Abstract

Wnt signaling increases β-catenin abundance and transcription of Wnt-responsive genes. Our previous work suggested that the B56 regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) inhibits Wnt signaling. Okadaic acid (a phosphatase inhibitor) increases, while B56 expression reduces, β-catenin abundance; B56 also reduces transcription of Wnt-responsive genes. Okadaic acid is a tumor promoter, and the structural A subunit of PP2A is mutated in multiple cancers. Taken together, the evidence suggests that PP2A is a tumor suppressor. However, other studies suggest that PP2A activates Wnt signaling. We now show that the B56, A and catalytic C subunits of PP2A each have ventralizing activity in Xenopus embryos. B56 was epistatically positioned downstream of GSK3β and axin but upstream of β-catenin, and axin co-immunoprecipitated B56, A and C subunits, suggesting that PP2A:B56 is in the β-catenin degradation complex. PP2A appears to be essential for β-catenin degradation, since β-catenin degradation was reconstituted in phosphatase-depleted Xenopus egg extracts by PP2A, but not PP1. These results support the hypothesis that PP2A:B56 directly inhibits Wnt signaling and plays a role in development and carcinogenesis.

Keywords: B56/dephosphorylation/PP2A/Wnt/Xenopus

Introduction

The Wnt pathway is an evolutionarily conserved signaling mechanism whose deregulation results in defects in development and growth control. A crucial function of the Wnt pathway is to activate β-catenin-dependent transcription via a phosphorylation-regulated signal transduction pathway. Wnt is a secreted glycoprotein that binds to a member of the frizzled (fz) family of seven trans membrane receptors. Upon Wnt binding, dishevelled (dsh) becomes hyperphosphorylated and activated. Activated dsh leads to the inactivation of the Ser/Thr kinase glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β). When GSK3β is in its active state, β-catenin is phosphorylated on up to four N-terminal serine and threonine residues. This phosphorylation promotes an interaction between β-catenin and β-transducin repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP), which leads to the ubiquitylation and proteasome-mediated degradation of β-catenin. The dsh-induced inactivation of GSK3β leads to increased levels of β-catenin, which forms a complex with a member of the Lef/Tcf family of high mobility group (HMG)-like transcription factors and activates transcription. In mammalian cells, transcriptional targets include cell-cycle regulators, while dorsal-specific genes, such as siamois and Xnr-3, are activated in early Xenopus development (Barker et al., 2000; Peifer and Polakis, 2000; Seidensticker and Behrens, 2000).

Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and axin are negative regulators of the Wnt pathway. They anchor β-catenin and GSK3β in a multimeric β-catenin degradation complex that facilitates the phosphorylation of these components by GSK3β (Ikeda et al., 1998; Kishida et al., 1998; Sakanaka et al., 1998; Yamamoto et al., 1998). The phosphorylation of APC is essential for its interaction with β-catenin, while the presence of axin is required for the phosphorylation of β-catenin. Dsh inhibits the ability of GSK3β to phosphorylate β-catenin, APC and axin (Kishida et al., 1999; Yamamoto et al., 1999), and therefore leads to the propagation of the Wnt signal.

Mutations in components of the Wnt pathway have been identified in several tumor types, including colorectal cancers. Eighty-five percent of colorectal carcinomas have mutations in APC (Kinzler and Vogelstein, 1996). Of the 15% of colorectal carcinomas that do not have mutations in APC, ∼50% have mutations in β-catenin (Ilyas et al., 1997; Sparks et al., 1998). An analysis of colorectal carcinomas, therefore, suggests that deregulation of the Wnt pathway is essential for colorectal tumorigenesis.

Alterations in protein phosphorylation states are central to the regulation of Wnt signaling. Numerous components of the Wnt pathway, including dsh, axin, APC, GSK3β and β-catenin, are phosphoproteins. Multiple protein kinases have been shown to influence Wnt signaling, including GSK3β, protein kinase C (PKC), casein kinase I (CKI) and II (CKII) (Seidensticker and Behrens, 2000). Since the net phosphorylation state of a protein is determined by the relative activities of both kinases and phosphatases, it is likely that protein phosphatases also regulate Wnt signaling. We have found that protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) influences β-catenin signaling through its B56 regulatory subunit (Seeling et al., 1999). Okadaic acid (a phosphatase inhibitor) increases, while B56 expression reduces, β-catenin abundance in mammalian cells. B56 also reduces transcription of Wnt-responsive genes in both mammalian and Xenopus systems. In addition, the role of okadaic acid as a tumor promoter, and the identification of mutations in the structural A subunit of PP2A in multiple cancers, have led to the hypothesis that PP2A acts as a tumor suppressor. However, others have proposed that PP2A activates Wnt signaling. This hypothesis rests on the finding that the PP2A catalytic C subunit interacts with axin, dephosphorylates both axin and APC in vitro and cooperates with dsh in inducing secondary body axes in Xenopus embryos (Hsu et al., 1999; Willert et al., 1999; Ikeda et al., 2000; Ratcliffe et al., 2000).

PP2A is a heterotrimer, composed of a core AC heterodimer bound to a variable regulatory B subunit (Virshup, 2000; Janssens and Goris, 2001). There are three distinct families of PP2A B subunits currently known: B (PR55), B56 (PR61, B′) and B″ (PR72/130). B subunits confer substrate specificity and subcellular localization on the PP2A holoenzyme (McCright et al., 1996). We now demonstrate that PP2A A, B56α and C each possess ventralizing activity in Xenopus embryos in vivo, while PP2A activity is required for β-catenin degradation in vitro. B56 co-immunoprecipitates with axin, and it acts downstream of GSK3β and axin but upstream of β-catenin, suggesting that it is a component of the β-catenin degradation complex. These results suggest that a B56-containing PP2A heterotrimer directly inhibits Wnt signaling by dephosphorylating key regulatory protein(s) in the β-catenin degradation complex whose phosphorylation leads to pathway activation.

Results

B56 rescues secondary axis formation induced by Xwnt-8 in Xenopus embryos

β-catenin signaling is essential for the formation of the dorsoventral body axis in Xenopus. In early embryo development, β-catenin is enriched on the dorsal, relative to the ventral, side of the embryo. This enrichment leads to the formation of the Nieuwkoop center and subsequent dorsal structures (Moon and Kimelman, 1998). Positive regulators of the Wnt pathway, e.g. Wnt and β-catenin, have dorsalizing potential in the Xenopus embryo. Ventral microinjection of their RNA induces either the formation of a radially dorsalized embryo if the dorsalizing signal is large and/or equally distributed in the embryo, or a secondary body axis if the signal is small and/or localized. The dorsoanterior index (DAI) (Scharf and Gerhart, 1983; Kao and Elinson, 1988), as well as the degree of completeness of the secondary axis, can be used to classify the phenotypes of dorsoventrally altered embryos.

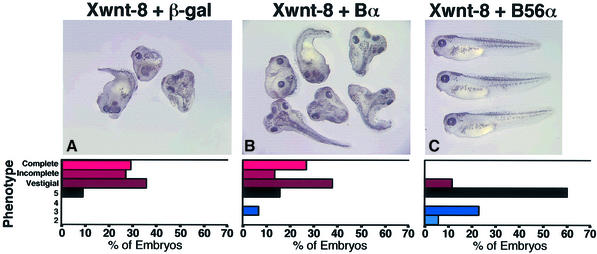

The ability of Xwnt-8 to induce siamois and Xnr-3 transcription in Xenopus animal cap explants is reduced by expression of the B56α subunit of PP2A (Seeling et al., 1999). To investigate the phenotypic consequences of B56 expression in the Xenopus embryo, we examined whether B56 was able to rescue the phenotype resulting from ectopic Xwnt-8 expression. The microinjection of Xwnt-8 RNA in the ventral side of an early Xenopus embryo efficiently induces the formation of a secondary body axis. If RNA of a negative regulator of Wnt signaling is injected with Xwnt-8 RNA, the formation of an ectopic axis can be reduced. Since the amount of Xwnt-8 co-injected with a putative ventralizing RNA can be titered to a minimum amount necessary to form a secondary body axis, this assay has a high sensitivity. When β-galactosidase (β-gal) RNA was injected along with Xwnt-8 RNA, 91% of the embryos exhibited a secondary body axis (Figure 1A). The Bα regulatory subunit of PP2A (a member of the B family) does not appear to inhibit Wnt-induced secondary axes, since 78% of the Xwnt-8/Bα RNA injected embryos exhibited a secondary axis (Figure 1B). However, when an equivalent amount of B56α RNA was co-injected with Xwnt-8 RNA, only 11% of the embryos had a secondary axis, all of which were vestigial (Figure 1C). B56α was highly effective at blocking the formation of a secondary axis and even promoted ventralization. Indeed, when the distribution of the embryo phenotypes was examined, a similar degree of secondary axis formation was exhibited with Xwnt-8/β-gal and Xwnt-8/Bα injections, but the majority of the Xwnt-8/B56α injected embryos were either wild type or ventralized. These results show that B56 has the ability to block the formation of an ectopic body axis through the inhibition of Wnt signaling.

Fig. 1. B56α expression rescues secondary axis formation induced by Xwnt-8 in Xenopus. Xenopus embryos were ventrally injected with Xwnt-8 and (A) β-gal, (B) Bα or (C) B56α RNA. Each photograph is shown with a diagram depicting the degree of axis formation. In these diagrams, the percentage of wild-type embryos are depicted with a black bar; embryos with a secondary axis or dorsalization are depicted in progressively lighter red bars as the phenotype becomes stronger and ventralized embryos are depicted in blue bars, which are progressively lighter with more highly ventralized embryos. The data shown are from a representative experiment, which was performed three times for a total n of 145 (β-gal), 149 (Bα) and 131 (B56α). The statistical analysis was carried out on the cumulative experiments, and the difference between the phenotypes resulting from the B56α and β-gal RNA microinjections is highly significant (p value <10–4), as is the difference between embryos injected with Bα and B56α RNA (p value <10–4).

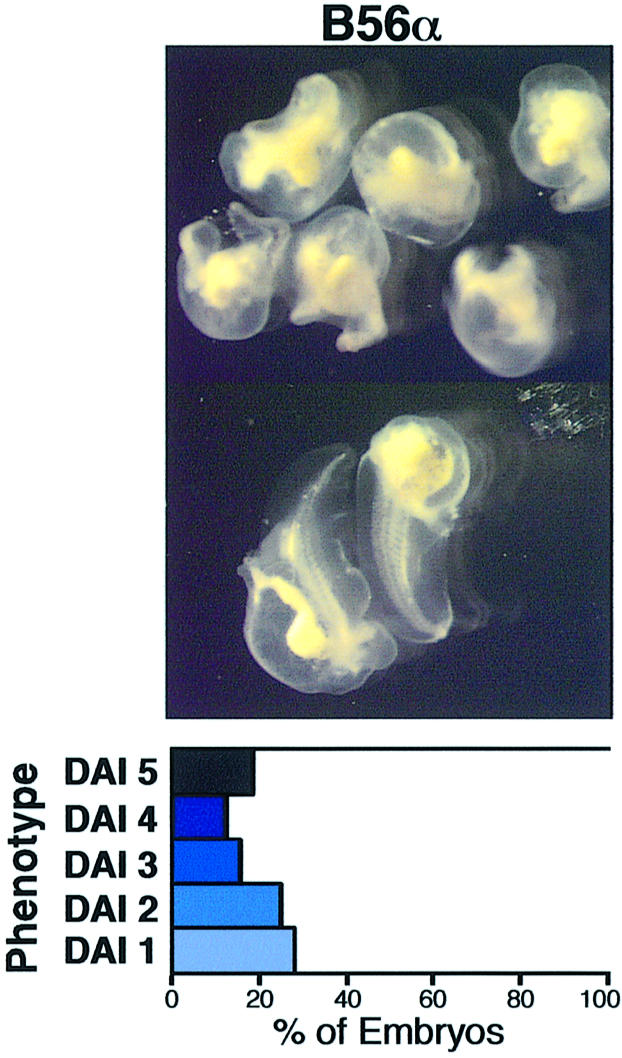

B56 ventralizes Xenopus embryos

The dorsal microinjection of RNA encoding negative regulators of the Wnt pathway, e.g. axin, can inhibit the formation of the primary body axis. However, it is more difficult to inhibit the formation of the primary body axis than an ectopic axis, since there is a high level of endogenous dorsalizing activity. To determine whether B56 is capable of blocking the formation of the endogenous body axis, we microinjected B56α RNA into the dorsal side of Xenopus embryos (Figure 2). We found that B56α RNA microinjection ventralized 81% of the embryos, while the microinjection of β-gal or Bα RNA did not ventralize any of the embryos (data not shown). The distribution of the embryo phenotypes shows that B56α induced a broad range of highly ventralized embryos, with DAIs from 1 to 4. Therefore, the ventralizing potential of B56α is sufficient to block the formation of the primary body axis by inhibiting endogenous dorsal signaling.

Fig. 2. B56α expression ventralizes Xenopus embryos. Xenopus embryos were dorsally injected with B56α RNA. The photographs are shown with a diagram depicting the degree of ventralization, as described in Figure 1. The data shown are from a representative experiment, which was performed two times for a total n of 90 (B56α). The statistical analysis was carried out on the cumulative experiments and the difference between the phenotypes resulting from the β-gal and B56α RNA microinjections is highly significant (p value <10–4).

PP2A A and C rescue secondary axis formation induced by Xwnt-8

Since B56α blocks secondary axis formation induced by ectopic Wnt expression, we wished to determine whether the A or C subunits of PP2A also block ectopic Wnt signaling. If B56 acts by increasing B56-specific PP2A activity in the Xenopus embryo, increased PP2A activity resulting from the microinjection of either A or C subunit RNA may also inhibit Wnt-induced secondary axis formation.

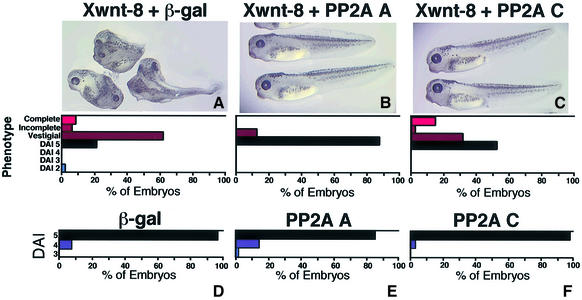

The ventral side of Xenopus embryos was microinjected with either PP2A A or C subunit RNA, along with Xwnt-8 RNA. Both the A and C subunits rescued Xwnt-8-induced secondary axis formation (Figure 3A–C). The A subunit was more effective than the C subunit, as it reduced the percentage of dorsalized embryos from 77 to 12%, while the C subunit reduced it to 48%. The distribution of the phenotypes reveals that the majority of the Xwnt-8/A subunit injected embryos were wild type, while approximately half of the Xwnt-8/C subunit and one-fourth of the Xwnt-8/β-gal injected embryos were wild type. The effect of the C subunit was weaker than that of the A subunit, in that it was able to rescue slightly dorsalized embryos, but had little effect on strongly dorsalized embryos. In summary, PP2A A and C subunits each rescue Wnt-induced secondary axis formation in the Xenopus embryo. This suggests that increasing PP2A activity by expression of the PP2A B56α, A or C subunit is sufficient to inhibit ectopic Wnt signaling and positions PP2A A and C downstream of Wnt.

Fig. 3. PP2A A and C rescue secondary axis formation induced by Xwnt-8, and PP2A A ventralizes Xenopus embryos. Xenopus embryos were ventrally injected with Xwnt-8 and (A) β-gal, (B) PP2A A, (C) PP2A C RNA or dorsally injected with (D) β-gal, (E) PP2A A or (F) PP2A C RNA. The photographs are shown with a diagram depicting the degree of axis formation, as described in Figure 1. The Xwnt-8 injection data are from a representative experiment, which was performed twice for a total n of 91 (β-gal), 91 (PP2A A) and 89 (PP2A C), while the ventralization experiment was performed twice with n of 122 (β-gal), 121 (PP2A A) and 124 (PP2A C). The statistical analysis was carried out on the cumulative experiments and the difference between the phenotypes in the Xwnt-8 rescue experiment resulting from β-gal and PP2A A RNA microinjections is highly significant (p value <10–4), while the difference for PP2A C is significant (p value = 0.023). For the ventralization experiment the difference between the phenotypes resulting from PP2A A and β-gal RNA microinjections is significant (p value = 0.023).

PP2A A ventralizes Xenopus embryos

To determine whether the ventralizing activity of the A and C subunits is potent enough to disrupt the formation of the primary body axis, Xenopus embryos were dorsally microinjected with β-gal, A subunit or C subunit RNA. The A subunit ventralized 16% of microinjected embryos, whereas β-gal and the C subunit injected embryos each displayed a low level of background ventralization (Figure 3D–F). Therefore, PP2A A, but not PP2A C, reduces the formation of the primary body axis, albeit weakly.

Epistasis analyses place B56 downstream of GSK3β and axin but upstream of β-catenin

Our earlier report showed that B56 acts upstream of β-catenin and APC in mammalian cells, since B56 was unable to reduce either β-catenin abundance or Lef-responsive reporter activity in cell lines possessing mutant APC or β-catenin (Seeling et al., 1999). We positioned the ventralizing activity of B56 within the Wnt pathway in the Xenopus embryo using molecular epistasis analyses. Lithium, an inhibitor of GSK3β and therefore an activator of Wnt signaling, dorsalizes Xenopus embryos (Kao et al., 1986). To order B56 with respect to GSK3β, we microinjected embryos dorsally with B56α or β-gal RNA, and then treated the embryos with lithium. Lithium treatment resulted in dorsalization of all of the embryos, 94% of which exhibited a DAI of 8. The microinjection of B56α RNA blocked lithium-induced dorsalization, reducing the percentage of dorsalized embryos to 38%, only 2% of which had a DAI of 8 (Figure 4A and B). The microinjection of a dominant-negative form of axin lacking the regulation of G-protein signaling domain, axinΔRGS, into the ventral side of a Xenopus embryo causes the formation of a secondary body axis. To position B56 with respect to axin, we ventrally microinjected embryos with axinΔRGS and either B56α or β-gal RNA. The microinjection of axinΔRGS resulted in complete secondary axis formation in 50% of embryos, with an additional 38% exhibiting an incomplete secondary axis. B56α decreased the extent of axinΔRGS-induced secondary axis formation, reducing the percentage of embryos with a complete secondary axis to 10%, with a concomitant increase in the embryos with an incomplete axis to 69% (Figure 4C and D). Therefore, B56 acts downstream of both GSK3β and axin in the early Xenopus embryo.

Fig. 4. Epistasis analyses place B56 downstream of GSK3β and axin but upstream of β-catenin. Xenopus embryos were dorsally microinjected with either β-gal or B56α RNA, as well as treated with lithium (A and B); or ventrally microinjected with either β-gal or B56α RNA and axinΔRGS RNA (C and D); wild-type (E and F) or mutant (G and H) β-catenin RNA; BVg1 RNA (I and J); or noggin RNA (K and L). Each photograph is shown with a diagram depicting the distribution of the embryo phenotypes, as described in Figure 1. The data shown are from a representative experiment, which was performed: three times for a total n of 94 or 92 (lithium), three times for a total n of 148 or 144 (axinΔRGS), twice for a total n of 93 or 95 (wild-type β-catenin) and 91 or 93 (mutβ-catenin), three times for a total n of 133 or 116 (BVg1), and four times for a total n of 196 or 187 (noggin), for β-gal or B56α, respectively. The statistical analysis was carried out on the cumulative experiments and the difference between the phenotypes resulting from the β-gal and B56α RNA microinjections is highly significant for lithium, axinΔRGS and wild-type β-catenin (each p value <10–4), while it is not significant for mutβ-catenin (p value = 0.460), BVg1 (p value = 0.335) or noggin (p value = 0.300).

The mutation or removal of the four putative GSK3β phosphorylation sites on β-catenin prevents its proteasome-mediated degradation. β-catenin RNA lacking these phosphorylation sites, therefore, induces a secondary axis more efficiently than wild-type β-catenin RNA. To position B56 with respect to β-catenin, we examined the ability of B56 to rescue the phenotype caused by the ventral microinjection of either wild-type β-catenin, or a mutant β-catenin with these phosphorylation sites mutated to alanine (mutβ-catenin). Wild-type β-catenin induced a secondary axis in 79% of the embryos. B56α blocked secondary axis formation induced by wild-type β-catenin, reducing the percentage of embryos with a secondary axis to 4% (Figure 4E and F). However, B56α did not affect the level of secondary axis formation induced by mutβ-catenin (Figure 4G and H), which remained at 96–100% in the presence or absence of B56α. This is consistent with our earlier results in mammalian tissue culture cells, which showed that B56 was able to reduce levels of cotransfected wild-type β-catenin, but not those of a mutant β-catenin lacking its N-terminal 90 amino acids (Seeling et al., 1999). Our data suggest that B56 reduces β-catenin abundance by activating the β-catenin destruction complex, perhaps by dephosphorylating and activating GSK3β, leading to the phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin. Since mutβ-catenin cannot be phosphorylated and degraded, we would expect that B56 could alter the abundance of wild-type but not mutant β-catenin. Consequently, the data are consistent with B56 acting upstream of β-catenin.

The ventralizing activity of B56 is specific for the Wnt pathway

The dorsoventral axis of the Xenopus embryo is specified by the sperm entry point. A series of events follows this specification, including the enrichment of β-catenin on the dorsal side of the embryo, which leads to the formation of the Nieuwkoop center and subsequently the Spemann organizer. Vg1 and noggin dorsalize Xenopus embryos acting downstream of, or parallel to, the Nieuwkoop center and the Wnt signaling pathway but upstream of the Spemann organizer (Fagotto et al., 1997). We used epistasis analyses to determine whether the ability of B56 to inhibit the formation of dorsal structures is specific to the Wnt pathway, or whether B56 has a more general anti-dorsalizing activity. We ventrally microinjected embryos with either bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2)-Vg1 (BVg1) or noggin RNA, along with either B56α or β-gal RNA. BVg1 microinjection resulted in the formation of vestigial secondary axes in ∼45% of the embryos, either in the presence or absence of B56α (Figure 4I and J). Noggin induced dorsalization in ∼97% of the embryos, the majority exhibiting DAIs of 7 and 8, and this dorsalization was not affected by the presence of B56α (Figure 4K and L). Therefore, B56 acts upstream of these two factors, apparently due to its ability to reduce Wnt signaling.

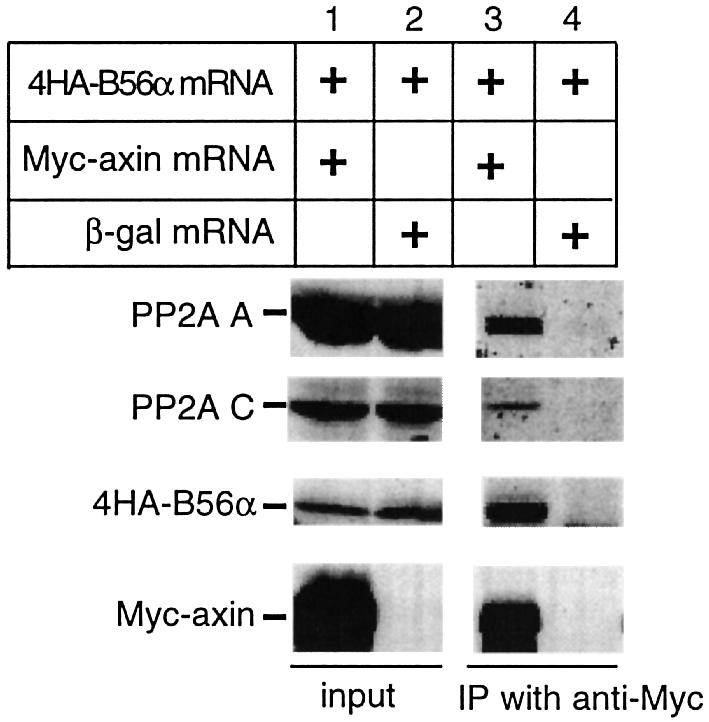

PP2A A, C and B56α co-immunoprecipitate with axin

APC and axin anchor β-catenin and GSK3β in a multimeric β-catenin degradation complex. Since epistasis analyses place B56 downstream of GSK3β and axin but upstream of β-catenin and APC, it is reasonable to expect that B56 may also be present in the β-catenin degradation complex. In addition, PP2A A and C have been shown to co-immunoprecipitate with axin (Hsu et al., 1999) (Z.-H.Gao, J.M.Seeling, D.M.Virshup, in preparation). To determine whether a PP2A holoenzyme containing B56 is associated with the β-catenin degradation complex, co-immunoprecipitation experiments were carried out. Hemagglutinin (HA)-B56α and Myc-axin were coexpressed in Xenopus egg extracts, followed by an anti-Myc immunoprecipitation, SDS–PAGE and western blotting. As shown in Figure 5, PP2A A, C and B56α co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-axin. These results suggest that a PP2A holoenzyme containing B56 is present in the β-catenin degradation complex.

Fig. 5. Co-immunoprecipitation of PP2A A, C and B56 with axin. The indicated RNAs were translated in Xenopus egg extracts, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc antibodies. Lanes 1 and 2 contain extract expressing the indicated RNAs, while lanes 3 and 4 contain the corresponding Myc-immunoprecipitates. Immunoblotting was performed with anti-human PP2A A, anti-human PP2A C, anti-HA or anti-Myc antibodies. PP2A A, C and B56α co-immunoprecipitate in the presence, but not absence, of axin (compare lanes 3 and 4). The data shown are representative of experiments repeated three times with similar results.

Expression of B56α, but not Bα or small t antigen, accelerates β-catenin degradation in Xenopus egg extracts

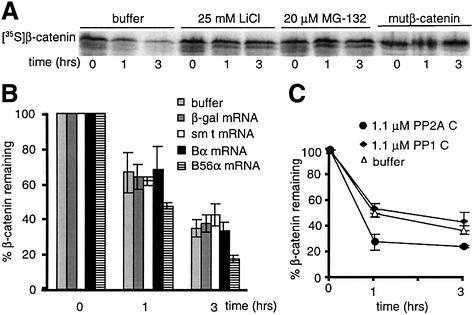

Salic et al. (2000) introduced an in vitro system that recapitulates functional data on numerous Wnt pathway components initially characterized in other systems. We utilized this system to further characterize the role of PP2A in β-catenin degradation. [35S]β-catenin was degraded in Xenopus egg extracts with a half-life of ∼1 h (Figure 6A). Consistent with the results of Salic et al. (2000) inclusion of lithium or the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 inhibited β-catenin degradation. Furthermore, mutβ-catenin was resistant to degradation (Figure 6A). These results verify that our procedure also recapitulates the essential features of Wnt signaling (Salic et al., 2000).

Fig. 6. PP2A B56α and C, but not Bα or sm t, accelerate β-catenin degradation in Xenopus egg extracts. (A) [35S]β-catenin or mutβ-catenin was incubated with extracts in the presence of buffer, 25 mM LiCl or 20 µM MG-132. (B) The indicated RNA was translated in extracts prior to the degradation assay. Data shown are the mean of two experiments, each performed in triplicate, ± SD. (C) Purified PP2A C or PP1 C was incubated in extracts prior to the degradation assay. Data shown are the mean of two experiments, each performed in duplicate, ± SD.

Prior studies in mammalian systems suggest that B56 expression accelerates β-catenin proteolysis (Seeling et al., 1999). To determine whether B56 alters β-catenin stability in Xenopus egg extracts, we tested the effects of B56α expression on β-catenin degradation. Two additional proteins that modulate PP2A activity, Bα and SV40 small t antigen (sm t) were tested as well. sm t can displace Bα, but not B56, from a PP2A heterotrimer (Pallas et al., 1990; Yang et al., 1991), and therefore would only affect degradation if Bα was involved. If B56 is acting by displacing Bα from PP2A, B56 and sm t would be expected to affect β-catenin degradation in a similar manner. The expression of B56α significantly accelerated β-catenin degradation. However, sm t and Bα expression had no effect on β-catenin proteolysis (Figure 6B), suggesting that a Bα-containing PP2A does not regulate β-catenin degradation. Furthermore, the addition of purified recombinant sm t to 6 µM produced similar results (data not shown). The data are consistent with our earlier results, which also suggest that B56, but not Bα, downregulates β-catenin (Seeling et al., 1999).

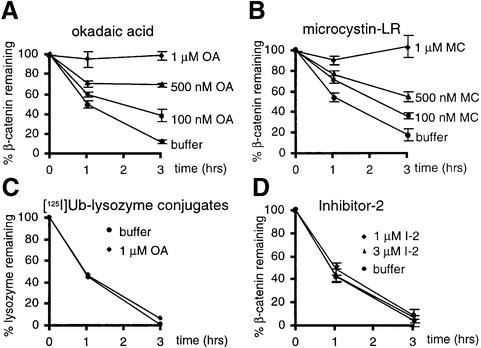

Inhibition of β-catenin degradation by okadaic acid and microcystin-LR, but not PP1 inhibitor-2

The data suggest that PP2A:B56 is present in the β-catenin degradation complex and inhibits Wnt signaling by promoting β-catenin degradation. To test whether PP2A is required for β-catenin degradation, loss-of-function experiments were performed. Ser/Thr phosphatase inhibitors with differential specificity were employed to determine whether blocking the activity of specific phosphatases affects β-catenin degradation in Xenopus egg extracts. Okadaic acid and microcystin-LR inhibit two major cellular Ser/Thr protein phosphatases, PP2A and PP1, plus several less abundant phosphatases (Brewis et al., 1993; Chen et al., 1994). Okadaic acid and microcystin-LR reduced β-catenin degradation when added to extracts at concentrations as low as 100 nM, and completely blocked it at 1 µM (Figure 7A and B). Okadaic acid and microcystin-LR are not general inhibitors of proteasomal degradation, since neither blocked the degradation of ubiquitylated lysozyme (Figure 7C and data not shown). These results are consistent with a PP1-PP2A type Ser/Thr phosphatase being required for β-catenin degradation. Of note, the concentrations of okadaic acid or microcystin-LR required in this assay are much higher than the reported IC50 using purified protein phosphatases (for okadaic acid, IC50 = 1–5 nM for PP2A and IC50 = 10–100 nM for PP1). This is presumably due to the high concentration of protein phosphatases in egg extracts. Indeed, consistent with other reports (Hendrix et al., 1993; Bosch et al., 1995; Lin et al., 1998), we found that the PP2A C subunit concentration in egg extracts was ∼3 µM (data not shown).

Fig. 7. Ser/Thr phosphatase inhibitors block β-catenin degradation. β-catenin degradation is inhibited in the presence of the indicated concentrations of (A) okadaic acid (OA) or (B) microcystin-LR (MC). (C) OA does not affect [125I]ubiquitylated lysozyme degradation. (D) I-2 at 1 and 3 µM has no effect on β-catenin degradation. Data shown are the mean of three experiments, each performed in triplicate, ± SD, except for [125I]ubiquitylated lysozyme, which was performed once in duplicate.

An inhibitor of PP1 that does not affect the activity of PP2A, PP1 inhibitor-2 (I-2), allowed us to determine whether PP1 activity was required for β-catenin degradation. I-2 had no effect on the rate of β-catenin degradation (Figure 7D), suggesting that PP1 activity is not required for β-catenin degradation. The inhibitory activity of I-2 was verified by its ability to inhibit PP1 activity towards phosphorylase a (data not shown). These results suggest that PP2A or one of the less abundant Ser/Thr phosphatases, but not PP1, is involved in β-catenin degradation.

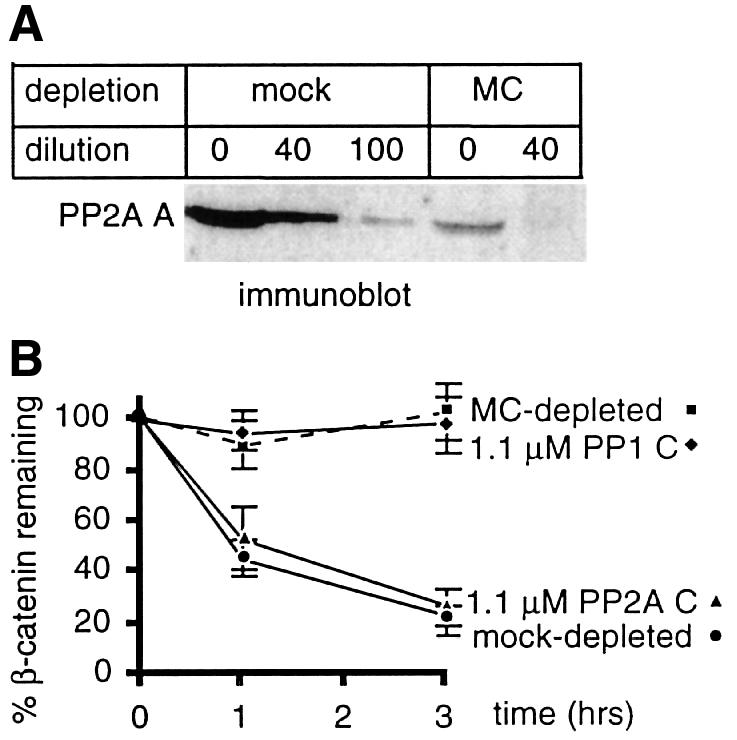

PP2A activity is required for β-catenin degradation

The inhibition of β-catenin degradation by okadaic acid and microcystin-LR, but not I-2, suggests that a non-PP1 phosphatase promotes β-catenin degradation. To determine whether PP2A can carry out this function, egg extracts were supplemented with either purified PP2A C or PP1 C. PP2A C, but not PP1, accelerated β-catenin degradation (Figure 6C). To further characterize the role of PP2A in β-catenin degradation, we used microcystin-LR-coupled Sepharose beads to deplete Ser/Thr protein phosphatases from egg extracts. Microcystin-LR binds to PP2A and PP1 with high affinity, and has been used to affinity purify PP2A and PP1 (Campos et al., 1996). After one round of incubation with microcystin-LR–Sepharose, ∼75% of PP2A was depleted from egg extracts (Figure 8A). As shown in Figure 8B, microcystin-LR–Sepharose depletion of extracts abrogated β-catenin degradation. Microcystin-LR depletion does not generally inhibit proteasome-mediated degradation, since it does not reduce, but rather accelerates, the degradation of IκB (data not shown). The addition of purified PP2A C, but not the equivalent amount of PP1 C, to microcystin-LR-depleted extracts fully reconstituted β-catenin degradation. This result suggests that PP2A is the only rate-limiting microcystin-sensitive phosphatase required for β-catenin degradation. The finding that near physiological amounts of purified PP2A reconstituted β-catenin degradation to a rate indistinguishable from the endogenous rate is consistent with PP2A being the sole Ser/Thr phosphatase that is required for β-catenin degradation.

Fig. 8. PP2A activity is required for β-catenin degradation. (A) Ser/Thr phosphatases were removed from egg extracts by MC–Sepharose. To determine how much PP2A was removed, serial dilutions of mock-depleted or MC-depleted extracts were immunoblotted with anti-PP2A A antibody. (B) β-catenin degradation was assessed using mock- or MC-depleted extracts, with or without supplementation of the MC-depleted extracts with purified PP2A or PP1 C subunit. Data shown are the mean of three experiments, each performed in triplicate, ± SD.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates an essential role for PP2A in Wnt signaling. PP2A B56α, A and C subunits each have ventralizing activity in Xenopus embryos. The positioning of B56 downstream of GSK3β and axin but upstream of β-catenin, and the co-immunoprecipitation of B56, A and C subunits with axin, suggest that PP2A is a component of the β-catenin degradation complex. B56α expression accelerated, while the addition of phosphatase inhibitors blocked, β-catenin degradation in Xenopus egg extracts. The effects of B56 were specific, since a member of the B subunit family, Bα, did not appreciably affect either axis formation or β-catenin degradation. Also, sm t, which displaces Bα but not B56 from PP2A, had no effect on β-catenin degradation. We further demonstrated that PP2A activity is required for β-catenin degradation in extracts. These results suggest that the effects of B56 are caused by an increase in B56-dependent PP2A activity, and not by a reduction in non-B56-dependent PP2A activity. They also provide further evidence that PP2A:B56 directly inhibits Wnt signaling.

Inhibition of PP2A activity contributes to cell proliferation and aberrant development. Alterations in PP2A C expression levels affect development in multiple organisms (Shiomi et al., 1994; Wassarman et al., 1996; Gotz et al., 1998). Okadaic acid causes cancer of the skin and gastrointestinal tract in rodents (Suganuma et al., 1992). Mutations of PP2A A predicted to alter B and/or C subunit binding have been identified in colon, breast, lung and melanoma cancers (Wang et al., 1998; Calin et al., 2000; Takagi et al., 2000). Importantly, two of these A subunit mutant proteins have been shown to be defective exclusively in B56 binding, with normal binding to B, B″ and C subunits (Ruediger et al., 2001). This finding suggests that defective B56 subunit binding is essential for the oncogenic properties of these cancer-associated mutant A subunits. The data suggest that perturbations of PP2A function, notably B56-specific PP2A function, can lead to defects in growth and development.

PP2A is positioned to play an important role in early Xenopus development. B56, A and C subunits are expressed in the early embryo. Northern blotting reveals that PP2A Aβ and Cα are expressed throughout early development (Bosch et al., 1995; Paillard et al., 2000), and B56 has been identified in cDNA libraries made from early stage embryos. The presence of PP2A may negatively regulate Wnt signaling on the ventral side of the embryo, preventing inappropriate Wnt signaling activity. It will be interesting to determine whether PP2A expression or activity is absent or low on the dorsal, but high on the ventral, side of the embryo.

Our molecular epistasis and co-immunoprecipitation analyses place B56 in the β-catenin degradation complex. Besides the core components of GSK3β, axin, β-catenin and APC, this complex has also been found to contain dsh. Given the inhibitory effects of B56 on Wnt signaling, the most obvious candidates for PP2A:B56 substrates are components of this complex whose phosphorylation leads to the activation of the pathway, e.g. dsh and GSK3β. Dsh and B56ε [a B56 family member that also reduces β-catenin abundance in mammalian cells (Seeling et al., 1999)] have been found to interact by two-hybrid analyses (Ratcliffe et al., 2000). Wnt signaling leads to dsh hyperphosphorylation, and PP2A:B56 may reduce Wnt signaling by dephosphorylating and inactivating dsh. PP2A:B56 could also dephosphorylate and activate GSK3β. It was demonstrated as early as 1993 that PP2A dephosphorylates GSK3β in vitro (Sutherland et al., 1993; Welsh and Proud, 1993). GSK3β is inactivated by phosphorylation in other signal transduction pathways, such as insulin and epidermal growth factor. However, it is known that the target residue for phosphorylation and inhibition in insulin signaling, Ser9, is not involved in the regulation of Wnt signaling (Ding et al., 2000). Additional Wnt pathway components and/or new sites of phosphorylation on known proteins are likely to be identified whose phosphorylation increases Wnt signaling. These proteins/sites are also potential PP2A:B56 targets.

B56 was more effective than the A and C subunits in reducing both primary and Xwnt-8-induced secondary axes in the Xenopus embryo. This could be due to multiple factors. B56, in its role as a PP2A targeting subunit, may direct the PP2A holoenzyme to components of the β-catenin destruction complex. The strong ventralizing activity of B56 in the embryo suggests that B56 may be the limiting component of the PP2A heterotrimer in the early Xenopus embryo. Exogenous B56 may bind the majority of the endogenous A and C subunits, yielding increased B56-targeted PP2A activity. There may not be sufficient levels of endogenous B56 present, however, to bind all of the protein expressed from microinjected A or C subunit RNA, resulting in a less potent response. The weaker ventralizing activity of PP2A C may also reflect its tight transcriptional/translational regulation. In mammalian cells, it has been observed that endogenous C subunit levels go down to compensate for increased levels of exogenous C subunit (Baharians and Schonthal, 1998). The weak ventralizing activity of PP2A C in the Xenopus embryo may be due to such downregulation. Alternatively, variation in the stability of the individual RNAs and/or proteins may contribute to the attenuated efficacy of PP2A A and C.

Alternative roles for PP2A in the Wnt pathway have been proposed. We have shown that okadaic acid increases the abundance of β-catenin in mammalian cells, and that it does so at concentrations that promote PP2A-specific inhibition (Seeling et al., 1999). Overexpression of the B56 subunit in mammalian cells, which leads to increased B56-specific PP2A activity (J.M.Seeling, unpublished observations), reduces both β-catenin abundance and transcription of Wnt-responsive genes (Seeling et al., 1999). In addition, the tumor promoter activity of okadaic acid and the identification of A subunit mutations in multiple cancers support the hypothesis that PP2A acts as a tumor suppressor. However, it has been suggested that PP2A may activate, rather than inhibit, Wnt signaling. The report of a direct interaction between PP2A C and axin, and phenotypes resulting from various axin mutations in mice, led Hsu et al. (1999) to suggest that PP2A dephosphorylates β-catenin, thereby activating Wnt signaling (Hsu et al., 1999; Ikeda et al., 2000). The PP2A AC heterodimer dephosphorylates APC and axin in vitro, and these findings also led to the suggestion that PP2A could activate Wnt signaling (Willert et al., 1999; Ikeda et al., 2000). The activity of the AC heterodimer in vitro, however, may not reflect the specific activity of a heterotrimer in vivo, since the association of a B subunit with the AC heterodimer targets the enzyme to specific locations in the cell and reduces the non-specific activity of the phosphatase (Cegielska et al., 1994; McCright et al., 1996; Price and Mumby, 2000). None of these reports provided in vivo evidence that PP2A activates Wnt signaling.

Recently, it was found that the C subunit could cooperate with dsh in inducing a secondary body axis in Xenopus, although the C subunit alone did not induce a secondary axis (Ratcliffe et al., 2000). The C subunit appeared to act downstream of or parallel to β-catenin, since it did not affect β-catenin abundance. Since free C subunit does not exist in cells, it may be acting via an AC heterodimer, or an ABC heterotrimer. The ability of PP2A to cooperate with dsh suggests that in this case, the PP2A substrate inhibits Wnt signaling when it is phosphorylated, and that its dephosphorylation by PP2A activates signaling. Additional data suggest that a B (rather than a B56)-containing PP2A heterotrimer is a positive regulator of Wnt signaling. Expression of sm t, which displaces B but not B56 from the PP2A heterotrimer, reduces expression of a Wnt-responsive reporter (Ratcliffe et al., 2000). Our finding that Bα and sm t do not affect β-catenin abundance is consistent with the conclusion that PP2A:Bα acts downstream of β-catenin.

The apparently contradictory roles of PP2A in the Wnt pathway can be reconciled if distinct PP2A heterotrimers act on different substrates, or at multiple sites within a given substrate, with opposing consequences. Wnt signaling is regulated by phosphorylation at multiple points. At least four kinases, GSK3β, PKC, CKI and CKII, have been shown to affect Wnt signaling. Each phosphorylation step carried out by a kinase is likely to have a counter-regulatory dephosphorylation step carried out by a phosphatase, consequently, there are likely to be as many phosphatases acting in the Wnt pathway as kinases. In contrast to the plethora of kinases, there are only a limited number of Ser/Thr phosphatase catalytic subunits. Diversity of phosphatase function is achieved through variation in the bound regulatory subunit. Since PP2A is one of the most abundant cellular phosphatases, it is reasonable to expect that PP2A has multiple roles in the pathway. The only other Ser/Thr protein phosphatase reported to be in the Wnt pathway is PP2C, which has been shown to activate Lef-1-dependent transcription and dephosphorylate axin in vitro (Strovel et al., 2000). Yet, the ventralizing activity of PP2A subunits in Xenopus embryos, and its requirement for β-catenin degradation, along with the roles of okadaic acid and the A subunit in cancer, cumulatively suggest that the dominant role of PP2A in Wnt signaling is inhibitory.

Materials and methods

Genes

The following cDNAs were used: human B56α (L42373), rat Bα (M83298), human PP2A Aα (NM014225), human PP2A Cα (M36951), sm t (NC0016691358), human β-catenin (X87838) and Xenopus Xwnt-8 (X57234).

RNA microinjections

RNA was prepared using mMessage mMachine (Ambion) and purified using RNeasy (Qiagen). Embryos were microinjected at the 4–8 cell stage and scored after 3 days at room temperature. The ventral versus dorsal cells of the embryos were distinguished by pigmentation. The ventral microinjections were done at the equatorial midline in one ventral cell, while the dorsal microinjections were performed in both dorsal cells at the equatorial midline. The following amounts of RNA were microinjected: Xwnt-8, 5 pg; B56α, 1.5–2 ng for ventralization and Wnt rescue experiments, 100–400 pg for epistasis experiments; Bα, 1.5–2 ng; PP2A A or C, 3 ng; axinΔRGS, 1.2–1.75 ng; wild-type β-catenin or mutβ-catenin, 1.6 ng; noggin, 15–50 pg; BVg1, 50–200 pg. BVg1 is a fusion protein that produces active Vg1 in the embryo. When specified, embryos were treated with 0.3 M LiCl for 6–8 min at the 32 cell stage. The phenotypes of the embryos were categorized either by degree of secondary axis formation: complete, two complete heads; incomplete, the second head possesses an incomplete complement of cement gland and eyes; or vestigial, the secondary axis lacks a cement gland and eyes; or a DAI number. In the DAI scale, a score of 5 is assigned to wild type and decreasing values represent progressively ventralized embryos, while increasing values represent progressively dorsalized embryos. DAI 1, no otic vesicle or retinal pigment; DAI 2, no retinal pigment; DAI 3, one eye; DAI 4, reduced head; DAI 5, wild type; DAI 6, bent; DAI 7, short body axis; DAI 8, no body axis. The data were analyzed using a stratified Wilcoxon rank-sum test with exact inference (StatXact software, Cytel Corporation). This is a non-parametric test for difference in the median of two ordered categorical responses. In the ventralization data, the DAI scores represent the ordered response; a decrease in median score is evidence of stronger, more extreme ventralization. In the rescue datasets, the responses were ordered from 1 (extreme ventralization), through 5 (normal) to 8 (extreme dorsalization), or from 1 (extreme ventralization), through 5 (normal) to complete secondary axis formation; a decrease in median response is evidence of less pronounced dorsalization and more pronounced ventralization. Stratification by the day of experiment was used to adjust for the day-to-day variability of the embryos. As the microinjections were found to increase ventralization/decrease dorsalization, that is, only to decrease the median response, one-sided p values are reported.

Xenopus egg extract preparation

Xenopus egg extracts were prepared according to the method of Murray et al. (1989), with modifications. Eggs were squeezed into 100 mM NaCl. After dejellying, eggs were packed for 30 s at 80 g and then crushed at 14 900 g for 10 min in a refrigerated microcentrifuge. The cytoplasmic layer was removed and spun twice at 14 900 g, each for 10 min. The extracts were supplemented with 1/20th volume of energy mix (150 mM creatine phosphate, 20 mM ATP, 2 mM EGTA, 20 mM MgCl2), protease inhibitors (chymostatin, leupeptin and pepstatin, each at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml) and cytochalasin B at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml. The resulting extracts were either used immediately or snap-frozen and stored at –80°C until use.

RNA translation in egg extracts

RNA was prepared as described above. One microgram of RNA was mixed with 25 µl of fresh extract and 1 µl RNasin (Promega) and incubated at room temperature for 2 h for translation. Semiquantitative immunoblots revealed expression levels of hB56α to be ∼1.3 µM, while sm t was expressed at ∼0.35 µM.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Freshly made egg extracts were programmed to translate Myc-axin and/or 4HA-B56α RNA. The extracts were then diluted 1:5 in IP buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM EDTA, plus Complete protease inhibitors (Boehringer Mannheim)]. Immunoprecipitation was accomplished with either anti-Myc 9E10 antibody and protein G Sepharose or 9E10-coupled Sepharose beads. Precipitates were washed three times, each with 1 ml IP buffer for 5 min, and subjected to SDS–PAGE and western blot analysis.

In vitro β-catenin degradation assay

Degradation assays were performed as described (Salic et al., 2000), with minor modifications. Reactions were set up on ice in a final volume of 30 µl, containing 25 µl egg extract, 1 µl of 10 mg/ml bovine ubiquitin in XB buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.7, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 mM sucrose) and 1 µl of [35S]β-catenin synthesized using the TNT kit (Promega). Okadaic acid, microcystin-LR or I-2 were pre-incubated with egg extracts on ice for 30 min prior to the degradation assay. Reactions were incubated at room temperature and 3 µl samples were removed at 0, 1 and 3 h. Samples were analyzed by 10% SDS–PAGE, imaged using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager and quantitated using ImageQuant software. The degradation of control substrates was assessed under the same conditions. For depletions, a 200 µl aliquot of egg extract was incubated with 80 µl of 50% microcystin-LR–Sepharose (Upstate Biotechnology). After incubation for 1 h at 4°C, the mixture was centrifuged at 800 g for 3 min at 4°C. The supernatants were removed and immediately used for the degradation assay. Mock depletion was carried out with uncoupled Sepharose beads under the same conditions. Purified PP2A C (Cegielska et al., 1994) or PP1 C (New England Biolabs) at a concentration of 1.1 µM was pre-incubated with extracts for 30 min on ice prior to the degradation assay.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank K.Kramer, B.Branford and C.Rote for assistance with microinjections; B.Smiley for RNA preparations; D.Mahaffey for help with preparation of egg extracts; A.Szabo and the Biostatistics Shared Resource for the statistical analyses of the microinjection data; A.Branscomb for critically reading the manuscript; and B.Hemmings, G.Walter, D.Pallas, R.Moon, N.Matsunami, K.Rundell, M.Movsesian, P.Polakis and M.Rechsteiner for reagents. This work was supported by NIH grant RO1CA80809, Cancer Training grant T32CA09602, and the Huntsman Cancer Institute. H.J.Y. was supported by a grant from NIH/HLBI and an AHA Established Investigator Award.

References

- Baharians Z. and Schonthal,A.H. (1998) Autoregulation of protein phosphatase type 2A expression. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 19019–19024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N., Morin,P.J. and Clevers,H. (2000) The Yin–Yang of TCF/β-catenin signaling. Adv. Cancer Res., 77, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M., Cayla,X., Van Hoof,C., Hemmings,B.A., Ozon,R., Merlevede,W. and Goris,J. (1995) The PR55 and PR65 subunits of protein phosphatase 2A from Xenopus laevis—molecular cloning and developmental regulation of expression. Eur. J. Biochem., 230, 1037–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis N.D., Street,A.J., Prescott,A.R. and Cohen,P.T. (1993) PPX, a novel protein serine/threonine phosphatase localized to centrosomes. EMBO J., 12, 987–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin G.A. et al. (2000) Low frequency of alterations of the α (PPP2R1A) and β (PPP2R1B) isoforms of the subunit A of the serine-threonine phosphatase 2A in human neoplasms. Oncogene, 19, 1191–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos M., Fadden,P., Alms,G., Qian,Z. and Haystead,T.A. (1996) Identification of protein phosphatase-1-binding proteins by microcystin–biotin affinity chromatography. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 28478–28484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cegielska A., Shaffer,S., Derua,R., Goris,J. and Virshup,D.M. (1994) Different oligomeric forms of protein phosphatase 2A activate and inhibit simian virus 40 DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 4616–4623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.X., McPartlin,A.E., Brown,L., Chen,Y.H., Barker,H.M. and Cohen,P.T. (1994) A novel human protein serine/threonine phosphatase, which possesses four tetratricopeptide repeat motifs and localizes to the nucleus. EMBO J., 13, 4278–4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding V.W., Chen,R.H. and McCormick,F. (2000) Differential regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β by insulin and wnt signaling. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 32475–32481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagotto F., Guger,K. and Gumbiner,B.M. (1997) Induction of the primary dorsalizing center in Xenopus by the Wnt/GSK/β-catenin signaling pathway, but not by Vg1, Activin or Noggin. Development, 124, 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz J., Probst,A., Ehler,E., Hemmings,B. and Kues,W. (1998) Delayed embryonic lethality in mice lacking protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit Cα. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 12370–12375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix P., Turowski,P., Mayer-Jaekel,R.E., Goris,J., Hofsteenge,J., Merlevede,W. and Hemmings,B.A. (1993) Analysis of subunit isoforms in protein phosphatase 2A holoenzymes from rabbit and Xenopus. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 7330–7337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu W., Zeng,L. and Costantini,F. (1999) Identification of a domain of axin that binds to the serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A and a self-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 3439–3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda S., Kishida,S., Yamamoto,H., Murai,H., Koyama,S. and Kikuchi,A. (1998) Axin, a negative regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway, forms a complex with GSK-3β and β-catenin and promotes GSK-3β-dependent phosphorylation of β-catenin. EMBO J., 17, 1371–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda S., Kishida,M., Matsuura,Y., Usui,H. and Kikuchi,A. (2000) GSK-3β-dependent phosphorylation of adenomatous polyposis coli gene product can be modulated by β-catenin and protein phosphatase 2A complexed with axin. Oncogene, 19, 537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas M., Tomlinson,I.P., Rowan,A., Pignatelli,M. and Bodmer,W.F. (1997) β-catenin mutations in cell lines established from human colorectal cancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 10330–10334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens V. and Goris,J. (2001) Protein phosphatase 2A: a highly regulated family of serine/threonine phosphatases implicated in cell growth and signalling. Biochem. J., 353, 417–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao K.R. and Elinson,R.P. (1988) The entire mesodermal mantle behaves as Spemann’s organizer in dorsoanterior enhanced Xenopus laevis embryos. Dev. Biol., 127, 64–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao K.R., Masui,Y. and Elinson,R.P. (1986) Lithium induced respecificiation of pattern in Xenopus laevis embryos. Nature, 322, 371–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler K.W. and Vogelstein,B. (1996) Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell, 87, 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida S., Yamamoto,H., Ikeda,S., Kishida,M., Sakamoto,I., Koyama,S. and Kikuchi,A. (1998) Axin, a negative regulator of the wnt signaling pathway, directly interacts with adenomatous polyposis coli and regulates the stabilization of β-catenin. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 10823–10826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida S., Yamamoto,H., Hino,S., Ikeda,S., Kishida,M. and Kikuchi,A. (1999) DIX domains of Dvl and axin are necessary for protein interactions and their ability to regulate β-catenin stability. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 4414–4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X.H., Walter,J., Scheidtmann,K., Ohst,K., Newport,J. and Walter,G. (1998) Protein phosphatase 2A is required for the initiation of chromosomal DNA replication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 14693–14698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCright B., Rivers,A.M., Audlin,S. and Virshup,D.M. (1996) The B56 family of protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunits encodes differentiation-induced phosphoproteins that target PP2A to both nucleus and cytoplasm. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 22081–22089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon R.T. and Kimelman,D. (1998) From cortical rotation to organizer gene expression: toward a molecular explanation of axis specification in Xenopus. BioEssays, 20, 536–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A.W., Solomon,M.J. and Kirschner,M.W. (1989) The role of cyclin synthesis and degradation in the control of maturation promoting factor activity. Nature, 339, 280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillard L., Maniey,D., Lachaume,P., Legagneux,V. and Osborne,H.B. (2000) Identification of a C-rich element as a novel cytoplasmic polyadenylation element in Xenopus embryos. Mech. Dev., 93, 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallas D.C., Shahrik,L.K., Martin,B.L., Jaspers,S., Miller,T.B., Brautigan,D.L. and Roberts,T.M. (1990) Polyoma small and middle T antigens and SV40 small t antigen form stable complexes with protein phosphatase 2A. Cell, 60, 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peifer M. and Polakis,P. (2000) Wnt signaling in oncogenesis and embryogenesis—a look outside the nucleus. Science, 287, 1606–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price N.E. and Mumby,M.C. (2000) Effects of regulatory subunits on the kinetics of protein phosphatase 2A. Biochemistry, 39, 11312–11318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe M.J., Itoh,K. and Sokol,S.Y. (2000) A positive role for the PP2A catalytic subunit in Wnt signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 35680–35683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruediger R., Pham,H.T. and Walter,G. (2001) Disruption of protein phosphatase 2A subunit interaction in human cancers with mutations in the A α subunit gene. Oncogene, 20, 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakanaka C., Weiss,J.B. and Williams,L.T. (1998) Bridging of β-catenin and glycogen synthase kinase-3β by axin and inhibition of β-catenin-mediated transcription. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 3020–3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salic A., Lee,E., Mayer,L. and Kirschner,M.W. (2000) Control of β-catenin stability: reconstitution of the cytoplasmic steps of the Wnt pathway in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol. Cell, 5, 523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf S.R. and Gerhart,J.C. (1983) Axis determination in eggs of Xenopus laevis: a critical period before first cleavage, identified by the common effects of cold, pressure and ultraviolet irradiation. Dev. Biol., 99, 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeling J.M., Miller,J.R., Gil,R., Moon,R.T., White,R. and Virshup,D.M. (1999) Regulation of β-catenin signaling by the B56 subunit of protein phosphatase 2A. Science, 283, 2089–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidensticker M.J. and Behrens,J. (2000) Biochemical interactions in the wnt pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1495, 168–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi K., Takeichi,M., Nishida,Y., Nishi,Y. and Uemura,T. (1994) Alternative cell fate choice induced by low-level expression of a regulator of protein phosphatase 2A in the Drosophila peripheral nervous system. Development, 120, 1591–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks A.B., Morin,P.J., Vogelstein,B. and Kinzler,K.W. (1998) Mutational analysis of the APC/β-catenin/Tcf pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res., 58, 1130–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strovel E.T., Wu,D. and Sussman,D.J. (2000) Protein phosphatase 2Cα dephosphorylates axin and activates LEF-1-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 2399–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suganuma M., Tatematsu,M., Yatsunami,J., Yoshizawa,S., Okabe,S., Uemura,D. and Fujiki,H. (1992) An alternative theory of tissue specificity by tumor promotion of okadaic acid in glandular stomach of SD rats. Carcinogenesis, 13, 1841–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland C., Leighton,I.A. and Cohen,P. (1993) Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 β by phosphorylation: new kinase connections in insulin and growth-factor signalling. Biochem. J., 296, 15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi Y., Futamura,M., Yamaguchi,K., Aoki,S., Takahashi,T. and Saji,S. (2000) Alterations of the PPP2R1B gene located at 11q23 in human colorectal cancers. Gut, 47, 268–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virshup D.M. (2000) Protein phosphatase 2A: a panoply of enzymes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 12, 180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.S., Esplin,E.D., Li,J.L., Huang,L., Gazdar,A., Minna,J. and Evans,G.A. (1998) Alterations of the PPP2R1B gene in human lung and colon cancer. Science, 282, 284–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman D.A., Solomon,N.M., Chang,H.C., Karim,F.D., Therrien,M. and Rubin,G.M. (1996) Protein phosphatase 2A positively and negatively regulates Ras1-mediated photoreceptor development in Drosophila. Genes Dev., 10, 272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh G.I. and Proud,C.G. (1993) Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is rapidly inactivated in response to insulin and phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor eIF-2B. Biochem. J., 294, 625–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert K., Shibamoto,S. and Nusse,R. (1999) Wnt-induced dephos phorylation of axin releases β-catenin from the axin complex. Genes Dev., 13, 1768–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H., Kishida,S., Uochi,T., Ikeda,S., Koyama,S., Asashima,M. and Kikuchi,A. (1998) Axil, a member of the Axin family, interacts with both glycogen synthase kinase 3β and β-catenin and inhibits axis formation of Xenopus embryos. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 2867–2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H., Kishida,S., Kishida,M., Ikeda,S., Takada,S. and Kikuchi,A. (1999) Phosphorylation of axin, a Wnt signal negative regulator, by glycogen synthase kinase-3β regulates its stability. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 10681–10684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.I., Lickteig,R.L., Estes,R., Rundell,K., Walter,G. and Mumby,M.C. (1991) Control of protein phosphatase 2A by simian virus 40 small-t antigen. Mol. Cell. Biol., 11, 1988–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]