Abstract

We found an increased abundance of pbpB-specific transcripts in vancomycin intermediate-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) isolates compared with that found in paired, genetically identical, susceptible isolates. This difference in expression cannot be explained by differences in the pbpB promoter sequence. Since the factors controlling pbpB gene expression have remained largely unexplored, various conditions that might affect pbpB transcript abundance were examined. In both vancomycin-susceptible and VISA strains, pbpB expression varied with the growth phase, with the highest abundance of pbpB-specific transcripts detected during mid-log phase. Interestingly, both vancomycin and oxacillin were able to induce pbpB transcription above a constitutive level. When vancomycin was absent, one of the three pbpB-specific transcripts that were usually faintly detected in non-VISA strains was more readily detected in VISA strains during mid-log but not stationary phase. This transcript was enhanced in non-VISA strains by vancomycin induction. Gel shift assays indicated that an increased amount of the putative transcription factor that binds to both P1 and P1′ promoter regions is present in the cytosol of vancomycin-induced cells. Neither the SigB sigma factor nor the quorum-sensing agr locus was required for growth phase-variable pbpB expression or transcriptional induction of pbpB by vancomycin or oxacillin. Also, MecI, MecR1, BlaI, and BlaR1, regulatory proteins that mediate β-lactam-inducible expression of mecA and β-lactamase, were not required for antibiotic induction of pbpB transcription. These data support the idea that pbpB expression is modulated by a trans-acting factor in response to the presence of the cell wall-active antibiotics vancomycin and oxacillin.

Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus has been a persistent clinical problem and has risen in prevalence in many geographic locations throughout the world (16). Glycopeptides such as vancomycin and teicoplanin are often the agents of choice for treating infections caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). However, vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) clinical isolates that were obtained during prolonged, unsuccessful vancomycin therapy have been recognized in the past 5 years (reviewed in reference 18). Also, two vancomycin-resistant clinical S. aureus isolates for which vancomycin MICs are high (> 128 mg/liter) were recently identified that have proven positive for the enterococcal vanA gene (8). Given the history of ever-increasing resistance among MRSA strains, such strains are likely to become more prevalent in the future, a situation that would severely restrict treatment options for infections by this virulent pathogen.

Using complementary mechanisms, both β-lactam and glycopeptide antimicrobials inhibit cell wall biosynthesis. β-Lactams bind to and inhibit penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which are the enzymes involved in peptidoglycan synthesis, cell growth, and morphogenesis (47). Vancomycin interferes with the action of PBPs by binding to the d-Ala-d-Ala terminus of the peptidoglycan precursor, the substrate on which PBPs act (reviewed in reference 18). Therefore, an understanding of the factors affecting expression of PBPs might lead to the identification of novel targets for antimicrobial therapy against MRSA (and particularly VISA) isolates, for which few therapeutic alternatives exist.

Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus isolates produce five PBPs, PBP1, PBP2, PBP2B, PBP3, and PBP4, for which the genes have been cloned and sequenced (21, 28, 34, 38, 43, 51). MRSA isolates have acquired an additional PBP, termed PBP2′ or PBP2a, that has low affinity for β-lactam antibiotics and substitutes for the other PBPs in cell wall synthesis when they are inhibited by β-lactams (reviewed in reference 10). PBP2a is encoded by the mecA gene, which is carried on a large mobile genetic element (referred to as SCCmec [24, 27, 30]) that is integrated into the chromosome of MRSA strains. It has recently been revealed that the ability of PBP2a to effect cell wall synthesis in the presence of methicillin requires cooperation from the transglycosylase domain of the native PBP2 (37, 40). Also ascribed to PBP2 is a role in borderline resistance to methicillin in strains that do not contain mecA (2, 12, 50).

It has previously been demonstrated by the results of penicillin-binding assays and Western blotting that VISA strains (both clinical and laboratory-derived isolates) and a teicoplanin intermediate-resistant clinical isolate had increased PBP2 production compared with their respective related susceptible isolates (20, 33, 44). Such differences suggested that expression of the pbpB gene was up-regulated in VISA isolates and was therefore subject to genetic control. Such an increase might mean either that PBP2 is involved in vancomycin resistance or that the gene encoding PBP2 is coregulated with vancomycin resistance genes. One model to explain vancomycin resistance involves thickening of the cell wall, which might require increased peptidoglycan synthesis (22). When pbpB was overexpressed from a multicopy plasmid, susceptibility to vancomycin was decreased compared with that of the parent strain, a finding that suggested that an increased level of PBP2 plays an accessory role in the vancomycin resistance mechanism (20).

Transcription of the mecA gene is induced in some isolates by β-lactams, and such induction is regulated by MecI and MecR1, a repressor and a signal-transducing protein, respectively (10). The mecI and mecR1 genes, when present, are carried beside mecA on the SCCmec element (24, 27, 30). Cross-regulation by BlaI and BlaR1 of mecA transcription also occurs, encoded by blaI and blaR1 genes carried on the β-lactamase plasmid along with blaZ (10). Until now, the background PBPs in S. aureus have been assumed to be constitutively expressed.

Although constitutive pbpB transcription has been studied recently (39), the factors that control or induce pbpB gene expression have not yet been explored. We characterized the pbpB transcriptional response to growth phase and the presence of the cell wall-active antibiotics vancomycin and oxacillin. These data support the idea that pbpB expression at the transcription level is modulated in response to growth phase and by cell wall-active antibiotics. These data further suggest that induction of the pbpB gene by vancomycin and oxacillin is controlled by a putative regulatory system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates and growth conditions.

S. aureus cultures were routinely grown at 37°C. For long-term storage, cultures were maintained at −70°C in skim milk (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) as previously described (15). The VISA derivative 523k was described previously (15), having been produced as the last of a series of isolates obtained after incubation of the glycopeptide-susceptible clinical isolate 523 in successively increasing concentrations of vancomycin. The clinical VISA isolate, IL-F (5, 7, 9), was the last isolated from a series of six clonally identical MRSA blood isolates obtained from a dialysis patient who was receiving vancomycin therapy. The broth MICs of vancomycin and teicoplanin were 12 to 16 μg/ml. Strain IL-A, the initial isolate from this patient, was susceptible to vancomycin by broth MIC analysis (MIC ≤ 4 mg/liter). However, susceptibility testing by population analysis revealed that strain IL-A was vancomycin heteroresistant, because it contained a subpopulation capable of growing on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar medium containing 5 mg of vancomycin/liter (5). Since IL-F was shown to be derived from strain IL-A (confirmed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of SmaI digested genomic DNA) (5), this pair of isolates provides an ideal model system for studying the development of clinically relevant vancomycin resistance among MRSA strains. Strain RN6911, generously provided by Richard Novick, contains a tetracycline resistance gene replacing the agr locus, as described previously (35). Strain 1715 is a methicillin-susceptible, vancomycin-susceptible, β-lactamase-negative clinical isolate that therefore likely lacks MecI, MecR1, BlaI, and BlaR1 genes.

Western blotting (immunoblotting).

Membrane fractions were prepared by differential centrifugation of cell lysates as described previously (33). Immunoblotting to detect the PBP2 protein was performed with the use of antiserum kindly provided by Kazuhisa Murakami (Shionogi Research Laboratories, Osaka, Japan) as previously described (33).

Northern (RNA) blotting.

To study the effect of vancomycin on pbpB gene induction, the bacterial cultures were grown for 16 h and then diluted 1:100 in fresh BHI broth (Difco). After 1 h of growth at 37°C, vancomycin was added to achieve a final concentration of 0, 2.5, 4, or 8 mg/liter. The bacterial cultures were collected for extraction of RNA after 1 and 3 h of growth. Similar conditions were used to evaluate the effect of oxacillin on pbpB expression. To isolate RNA, the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) was used as directed by the manufacturer except that lysis of cells was facilitated by using recombinant lysostaphin (Sigma) to digest cell walls, as described previously (6). RNA purity was determined from the A260/A280 ratio. RNA (5 μg) was electrophoresed through a 1.2% agarose-0.246 M formaldehyde gel in MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) running buffer (20 mM MOPS, 5 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0) containing 0.246 M formaldehyde. To assure that equivalent amounts of RNA were compared, each RNA sample was run in parallel and the intensity of the rRNA bands was visualized by UV illumination of ethidium bromide-stained gels or by methylene blue staining of the transfer membrane, as previously described (6). Using 10× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) as the transfer buffer, RNA was transferred onto a GeneScreen Plus membrane (Perkin-Elmer Life Science) and fixed by UV cross-linking. The probe used for detecting the pbpB transcripts was either a 826-bp PCR amplimer produced from chromosomal DNA with primers pbpBF (5′-TGTGAAGAGAACGATTATTAAG-3′) and pbpBR (5′-ATGAATTATACTCAGAATCTTGAT-3′) designed from the pbpB gene sequence (34) or a 791-bp pbpB DNA PCR fragment obtained using primers pbpB-F2 (5′-ATCATACTAGCCATAAAGCG-3′) and pbpB-R2 (5′-CCAATAATTTTACATAGCTAAAG-3′). The prfA gene probe was a 233-bp PCR amplimer obtained using the primers prfA-F (5′-AGACGGAGGGAAAAAGAC-3′) and prfA-R (5′-CCGTTGTAATCAGTTGTTGAAG-3′). The probes were labeled using either the RadPrime DNA labeling kit (Gibco BRL) or the Prime-a-Gene labeling system (Promega) by random primer synthesis with the use of [α-32P]dATP (Amersham). Hybridization was performed under high-stringency conditions with either a standard formamide hybridization buffer and an incubation temperature of 42°C or a sodium dodecyl sulfate hybridization buffer (7% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% bovine serum albumin, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25 M NaH2PO4 [pH 7.2]) and an incubation temperature of 70°C. The rinsed membranes were exposed to film (Hyperfilm-MP; Amersham) with an intensifying screen at −70°C.

DNA sequencing.

Using agarose gel-purified PCR products produced with primers designed from published sequences (34, 39), the prfA and pbpB genes of strains IL-A and IL-F were sequenced with a primer-walking strategy. Sequencing reactions were performed with fluorescent dideoxy chain termination chemistry and an ABI Prism sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) at The University of Chicago core sequencing facility. DNA sequence comparisons were performed using ClustalW alignment software (49).

Gel retardation assay.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared essentially as described previously by Mahmood and Khan (31). Cells from S. aureus strain IL-A (80 ml) were exposed to vancomycin at the beginning of log phase and were harvested 45 min after treatment with vancomycin. The cell pellets were washed once with TEG (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM EGTA) and centrifuged again. The pellets were resuspended in 2 ml of TEG, quickly frozen at −70°C, and thawed at room temperature. After two cycles of freeze-thaw, the cell suspension was adjusted to 0.15 M KCl. Lysostaphin (Sigma) was then added to achieve a final concentration of 0.3 mg/ml, and lysis was carried out at 4°C for 1 h. The freeze-thaw process was repeated twice, and the lysates were centrifuged at 30,000 rpm for 30 min in a Beckman Ti70 rotor. The supernatant was collected, and glycerol was added to a final concentration of 20% (vol/vol). The extracts were dialyzed at 4°C overnight against 1 liter of 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]-1 mM EDTA-1 mM dithiothreitol-50 mM NaCl-20% glycerol and then stored at −70°C.

(i) DNA probes.

Five overlapping DNA probes that spanned the prfA-pbpB promoter region (from 203 bp upstream through 92 bp downstream from the P1 transcription start point [tsp]) were produced by PCR amplification of purified chromosomal DNA (Qiagen) from strain IL-A as follows. The 141-bp fragment Up (203 through 63 bp upstream from the P1 tsp) was amplified using primers UPF (5′-CACATACTTGTACTTGCCTC-3′) and UPR (5′-GTTGGAATTTTACACACAAT-3′). The 90-bp fragment P1 (76 bp upstream through 14 bp upstream of the P1 tsp) was amplified using primers P1F (5′-TGTAAAATTCCAACATTAAC-3′) and P1R (5′-GACACAATACACCAAAGC-3′. The 168-bp fragment P1+P1′ (76 bp upstream and 92 bp downstream of the P1 tsp) was amplified using primers P1+P1′F(5′-TGTAAAATTCCAACATTAAC-3′) and P1+P1′R (5′-CAAGTTTGGTAGTAAACGTTG-3′). The 99-bp fragment P1′ (7 bp upstream through 92 bp downstream of the P1 tsp) was amplified using primers P1′F (5′-AAGCTTGGTGTATTGTG-3′) and P1′R (5′-CAAGTTTGGTAGTAAACGTTG-3′). The 68-bp fragment P1′S (+24 through +92 bp downstream from the P1 tsp) was amplified using primers P1′SF (5′-TACTAATTTAAGTTTGGTGTTTC-3′) and P1′SR (5′-CAAGTTTGGTAGTAAACGTTG-3′). Using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega) as recommended by the manufacturer, the PCR fragments were gel purified and end labeled with [γ32P]ATP (Amersham).

(ii) DNA-protein binding reactions.

The reaction mixtures consisted of a solution containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 50 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC), ∼5 ng of [γ-32P]ATP end-labeled DNA fragments, and 5 μg of whole-cell protein extract in a final volume of 15 μl. The reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and the resulting DNA-protein complexes were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel buffered with 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. Gels were dried on 3MM Whatman paper and exposed with X-ray film at room temperature.

RESULTS

Differential expression of the pbpB gene between genetically related vancomycin-susceptible and -resistant isolates.

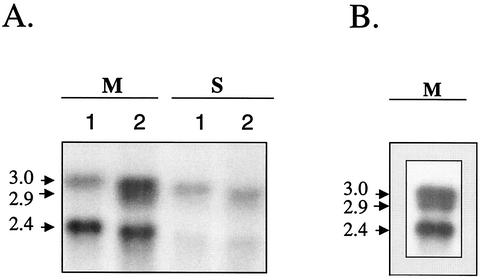

To determine whether the increased PBP2 production previously observed in strain 523k, the laboratory-derived VISA strain, was due to increased transcription of the pbpB gene, the abundance levels of pbpB-specific transcripts in strain 523k and in strain 523, the isogenic-susceptible parent strain, were compared by Northern blotting (see probe b in the map in Fig. 1). As shown by the Northern blot in Fig. 2, the abundance of the pbpB transcripts was at least twofold greater in isolate 523k. The pbpB probe detected 3-kb and 2.4-kb transcripts in strain 523 (the latter band was determined by comigration in the gel beside the 2.4-kb band in the RNA standard); these two transcripts likely correspond to the 2.9- and 2.1-kb pbpB major transcripts, respectively, referred to previously by Pinho et al. (39). Interestingly, an additional, 2-kb transcript was detected in the 523k VISA isolate. This transcript migrated slightly beneath the 3.0-kb band such that the signals from the 3.0- and 2.9-kb bands often merged into one. Thus, the combined signal of these two bands was referred to as the 3.0-kb doublet. When the exposure time of the autoradiograph was increased or higher concentrations of RNA were applied to the agarose gel, the 2.9-kb band also became more apparent in strain 523 (Fig. 2B). Thus, the 2.9-kb band of the 3.0-kb doublet was expressed to a lesser extent in strain 523 than it was in strain 523k.

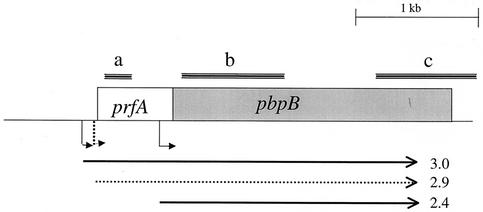

FIG. 1.

Map depicting the prfA-pbpB operon and the three transcripts (arrows below the map) detected by various probes (a, b, and c) used in Northern blotting. The dotted 2.9-kb arrow represents the variable nature of that transcript's expression, which depends on the vancomycin susceptibility of the strain, the presence or absence of vancomycin, and the growth phase in which cultures were harvested (see text). tsps corresponding to each transcript (39) are depicted as bent arrows.

FIG. 2.

Differential expression levels of pbpB between strains 523 and 523k. (A) Northern blot probed with the pbpB probe in vancomycin-susceptible isolate 523 (lane 1) and VISA strain 523k (lane 2). Isolates were harvested in the mid-exponential (M) and stationary (S) growth phases. The blot was hybridized under stringent conditions, as described in Materials and Methods, with pbpB gene probe b (Fig. 1). (B) Northern blot of RNA from strain 523 that was probed with the pbpB probe. The autoradiograph was overexposed to amplify the presence of the 2.9-kb band in strain 523.

Growth-phase variation of pbpB transcript abundance.

The abundance of the transcripts detected by the pbpB probe was highest for both strains 523 and 523k during the mid-logarithmic growth phase and decreased substantially in the stationary phase (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the smaller band of the 3.0-kb doublet was no longer detected by the pbpB probe in the post-exponential phase of growth in either strain 523 or 523k. With the drastic decrease in pbpB transcript abundance in the post-exponential phase, there was no longer a marked difference in transcript abundance between strains 523 and 523k.

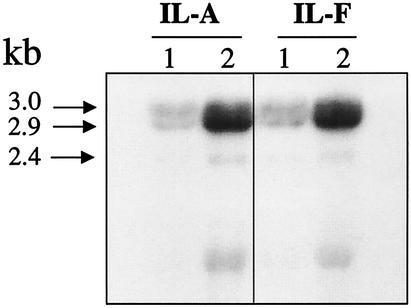

Increased expression of pbpB in clinical VISA isolate IL-F.

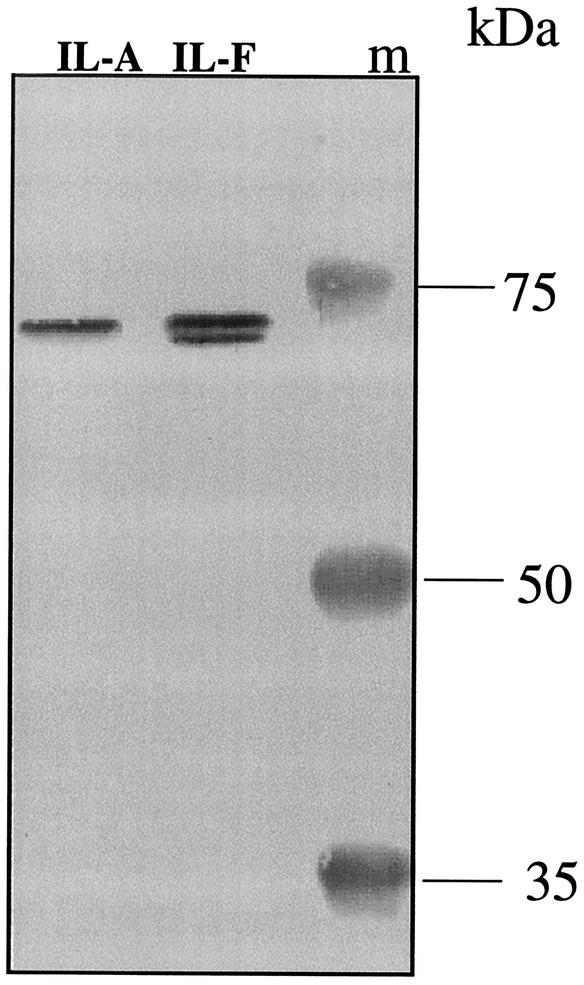

To determine whether the increased pbpB expression observed in strain 523k also occurred in clinical VISA strains selected in vivo during antimicrobial therapy, expression of pbpB was compared between two genetically related strains, strain IL-A (vancomycin-heteroresistant MRSA) and strain IL-F (VISA), that were obtained from the same patient but that differed in vancomycin susceptibility. The abundance of the PBP2 protein was about twofold greater in the clinical VISA strain IL-F than that detected in the related heteroresistant strain, IL-A, as determined by Western blotting (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the Western blot clearly shows that strain IL-F produced the additional proteolytic cleavage product of PBP2 described previously (11, 12, 33) whereas the more susceptible isolate did not. As shown in the Northern blot (Fig. 4, lanes 1) and the densitometry measurements (Table 1), the pbpB transcript abundance was twofold greater in the VISA strain IL-F than in strain IL-A. As occurred for strains 523 and 523k, the abundance of the pbpB transcript also decreased during the stationary phase in strains IL-A and IL-F (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Western blot of membrane fractions from strains IL-A (left lane) and IL-F (center lane) probed with an antibody against PBP2. Strains IL-A and IL-F were harvested during mid-log phase, and membrane fractions were prepared and subjected to Western blotting against a PBP2 polyclonal antibody as described in Materials and Methods. Perfect Protein markers (Novagen) were used for the molecular mass ladder (lane m).

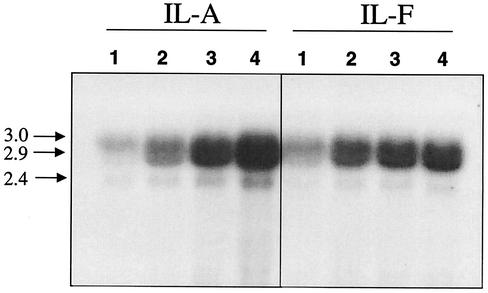

FIG. 4.

Dose response of vancomycin induction of pbpB transcription in strains IL-A and IL-F. Bacteria were exposed to either no vancomycin (lanes 1) or 2.5 (lanes 2), 4.0 (lanes 3), or 8 (lanes 4) mg of vancomycin/liter, and RNA was harvested at 1 h postexposure. The blot was probed with probe c as shown in the map in Fig. 2. The net intensities of the 3.0-kb doublet from each concentration of drug are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Net intensities of pbpB transcripts induced by vancomycina

| Strain | Net intensity of transcript at a vancomycin concn (mg/liter) of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.5 | 4 | 8 | |

| IL-A | 67,000 | 187,000 | 295,000 | 370,000 |

| IL-F | 139,000 | 247,000 | 261,000 | 285,000 |

Expressed as net intensity of the 3.0-kb doublet detected in strains IL-A and IL-F in the Northern blot shown in Fig. 3. Measurements were determined using 1D Image Analysis software (Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.).

Induction of prfA-pbpB transcripts by vancomycin.

Since PBP2 transcript abundance was increased in VISA strains compared with related susceptible isolates, we hypothesized that vancomycin can induce expression of pbpB. A dose-response study of the inducing effect of vancomycin on prfA-pbpB transcript abundance was performed by incubating strains IL-A and IL-F in BHI broth containing 0, 2.5, 4, or 8 mg of vancomycin/liter and harvesting RNA from the cells during the mid-logarithmic and late logarithmic growth phases. As seen in the Northern blots probed with the pbpB probe (Fig. 4, lanes 2, 3, and 4), when vancomycin was present in the medium, the abundance of the 3.0-, 2.9-, and 2.4-kb pbpB transcripts increased in both strains compared with that produced when each isolate was grown in the absence of vancomycin (lanes 1, baseline). However, quantification of the signal intensities from the 3.0-kb doublet revealed that, surprisingly, the kinetics of induction differed for the two strains (Table 1). In strain IL-A, a 3-fold induction over baseline was observed when 2.5 mg of vancomycin/liter was added to the medium and a further increase occurred with each increase in the drug concentration, with a 5.5-fold induction resulting when 8 mg of vancomycin/liter was used. In strain IL-F, a 1.7-fold induction occurred with 2.5 mg of vancomycin/liter but a plateau was reached with higher concentrations of up to 8 mg of vancomycin/liter. Moreover, at 8 mg of vancomycin/liter, the pbpB transcript abundance in strain IL-A became greater than that of strain IL-F (Table 1). Thus, the vancomycin-inducing potential of pbpB was actually lower in the VISA strain. No further increases occurred in either strain when 16 mg of vancomycin/liter was used in the growth medium (data not shown). The 2.4-kb pbpB transcript appeared in much lower abundance than the 3.0-kb doublet, but induction of this transcript followed a dose response similar to that of the 3.0-kb prfA-pbpB doublet.

Characterization of transcripts.

As illustrated in the map in Fig. 1, immediately upstream of the pbpB open reading frame (ORF) and encoded within the same operon is a gene called prfA (PBP-related factor A), which has homologues in other gram-positive species (36, 39). Using a primer internal to prfA and another internal to pbpB, a fragment was amplified previously from cDNA by reverse transcriptase PCR that indicated that the two ORFs can be transcribed together (39). However, direct evidence by Northern blotting with prfA or pbpB probes was lacking, and with the discovery that there are two transcripts in the 3.0-kb doublet, we wanted to confirm that both transcripts present in the 3.0-kb doublet contained both prfA and pbpB genes. Thus, Northern blotting was performed using a prfA gene probe that did not overlap with the 2.4-kb transcript (probe a; Fig. 1). The prfA probe hybridized to both the 2.9- and 3.0-kb bands but not the 2.4-kb transcript (data not shown). Thus, both bands that comprise the upper 3.0-kb doublet contained both the prfA and pbpB genes and the 2.4-kb transcript only contains pbpB.

DNA sequence of the pbpB gene of strains IL-A and IL-F.

The prfA and pbpB gene sequences of strains IL-A and IL-F were determined to assess whether changes in DNA sequence in the promoter region accounted for the observed increases in prfA-pbpB transcript abundance. The sequences of the entire pbpB operons were identical in strains IL-A (accession number AF508980) and IL-F (accession number AF508981), including those of the three promoter regions (P1, P1′, and P2) (39). The DNA sequence of the pbpB operon from the IL strains was also compared with those from strains Mu50 (AP003133), N315 (AP003362), and COL (Y17795), which were available in the GenBank. Whereas nine nucleotide mismatches were found between the IL isolates and strain COL, only two mismatches were present between the IL isolates and strains Mu50 and N315. Although all of the interstrain nucleotide differences were contained in the pbpB ORF, only one resulted in an amino acid difference between the IL strains and the others. Compared with strains Mu50, N315, and COL, both IL-A and IL-F contained a nucleotide mismatch (a T instead of C at nucleotide 3473 of the COL sequence [Y17795]) that resulted in a single amino acid difference (a leucine in strains IL-A and IL-F instead of serine in strains Mu50, N315, and COL) in residue 707 of the translated protein (relative to the sequence in the database at accession number CAA76853). This polymorphism lies at the carboxyl terminus of the translated protein and outside the known penicillin-binding motifs and the transpeptidase and transglycosylase domains. This unique polymorphism in strains IL-A and IL-F and the phylogeny trees produced from the sequence alignments (data not shown) reinforce the previous conclusion that strain IL-F is derived from strain IL-A. Also, overall, the pbpB sequences from strains N315 and Mu50 were more closely related to each other than to those from either of the IL isolates.

Induction of prfA and pbpB transcripts by oxacillin.

Since PBP2 is a cofactor required for the synthesis of peptidoglycan in the presence of oxacillin, and since oxacillin is known to induce transcription of the methicillin resistance gene, mecA, we investigated whether oxacillin can also induce pbpB expression. When 4 mg of oxacillin/liter was added to cultures of strains IL-A and IL-F and cells were allowed to grow for an additional hour, the abundance of the 3.0-kb pbpB doublet increased 4- and 3.2-fold for strains IL-A and IL-F, respectively (Fig. 5). As expected, the mecA gene transcript was also induced by oxacillin under these conditions (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Oxacillin induction of the pbpB gene. Northern blot of RNA from strains IL-A and IL-F probed with a pbpB probe. Strains IL-A and IL-F were exposed to 0 (lane 1) or 4 (lane 2) mg of oxacillin/liter and harvested 1 h later.

Effect of inactivation of agr on pbpB growth phase-regulated gene expression and induction by vancomycin.

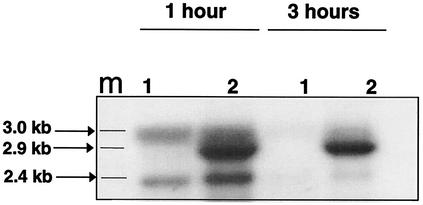

S. aureus controls the expression of many extracellular gene products by using a growth-regulated, quorum-sensing system encoded by the agr locus (26, 35). To investigate whether agr also plays a role in the growth phase-regulated expression of the pbpB gene, we tested whether inactivation of agr alters pbpB transcript abundance in mid-log and stationary growth phases. To this end, Northern blotting of RNA from strain RN6911, which has the entire agr locus replaced by a tetracycline resistance gene, was performed using a pbpB gene probe. As was the case for expression of the gene in strains 523, 523k, IL-A, and IL-F, pbpB gene expression in strain RN6911 was high during the mid-log phase and dramatically lower in stationary phase (Fig. 6). Also, pbpB transcript abundance from strain RN6911 increased when grown under vancomycin-inducing conditions (Fig. 6). Such induction was observed 1 and 3 h after vancomycin was added to the culture medium. Similarly, the inactivation of agr did not alter the ability of oxacillin to induce pbpB transcription (data not shown). These data demonstrate that although agr regulates expression of many extracellular proteins in a growth phase-dependent manner, it is not responsible for growth-phase control or induction of pbpB gene expression in the presence or absence of vancomycin or oxacillin.

FIG. 6.

pbpB gene expression in an agr knockout strain. Northern blot of RNA from strain RN6911 grown in the absence (lanes 1) or presence (lanes 2) of vancomycin (4 mg/liter) and harvested 1 h or 3 h after vancomycin was added. The Northern blot was probed with pbpB probe c (Fig. 1). Lane m indicates positions of the 3.0- and 2.4-kb markers from the RNA standard (Gibco BRL).

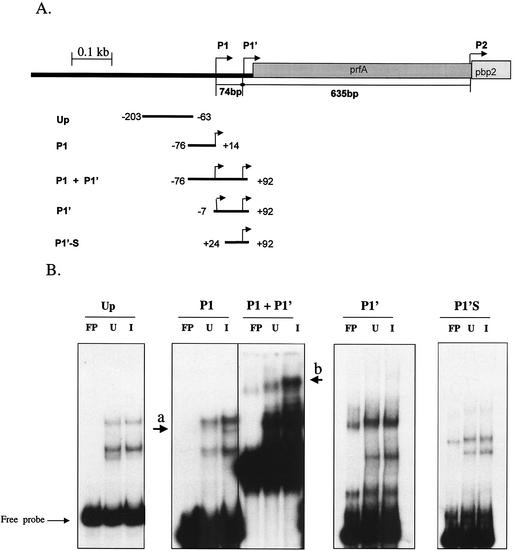

Gel retardation assay.

To determine whether vancomycin induces the expression of a transcription factor that directly binds to the pbpB promoter and to determine which portion of the pbpB promoter is important for binding, gel retardation assays were performed. This assay relies on the fact that proteins that bind to a DNA fragment retard the mobility of the fragment in a gel during electrophoresis. Five overlapping fragments (illustrated in Fig. 7) that spanned the entire prfA-pbpB promoter region were radiolabeled and incubated with extracts from vancomycin-induced and uninduced cells in the presence of excess cold competitor DNA. When the fragment (P1) that contained only the P1 promoter (−76 through +14 bp relative to the P1 tsp) was used, extracts from both induced and uninduced cells produced two major retarded species that were absent from the control lane containing the radiolabeled probe not exposed to protein extracts (free probe). The extracts from the vancomycin-induced cultures produced a third minor band of retarded mobility in the gel (Fig. 7, arrow a). Moreover, the signal intensity was greater in the fragments retarded by proteins from vancomycin-induced cells than in those by retarded by proteins from uninduced cells. Thus, the induced cultures contained either a greater abundance of protein capable of binding to the P1 promoter or a protein with a greater affinity for the P1 promoter.

FIG. 7.

Gel retardation assay. (A) Overlapping fragments from the prfA-pbpB promoter used in the gel shift assay were generated by PCR and end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP as described in Materials and Methods. All reactions were performed in the presence of excess poly(dI-dC) competitor DNA. (B) Autoradiograms of gel shift assays. Extracts from uninduced (U) and vancomycin-induced (I) cells from strain IL-A were incubated with various promoter fragments and resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods. FP, free probe.

A second fragment (P1+P1′) was also tested. This fragment contained an additional 78 bp downstream of the P1 promoter (−76 through +92 bp relative to the P1 tsp) and included both the P1 and P1′ promoters. Compared with the P1 fragment, a greater amount of the P1+P1′ probe was bound by protein from either extract, as judged by the signal intensities of the retarded species in the respective autoradiographs. Also, protein extracts from vancomycin-induced cells produced a larger number of retarded species of the P1+P1′ fragment with increased intensity than did the extracts from uninduced cultures or free probe. For example, a single fragment of retarded mobility present in the lane containing free probe (Fig. 7, arrow b) was shifted slightly higher in the gel and became more intense upon exposure to either protein extract, but the intensity of this fragment increased in the vancomycin-induced extracts. Both the fragments with deletions of 69 bp (fragment P1′) and those with deletions of 100 bp (fragment P1′S) from the 5′ end of the P1+P1′ fragment abolished the differences observed between the uninduced and induced extracts, although retarded fragments were still produced by either extract. This finding suggests that the region between −76 and −7 bp upstream from the P1 tsp contains binding sites for a vancomycin-inducible transcription factor. These data also support the notion that vancomycin induces an increased amount of the putative transcription factor in the cytosol of vancomycin-induced cells. The increased binding characteristics of the P1+P1′ fragment compared with those of the P1 fragment suggests that cooperative binding occurred in the region that spans the P1 and P1′ promoters (−76 through +92 bp relative to the P1 tsp).

MecI, MecR1, BlaI, and BlaR1 are not involved in induction of the pbpB gene by vancomycin and oxacillin.

MecI-MecR1 and BlaI-BlaR1 regulatory complexes control β-lactam-dependent induction of mecA and blaZ genes, respectively. To examine whether these regulatory complexes also played a role in the induction of pbpB transcription by vancomycin and oxacillin, a methicillin-susceptible, β-lactamase-negative clinical strain (strain 1715), which therefore likely lacks these regulatory genes, was tested for the ability of these agents to induce pbpB transcription. This strain was fully capable of having its pbpB gene induced by these agents (data not shown). Thus, these regulatory proteins are not required for induction of pbpB transcription by these antimicrobials.

DISCUSSION

This report demonstrates that the transcription of pbpB and prfA transcripts in S. aureus is modulated in response to the growth phase and is induced by the cell wall-active antibiotics vancomycin and oxacillin. Additionally, this is the first demonstration that PBP2 production increased in a clinical VISA isolate (IL-F) compared with that in a genetically identical, more susceptible isolate (IL-A) obtained from the same patient during vancomycin therapy. These data extend the results of previous studies that demonstrated greater PBP2 production in VISA clinical isolates than in epidemiologically unrelated susceptible strains or in laboratory-derived VISA isolates (20, 33) and teicoplanin intermediate-resistant clinical isolates (32, 44). This report extends these previous observations by demonstrating that the increased production of PBP2 in the strains we tested was due to increased transcription of the pbpB gene.

An increase in pbpB transcript abundance in response to antibiotic-induced stress has not been previously reported. This is likely due to the fact that pbpB transcriptional activity has only recently been explored and that the optimal conditions for detecting such induction had not been known until now. Furthermore, although horizontally acquired genes that confer vancomycin or β-lactam resistance have been shown to be induced by their cognate antibiotics, antibiotic induction of housekeeping genes involved in cell wall biosynthesis has not been previously reported. Such induction makes sense for bacterial survival; an increased abundance of prfA-pbpB transcripts provides S. aureus with a rapid means to respond to the damaging effects of cell wall antibiotics by accelerating cell wall synthesis.

Depending on the growth or Northern blotting conditions, we found up to three pbpB-hybridizing transcripts (3.0, 2.9, and 2.4 kb) that were large enough to accommodate the pbpB ORF. The 2.9-kb transcript was not detected previously in Northern blots and was only recognized as a faint tsp, as detected by a primer extension analysis (39). This was likely due to the fact that the 2.9-kb transcript was usually less easily detectable in vancomycin-susceptible strains than in VISA strains. In contrast, in the VISA strains, this 2.9-kb band was consistently detected without the need for autoradiographic enhancement during the mid-log phase, although it was less readily detected during stationary phase.

In Streptococcus pyogenes and Bacillus subtilis, expression or production of PBPs has been shown to decrease in the post-exponential phase (42, 48). We provide evidence (by Northern blotting) that all three pbpB transcripts decrease during stationary phase in S. aureus, a result that extends the findings that the detection of tsps from two of the promoters (P1 and P2) decreased at the end of stationary phase (39). Thus, growth-regulated expression of PBP genes might be a general strategy used by bacteria. However, the genetic basis for this phenomenon has remained uncharacterized. Discovering the basis for this could lead to the identification of a novel target for antimicrobial therapy.

Growth phase-variable expression of many secreted and cell wall-associated virulence factors in S. aureus is controlled by the agr quorum-sensing system and the SarA global regulator (13, 35). Piriz Duran et al. reported that neither agr nor sar gene inactivation influenced PBP2 activity (41); however, that study focused on PBP activity during mid-log phase and did not investigate whether the effect of such inactivation influenced the decrease of PBP activity in stationary phase. Thus, our data now rule out a role for the agr locus in modulating growth phase-variable expression of the prfA-pbpB operon and for induction by antibiotics as well. In addition, with the finding that pbpB gene induction can be influenced by vancomycin in strain RN6911, a derivative of a natural rsbU mutant shown to lack SigB (an alternate sigma factor) activity (19), these data also indicate that an active form of SigB is not required for vancomycin-mediated induction of pbpB. It remains to be determined whether SarA is involved in antibiotic-mediated induction of pbpB expression. However, overexpression of the sarA gene on a multicopy plasmid in strain 523k did not alter expression of any of the pbpB transcripts in the absence of vancomycin or β-lactams (our unpublished data).

The role of pbpB overexpression in vancomycin resistance is not yet clear. However, several observations regarding VISA isolates support the idea that increased PBP production plays an accessory role in the resistance phenotype. A strategy for overcoming the inhibitory effect of vancomycin on cell wall synthesis might include maximizing the cell wall metabolic machinery. Accordingly, increased production of PBP2, increased cell wall thickness, accelerated cell wall metabolism in VISA isolates (as evidenced by increased incorporation of 14C-N-acetylglucosamine), release of this compound into liquid medium, and an increase in the murein monomer precursor pool might all aid in this regard (20). However, it is clear that the role of PBP2 in resistance to vancomycin also depends on other factors, since overproduction from a multicopy plasmid does not raise the vancomycin MIC to an intermediate level (≥8 mg/liter) (20). Of particular interest is the paradoxical finding that the vancomycin induction potential of pbpB expression became lower in VISA strain IL-F as the vancomycin concentration increased. Thus, although constitutive levels of pbpB transcription were slightly higher in strain IL-F, the absolute transcript abundance induced by vancomycin was lower in strain IL-F than in strain IL-A at concentrations higher than 4 mg of vancomycin/liter. The significance of this finding is that less PBP2 is expressed in the resistant strain than in the susceptible strain at concentrations of vancomycin between 4 and 8 mg/liter, a concentration range that is within that of the trough serum level during vancomycin therapy (5 to 15 mg/liter). This, of course, confounds our understanding of how PBP2 affects vancomycin resistance. However, if pbpB is not involved in vancomycin resistance, it is possible that the putative regulator of pbpB gene induction coregulates other genes involved in vancomycin resistance. Nevertheless, these data indicate that the putative factors that control vancomycin induction of the pbpB gene are altered in strain IL-F. Also, the fact that induction in strain IL-F was merely hampered, not abolished, suggests that at least two factors cooperate in vancomycin induction of pbpB gene expression and that one of these factors has been altered in some way in strain IL-F. The results from the gel retardation assay, in which the presence of both the P1 and P1′ promoters was required for enhanced binding of vancomycin-induced proteins to the pbpB promoter, is further evidence that the induction involves cooperative binding. Whether any of the regulatory genes that have been implicated in glycopeptide resistance are also involved in pbpB expression remains to be addressed (4, 29).

Of the other PBPs, a decrease in PBP4 (carboxypeptidase) (17, 45) and PBP2a (46) activity was found in VISA isolates, although the latter result has not been consistently found. For instance, isolates IL-A and IL-F express equivalent amounts of mecA (unpublished data) and are equally resistant to methicillin (5). A decrease in PBP4 activity would result in lower carboxypeptidase activity, which was proposed to explain the decrease in peptidoglycan cross-linking found in some VISA isolates. Such decreased cross-linking would result in an increase in the number of d-Ala-d-Ala termini on peptidoglycan stem peptides and thereby increase the false vancomycin-binding sites in the preformed cell wall. According to one model of vancomycin resistance (14), increased nonspecific binding to the cell wall presumably would lower the effective concentration of vancomycin that is able to reach its vital target, the peptidoglycan precursor, which is attached to the cell membrane (18). Challenging this model are the results of a study which used high-performance liquid chromatography of cell wall muramidase digestion products that demonstrated increased peptidoglycan cross-linking in VISA strains that included strain 523k (6) and clinical isolates IL-F and PC (7). Therefore, contrary to the model, these strains would actually have fewer d-Ala-d-Ala termini and fewer false binding sites for vancomycin. We speculate that the decrease in PBP4 activity observed in other VISA isolates is a compensatory response to the increased PBP2 production that balances the total cross-linking activity in the cell. Alternately, pbpB gene expression might be coordinately up-regulated by factors that decrease the expression of the pbpD gene that encodes PBP4.

Given the central role that PBP2 plays in cell wall metabolism and resistance to oxacillin and (perhaps) vancomycin and the finding that pbpB transcription is inducible by cell wall-active antibiotics, it is now of interest to identify the factors that control such pbpB gene induction. The difference in PBP2 expression between strains IL-A and IL-F was not due to changes in the cis-regulatory elements of the pbpB promoter region. Therefore, a change in transcription factor activity must be involved. The results of the gel shift assays support the view that such transcription factors are either induced by vancomycin or are in some way induced to have a greater affinity for the pbpB promoter.

It is well established that oxacillin induces the mecA gene that encodes PBP2a in MRSA isolates via the MecI repressor and the MecR1 signal-transducing protein (23) or by BlaI and BlaR1, a repressor and signal-transducing protein, respectively, that control β-lactamase gene expression (1). Increased expression of pbpB in response to oxacillin is therefore consistent with the recent discovery that PBP2 cooperates with PBP2a in peptidoglycan synthesis when oxacillin is present (37, 40). Thus, it is understandable that oxacillin simultaneously induces the pbpB and mecA genes to coordinate methicillin resistance. It is interesting that a β-lactam induces expression of a gene that encodes one of the eventual targets of this antibiotic, since increased PBP2 production can lead to borderline resistance. Future investigations may determine whether other classes of β-lactams are also capable of inducing PBP2 expression, whether other PBPs are also induced, and whether by inhibiting the induction it is possible to increase the effectiveness of β-lactams.

Our data, showing that methicillin-susceptible (mecA-negative) strains that also lacked β-lactamase were capable of inducing pbpB gene transcription in response to the presence of vancomycin and oxacillin, demonstrate that MecR1, BlaR1, MecI, and BlaI are not involved in the pbpB induction pathway.

From these data, we propose that pbpB expression is stimulated by vancomycin and oxacillin via a putative regulatory system other than MecRI/MecI or BlaR1/BlaI that does not require agr or SigB activity. The role of prfA is poorly understood. However, it does not appear to play a role in pbpB constitutive transcription (39), and its role in antibiotic induction has not yet been investigated. We speculate that since vancomycin does not enter the cell, it is possible that a signal-transducing mechanism is involved in pbpB gene induction. Alternately, since vancomycin and oxacillin are from unrelated classes of antibiotics, it is possible that the signal for pbpB gene activation results from the inhibition of cell wall synthesis, analogous to the system controlling AmpC β-lactamase gene induction in gram-negative bacteria (25).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Wolfgang Epstein for critical reading of the manuscript and Vasanthi Pallinti for technical assistance with Northern blotting of strains 523 and 523k. We also thank Keiichi Hiramatsu for sharing the VISA clinical isolate Mu50 and Richard Novick for providing strain RN6911.

S. Boyle-Vavra and R. S. Daum were supported by NIH R01 AI40481-01A1 (to R.S.D.) and R03 AI 44999-01 (to S.B.-V.) and by a grant from the Grant Healthcare Foundation (Lake Forest, Ill.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Berger-Bachi, B. 1999. Genetic basis of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 56:764-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger-Bachi, B., A. Strassle, and F. H. Kayser. 1986. Characterization of an isogenic set of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 5:697-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff, M., and B. Berger-Bächi. 2001. Teicoplanin stress-selected mutations increasing σB activity in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1714-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bischoff, M., M. Roos, J. Putnik, A. Wada, P. Glanzmann, P. Giachino, P. Vaudaux, and B. Berger-Bachi. 2001. Involvement of multiple genetic loci in Staphylococcus aureus teicoplanin resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 194:77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle-Vavra, S., R. B. Carey, and R. S. Daum. 2001. Development of vancomycin and lysostaphin resistance in a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:617-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle-Vavra, S., B. L. M. De Jonge, C. C. Ebert, and R. S. Daum. 1997. Cloning of the Staphylococcus aureus ddh gene encoding NAD+-dependent d-lactate dehydrogenase and insertional inactivation in a glycopeptide-resistant isolate. J. Bacteriol. 179:6756-6763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyle-Vavra, S., H. Labischinski, C. C. Ebert, K. Ehlert, and R. S. Daum. 2001. A spectrum of changes occurs in peptidoglycan composition of glycopeptide-intermediate clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:280-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Staphylococcus aureus resistant to vancomycin—United States, 2002. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:565-567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin—Illinois, 1999. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 48:1165-1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers, H. F. 1997. Methicillin resistance in staphylococci: molecular and biochemical basis and clinical implications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:781-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chambers, H. F., and C. Miick. 1992. Characterization of penicillin-binding protein 2 of Staphylococcus aureus: deacylation reaction and identification of two penicillin-binding peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:656-661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambers, H. F., M. J. Sachdeva, and C. J. Hackbarth. 1994. Kinetics of penicillin binding to penicillin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem. J. 301:139-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung, A. L., J. M. Koomey, S. Lee, E. A. Jaffe, and V. A. Fischetti. 1992. Regulation of exoprotein expression in Staphylococcus aureus by a locus (sar) distinct from agr. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6462-6466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui, L., H. Murakami, K. Kuwahara-Arai, H. Hanaki, and K. Hiramatsu. 2000. Contribution of a thickened cell wall and its glutamine nonamidated component to the vancomycin resistance expressed by Staphylococcus aureus Mu50. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2276-2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daum, R. S., S. Gupta, R. Sabbagh, and W. M. Milewski. 1992. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates with decreased susceptibility to vancomycin and teicoplanin: isolation and purification of a constitutively produced protein associated with decreased susceptibility. J. Infect. Dis. 166:1066-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diekema, D. J., M. A. Pfaller, F. J. Schmitz, J. Smayevsky, J. Bell, R. N. Jones, and M. Beach. 2001. Survey of infections due to Staphylococcus species: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific region for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997-1999. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32(Suppl. 2):S114-S132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finan, J. E., G. L. Archer, M. J. Pucci, and M. W. Climo. 2001. Role of penicillin-binding protein 4 in expression of vancomycin resistance among clinical isolates of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3070-3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geisel, R., F. J. Schmitz, A. C. Fluit, and H. Labischinski. 2001. Emergence, mechanism, and clinical implications of reduced glycopeptide susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:685-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giachino, P., S. Engelmann, and M. Bischoff. 2001. σB activity depends on RsbU in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:1843-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanaki, H., K. Kuwahara-Arai, S. Boyle-Vavra, R. S. Daum, H. Labischinski, and K. Hiramatsu. 1998. Activated cell-wall synthesis is associated with vancomycin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains Mu3 and Mu50. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42:199-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henze, U. U., and B. Berger-Bächi. 1995. Staphylococcus aureus penicillin-binding protein 4 and intrinsic β-lactam resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2415-2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiramatsu, K. 2001. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a new model of antibiotic resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 1:147-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiramatsu, K., K. Asada, E. Suzuki, K. Okonogi, and T. Yokota. 1992. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the regulator region of mecA gene in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). FEBS Lett. 298:133-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, K. Asada, N. Mori, K. Tsutsumimoto, C. Tiensasitorn, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Structural comparison of three types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec integrated in the chromosome in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1323-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs, C., J. M. Frere, and S. Normark. 1997. Cytosolic intermediates for cell wall biosynthesis and degradation control inducible beta-lactam resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Cell 88:823-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji, G., R. C. Beavis, and R. P. Novick. 1995. Cell density control of staphylococcal virulence mediated by an octapeptide pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:12055-12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katayama, Y., T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2000. A new class of genetic element, staphylococcus cassette chromosome mec, encodes methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1549-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Komatsuzawa, H., G. H. Choi, K. Ohta, M. Sugai, M. T. Tran, and H. Suginaka. 1999. Cloning and characterization of a gene, pbpF, encoding a new penicillin-binding protein, PBP2B, in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1578-1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuroda, M., K. Kuwahara-Arai, and K. Hiramatsu. 2000. Identification of the up- and down-regulated genes in vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains Mu3 and Mu50 by cDNA differential hybridization method. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 269:485-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma, X. X., T. Ito, C. Tiensasitorn, M. Jamklang, P. Chongtrakool, S. Boyle-Vavra, R. S. Daum, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Novel type of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec identified in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1147-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahmood, R., and S. A. Khan. 1990. Role of upstream sequences in the expression of the staphylococcal enterotoxin B gene. J. Biol. Chem. 265:4652-4656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mainardi, J. L., D. M. Shlaes, R. V. Goering, J. Shlaes, J. F. Acar, and F. W. Goldstein. 1995. Decreased teicoplanin susceptibility of methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1646-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreira, B., S. Boyle-Vavra, B. L. M. DeJonge, and R. S. Daum. 1997. Increased production of penicillin-binding protein 2, increased detection of other penicillin-binding proteins, and decreased coagulase activity associated with glycopeptide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1788-1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakami, K., T. Fujimura, and M. Doi. 1994. Nucleotide sequence of the structural gene for the penicillin-binding protein 2 of Staphylococcus aureus and the presence of a homologous gene in other staphylococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 117:131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novick, R. P., H. F. Ross, S. J. Projan, J. Kornblum, B. Kreiswirth, and S. Moghazeh. 1993. Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 12:3967-3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedersen, L. B., and P. Setlow. 2000. Penicillin-binding protein-related factor A is required for proper chromosome segregation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:1650-1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinho, M. G., H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 2001. An acquired and a native penicillin-binding protein cooperate in building the cell wall of drug-resistant staphylococci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 21:21.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinho, M. G., H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 2000. Cloning, characterization, and inactivation of the gene pbpC, encoding penicillin-binding protein 3 of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 182:1074-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinho, M. G., H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 1998. Transcriptional analysis of the Staphylococcus aureus penicillin binding protein 2 gene. J. Bacteriol. 180:6077-6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinho, M. G., A. M. Ludovice, S. Wu, and H. De Lencastre. 1997. Massive reduction in methicillin resistance by transposon inactivation of the normal PBP2 in a methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Drug Resist. 3:409-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piriz Duran, S., F. H. Kayser, and B. Berger-Bachi. 1996. Impact of sar and agr on methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 141:255-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Popham, D. L., and P. Setlow. 1996. Phenotypes of Bacillus subtilis mutants lacking multiple class A high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178:2079-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reynolds, P. E., and D. F. J. Brown. 1985. Penicillin-binding proteins of β-lactam-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus: effects of growth conditions. FEBS Lett. 192:28-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shlaes, D. M., J. H. Shlaes, S. Vincent, L. Etter, P. D. Fey, and R. V. Goering. 1993. Teicoplanin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus expresses a novel membrane protein and increases expression of penicillin-binding protein 2 complex. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:2432-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sieradzki, K., M. G. Pinho, and A. Tomasz. 1999. Inactivated pbp4 in highly glycopeptide-resistant laboratory mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18942-18946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sieradzki, K., S. W. Wu, and A. Tomasz. 1999. Inactivation of the methicillin resistance gene mecA in vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Drug Resist. 5:253-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spratt, B. G. 1983. Penicillin-binding proteins and the future of β-lactam antibiotics. J. Gen. Microbiol. 129:1247-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stevens, D. L., S. Yan, and A. E. Bryant. 1993. Penicillin-binding protein expression at different growth stages determines penicillin efficacy in vitro and in vivo: an explanation for the inoculum effect. J. Infect. Dis. 167:1401-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomasz, A., H. B. Drugeon, H. M. de Lencastre, D. Jabes, L. McDougall, and J. Bille. 1989. New mechanism for methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: clinical isolates that lack the PBP 2a gene and contain normal penicillin-binding proteins with modified penicillin-binding capacity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:1869-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wada, A., and H. Watanabe. 1998. Penicillin-binding protein 1 of Staphylococcus aureus is essential for growth. J. Bacteriol. 180:2759-2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]