Abstract

Ritonavir (RTV) strongly increases the concentrations of protease inhibitors (PIs) in plasma in patients given a combination of RTV and another PI. This pharmacological interaction is complex and poorly characterized and shows marked inter- and intraindividual variations. In addition, RTV interacts differently with saquinavir (SQV), indinavir (IDV), amprenavir (APV), and lopinavir (LPV). In this retrospective study on 542 human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients, we compared inter- and intraindividual variability of plasma PI concentrations and correlations between the Cmin (minimum concentration of drug in plasma) values for RTV and the coadministered PI Cmin values. Mean RTV Cmins are significantly lower in patients receiving combinations containing APV or LPV than in combinations with SQV or IDV. With the most common PI dose regimens (600 mg of IDV twice a day [BID], 800 mg of SQV BID, and 400 mg of LPV BID), the interindividual Cmin variability of patients treated with a PI and RTV seemed to be lower with APV and LPV than with IDV and SQV. As regards intraindividual variability, APV also differed from the other PIs, exhibiting lower Cmin variability than with the other combinations. Significant positive correlations between RTV Cmin and boosted PI Cmin were observed with IDV, SQV, and LPV, but not with APV. Individual dose adjustments must take into account the specificity the pharmacological interaction of each RTV/PI combination and the large inter- and intraindividual variability of plasma PI levels to avoid suboptimal plasma drug concentrations which may lead to treatment failure and too high concentrations which may induce toxicity and therefore reduce patient compliance.

Ritonavir (RTV), a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitor (PI), is relatively poorly tolerated at the full dose (600 mg twice a day [BID]) and has a potent inhibitory effect on the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A, the major enzyme responsible for the metabolism of the PIs and many other drugs, in the intestinal wall and liver. RTV also inhibits P-glycoprotein transport, which may increase the absorption of PIs by this pathway. Even at a reduced dose, RTV strongly increases the plasma drug concentrations of other PIs administered concomitantly (10).

This property of RTV in which it strongly increases the concentrations of other PIs is exploited therapeutically: low-dose RTV is increasingly used to improve the pharmacokinetic profiles of other PIs by ensuring higher and more stable plasma drug concentrations, while at the same reducing the number of daily doses and the number of tablets or capsules in each dose and sometimes avoiding the effect of food on drug absorption (11).

These pharmacological interactions are complex and poorly characterized and show marked interindividual variations (1). In addition, RTV interacts differently with saquinavir (SQV), indinavir (IDV), amprenavir (APV), and lopinavir (LPV).

Precise individual tailoring of the dose regimens of these PI combinations is crucial to avoid subtherapeutic plasma drug concentrations (which are predictive of virologic breakthrough) and excessively high concentrations (which may induce toxicity and therefore reduce patient compliance) (1-3, 11, 13).

In this study of patients receiving various PIs in combination with RTV, we compared the pharmacological interactions of the different dual-PI regimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective study involved HIV-infected patients managed in the infectious diseases department of St. Antoine and Tenon hospitals (Paris, France) from September 1999 to August 2002. They were treated with RTV (100 mg BID) (“baby dose”) in combination with SQV (600 to 800 mg BID), IDV (400 to 800 mg BID), APV (600 mg BID), or LPV (400 mg BID). Patients receiving combinations of more than two PIs (salvage therapy) were excluded from the study, as were those receiving nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (owing to their interactions with PIs). If patients had received successive PI/RTV dual combinations and undergone successive drug determinations during the study period, only the pharmacological data collected for the first PI/RTV dual combination were used in this study in order to preserve statistical independence between the groups in the interindividual variability analysis.

When several drug assays were done in a given patient receiving the same PI combination at the same doses, only the initial values were used for the analysis of interindividual variability. The analysis of intraindividual variability was exclusively based on values obtained in a given patient receiving the same PI combination at the same doses at each assay.

Patients who forgot to take at least one drug dose during the two days prior to the pharmacological assay were not included in the analysis. The nurse who performed the blood test asked patients about their compliance, and information was based on patients' answers. Only plasma PI concentrations measured 12 ± 2 h after the last administration (minimum concentration of drug in plasma [Cmin]) were taken into account in patients receiving a stable antiretroviral drug regimen for at least 2 weeks before blood sampling.

These RTV and PI concentrations in plasma were determined by high-pressure liquid chromatography with quantification cutoffs of 5 ng/ml for APV and IDV and 10 ng/ml for LPV, SQV, and RTV (15).

Data were analyzed using nonparametric tests (Yates' and Fisher's chi-squared tests and the Mann-Whitney test); only series of assays performed on samples from at least 10 subjects were used for the analysis of interindividual variability. Correlations between the RTV Cmins and the PI Cmins were determined by linear regression curves.

RESULTS

A total of 955 plasma PI determinations were done during the 36-month study period in 542 patients. A total of 413 patients received low-dose RTV (100 mg BID) combined with another PI. The other 129 patients received only one PI (APV, IDV, or nelfinavir [NFV]) and were studied for comparison.

Interindividual variability of plasma RTV concentrations.

RTV Cmins in the patients who were also receiving another PI showed large interindividual variability, regardless of the combination. The calculated coefficients of variation of RTV Cmins observed with each RTV/PI combination were generally high (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Interindividual variability of RTV and PI Cmins

| Treatmenta | n | PI

|

RTV

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Cmin (ng/ml) | SD (ng/ml) | CVb (%) | Mean Cmin (ng/ml) | SD (ng/ml) | CV (%) | ||

| APV | |||||||

| 1,200/0 | 10 | 300 | 185 | 61.6 | |||

| 600/100 | 58 | 1,756 | 791 | 45.0 | 142 | 85 | 59.9 |

| IDV | |||||||

| 800/0 TID | 29 | 361 | 659 | 182.6 | |||

| 800/100 | 104 | 1,267 | 999 | 78.8 | 551 | 526 | 95.3 |

| 600/100 | 97 | 855 | 787 | 92.0 | 562 | 428 | 76.1 |

| 400/100 | 40 | 571 | 437 | 76.5 | 568 | 407 | 71.7 |

| NFV | |||||||

| 1,250/0 | 90 | 1,841 | 1,275 | 69.3 | |||

| 1,250/100 | 11 | 3,385 | 2,525 | 74.6 | 308 | 307 | 99.9 |

| SQV | |||||||

| 800/100 | 40 | 792 | 842 | 106.4 | 599 | 467 | 77.9 |

| 600/100 | 18 | 620 | 519 | 83.7 | 500 | 354 | 70.8 |

| LPV, 400/100 | 45 | 4,650 | 2,398 | 51.6 | 200 | 115 | 57.4 |

The PI/RTV treatment is shown with the PI dose (APV, IDV, NFV, SQV, or LPV) before the slash and the RTV dose after the slash. Both doses are given in milligrams, and the drugs were administered BID unless stated otherwise.

CV, coefficient of variation.

Using a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, distributions of RTV Cmins are globally different between the groups (P < 0.0001). Distributions are not statistically different, however, between the three IDV/RTV groups (P = 0.45 by the Kruskal-Wallis test) and between the two SQV/RTV groups (P = 0.55 by the Mann-Whitney test) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of mean RTV Cmins of RTV/PI combinations by the Mann-Whitney test

| RTV/PI treatment |

P valuea

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| RTV/SQV | RTV/IDV | RTV/APV | |

| RTV/SQV | 0.55b | ||

| RTV/IDV | 0.697 | 0.425c | |

| RTV/APV | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| RTV/LPV | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.009 |

P value in comparison of mean RTV Cmins of RTV/PI combinations.

Between SQV dose regimens (800 mg BID and 600 mg BID).

Between IDV dose regimens (800 mg BID, 600 mg BID, and 400 mg BID) by the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Using the Mann-Whitney test, mean RTV Cmins in the patients receiving SQV or IDV were not statistically different (P = 0.697). In contrast, mean RTV Cmins were significantly lower in patients receiving APV or LPV than in those receiving SQV or IDV (Tables 1 and 2). The coefficients of variation of mean RTV Cmins were generally large, close to 60% in patients receiving APV or LPV and from 71 to 100% in those receiving SQV or IDV (Table 1). Mean RTV Cmins were statistically lower in the patients who were receiving APV or LPV than in the other RTV/PI combinations (P = 0.009 by the Mann-Whitney test) (Table 2).

Therefore, SQV and IDV behaved differently from APV and LPV in their influence on RTV Cmins following a regimen of 100 mg of RTV BID.

Interindividual variability of plasma drug concentrations of the PI combined with RTV.

The interindividual variability of Cmins observed in patients receiving IDV, NFV, and APV without RTV was shown for comparison in Table 1 as the Cmin coefficients of variation. The variability of the three drugs was established in groups of different sizes (29, 10, and 90 patients, respectively), but the values are in keeping with those reported elsewhere (4, 5, 16). The interindividual variability of Cmin was higher following administration of IDV (coefficient of variation, 182.6%) than with NFV or APV (coefficient of variation, 69.3 and 61.6%, respectively).

As shown by the comparison of mean Cmins of IDV and APV administered with and without RTV, the use of RTV as a pharmacological booster resulted in a significant increase in the plasma PI concentrations. Combining APV with RTV multiplies the mean APV Cmin by a factor of 5.5 while allowing the APV dose to be halved. The mean IDV Cmin was increased by a factor of 2.5 in combination with RTV, despite a decrease in the IDV dose from 2,400 mg/day (three times a day) to 1,200 mg/day (BID). The booster effect of RTV on NFV was weaker (<2 with the same NFV doses) (Table 1).

However, the interindividual variability of the Cmins of each PI remained large despite concomitant RTV administration (coefficient of variation, 45.0 to 106.4%). There was no marked differences in the interindividual variability of the Cmins between the different dosage regimens when IDV was combined with RTV (coefficient of variation, 76.5 to 92.0%). When SQV was combined with RTV, the coefficient of variation of the Cmins ranged from 83.7% (600 mg BID regimen) to 107.6% (800 mg BID regimen) (Table 1).

The analysis also suggests that the interindividual variability of Cmins of the PIs combined with RTV was lower in the case of APV and LPV (45.3 and 50.8%, respectively) than with IDV and SQV (76.4 to 91.4% and 83.7 to 107.6%, respectively) (Table 1).

Intraindividual variability.

Cmins of RTV/PI combinations were sometimes determined again in order to control the stability of the pharmacological interaction in the different combinations. A median of three plasma PI measurements (range, two to six) were done in 132 patients during identical dose regimens (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Intraindividual variability of PI and RTV Cmins

| Treatmenta | n | PI

|

RTV

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean CVb (%) | SD (%) | Mean CV (%) | SD (%) | ||

| APV, 600/100 | 11 | 37.5 | 20.4 | 58.0 | 33.4 |

| IDV | |||||

| 800/100 | 14 | 55.1 | 34.7 | 45.2 | 39.5 |

| 600/100 | 31 | 52.5 | 32.5 | 45.5 | 30.4 |

| 400/100 | 18 | 28.4 | 23.4 | 21.9 | 17.8 |

| LPV, 400/100 | 20 | 42.5 | 27.9 | 39.9 | 22.3 |

| SQV | |||||

| 800/100 | 7 | 61.4 | 29.0 | 75.8 | 52.8 |

| 600/100 | 5 | 53.2 | 22.3 | 37.3 | 37.3 |

| NFV, 1,250/0 | 26 | 50.1 | 31.2 | ||

The PI/RTV treatment is shown with the PI dose (APV, IDV, LPV, SQV, or NFV) before the slash and the RTV dose after the slash. Both doses are given in milligrams, and the drugs were administered BID.

CV, coefficient of variation.

The intraindividual variability of the Cmins of RTV and PI was expressed in terms of coefficient of variation, calculated from the weighted means of drug determinations performed for each patient. Table 3 shows the mean coefficients of variation and standard deviations for RTV and PI Cmins for patients given RTV/PI combinations. This intraindividual variability of Cmins was relatively large, as the coefficients of variation of mean values observed ranged from 28.4 to 61.4% for the PI and 21.9 to 75.8% for RTV. As shown by the comparison of coefficients of variation of mean values, the intraindividual variabilities of RTV and PI Cmins are similar. Globally, the observed values were similar to those obtained in the 26 patients treated with NFV without RTV. For the IDV/RTV combination, we observed a difference in the coefficients of variation of means according to the IDV dose prescribed (>50% for 800-mg IDV BID and 600-mg IDV BID regimens and <30% for 400-mg IDV BID regimen).

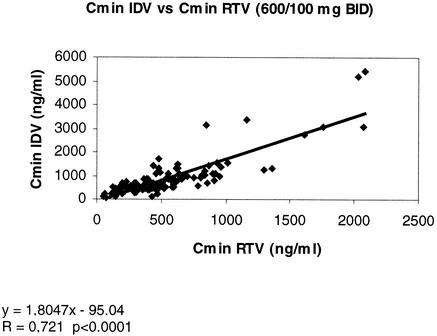

Correlations between Cmins of RTV and PI in patients given different RTV/PI combinations. (i) IDV and RTV.

In patients given the IDV/RTV combination, the Cmins of RTV correlated with those of IDV: the higher the RTV Cmin, the higher the IDV Cmin (correlation coefficient [r] = 0.72 and P < 0.0001 for the combination of RTV [100 mg] and IDV [600 mg], both drugs given BID) (Fig. 1). The same correlation was found with the other IDV dose regimens (800 and 400 mg BID).

FIG. 1.

Correlation between the Cmins for IDV (600 mg BID regimen) and RTV (100 mg BID).

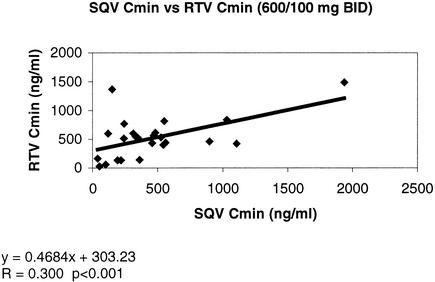

(ii) SQV and RTV.

In patients given the SQV/RTV combination, the Cmins of SQV and RTV correlated in the same way as the IDV/RTV combination. The Cmins of RTV and SQV correlated with each other, despite a wider dispersion of the results (r = 0.30 and P < 0.001 for the combination of RTV [100 mg] and SQV [600 mg], both given BID) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Correlation between Cmins for SQV (600 mg BID regimen) and RTV (100 mg BID).

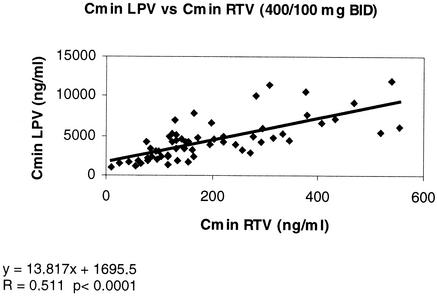

(iii) LPV and RTV.

Cmins of RTV and LPV (400 mg BID) also correlated with each other (r = 0.51 and P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3), again despite a wide dispersion of the data in this small subset of patients.

FIG. 3.

Correlation between Cmins for LPV (400 mg BID regimen) and RTV (100 mg BID).

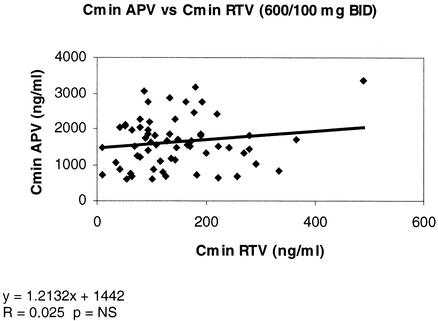

(iv) APV and RTV.

In contrast, Cmins of RTV and APV appeared to be independent of each other, regardless of the APV dose regimen. At a dose of 600 mg of APV BID, the correlation coefficient r was 0.025 (P > 0.1) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

No correlation between Cmins for APV (600 mg BID regimen) and RTV (100 mg BID). NS, not significant.

DISCUSSION

There has been a large increase in the use of low-dose RTV in combination with a variety of PIs over the last 2 years. SQV, IDV, and APV are now almost always prescribed in combination with RTV. RTV improves the pharmacokinetic profile of the different coadministered PIs by raising their concentrations in plasma, lengthening their half-lives of elimination, and reducing the influence of food on their gastrointestinal absorption. Therefore, an increase in drug exposure may improve, in some patients, virologic success. By reducing the number of pills and/or decreasing the frequency of doses and removing food restrictions, these RTV combinations may also improve patients' comfort and compliance (1, 3, 11).

However, despite the widespread use of such RTV/PI combinations, few data are available on the plasma PI concentrations achieved in clinical practice. Available data on the clinical pharmacology of PIs were obtained in small groups of patients and under experimental conditions that differ somewhat from the usual ambulatory follow-up of HIV-infected patients.

In France, therapeutic drug monitoring of antiretroviral treatments is increasingly used to determine the best dosage regimen adapted to each individual patient in order to reduce the risk of virologic failure (due to low plasma drug concentrations), to limit the toxicity linked to high plasma drug concentrations, and also to facilitate treatment from the patient's point of view. Therapeutic drug monitoring of these drugs could provide practical information for clinicians (3, 15).

In this retrospective study of a large cohort of ambulatory patients managed in two specialized hospital units, we assessed the interindividual and intraindividual variability of plasma PI concentrations obtained during routine assays in patients treated with RTV-boosted PI combinations. To avoid bias due to retrospective data analysis, patients have been carefully selected. They need to receive RTV (100 mg BID) in a first-line treatment of dual-PI regimen. If they had received successive PI/RTV dual combinations, only pharmacological data collected during the first PI/RTV dual regimen were used in this study. Patients treated with drugs known to have potent pharmacological interactions with PIs (rifampin, rifabutin, ketoconazole, itraconazole, and phenobarbital) were excluded from the analysis, as were patients receiving nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. For patients who underwent several consecutive drug determinations before and after a change in the dosage of the PI combined with RTV, only the initial values (collected during the first PI dosage) were used for the analysis of interindividual variability. For patients who had been on a stable antiretroviral combination for at least 2 weeks, only samples taken within the allocated interval (12 ± 2 h after the last dose) were used here.

The nurse in charge of taking blood samples for pharmacological assays systematically asked patients about compliance with the drug treatment during the two previous days and noted the exact time of the last drug dose taken. A patient who forgot one dose during the two previous days was considered noncompliant and excluded from the analysis.

Compliance of antiretroviral therapy is difficult to assess in clinical practice, and collecting information about drug intake regularity is always partially inaccurate. This inaccuracy could probably be limited by using the most recent recollection of the patient, and that is why we usually focused questions about treatment compliance on the last 2 days. All patients were informed about the pharmacological assays. One can therefore assume that the degree of inaccuracy in the results due to compliance problems was equally distributed among the groups.

Interindividual variability of plasma RTV concentrations.

Large interindividual variability of mean RTV Cmins was observed among the different groups of patients (coefficient of variation, 57.4 to 99.9%). Variability of mean RTV Cmins was found to be lower in patients receiving combinations containing APV or LPV (59.9 and 57.4%) than in those receiving combinations containing SQV or IDV (71.7, 76.1, and 95.4% for IDV and 70.8 and 77.9% for SQV) irrespective of the dose of the coadministered PI, as shown by coefficients of variation. Mean RTV Cmins were found to be significantly lower in patients receiving combinations containing APV or LPV than in those receiving combinations containing SQV or IDV. These results could be explained by an induction effect of LPV and APV on the metabolism of RTV.

This observation should be taken into account when another PI must be added to a combination of LPV/RTV or APV/RTV in salvage therapy. Indeed, if plasma RTV concentrations are reduced by APV or LPV, the expected booster effect of RTV on the third PI contained in the combination may be correspondingly reduced (9).

In some patients receiving the SQV/RTV or IDV/RTV combination, we observed high RTV Cmins, so this PI may participate directly to the overall antiretroviral activity. However, in patients receiving the APV/RTV or LPV/RTV combination, RTV Cmin always remained under its minimal effective trough level in plasma.

Interindividual variability of plasma drug concentrations of the PI combined with RTV.

Large interindividual Cmin variability of PIs was observed during treatment without RTV among our patients (61.7, 69.3, and 182.5% for APV, NFV, and IDV, respectively), as in previous studies (4, 5, 12, 16). Interestingly, despite the pharmacokinetic enhancement of these PIs by the addition of low-dose RTV, the interindividual variability of these concentrations remains high in our study (45.0, 74.6, and 78.8%, respectively). With the most common PI dose regimens (800, 600, and 400 mg of IDV BID; 800 and 600 mg of SQV BID; and 400 mg of LPV or APV BID), the interindividual Cmin variability of the PI combined with RTV was lower for LPV and APV (51.6 and 45%) than for IDV (76.5 to 92.0%) or SQV (83.7 to 106.3%) in terms of coefficients of variation observed at a given dose regimen.

The interindividual variability of PI concentrations probably depends on many parameters, including intestinal and hepatic metabolism, body weight (or the body mass index), age, gender, genetic factors, viral hepatitis or opportunistic infections, alcohol consumption, etc. Nonoptimal treatment compliance (drug not taken or inadequate time between medications or between drug intake and plasma sampling) participate in this overall variability. However, if the drug dose was taken later than scheduled, the inadequate time between the last drug dose and plasma sample would introduce less variability for PIs with longer half-lives. Therefore, with respect to their terminal half-life, the interpatient variability in Cmins of boosted LPV and APV could be lower than for the other PIs.

However, pharmacological interactions between RTV and the different PIs are different for the different combinations, as shown here.

Intraindividual variability.

Regarding intraindividual variability, all the assay values used here were obtained after at least 14 days of stable treatment, suggesting that our results were not influenced by the autoinduction of RTV metabolism observed during the first days of treatment with this PI. Treatment compliance may play a determining role (especially with respect to the dosing schedule).

The overall intraindividual RTV and PI Cmin variability was smaller than the corresponding interindividual variability.

The wide intraindividual variability must be taken into account in order to avoid erroneous dosage adjustment based on a single trough drug concentration measurement. For these reasons, we perform the first assay after 2 weeks of treatment, with at least one further assay after 2 months if the dosage regimen remains unchanged. If the dosage was adjusted, another drug determination was made after 2 weeks.

Correlations between the Cmins of RTV and PI for different RTV/PI combinations.

The study of the relationship between the Cmins of RTV and the PI in patients given RTV/PI combinations, expressed in terms of their correlation (linear regression), showed significant positive correlations in the case of IDV, SQV, and LPV (P < 0.0001). In contrast, no such correlation was found between the RTV and APV Cmins (P > 0.1).

The increase in the concentration of RTV in plasma therefore accentuates its booster effect on IDV, SQV, and LPV, but not APV. According to these results, the Cmins of IDV, SQV, and LPV can be raised by increasing the dose regimen of either RTV or PI. However, in the case of APV, only an increase in the APV dosage will increase its Cmin, in accordance with previous findings in healthy volunteers (B. M. Sadler, P. J. Pileiro, S. L. Preston, L. Yu, and D. L. Stein, Abstr. 7th Conf. Retrovir. Opportun. Infect., abstr. 77, 2000).

According to the observed correlations between PI and RTV Cmins, inter- and intraindividual variability of PI Cmins could be partially due to those of RTV Cmins, except for APV.

Many retrospective studies have reported concentration relationships between the exposure to PIs and antiretroviral efficacy and/or a related toxicity (2, 6-8, 14). The use of low-dose RTV in combination with various PIs improves the pharmacokinetic profile of the PI given in combination with RTV, thereby in theory reducing the risk of suboptimal or toxic plasma PI concentrations. However, the inter- and intraindividual variability of plasma drug concentrations of RTV and the coadministered PI remains high in patients thus treated. Consequently, therapeutic drug monitoring of PIs may represent an additional tool for the management of HIV-infected patients either to improve antiretroviral response or to decrease toxicity. Individual dosage adjustments must take into account the specificity of each pharmacological interaction, but the clinical relevance and benefit of therapeutic drug monitoring remain to be demonstrated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acosta, E. P. 2002. Pharmacokinetic enhancement of protease inhibitors. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 29(Suppl. 1):S11-S18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Acosta, E. P., K. Henry, L. Baken, L. M. Page, and C. V. Fletcher. 1999. Indinavir concentrations and antiviral effect. Pharmacotherapy 19:708-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Back, D. J., S. H. Khoo, S. E. Gibbons, and C. Merry. 2001. The role of therapeutic drug monitoring in treatment of HIV infection. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52(Suppl. 1):89S-96S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Baede-van Dijk, P. A., P. W. Hugen, C. P. Verweij-van Wissen, P. P. Koopmans, D. M. Burger, and Y. A. Hekster. 2001. Analysis of variation in plasma concentrations of nelfinavir and its active metabolite M8 in HIV-positive patients. AIDS 15:991-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardsley-Elliot, A., and G. L. Plosker. 2000. Nelfinavir: an update on its use in HIV infection. Drugs 59:581-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dieleman, J. P., I. C. Gyssens, M. E. Van der Ende, S. de Marie, and D. M. Burger. 1999. Urological complaints in relation to indinavir plasma concentrations in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 13:473-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gatti, G., A. Di Baggio, R. Casazza, C. De Pascalis, M. Bassetti, M. Cruciani, S. Vella, and D. Bassetti. 1999. The relationship between ritonavir plasma levels and side-effects: implications for therapeutic drug monitoring. AIDS 13:2083-2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gieshke, R., B. Fotteler, N. Buss, and J. L. Steiner. 1999. Relationship between exposure to saquinavir monotherapy and antiviral response in HIV-positive patients. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 37:75-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu, A., G. R. Granneman, G. Gao, L. Carothers, A. Japour, T. El-Shourbagy, S. Dennis, J. Berg, K. Erdman, J. M. Leonard, and E. Sun. 1998. Pharmacokinetic interaction between ritonavir and indinavir in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:2784-2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kempf, D. J., K. C. Marsh, G. Kumar, A. D. Rodrigues, J. F. Denissen, E. McDonald, M. J. Kukulka, A. Hsu, G. R. Granneman, P. A. Baroldi, E. Sun, D. Pizzuti, J. J. Plattner, D. W. Norbeck, and J. M. Leonard. 1997. Pharmacokinetic enhancement of inhibitors of the human immunodeficiency virus protease by coadministration with ritonavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:654-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moyle, G. J., and D. Back. 2001. Principles and practice of HIV-protease inhibitor pharmacoenhancement. HIV Med. 2:105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noble, S., and K. L. Goa. 2000. Amprenavir: a review of its clinical potential in patients with HIV infection. Drugs 60:1383-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pellegrin, I., D. Breilh, V. Birac, M. Deneyrolles, P. Mercie, A. Trylesinski, D. Neau, M. C. Saux, H. J. Fleury, and J. L. Pellegrin. 2001. Pharmacokinetics and resistance mutations affect virologic response to ritonavir/saquinavir-containing regimens. Ther. Drug Monit. 23:332-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pellegrin, I., D. Breilh, F. Montestruc, A. Caumont, I. Garrigue, P. Morlat, C. LeCamus, M. C. Saux, H. J. Fleury, and J. L. Pellegrin. 2002. Virologic response to nelfinavir-based regimens: pharmacokinetics and drug resistance mutations (VIRAPHAR study). AIDS 16:1331-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poirier, J. M., P. Robidou, and P. Jaillon. 2002. Simultaneous determination of the six HIV-protease inhibitors (amprenavir, indinavir, LPV, nelfinavir, ritonavir, and saquinavir) plus M8 nelfinavir metabolite and the nonnucleoside reverse transcription inhibitor efavirenz in human plasma by solid-phase extraction and column liquid chromatography. Ther. Drug Monit. 24:302-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Heeswijk, R. P. G., A. I. Veldkamp, R. M. W. Hoetelmans, J. W. Mulder, G. Schreij, A. Hsu, J. M. A. Lange, J. H. Beijnen, and P. L. Meenhorst. 1999. The steady state plasma pharmacokinetics of indinavir alone and in combination with a low dose of ritonavir in twice daily dosing regimens in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS 13:95-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]