Abstract

Here we report the crystal structure of the DNA heptanucleotide sequence d(GCATGCT) determined to a resolution of 1.1 Å. The sequence folds into a complementary loop structure generating several unusual base pairings and is stabilised through cobalt hexammine and highly defined water sites. The single stranded loop is bound together through the G(N2)–C(O2) intra-strand H-bonds for the available G/C residues, which form further Watson–Crick pairings to a complementary sequence, through 2-fold symmetry, generating a pair of non-planar quadruplexes at the heart of the structure. Further, four adenine residues stack in pairs at one end, H-bonding through their N7–N6 positions, and are additionally stabilised through two highly conserved water positions at the structural terminus. This conformation is achieved through the rotation of the central thymine base at the pinnacle of the loop structure, where it stacks with an adjacent thymine residue within the lattice. The crystal packing yields two halved biological units, each related across a 2-fold symmetry axis spanning a cobalt hexammine residue between them, which stabilises the quadruplex structure through H-bonds to the phosphate oxygens and localised hydration.

INTRODUCTION

In 1953 Watson and Crick wrote of the structure of DNA (1) and the manner in which the purine and pyrimidine bases are held together through their regular H-bonding patterns, a model which has become ubiquitous within modern science. Today however, it has become clear that the regular model of DNA shown in most texts is not as perfect as originally supposed. The number of structural solutions escalate each year and those at atomic resolution reveal much more of the structural diversity associated with this highly flexible biopolymer (2,3). These studies have revealed that alongside the regular Watson–Crick base pairings a plethora of non-canonical combinations also exist, illustrating the multi-functional roles DNA can play (4–7).

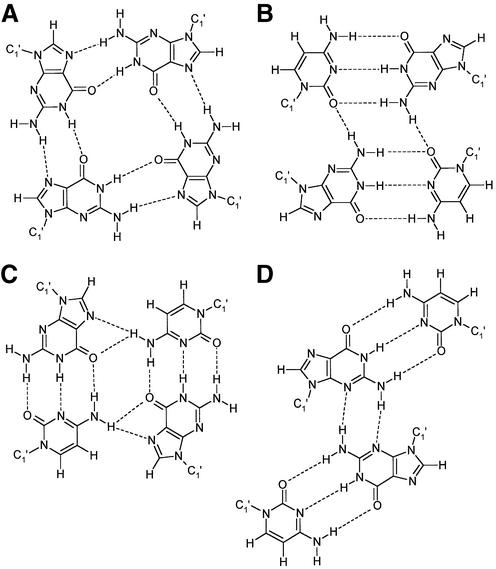

DNA is a highly polymorphic molecule capable of huge conformational changes and forming numerous structural motifs. One class of such structures are DNA quadruplexes, of which the Hoogsteen paired coplanar guanine tetrad (Fig. 1A) is amongst the most studied (6,8–15). The accumulating evidence appearing in the literature (16–18), regarding its biological significance would seem to provide compelling support for the existence and functions of quadruplex structures within biological systems, making it an attractive therapeutic target (19). The DNA target involved is telomeric DNA, which consist of single stranded, guanine rich sequences, found at the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes that have now been shown through numerous structural examples, capable of folding into quadruplex structure in vitro. Alongside this many examples are appearing of small organic molecules, such as the anthraquinones and porphyrins, capable of targeting these telomeres, through stacking interactions within the guanine quadruplex (20–23). It should be noted however that multiple guanines are not the only nucleotides that can be shown to produce quadruplex structure (Fig. 1). The original structure solution of the heptamer d(GCATGCT) by Hunter et al., solved to a resolution of 1.8 Å (24), illustrated this to be true (Fig. 1B) with the existence of a non-planar G/C quadruplex. Further studies of G/C quadruplex formation (25,26) have revealed a more tightly bound planar tetrad (Fig. 1C), and more recently several examples (27–29) showing drug binding to the hexamer sequence d(CGTACG) have shown a G/C tetraplex structure and the role of intercalating chromophores in the stabilisation of the greatly enlarged nucleotide tetrad intercalation site (Fig. 1D). Alongside these, the octamer sequence bi-loop structure d(ATTCATTC) was determined by Pedroso et al. to a resolution of 1.1 Å (30) with no guanine nucleotides present, although no true quadruplex is formed within this lattice. The latter structure is not known so far in vivo, although the importance of non-duplex DNA is increasingly recognised (31).

Figure 1.

Schematic views of (A) the G/G quadruplex, (B) the G/C quadruplex observed here, (C) the planar G/C quadruplex, (D) the slipped alignment G/C nucleotide tetrad.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The synthetic DNA heptamer d(GCATGCT) was purchased from Oswel DNA services and crystals were grown by vapour diffusion, using conditions optimised from the Hampton Research nucleic acid mini-screening kit at 290 K from sitting drops containing 2 µl 40 mM sodium cacodylate, 1 µl 80 mM cobalt hexammine, 1 µl 10% 2-methyl-2,4-methylpentanediol (MPD), 2 µl 800 mM potassium chloride, 1 µl 30 mM sodium chloride, 2 µl 1 mM DNA and equilibrated against a 1 ml reservoir of 30% MPD. Small rods appeared within 10 days and grew to an optimal size of 0.5 × 0.2 × 0.2 mm within 30 days. Synchrotron diffraction data was collected on beam line X11 at 100 K on the EMBL outstation, DESY, Hamburg. A MAR Research CCD was used as the detector to collect highly redundant data to a resolution of 1.1 Å, which was subsequently processed and scaled using XDS (32) (Table 1). The structure was solved through molecular replacement using the CCP4 version of MOLREP (33) with two of the asymmetric units from the Hunter et al. model (NDB code UDG028) (24), to yield an R-factor of 0.504 and a correlation coefficient of 0.688. Anisotropic structural refinement was carried out with SHELX-97 (34), model building and water divining with XTALVIEW (35) from sigma-A and difference maps calculated with SHELXPRO, to yield a final R-factor of 21.26% and R-free of 22.40%. The structure solution was deposited with the NDB under the code UD0022. All r.m.s. deviation calculations between structural models were carried out with ProFit V2.2 (www.bioinf.org.uk/software/profit).

Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Spacegroup | C2221 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a = 22.128 |

| b = 59.215 | |

| c = 45.784 | |

| λ (Å) | 0.811 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 20–1.1 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.3 (99.4) |

| Reflections (unique) | 12 514 (2803) |

| Redundancy | 7.70 (6.64) |

| Ave I/σ | 10.96 (5.24) |

| R-merge | 0.11 (0.37) |

| R-factor (%) | 21.26 (20.80) |

| R-free (%) | 22.40 (21.73) |

| Nucleic acid atoms | 280 |

| Heterogen atoms | 7 |

| Solvent atoms | 38 |

| r.m.s. bond deviation (Å) | 0.018 |

| r.m.s. angle deviation (°) | 0.035 |

| Average DNA B (Å2) | 20.94 |

| Average solvent B (Å2) | 27.27 |

Values in parenthesis apply to the outer resolution shell 1.2–1.1 Å.

RESULTS

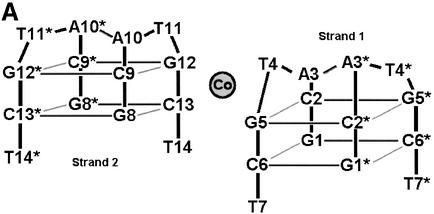

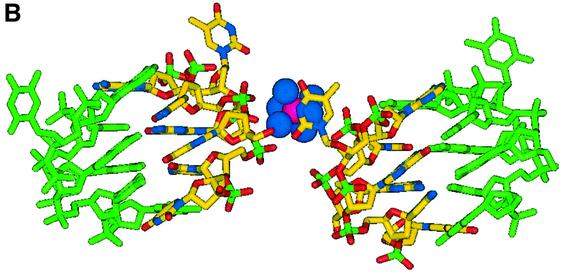

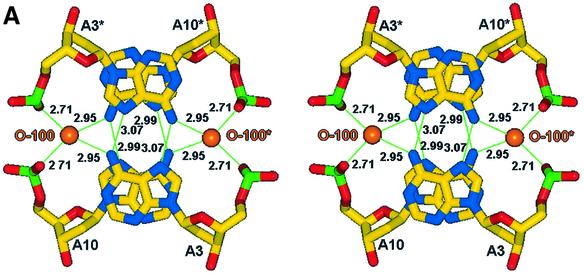

The asymmetric unit of the crystal structure comprises two juxtaposed single strands of d(GCATGCT) each of which fold to form a single stranded loop, the gross structural features of which closely resemble the motif found by Hunter et al. (24). The novel feature seen here, alongside the increased detail visible due to the use of highly redundant atomic resolution data, is a single cobalt hexammine site stabilising the lattice (Fig. 2A and B), where previously magnesium ions have been observed (24). The ‘biological unit’ for the heptamer sequence d(GCATGCT) consists of two complementary DNA loops related through 2-fold symmetry, generating a double stranded thymine looped quadruplex and two over-hanging thymine bases (Fig. 2A and B). The internal structure is stabilised with intra-strand G(N2)–C(O2) H-bonds between the residues C9–G12, G8–C13, C2–G5 and G1–C6. Inter-strand Watson– Crick pairings between the cytosine and guanine residues C9–G12*, G8–C13*, G12–C9*, C13–G8* and G1–C6*, C2–G5*, G5–C2*, C6–G1*, build up the pairs of stacking quadruplexes (Fig. 3). The quadruplex structure observed does not however exhibit the coplanar geometry more regularly associated with guanine tetrads. Instead the G/C pairs cross at an angle between 25 and 30° allowing for a more effective packing of the phosphate backbone for such a tightly looped structure. This feature is further aided by the single intra-strand G(N2)–C(O2) H-bonds observed, providing the structure with a greater degree of rotational freedom, as opposed to the more highly constrained double links observed within guanine rich quadruplexes. Complementing the quadruplex structure is an inter-strand A10–A10*, A3–A3* base pairing (Fig. 4A), where each is observed to bind through two N6–N7 H-bonds in the same non-planar orientation observed within the quadruplex. Further, these adenine residues stack at the structural terminus with another pair of adenines in an opposing orientation such that A10 stacks on A3* and A3 onto A10*, as the loop structure folds back upon itself. The localised phosphates and base edges yield two small pockets filled with a single highly conserved water site, O-100, and the symmetry related O-100* in the biological unit, separated by a distance of 8.45 Å. These tether the structural termini through a tetrahedral array of H-bonds between A10(O2P), A3(O2P)*, A3(N6)* and A10(N6)* for the 0–100 solvent site and A10(O2P)*, A3(O2P), A3(N6) and A10(N6) for the 0–100* water site, yielding a highly symmetrical, fully stabilised adenine quartet.

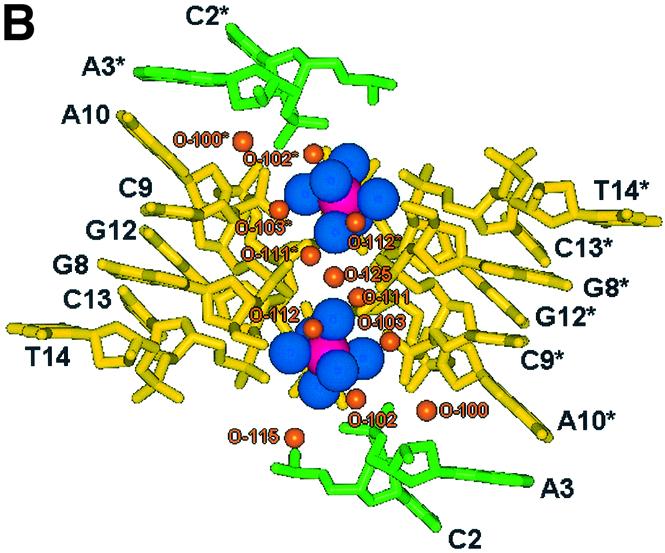

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic view of the crystallographic unit, illustrating the approximate cobalt hexammine site and the symmetry related residues, designated with a *. Strand one refers to bases G1–T7 and strand two to bases G8–T14. (B) View of the crystallographic unit, with symmetry related residues coloured green, all solvent positions have been removed for clarity.

Figure 3.

Sigma-A map for the quadruplex formed between the residues C2, G5 and their symmetry related partners C2*, G5* to a resolution of 1.1 Å. All bond distances are shown in angstroms. For the Sigma-A map 1σ is blue and 3σ is pink.

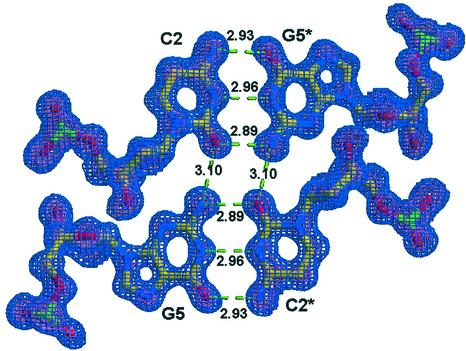

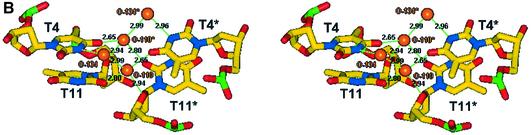

Figure 4.

(A) Stereo view of the packing adenine quartet, illustrating all bonding distances in angstroms and a conserved solvent site in orange. (B) Stereo view of the thymine loop residues T4 and T11 and their stacking and water mediated interactions between biological units. All bond distances are in angstroms and solvent sites are coloured orange.

The looped conformation is achieved for the biological unit through the central thymine residues T4, T4* and T11, T11* forming a single base loop at the pinnacle of each single strand, at near right angles to the adenine (A10/A3) plane. These residues stack with an adjacent thymine within the lattice, yielding four stacking thymine residues, T11/T4* and T4/T11* (Fig. 4B). Further to this stacking the thymines are stabilised through highly ordered solvent sites, O-110 that tetrahedrally tethers T11(O2), T4(O4)*, T11(O4′)* and through O-134, which binds to T4(N3)* and G8(O5)*, in the expected tetrahedral geometry. The symmetry related stabilisations are also observed for O-110*.

At the opposing end of the loop for the biological unit the terminal thymine residues T7/T7* and T14/T14* form a base overhang, forcing the helices to stack away from each other. The residues show a lack of base contacts and stack at the end of the helix to a cytosine, T7/C6* and T14/C13*. The packing is however strengthened through the interaction of T14(O3′) with T7(O2P)* at a distance of 2.50 Å and T14(O2P) with T7(O3′)* at a distance of 3.23 Å, and the same interactions are observed for T7 to T14*.

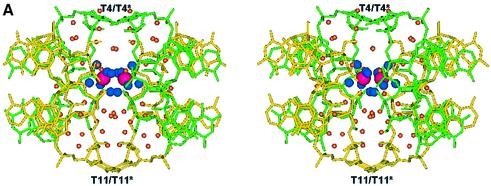

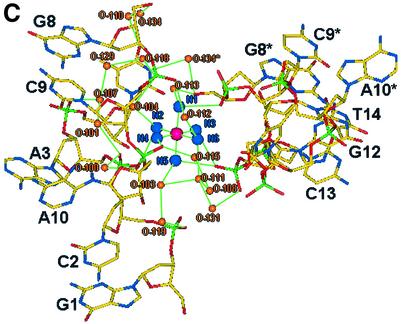

Further stabilising the structure we observe a cobalt hexammine residue, which binds in a solvent channel between the nucleotide strands, where a highly ordered array of water structure is built up between structural units. A channel of solvent ∼18 Å long, with a cobalt residue either side at a distance of 8.16 Å is filled with 56 water sites (Fig. 5A). This channel is enclosed at either end by the flipped out thymine residues, T4/T4* at one end and T11/T11* at the other. It is this highly ordered ion and solvent structure that stabilises the looped structure. However, the location of the cobalt ion relative to each symmetry related biological unit differs (Fig. 5B), with a greater number of direct H-bond interactions with strand 2, C9(O1P)–NCO(N1) of 2.99 Å, C13(O1P)–NCO(N3) of 2.95 Å and C13(O1P)–NCO(N5) of 3.02 Å, than strand 1, A3(O1P)–NCO(N2) of 3.06 Å. Numerous solvent mediated bridges complete the stabilisation of the closely packed strands leading to a highly structured solvent network (Fig. 5C). The cobalt hexammine residue therefore binds discretely, tethering the ends of one loop through C9 and C13* and bridging the adenine quartet through A3* and A10, therefore linking three strands within the unit cell.

Figure 5.

(A) Stereo view along the y-axis showing the channel of hydration spanning four strands of DNA enclosed by T4/T4* and T11/T11*. The figure also illustrates the two cobalt hexammine residues bound at its centre. Cobalts are pink, amines blue, waters orange, strand 1 is green and strand 2 yellow. (B) View of the localised cobalt hexammine residues and their locality to each DNA loop strand, illustrating strand 1 (green, G1–T7) to exhibit less contacts than strand 2 (yellow, G8–T14). (C) View of the hydration pattern surrounding the cobalt hexammine residue, illustrating its role in the ordering of the solvent structure and stabilisation of the DNA. Cobalts are pink, amines are blue and waters are orange.

For the hepta-nucleotide sequence d(GCATGCT), reported by Hunter et al. to a resolution of 1.8 Å, the structure is stabilised through the presence of a magnesium ion at a 2-fold symmetry axis where it directly bridges the helices at residues C2(O1P) and C6(O1P). This yields a more symmetrical packing array with an asymmetric unit comprising a single strand of DNA with an approximately halved c-axial length. These results have shown the ability of cobalt hexammine to stabilise this unusual structural loop in a similar fashion, lowering the crystallographic symmetry with little perturbation from the original model. The increased size of the stabilising ion has however forced a change within the lattice to create the alternative binding site observed, although the overall packing of the DNA loops is of a remarkably similar nature with an r.m.s. deviation of only 0.582 and 0.302 Å for strands one and two respectively when compared with the original search model (24).

DISCUSSION

The non-Watson–Crick base pairing of DNA is increasingly observed in structural biology, providing DNA targets of potential therapeutic value. Although the DNA sequence described here has no current biological relevance it does indicate that we must not simply apply the double helical B-DNA structure to modern biological problems and instead view DNA as the highly polymorphic system it is. The ability of certain DNA sequences to spontaneously form unexpected structural features is well documented with the DNA Holliday junction a good example (36). Decamer sequences were known to stack in a manner closely related to the Holliday crossover for some time (37), but it was not until the discovery of the required central ACC core (38) that a crystallographic junction was observed (39,40). The increasing amount of structural data solved to atomic or near atomic resolution is allowing for a better understanding of the fine structure and flexibility of DNA, which is unfortunately generally undecipherable within lower resolution studies. It is this increment in data and model quality that will allow us to improve our predictive knowledge of DNA and its interactions in the quest to discover new and improved therapeutic agents.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge access to the EMBL Hamburg synchrotron facility at DESY supported by the TMR/LSF and HPRI programmes of the European Union. For financial support we thank the University of Reading (to J.H.T. and S.C.M.T.), the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (to S.C.M.T.) and the Association for International Cancer Research (to B.C.G.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Watson D.J. and Crick,F.H.C. (1953) A structure of deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature, 171, 737–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kielkopf C.L., Ding,S., Kuhn,P. and Rees,D.C. (2000) Conformational flexibility of B-DNA at 0.74 Å resolution: d(CCAGTACTGG)2. J. Mol. Biol., 296, 787–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuerman G.S. and Van Meervelt,L. (2000) Conformational flexibility of the DNA backbone. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 122, 232–240. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suhnel J. (2001) Beyond nucleic acid base pairs: from triads to heptads. Biopolymers, 61, 32–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunn C.M. and Neidle,S. (1996) The high resolution crystal structure of the DNA decamer d(AGGCATGCCT). J. Mol. Biol., 256, 340–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kettani A., Basu,G., Gorin,A., Majumdar,A., Skripkin,E. and Patel,D.J. (2000) A Two-stranded template-based approach to G (C-A) triad formation: designing novel structural elements into an existing DNA framework. J. Mol. Biol., 301, 129–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neidle S. (2002) Nucleic Acid Structure and Recognition. Oxford University Press, New York.

- 8.Keniry M.A. (2000) Quadruplex structures in nucleic acids. Biopolymers, 56, 123–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haider S., Parkinson,G.N. and Neidle,S. (2002) Crystal structure of the potassium form of an Oxytricha nova G-quadruplex. J. Mol. Biol., 320, 189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harper A., Brannigan,J.A., Buck,M., Hewitt,L., Lewis,R.J., Moore,M.H. and Schneider,B. (1998) Structure of d(TGCGCA)2 and a comparison with other DNA hexamers. Acta Cryst., D54, 1273–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuryavyi V., Majumdar,A., Shallop,A., Chernichenko,N., Skripkin,E., Jones,R. and Patel,D.J. (2001) A double chain reversal loop and two diagonal loops define the architecture of a unimolecular DNA quadruplex containing a pair of stacked G(syn) G(syn) G(anti) G(anti) tetrads flanked by a G (T-T) triad and a T T T triple. J. Mol. Biol., 310, 181–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren J., Qu,X., Trent,J.O. and Chaires,J.B. (2002) Tiny telomere DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 2307–2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng J., Xiong,Y. and Sundaralingam,M. (2001) X-ray analysis of an RNA tetraplex (UGGGGU)4 with divalent Sr2+ ions at subatomic resolution (0.61Å). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 13665–13670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyoshi D., Nakao,A., Toda,T. and Sugimoto,N. (2001) Effect of divalent cations on antiparallel G-quartet structure of d(G4T4G4). FEBS Lett., 496, 128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spackova N., Berger,I. and Sponer,J. (2001) Structural dynamics and cation interactions of DNA quadruplex molecules containing mixed guanine/cytosine quartets revealed by large-scale MD simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 123, 3295–3307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parkinson G.N., Lee,M.P.H. and Neidle,S. (2002) Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Nature, 417, 876–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horvath P. and Schultz,S.C. (2001) DNA G-quartets in a 1.86 Å resolution structure of an Oxytricha nova telomeric protein-DNA complex. J. Mol. Biol., 310, 367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanaori K., Shibayama,N., Gohda,K., Tajima,K. and Makino,K. (2001) Multiple four-stranded conformations of human telomere sequence d(CCCTAA) in solution. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 831–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neidle S. and Read,M.A. (2000) G-Quadruplexes as therapeutic targets. Biopolymers, 56, 195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Read M.A. and Neidle,S. (2000) Structural characterization of a guanine-quadruplex ligand complex. Biochemistry, 39, 13422–13432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun D. and Hurley,L.H. (2001) Targetting telomeres and telomerase. Methods Enzymology. Academic Press, New York, Vol. 340, pp. 573–592. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Shafer R.H. and Smirnov,I. (2000) Biological aspects of DNA/RNA quadruplexes. Biopolymers, 56, 209–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koeppel F., Riou,J., Laoui,A., Mailliet,P., Arimondo,P.B., Labit,D., Petitgenet,O., Helene,C. and Mergny,J. (2001) Ethidium derivatives bind to G-quartets, inhibit telomerase and act as fluorescent probes for quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 1087–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonard G.A., Zhang,S., Peterson,M.R., Harrop,S.J., Helliwell,J.R., Cruse,W.B.T., Langlois d’Estaintot,B., Kennard,O., Brown,T. and Hunter,W.N. (1995) Self-association of a DNA loop creates a quadruplex: crystal structure of d(GCATGCT) at 1.8 Å resolution. Structure, 3, 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kettani A., Kumar,R.A. and Patel,D.J. (1995) Solution structure of a DNA quadruplex containing the fragile X syndrome triplet repeat. J. Mol. Biol., 254, 638–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang N., Gorin,A., Majumdar,A., Kettani,A., Chernichenko,N., Skripkin,E. and Patel,D.J. (2001) Dimeric DNA quadruplex containing major groove aligned A T A T and G C G C tetrads stabilized by inter-subunit Watson–Crick A T and G C pairs. J. Mol. Biol., 312, 1073–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thorpe J.H., Hobbs,J.R., Todd,A.K., Adams,A., Wakelin,L.P.G., Denny,W.A. and Cardin,C.J. (2000) Guanine specific binding at a DNA junction formed by d(CG(5BrU)ACG)2 with a Topoisomerase poison in the presence of Co2+ ions. Biochemistry, 39, 15055–15061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams A., Guss,J.M., Collyer,C.A., Denny,W.A. and Wakelin,L.P.G. (2000) A novel form of intercalation involving four DNA duplexes in an acridine-4-carboxamide complex of d(CGTACG)2. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 4244–4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang X., Robinson,H., Gao,Y.-G. and Wang,A.H.-J. (2000) Binding of macrocyclic bisacridine and ametantrone to CGTACG involves similar unusual interacalation platforms. Biochemistry, 39, 10950–10957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salisbury S.A., Wilson,S.E., Powell,H.R., Kennard,O., Lubini,P., Sheldrick,G.M., Escaja,N., Alazzouzi,E., Grandas,A. and Pedroso,E. (1997) The bi-loop, a new general four stranded DNA motif. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 5515–5518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith P.J. and Jones,C.J. (1999) DNA Recombination and Repair. Oxford University Press, New York.

- 32.Kabsch W. (1993) Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J. Appl. Cryst., 26, 795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vagin A.A. and Teplyako,A. (2000) An approach to multi-copy search in molecular replacement. Acta Cryst., D56, 1622–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheldrick G.M. and Schneider,T.R. (1997) SHELXL: high-resolution Refinement. Methods Enzymol., 277, 319–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McRee D.E. (1999) Xtalview/Xfit—a versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J. Struct. Biol., 125, 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eichman B.F., Mooers,B.H.M., Alberti,M., Hearst,J.E. and Ho,P.S. (2001) The crystal structures of psoralen cross-linked DNAs: drug dependent formation of Holliday junctions. J. Mol. Biol., 308, 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood A.A., Nunn,C.M., Trent,J.O. and Neidle,S. (1997) Sequence-dependent crossed helix packing in the crystal structure of a B-DNA decamer yields a detailed model for the Holliday junction. J. Mol. Biol., 269, 827–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eichman B.F., Vargason,J.M., Mooers,B.H.M. and Ho,P.S. (2000) The Holliday junction in an inverted repeat DNA sequence: sequence effects on the structure of four-way junctions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 3971–3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thorpe J.H., Teixeira,S.C.M., Gale,B.C. and Cardin,C.J. (2002) Structural characterization of a new crystal form of the four-way Holliday junction formed by the DNA sequence d(CCGGTACCGG)2: sequence versus lattice? Acta Cryst., D58, 567–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ortiz-Lombardia M., Gonzalez,A., Eritja,R., Aymami,J., Azorin,F. and Coll,M. (1999) Crystal structure of a DNA Holliday junction. Nat. Struct. Biol., 6, 913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]