Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To describe the practice settings, financial arrangements, and management strategies experienced by generalist physicians and identify factors associated with reporting pressure to limit referrals, pressure to see more patients, and career dissatisfaction.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional mail survey.

PARTICIPANTS AND SETTING

Six hundred nineteen generalist physicians (62% response rate) caring for managed care patients in 3 Minnesota health plans during 1999.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Twenty-six percent of physicians reported pressure to limit referrals. In adjusted analyses, female physicians and those who were board certified acted as gatekeepers for most of their patients, received incentives based on performance reports and quality profiles, and received direct income from capitation, and were more likely than others to report this pressure (all P < .05). Sixty-two percent reported pressure to see more patients. In adjusted analyses, this pressure was more frequent among physicians in practices owned by health systems, those using physician extenders, and among physicians paid by salary with performance adjustment or those receiving at least some capitation (all P < .05). One-quarter (24%) of physicians were dissatisfied with their career in medicine. In adjusted analyses, physicians reporting pressure to limit referrals (risk ratio, 1.12; 95% confidence interval, 1.01 to 1.19) and those reporting pressure to see more patients (risk ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.08 to 1.66) were more likely to be dissatisfied than other physicians.

CONCLUSIONS

Pressures to limit referrals and to see more patients are common, particularly among physicians paid based on productivity or capitation, and they are associated with career dissatisfaction. Whether future changes in practice arrangements or compensation strategies can decrease such physician-reported pressures, and ultimately improve physician satisfaction, will be an important area for future study.

Keywords: physician satisfaction, managed care

Recent literature suggests that physicians have become increasingly dissatisfied with the practice of medicine,1,2 a trend that may have important consequences. Patients of physicians who are dissatisfied may be less adherent to treatment recommendations3 and less satisfied with their care than other patients,4,5 and one study suggests that physicians with negative feelings about their work prescribe more medications and provide their patients with less information.6 Moreover, dissatisfaction among primary care physicians may be associated with greater job turnover,7–9 and such turnover may have large cost implications.10

Physicians practicing in managed care settings or in areas with greater market share of managed care appear to be less satisfied than other physicians.11–13 Data suggest that limits on physician autonomy that are often associated with managed care, such as pressures to see more patients or to limit referrals to specialists, may be a mechanism for this association.12–14

Despite decades of experience with managed care, descriptions of physicians' practice environments, including their practice settings, financial arrangements, and the management strategies under which they work, remain few. More important, little is known about whether specific features of physicians' practices or their arrangements with health care organizations contribute to less autonomy or decreased satisfaction.13 In this study, we surveyed generalist physicians providing care to managed care patients in Minnesota and examined whether practice characteristics, management strategies, and financial arrangements were associated with physicians' reports of experiencing pressure to limit referrals or to see more patients and of being dissatisfied with their career in medicine.

METHODS

Study Design

This report is part of a larger study conducted in collaboration with 3 health plans in Minnesota to examine how features of managed care influence quality of care for patients with diabetes and hypertension. Because physicians' practices have evolved differently under the influence of managed care in different markets,15 we focus our study on physicians' experiences in a single market in order to control for unmeasured market characteristics.

Using administrative encounter data, we sampled eligible patients who had at least 2 visits with diagnosis codes for either diabetes or hypertension from July 1, 1997 through December 31, 1998. We assigned a physician to each patient by selecting the physician with whom the patient had the most outpatient visits with a diagnosis code for either diabetes or hypertension (depending on the condition of interest) during the 18-month period. For cases in which a patient had the same number of such visits to 2 or more physicians, we selected the physician with the greatest number of total visits. If more than one physician provided the same number of total visits, we selected the primary care physician or, if no primary care physician provided care, we selected the physician most likely to provide care based on specialty (for example, if a patient with diabetes saw an oncologist and endocrinologist, we selected the endocrinologist). We identified 1,162 physicians caring for the 2,670 patients in the sample. During the fall of 1999, we mailed a survey (described below) to each physician with a $20 incentive. Nonrespondents were recontacted by mail and telephone. After excluding 84 physicians who were still in residency training, 666 of 1,078 physicians responded to the survey, for a response rate of 62%. Respondents did not differ from nonrespondents by age (P = .83) or gender (P = .19). We excluded 42 physicians who were not general internists or family practitioners and 5 physicians who did not respond to the questions of primary interest, leaving a final sample of 619 physicians.

Questionnaire

The survey instrument was designed to collect information about physicians' personal characteristics, as well as features of their practice, their compensation arrangements, and practice management strategies that are often used by health care organizations to influence care.16 Specifically, with respect to their personal and practice characteristics, we asked about specialty, board certification status, practice type and setting, practice ownership, the number of physicians in the practice, and the number of physician assistants and nurse practitioners (physician extenders) in the practice. Questions about clinical workload and patient populations included the proportion of time in direct patient care, the number of patients seen per week, the proportion of patients in managed care plans, the proportion of patients with Medicare, Medicaid, other health insurance, or no health insurance, and the proportion of their patients for whom health plans reimburse using capitation. To determine compensation for their work during 1998, we asked about their base clinical income, percent of total income derived from bonuses or returned withholds or other incentives, and whether their pay was affected by 1) results of satisfaction surveys completed by their own patients, 2) specific measures of quality of care, such as rates of preventive care services, and 3) the results of performance reports of utilization profiles that compared their pattern of using medical resources with that of other physicians. We also asked whether the physician was part of a risk pool (defined as a group of physicians that share in the reward or penalty from surpluses or deficits in capitation payments or referral budgets). With respect to practice management characteristics, we asked about the proportion of their patients for whom they are required to provide referrals for specialty care (serve as a gatekeeper), whether they had received utilization profiles or performance reports and the number of sources of such reports, whether they had received guidelines (for diabetes and/or hypertension), and whether their practice used computerized medical records.

To examine perceived limits on autonomy, we asked physicians whether, in the last 12 months, they felt they were encouraged to limit the number of referrals they made or to see a large number of patients each day.14 Physicians responding yes to either question were asked whether they believed that patient care was compromised because of this. Finally, to measure satisfaction, we asked physicians: “Thinking generally about your overall career in medicine, would you say that you are currently: very satisfied, generally satisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied.” We categorized physicians as dissatisfied if they responded somewhat or very dissatisfied.

Analysis

We described characteristics of physicians, their practice type and setting, characteristics of their patients and patient volume, their compensation, and their practice management, and then used the χ2 test to identify bivariate associations between these characteristics and feeling 1) encouraged to limit referrals, 2) encouraged to see a large number of patients, and 3) dissatisfied with their career in medicine.

We conducted analyses in 2 stages. First, we used logistic regression to determine which factors were independently associated with each of the 3 dependent variables of interest. Models included the independent variables listed in Table 1. We included all variables of interest in the models because we wanted to identify all possible explanatory factors for our outcomes of interest. Because we were concerned about multicollinearity, we examined correlations among the independent variables; all correlation coefficients were <0.35 with the exception of correlations among the 3 types of incentives affecting pay. For these variables, we examined separate models that included the variables individually. Compared to the model that included all 3 of these variables, the associations we observed when the variables were included individually were unchanged except where noted.

Table 1.

Physician Characteristics, Practice Management, and Financial Arrangements and Pressure to Limit Referrals, to See a Large Number of Patients, and Dissatisfaction

| Total, n (%) | Encouraged to Limit Referrals, % | P Value | Encouraged to See a Large Number of Patients, % | P Value | Dissatisfied with Career in Medicine, % | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 619 (100) | 26 | 62 | 24 | |||

| Physician characteristics* | |||||||

| Age, y <40 | 153 (25) | 24 | 61 | .007 | 15 | .02 | |

| 40–49 | 260 (42) | 29 | .49 | 69 | 26 | ||

| 50–59 | 152 (25) | 22 | 57 | 30 | |||

| 60+ | 51 (8) | 25 | 47 | 22 | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 480 (78) | 23 | .006 | 67 | .20 | 25 | .82 |

| Female | 138 (22) | 35 | 61 | 24 | |||

| Specialty | |||||||

| Family practice | 447 (72) | 26 | .81 | 60 | .12 | 23 | .64 |

| Internal medicine | 172 (28) | 25 | 67 | 25 | |||

| Board certified | |||||||

| No | 41 (7) | 12 | .04 | 49 | .07 | 22 | .77 |

| Yes | 578 (93) | 27 | 63 | 24 | |||

| Practice type and setting | |||||||

| Primary practice type | |||||||

| Single-specialty group | 250 (40) | 28 | .64 | 62 | .73 | 25 | .24 |

| Multispecialty group | 308 (50) | 25 | 63 | 25 | |||

| Other | 61 (10) | 23 | 57 | 15 | |||

| Owner | |||||||

| Physician-owned | 302 (49) | 32 | .003 | 56 | .002 | 21 | .34 |

| Health system | 211 (34) | 20 | 71 | 26 | |||

| Medical school, government, or insurance company | 106 (17) | 19 | 62 | 27 | |||

| Number of MDs | |||||||

| 1–5 | 182 (29) | 24 | .85 | 58 | .27 | 25 | .42 |

| 6–15 | 255 (41) | 27 | 66 | 26 | |||

| 16+ | 172 (28) | 27 | 59 | 20 | |||

| Don’t know | 10 (2) | 20 | 70 | 10 | |||

| Physician extenders in practice | |||||||

| No | 158 (26) | 26 | .93 | 55 | .04 | 19 | .10 |

| Yes | 461 (74) | 26 | 64 | 25 | |||

| Types of patients in practice and workload | |||||||

| Greater than 50% of patients in managed care | |||||||

| No | 217 (35) | 20 | .02 | 57 | .06 | 21 | .21 |

| Yes | 402 (65) | 29 | 65 | 25 | |||

| Greater than 30% patients in Medicare | |||||||

| No | 423 (68) | 28 | .04 | 63 | .32 | 23 | .58 |

| Yes | 196 (32) | 20 | 59 | 25 | |||

| More than 20% of patients with Medicaid or no insurance | |||||||

| No | 454 (73) | 28 | .03 | 63 | .28 | 24 | .69 |

| Yes | 146 (24) | 18 | 58 | 24 | |||

| Don’t know | 19 (3) | 16 | 74 | 16 | |||

| Patients for whom health plan reimburses with capitation | |||||||

| <30% | 378 (61) | 24 | .002 | 62 | .86 | 21 | .16 |

| 30% or more | 181 (29) | 34 | 64 | 29 | |||

| Don’t know | 60 (10) | 12 | 60 | 24 | |||

| Clinical workload (patients seen per week corrected for percent of time in clinical practice) | |||||||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 154 (25) | 25 | .87 | 61 | .26 | 26 | .51 |

| Quartile 2 | 118 (19) | 23 | 69 | 28 | |||

| Quartile 3 | 194 (31) | 27 | 63 | 22 | |||

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 153 (25) | 27 | 57 | 21 | |||

| Physician compensation | |||||||

| Base clinical payment | |||||||

| Salary, does not depend on performance | 144 (23) | 21 | .005 | 55 | .009 | 18 | .22 |

| Salary, depends on performance | 274 (44) | 26 | 67 | 27 | |||

| FFS | 114 (18) | 21 | 54 | 22 | |||

| Mixture of FFS and capitation | 87 (14) | 40 | 69 | 25 | |||

| Bonus, % | |||||||

| 0 | 302 (49) | 22 | .10 | 63 | .59 | 23 | .52 |

| 1–10 | 173 (28) | 31 | 62 | 27 | |||

| 11+ | 127 (21) | 28 | 61 | 23 | |||

| Don’t know | 17 (3) | 18 | 47 | 12 | |||

| Pay affected by satisfaction surveys completed by their patients | |||||||

| No | 481 (78) | 24 | .03 | 63 | .47 | 23 | .33 |

| Yes | 138 (22) | 33 | 59 | 27 | |||

| Pay affected by measures of quality, such as rates of preventive care services | |||||||

| No | 506 (82) | 23 | .001 | 62 | .81 | 24 | .76 |

| Yes | 113 (18) | 40 | 61 | 25 | |||

| Pay affected by performance reports or utilization profiles compared to other physicians | |||||||

| No | 494 (80) | 22 | .001 | 62 | .61 | 24 | .74 |

| Yes | 125 (20) | 42 | 64 | 25 | |||

| Part of risk pool | |||||||

| No | 481 (78) | 22 | .001 | 61 | .38 | 23 | .49 |

| Yes | 138 (22) | 37 | 65 | 26 | |||

| Practice management | |||||||

| Required to provide referrals for > 50% of patients | |||||||

| No | 400 (65) | 21 | .001 | 59 | .05 | 22 | .24 |

| Yes | 219 (35) | 34 | 67 | 27 | |||

| Received quality performance report or utilization profile (in past year) | |||||||

| No | 71 (11) | 18 | .02 | 54 | .18 | 25 | .09 |

| Yes, from 1 source | 256 (41) | 22 | 61 | 19 | |||

| Yes, from 2 or more sources | 292 (47) | 31 | 65 | 27 | |||

| Received guidelines for diabetes or hypertension care from practice, health plan, or local organization | |||||||

| No | 209 (34) | 22 | .19 | 64 | .45 | 28 | .09 |

| Yes | 410 (66) | 27 | 61 | 22 | |||

| Use computerized medical records | |||||||

| No | 542 (88) | 26 | .83 | 62 | .57 | 25 | .16 |

| Yes | 72 (12) | 25 | 65 | 17 |

Missing values were present for 3 physicians on age and 1 physician on gender.

FFS, fee-for-service.

Second, to assess the extent to which perceived limits on autonomy were associated with dissatisfaction, we refit the model examining factors associated with dissatisfaction, first including whether the physician reported feeling pressure to limit referrals and second, including whether the physician reported feeling pressure to see a large number of patients.

Analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 6.12 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). We converted adjusted odds ratios to risk ratios to more accurately reflect the relative risk.17 The study protocol was approved by the Harvard Medical School Committee on Human Studies and by participating health plans.

RESULTS

Physician Demographics and Practice Arrangements

Physicians in the sample had a mean age of 46 years, 78% were men, and 93% were board certified (Table 1). Most were family practitioners (72%), with the remainder general internists (28%). They saw a mean of 89 (SD 39) patients per week and 49% reported spending 90% or more of their time in direct patient care.

Half of the physicians practiced in multispecialty groups and 40% practiced in single-specialty groups. Sixty-five percent reported that more than half of their patients were enrolled in managed care (including patients enrolled in either Medicare or Medicaid managed care). A mean of 28% of physicians' patients were covered by Medicare, 12% by Medicaid, 50% by other health insurance (including managed care and indemnity), and 6% had no insurance.

Physician Compensation

Twenty-three percent of physicians received a salary for their base clinical income that was not adjusted based on productivity (the revenue generated or the number of patients seen over the past year or quarter). Another 44% were paid by salary with adjustment for productivity. Eighteen percent had a base income that was exclusively fee-for-service, and 14% were paid by a mixture of fee-for-service and capitation. Nearly half (49%) of physicians reported some income in the form of bonuses, returned withholds, or other incentive payments based on performance, with the median size of the bonus 10% (among those receiving bonuses). When asked about specific types of incentives affecting pay, 22% reported that their pay was affected by results of patient satisfaction surveys completed by their own patients, 18% reported that their pay was affected by specific measures of quality of care such as rates of preventive care services for their patients, and 20% reported that their pay was affected by results of performance reports or utilization profiles that compared their pattern of using medical resources to treat patients with that of other physicians. Twenty-nine percent of physicians reported that more than 30% of their patients were cared for under capitation contracts (median among physicians with any capitated patients, 30%).

Practice Management

Although a majority of physicians reported that more than 50% of their patients were enrolled in managed care plans, only 35% served as a gatekeeper for at least half of their patients, likely reflecting the trend away from gatekeeping arrangements in the late 1990s.18 Most (89%) physicians reported receiving quality performance reports or utilization profiles in the past year, with 47% reporting receiving them from 2 or more sources. Sixty-six percent reported that a practice, health system, hospital, or health plan provided practice guidelines for diabetes or hypertension care. Only 12% of physicians used a computerized medical record.

Pressure to Limit Referrals

Approximately one-quarter of respondents (26%) reported feeling encouraged to limit referrals. Among this group, 24% believed this pressure compromised patient care. In unadjusted analyses (Table 1), female and board-certified physicians, physicians working in physician-owned practices, and those with more managed care patients and fewer Medicare or Medicaid patients were more likely to feel encouraged to limit referrals than their counterparts (Table 1). Similarly, physicians with more patients for whom health plans reimbursed using capitation, physicians paid at least partly by capitation, those who were part of a risk pool, those who received incentives, those who served as a gatekeeper for more than half of their patients, and those who received quality performance reports or utilization profiles from more than 2 sources were also more likely to report pressure to limit referrals (Table 1).

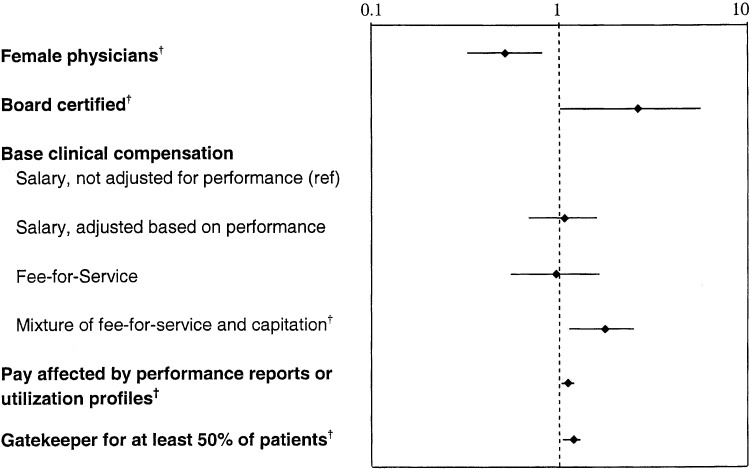

In multivariable analysis, male physicians were less likely than female physicians to feel encouraged to limit referrals (risk ratio [RR], 0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.33 to 0.81; Fig. 1), and board-certified physicians were more likely than others to report this pressure (RR, 2.59; 95% CI, 1.01 to 5.06). Compared to physicians who were paid a salary without adjustment for productivity, physicians paid by a mixture of fee-for-service and capitation were more likely to feel encouraged to limit referrals (RR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.12 to 2.49). Physicians who reported that their pay was affected by the results of performance reports or utilization profiles were also more likely than others to report being encouraged to limit referrals (RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.18), as were physicians who served as a gatekeeper for at least 50% of their patients (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.29). In additional analyses, we tested the separate effect of whether incentives based on patient surveys, quality measures, or performance reports/utilization profiles were associated with pressure to limit referrals (because these variables were correlated). When we added each of the 3 incentive variables separately to the model, we found that incentives based on performance reports or utilization profiles and incentives based on quality indicators were both associated with reporting pressure to limit referrals.

FIGURE 1.

Factors associated with feeling pressure to limit referrals.** Model includes all variables in Table 1. Only factors significantly related to pressure to limit referrals are depicted, using a logarithmic scale. † P < .05.

Pressure to See a Large Number of Patients

A majority of physicians (62%) reported feeling encouraged to see a large number of patients, and 32% of these physicians believed that this compromised patient care. In unadjusted analyses (Table 1), physicians who were in their 40s were most likely to feel encouraged to see many patients, with the oldest physicians least likely to feel this way. Physicians who were part of a health system, had physician extenders in the practice, were paid by salary that was adjusted depending on productivity or paid by a mixture of fee-for-service and capitation, and who were required to provide referrals for at least half of their patients were more likely to feel encouraged to see more patients.

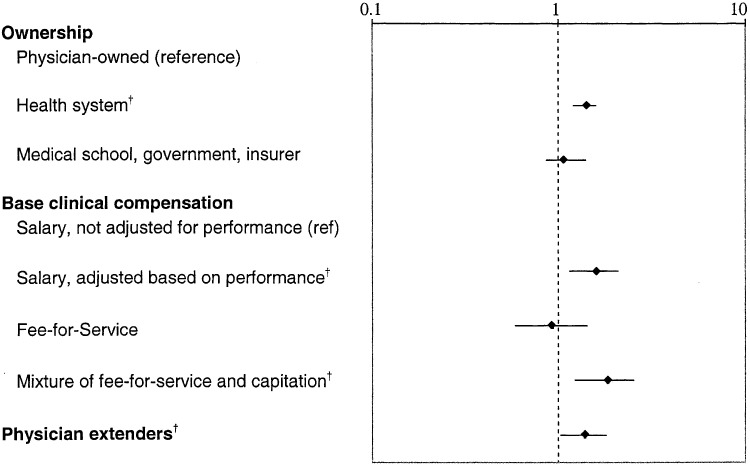

In multivariable analysis, physicians whose practice was owned by a health system (compared to being physician-owned) more often reported feeling encouraged to see a large number of patients each day (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.20 to 1.58; Fig. 2), despite the fact that such physicians had slightly lower clinical workloads (29% of physicians in physician-owned practices were in the highest quartile of clinical workload compared to 20% of physicians in health system-owned practice and 22% of those in other practices; P = .07). Also, physicians in practices with physician extenders were more likely than others to feel encouraged to see many patients (RR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.80). Compared to physicians paid by salary without adjustment for productivity, physicians paid by salary with adjustment for productivity (RR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.13 to 2.10) and physicians paid by a mixture of fee-for-service and capitation (RR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.21 to 2.52) were more likely than others to feel encouraged to see many patients.

FIGURE 2.

Factors associated with feeling pressure to see more patients.** Model includes all variables in Table 1. Only factors significantly related to pressure to see more patients are depicted, using a logarithmic scale. † P < .05.

Dissatisfaction

Twenty-four percent of physicians reported being somewhat or very dissatisfied with their careers in medicine. This proportion was greatest among physicians in their 50s and lowest among the youngest and oldest physicians (Table 1). No other physician or practice characteristics were significantly associated with dissatisfaction in unadjusted analyses.

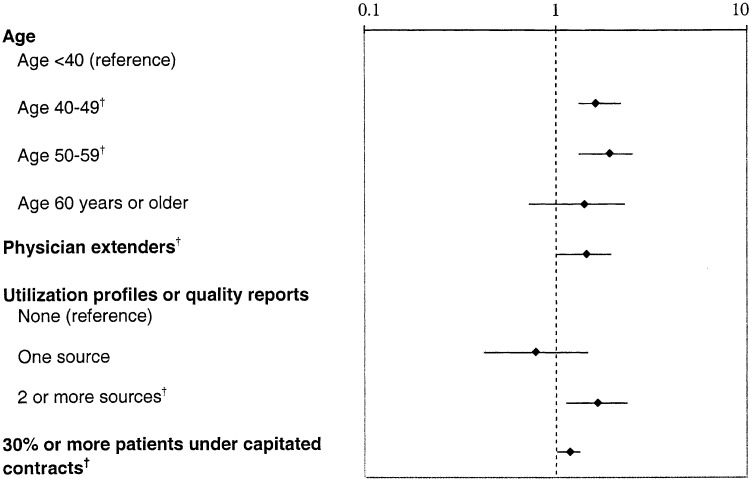

In multivariable analyses, physicians in their 40s and 50s were more dissatisfied than younger physicians (compared to physicians <40 years; RR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.11 to 2.16 for physicians 40 to 49; and RR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.31 to 2.52 for physicians 50 to 59; Fig. 3). Physicians aged 60 and older did not differ significantly from the youngest physicians (RR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.71 to 2.28). Also, physicians working in practices that employed physician extenders were also more dissatisfied than other physicians (RR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.94). Those who reported that health plans reimbursed by capitation for 30% or more of their patients were more dissatisfied than other physicians (RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.3), as were physicians who received quality performance reports or utilization profiles from 2 or more sources (compared to not receiving such reports or profiles; RR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.12 to 2.33).

FIGURE 3.

Factors associated with dissatisfaction with career in medicine.** Model includes all variables in Table 1. Only factors significantly related to dissatisfaction are depicted, using a logarithmic scale. † P < .05.

Relationship Between Pressures to Limit Referrals or See More Patients and Dissatisfaction

Physicians who reported that they were encouraged to limit referrals and those who reported that they were encouraged to see a large number of patients were more likely than other physicians to be dissatisfied (Table 2). In a multivariable model, also adjusting for all other physician and practice factors, physicians who felt encouraged to limit referrals were more dissatisfied than other physicians (RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.19). This finding did not change the significance of other variables in the model, except for the relationship between having 30% or more capitated patients in the practice, which was now only of borderline significance (P = .06). In another multivariable model adjusting for physician and practice factors, feeling encouraged to see more patients was also associated with dissatisfaction (RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.66). In this model, working in a practice that employed physician extenders was no longer statistically significantly associated with dissatisfaction (P = .06).

Table 2.

Limits on Autonomy and Association with Dissatisfaction

| Total, n (%) | Dissatisfied (Somewhat or Very), % | P Value | Adjusted Risk Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 619 (100) | 24 | |||

| Limits on autonomy | |||||

| Encouraged to limit referrals | |||||

| No | 457 (74) | 21 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 159 (26) | 31 | .02 | 1.12 | 1.01 to 1.19 |

| Encouraged to see many patients | |||||

| No | 234 (38) | 17 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 382 (62) | 28 | .001 | 1.37 | 1.08 to 1.66 |

CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

We surveyed generalist physicians caring for patients with 2 common chronic medical conditions enrolled in 1 of 3 health plans in Minnesota. These physicians worked in a variety of different practice settings with varying practice arrangements, compensation schemes, and management strategies. One-quarter of these physicians were dissatisfied with their overall career in medicine, a finding which varied little based on practice setting, but was strongly associated with perceived limits on autonomy such as pressures to limit referrals or see more patients.

A substantial proportion of physicians in our study felt pressure to limit referrals (24%) or see more patients (62%); however, these pressures were less pervasive than among primary care physicians in California with managed care contracts, where 57% of physicians felt pressure to limit referrals and 75% of physicians felt pressure to see more patients.14 This difference may be due to the high prevalence of capitation in California,19,20 which may be associated with more limits on autonomy. Similar to California physicians, physicians in our study who reported incentives based on results of performance reports or utilization profiles were more likely to feel pressure to limit referrals.

Our findings that physicians paid in part by capitation and that physicians who served as a gatekeeper for the majority of their patients were more likely to feel pressure to limit referrals likely reflect real strategies to contain costs that are often used by medical groups with capitation contracts.21 Our finding that female physicians were more likely to feel pressure to limit referrals is consistent with other data suggesting that female physicians refer more patients.22 If female physicians generally refer patients at a higher rate, then they may sense a relatively greater pressure to limit referrals due to efforts in their practice setting to control costs and limit use of specialty care.

Most physicians in our sample reported pressures to see a large number of patients. Physicians who worked in a practice owned by a health system were more likely to feel this pressure than those in physician-owned practices (who had slightly higher clinical workloads). Physicians who are owners of their practices have control over their productivity, which may be more satisfying than having productivity targets set externally by a health system. Such external pressures to increase productivity may also explain why physicians in practices that employed physician extenders report greater pressure to see more patients, because this may be a marker for the practice's attempts to increase the overall productivity of the practice and may allow the practice to take on more capitated patients. In addition, physicians may be responsible for reviewing cases with these physician extenders, thus increasing their effective patient volume. The method of physician compensation was also related to feeling pressure to see more patients. Physicians paid by salary that depends on performance may feel pressure to see more patients to maintain their target salary, and those who are paid at least partially by capitation may feel pressure to increase their panel size, which may translate to responsibility for more patients.

One-quarter of physicians in our sample reported that they were dissatisfied with their overall career in medicine. Similar to other reports,23,24 middle-aged physicians were least satisfied with their career in medicine. These physicians, who are in the prime of their careers, likely have different expectations than the oldest physicians who were beyond their highest earnings years, and the youngest physicians who were acculturated to practice in the 1990s. Physicians in practices employing physician extenders were less satisfied than others. If physician extenders see a disproportionate share of less complicated patients, the physicians in these practices may then predominately care for the practice's sickest patients, which could make their jobs more stressful and thus less satisfying. Alternatively, if physicians derive satisfaction from continuity in relationships with their patients, and use of physician extenders limits that continuity, their satisfaction may decrease. Our finding that physicians who had more than 30% of their patients for whom the practice has capitated contracts were more dissatisfied is consistent with other data demonstrating that physicians who take care of larger numbers of capitated patients are less satisfied with the quality of care they can provide to these patients25 and have lower overall satisfaction.12

Physicians who felt encouraged to limit referrals and to see more patients were more dissatisfied, similar to physicians in California14 and consistent with other findings that decreased autonomy and increased time pressure are associated with lower satisfaction.12,13 These variables were not, however, a mechanism to explain other factors associated with dissatisfaction. In other studies, decreased autonomy and increased time pressures have explained dissatisfaction associated with managed care comparing physicians with varying levels of participation in managed care; in our study, most physicians had a large number of managed care patients and the proportion of patients in managed care was not associated with dissatisfaction.

Our study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, our physician sample was not population based, but rather representative of physicians caring for patients with diabetes or hypertension enrolled in 3 health plans. Nearly all generalist physicians, however, care for patients with these conditions, and almost all of the physicians in the sample care for patients enrolled in most or all other plans in the state. Second, we studied care in only 1 health care market. Although our findings may not be generalizable to other markets, it is nevertheless important to understand physicians' experiences even within markets. Moreover, the similarity of many of our findings to national data26 suggests that this market is not markedly different. Third, our sample included only physicians who cared for patients who were enrolled in managed care plans. However, 95% of physicians nationwide participate in managed care.26 Fourth, our study is subject to nonresponse bias. If nonrespondents were under more time pressure than respondents, we may have underestimated the prevalence of such pressures and of dissatisfaction. Finally, although we measured many characteristics of physicians' practices, we did not collect information about their ability to choose their office staff or control the number of hours they worked, nor did we measure their perceptions about increases in paperwork or limits on prescribing and test ordering, all of which may impact satisfaction.

In summary, generalist physicians in Minnesota who care for managed care patients work in a variety of settings. Pressures to limit referrals and to see more patients are common, particularly among physicians paid based on productivity, and are associated with dissatisfaction with one's career. Whether future changes in compensation strategies can decrease such physician-reported pressures, and ultimately improve physician satisfaction, will be an important area for future study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant HS09936 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and grant HS98-005 from the American Association of Health Plans.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray A, Montgomery JE, Chang H, Rogers WH, Inui T, Safran DG. Doctor discontent. A comparison of physician satisfaction in different delivery system settings, 1986 and 1997. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:452–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007452.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landon BE, Reschovsky JD, Blumenthal D. Changes in career satisfaction among primary care and specialist physicians 1997–2001. JAMA. 2003;289:442–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, et al. physicians' characteristics influence patients' adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychol. 1993;12:93–102. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.12.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linn LS, Brook RH, Clark VA, Davies AR, Fink A, Kosecoff J. Physician and patient satisfaction as factors related to the organization of internal medicine group practices. Med Care. 1985;23:1171–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198510000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:122–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grol R, Mokkink H, Smits A, et al. Work satisfaction of general practitioners and the quality of patient care. Fam Pract. 1985;2:128–35. doi: 10.1093/fampra/2.3.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rusbult CE, Farrell D, Rogers G, Mainous AG., III The impact of exchange variables on exit, voice, loyalty and neglect: an integrative model of responses to declining job satisfaction. Acad Manag J. 1988;31:599–627. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mainous AG, III, Ramsbottom-Lucier M, Rich EC. The role of clinical workload and satisfaction with workload in rural primary care physician retention. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:787–92. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchbinder SB, Wilson M, Melick CF, Powe NR. Primary care physician job satisfaction and turnover. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7:701–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchbinder SB, Wilson M, Melick CF, Powe NR. Estimates of costs of primary care physician turnover. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5:1431–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadley J, Mitchell JM. Effects of HMO market penetration on physicians' work effort and satisfaction. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997;16:99–111. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.6.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, et al. Managed care, time pressure, and physician job satisfaction: results from the physician worklife study. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:441–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.05239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoddard JJ, Hargraves JL, Reed M, Vratil A. Managed care, professional autonomy, and income. Effects on physician career satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:675–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grumbach K, Osmond D, Vranizan K, Jaffe D, Bindman AB. Primary care physicians' experience of financial incentives in managed-care systems. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1516–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal MB, Landon BE, Huskamp HA. Managed care and market power: physician organizations in four markets. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20:187–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.5.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landon BE, Wilson IB, Cleary PD. A conceptual model of the effects of health care organizations on the quality of medical care. JAMA. 1998;279:1377–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Draper DA, Hurley RE, Lesser CS, Strunk BC. The changing face of managed care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:11–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson JC, Casalino LP. The growth of medical groups paid through capitation in California. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1684–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson JC. Blended payment methods in physician organizations under managed care. JAMA. 1999;282:1258–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.13.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerr EA, Mittman BS, Hays RD, Siu AL, Leake B, Brook RH. Managed care and capitation in California: how do physicians at financial risk control their own utilization? Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:500–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-7-199510010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franks P, Clancy CM. Referrals of adult patients from primary care: demographic disparities and their relationship to HMO insurance. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haas JS, Cleary PD, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cook EF, Brennan TA. Differences in the professional satisfaction of general internists in academically affiliated practices in the greater-Boston area. Ambulatory Medicine Quality Improvement Project Investigators. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:127–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landon BE, Aseltine R, Shaul JA, Miller Y, Auerbach BA, Cleary PD. Evolving dissatisfaction among primary care physicians. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:890–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerr EA, Hays RD, Mittman BS, Siu AL, Leake B, Brook RH. Primary care physicians' satisfaction with quality of care in California capitated medical groups. JAMA. 1997;278:308–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stoddard JJ, Reschovsky JD, Hargraves JL. Managed care in the doctor's office: has the revolution stalled? Am J Manag Care. 2001;7:1061–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]