and Jones, A. (1997). Programmed cell death of plant tracheary elements differentiating in vitro. Protoplasma 196, 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Jabs, T., Dietrich, R.A., and Danl, J.L. (1996). Initiation of runaway cell death in an Arabidopsis mutant by extracellular superoxide. Science 273, 1853–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.M., and Dangl, J.L. (1996). Logjam at the Styx: Programmed cell death in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jordá, C., Alfaro, A., Aranda, M.A., Moriones, E., and García-Arenal, F. (1992). Epidemic of cucumber mosaic virus plus satellite RNA in tomatoes in eastern Spain. Plant Dis. 76, 363–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kaper, J.M., and Waterworth, H.E. (1977). Cucumber mosaic virus–associated RNA 5: Causal agent for tomato necrosis. Science 196, 429–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper, J.M., Geletka, L.M., Wu, G.S., and Tousignant, M.E. (1995). Effect of temperature on cucumber mosaic virus satellite-induced lethal tomato necrosis is helper virus strain dependent. Arch. Virol. 140, 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, J.F.R., Wyllie, A.H., and Currie, A.R. (1972). Apoptosis: A basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer 26, 239–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosslak, R.M., Chamberlin, M.A., Palmer, R.G., and Bowen, B.A. (1997). Programmed cell death in the root cortex of soybean root necrosis mutants. Plant J. 11, 729–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurath, G., and Palukaitis, P. (1989). Satellite RNAs of cucumber mosaic virus: Recombinants constructed in vitro reveal independent functional domains for chlorosis and necrosis in tomato. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, C., and Dixon, R.A. (1997). The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 251–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May, M.J., Hammond-Kosack, K.E., and Jones, J.D.G. (1996). Involvement of reactive oxygen species, glutathione metabolism, and lipid peroxidation in the Cf-gene–dependent defense re-sponse of tomato cotyledons induced by race-specific elicitors of Cladosporium fulvum. Plant Physiol. 110, 1367–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler, R., and Lam, E. (1995). Identification, characterization, and purification of a tobacco endonuclease activity induced upon hypersensitive response cell death. Plant Cell 7, 1951–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler, R., and Lam, E. (1997). Characterization of nuclease activities and DNA fragmentation induced upon hypersensitive re-sponse cell death and mechanical stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 34, 209–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler, R., Shulaev, V., and Lam, E. (1995). Coordinated activation of programmed cell death and defense mechanisms in transgenic tobacco plants expressing a bacterial proton pump. Plant Cell 7, 29–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler, R., Shulaev, V., Seskar, M., and Lam, E. (1996). Inhibition of programmed cell death in tobacco plants during a pathogen-induced hypersensitive response at low oxygen pressure. Plant Cell 8, 1991–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler, R., Feng, X., and Cohen, M. (1998). Post-transcriptional suppression of cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase expression during pathogen-induced programmed cell death in tobacco. Plant Cell 10, 461–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarre, D.A., and Wolpert, T.J. (1999). Victorin induction of an apoptotic/senescence-like response in oats. Plant Cell 11, 237–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palukaitis, P., Roossinck, M.J., Dietzgen, R.G., and Francki, R.I.B. (1992). Cucumber mosaic virus. In Advances in Virus Research, K. Maramorosch, F.A. Murphy, and A.J. Shatkin, eds (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), pp. 281–348. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pastori, G.M., and del Río, L.A. (1997). Natural senescence of pea leaves. An activated oxygen-mediated function for peroxisomes. Plant Physiol. 113, 411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell, R.I., and Lamb, C. (1997). Programmed cell death in plants. Plant Cell 9, 1157–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Alvarado, G., and Roossinck, M.J. (1997). Structural analysis of a necrogenic strain of cucumber mosaic cucumovirus satellite RNA in planta. Virology 236, 155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roossinck, M.J., and White, P.S. (1998). Cucumovirus isolation and RNA extraction. In Plant Virology Protocols, G.D. Foster and S.C. Taylor, eds (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press), pp. 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Roossinck, M.J., Kaplan, I., and Palukaitis, P. (1997). Support of a cucumber mosaic virus satellite RNA maps to a single amino acid proximal to the helicase domain of the helper virus. J. Virol. 71, 608–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryerson, D.E., and Heath, M.C. (1996). Cleavage of nuclear DNA into oligonucleosomal fragments during cell death induced by fungal infection or by abiotic treatments. Plant Cell 8, 393–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E.F., and Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- Sleat, D.E., and Palukaitis, P. (1990). Site-directed mutagenesis of a plant viral satellite RNA changes its phenotype from ameliorative to necrogenic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 2946–2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleat, D.E., Zhang, L., and Palukaitis, P. (1994). Mapping determinants within cucumber mosaic virus and its satellite RNA for the induction of necrosis in tomato plants. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 7, 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, M., Belenghi, B., Delledonne, M., Menachem, E., and Levine, A. (1999). The involvement of cysteine proteases and protease inhibitor genes in the regulation of programmed cell death in plants. Plant Cell 11, 431–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, J.C., and Hansen, G. (1999). Mannose induces an endonuclease responsible for DNA laddering in plant cells. Plant Physiol. 121, 71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, H., Chen, Z., Du, H., Liu, Y., and Klessig, D.F. (1997). Development of necrosis and activation of disease resistance in transgenic tobacco plants with severely reduced catalase levels. Plant J. 11, 993–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taliansky, M.E., Ryabov, E.V., Robinson, D.J., and Palukaitis, P. (1998). Tomato cell death mediated by complementary plant viral satellite RNA sequences. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Vitha, S., Baluska, F., Mews, M., and Volkmann, D. (1997). Immunofluorescence detection of F-actin on low-melting-point wax sections from plant tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 45, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Jones, C., Ciacci-Zanella, J., Holt, T., Gilchrist, D.G., and Dickman, M.B. (1996. a). Fumonisins and Alternaria alternata lycopersici toxins: Sphinganine analog mycotoxins induce apoptosis in monkey kidney cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 3461–3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Li, J., Bostock, R.M., and Gilchrist, D.G. (1996. b). Apoptosis: A functional paradigm for programmed plant cell death induced by a host-selective phytotoxin and invoked during development. Plant Cell 8, 375–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen, C.-H., and Yang, C.-H. (1998). Evidence for programmed cell death during leaf senescence in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 39, 922–927. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, I.-C., Parker, J., and Bent, A.F. (1998). Gene-for-gene disease resistance without the hypersensitive response in Arabidopsis dnd1 mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7819–7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]