Abstract

We describe a specific mentoring approach in an academic general internal medicine setting by audiotaping and transcribing all mentoring sessions in the year. In advance, the mentor recorded his model. During the year, the mentee kept a process journal.

Qualitative analysis revealed development of an intimate relationship based on empathy, trust, and honesty. The mentor's model was explicitly intended to develop independence, initiative, improved thinking, skills, and self-reflection. The mentor's methods included extensive and varied use of questioning, active listening, standard setting, and frequent feedback. During the mentoring, the mentee evolved as a teacher, enhanced the creativity in his teaching, and matured as a person. Specific accomplishments included a national workshop on professional writing, an innovative approach to inpatient attending, a new teaching skills curriculum for a residency program, and this study.

A mentoring model stressing safety, intimacy, honesty, setting of high standards, praxis, and detailed planning and feedback was associated with mentee excitement, personal and professional growth and development, concrete accomplishments, and a commitment to teaching.

Keywords: mentoring, qualitative analysis, career development, faculty development, medical education

“…almost nothing that brings me enjoyment…doesn’t hark back to…my mentors. They provided the forum for the exchange of ideas, and they provided the place to dream dreams and build visions.”1

—C. Everett Koop, MD

We admire mentors despite scant literature characterizing effective mentoring.2–5 Although mentoring is recommended for success in internal medicine,6 obstetrics and gynecology,7 family practice,8 surgery,9 and nursing,10 only 54 percent of junior faculty at 24 randomly selected U.S. medical schools identified recent mentoring.5 Inadequate mentoring disadvantages women and minorities in academic medicine.11 Mentored faculty rated their research skills and preparation higher than those unmentored.5 Successful family medicine researchers were mentored early in their careers.8 Senior university professors mentoring juniors improved productivity, satisfaction, and success.12

Only opinion and recollection underlie mentoring guidelines.4,9,15 Rare empirical studies of actual mentoring originate from higher education 13,16,17 and business,14 not from medicine.

To address this lack of clarity regarding the components of an effective mentoring relationship, we set out to systematically describe one successful mentoring experience.

METHODS

Subjects

The mentee (JR) was a 31-year-old general internist and the mentor (ML) was a 50-year-old professor of medicine, director of the primary care division and of the residency program from which JR graduated.

Data Collection and Analysis

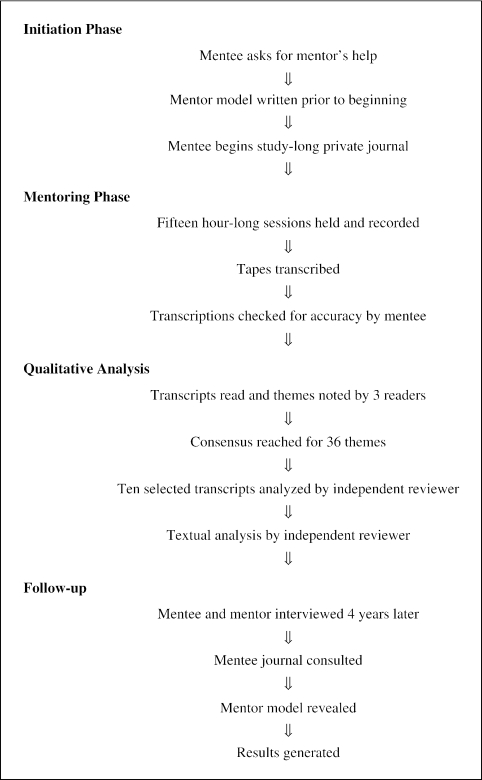

Figure 1 summarizes the flow of the project and the data set. All 15 mentoring sessions in 1 year were audiotaped and transcribed. Transcripts were checked against tapes for accuracy. In addition, ML wrote out his mentoring model (Table 1) and JR kept a journal about his experience. Four years after the last session, mentor and mentee reflected about the year in an analysis team-designed, semistructured interview.

FIGURE 1.

Study design.

Table 1.

The Mentor's Model

| Goals |

| 1. Be generative: stimulate. Stimulate a self-sustaining process of growth and individuation. |

| 2. Enhance the following skills: specificity, inner directedness, focus, problem solving, commitment to work, level of effort, creativity, and sense of self-efficacy. |

| Methods |

| 1. Craft the environment for safety, reliability, and regularity of meetings and procedures. |

| 2. Create an environment of empathy, reflection, mutual respect and affection, positive regard, genuineness, and congruence. |

| 3. Model how to work. |

| 4. Provide recurrent experiences of success and efficacy through graded activities at the level of the learner. Suggest new, more demanding activities. |

| 5. Give adequate support to ensure quality and success. |

| 6. Give adequate independence to ensure ownership and growth and a sense of personal achievement. |

| 7. Set ever higher and rigorous standards. |

| 8. Use a task orientation. Expect certain outcomes (we will accomplish specific things as follows…). |

| 9. Agree on meetings schedule, work expected. |

| 10. Use negotiated agenda setting, involvement of personal discussion, and focus on issues from the mentee. |

| 11. Include the expectation of unexpected positive outcomes (will accomplish remarkable, as yet unknown things). |

| Specific techniques |

| 1. Create a safe environment. |

| 2. Orient to tasks. |

| 3. Integrate use of knowledge, skills attitudes, and feelings in approaches to the work and to actual teaching. |

| 4. Expect independent work throughout. |

| 5. Repeatedly focus and raise insight and internalized standards. |

| 6. Negotiate agendas and approaches. |

| 7. Support risks and ventures at the least necessary level for success. |

| 8. Reframe failures as learning experiences. |

| 9. Attend to feelings about the work, about the relationship, and about the environment. |

| 10. Plan do, review, and revise cycles of work (praxis). |

| 11. Deal with problems in the relationship directly and early. |

| 12. Model teaching approaches in the mentoring itself. |

| 13. Sustain the relationship and the work after the core year. |

| 14. Be personally reflective, creative, and vulnerable. |

Three authors (ASR, AS, AK) independently coded the transcripts for themes and used an iterative consensus-building process to identify a common understanding of the salient aspects of the mentoring process and a set of important themes within the mentoring. A fourth analyst (MN) independently coded 10 randomly selected transcripts. The 2 sets of coding categories were compared to assess the trustworthiness of the initial analysis.

RESULTS

The qualitative analysts identified 4 salient aspects of the mentoring: meetings; themes; interactive qualities; and accomplishments.

The Mentoring Meetings

The fifteen 1-hour meetings had characteristic structure: a social opening; agenda negotiation; goal setting, and presentation and discussion of 2 to 3 topics. ML provided feedback, interpretation, and analysis. Sessions closed with a joint summary of issues covered and plans for the next 2 weeks. The mentor set the agenda for the first few sessions. JR took charge of a number of meetings, until, toward the end, they collaborated fluently on agenda setting. Regular meetings fostered the relationship.

JR's initial goal was to improve his teaching. Over time, the pair spent progressively more time refining this goal into achievable, specific behavioral objectives. Early in the year, ML encouraged higher-order goals beyond JR's initial conception:

ML: I think you might think about trying to define some higher-level goals and what specifically you plan to teach. And then—it seems to me that that's a logical way to start, and adjust your method to those goals. Such as—

JR: Well, let me try—a higher-order goal would be—in terms of content—would be to—the resident would be able to have an improved sense of clinical reasoning.

ML: Well, again…—An improved sense is a little bit—

JR: Will have improved clinical reasoning—Will improve their clinical reasoning skills.

ML: Yeah, good, that's good. (Transcript)

Following agenda and goal setting, JR reported on teaching activities since the last meeting; on a few occasions ML had directly observed JR teach. Through questioning, ML helped JR to identify areas and define motivation for further performance improvement. For each mentee-initiated topic, ML asked clarifying questions. Frequently, he encouraged discussion of the personal meaning of the topic or experience.

JR struggled with the courage needed to face his inadequacies and to make effective changes. When ML had to cancel meetings, JR felt personally rejected.

Themes Identified in the Mentoring

The themes identified by the initial three readers (see Table 2) were largely comparable to those identified by the independent fourth reader. For example, 26 of 36 independent analyst's themes closely resembled themes in the original consensus analysis, while 10 appeared novel. Of the original analysis themes, only 18 closely resembled the independent analyst’s. The following are examples of the themes identified:

Table 2.

Themes of a Yearlong Mentoring of a Clinician-educator

| Content |

| Effective Education: |

| Adult learning theory |

| Learner-centered learning |

| Leadership Skills: |

| Managing conflict |

| Enhancing motivation |

| Giving feedback |

| Collaboration |

| Mentee's Personal Growth: |

| Managing time |

| Obtaining reliable feedback |

| Becoming a more sophisticated teacher |

| Tolerating the vulnerability needed to change |

| Retaining individuality/creativity in teaching |

| Mentee's Professional Growth and Skills: |

| Small group facilitation |

| Evaluating attending rounds |

| Lecturing |

| Resident-as-teacher/faculty development |

| Teaching the medical interview |

| Teaching at the bedside |

| Videotape review |

| Moderating a panel |

| Conducting research |

| Evolution of Mentor-Mentee Relationship: |

| Mentoring others |

| Process |

| Mentor: |

| Focuses the agenda |

| Guides the process of the meeting |

| Clarifies goals of mentee |

| Challenges the mentee to expand his goals |

| Tracks personal issues of the mentee, making links over time |

| Helps mentee clarify feelings |

| Provides information |

| Provides resources (references to others, secretarial support) |

| Provides feedback |

| Shares feelings honestly |

| Mentee: |

| Provides meetings content by telling stories (e.g., “this is what I’ve done”) |

| Values Demonstrated: |

| The relationship centers on the needs of the mentee |

| Commitment to resolve conflict |

| Honesty |

| Trust |

| Respect |

| Willingness to take risks |

| Explicit focus on the process and progress of the relationship |

| Growth over Time |

| As year progresses, mentor shares more personal issues, collaborates more. |

| Early, mentor listens, gives feedback. In the middle, they collaborate (logistics, action, agreement, project coordination); mentor becomes more active toward end. |

| Together they analyze shared experience, with mentor providing analysis early and later mentee doing this for himself. |

| They talk about their own mentoring process: |

| Mentor gives feedback about sessions, enjoyment, reflects on mentee's progress. |

| Mentee gives feedback on process, enjoyment, self-progress, but does not give feedback to mentor. |

| Mentee more self-reflective; mentor more process and other-reflective. |

The mentor clarifies goals of mentee by being direct and respectful, expressing emotions, permitting vulnerability, and by showing his feelings. The environment was made safe for self-exploration because ML modeled in his behavior trust, respect, and intimacy. He listened actively and carefully. He uncovered JR's underlying assumptions through careful probing, as in this exchange after JR had reviewed the written evaluations of his performance, collected from the resident team:

JR: I wonder how I can change the format of what I’m doing to get at more…feedback about how to teach.

ML: Do you have any ideas about that? As a teacher, what are you trying to accomplish? (Transcript)

The mentor challenges the mentee to expand his goals, gently guiding JR to be systematic, to educate himself, and to set clear goals:

I see my role in part as to…keep pushing—having you push toward deeper thinking, more effective process. (ML Transcript)

When managing conflict, they examined it, determined why the conflict occurred, and spoke explicitly about feelings. This occurred around a mutually planned teaching activity:

ML: Perhaps we should talk about the nature of collaboration on this project…(I) feel like you’d taken it over and excluded me….

JR: Well, I’m happy to hear this because I had no idea that what I did had that effect on you…. I don’t feel like I wanted to take control of the process. I felt like, in some way, you allowed me to become more involved …it seemed at that point to me that you encouraged my participation to whatever extent I wanted, which is—I mean, that is a great thing. (Transcript)

This discussion of the conflict about collaboration changed how JR viewed the relationship. He felt the power of acknowledging conflict and it helped to make the relationship better. Six weeks later, he reflected to the mentor:

I feel like I can be very honest with you…I think we worked that through satisfactorily. (Transcript)

Interactive and Personal Qualities

The Mentor.

As is clear from his model (Table 1), ML used interpersonal skills to foster professional and personal growth. This model evolved over 20 years and was influenced especially by George Engel, Louis Welt, Kerr White, and Carl and David Rogers. ML wrote the model at the beginning of the year of mentoring and did not reveal it to the mentee until the year was done and the analysts had finished their work. In addition to citing his experience and opinion, ML focused on JR's goals by explicitly fostering self-reflection.

When JR sought advice about how to mentor a medical student, ML shared his approach:

ML: I think it's an interesting challenge. I’ve done this…so many times…I sort of don’t think about it any more…. What I do is…treat the people as junior colleagues with some differences. I try to let them…formulate as much as they can. Talk with them about that and then fill in the blanks…where does he need help at the moment. Ask them to fill them in and discuss it next time. (Transcript)

The Mentee.

This mentee came to meetings prepared to present detailed and revealing accounts of teaching. He followed through on tasks and responded honestly to feedback. He became increasingly articulate and specific about his goals, insights, and progress. JR revealed his flaws so that feedback had impact, fostering the mentor's ability to interpret and critique his behavior. At midyear, JR told ML the impact of the mentoring:

“I was struck by…this high energy which I felt…. Maybe that is a measure of your standards—I mean what are the standards for you might have something to do with my sense of energy—if your role is to encourage my deepening of thought and my commitment to aggressive action. (Transcript)

Outcomes of the Mentoring

One most important outcome was articulated in JR's journal:

A transformation has happened. The transformation involves a relationship…and a personal change.… That transformation is essentially one of my skills as a teacher. (Journal)

This transformation was a deepened friendship and professional relationship between the two. The personal transformation for the mentee was the discovery of the value of reflection on his work, as well as identifying and strengthening his weaknesses. More concrete outcomes included teaching projects, an innovative approach to conducting and evaluating inpatient attending, a national meeting workshop, mentoring others, improved small group facilitation and lecturing skills, a resident-as-teacher curriculum, and this article.

In practical ways, ML provided JR with professional opportunities by providing research support and introductions to others who could be helpful.

ML's rewards included participating in another's growth and development; successful investment of time, energy, and resources in human capital; new, effective teaching programs for the institution; and collaborations. Four years later, ML viewed the relationship as “…A challenge, part of my job, increasing my own skills as I learn to be nurturing and generative…by delicacy, perceiving where the growth edge is, stretching learners, fostering intensity, diligence, effort.” (4-year postinterview)

JR felt the mentoring enabled him to address his goals, which were to focus on being a clinical teacher, beyond what he would have been able to do on his own:

“…He said I have the capacity to be either ‘nice and ok’… or on the other spectrum end, I could be a superlative faculty member…. I was jolted into thought and action.” (Journal)

This kind of direct challenge was a deliberate aspect of the mentor's model.

I thought that, by subjecting Joe's teaching process to regular scrutiny, setting standards high, it would invigorate him, cause him to invest more energy, reinforce him, have him feel supported. (4 years postinterview)

DISCUSSION

This case study describes in detail a mentoring relationship that resulted in significant professional growth. JR, with the mentor's help, improved his skills of self-reflection, goal and objective setting, program innovation, and evaluation. JR acquired new work habits, teaching methods, and approaches. He designed and delivered innovative curricula, and presented at national meetings about mentoring.

Others who have studied professional and personal growth have postulated that personal growth occurs when one experiences powerful events involving oneself or others, as part of a helping relationship, and reflects on them through introspection.20 Excellent teachers incorporated self-reflection about successes and failures into teaching and found reflection essential to professional development.21 In this mentoring relationship, both powerful experiences (inpatient attending, teaching residents, the intimate relationship itself) and helping relationships (JR with learners, the mentoring relationship) were examined and used to encourage reflection and therefore create change. As JR reflects in his journal: “The times Mack has explicitly challenged me (against mediocrity, against shortsightedness, against close-mindedness, keep me on track. What are my weaknesses? Where can I watch out for problems to occur?” (Journal)

This case study suggests to us, as two other studies of mentor-mentee pairs, that successful mentoring is less distinguished by innate personality than by supportive behaviors.16,17 To function either as a mentor or as a mentee involves parallel qualities of attending to the process of the relationship, managing conflict effectively, and “learn[ing] and [continuing] to be open to possibility.”19

The purpose was to explore and describe the complexity of one mentoring relationship experienced as meaningful by the participants. We used rigorous, iterative qualitative methods to maximize the trustworthiness of the inferences we made from the data.22 That the majority of the independent analyst's themes overlapped, confirms the validity of the original team's analysis. The fourth analyst's interpretation was used for this confirmation, not as primary data for the paper.

If, as D.J. Levinson postulated, “poor mentoring in early adulthood is the equivalent of poor parenting in childhood,”18 the future and health of general internal medicine could as a field depend on us understanding the phenomenon. Here, we present the first in-depth analysis of the mentoring process. No others have analyzed the text of mentoring meetings in medicine. This study adds empirical content to the current literature on mentoring, which is hindered by its lack of observational data. We propose that this study serve as a starting point to study many mentoring pairs. We encourage others to record and analyze their mentoring meetings. We predict that the skills of being a good mentor and a good mentee are measurable and that leaders will be able to use well-developed measures to help evaluate professional performance. We look forward to collaboration on national research on mentoring. We urge others to not only praise mentoring but to study it.

Acknowledgments

The authors enthusiastically thank David Kern, Linda Pinsky, Michael Yedidia, and Felice Aull for their careful reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions. We also thank Kay Williams for transcribing the audiotapes and Sarah Barnum and Ralph Colp for their loyal support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams J. My mentor, myself. Town and Country; August 1994.

- 2.Swazey JP, Anderson MS. Mentors, Advisors, and Role Models in Graduate and Professional Education. Association of Academic Health Centers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bland C, Schmitz CC. Characteristics of the successful researcher and implications for faculty development. J Med Educ. 1986;61:22–31. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barondess JA. On mentoring. J R Soc Med. 1997;90:347–9. doi: 10.1177/014107689709000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palepu A, Friedman RH, Barnett RC, et al. Junior faculty members’ mentoring relationships and their professional development in U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 1998;73:318–23. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199803000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levinson W, Branch WT, Jr, Kroenke K. Clinician-educators in academic medical centers: a two-part challenge. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:59–64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-1-199807010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sciscione AC, Colmorgen GHC, D’Alton ME. Factors affecting fellowship satisfaction, thesis completion and career direction among maternal-fetal medicine fellows. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:1023–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morzinski JA, Diehr S, Bower DJ, Simpson DE. A descriptive, cross-sectional study of formal mentoring for faculty. Fam Med. 1998;28:434–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunnington GL. The art of mentoring. Am J Surg. 1996;171:604–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(95)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spouse F. The effective mentor: a model for student-centered learning. Nurs Times. 1996;92:32–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler NE. Women mentors needed in academic medicine. West J Med. 1991;154:468–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron SW, Blackburn RT. Sponsorship and academic career success. J Higher Educ. 1981;52:369–77. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perna FM. Mentoring and career development among university faculty. J Educ. 1995;177:31–45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roche GR. Much ado about mentors. Harv Bus Rev. 1979:14–28. January-February. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shea G. Mentoring: A Practical Guide. Normal, Ill: Crisp Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkey K. Mentor pedagogy and student teacher professional development: a study of two mentoring relationships. Teaching and Teacher Education. 1998;14:657–70. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haggarty L. The use of content analysis to explore conversations between school teacher mentors and student teachers. Br Educ Res J. 1995;21:183–97. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levinson DJ. Seasons of a Man's Life. New York: Random House; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang CA, Lynch J. Mentoring: the tao of giving and receiving wisdom. New York: Harper Collins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kern DE, Wright SM, Lipkin MJ, et al. Personal growth in medical faculty: a qualitative study. West J Med. 2001;175:92–8. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.2.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinsky L, Monson D, Irby D. How excellent teachers are made: reflecting on success to improve teaching. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 1998;3:207–15. doi: 10.1023/A:1009749323352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inui T, Frankel R. Evaluating the quality of qualitative research: a proposal pro tem. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:485–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02598180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]