Abstract

We hypothesized that the Internet could be used to disseminate and evaluate a curriculum in ambulatory care, and that internal medicine residency program directors would value features made possible by online dissemination. An Internet-based ambulatory care curriculum was developed and marketed to internal medicine residency program directors. Utilization and knowledge outcomes were tracked by the website; opinions of program directors were measured by paper surveys. Twenty-four programs enrolled with the online curriculum. The curriculum was rated favorably by all programs, test scores on curricular content improved significantly, and program directors rated highly features made possible by an Internet-based curriculum.

Keywords: curriculum, computer-assisted instruction

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires residency training programs to document and evaluate the educational experience of trainees.1 Written curricula must be available for each of the training experiences, and self-assessment techniques should be available for a house officer to track his or her progress.1 Annual evaluation of the effectiveness of educational interventions must be completed. The desire to move to outcome-based education has been echoed elsewhere.2

In 2000–2001, there were 394 internal medicine residency training programs.3 It is likely that there is overlap in educational objectives among these programs, and that duplication of curricula exists.4–6 Curriculum development is commonly underfunded, and curricular evaluation to satisfy ACGME requirements will further tax resources.4 The need exists for greater globalization in medical education, and for development of common core curricula.2 However, resources for publishing curricula for dissemination are few; curricular interventions often fail to meet scientific requirements of medical journals.7 One method for sharing a common curriculum is the Internet. With the increasing use of computer-assisted instruction in education, it is likely that medical education will move increasingly online.2

We hypothesized that a curriculum in ambulatory care delivered via the Internet could be incorporated into a range of residency training programs. We also hypothesized program directors would rate features afforded by the Internet favorably, and would view this curriculum as a valuable educational resource.

METHODS

Curriculum Development

We developed a curriculum in ambulatory care using a 6-step approach to curriculum development.8 A needs assessment was performed by reviewing lists of the most common medical problems seen by internists in national surveys.9 In addition, current residents and recent graduates of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Osler Medical Residency Training Program were surveyed as to areas of perceived weakness in ambulatory care training. Seventeen topics were chosen for inclusion. Clinical cases were then written to illustrate learning objectives of curricular topics. Two multiple-choice questions were written for each learning objective; one was randomly selected for the pretest, with the other used for the posttest. Average module length was 7,800 words. Based on prior experience, it was anticipated that the average learner could complete a module in 20 to 40 minutes. Topics covered were: 1) hypertension, 2) back pain, 3) anemia, 4) immunizations, 5) cancer screening, 6) palliative care, 7) dementia, 8) preoperative assessment, 9) headaches, 10) osteoporosis, 11) depression, 12) gynecologic care, 13) preventive cardiology, 14) rashes, 15) diabetes, 16) hormone replacement, and 17) obesity. Sixteen faculty members from the Johns Hopkins Hospital contributed to curricular content, which was updated annually to reflect changes in the medical literature. Content could be directly copied to the website without programming or informatics expertise.

Website Structure

The website was built to accommodate a pretest-didactics-posttest curricular format, requiring completion of one section before accessing subsequent sections. No software other than an Internet browser was required to utilize the website. Pop-up message screens provided feedback on answer selections. The didactics section included descriptive summaries with links to abstracts (e.g., on PubMed) or full text articles (when available to the general public) of key studies (Fig. 1). Posttest completion was required before the module was registered as completed. Individuals could access their own scores, and compare them to group scores. Program directors determined which modules were available to their house staff, but had to post modules according to a predetermined schedule of when they were made available on the website. Program directors could track group scores (but not individual scores) for their training program, and compare them to aggregate scores for all participating programs. Program directors could access a list of modules completed by each of their house officers.

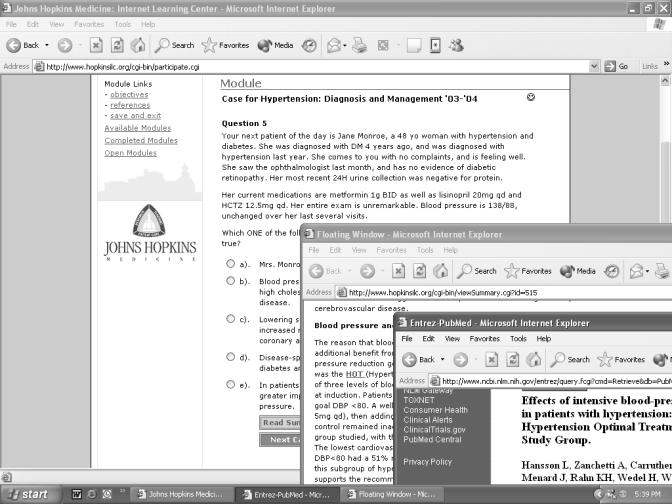

FIGURE 1.

Content display. The didactics section includes full text summary answers that explain the clinical decision and provides links to abstracts or full text articles of key studies.

Marketing

A brochure describing the website was sent with a cover letter to 409 members of the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine in early 2001 for enrollment in academic year 2001 to 2002. Program enrollment required an annual fee of $1,500.

Data Collection and Analysis

Individual utilization and group performance data were tabulated by the website throughout academic year 2001 to 2002. As the curriculum and website had been in use at Johns Hopkins Hospital 2 years prior to the initiation of this study, data from the Johns Hopkins Hospital were excluded from analysis. Utilization and test performance data were compared relative to characteristics of each residency training program. Program directors were surveyed at the completion of the year and again 10 months later, using a Likert-type scale of 1 (low/poor/strongly disagree) to 5 (high/excellent/strongly agree). The response rate for each questionnaire was 100%. Standard error, t tests, Wilcoxon rank sums, and confidence intervals were calculated by Excel (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, Wash) and SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill) software programs.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participating Internal Medicine Residency Training Programs

Twenty-four residency programs subscribed to the curriculum, comprising 1,749 house officers. Twelve programs (50%) were the primary affiliate of a medical school, while 10 programs (42%) were secondary affiliates. Six programs (25%) were small (30 or fewer house staff), 11 programs (46%) were moderate in size (31 to 90 house staff), and 7 programs (29%) were large (> 90 house staff). Included among participants were 2 programs among the top 10 NIH-funded medical centers, as well as several community hospitals.

Most program directors (83%) reported curriculum development as part of their job description. The majority of participating programs (83%) reported having an up-to-date ambulatory curriculum. Three-quarters of these programs continued to use elements of their own curriculum while implementing the online curriculum, most commonly group or in-clinic lecture.

Registration and Utilization

Twelve programs (50%) made the online curriculum required for trainees (mandatory programs), while 12 programs (50%) allowed voluntary use (voluntary programs). Three-quarters of mandatory programs used verbal or written reminders encouraging module completion, while one-quarter required module completion for ambulatory block credit or promotion. Registration rates of house officers varied widely among participating programs, ranging from 38.1% to 100%. In mandatory programs, registration averaged 88.6%, compared to 75.6% in voluntary programs (P = .04 by Wilcoxon rank sum). Registration among all participating programs averaged 82.7%. More than one-quarter (26.2%) of house staff across all programs either never registered for the website, or registered but never completed a module.

The most widely used module was hypertension, which was completed by 49.7% of all registrants. Completion rates for the 9 next most completed modules were immunizations (47.8%), diabetes (47.1%), headache (45.6%), hormone replacement (43.8%), cancer screening (41.2%), depression (37.1%), osteoporosis (36.4%), palliative care (36.2%), and gynecologic care (34.1%).

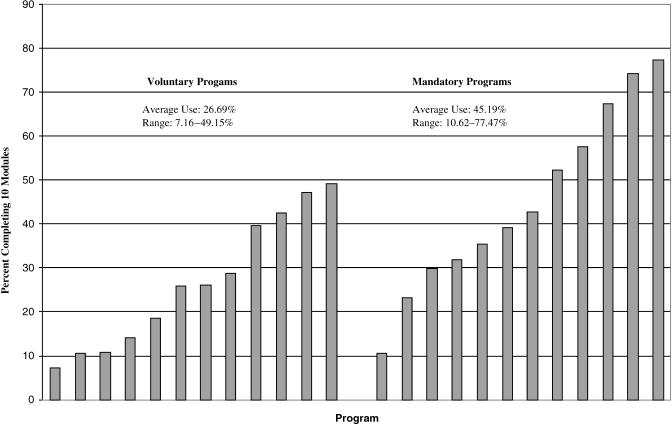

Utilization varied greatly among residency training programs. For each program's 10 most commonly completed modules, utilization ranged from 7.2% to 77.5%. For mandatory programs utilization across 10 modules was 45.2%, and was 26.7% for voluntary programs (P = .03 by paired t test; Fig. 2). Utilization was above average in those programs for which program directors checked utilization weekly as compared to less frequently (P = .034 by χ2 analysis), but e-mail reminders and conference announcements did not improve utilization. One program made completion of any 8 modules a requirement for promotion to the next year, and experienced full compliance with this requirement. Sixteen of the 24 programs (67%) used all 16 modules of the curriculum, while the others used an average of 13 of the 16 modules. Modules on back pain and dermatology were those least commonly used by participating programs.

FIGURE 2.

Average use by program. For each training program, the percentage of residents completing their 10 most commonly completed modules was calculated, and then grouped according to whether curriculum completion was voluntary or mandatory.

Evaluating the Curriculum

We evaluated the pretest and posttest scores of the 10 most commonly completed modules in the curriculum, comprising a total of 7,817 modules and 89,931 test questions. The average pretest score was 57.6%, while the average posttest score was 72.4% (P = .003 by paired t test). There was no difference in score improvement in mandatory as compared to voluntary programs, nor in programs that used additional teaching methods in conjunction with the online curriculum. Programs that had a preexisting ambulatory curriculum demonstrated slightly less improvement in scores when compared with those that did not (P < .05). Pretest scores were not higher in programs that had a preexisting ambulatory curriculum (P = .669).

Program directors rated the impact of the curriculum on their own knowledge and management of patients. On a Likert scale (1 = poor; 5 = excellent), program director rating of curricular content was 4.42 (standard deviation [SD], 0.65). All of the program directors who answered said they learned from the modules, that the curriculum impacted their management of patients, and that the curriculum had an impact on house staff management of patients.

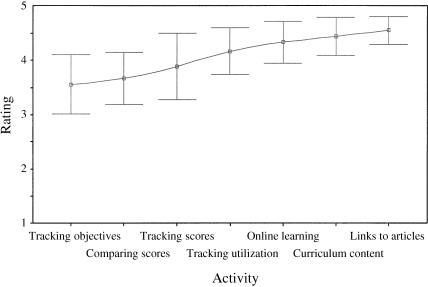

When comparing the features of an online curriculum with traditional curricular methods (i.e., lecture, syllabus), the most highly rated feature of the online curriculum was the ability to link to relevant articles (Fig. 3). Program directors also rated the ability to track individual utilization highly, as well as tracking group scores, and to compare these scores with other programs. Slightly less important was the ability to track scores on specific learning objectives. The overall rating of online learning as a means to improve ambulatory education was 4.22.

FIGURE 3.

Mean ratings of curriculum/website features. Program directors were asked to rate features of the website and curriculum on a Likert scale (1 = poor; 5 = excellent). Mean ratings for each aspect, with 95% confidence intervals, is shown.

When offered methods to improve the online curriculum (1 = strongly disagree; 3 = neutral; 5 = strongly agree), program directors felt that more module topics would improve the curriculum (mean rating, 3.91; SD, 1.04). However, program directors did not feel the site would be improved by adding their own content (mean, 2.74; SD, 1.18), nor did they feel that modules should be shortened (mean, 2.50; SD, 0.96) or lengthened (mean, 1.91; SD, 0.77). The majority of program directors (79%) thought utilization by house staff to be about what they expected or better than expected.

CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrated that the Internet can be used to distribute a curriculum in ambulatory care that appeals to a wide range of residency training programs. Rather than using the online curriculum as a replacement for their curriculum, most programs used the online curriculum to enhance aspects of their own educational program. Participation in the curriculum varied widely; mandatory programs saw significantly higher utilization than did voluntary programs. However, use in mandatory programs averaged less than 50%. Despite this, more than three-quarters of program directors felt that utilization was about what they expected or better. Use of the online curriculum was associated with improved knowledge. Program directors rated the online curriculum highly, particularly its content and the ability to link directly to references (a feature available in online reference tools such as UpToDate, but not possible with other educational innovations such as video conferencing). Program directors felt the Internet was a valuable tool for educating house staff. Although program directors wanted greater choice in curricular topics, they did not want to provide their own content.

Financial pressures facing residency training programs and increasing need for documentation and evaluation provide impetus for more collaborative efforts in education and evaluation; the Internet is ideal for this. Development and maintenance of curricula and computer technologies to support them requires substantial resources, and may be beyond the means of some residency training programs.10 By charging a fee to participating residency training programs, we have created a support structure to share these expenses and sustain the viability of the website, without resorting to pharmaceutical or other industry donations. Three years after the initial offering of this curriculum, 22 of the 24 original residency programs remain active users of the curriculum, and have been joined by an additional 25 programs.

The use of the Internet as a resource for medical education has grown rapidly, and has been used to educate medical students, house staff, and practicing physicians.11–19 Our curricular website differs from others in several important ways, having been structured to support both individual and institutional needs. While didactics target the individual learner, evaluative tools target institutional needs required by the ACGME. These evaluative tools were rated highly by residency program directors.

There are several limitations to this study. Curricular content was provided by a single institution, potentially representing a single approach to topics in ambulatory care. Individual success with learning objectives was not measured. Individual scores were masked from program directors because house staff at Johns Hopkins Hospital had cited lack of confidentiality as a barrier to website use early in its development. Also not measured was long-term knowledge retention. While an end-of-year posttest was offered to measure long-term knowledge retention, utilization was minimal. Finally, as in most educational research, there is no evidence that this curriculum will lead to improved patient care.

A rigorously designed, needs-based curriculum can be disseminated via the Internet, offering educational and evaluative tools that have broad appeal across residency training programs. The Internet offers the potential for significant collaboration and cost savings in medical education, as well as a tool for measuring educational interventions across training programs.

Authors’ note: Interested parties may sample the curricular website by directing their browser to http://www.hopkinsilc.org, and registering for the ambulatory care curriculum as a member of the “demonstration group.” Further instructions are contained within the website.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the module authors for their contribution to the content of this curriculum. We also thank the individual program directors who incorporated this curriculum into their education program. We are especially thankful to Dr. John Flynn, whose early and consistent support resulted in the success of this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education. Program Requirements for Residency Education in Internal Medicine. 2001. July. Available at http://www.acgme.org. Accessed April 9, 2003.

- 2.Harden RM, Hart IR. An international virtual medical school (IVIMEDS): the future of medical education? Med Teach. 2002;24:261–7. doi: 10.1080/01421590220141008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brotherton SE, Simon FA, Etzel SI. US graduate medical education, 2000–2001. JAMA. 2001;286:1056–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.9.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas PA. Medical education curricula: where's the beef? J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:449–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.05079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Candler CS, Uijtdehaage SHJ, Dennis SE. Introducing HEAL: the Health Education Assets Library. Acad Med. 2003;78:249–53. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharel M, Jain J, Hollander H. Comprehensive ambulatory medicine training for categorical internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:288–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Education Group for Guidelines on Evaluation. Guidelines for evaluating papers on educational interventions. BMJ. 1999;318:1265–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kern DE, Thomas PA, Howard DM, Bass EB. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-step Approach. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1995 Summary. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1997. p. 286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitcomb ME. The information technology age is dawning for medical education. Acad Med. 2003;78:247–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs J, Caudell T, Wilks D, et al. Integration of advanced technologies to enhance problem-based learning over distance: project TOUCH. Anat Rec. 2003;270B:16–22. doi: 10.1002/ar.b.10003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumlin KM, Bessette MJ, Lewis C, Richardson L. EMCyberSchool: an evaluation of computer-assisted instruction on the Internet. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:959–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris JM, Salasche SJ, Harris RB. The Internet and the globalisation of medical education. BMJ. 2001;323:1106. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7321.1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kemper KJ, Amata-Kynvi A, Sanghavi D, et al. Randomized trial of an Internet curriculum on herbs and other dietary supplements for health care professionals. Acad Med. 2002;77:882–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200209000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hege I, Radon K, Dugas M, Scharrer E, Nowak D. Web-based training in occupational medicine. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2003;76:50–4. doi: 10.1007/s00420-002-0376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de la Vega FM, Giegerich R, Fuellen G. Distance education through the Internet: the GNA-VSNS biocomputing course. Pac Symp Biocomput. 1996:203–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graeber S, Feldmann U. Medical information processing: an interactive course for the Internet. Int J Med Inf. 1998;50:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(98)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tello R, Davison BD, Blickman JG. The virtual course: delivery of live and recorded continuing medical education material over the Internet. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1519–21. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.6.1741519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orgill DP, Neuwalder JM, Arch M, Orgill J, Demling R. The development of an educational web site for burn care: burnsurgery.org. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2002;23:216–9. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200205000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]