Abstract

The deamination of nucleobases in DNA occurs by a variety of mechanisms and results in the formation of hypoxanthine from adenine, uracil from cytosine, and xanthine and oxanine from guanine. 2′-Deoxyxanthosine (dX) has been assumed to be an unstable lesion in cells, yet no study has been performed under biological conditions. We now report that dX is a relatively stable lesion at pH 7, 37°C and 110 mM ionic strength, with a half-life (t1/2) of 2.4 years in double-stranded DNA. The stability of dX as a 2′-deoxynucleoside (t1/2 = 3.7 min at pH 2; 1104 h at pH 6) was increased substantially upon incorporation into a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide, in which the half-life of dX at different pH values was found to range from 7.7 h at pH 2 to 17 700 h at pH 7. Incorporation of dX into a double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide resulted in a statistically insignificant increase in the half-life to 20 900 h at pH 7. Data for the pH dependence of the stability of dX in single-stranded DNA were used to determine the rate constants for the acid-catalyzed (2.6 × 10–5 s–1) and pH-independent (1.4 × 10–8 s–1) depurination reactions for dX as well as the dissociation constant for the N7 position of dX (6.1 × 10–4 M). We conclude that dX is a relatively stable lesion that could play a role in deamination-induced mutagenesis.

INTRODUCTION

The deamination of nucleobases in DNA can occur by simple hydrolysis, by the action of deaminase enzymes (1–3) or by reactions with endogenous genotoxins, most notably nitric oxide (4–6). Among the products of nucleobase deamination, 2′-deoxyxanthosine (dX) has received the least attention in terms of DNA repair in part due to the assumption that it is unstable and undergoes rapid depurination (7,8). We now report the results of studies aimed at defining the stability of dX under biological conditions.

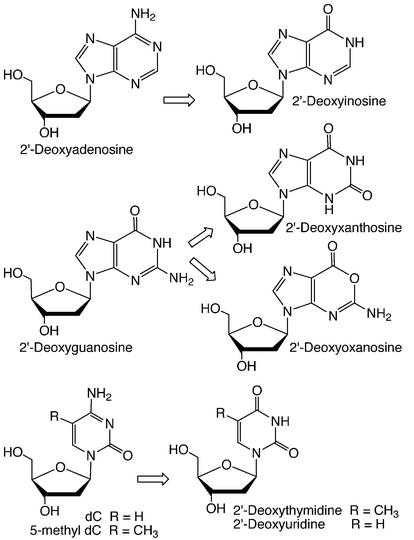

All mechanisms of nucleobase deamination result in the formation of xanthine (dX as a 2′-deoxynucleoside) from guanine, hypoxanthine (2′-deoxyinosine, dI) from adenine, uracil (2′-deoxyuridine, dU) from cytosine, and thymine (2′-deoxythymidine) from 5-methylcytosine (Fig. 1). Addi tionally, the reaction of nitrous acid with guanine in vitro has been shown to partition to form both xanthine and oxanine (2′-deoxyoxanosine, dO) (8), though the biological relevance of dO has not been demonstrated. The propensity for hydrolytic deamination occurs in the order 5-methylcytosine > cytosine > adenine > guanine (9,10). The half-life of uracil formation from cytosine lies in the range of 102–103 years with an increase to 104–105 years in double-stranded DNA (11–13), while C5-methylation of cytosine increases the rate deamination by 2- to 20-fold (12,13).

Figure 1.

Nucleobase deamination products.

Nitrosative deamination of nucleobases represents another physiologically important mechanism. Among the many sources of nitric oxide (NO), macrophages activated as part of the inflammatory process generate NO at a rate of ∼6 pmol s–1 per 106 cells (14). The NO reacts rapidly with O2 to produce nitrous anhydride (N2O3), a potent nitrosating agent that causes deamination of aromatic amines by formation of an aryl diazonium ion (reviewed in 15). The reactivity of N2O3 with nucleobases is reversed relative to hydrolytic deamination, with xanthine formation proposed to occur at twice the rate of uracil (6) and hypoxanthine (16). In human lymphoblastoid TK6 cells exposed to NO, the levels of both xanthine and hypoxanthine increased ∼40-fold over untreated controls (16).

The deamination products of DNA bases have been implicated in the formation of mutations. Especially important is the high rate of G:C→A:T mutations at CpG sites containing 5′-methylcytosine (17), which may result from the deamination of 5-methylcytosine to thymine (18). The deamination of cytosine to uracil also produces G:C→A:T mutations possibly by base pairing of uracil with adenine (18,19). On the basis of in vitro studies (20,21), xanthine represents another possible source of G:C→A:T mutations. However, the assumption of rapid depurination of dX has led to the suggestion (6–8) that the G:C→A:T mutations arise by insertion of adenine opposite the resulting abasic site (22–24).

Recently, the Kow and Weiss groups (25,26) presented evidence that Escherichia coli endonuclease V efficiently repairs xanthine residues. We now couple this observation with the first direct determination of the stability of dX under biological conditions and we conclude that dX is a relatively stable lesion with a half-life of 2 years at 37°C and pH 7 in double-stranded DNA. These results support models in which dX plays a direct role in deamination-induced mutagenesis in cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All chemicals used in the synthesis of dX and its derivatives were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). [γ-32P]ATP was obtained from Perkin Elmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). Enzymes for 5′-end-labeling were obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). The dX-containing oligodeoxynucleotide and its complement (with dC opposite dX) were synthesized by DNAgency (Berwyn, PA) using dX phosphoramidite synthesized as described below.

Synthesis of dX

O6-p-nitrophenylethyl-protected dX was synthesized from dG according to the procedure of Eritja et al. (20) with 1H-NMR chemical shifts (D2O) identical to published values (20); ESI-MS, m/z 567 (MH+). The p-nitrophenylethyl-protecting group was removed using 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene as described by Eritja et al. (20). The resulting dX was purified by HPLC with a Haisil HL reversed-phase semi-preparative column (5 µm, C18; 250 × 10 mm) and a 0–20% acetonitrile gradient (1% increase per minute) in 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 7, at 3 ml/min. Under these conditions, dX had a retention time of 11.5 min compared with a retention time of 9.9 min for xanthine base. Purified dX: UV spectroscopy, 248 and 277 nm (λmax); ESI-MS, m/z 269 (MH+), 153 (MH+-2′-deoxyribose).

Synthesis of an oligodeoxynucleotide containing dX

The O6-p-nitrophenylethyl-protected dX was converted to the phosphoramidite by standard procedures (27). The product displayed the expected 31P-NMR chemical shifts of 149.8 and 150.1 p.p.m. The phosphoramidite was incorporated into a 30mer oligodeoxynucleotide (DNAgency, Inc.) with the following sequence: GACCGATCCTCTAGAYCGACC TGCAGGCAG, where Y is either dX or dG; the complementary strand paired the dX or dG with dC. The oligodeoxynucleotide was purified by denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (28). To establish the presence of dX, the purified oligodeoxynucleotide was subjected to digestion with nuclease P1 and the released nucleotides were characterized by reversed-phase HPLC (Agilent 1100; Phenomenex LUNA 5 µm, C18, 250 × 3 mm; coupled to an Agilent 5989B ESI-mass spectrometer). ESI-MS analysis (PE Sciex API365) of the intact oligodeoxynucleotide indicated a mass of 9204 (theoretical 9203) compared with a mass of 9203 for the same oligodeoxynucleotide with dG replacing dX (theoretical 9202).

HPLC analysis of the stability of dX

Aliquots of a solution of dX (200 µM) in 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, were diluted 20-fold into preheated (37 or 50°C) potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, varying pH) containing 10 µM 2′-deoxythymidine (internal standard). At various times, aliquots were removed and subjected to HPLC analysis for the disappearance of dX (and appearance of X), as described for the synthesis of dX except that an analytical (3 mm) HPLC column was employed. The first-order rate constants for depurination of dX were determined from the loss of parent dX as a function of time.

Electrophoretic analysis of the stability of dX in an oligodeoxynucleotide

Substrate oligodeoxynucleotides were prepared by 5′-32P-end-labeling of the dX-containing strand by standard procedures (28). The labeled strand (1 µM) was annealed to its complement (3 µM) in 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, by heating to 95°C for 3 min followed by slow cooling to ambient temperature. An aliquot of the duplex oligodeoxynucleotide solution (1 µl) was then added to potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 2–12, 100 µl) and the sample incubated at either 37 or 50°C. At various times, aliquots were removed from the solution, the pH was adjusted to 7.4 (with HCl or NaOH), and abasic sites arising from depurination of dX were cleaved by putrescine dihydrochloride (100 mM; 1 h, 37°C) (29,30). The reaction mixture was dried in vacuo, resuspended in 95% formamide/0.02% xylene cyanol/0.02% bromophenol blue, heated at 95°C for 30 s and immediately placed on ice. Each sample was then loaded onto a 20% polyacrylamide sequencing gel (7 M urea; 30 cm × 60 cm × 0.4 mm) run at 2000 V for 3 h. Bands corresponding to the parent oligodeoxynucleotide and the cleavage product derived from depurination of dX were quantified by phosphorimager analysis using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics); the location of the cleavage product was verified by comigration with a 32P-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide of the corresponding sequence and length. At pH 7.4, dX depurination in the oligodeoxynucleotide proved to be sufficiently slow (see Results) to permit the incubation with putrescine to cleave abasic sites. Control reactions revealed that putrescine did not affect the stability of the dX-containing oligodeoxynucleotide (data not shown). The first-order rate constants for depurination of dX in single- and double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides were determined from the decrease in the signal intensity of the parent oligodeoxynucleotide as a percentage of the total radioactivity present in the sequencing gel lane. The data were fit to equation 2 using Kaleidagraph version 3.52 (Synergy Software).

Melting temperature determination for duplex oligodeoxynucleotides

The melting temperatures for duplex oligodeoxynucleotides containing dX, dI and dG were determined using a Cary 100 Bio UV-visible spectrophotometer. Melting temperatures were determined in potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) using a duplex oligodeoxynucleotide concentration of 718 nM and the following parameters: 260 nm wavelength; 50–90°C temperature range; 5°C/min ramp; 1 data point per °C. Three separate experiments were performed for each oligodeoxynucleotide. Studies with the single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides did not reveal a melting temperature (data not shown), which is consistent with a lack of significant secondary structure in the individual strands.

RESULTS

Characterization of dX and the dX-containing oligodeoxynucleotide

We performed the studies of the stability of dX as a nucleoside and in an oligodeoxynucleotide using direct synthesis of dX and its derivatives. The alternative approach of in situ generation of nucleobase deamination products in an oligodeoxynucleotide by treatment with nitrous acid (8) runs the risk of contamination with dO, which is formed along with dX during deamination of dG (31), and obviates the presence of dG in one strand of the oligodeoxynucleotide. Given the presumed instability of dX, we were careful to rigorously characterize dX and its derivatives and the dX-containing oligodeoxynucleotide to ensure proper structure and purity, with emphasis on the presence of abasic sites due to dX depurination. The protection strategy used for the synthesis of dX ensures that the phosphoramidite is incorporated into the oligodeoxynucleotide in the correct orientation and that the base does not undergo depurination during phosphoramidite synthesis (20). At each step of the synthesis of the 2′-deoxynucleoside and oligodeoxynucleotide, we verified product structure by NMR, ESI-MS and HPLC. Analysis of nuclease digestion products by LC/ESI-MS (positive ion mode) revealed a species that migrated with standard dX and yielded the expected ions at m/z 269 (MH+) and 153 (MH+-2′-deoxyribose). Finally, the position of the dX was confirmed by comparing the reaction of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum T/G mismatch DNA glycosylase (Trevigen, Inc.) (32) with duplex oligodeoxynucleotides containing either dX or dG opposite dT. The enzyme was able to cleave thymine of the T:G mismatch construct but not the T:X mismatch (data not shown).

Stability of dX

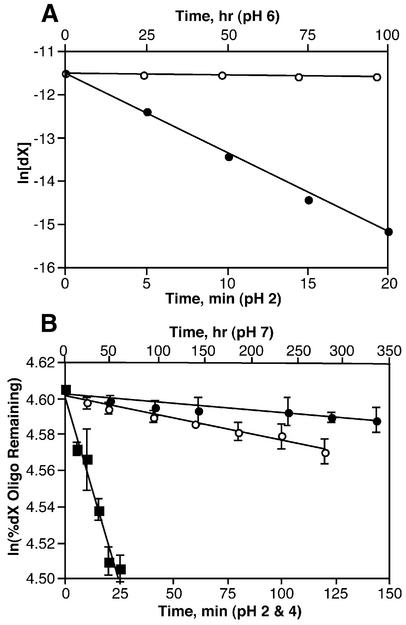

The kinetics of depurination of dX as a 2′-deoxyribonucleoside were determined by HPLC as loss of parent dX (and the appearance of X). Studies in oligodeoxynucleotides were performed by sequencing gel resolution of DNA fragments arising from depurination of dX in the 32P-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide, as shown in Figure 2 for the example at pH 2. Examples of the kinetics of dX depurination are shown in the graphs in Figure 3 and the rate constants are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Example of the sequencing gel analysis of dX depurination in a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide. Following incubation at 37°C and pH 2, the pH was adjusted to 7 and abasic sites cleaved with putrescine. Depurination at dX is indicated by the formation of a 15mer fragment. The small amount of cleavage product in the t = 0 lane was present in all samples and represents a cumulative background of dX depurination that arises during oligodeoxynucleotide synthesis and sample processing.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of dX depurination at 37°C. (A) 2′-Deoxyribonucleoside at pH 2 (closed circles) and pH 6 (open circles); data points represent mean ± SD (error bars smaller than symbol size) for three experiments. (B) Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide at pH 2 (squares), pH 4 (open circles) and pH 7 (closed circles); values represent mean ± SD for three to four experiments.

Table 1. Observed rate constants (s–1) for the depurination of dX as a 2′-deoxyribonucleoside and in single- and double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides as a function of pH and temperaturea.

| 37°C | 50°C | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | dX | Single | Double | Single | Double | |

| 2 | 3.2 (±0.1) × 10–3 | 2.5 (±0.2) × 10–5b | ||||

| 4 | 3.8 (±1.0) × 10–6b | |||||

| 6 | 1.7 (±0.1) × 10–7 | 3.7 (±1.2) × 10–8b | 4.3 × 10–4c | |||

| 7 | 1.1 (±0.3) × 10–8 | 9.2 (±3.4) × 10–9 | 8 × 10–5c | 8.3 × 10–5c | ||

| 8 | 1.8 (±0.3) × 10–8b | 8.3 × 10–5c | ||||

| 10 | 1.3 (±0.1) × 10–8 | |||||

| 12 | 1.3 (±0.3) × 10–8 |

aRate constants (s–1) were derived from four independent experiments, with data representing mean (± SD). dX, 2′-deoxyxanthosine; single and double, single- and double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide, respectively.

bSignificantly different from pH 7, P < 0.05 for Student’s t-test.

cResults from a single experiment.

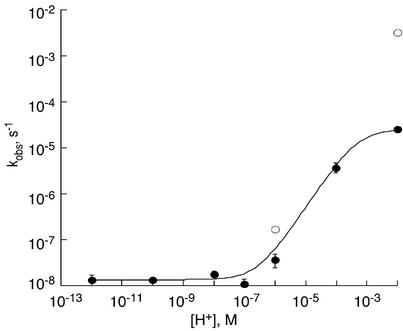

As expected, the 2′-deoxyribonucleoside form of dX underwent depurination at a higher rate under acidic conditions, with a half-life at 37°C of 2 × 102 s at pH 2 (kobs = 3.2 × 10–3 s–1) and 4 × 106 s at pH 6 (kobs = 1.7 × 10–7 s–1). These rates are considerably faster than those determined for single- and double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides under conditions of varying pH and temperature, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 1. There is a decrease in the rate of depurination as pH is elevated, reaching what amounts to a plateau at pH 7 and above, as depicted in Figure 4. At neutral and alkaline pH, there is variation in the experimental values due to the errors inherent in measuring small changes in the quantities of cleavage product. However, it is clear from Figure 4 that there is at least a three order-of-magnitude stabilization of dX as the pH is raised from 2 to 7.

Figure 4.

Plot of the dX depurination rate constants at 37°C versus [H+] in a single-strand oligodeoxynucleotide (closed circles) and as a 2′-deoxynucleoside (open circles). Error bars indicate standard deviation for three to five experiments; the error bars are smaller than symbol size in some cases. The curve was generated from equation 2, as described in the text, using the single-strand oligodeoxynucleotide data; r = 0.998; χ2 = 1.6 × 10–12.

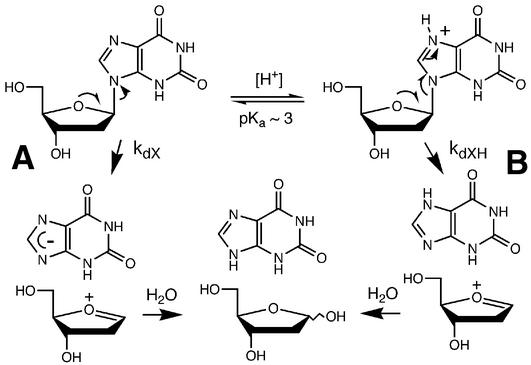

The data for the pH dependence of dX depurination permitted estimation of the acid dissociation constant for the N7 of dX and the rate constant for the acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of dX. By analogy to the generally established depurination of dG (33–38), depurination of dX appears to occur by two mechanisms depending on the pH, as shown in Scheme 1. At low pH (<6), there is a rapid protonation of N7 followed by a rate-limiting cleavage of the N-glycosidic bond and rapid addition of water to the C1 position of the cationic abasic site. At pH ≥ 7, the depurination rate becomes independent of pH due to a slower, rate-limiting direct cleavage of the N-glycosidic bond followed by rapid protonation of the anionic base and addition of water to the cationic sugar residue. The following rate equation thus applies to these processes:

Scheme 1. Proposed mechanisms of dX depurination.

d[X] / dt = kdX · [dX] + kdXH · [dXH]1

where X is depurinated xanthine base, kdX and kdXH are the rate constants for the two depurination pathways depicted in Scheme 1, and dXH is N7-protonated dX. It can be shown by appropriate substitution and integration of equation 1 that:

kobs = (kdXH · Ka–1 · [H+] + kdX) / (Ka–1 · [H+] + 1)2

where kobs is the apparent rate constant for depurination of dX, Ka is the acid dissociation constant for the N7 position of dX, and [H+] is the hydronium ion concentration. The value of the rate constant for pH-independent hydrolytic depurination of dX, kdX, can be derived from the limiting rate constant at pH > 7 (1.35 × 10–8 s–1; see Table 1). A reasonable initial value for kdXH is the rate constant determined at pH 2 (2.5 × 10–5 s–1). Due to the presence of the electron-withdrawing O2 in dX, the proton dissociation constant for the N7 position of dX is likely to be higher than that for dG (2.3) (39), so that the majority of dX will be protonated at pH 2 and the depurination rate constant thus a reasonable estimate of kdXH. Using values of Ka in the range of 10–2–10–3 M and kdXH in the range of 1–5 × 10–5 s–1 as initial estimates, we fitted the depurination data from Table 1 (single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide at 37°C) to equation 2 and a best fit was achieved for Ka = 6.1 × 10–4 M and kdXH = 2.6 × 10–5 s–1.

The data in Table 1 also demonstrate that, at both 37 and 50°C, there is little additional stabilization of dX afforded by conversion of single-stranded to double-stranded DNA (statistically insignificant 10–15% increase in the half-life of the dX-containing strand at pH 7). That the double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide retains its secondary structure at 50°C was confirmed by Tm studies. Under conditions identical to those employed in the dX stability studies, the following melting temperatures were determined for the duplex oligodeoxynucleotides containing dG, dI or dX: dG, 78.16 ± 0.26°C; dI, 74.16 ± 1.10°C; and dX, 73.26 ± 0.53°C. The 5°C decrease in the duplex stability caused by the change from a G:C base pair to X:C is consistent with previous observations (8,20).

Control reactions indicated that the putrescine treatment employed to cleave abasic sites resulting from depurination of dX in oligodeoxynucleotides (29,40) did not affect the stability of dX (data not shown). The small quantity of cleavage product apparent in the t = 0 lane in Figure 2 (3%) was present in all samples at all pHs and represents a cumulative background of dX depurination that arises during oligodeoxynucleotide synthesis and sample processing. This background cleavage was subtracted from the time course data. Depurination rate determinations at pH ≥ 6 required reaction times of up to 2 weeks, which amounts to one half-life for the 32P label on the oligodeoxynucleotide. In all cases, however, the quantity of cleavage product was determined relative to the total radioactivity present in the gel lane, so decay of the 32P did not affect the rate determinations.

DISCUSSION

The present studies were undertaken to define the stability of dX under biological conditions of temperature and pH. The only other study of dX stability, that reported by Suzuki et al. (8), was performed at pH 4 and 70°C and, without knowledge of the temperature and pH dependence of dX depurination, it is not possible to extrapolate the data to biological conditions. The results of our studies reveal that dX is a relatively stable 2′-deoxynucleoside under biological conditions of temperature and pH. At pH 7, 37°C and 110 mM ionic strength, dX in single-stranded DNA has a half-life of ∼2 years. The results also reveal novel insights into the chemistry of dX depurination.

The depurination rate constant for dX in a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide was found to be inversely proportional to [H+] at pH < 7 and independent of pH above 7 (Fig. 4). This behavior is entirely consistent with the observed pH dependence for depurination of dG and dA as 2′-deoxynucleosides and in DNA (33–38) and thus represents two depurination mechanisms: a specific acid-catalyzed (33) N-glycosidic bond cleavage of dX at pH < 7 and a pH-independent direct N-glycosidic bond cleavage at pH > 7 (Scheme 1). The studies revealed that the rate constant for the acid-catalyzed depurination of dX, kdXH = 2.6 × 10–5 s–1, is 2000-fold greater than the pH-independent hydrolysis of dX, kdX = 1.3 × 10–8 s–1. The latter value is ∼100-fold greater than the analogous rate constant of ∼10–10 s–1 for depurination of dG and dA in DNA at 37°C and pH 7 determined by Lindahl and Nyberg (38).

It was also observed that the incorporation of dX into single- and double-stranded DNA stabilizes it toward depurination. We observed a ∼5-fold stabilization of dX at pH 7 afforded by incorporation of the deoxynucleoside into single-strand oligodeoxynucleotide, which is considerably larger than the 1.1-fold effect observed by Suzuki et al. (8) at pH 4. The basis for this difference may lie in the different oligodeoxynucleotide substrates used for the two sets of studies. Suzuki et al. (8) used a 12mer oligodeoxynucleotide in which the dX residue was surrounded entirely by dT (d[T5XT6]), while we employed a 30mer oligodeoxynucleotide in which the dX was embedded in mixture of purines and pyrimidines (-AGAXCGA-). Given the strong (4–5-fold) sequence context effects for depurination of dG and dA (36), it is likely that the difference in dX depurination rates observed in our studies and those of Suzuki et al. (8) arise as a result of the different oligodeoxynucleotide sequences employed.

Regarding differences between single- and double-stranded DNA, there was a small (1.2–2-fold), but statistically insignificant, reduction in the rate of dX depurination in the double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide compared with the single-stranded form. This is less than the 3–4-fold reduction in depurination of dG and dA in the analogous structural transition in DNA observed by Lindahl and Nyberg (38), though some caution must be exercised in the interpretation of our results given the relatively large error incurred in the determination of depurination rates at pH 7 (Table 1). Though speculative in the absence of NMR data, one possible explanation for the lack of a stabilizing effect in double-stranded DNA involves a dX-induced disruption of local DNA structure, such as aberrant or weak H-bonding. Such helical destabilization is supported by our observation of a 5°C decrease in the melting temperature of the duplex oligodeoxynucleotide stability containing dX. The source of the helical destabilization may be related to the relatively low pKa for the N3 of dX (∼5.6 for the 2′-deoxynucleoside) (41), which would result in a fair degree of negative charge on the xanthine bases at pH 7. However, is likely that the N3 pKa is affected by H-bonding in the double-stranded structure, as observed in other studies (42,43).

The stability of dX may play a role in the mutagenicity of base deamination products. If dX were an unstable species, then depurination would occur prior to DNA replication and any resulting mutations, apart from those induced during repair synthesis, would result from the abasic site. However, we have demonstrated that dX is relatively stable in DNA with a half-life of 2 years. At this rate, endogenously formed dX residues, if not repaired, can be expected to undergo depurination to the extent of 3 and 11% in 1 and 4 months, respectively. Given the relatively slow rate of cell division in tissues such as the human colon (three divisions per year) (44), the bulk of dX residues present in a cell will be present during cell replication and may thus contribute to mutagenesis. This hypothesis is supported by several studies. In repair-deficient E.coli exposed to nitrous acid, an agent that causes nucleobase deamination (25), the G:C→T:A mutations expected for a preponderance of apurinic sites at presumably unstable dX residues (22) represented only 0.2% of the mutations. The bulk of the mutations consisted of G:C→A:T and A:T→G:C transitions (25). While the G:C→A:T mutations could arise by deamination of dC or 5-methyl-dC, dX has been shown to cause G:C→A:T mutations in vitro (20). Consistent with these studies is the increase in nitrous acid-induced G:C→A:T mutations in E.coli lacking endonuclease V (25), an enzyme that has been shown by He et al. (26) to repair dX with high efficiency. It is thus likely that dX contributes to the burden of mutagenic lesions in a cell.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Xinfeng Zhou for helpful discussions about the depurination kinetics and to acknowledge financial support from grant CA26735-20 from the National Cancer Institute and grant ES02109-24 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anant S. and Davidson,N.O. (2001) Molecular mechanisms of apolipoprotein B mRNA editing. Curr. Opin. Lipidol., 12, 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs H. and Bross,L. (2001) Towards an understanding of somatic hypermutation. Curr. Opin. Immunol., 13, 208–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maas S. and Rich,A. (2000) Changing genetic information through RNA editing. Bioessays, 22, 790–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park M. and Loeppky,R.N. (2000) In vitro DNA deamination by alpha-nitrosaminoaldehydes determined by GC/MS-SIM quantitation. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 13, 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fix D.F., Koehler,D.R. and Glickman,B.W. (1990) Uracil-DNA glycosylase activity affects the mutagenicity of ethyl methanesulfonate: evidence for an alternative pathway of alkylation mutagenesis. Mutat. Res., 244, 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caulfield J.L., Wishnok,J.S. and Tannenbaum,S.R. (1998) Nitric oxide-induced deamination of cytosine and guanine in deoxynucleosides and oligonucleotides. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 12689–12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindahl T. (1993) Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature, 362, 709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki T., Matsumura,Y., Ide,H., Kanaori,K., Tajima,K. and Makino,K. (1997) Deglycosylation susceptibility and base-pairing stability of 2′-deoxyoxanosine in oligodeoxynucleotide. Biochemistry, 36, 8013–8019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindahl T. and Nyberg,B. (1974) Heat-induced deamination of cytosine residues in deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry, 13, 3405–3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro R. and Klein,R.S. (1966) The deamination of cytidine and cytosine by acidic buffer solutions. Mutagenic implications. Biochemistry, 5, 2358–2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frederico L.A., Kunkel,T.A. and Shaw,B.R. (1990) A sensitive genetic assay for the detection of cytosine deamination: determination of rate constants and the activation energy. Biochemistry, 29, 2532–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X. and Mathews,C.K. (1994) Effect of DNA cytosine methylation upon deamination-induced mutagenesis in a natural target sequence in duplex DNA. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 7066–7069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen J.-C., Rideout,W.M.,III and Jones,P.A. (1994) The rate of hydrolytic deamination of 5-methylcytosine in double-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 972–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis R.S., Tamir,S., Tannenbaum,S.R. and Deen,W.M. (1995) Kinetic analysis of the fate of nitric oxide synthesized by macrophages in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 29350–29355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer B. and Grunberger,D. (1983) Molecular Biology of Mutagens and Carcinogens. Plenum, New York.

- 16.Nguyen T., Brunson,D., Crespi,C.L., Penman,B.W., Wishnok,J.S. and Tannenbaum,S.R. (1992) DNA damage and mutation in human cells exposed to nitric oxide in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 3030–3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncan B.K. and Weiss,B. (1978) In Hanawalt,P.C., Errol,C., Friedberg,E.C. and Fox,F. (eds), DNA Repair Mechanisms. Academic Press, New York, pp. 183–186.

- 18.Coulondre C., Miller,J.H., Farabaugh,P.J. and Gilbert,W. (1978) Molecular basis of base substitution hotspots in Escherichia coli. Nature, 274, 775–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duncan B.K. and Miller,J.H. (1980) Mutagenic deamination of cytosine residues in DNA. Nature, 287, 560–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eritja R., Horowitz,D.M., Walker,P.A., Ziehler-Martin,J.P., Boosalis,M.S., Goodman,M.F., Itakura,K. and Kaplan,B.E. (1986) Synthesis and properties of oligonucleotides containing 2′-deoxynebularine and 2′-deoxyxanthosine. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 8135–8153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamiya H., Miura,H., Suzuki,M., Murata,N., Ishikawa,H., Shimizu,M., Komatsu,Y., Murata,T., Sasaki,T., Inoue,H. et al. (1992) Mutations induced by DNA lesions in hot spots of the c-Ha-ras gene. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser., 179–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loeb L.A. and Preston,B.D. (1986) Mutagenesis by apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. Annu. Rev. Genet., 20, 201–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boiteux S. and Laval,J. (1982) Coding properties of poly(deoxycytidylic acid) templates containing uracil or apyrimidinic sites: in vitro modulation of mutagenesis by deoxyribonucleic acid repair enzymes. Biochemistry, 21, 6746–6751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strauss B., Rabkin,S., Sagher,D. and Moore,P. (1982) The role of DNA polymerase in base substitution mutagenesis on non-instructional templates. Biochimie, 64, 829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schouten K.A. and Weiss,B. (1999) Endonuclease V protects Escherichia coli against specific mutations caused by nitrous acid. Mutat. Res., 435, 245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He B., Qing,H. and Kow,Y.W. (2000) Deoxyxanthosine in DNA is repaired by Escherichia coli endonuclease V. Mutat. Res., 459, 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beaucage S.L., Bergstrom,D.E., Glick,G.D. and Jones,R.A. (2000) Current Protocols in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- 28.Ausubel F.M., Brent,R., Kingston,R.E., Moore,D.D., Seidman,J.G., Smith,J.A. and Struhl,K. (1989) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- 29.Lindahl T. and Andersson,A. (1972) Rate of chain breakage at apurinic sites in double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry, 11, 3618–3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu L., Golik,J., Harrison,R. and Dedon,P. (1994) The deoxyfucose-anthranilate of esperamicin A1 confers intercalative DNA binding and causes a switch in the chemistry of bistranded DNA lesions. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 116, 9733–9738. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki T., Kanaori,K., Tajima,K. and Makino,K. (1997) Mechanism and intermediate for formation of 2′-deoxyoxanosine. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser., 313–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horst J.P. and Fritz,H.J. (1996) Counteracting the mutagenic effect of hydrolytic deamination of DNA 5-methylcytosine residues at high temperature: DNA mismatch N-glycosylase Mig.Mth of the thermophilic archaeon Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum THF. EMBO J., 15, 5459–5469. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zoltewicz J.A., Clark,D.F., Sharpless,T.W. and Grahe,G. (1970) Kinetics and mechanism of the acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of some purine nucleosides. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 92, 1741–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venner H. (1966) Research on nucleic acids. XII. Stability of the N-glycoside bond of nucleotides. Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem., 344, 189–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapiro R. and Danzig,M. (1972) Acidic hydrolysis of deoxycytidine and deoxyuridine derivatives. The general mechanism of deoxyribonucleoside hydrolysis. Biochemistry, 11, 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki T., Ohsumi,S. and Makino,K. (1994) Mechanistic studies on depurination and apurinic site chain breakage in oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 4997–5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bender M.L. (1971) Mechanisms of Homogeneous Catalysis from Protons to Proteins. Wiley-Interscience, New York.

- 38.Lindahl T. and Nyberg,B. (1972) Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry, 11, 3610–3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Acharya P., Trifonova,A., Thibaudeau,C., Foldesi,A. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1999) The transmission of the electronic character of guanin-9-yl drives the sugar-phosphate backbone torsions in guanosine 3′,5′-bisphosphate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 38, 3645–3650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dedon P.C., Salzberg,A.A. and Xu,J. (1993) Exclusive production of bistranded DNA damage by calicheamicin. Biochemistry, 32, 3617–3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roy K.B. and Miles,H.T. (1983) Tautomerism and ionization of xanthosine. Nucl. Nucl., 2, 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheppard T.L., Ordoukhanian,P. and Joyce,G.F. (2000) A DNA enzyme with N-glycosylase activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 7802–7807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Legault P. and Pardi,A. (1997) Unusual dynamics and pka shift at the active site of a lead-dependent ribozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 119, 6621–6628. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herrero-Jimenez P., Tomita-Mitchell,A., Furth,E.E., Morgenthaler,S. and Thilly,W.G. (2000) Population risk and physiological rate parameters for colon cancer. The union of an explicit model for carcinogenesis with the public health records of the United States. Mutat. Res., 447, 73–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]