Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To 1) compare the number of articles published about prostate, colon, and breast cancer in popular magazines during the past 2 decades, and 2) evaluate the content of in-depth prostate and colon cancer screening articles identified from 1996 to 2001.

DESIGN

We used a searchable database to identify the number of prostate, colon, and breast cancer articles published in three magazines with the highest circulation from six categories. In addition, we performed a systematic review on the in-depth (≥2 pages) articles on prostate and colon cancer screening that appeared from 1996 through 2001.

RESULTS

Although the number of magazine articles on prostate and colon cancer published in the 1990s increased compared to the 1980s, the number of articles is approximately one third of breast cancer articles. There were 36 in-depth articles from 1996 to 2001 in which prostate or colon cancer screening were mentioned. Over 90% of the articles recommended screening. However, of those articles, only 76% (25/33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 58% to 89%) cited screening guidelines. The benefits of screening were mentioned in 89% (32/36; 95% CI, 74% to 97%) but the harms were only found in 58% (21/36; 95% CI, 41% to 75%). Only 28% (10/36; 95% CI, 14% to 45%) of the articles provided all the necessary information needed for the reader to make an informed decision.

CONCLUSIONS

In-depth articles about prostate and colon cancer in popular magazines do not appear as frequently as articles about breast cancer. The available articles on prostate and colon cancer screening often do not provide the information necessary for the reader to make an informed decision about screening.

Keywords: colon cancer, prostate cancer, screening tests

Ecological theories of health behavior suggest that an individual is influenced by environmental factors as well as personal attributes.1,2 These environmental factors may affect an individual's personal health behavior by changing cultural norms. The mass media plays a significant role in this regard by making it culturally acceptable and desirable to reduce high-risk behaviors and engage in healthy behaviors, including cancer screening.3–5 For instance, following the mass media coverage of President Reagan's colon cancer, the Cancer Information Service of the National Cancer Institute received a sharp increase in calls from the public.6 There was also a corresponding increase in the use of colon cancer detection tests.6 More recently, the number of colonoscopies performed increased after Katie Couric promoted colorectal cancer awareness.7 Unfortunately, the media's direct and indirect effects frequently lead to misperceptions about health conditions and may lead individuals to make uninformed health choices.8–10

Misperceptions about cancer and cancer screening can be documented from all media formats. Previous research on cancer coverage in the media, however, has focused mostly on popular magazines, a common source of medical information for the general public.11–16 Studies have primarily focused on women's magazines,12,14,17–21 documented that breast cancer is the site with the highest frequency of coverage12,17,18 with limited media coverage of other cancers, such as colon cancer17 and prostate cancer, and has demonstrated misconceptions due to incomplete or inaccurate health reporting.

Given the strong emphasis on breast cancer and breast cancer screening in popular magazines and having demonstrated misconceptions related to health reporting, we wondered how other cancer and cancer screening information was presented in popular, nationally distributed magazines and how the frequency of these messages compared with messages about breast cancer. We chose specifically to examine prostate and colon cancer screening because prostate and colon cancer are important causes of cancer-related morbidity and mortality, and because decisions about screening for prostate and colon cancer require patients to have accurate, balanced information. We also chose to examine these two cancers because of the uncertainty as to whether prostate cancer screening is effective and because of the low utilization of colon cancer screening despite strong evidence of its effectiveness.

METHODS

We performed a search of popular magazines to determine the number of breast, prostate, and colon cancer articles published from 1980 to 2001. We followed our search with a systematic content review of in-depth articles on prostate and colon cancer screening that appeared in popular magazines from 1996 through 2001. The articles were reviewed for their recommendation for screening and whether the information provided the reader was adequate for making an informed decision. Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab statistical software 2000 (version 13.1, State College, Pa), Minitab, Inc.

Magazine Selection

We searched the Magazine Publishers of America (MPA) website in April 2002 for the top 100 Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC) magazines. We included in our study the top three magazines in six categories (African-American, Men's, Women's, News, General, and Health) with circulations over one million. We required that each magazine included had to be in circulation prior to 1990, publish articles addressing health issues, and be searchable on the electronic database Infrotrac General Reference Center Gold. If three magazines did not have circulations of one million or more in a specific magazine category, we used the next highest circulation magazine in that category.

Cancer Article Identification

We searched the electronic database Infrotrac General Reference Center Gold for each of the 18 magazines included in this study from the year 1980 through 2001. The search terms used were: prostate, prostate cancer, prostate cancer screening, cancer screening and prostate, prostate-specific antigen, PSA, colon, colon cancer, colorectal cancer, colon cancer screening, cancer screening and colon, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, fecal occult blood test, FOBT, barium enema, breast, breast cancer, breast cancer screening, cancer screening and breast, breast self-examination, and mammography.

Comparison of Breast, Prostate, and Colon Cancer Articles

We examined abstracts from our searches to determine the total number of articles about breast, prostate, and colon cancer from 1980 through 2001. We excluded abstracts in which breast, prostate, or colon cancer was not the main focus (e.g., studies examining breast implants, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and colonic irrigation). To determine whether the number of articles reflected the prevalence of cancer and to determine the potential impact of the articles on the public, we plotted the total number of articles in each category graphically by year of publication. We also examined the proportion of articles from each of our six categories of magazines.

Content Analysis of Prostate and Colon Cancer Screening Articles

Each available prostate and colon cancer screening article from 1996 through 2001 was reviewed for length and focus of the article. Articles were considered in-depth articles if they were longer than two pages of typed text and either focused on prostate cancer or colon cancer, or discussed prostate or colon cancer more generally in an article about cancer. The page criterion was established because most magazine articles were less than one page and did not provide enough information. A review of each in-depth article (1996 to 2001) was performed for 30 content items in the following categories: 1) risk information, 2) presence and source of screening guidelines, and 3) potential benefits, harms, and alternatives to screening. We considered several items (potential harms, benefits, alternatives, and uncertainty) necessary for providing patients with sufficient information to make an informed decision.22–25 Other items were designed to detect potential biases in information presentation (format of risk presentation, presence of screening vignette) and identify what sources were used for health information (presence and source of screening guidelines). A single reviewer abstracted information from these articles; a second reader reevaluated 65% of the articles to test for reliability. Agreement between reviewers was good, with κ= 0.77.

RESULTS

Cancer Article Identification

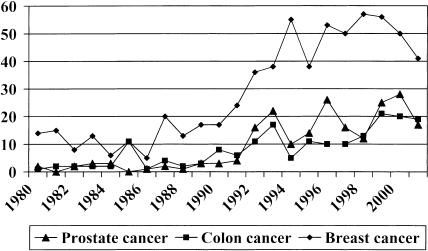

The 18 magazines meeting the inclusion criteria for this study are listed in Table 1. Sixteen magazines were in publication prior to 1980 and two magazines began publication in the 1980s (Shape in 1981 and Men's Health in 1988). The trend in the number of articles focusing on prostate, colon, and breast cancer from these magazines from 1980 through 2001 is displayed in Figure 1. The search identified a total of 210 prostate, 181 colon, and 637 breast cancer articles. From 1980 to 2001, there was an increase in the number of articles focusing on each type of cancer. The number of articles that focused on prostate and colon cancer, however, was dramatically less than the number of breast cancer articles. In addition, the distribution of the prostate and colon cancer articles by magazine type is shown in Figure 2. Both prostate and colon cancer articles appear in all categories of magazines, but there are more prostate than colon cancer articles in African-American, men's, and general magazines.

Table 1.

The Top Three Magazines with the Highest Circulation in Six Categories of Popular Magazines

| Type of Magazine | Magazine | Weekly (W) or Monthly (M) | Magazine Publishers of America Average Circulation 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|

| African American | 1. Ebony | M | 1,782,442* |

| 2. Essence | M | 1,052,068* | |

| 3. Jet | W | 965,204* | |

| Men's | 1. Men's Health | M | 1,659,505* |

| 2. Esquire | M | 583,653 | |

| 3. GQ | M | 573,992 | |

| Women's | 1. Better Homes & Garden | M | 7,603,006* |

| 2. Family Circle | M | 4,857,727* | |

| 3. Good Housekeeping | M | 4,531,082* | |

| News | 1. Time | W | 4,128,626* |

| 2. Newsweek | W | 3,254,513* | |

| 3. US News World & Report | W | 2,075,545* | |

| General | 1. Reader's Digest | M | 12,558,435* |

| 2. TV Guide | W | 9,259,455* | |

| 3. People | W | 3,714,268* | |

| Health | 1. Prevention | M | 3,115,991* |

| 2. Shape | M | 1,633,442* | |

| 3. Health | M (10 months) | 1,395,072* |

Top 100 magazine by circulation.

FIGURE 1.

Number of prostate, colon, and breast cancer articles in top circulation magazines, 1980 to 2001.

FIGURE 2.

Number of prostate and colon cancer articles by type of magazine, 1980 to 2001.

Content Analysis of Prostate and Colon Cancer Screening Articles

From 1996 to 2001, a total of 217 cancer articles (prostate, 124; colon, 93) were identified. We were able to locate all articles except three (all focused on colon cancer) by downloading the article from the Internet via the electronic search database or in local libraries. Forty articles (prostate, 26; colon, 14) fit the criteria for an in-depth article. Screening for colon or prostate cancer was mentioned in 36 of the 40 (90%) in-depth articles (prostate, 22; colon, 14). The content of these articles comprise the basis for this report. Of the 36 in-depth articles, the prostate cancer screening articles were distributed fairly evenly across magazine types, while 64% (9/14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 35% to 87%) of the in-depth colon cancer screening articles were published in women's magazines.

Screening Guidelines

Ninety-one percent (20/22; 95% CI, 71% to 99%) of the prostate and 93% (13/14; 95% CI, 66% to 99%) of the colon cancer screening articles recommended that individuals undergo screening. Of the prostate and colon cancer screening articles that recommended screening, 85% (17/20; 95% CI, 62% to 97%) and 62% (8/13; 95% CI, 32% to 86%) cited screening guidelines, respectively. The guidelines mentioned most often were those from the American Cancer Society (70%) and the American Urologic Association (12%). Less frequently cited were those of the National Cancer Institute (12%) and the U.S. Preventive Service Task Force (3%).

The screening test(s) mentioned most often in the prostate cancer screening articles was a combination of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and digital rectal examination in 77%. The screening tests mentioned most often for colon cancer screening articles were colonoscopy (86%), flexible sigmoidoscopy (71%), and fecal occult blood test (FOBT; 50%). When a screening test was mentioned in an article, the test procedure was explained in 86% (31/36; 95% CI, 71% to 95%) of the screening articles. A starting age for undergoing cancer screening was provided in 81% (29/36; 95% CI, 64% to 92%) of the screening articles; however, the issue of stopping screening was addressed in only three prostate cancer screening articles. Additionally, only 55% (12/22; 95% CI, 32% to 76%) of the in-depth articles on prostate cancer screening and 79% (11/14; 95% CI, 49% to 95%) of the in-depth articles on colon cancer screening provided information regarding risk factors that might prompt screening at an earlier age.

Potential Screening Benefits and Harms

The benefits of screening were provided in 89% (32/36; 95% CI, 74% to 97%) of the cancer screening articles (Table 2). Early detection of the cancer disease process was the benefit mentioned most often in the articles. The potential harms of screening were listed in 58% (15/22; 95% CI, 45% to 86%) of the prostate cancer screening and in 43% (6/14; 95% CI, 18% to 71%) of the colon cancer screening articles (Table 3). Uncertainty about the benefits of undergoing cancer screening was mentioned in 46% (10/22; 95% CI, 24% to 68%) of the prostate cancer screening articles and in none of the colon cancer screening articles.

Table 2.

Benefits of Cancer Screening

| Benefit | Prostate N = 22 n (%) | Colon N = 14 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Early detection | 14 (64) | 11 (79) |

| Cure disease | 11 (50) | 7 (50) |

| Saves lives | 10 (46) | 8 (57) |

| Chance for effective treatment | 7 (32) | 2 (14) |

| Prevention of cancer | 0 | 10 (71) |

| Improved quality of life | 0 | 1 (7) |

| Decrease risk of cancer | 0 | 1 (7) |

| Saves money | 0 | 1 (7) |

| Total | 19 (86) | 13 (93) |

Table 3.

Potential Harms Associated with Cancer Screening

| Harms | Prostate N = 22 n (%) | Colon N = 14 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Test results: false positive | 9 (41) | 2 (14) |

| Test results: false negative | 3(14) | 2(14) |

| Unnecessary treatment | 7 (32) | 0 |

| Unnecessary tests | 3 (14) | 0 |

| Unnecessary anxiety | 2 (9) | 0 |

| Slow growing or non-life threatening | 2 (9) | 0 |

| Gives misleading results | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Questionable if saves lives | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Perforation | 0 | 5 (36) |

| Hemorrhage | 0 | 2 (14) |

| Death | 0 | 2 (14) |

| Impotence | 15 (68) | 0 |

| Incontinence | 15 (68) | 0 |

| Total | 15 (68) | 6 (43) |

Alternatives to Screening

Alternatives to screening were mentioned in 32% (7/22; 95% CI, 14% to 55%) of the prostate cancer screening articles and in 77% (11/14; 95% CI, 49% to 95%) of the colon cancer screening articles. The most frequently mentioned alternatives were a change in diet (17 articles), increasing exercise (10 articles), and the use of various supplements (10 articles). Not screening was never given as an option for colon cancer. Several articles (46%) acknowledged the uncertainties associated with prostate cancer screening.

Vignettes/Public Figures

The use of vignettes is a popular narrative technique to draw the reader to the magazine article. In this study, a vignette was defined as a testimonial about undergoing a cancer screening test described by a specific person. We identified vignettes in 56% (20/36; 95% CI, 38% to 72%) of the in-depth cancer screening magazine articles. A famous personality was featured in 56% (20/36; 95% CI, 38% to 72%) of the in-depth cancer screening articles, a technique that may have important effects on subsequent public behavior.6,26 Personalities mentioned most often were in politics 42% (15/36; 95% CI, 26% to 59%), sports 17% (6/36; 95% CI, 6% to 33%), or the media 14% (5/36; 95% CI, 5% to 30%).

Risk Information

Each cancer screening article was evaluated to determine whether benefit and harm information was provided in the form of absolute, relative, or comparative risk. Absolute risk information was provided in 64% (23/36; 95% CI, 46% to 79%), relative risk in 92% (33/36; 95% CI, 78% to 98%), and comparative risk in 47% (17/36; 95% CI, 30% to 65%) of the cancer screening articles. When presented as comparative risk, the likelihood of acquiring prostate and colon cancer was compared most often to breast and lung cancer.

Informed Decision Making

To make an informed decision about undergoing cancer screening, an individual should know the potential benefits, harms, alternatives, and uncertainties (prostate) of undergoing a test.22–25 Of the 36 in-depth articles (Table 4), only 28% (10/36; 95% CI, 14% to 45%) of the cancer screening articles provided all of the necessary elements of information needed for the reader to make an informed decision.

Table 4.

Factors in Making an Informed Decision

| Magazine Type | Number of Articles | Focus of Articles: Prostate/Colon | Screening Benefits | Screening Harms | Screening Alternatives | Screening Uncertainty (Prostate Articles Only) | Informed Decision Making |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American | 5 | 5/0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Men's | 5 | 4/1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Women's | 12 | 3/9 | 11 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| News | 6 | 4/2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| General | 4 | 4/0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Health | 4 | 2/2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

DISCUSSION

Our study documents that the number of magazine articles dedicated to prostate and colon cancer was approximately one third of the number that focused on breast cancer in popular magazines during the years 1980 through 2001. Furthermore, during the 6 years from 1996 through 2001, only 17% (36/217; 95% CI, 12% to 22%) of the total prostate and colon cancer articles were in-depth or comprehensive articles that discussed screening. Only 28% (10/36; 95% CI, 14% to 45%) of these articles provided the reader with the information necessary to make an informed decision about undergoing a cancer screening test. Some key points missing from many of the articles were 1) the relative importance of the various cancer risk factors, 2) the risk factors that should lead to earlier screening, 3) the issue of when to consider stopping screening, and 4) the potential harms, complications, and uncertainties associated with a screening test. This information is important because exposure to cancer screening messages have been shown by other investigators to change the public's knowledge about cancer and opportunities for prevention.6,15,27,28

Our findings may explain part of the public's misperception about the risk of different types of cancer. For example, the low awareness of the importance of screening for colon cancer and the low awareness of the controversies about prostate cancer screening may result from the low relative frequency with which these topics are discussed in popular magazines, particularly when compared to breast cancer. It is also notable that messages about colon cancer screening may not be reaching males and African Americans who are reading only magazines geared at their specific populations.

Our findings may also explain the public's misperception about the effectiveness of screening. Articles not only failed to discuss the uncertainty about the benefits of prostate cancer screening, but failed to state the known benefits of colon cancer screening. For example, approximately 46% of articles about prostate cancer screening suggested that screening would save lives, while only 57% stated that colon cancer screening would save lives.

The mass media, in the form of popular magazines, has the opportunity to reach many people. The frequency and content of the cancer communications in magazines can make messages about certain cancer screenings more prominent, and they may also be adapted to target the needs of specific population groups. We agree with others who have said3,10,14,29–32 that for magazine articles to accurately inform readers about cancer screening, they should cite sources for their information, provide additional resources for the reader, present both sides of any controversy associated with the screening test, offer the health information without news framing, and use vignettes which adequately represent the population in whom screening is most appropriate. Although magazine articles may be intended to raise awareness and not fully inform patients about screening, magazines may provide the only opportunity to correct misperception among the many individuals who do not raise screening issues with their physicians but access screening tests directly through health fairs, mass community screenings, or in-home testing. Therefore, it is important that popular magazines provide accurate, balanced, and sufficient information in these articles. Providing the authors of these articles with training in basic epidemiology and biostatistics could help place cancer information in the appropriate perspective.

Although we've raised several concerns, we must acknowledge the limits in our analysis. First, although we included magazines with high readership, we do not know how many people actually read the actual articles about cancer or get their information indirectly from their relatives or friends. In this study, we included articles from women's magazines because men may get the information directly from reading the articles or indirectly via the women in their lives. Second, the content of articles that were short in length was not reviewed. The brief article or paragraph found in most magazines may also impact on an individual's risk perception and their cancer screening practices, but will not likely provide the reader with adequate information for an informed choice as we have previously noted.

CONCLUSION

Despite the limitations, we feel our study has made an important contribution by addressing the coverage of prostate and colon cancer screening information that is found in popular magazines. Relatively few popular magazine articles provided in-depth information about prostate and colon cancer screening. In addition, few articles provided the reader with enough information for informed decision making. This lack of information may help to explain the low awareness of the importance of colon cancer screening and the lack of appreciation of the pros and cons associated with prostate cancer screening. The media and cancer prevention experts should collaborate to provide accurate and comprehensive cancer information to the general public.

REFERENCES

- 1.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stokols D. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments. Toward a social ecology of health promotion. Am Psychol. 1992;47:6–22. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arkin EB. Opportunities for improving the nation's health through collaboration with the mass media. Public Health Rep. 1990;105:219–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanovitzky I, Blitz CL. Effect of media coverage and physician advice on utilization of breast cancer screening by women 40 years and older. J Health Commun. 2000;5:117–34. doi: 10.1080/108107300406857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen DA, Scribner RA, Farley TA. A structural model of health behavior: a pragmatic approach to explain and influence health behaviors at the population level. Prev Med. 2000;30:146–54. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown ML, Potosky AL. The presidential effect: the public health response to media coverage about Ronald Reagan's colon cancer episode. Public Opin Q. 1990;54:317–29. doi: 10.1086/269209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cram P, Fendrick AM, Inadomi J, Cowen ME, Carpenter D, Vijan S. The impact of a celebrity promotional campaign on the use of colon cancer screening: the Katie Couric effect. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1601–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost K, Rank E, Maibach E. Relative risk in the news media: a quantification of misrepresentation. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:842–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.5.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeaton WH, Smith D, Rogers K. Evaluating understanding of popular press reports of health research. Health Educ Q. 1990;17:223–34. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke W, Olsen AH, Pinsky LE, Reynolds SE, Press NA. Misleading presentation of breast cancer in popular magazines. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Health Council. Americans Talk About Science and Medical News: The National Health Council Report. New York, NY: Roper Starch Worldwide; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerlach KK, Marino C, Hoffman-Goetz L. Cancer coverage in women's magazines: what information are women receiving? J Cancer Educ. 1997;12:240–4. doi: 10.1080/08858199709528496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlsson M. Cancer patients seeking information from sources outside the health care system. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:453–7. doi: 10.1007/s005200000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moyer CA, Vishnu LO, Sonnad SS. Providing health information to women. The role of magazines. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2001;17:137–45. doi: 10.1017/s0266462301104125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meissner HI, Potosky AL, Convissor R. How sources of health information relate to knowledge and use of cancer screening exams. J Community Health. 1992;17:153–65. doi: 10.1007/BF01324404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson JD, Meischke H. Women's preferences for cancer-related information from specific types of mass media. Health Care Women Int. 1994;15:23–30. doi: 10.1080/07399339409516091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerlach KK, Marino C, Weed DL, Hoffman-Goetz L. Lack of colon cancer coverage in seven women's magazines. Women Health. 1997;26:57–68. doi: 10.1300/j013v26n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman-Goetz L, MacDonald M. Cancer coverage in mass-circulating Canadian women's magazines. Can J Public Health. 1999;90:55–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03404101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman-Goetz L, Gerlach KK, Marino C, Mills SL. Cancer coverage and tobacco advertising in African-American women's popular magazines. J Community Health. 1997;22:261–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1025100419474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman-Goetz L. Cancer experiences of African-American women as portrayed in popular mass magazines. Psychooncology. 1999;8:36–45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199901/02)8:1<36::AID-PON330>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marino C, Grelach KK. An analysis of breast cancer coverage in selected women's magazines, 1987–1995. Am J Health Promot. 1999;13:163–70. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-13.3.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braddock CH, III, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA. 1999;282:2313–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pignone M, Rich M, Teutsch SM, Berg AO, Lohr KN. Screening for colorectal cancer in adults at average risk: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:132–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris R, Lohr KN. Screening for prostate cancer: an update of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Service Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:917–29. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan ECY, Vernon SW, Haynes MC, O'Donnell FT, Ahn C. Physician perspectives on the importance of facts men ought to know about prostate-specific antigen testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:350–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lane DS, Polednak AP, Burg MA. The impact of media coverage of Nancy Reagan's experience on breast cancer screening. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1551–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.11.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanchard D, Erblich J, Montgomery GH, Bovbjerg DH. Read all about it: the over-representation of breast cancer in popular magazines. Prev Med. 2002;35:343–8. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dobias KS, Moyer CA, McAchran SE, Katz SJ, Sonnad SS. Mammography messages in popular media: implications for patient expectations and shared clinical decision-making. Health Expect. 2001;4:127–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2001.00120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson T. Stattuck lecture—medicine and the media. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:87–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brody JE. Communicating cancer risk in print journalism. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1999;25:170–2. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Malley AS, Kerner JF, Johnson L. Are we getting the message out to all? Health information sources and ethnicity. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17:198–202. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ubel PA, Jepson C, Baron J. The inclusion of patient testimonials in decision aids: effects on treatment choices. Med Dec Making. 2001;21:60–8. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]