Abstract

Ectoenzymes with a catalytically active domain outside the cell surface have the potential to regulate multiple biological processes. A distinct class of copper-containing semicarbazide-sensitive monoamine oxidases, expressed on the cell surface and in soluble forms, oxidatively deaminate primary amines. Via transient covalent enzyme–substrate intermediates, this reaction results in production of aldehydes, hydrogen peroxide and ammonium, which are all biologically active substances. The physiological functions of these enzymes have remained unknown, although they have been suggested to be involved in the metabolism of biogenic amines. Recently, new roles have been proposed for these enzymes in regulation of glucose uptake and, even more surprisingly, in leukocyte–endothelial cell interactions. The emerging functions of ectoenzymes in signalling and cell–cell adhesion suggest a novel mode of molecular control of these complex processes.

Keywords: cell adhesion/leukocyte trafficking/oxygen radicals/signalling/SSAO

Introduction

Enzymes have been traditionally thought to act as catalysts in complex biochemical pathways within a cell, and they have been classified according to the nature of the enzymatic reaction they catalyse (e.g. nucleotidases, oxidases, kinases). This functional division (rather than sequence alignments) also forms the basis for the current Enzyme Commission (EC) classification (http://www.expasy.ch/enzyme/enzyme_details.html). Recently, an increasing number of enzymes are being recognized as cell surface proteins (e.g. Goding and Howard, 1998). These molecules have the capacity to catalyse enzymatic reactions in the immediate vicinity of the cell surface, and thereby regulate the concentration and functions of their substrates and end products, which are often biologically active. Consequently, ectoenzymes have been implicated in uptake and recycling of nutrients and in degradation of extracellular foreign DNA. They can also regulate cell signalling by producing or destroying nucleotides (e.g. CD73/Ecto-5′ nucleotidase dephosphorylates AMP and IMP to adenosine and inosine, respectively) or by locally activating or inactivating biologically active peptides (e.g. CD143/Angiotensin-converting enzyme is responsible for proteolytic cleavage of inactive angiotensin I to biologically active angiotensin II). However, these cell surface enzymes are often large glycoproteins themselves and hence can provide many protein domains and oligosaccharide moieties for other non-enzymatic recognition events as well. Here we summarize some of the data that have accumulated during recent years to reveal the biological function of semicarbazide-senistive amine oxidases (SSAOs), one special class of ectoenzymes.

Enzymatic classification of amine oxidases

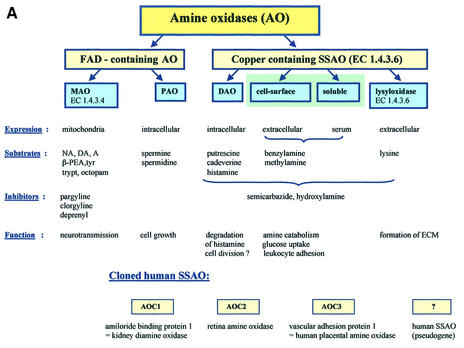

Amine oxidases (AOs) have been traditionally divided into two main groups, based on the chemical nature of the attached cofactor (Figure 1A). The flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-containing enzymes [monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A), MAO-B and polyamine oxidases] are intracellular enzymes (Shih et al., 1999). The other class of AOs contain a cofactor possessing one or more carbonyl groups, which appears to be topa-quinone (TPQ) in most cases (Klinman and Mu, 1994; Klinman, 1996; Lyles, 1996). These enzymes include diamine oxidases, lysyl oxidase, and plasma membrane and soluble MAOs. These enzymes are collectively designated as SSAOs due to their characteristic sensitivity of inhibition by a carbonyl-reactive compound, semicarbazide.

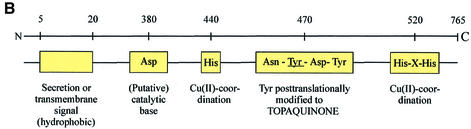

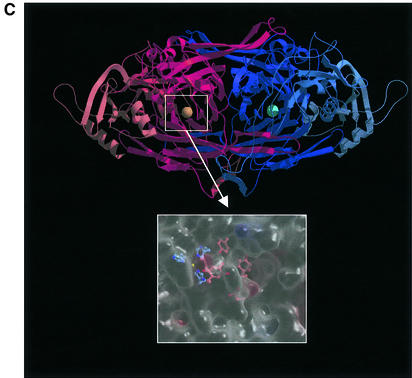

Fig. 1. (A) The classification of AOs. NA, noradrenaline; DA, dopamine; A, adrenaline; β-PEA, β-phenylethylamine; trypt, tryptamine, ECM, extracellular matrix; AOC, amine oxidase, copper-dependent. (B) The conserved motifs of SSAOs. In the N-terminus either a secretion signal or a transmembrane segment is found. The characteristic positions of the catalytic base, copper-coordinating histidines and the four amino acids-long sequence containing the tyrosine, which is modified to TPQ, as an SSAO sequence signature are shown. The line above the SSAO molecule illustrates the approximate amino acid positions of each important motif (the overall length of SSAO varies and hence the numbers are only approximations). (C) An overall fold of the catalytically active domain (D4) of a human SSAO (VAP-1). The monomers are coloured red and blue. The inset shows a closer view of the active site. The important active site residues are shown under the transparent surface. His520, His522 and His684 (blue) bind to the copper ion (yellow). The other highlighted residues are TPQ, Tyr372, Tyr384 and Asp386 (red). Figure 1C is by the courtesy of Dr Tiina Salminen, Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland.

The FAD- and TPQ-containing AOs not only differ in their cofactors, but are also distinct in terms of their subcellular distribution, substrates, inhibitors and biological functions (Figure 1). MAO-A and -B are well known mitochondrial enzymes that have firmly established roles in the metabolism of neurotransmitters (e.g. noradrenaline) and other biogenic amines (e.g. tyramine, adrenaline) (Shih et al., 1999). FAD-containing polyamine oxidases use secondary amines spermine and spermidine as their preferred substrates, and thereby possibly regulate cell growth (Seiler, 1990).

On the other hand, the TPQ-containing enzyme diamine oxidase prefers diamines putrescine and cadaverine as its substrate (Buffoni, 1966; Robinson-White et al., 1985; Barbry et al., 1990). Diamine oxidase is mainly an intracellular enzyme preferentially synthesized in the placenta, kidney and intestine. The secreted form binds in a heparin-dependent manner to endothelial cells. Diamine oxidase also oxidizes histamine, and hence is important in regulating inflammation and allergic reactions. In fact, it was first described as an amiloride binding protein believed to function as a sodium channel in human kidney (Barbry et al., 1990), and only later found to be a semicarbazide-sensitive diamine oxidase (Mu et al., 1994; Novotny et al., 1994).

The other topa-containing SSAOs are mostly soluble or expressed on the cell surface, have different preferred substrates, are insensitive or only weakly sensitive to classical MAO inhibitors (like chlorgyline or deprenyl), and mediate different biological functions (Lyles, 1996). The rest of this review will only discuss these extracellular MAOs. Moreover, although these SSAOs are present in bacteria, yeasts and plants, as well as in higher eukaryotes, we will restrict the discussion mainly to the mammalian enzymes.

SSAOs have been historically defined by their inhibition with carbonyl-reactive compounds like semicarbazide (Tabor et al., 1954). Thereafter, multiple other SSAO inhibitors have been described (reviewed in Lyles, 1996). Notably, a simple compound hydroxylamine (NH2-OH) is a more selective and potent SSAO inhibitor. Various other compounds, including propargylamine (acetylenic aliphatic amine), aminoguanidine (nitric oxide synthase inhibitor), carbidopa (DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor) and procarbazine (carcinostatic agent) are also inhibitors of SSAOs, although far from specific. Interestingly, several drugs in clinical use (e.g. an anti-microbe isoniazid, anti-hypertensive hydralazine, anti-arrythmic mexiletine) also inhibit SSAOs. In most cases, however, the contribution of SSAO inhibition to the biological effects of these drugs remains undefined. More recently some potentially more selective SSAO inhibitors like B24 (3,5-ethoxy-4-aminomethylpyridine) and MDL72274 have been developed (Lyles, 1996).

SSAO protein sequences reveal conserved motifs

In mammals the SSAO field has been hampered by the fact that the molecular identity of the enzymes has not been known. Instead, the SSAO activity has been determined merely by measuring enzymatic AO activity in cells, tissues and body fluids. Gratifyingly, during recent years, several SSAO species have been cloned from humans and rodents, which helps to ascribe certain functions to individual molecules. Determination of the SSAO cDNAs has also started to unify the chaotic descriptive nomenclature in the field.

Most SSAOs are dimeric glycoproteins with molecular masses of 140–180 kDa (Klinman and Mu, 1994; Lyles, 1996). SSAOs contain two atoms of copper per dimer. Their molecular characterization started with isolation of the molecules based on the physicochemical properties and AO activity. Early on, profound interest has been in the determination of chemical identity of the prosthetic groups of these enzymes (Klinman, 1996). Initially, pyrroloquinoline quinone was errorneously reported to be the redox cofactor associated with bovine serum SSAO (Lobenstein-Verbeek et al., 1984). When proteolytic products of the active site peptides were finally obtained in sufficient quantities, an amino acid sequence LNXPY was obtained and the unknown amino acid was identified as 6-hydroxydopa (2,4,5-trihydroxyphenylalanine quinone or TPQ) (Janes et al., 1990; Klinman, 1996). TPQ is generated from an intrinsic tyrosine of the molecule by a self-processing event that only requires bound copper ion and molecular oxygen (Mu et al., 1992).

Currently full-length cDNA sequences are available from seven mammalian SSAOs. The first monoamine SSAO enzyme has been cloned from bovine liver and encodes the bovine serum amine oxidase (BSAO) (Mu et al., 1992). A human SSAO was then cloned by two independent groups under two different names, human placental amine oxidase (Zhang and McIntire, 1996) and vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1; see below; Smith et al., 1998). Later, a retina-specific SSAO with alternatively spliced variants (designed RAO) (Imamura et al., 1997, 1998) and another SSAO, which is apparently a pseudogene (Cronin et al., 1998), have been reported. In fact, these three human SSAOs were the only ones identified from the recently published sequence of the human genome, and they all cluster in the long arm of chromosome 17. The mouse and rat homologues of human VAP-1 have also been cloned (Morris et al., 1997; Bono et al., 1998a,b; Moldes et al., 1999). In addition, the sequences of human and rat amiloride binding proteins (Lingueglia et al., 1993) are known (see above). In bovine tissues, there is genetic evidence for at least three SSAOs (Høgdall et al., 1998), suggesting that these enzymes form a multimember family. The degree of amino acid identity among the enzymes isolated from the same cellular origin is high between the species. In contrast, intra- and extracellular enzymes within one species differ more in sequence.

Most SSAOs contain the conserved signature motif (hydrophobic residue-Asn-Topa-Asp/Glu-Tyr) at the active site of the enzyme (Klinman and Mu, 1994; Salminen et al., 1998). Tyrosine is always a precursor for the topa in the sequence (Mu et al., 1992). There are three conserved histidines in SSAOs, which coordinate the copper atoms. One His-X-His motif ∼50 residues C-terminal from the cofactor and another histidine 20–30 residues toward the N-terminus from the cofactor are conserved in all alignments, despite the variations in the length of whole sequences. Moreover, a conserved Asp residue ∼100 residues N-terminal from the topa is important, since it serves as a catalytic base in the reductive half-reaction (see below). The most important structural motifs of SSAOs are illustrated in Figure 1B.

Initial sequence analyses predicted the presence of a secretion signal in all SSAOs, including placental AO. Therefore, the mechanism by which these enzymes were inserted into the plasma membrane remained unknown for a long time. Finally, epitope-tagged recombinant proteins revealed that, at least in VAP-1, the predicted secretion signal is, in fact, a transmembrane segment (Smith et al., 1998). Hence, VAP-1 is a type 2 transmembrane protein with a very short (4 amino acids) N-terminal cytoplasmic tail, a single transmembrane segment and a large extracellular segment.

A few SSAOs from bacteria have been purified for crystallography. A well characterized Escherichia coli SSAO contains four domains and displays a mushroom-like shape (Parsons et al., 1995). A 400 amino acids-long C-terminal β-sandwich domain contains the active site and forms much of the dimer interface. Notably, the β-sandwich core is a novel protein fold. The three other α/β-domains are shorter (∼100 amino acids each). The dimeric structure is held together by connection, with covalent and non-covalent interactions, of a pair of β-hairpin turns. The active sites are deeply buried within the molecule, but the only notable changes in structures between inactive (in the absence of substrate) and active enzyme are differences in copper coordination geometry and the position and interactions of TPQ within the active centre. Molecular modelling suggests that VAP-1 is also a mushroom-shaped molecule (Figure 1C) (Salminen et al., 1998).

Semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase exists in soluble form(s) as well as in a membrane-bound form (Lyles, 1996). There has been considerable disagreement as to whether the soluble form is a product of a different gene or a cleavage product of the transmembrane form of SSAO. In man there is evidence that the soluble enzyme is formed by a proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound molecule, since the N-terminal sequence of the soluble form isolated from the serum is identical to the membrane distal sequence of the VAP-1. In fact, in man most, if not all, AO activity in serum is mediated by soluble SSAO, which was identified as VAP-1 (Kurkijärvi et al., 2000). In other animals, the situation may well be different, since kinetic data suggest the existence of two different soluble SSAO enzymes in sheep (Elliott et al., 1992; Boomsma et al., 2000). Furthermore, the BSAO gene encoding a soluble form of SSAO in bovine has been cloned (Mu et al., 1994).

The deamination reaction

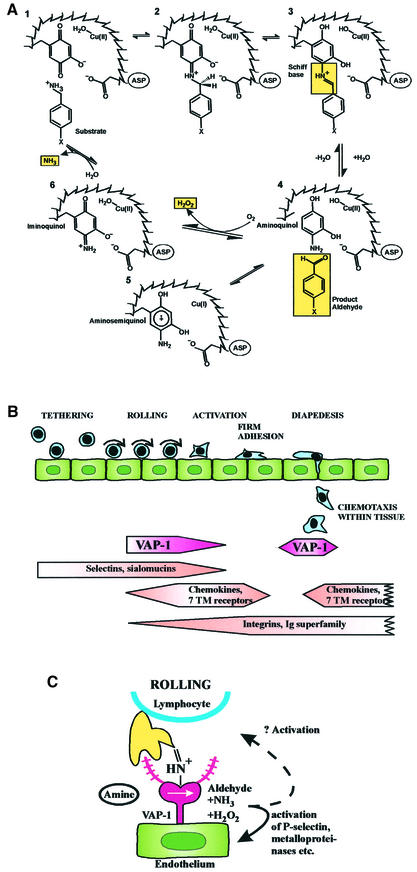

All SSAOs catalyse oxidative deamination of primary amines in a reaction: R-CH2-NH2 + O2 + H2O→R-CHO + H2O2 + NH3 (reviewed in Klinman and Mu, 1994; Wilmot et al., 1999). The kinetic reaction consists of two half-reactions (Figure 2A). First, the enzyme is reduced by the substrate with simultaneous release of the corresponding aldehyde. In the second part, the enzyme is reoxidated by molecular oxygen with concomitant release of hydrogen peroxide and ammonium.

Fig. 2. The SSAO reaction and leukocyte extravasation. (A) The catalytic reaction of SSAO. In the reductive half-reaction (1–4) the primary amine group interacts with the TPQ of the enzyme. Then a proton is abstracted by the active-site base (aspartate) and, through a carbanionic intermediate, a product Schiff base is formed. Thereafter, hydrolysis occurs, the product aldehyde is released and the reduced cofactor is left attached to enzyme mainly in an aminoquinol-Cu2+ form. In the oxidative half-reaction (5, 6, 1) the reduced enzyme is recycled to the resting state via an iminoquinol intermediate in a copper- and molecular oxygen-dependent reaction. During this half-reaction, hydrogen peroxide and ammonia are released. (B) The leukocyte extravasation cascade. The different steps of the adhesion cascade and the involvement of VAP-1 are shown. (C) The oligosaccahride modifications of VAP-1 (purple extensions) can bind to an unknown lectin-like molecule (yellow) on lymphocytes. Alternatively, when endothelial VAP-1 uses a lymphocyte surface amine as a substrate, the catalytic reaction results in the formation of a transient covalent bond (step 3 in A) between the two cell types. This enzymatic reaction seems to be involved in the binding during the rolling step. The oligosaccharide and Schiff-base mediated bindings can involve separate molecules on the lymphocyte surface or, if the lectin-type lymphocyte surface molecule also presents the amine to VAP-1, the same molecule may be used in both steps.

Reductive inactivation experiments showed that the substrate was trapped in a covalent bond to the enzyme (Hartmann and Klinman, 1987). Nowadays there is direct evidence that the reductive half-reaction involves sequential formation of multiple transition stages during which a transient but covalent Schiff base is formed between the enzyme and the substrate before the product aldehyde is released (Dooley et al., 1991; Hartmann et al., 1993) (Figure 2A). During the oxidative half-reaction, the reduced cofactor recycles back to its oxidized TPQ form. During this process hydrogen peroxide and ammonia are released.

It is generally agreed that SSAOs only accept primary amines as substrates, although there may be exceptions to this rule (Yu and Davis, 1990). Nevertheless, there appears to be wide variation among the preferred substrates in different species (Lyles, 1996). Benzylamine, an artificial amine, is the preferred substrate for most, if not all, SSAOs. In addition, in humans methylamine and allylamine are accepted as SSAO substrates, but in many rodents tyramine, tryptamine, histamine and β-phenylethylamine are also oxidatively deaminated by SSAOs. Therefore, some caution must be exerted in generalizing results with SSAOs obtained from different species.

SSAOs and catabolism of biogenic amines

Human SSAO can use xenobiotic amines like allylamine as substrates (Lyles, 1996). During this reaction, these compounds are converted to considerably more toxic products (like acrolein from allylamine; Boor et al., 1990) than the relatively harmless substrates themselves. Hence, SSAO reactions may account for atherosclerotic lesions seen in animals exposed to these amines.

Also, at least two endogenously formed amines can serve as SSAO substrates. Thus, oxidation of methylamine, which is formed during degradation of sarcosine, creatinine and adrenaline, results in formation of formaldehyde (McEwen and Harrison, 1965). On the other hand, the end products of SSAO-catalysed deamination of aminoacetone, which is derived from metabolism of glycine and threonine, is methylglyoxal (Lyles and Chalmers, 1992). Again, the resulting aldehydes are much more toxic than the parent compounds (Yu and Zuo, 1996) and the physiological significance of these reactions remains unknown.

All products of the SSAO-catalysed reaction are biologically active. Probably the most interesting of the end-products is hydrogen peroxide. This reactive oxygen species is toxic at high concentration. However, at lower concentrations it is becoming increasingly recognized as a signal-transducing molecule (Finkel, 1998; Kunsch and Medford, 1999; Bogdan et al., 2000). Thus, hydrogen peroxide known to regulate the function of transcription factors, like NF-κB, and hence expression of many genes (including chemokines, adhesion molecules, cytokines and metalloproteinases). In the vascular wall hydrogen peroxide regulates proliferation and adhesive properties of both endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells.

Functions of membrane-bound SSAO

The biological role of SSAOs (reviewed in Klinman and Mu, 1994), with the exception of lysyl oxidase, has remained enigmatic for decades in mammals. In bacteria and yeast, the SSAO reaction provides these microbes with a source of nitrogen (and carbon) when growing in the presence of various amines. In plants, on the other hand, the hydrogen peroxide released from the SSAO-catalysed reaction is used for wound healing. In mammals, the speculative functions of SSAOs have focused on their role in metabolism of exogenous or endogenous amines (see above), although the significance of this reaction is far from clear.

SSAOs are widely expressed in mammals (Lewinsohn, 1984; Salmi et al., 1993; Lyles, 1996; Jaakkola et al., 1999). Based on enzymatic analyses, and confirmed with stainings of monoclonal anti-VAP-1 mAbs, the most prominent synthesis takes place in smooth muscle (both vascular and non-vascular) and adipocytes, but endothelial cells and follicular dendritic cells are also positive for VAP-1. In contrast, leukocytes, epithelial and fibroblastoid cells are completely devoid of VAP-1. Notably, SSAO is also absent from brain (except microvessels). In humans, VAP-1 is also absent from chondrocytes and odontoblasts, which have been reported to display SSAO activity in other animals.

Quite recently, two totally new and different functions for SSAOs have been proposed: they seem to be involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism in adipose cells and in the regulation of leukocyte trafficking in endothelial cells.

SSAOs and glucose metabolism

SSAOs account for ∼1% of total adipocyte membrane proteins, and its level is upregulated concordantly with adipocyte differentiation (Morris et al., 1997; Enrique-Tarancón et al., 1998; Moldes et al., 1999). Thus, preadipocytes are practically SSAO negative, whereas mature adipocytes express high levels of SSAO protein and activity, which co-localizes with GLUT4 vesicles. When an artificial SSAO substrate benzylamine is provided to mature adipocytes, glucose uptake is significantly enchanced via a GLUT4-dependent mechanism. This metabolic effect apparently depends on hydrogen peroxide formed, which may regulate trafficking of the glucose transporter GLUT4 to the plasma membrane. The effect of SSAO activity on glucose metabolism and on stimulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins and on activity of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase has earlier only been seen in the presence of vanadate, a potent phosphatase inhibitor (Enrique-Tarancón et al., 1998, 2000). However, very recent evidence shows that glucose transport is increased in human adipocytes in the presence of SSAO substrates alone, which makes the biological significance of these observations even more evident (Morin et al., 2001).

SSAO/VAP-1 acts as an endothelial adhesion molecule for leukocytes

Another line of investigation has surprisingly identified an SSAO as an adhesion molecule involved in leukocyte trafficking. This process consists of a multistep adhesion cascade (Springer, 1994; Butcher and Picker, 1996; Salmi and Jalkanen, 1997). Blood-borne leukocytes first reversibly tether to and roll on the endothelial cells under conditions of blood flow. If they receive appropriate activation signals, they can then firmly adhere to the vessel wall and transmigrate into the tissue. Multiple adhesion and activation molecules on leukocyte and endothelial cell side regulate the molecular execution of this orchestrated process (Figure 2B).

Using a mAb-based approach, an apparently novel endothelial molecule designated VAP-1 was reported. It mediates leukocyte binding in adhesion assays under shear (Salmi and Jalkanen, 1992). VAP-1 is constitutively present in intracellular granules within endothelial cells (Salmi et al., 1993). However, with in vivo inflammation models, VAP-1 seems to be translocated lumenally from intracellular storage granules only upon elicition of inflammation (Jaakkola et al., 2000). VAP-1 mediates leukocyte subtype-specific adhesion (Salmi et al., 1997). Among mononuclear cells, the VAP-1-dependent pathway is important for binding of CD8-positive T killer cells and natural killer cells, but not of B cells, T helper cells or monocytes. VAP-1 is also present on sinusoidal endothelial cells in liver, which is a unique cell type supporting leukocyte trafficking to this large immunocompetent organ (McNab et al., 1996). Sinusoidal VAP-1 also supports lymphocyte adhesion in various adhesion assays (McNab et al., 1996; Yoong et al., 1998). In animal studies, anti-VAP mAbs efficiently inhibit (∼70%) granulocyte extravasation into areas of acute inflammation (Tohka et al., 2001). Finally, in intravital microscopy, the VAP-1 molecule first seems to be important for the rolling phase and most likely later at the transmigration step of leukocyte extravasation (Tohka et al., 2001).

When VAP-1 was cloned, it revealed surprising sequence identity to SSAOs (Smith et al., 1998). Experiments with recombinant VAP-1 revealed that it indeed possessed MAO activity with benzylamine and methylamine being the preferred substrates. Very recently, evidence has been obtained that the SSAO-catalysed enzymatic reaction per se may be important for leukocyte adhesion (Salmi et al., 2001). In parallel plate flow chamber analyses, VAP-1-positive endothelial cells support lymphocyte rolling and firm adhesion in a VAP-1-dependent manner. Although the anti-VAP-1 mAbs inhibit lymphocyte rolling, they do not inhibit the SSAO activity of this dual function molecule. Most intriguingly, the inclusion of chemical SSAO inhibitors specifically abrogated ∼50% of lymphocyte rolling and firm adhesion under physiological flow. In contrast, inclusion of soluble reaction products (hydrogen peroxide or benzaldehyde) to the system did not inhibit lymphocyte–endothelial cell interactions. Finally, provision of additional soluble SSAO substrate for the reaction surprisingly inhibited rather than augmented lymphocyte adherence. These data suggested that a transient covalent bond may be formed between the enzyme (endothelial VAP-1) and substrate during the multistep extravasation cascade. Notably, a lymphoid cell-surface bound rather than a soluble amine had to be postulated to be the SSAO substrate in this case to explain the observations. This hypothesis was further substantiated by the finding that a synthetic peptide can fit into the surface groove of VAP-1 and indeed modulate the SSAO activity of VAP-1 by binding to the catalytic cavity (Salmi et al., 2001). Thus, it is possible that surface bound amines (like N-termini of proteins, NH2-containing amino acid side chains, amino sugars etc.) may be SSAO substrates in addition to soluble amines. Furthermore, this SSAO function suggests a new way in which an endothelial ecto-enzyme can directly regulate the leukocyte extravasation. Moreover, these data suggest that VAP-1 is a dual function molecule: it binds lymphocytes via an anti-VAP-1 mAb-defined epitope and subsequently utilizes the catalytic reaction between a surface-bound amine and VAP-1 to transiently link the interacting cells under physiological flow conditions. After the Schiff base step of the enzymatic reaction (Figure 2A, step 3) has rapidly turned over, the VAP-1-catalysed reaction may further contribute to cross-linking if the protein-bound aldehydes formed on lymphocytes interact with molecules on endothelial cell surface.

Biological functions for soluble SSAOs

For the soluble SSAO at least two functions have so far been proposed. First, increased levels of soluble serum SSAO are found in specific diseases, most notably in certain liver disorders and in diabetes (Garpenstrand et al., 1999; Kurkijärvi et al., 2000). In diabetes there is evidence that SSAO activity may cause the atherogenic lesions typical of this disorder by catalysing extensive formation of aldhehydes and reactive oxygen species from soluble substrates (Yu and Deng, 1998). It may also be involved in the production of non-enzymatic addition of oligosaccharides to proteins during formation of advanced glycosylation end products, typical of diabetic lesions (Yu and Zuo, 1993, 1997). On the other hand, soluble SSAO has been shown to modulate lymphocyte adhesion to endothelial cells (Kurkijärvi et al., 1998), presumably by triggering positive signals on the lymphocyte.

Lysyl oxidase—a special case

Lysyl oxidase is unique amongst the SSAO family of enzymes (Smith-Mungo and Kagan, 1998). Although it is sensitive to SSAO inhibitors, it is considerably smaller than the other SSAOs, its primary sequence lacks certain critical motifs (e.g. the copper-coordinating histidines) and its cofactor appears to be lysine tyrosylquinone rather than TPQ (Wang et al., 1997). In fact, its classification is constantly under dispute. This molecule has a well established role in cross-linking collagen and elastin during the formation of extracellular matrix. Intri guingly, epsilon amino groups of lysine are known substrates for this SSAO (Kagan et al., 1984), and it exerts its function through covalent cross-linking of two molecules (which then proceeds to a permanent linkage by autocondensation). Hence, the molecular mechanism of this enzyme is notably comparable to that proposed for VAP-1 in leukocyte extravasation (see above).

Conclusions

SSAOs have been characterized by enzymatic means for decades in serum as well as in multiple cell and tissue types in various species. Based on this work, we currently have a detailed understanding of the kinetic reaction these enzymes catalyse. During the last 10 years, molecular identification of distinct SSAO species by molecular cloning has opened new avenues for understanding the biological functions of these abundant enzymes. One of the most compelling questions at the moment is the nature of physiological SSAO substrates. Moreover, there is now evidence emerging that the function of SSAO may be dependent on the cell type on which they are expressed. In addition to functions connected to the catabolism of exo- and endogenous biogenic amines, these enzymes may play other roles as well. Notably, the possible functions of SSAO end products in glucose metabolism and SSAO-dependent Schiff-base formation in leukocyte trafficking are just two exciting examples of how the ectoenzymes may regulate signalling and adhesion processes. SSAO transgenic and knock-out animals have been generated, and are currently under analysis. This should provide clear answers to the questions of how individual SSAO molecules contribute to various physiological and pathological functions in vascular biology and related areas.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Prof. J.Klinman, Prof. K.Tipton and Dr Gennady Yegutkin for advice and critical reading of this manuscript. The contribution of Prof. Klinman and Dr Diana Wertz in drawing Figure 2A is especially highly appreciated. The enzymatic characterization of SSAOs in multiple species has been described in hundreds of reports during the last decades, and we have only been able to refer to a minor fraction of these papers in this short review. The help of Mrs Anne Sovikoski-Georgieva in preparing the manuscript is acknowledged. The original VAP-1/SSAO work has been supported by the Finnish Academy, the European Union (QLG7-CT-1999–00295), the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Finnish Cultural Foundation and the Finnish Cancer Union.

References

- Barbry P. et al. (1990) Human kidney amiloride-binding protein: cDNA structure and functional expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 7347–7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan C., Röllinghoff,M. and Diefenbach,A. (2000) Reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen intermediates in innate and specific immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol., 12, 64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono P., Salmi,M., Smith,D.J. and Jalkanen,S. (1998a) Cloning and characterization of mouse vascular adhesion protein-1 reveals a novel molecule with enzymatic activity. J. Immunol., 160, 5563–5571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono P., Salmi,M., Smith,D.J., Leppänen,I., Horelli-Kuitunen,N., Palotie,A. and Jalkanen,S. (1998b) Isolation, structural characterization and chromosomal mapping of the mouse vascular adhesion protein-1 gene and promoter. J. Immunol., 161, 2953–2960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma F., van Dijk,J., Bhaggoe,U.M., Bouhuizen,A.M. and van den Meiracker,A.H. (2000) Variation in semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase activity in plasma and tissues of mammals. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol., 126, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boor P.J., Hysmith,R.M. and Sanduja,R. (1990) A role for a new vascular enzyme in the metabolism of xenobiotic amines. Circ. Res., 66, 249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffoni F. (1966) Histaminase and related amine oxidases. Pharmacol. Rev., 18, 1163–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher E.C. and Picker,L.J. (1996) Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science, 272, 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin C.N., Zhang,X., Thompson,D.A. and McIntire,W.S. (1998) cDNA cloning of two splice variants of a human copper-containing monoamine oxidase pseudogene containing a dimeric Alu repeat sequence. Gene, 220, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley D.M., McGuirl,M.A., Brown,D.E., Turowski,P.N., McIntire,W.S. and Knowles,P.F. (1991) A Cu(I)-semiquinone state in substrate-reduced amine oxidases. Nature, 349, 262–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J., Callingham,B.A. and Sharman,D.F. (1992) Amine oxidase enzymes of sheep blood vessels and blood plasma: a comparison of their properties. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C, 102, 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enrique-Tarancón G. et al. (1998) Role of semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase on glucose transport and GLUT4 recruitment to the cell surface in adipose cells. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 8025–8032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enrique-Tarancón G. et al. (2000) Substrates of semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase co-operate with vanadate to stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin-receptor-substrate proteins, phospho inositide 3-kinase activity and GLUT4 translocation in adipose cells. Biochem. J., 350, 171–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T. (1998) Oxygen radicals and signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 10, 248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garpenstrand H., Ekblom,J., Bäcklund,L.B., Oreland,L. and Rosenqvist,U. (1999) Elevated plasma semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase (SSAO) activity in Type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated by retinopathy. Diabet. Med., 16, 514–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goding J.W. and Howard,M.C. (1998) Ecto-enzymes of lymphoid cells. Immunol. Rev., 161, 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann C. and Klinman,J.P. (1987) Reductive trapping of substrate to bovine plasma amine oxidase [published erratum appears in J. Biol. Chem., 1987, 262, 4427]. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 962–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann C., Brzovic,P. and Klinman,J.P. (1993) Spectroscopic detection of chemical intermediates in the reaction of para-substituted benzylamines with bovine serum amine oxidase. Biochemistry, 32, 2234–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høgdall E.V.S., Houen,G., Borre,M., Bundgaard,J.R., Larsson,L.-I. and Vuust,J. (1998) Structure and tissue-specific expression of genes encoding bovine copper amine oxidases. Eur. J. Biochem., 251, 320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura Y., Kubota,R., Wang,Y., Asakawa,S., Kudoh,J., Mashima,Y., Oguchi,Y. and Shimizu,N. (1997) Human retina-specific amine oxidase (RAO): cDNA cloning, tissue expression and chromosomal mapping. Genomics, 40, 277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura Y., Noda,S., Mashima,Y., Kudoh,J., Oguchi,Y. and Shimizu,N. (1998) Human retina-specific amine oxidase: genomic structure of the gene (AOC2), alternatively spliced variant and mRNA expression in retina. Genomics, 51, 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola K. et al. (1999) Human vascular adhesion protein-1 in smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Pathol., 155, 1953–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola K. et al. (2000) In vivo detection of vascular adhesion protein-1 in experimental inflammation. Am. J. Pathol., 157, 463–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes S.M., Mu,D., Wemmer,D., Smith,A.J., Kaur,S., Maltby,D., Burlingame,A.L. and Klinman,J.P. (1990) A new redox cofactor in eukaryotic enzymes: 6-hydroxydopa at the active site of bovine serum amine oxidase. Science, 248, 981–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan H.M., Williams,M.A., Williamson,P.R. and Anderson,J.M. (1984) Influence of sequence and charge on the specificity of lysyl oxidase toward protein and synthetic peptide substrates. J. Biol. Chem., 259, 11203–11207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinman J.P. (1996) New quinocofactors in eukaryotes. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 27189–27192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinman J.P. and Mu,D. (1994) Quinoenzymes in biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 63, 299–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunsch C. and Medford,R.M. (1999) Oxidative stress as a regulator of gene expression in the vasculature. Circ. Res., 85, 753–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurkijärvi R., Adams,D.H., Leino,R., Möttönen,T., Jalkanen,S. and Salmi,M. (1998) Circulating form of human vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1): increased serum levels in inflammatory liver diseases. J. Immunol., 161, 1549–1557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurkijärvi R., Yegutkin,G.G., Gunson,B.K., Jalkanen,S., Salmi,M. and Adams,D.H. (2000) Circulating soluble vascular adhesion protein 1 accounts for the increased serum monoamine oxidase activity in chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology, 119, 1096–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn R. (1984) Mammalian monoamine-oxidizing enzymes, with special reference to benzylamine oxidase in human tissues. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res., 17, 223–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingueglia E., Renard,S., Voilley,N., Waldmann,R., Chassande,O., Lazdunski,M. and Barbry,P. (1993) Molecular cloning and functional expression of different molecular forms of rat amiloride-binding proteins. Eur. J. Biochem., 216, 679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobenstein-Verbeek C.L., Jongejan,J.A., Frank,J. and Duine,J.A. (1984) Bovine serum amine oxidase: a mammalian enzyme having covalently bound PQQ as prosthetic group. FEBS Lett., 170, 305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles G.A. (1996) Mammalian plasma and tissue-bound semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidases: biochemical, pharmacological and toxicological aspects. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol., 28, 259–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles G.A. and Chalmers,J. (1992) The metabolism of aminoacetone to methylglyoxal by semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase in human umbilical artery. Biochem. Pharmacol., 43, 1409–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen C.M. Jr and Harrison,D.C. (1965) Abnormalities of serum monoamine oxidase in chronic congestive heart failure. J. Lab. Clin. Med., 65, 546–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNab G., Reeves,J.L., Salmi,M., Hubscher,S., Jalkanen,S. and Adams,D.H. (1996) Vascular adhesion protein 1 mediates binding of T cells to human hepatic endothelium. Gastroenterology, 110, 522–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldes M., Fève,B. and Pairault,J. (1999) Molecular cloning of a major mRNA species in murine 3T3 adipocyte lineage. Differentiation-dependent expression, regulation and identification as semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 9515–9523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin N. et al. (2001) Semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase substrates stimulate glucose transport and inhibit lipolysis in human adipocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 297, 563–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris N.J., Ducret,A., Aebersold,R., Ross,S.A., Keller,S.R. and Lienhard,G.E. (1997) Membrane amine oxidase cloning and identification as a major protein in the adipocyte plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 9388–9392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu D., Janes,S.M., Smith,A.J., Brown,D.E., Dooley,D.M. and Klinman,J.P. (1992) Tyrosine codon corresponds to topa quinone at the active site of copper amine oxidases. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 7979–7982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu D., Medzihradszky,K.F., Adams,G.W., Mayer,P., Hines,W.M., Burlingame,A.L., Smith,A.J., Cai,D. and Klinman,J.P. (1994) Primary structures for a mammalian cellular and serum copper amine oxidase. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 9926–9932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotny W.F., Chassande,O., Baker,M., Lazdunski,M. and Barbry,P. (1994) Diamine oxidase is the amiloride-binding protein and is inhibited by amiloride analogues. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 9921–9925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M.R., Convery,M.A., Wilmot,C.M., Yadav,K.D.S., Blakeley,V., Corner,A.S., Phillips,S.E.V., McPherson,M.J. and Knowles,P.F. (1995) Crystal structure of a quinoenzyme: copper amine oxidase of Escherichia coli at 2 Å resolution. Structure, 3, 1171–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-White A., Baylin,S.B., Olivecrona,T. and Beaven,M.A. (1985) Binding of diamine oxidase activity to rat and guinea pig microvascular endothelial cells. Comparisons with lipoprotein lipase binding. J. Clin. Invest., 76, 93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmi M. and Jalkanen,S. (1992) A 90-kilodalton endothelial cell molecule mediating lymphocyte binding in humans. Science, 257, 1407–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmi M. and Jalkanen,S. (1997) How do lymphocytes know where to go: current concepts and enigmas of lymphocyte homing. Adv. Immunol., 64, 139–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmi M., Kalimo,K. and Jalkanen,S. (1993) Induction and function of vascular adhesion protein-1 at sites of inflammation. J. Exp. Med., 178, 2255–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmi M., Tohka,S., Berg,E.L., Butcher,E.C. and Jalkanen,S. (1997) Vascular adhesion protein 1 (VAP-1) mediates lymphocyte subtype-specific, selectin-independent recognition of vascular endothelium in human lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med., 186, 589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmi M., Yegutkin,G., Lehvonen,R., Koskinen,K., Salminen,T. and Jalkanen,S. (2001) A cell surface amine oxidase directly controls lymphocyte migration. Immunity, 14, 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen T.A., Smith,D.J., Jalkanen,S. and Johnson,M.S. (1998) Structural model of the catalytic domain of an enzyme with cell adhesion activity: human vascular adhesion protein-1 (HVAP-1) D4 domain is an amine oxidase. Protein Eng., 11, 1195–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler N. (1990) Polyamine metabolism. Digestion, 46, 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih J.C., Chen,K. and Ridd,M.J. (1999) Monoamine oxidase: from genes to behavior. Annu. Rev. Neurosci., 22, 197–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.J., Salmi,M., Bono,P., Hellman,J., Leu,T. and Jalkanen,S. (1998) Cloning of vascular adhesion protein-1 reveals a novel multifunctional adhesion molecule. J. Exp. Med., 188, 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Mungo L.I. and Kagan,H.M. (1998) Lysyl oxidase: properties, regulation and multiple functions in biology. Matrix Biol., 16, 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer T.A. (1994) Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell, 76, 301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor C.W., Tabor,H. and Rosenthal,S.M. (1954) Purification of amine oxidase from beef plasma. J. Biol. Chem., 208, 645–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohka S., Laukkanen,M.-L., Jalkanen,S. and Salmi,M. (2001) Vascular adhesion protein 1 (VAP-1) functions as a molecular brake during granulocyte rolling and mediates their recruitment in vivo. FASEB J., 15, 373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.X., Nakamura,N., Mure,M., Klinman,J.P. and Sanders-Loehr,J. (1997) Characterization of the native lysine tyrosylquinone cofactor in lysyl oxidase by Raman spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 28841–28844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmot C.M., Hajdu,J., McPherson,M.J., Knowles,P.F. and Phillips,S.E. (1999) Visualization of dioxygen bound to copper during enzyme catalysis. Science, 286, 1724–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoong K.F., McNab,G., Hübscher,S.G. and Adams,D.H. (1998) Vascular adhesion protein-1 and ICAM-1 support the adhesion of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to tumor endothelium in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunol., 160, 3978–3988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P.H. and Davis,B.A. (1990) Some pharmacological implications of MAO-mediated deamination of branched aliphatic amines: 2-propyl-1-aminopentane and N-(2-propylpentyl)glycinamide as valproic acid precursors. J. Neural Transm. Suppl., 32, 89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P.H. and Deng,Y.L. (1998) Endogenous formaldehyde as a potential factor of vulnerability of atherosclerosis: involvement of semi carbazide-sensitive amine oxidase-mediated methylamine turnover. Atherosclerosis, 140, 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P.H. and Zuo,D.-M. (1993) Oxidative deamination of methylamine by semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase leads to cytotoxic damage in endothelial cells. Possible consequences for diabetes. Diabetes, 42, 594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P.H. and Zuo,D.M. (1996) Formaldehyde produced endogenously via deamination of methylamine. A potential risk factor for initiation of endothelial injury. Atherosclerosis, 120, 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P.H. and Zuo,D.M. (1997) Aminoguanidine inhibits semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase activity: implications for advanced glycation and diabetic complications. Diabetologia, 40, 1243–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. and McIntire,W.S. (1996) Cloning and sequencing of a copper-containing, topa quinone-containing monoamine oxidase from human placenta. Gene, 179, 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]