Abstract

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality submitted the first annual National Healthcare Disparities Report to Congress in December, 2003. This first report will provide a snapshot of the state of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in access and quality of care in America. It examines disparities in the general population and within the Agency's priority populations. While focused on extant data, the first report will form the foundation for future versions, which examines causes of disparities and shape solutions to the problem. As patient advocates and agents of change, primary care physicians play a critical role in efforts to eliminate disparities in health care. Continuing participation by primary care physicians in the development and refinement of the National Healthcare Disparities Report is essential.

Keywords: disparities, health care, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status

The 2002 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare (Unequal Treatment) extensively documents health care disparities in the US by race and ethnicity.1 The IOM's examination finds that disparities in health care are substantial, even after accounting for characteristics typically associated with disparities, such as health insurance coverage and income. While the causes of these disparities are not well understood, a variety of individual, institutional, and health system factors likely contribute to their existence, and efforts toward reducing disparities will need to address health care inequities at each of these levels.

A vital step in this effort is the systematic collection and analysis of health care data to discern areas of greatest need, monitor trends over time, and identify and subsequently replicate model programs that are successful at addressing those needs. To that end, and as included in its 1999 reauthorization legislation, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has released the first annual National Healthcare Disparities Report (NHDR). A driving force behind the NHDR was, in part, the evolving evidence base on racial/ethnic disparities. In particular, the article by Schulman et al. on racial disparities related to cardiac catheterization captured the attention of Congress when it was released.2 The purpose of the NHDR is to document and track over time “prevailing disparities in health care delivery as they relate to racial factors and socioeconomic factors in priority populations.11 The release of the first NHDR will challenge primary care physicians to redouble their efforts to reduce disparities in health care. Many of the disparities discussed in the NHDR relate to preventive services and management of common chronic diseases typically delivered in primary care settings. In addition, the long-standing commitment and involvement of primary care physicians in activities that are essential to reduce disparities, such as quality improvement, cultural competency, and patient advocacy, place them in a unique position to lead the Nation's campaign to eliminate disparities.

WHY HAVE A NATIONAL HEALTHCARE DISPARITIES REPORT?

In its 1999 reauthorization legislation, Congress directed AHRQ to produce 2 new annual reports, the National Healthcare Disparities Report (NHDR) and the National Healthcare Quality Report (NHQR).3 These companion reports will include a broad set of performance measures that will monitor the Nation's progress toward improved health care delivery. Specifically, the NHQR will describe the quality of health care provided in the U.S., and the NHDR will document and track racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in care over time across rural, urban, and innercity areas and among the following priority populations: 1) low income groups; 2) racial and ethnic minorities; 3) women; 4) children; 5) the elderly; and 6) individuals with special health care needs, including individuals with disabilities and individuals who need chronic care or end-of-life care.

These health care disparities in access, cost, use, and quality of health care extend beyond differences in health status indicators such as morbidity or mortality rates. The NHDR will enable policy makers to evaluate, in the words of the reauthorization legislation, “the Nation's progress toward the elimination of health care disparities.” While not designed to measure the progress of any one specific program or policy, the data and analyses presented in the report provide a comprehensive source of information spanning a broad range of health care disparity issues.

DESIGNING THE REPORT

In an effort separate from its work on Unequal Treatment, the IOM has worked with AHRQ to develop the conceptual framework and structure of the NHDR in order to maximize its usefulness. With input from a wide variety of organizations, including public meetings and commissioned reports from experts in the field, the IOM built upon the conceptual framework it had previously prepared for the NHQR.4 Its recommendations for the NHDR were released in September 2002.5

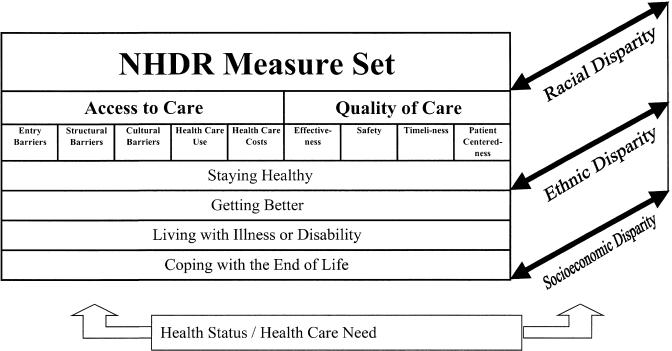

The NHQR's conceptual framework focuses on 2 dimensions of care: components of health care quality (including safety, effectiveness, patient centeredness, and timeliness) and consumer perspectives on health care needs (including staying healthy, getting better, living with illness or disability, and coping with the end of life). The NHDR conceptual framework, shown in Figure. 1, expands upon this in 3 ways. First, disparities in health care encompass far more than disparities in the quality of clinical encounters. In particular, difficulties gaining access to health care disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities and persons of lower SES. Hence, the NHDR framework adds measures of access to care, and these measures constitute about half of the NHDR measure set. Second, the NHDR adds a disparities dimension to the framework. This dimension is the focus of the NHDR, and the framework illustrates that all measures of access and quality of care will be examined for differences related to race, ethnicity, and SES. Finally, because disparities in health care need to be interpreted in the context of underlying disparities in health, this conceptual framework rests upon a representation of disparities in health status and health care need.

FIGURE 1.

NHDR conceptual framework.

SELECTING MEASURES

The first NHDR relies heavily on the quality measures that were developed for the NHQR. NHQR measures were developed through a process that included calls for measures to federal agencies and private sector organizations, recommendations from an IOM committee, and testimony sponsored by the National Committee for Vital and Health Statistics. Final measures were selected by an Interagency Work Group with representatives from throughout Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) on the basis of importance, scientific soundness, and feasibility.

Similar processes were used to develop the access measures for the first NHDR. While numerous organizations have worked to develop consensus measures of quality of care, parallel activities to achieve consensus around measures of access to care are generally lacking. A notable exception is Healthy People 2010 measures related to access to quality health services. However, these measures do not include the breadth of topics NHDR sought to address. As a result of these complexities, the NHDR solicited a broad range of input when developing the set of access measures to be included in the report. Input included responses to public calls for measures, recommendations from the IOM Committee on Guidance for Designing a NHDR, and testimony from a variety of stakeholders, including the American Medical Association, the American Association of Family Physicians, the American Association of Health Plans, the Washington Business Group on Health, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, and the National Association of City and County Health Officials. Final measures of access to care were selected by AHRQ and the Interagency Work Group for the NHDR with broad representation from the DHHS.

The final NHDR measure set includes approximately 300 measures across a range of topics (Table 1). The nearly 150 quality measures are identical to the measure set for the NHQR. Measures in the quality domain of effectiveness are further subdivided by specific conditions, including cancer, diabetes, heart disease, HIV disease, maternal and child health, mental health, respiratory diseases, and long-term care. There are approximately 150 access to care measures covering topics related to entry into the health care system, structural barriers within the system, cultural barriers to care, health care use, and health care costs. Entry barriers studied include lack of health insurance coverage and a usual source of care and unmet health care needs. Structural barriers include problems with transportation and provider availability. Cultural barriers include the quality of patient–provider relationships and communication and of health care information. Finally, health care utilization and costs encompass inpatient, emergency, ambulatory, specialty, mental health/substance abuse, HIV, dental, home health, and nursing home services, as well as prescription medications.

Table 1.

NHDR Measure Set: Major Topics

| Quality of health care |

| 1. Effectiveness |

| a.Cancer: cancer screening, late-stage diagnosis, cancer deaths, hospice care for cancer |

| b.Chronic kidney disease: dialysis care, renal transplantation |

| c.Diabetes: diabetic care, hospitalizations for diabetes and complications |

| d.Heart disease: screening and management of risk factors, inpatient treatment of acute myocardial infarction and acute heart failure |

| e.HIV/AIDS: new AIDS cases, HIV deaths |

| f.Maternal and child health: maternity care, childhood immunizations |

| g.Mental Health: suicide deaths |

| h.Respiratory diseases: immunizations for influenza and pneumococcal disease, inpatient treatment of pneumonia, hospitalizations for asthma |

| i. Nursing home and home health care: care in nursing homes |

| 2. Patient safety |

| a.Nosocomial infections |

| b.Complications of care |

| c.Injuries and adverse events |

| d.Birth-related trauma |

| e.Medication safety |

| 3. Timeliness |

| 4. Patient-centeredness |

| Access to health care |

| 1. Entry into the health care system |

| a.Health insurance coverage |

| b.Usual source of care |

| c.Patient perceptions of need |

| 2. Structural barriers within the health care system |

| a.Barriers to getting care |

| b.Waiting times |

| 3. Patient perceptions of provider's ability to address patient needs |

| a.Patient–provider communication |

| b.Patient–provider relationship |

| c.Cultural competency |

| d.Health information |

| 4. Health care utilization |

| a.Routine health care |

| b.Acute care |

| c.Chronic care |

| d.Avoidable hospitalizations |

| e.Mental health care and substance abuse treatment |

| f.HIV care |

| 5. Health care costs |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

SELECTING DATA

Once the measure set was developed, appropriate data sources for each measure were identified. These included federal data sets from AHRQ, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the Indian Health Service (IHS). When more than one data source was available, several criteria determined which data source was used: 1) The data source had to provide data by race/ethnicity and/or socioeconomic status; 2) Because the NHDR is a report on the status of disparities across the US, nationally representative databases were preferred; 3) If a measure is identical to one included in Healthy People 2010,6 the NHDR used the same database that provided information for that effort; 4) To maximize the information available concerning small populations, larger databases were preferred; and 5) To enable the tracking of trends over time, data which are collected periodically were emphasized over one-time efforts.

If no federal or nationally representative data sources were available for a measure, the NHDR relied on nonfederal and/or regional data sources. To address gaps in federal data collection related to cultural competency and health care information, we used data from the Commonwealth Fund 2001 Health Care Quality Survey. Gaps in available data on HIV are filled by data collected by the HIV Research Network. Finally, to allow more detailed examinations of Hispanic and Asian subgroups and of American Indians and Alaska Natives, the NHDR used data from the California Health Interview Survey.

In total, the NHDR integrated data from approximately 30 different data sources. The full measure set and associated data sources are available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr02/prenhdr.htm.

MEASURING DISPARITIES

The NHDR grappled with a number of issues related to measuring disparities. Should disparities be measured as absolute differences or relative ratios between 2 groups or as a summarized index of disparity?7 If measured between 2 groups, what is an appropriate reference group: the total population, a specific group, or the best-performing group? Can disparities related to underlying need be differentiated from those that are unrelated to need? In the absence of scientific consensus or of federal recommendations, the first NHDR reports differences as relative ratios, relative to the most numerous group: racial groups are compared with whites, ethnic groups are compared with non-Hispanic whites, income groups are compared with a high-income group (family income of 400% or more of federal poverty thresholds), education groups are compared with a high-education group (any college education). Measures account for underlying need when possible. For example, preventive care is assessed for populations of appropriate age and gender.

THE FIRST NATIONAL HEALTHCARE DISPARITIES REPORT

The primary goal of the first NHDR is to provide a national snapshot of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in health care in the general population and among AHRQ's priority populations. Achieving this goal required weighing conflicting needs and interests to present a balanced view of those areas of health care in which disparities do and do not exist. Providing an overview of a broad range of measures precludes in-depth examination of each one. For each measure, the report includes data on racial/ethnic disparities across each priority population, stratified by socioeconomic status (as recommended by the IOM), but does not include multivariate analyses or measures at the intersection of multiple priority populations (e.g., racial disparities among low-income women). In addition, the report emphasizes data at the national level rather than at the state or local levels. Ultimately, then, the first report favors a broader scope of measures over more detailed analysis of each measure. This approach was chosen to encourage users to examine patterns of disparity across groups of related measures rather than focus on individual measures.

It is hoped that the first NHDR will be useful to Congress and other national health care policy makers, state and local health care policy makers, health plans and providers, and patients. For national health policy makers, the first NHDR provides a national baseline from which to measure progress toward the goal of eliminating health care disparities. While disparities in health care are a national problem, solutions will need to be developed locally. The first NHDR provides state and local health policy makers with a general model for monitoring health care disparities that can be adapted for a variety of local conditions. For health plans and providers, the first NHDR provides flexible self-assessment tools that can be used to examine, compare, and improve the care they provide. For patients, the first NHDR provides a starting point for conversions with plans and providers to ensure that all receive care they need.

CHALLENGES

Geographic regions and types of practices differ in the specific disparities they face, highlighting the need to track disparities for different conditions, services, and populations. Hence, to maximize usability to a broad spectrum of stakeholders, the first NHDR does not propose a specific, narrow set of metrics and benchmarks for adoption by all policy makers, plans, and providers. Instead, it includes a broad set of measurement tools, from which users can select those most applicable to their locality or practice. However, a disadvantage of this broad approach is the large number of data sources used in the report, each with its unique strengths and weaknesses. For example, surveys have the advantage of allowing individuals to identify their own race and ethnicity; however, laypersons may not report details of health care accurately. Health care facility data have the advantage of standardized coding of diagnoses and procedures; however, race and ethnicity are often not collected systematically and individual socioeconomic information is typically not collected at all.

Related constraints were posed by the availability of data for subpopulations. While important differences in health care exist within some of the populations we examined, such as among Hispanic and Asian subpopulations from different countries of origin, many data sets do not collect this level of detailed data on race/ethnicity. Even among those that do, small sample sizes generally precluded such analysis. Ultimately, the report relied on the racial/ethnic categories specified by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for the collection of federal data.8 The main data included in the report based on this classification were supplemented by data from the California Health Interview Survey, one of the few large survey efforts with adequate sample to address subpopulation issues.

While OMB guidance was available to help specify racial disparities, comparable standards do not exist to help specify socioeconomic disparities. Researchers use a variety of measures of socioeconomic position, including income, poverty, education, occupation, wealth, class, and social capital, and consensus does not exist about which measure is best for examining disparities in health care. In the absence of specific guidance, NHDR focused on family income relative to federal poverty thresholds and education as commonly used and available measures of socioeconomic position and sought to include both dimensions when feasible.

The capacity to measure the existence of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in health care far exceeds the current knowledge of why such disparities exist and how to reduce them. Given the breadth of the Congressional mandate to provide a national overview of disparities in health care, the NHDR focuses on documenting existing disparities. The first report provides a baseline from which to track future trends in health care disparities.

Another challenge is to make a national snapshot of health care disparities useful to physicians and other providers. Though the data are presented at a national level, disparities are likely to vary substantially by community for different populations.9 It is hoped that this report can provide a template for local improvement and help to target improvement initiatives by stakeholders, such as clinicians, physician organizations, and community-based organizations.

Efforts to reduce disparities and improve quality need to be coordinated to ensure that they complement rather than impede each other. It is hoped that these data will stimulate discussion about the leadership role of physicians in reducing health care disparities and improving quality of care together.

ROLE OF GENERAL INTERNISTS IN REDUCING DISPARITIES

Since general internists serve as “navigators” for patients through a complex health care system, the data on disparities for different populations with specific priority conditions should help to target our efforts. If we know that a particular patient population is less likely to receive high-quality care for a given condition, we can more effectively advocate for the services that these patients need. Given the important role of general internists in medical education, the report should also provide important material for teaching. As we review the clinical care for patients with a given condition, we can use the data from the NHDR to highlight the disparities that certain populations may face without culturally competent interventions. Lastly, primary care physicians are effective advocates for health care policies and systems that ensure high-quality care for all Americans.10

Maximizing the usefulness of the NHDR to providers will require critical review of the report each year. Primary care physicians were instrumental in crafting the first NHDR, leading the development of measures and methods used in the report and the interpretation of analytic results. It is hoped that they will continue to shape future reports and make them accessible and useful to providers engaged in clinical care, teaching, and advocacy. Specific areas where input from primary care physicians is sought include refining and adding to the NHDR measure set, improving the presentation of findings, translating NHDR methods into practical tools, and integrating disparities measurement into practice.

CONCLUSIONS

Disparities in health care are of concern to health care providers and the general public alike for a variety of reasons. Perhaps most pressing is the nation's changing demographics, which reveals that minorities are growing at a much more rapid pace than whites.11 Concurrently, gaps in income between the richest and poorest households in America are widening.12 In addition, a solution to eliminating disparities in health care is not readily apparent. The purpose of this first national report is to provide a broad overview of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic health care disparities in the US, thereby contributing to the public dialogue on how to improve the quality of health care delivery for all Americans. It will identify areas in health care where disparities exist, forming the critical foundation for future versions of the NHDR, which will examine causes of disparities and discuss shaping solutions to the problem. Other goals for subsequent years include adding measures specific to particular priority populations, adding analyses of disparities along the rural–urban continuum, and further coordination with public and private organizations to standardize core elements of national and subnational surveys.

While disparities have been found in access and quality of many high technology and specialty services, the primary care physician will play a critical role in any solution for reducing health care disparities. In the unique position to provide primary and preventive care to patients for many conditions where disparities in health care are manifest, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, primary care physicians can serve as patient advocates and agents for change in reducing these disparities. The existence of an annual national report documenting trends in racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in health care, such as the NHDR, may help providers and policy makers target efforts to eliminate health care disparities. Primary care physicians play a critical role in improving and making the NHDR useful to clinicians.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:618–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Healthcare Research and Quality Act of 1999. Public Law no. 106–129. 42 U.S.C. 299 Sections 902 (g) and 913 (b) (2).

- 4.Hurtado MP, Swift EK, Corrigan JM, editors. Envisioning the National Health Care Quality Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swift EK, editor. Guidance for the National Healthcare Disparities Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter-Pokras O, Baquet C. What is a ‘Health Disparity’? Public Health Rep. 2002;117:426–34. doi: 10.1093/phr/117.5.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Office of Management and Budget. Provisional Guidance on the Implementation of the 1997 Standards for Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/inforeg/r&e_guidance2000update.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2004.

- 9.Skinner J, Weinstein JN, Sporer SM, Wennberg JE. Racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in rates of knee arthroplasty among Medicare patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1350–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bigby J, editor. Cross-Cultural Medicine. Philadelphia Pa: American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hobbs F, Stoops N. Demographic Trends in the 20th Century. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones AF, Weinberg DH. The Changing Shape of the Nation's Income Distribution 1947–98. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; 2000. [Google Scholar]