Abstract

Human integrin α5 was transfected into the integrin α5/β1–negative intestinal epithelial cell line Caco-2 to study EGF receptor (EGFR) and integrin α5/β1 signaling interactions involved in epithelial cell proliferation. On uncoated or fibronectin-coated plastic, the integrin α5 and control (vector only) transfectants grew at similar rates. In the presence of the EGFR antagonistic mAb 225, the integrin α5 transfectants and controls were significantly growth inhibited on plastic. However, when cultured on fibronectin, the integrin α5 transfectants were not growth inhibited by mAb 225. The reversal of mAb 225–mediated growth inhibition on fibronectin for the integrin α5 transfectants correlated with activation of the EGFR, activation of MAPK, and expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen. EGFR kinase activity was necessary for both MAPK activation and integrin α5/β1–mediated cell proliferation. Although EGFR activation occurred when either the integrin α5–transfected or control cells were cultured on fibronectin, coprecipitation of the EGFR with SHC could be demonstrated only in the integrin α5–transfected cells. These results suggest that integrin α5/β1 mediates fibronectin-induced epithelial cell proliferation through activation of the EGFR.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial cells receive important cues from the environment through soluble growth factors and insoluble extracellular matrix proteins. The receptors chiefly responsible for this binding are the growth factor receptors and integrins, respectively. The signaling triggered by these receptors effect changes in critical cell functions as diverse as proliferation, differentiation, and survival (Pignatelli and Bodmer, 1989; Streuli et al., 1991; Roskelley et al., 1994; Sastry et al., 1996; Giancotti, 1997; Somasiri and Roskelley, 1999). With regard to cell cycle progression and proliferation, coordinated input from both growth factor receptors and integrins is necessary (Clark and Brugge, 1995; Zhu and Assoian, 1995, 1996; Wary et al., 1996, 1998; Schwartz and Baron, 1999).

How growth factor and integrin signal transduction pathways are actually integrated in controlling cell functions is not well understood. Most studies have used mesenchymal cells and boluses of exogenous growth factors to stimulate growth factor receptor activity. Such acute conditions are not usually found in normal tissue. Epithelial cells are usually regulated by autocrine growth factor loops (Ferriola et al., 1991, 1992; Bishop et al., 1995; Damstrup et al., 1999). Autocrine growth factor activation of the EGF receptor (EGFR) is best described as a steady-state system as it approximates normal cell physiology in vivo (Wiley and Cunningham, 1981). Epithelial cells would rarely be exposed in vivo to acute and large concentrations of growth factors. In addition, the exposure of cells to boluses of EGF family growth factors usually results in only transient activation of the EGFR. The use of epithelial cells is clinically relevant in that they are the frequent targets of diseases, such as adenocarcinoma, in which aberrant growth is a characteristic finding.

Both integrins and the EGFR activate common members of the RAS-ERK signal transduction pathway (Pages et al., 1993; Chen et al., 1994; Lange-Carter and Johnson, 1994; Kelleher et al., 1995; Morino et al., 1995; Zhu and Assoian, 1995, 1996; Miyamoto et al., 1996). Growth factor–induced cell proliferation is mediated by the MAPKs, also known as extracellular signal–regulated kinases (ERKs) (Pages et al., 1993; Aliaga et al., 1999). Although integrins and the EGFR can activate ERK independently, the emerging picture is that ERK activation must exceed a threshold to drive cell proliferation. Exceeding this threshold requires input from both integrins and growth factor receptors (Zhu and Assoian, 1995, 1996; Schwartz and Baron, 1999). How integrin and growth factor receptor signaling are integrated proximal to ERK is not well understood.

At present, there are three known mechanisms by which integrins can activate ERKs, and all three mechanisms involve RAS as the activator of downstream MAPKs. The first mechanism is through the activation of Fyn by Shc, which is initially recruited by activated integrins via caveolin (Wary et al., 1998). Interestingly, although integrins α1, α2, α3, α5, and αV interact with caveolin, only α1/β1, α5/β1, or αV can recruit Shc and activate Fyn (Wary et al., 1996, 1998). Shc then recruits Grb2 and SOS, the latter of which activates the RAS-ERK pathway. The second mechanism of ERK activation is through integrin-mediated focal adhesion kinase activation, which results in the recruitment of Grb2 (Schlaepfer et al., 1994, 1998; Hanks and Polte, 1997), which in turn recruits SOS and consequently leads to RAS activation. The third mechanism is integrin-mediated EGFR activation (Moro et al., 1998; Li et al., 1999), which also causes activation of Shc, Grb2, and RAS.

Epithelial cells express a large repertoire of various integrin receptors, and the redundancy of specific extracellular matrix proteins bound by these integrins complicates investigation. However, integrin α5/β1 possesses high-affinity binding only to fibronectin (Hemler, 1990). The Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cell line used lacks detectable expression of the classic fibronectin receptor, integrin α5/β1, and EGFR expression and function have been characterized extensively in this cell line (Hidalgo et al., 1989; Bishop and Wen, 1994; Bishop et al., 1995; Tong et al., 1998; Kuwada et al., 1999). Although adding EGF family ligands, such as EGF, does not greatly stimulate Caco-2 cell proliferation, interrupting autocrine EGF family growth factor activation of the EGFR can diminish cell proliferation significantly (Damstrup et al., 1999; Kuwada et al., 1999). Caco-2 cells were transfected with integrin α5 to study signaling interactions between integrin α5/β1 and the EGFR that are involved in the control of epithelial cell proliferation.

We asked specifically whether integrin α5/β1–mediated EGFR activation occurs in epithelial cells and what role this plays in cell proliferation. We found that integrin α5/β1 mediates fibronectin-induced EGFR activation, which leads to EGFR-mediated activation of MAPKs and cell proliferation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and Kinase Inhibitors

Antibodies used were integrin α2 mAb (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ); integrin α3 mAb (Becton-Dickinson); integrin αV mAb, phosphoserine mAb, EGFR mAb, rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Zymed, San Francisco, CA); integrin α5 subunit (mAb 16, Becton-Dickinson; and polyclonal antibody, Chemicon); PY-20 mAb, phospho-p44/42 MAPK E10 mAb, Shc polyclonal antibody, Grb2 mAb, ERK1 mAb, MEK1, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) mAb (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY); and alkaline phosphatase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). The MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) and the EGFR kinase inhibitor Compound 32 (PD 153035; Calbiochem) were solubilized in DMSO.

Integrin α5 Gene Construct

The human integrin α5 gene (in the plasmid pECE) was obtained as a generous gift from Dr. Erkki Ruoslahti. The SalI–XbaI fragment encompassing the integrin α5 gene was cloned into the XhoI and XbaI sites of the vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), which has a G418 resistance gene.

Cell Lines, Tissue Culture, and Transfection

Caco-2 cells were obtained as a gift from Dr. Robert J. Coffey, Jr., and maintained in DMEM (ICN Biomedical, Costa Mesa, CA) supplemented with fibronectin-free 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT), glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin in a 37°C humidified tissue culture incubator with a 5% CO2 environment. The cells were cultured on uncoated or fibronectin-coated (10 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) 35-mm bacterial plastic dishes (Falcon), 35-mm tissue culture dishes (Greiner), and 96-well tissue culture plastic dishes (Greiner). When mAb 225 (Imclone) and integrin mAb (Becton-Dickinson) were used, they were mixed with dispersed cells to a final concentration of 10 and 5 μg/ml, respectively, just before cell plating. Compound 32 (PD 153035), solubilized in DMSO, was added to cell culture medium to achieve a final concentration of 4 μM (controls received an equal concentration of DMSO alone).

Caco-2 cells were transfected with the pcDNA3 vector alone or with the human integrin α5–pcDNA3 construct by a calcium phosphate method. Caco-2 cells between passages 90 and 95 were grown to ∼70% confluence on 100-mm dishes. Ten to 40 μg of plasmid DNA preparations (Wizard Preparations, Promega, Madison, WI) were added to sterile 1× TE buffer to a total volume of 500 μL. Fifty microliters of sterile 2.5 M CaCl2 in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2 was added to the plasmid DNA and mixed thoroughly. The calcium-DNA solution was then dripped into 0.5 ml of sterile 2× HEBS buffer with vigorous mixing every three drops. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The entire mixture was then added to the 10 ml of culture medium bathing the cells. The medium was aspirated off the next day, the cells were washed twice with PBS-EDTA, and fresh medium was added. Forty-eight hours after the transfection procedure, the cells were dispersed in trypsin and replated in 10 ml of medium containing 1.5 mg/ml G418 (LD curves demonstrated that a G418 final concentration of at least 1.2 mg/ml was needed to kill all Caco-2 cells in culture). Approximately 25–30 cell colonies were obtained, and the individual clones were removed with trypsin with the use of cloning cylinders (Bellco). The individual colonies were plated on 12-well plates in medium containing 1.5 mg/ml G418. Once confluent colonies were obtained in 12-well plates, the cells were replated on 10-cm dishes. During all steps, the cell culture medium was exchanged every 2 d.

For the soft agar proliferation assay, a 1.6% low-melting-point agar solution (in water) was microwaved until boiling and then cooled in a 37°C water bath. The agar solution was mixed 1:1 with 2× medium, and 1 ml of this solution was plated in 35-mm tissue culture plastic dishes. A total of 20,000 cells were added to a solution containing 2× medium and 1× medium in a 1:2 ratio (3 ml total volume per dish). Then, 1 ml of liquid 1.6% agar solution (at 37°C) was added to the cell mixture, which was vortexed gently to disperse the cells. One milliliter of the cell mixture was layered onto the bottom of the dish and left at room temperature until the agar solidified. The cells were placed in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 and photographed each day.

Expression of Integrins by Caco-2 Cells

Flow cytometry and immunoblotting were used to evaluate cells for the expression of various integrins. For flow cytometric analysis of integrin expression, cells were dispersed in 0.25% trypsin in PBS-EDTA and washed twice in PBS-EDTA. The cells were then mixed at 37°C with integrin α5 mAb (Becton-Dickinson) at a dilution of 1:500 in blocking buffer A (1% radioimmunoassay-grade BSA [Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA] in PBS) for 60 min. The cells were washed twice in blocking buffer A, mixed with a 1:1000 dilution of FITC-labeled rabbit anti-mouse mAb (Jackson Immunoresearch) in blocking buffer A, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The cells were washed twice in PBS-EDTA and assayed with a flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson). Integrin expression was determined to be the percentage of FITC-positive cells. The gate setting was determined by the fluorescence intensity of the same cells stained with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody only.

For immunodetection of integrin α5 expression, cells were cultured for 2 d on plastic dishes and then prepared according to the immunoprecipitation protocol described below. For immunoprecipitation, 2 μg of integrin α5 mAb (Becton-Dickinson) was added to each tube of lysate, and the primary antibody used for immunodetection was integrin α5 polyclonal antibody (Chemicon) used at a 1:1000 dilution in blocking buffer B.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunodetection

For immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in 4°C lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 100 mM NaF, 10 mM Na2PO4, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, and 1 μg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin, chymostatin, and pepstatin) and clarified at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 15 min. The lysates were then normalized for protein concentration to a total volume of 1 ml in lysis buffer. Antibody (1–2 μg) was added to each tube of lysate, which was then incubated on a rocker at 4°C for 2 h. The antibodies were immunoprecipitated with 50 μl of a slurry of protein A/G–Sepharose beads (Calbiochem) for 1 h on a rocker at 4°C. The beads were washed twice with lysis buffer and then boiled in sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 10 μg/ml bromphenol blue) for 3 min. The beads were pelleted by brief centrifugation, and the supernatants were loaded on SDS-PAGE gels (7.5 or 10% acrylamide). The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and then incubated in blocking buffer B (1% BSA [Bio-Rad], 100 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 0.9% NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet) overnight at 4°C.

For immunodetection, the blocked blots were probed with primary antibody for 2 h at 4°C on a rocker. The blots were washed twice for 10 min each in blocking buffer B and then incubated with a 1:2000 dilution of a rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibody (for monoclonal primary antibodies). After two washes in blocking buffer B, the blots were finally incubated either with a 1:5000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase–conjugated rabbit anti-mouse antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) or 50 ng/ml 125I-protein A in blocking buffer B. Alkaline phosphatase was detected by a colorimetric reaction with the use of a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium kit (Zymed). 125I-protein A–labeled blots were detected with the use of a Molecular Imager FX (Bio-Rad).

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cells were dispersed and plated at 40,000 cells per well in 96-well dishes. At various days in culture, the cells were gently washed twice with 100 μl per well of ice-cold blocking buffer A and twice with 100 μl per well of ice-cold PBS. The cells were fixed for 10 min in 100% ice-cold methanol (100 μl per well) and then allowed to air-dry. The cells were stained with 100 μl per well of 0.1% crystal violet in water for 10 min and then washed gently four times with double-distilled water and four times with PBS. The plates were then air-dried completely. The stained cells were solubilized in 1% sodium deoxycholate, and the plates were read at 590 nm in a spectrophotometer. The absorption at 590 nm is proportional to the number of attached cells (our unpublished results).

Signal Transduction

Cells were incubated in cell culture medium supplemented with mAb 225 (10 μg/ml final concentration), mAb integrin α5 (Becton-Dickinson; 5 μg/ml final concentration), PD 98059 (20–100 μM final concentration), or Compound 32 (4 μM final concentration) for various numbers of days. The degree of activation for immunoprecipitated EGFR, Shc, and Grb2 proteins was determined by immunodetection of antiphosphotyrosine with PY-20 mAb (1:2000 dilution in blocking buffer B; see Immunoprecipitation and Immunodetection for details). Activation of ERK1 and ERK2 was determined by immunodetection of cell lysates with phospho-MAPK E10 mAb (1:2000 dilution in blocking buffer B). Activation of MEK1 was determined by immunodetection of MEK1 immunoprecipitates with phosphoserine mAb (1:1000 dilution in blocking buffer B). Loading control experiments were performed by immunodetection of immunoprecipitates or lysates with EGFR mAb (1:500 dilution in blocking buffer B), Shc polyclonal antibody (1:5000 dilution in blocking buffer B), Grb2 mAb (1:2000 dilution in blocking buffer B), ERK1 mAb (1:2000 dilution in blocking buffer B), and MEK1 mAb (1:1000 dilution in blocking buffer B). PCNA expression was determined by immunodetection of cell lysates with PCNA mAb (1:5000 dilution in blocking buffer B).

RESULTS

Expression of Integrins in Caco-2 Cells

Caco-2 cells expressed integrins α2, α3, α4, β1, β3, β4, and αV, but not α5, by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (our unpublished results). Flow cytometry with two different mAbs raised against the human α5 integrin subunit failed to detect α5 integrin subunit expression in Caco-2 cells (Figure 1A, left panel), whereas another colonic epithelial cell line, SW-620, was positive for integrin α5 expression by flow cytometry (Figure 1A, right panel).

Figure 1.

(A) Flow cytometry of Caco-2 and SW-620 cells demonstrating integrin α5 expression (gray areas). (B) Flow cytometry of Caco-2 cell lines, A105 and A9, stably transfected with integrin α5 (gray areas). The cells were stained with an integrin α5 mAb and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies or with FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse antibodies alone (controls; unshaded areas). The ordinate represents the number of cells counted (in thousands) and the abscissa the fluorescein intensity. (C) Immunoblots of integrin α5 immunoprecipitates from Caco-2 cells stably transfected with vector alone (B6 and B7) and integrin α5. A single ∼120-kDa band (arrow), corresponding to the heavy chain of integrin α5, was obtained under reducing conditions. (D) Integrin α3, α4, and αV subunit expression in the control and integrin α5–transfected cells determined by flow cytometry. The transfectants were stained with integrin α3, α4, and αV mAbs followed by FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies. For each integrin subunit, the fluorescence intensity was expressed as a percentage of the controls (stained with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies alone).

Caco-2 cells were transfected with the human integrin α5 subunit or vector alone (controls). Two stable integrin α5 transfectants (A105 and A9) and two stable control transfectants (B6 and B7) were isolated after selection in G418 and used in all subsequent experiments. Integrin α5 expression was confirmed in the transfectants by flow cytometry (Figure 1B) and Western blot analysis of integrin α5 immunoprecipitates (Figure 1C). Because other integrin receptor subunits are involved in fibronectin binding (α3/β1, α4/β1, and αV), the expression of integrin α3, α4, and αV was compared between the integrin α5 transfectants and control cells by flow cytometry (Figure 1D). The integrin α5 transfectants and control cells expressed the integrin α3, α4, and αV subunits at similar levels except for clone B6, which expressed lower levels of integrin αV, which probably represents minor clonal variation.

Fibronectin Overcomes Inhibition of EGFR-mediated Cell Proliferation

Autocrine growth factor signaling by the EGFR has been shown to be important in Caco-2 cell proliferation. We have shown that exogenously applied EGF family growth factors have little effect on Caco-2 cell proliferation. This may be because the cells already express EGF family ligands (amphiregulin, TGFα, EGF, and HB-EGF). (Damstrup et al., 1999; Kuwada et al., 1999). However, incubating Caco-2 cells with EGFR-blocking antibodies significantly reduces cell proliferation by interrupting autocrine growth factor binding (Damstrup et al., 1999; Kuwada et al., 1999).

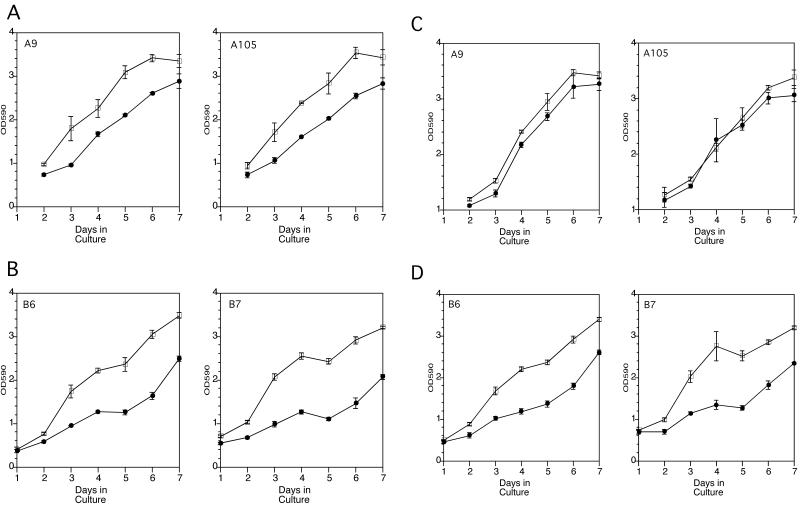

The Caco-2 integrin α5 transfectants grew at similar rates as the control cells on plastic (Figure 2, A and B) or fibronectin-coated plastic (Figure 2, C and D). In the absence of exogenous fibronectin, both the integrin α5 transfectants (Figure 2A) and control cells (Figure 2B) demonstrated significant inhibition of cell proliferation in the presence of 10 μg/ml of the antagonistic EGFR mAb 225, which inhibits ligand binding to the EGFR, resulting in diminished EGFR tyrosine kinase activity (Gill et al., 1984). On fibronectin-coated plastic, however, the integrin α5 transfectants grew at nearly the same rate in the absence or presence of mAb 225 (Figure 2C). In contrast, the control cells were growth inhibited to a similar degree by mAb 225 on uncoated or fibronectin-coated plastic (Figure 2, compare B and D). In addition, mAb 225 inhibited fibronectin-induced expression of the cell cycle protein PCNA in the control cells but not in the integrin α5–transfected cells at d 2 in culture (Figure 3). Thus, the inhibition of autocrine EGFR-mediated cell cycle progression and proliferation was overcome in the integrin α5/β1–expressing cells in the presence of exogenous fibronectin. This ability of the integrin α5/β1–expressing cells to overcome EGFR inhibition appeared to occur early during the 7-d cell proliferation studies when the Caco-2 cells were subconfluent. This may reflect more of a role for integrin α5/β1–mediated cell proliferation when Caco-2 cells are rapidly proliferating and not yet fully differentiated.

Figure 2.

Proliferation assays of control and integrin α5–transfected cells on plastic in the presence (●) or absence (□) of mAb 225. (A) Integrin α5–transfected cells cultured on plastic. (B) Control cells cultured on plastic. (C) Integrin α5–transfected cells cultured on fibronectin-coated plastic. (D) Control cells cultured on fibronectin-coated plastic. Cell counts were estimated with the use of a crystal violet staining method. The ordinate represents the optical density at 590 nm and the abscissa the number of days in culture. Cells were plated at 50,000 cells per well in 96-well plates at day 0. Each data point represents the average ± SEM of triplicate experiments.

Figure 3.

Immunoblot of PCNA performed on lysates of control and integrin α5–transfected cells cultured for 2 d on uncoated or fibronectin (Fn)-coated plastic in the absence of presence of mAb 225 (10 μg/ml). All lanes represent equal total protein concentrations.

To determine whether EGFR kinase activity was essential to the ability of the integrin α5–transfected cells to overcome mAb 225–mediated growth inhibition on fibronectin, we performed parallel proliferation studies with the use of the tyrphostin Compound 32. Compound 32 directly inhibits EGFR tyrosine kinase activity by competing for the ATP-binding site. Compound 32, used at a final concentration of 4 μM, caused a significant inhibition of cell proliferation for the integrin α5–transfected (Figure 4A) and control (Figure 4B) cells on plastic and inhibited EGFR autophosphorylation (our unpublished results). Unlike the case for mAb 225, culturing the integrin α5–transfected cells on fibronectin-coated plastic could not reverse the growth inhibition caused by compound 32 (Figure 4A). These results suggested that EGFR kinase activity was necessary for the integrin α5–transfected cells to overcome mAb 225–mediated growth inhibition in the presence of fibronectin. This implied that fibronectin might induce EGFR activation.

Figure 4.

Proliferation assays of control and integrin α5–transfected cells cultured on uncoated or fibronectin-coated plastic in the presence or absence of 4 μM Compound 32. (A) Integrin α5–transfected cells cultured on plastic without (□) and with (▵) Compound 32 or on fibronectin without (●) and with (♦) Compound 32. (B) Control cells cultured on plastic without (□) and with (▵) Compound 32 or on fibronectin without (●) and with (♦) Compound 32. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM for experiments performed in triplicate.

Integrin α5/β1–mediated Activation of the EGFR

Recent reports showed that the EGFR could be activated by integrin-mediated fibronectin binding (Moro et al., 1998), even in the absence of growth factors (Li et al., 1999). Therefore, we examined whether the EGFR was activated by adhesion to fibronectin in the integrin α5–transfected and control cells. We found that the EGFR was activated in both the control and integrin α5–transfected cells when adhered to fibronectin but not to plastic (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Control (B6) and integrin α5–transfected (A105) cells were cultured for 2 d on uncoated or fibronectin-coated plastic in the presence or absence of mAb 225 (10 μg/ml). Immunoprecipitates of EGFR, Shc, and Grb2 were obtained from lysates normalized for total protein and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was then performed. (A) Phosphotyrosine (top panels) and EGFR (bottom panels) immunoblots of EGFR immunoprecipitates. (B) Phosphotyrosine (top panels) and Shc (bottom panels) immunoblots of Shc immunoprecipitates. (C) Phosphotyrosine (top panels) and Grb2 (bottom panels) immunoblots of Grb2 immunoprecipitates.

The EGFR can activate Shc and Grb2, signaling proteins important in EGFR-mediated cell proliferation (Rozakis-Adcock et al., 1993; Sasaoka et al., 1994). Thus, we examined their levels of tyrosine phosphorylation in the control and integrin α5–transfected cells (Figure 5, B and C). The levels of tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc and Grb2 were similar between the integrin α5 transfectants and controls.

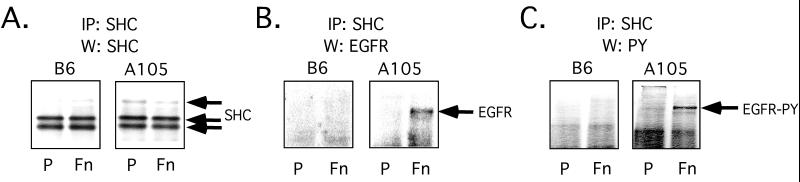

Although the levels of tyrosine phosphorylation of total cellular Shc protein were similar under the various conditions, only a small proportion of total cellular Shc may be recruited by activated EGFR. Therefore, the levels of EGFR protein associated with Shc were studied in the control and integrin α5–transfected cells. The control and integrin α5 transfectants were grown on either uncoated or fibronectin-coated plastic for 2 d and then lysed. The presence of EGFR protein, tyrosine phosphorylated EGFR, and Shc protein was detected in Shc immunoprecipitates. Although Shc was immunoprecipitated from all the cell lysates under the various conditions at equal levels (Figure 6A, left panel), EGFR protein coprecipitated with Shc only in the integrin α5–transfected cells cultured on fibronectin-coated plastic (Figure 6B, right panel). Furthermore, EGFR protein that coprecipitated with Shc in the integrin α5–transfected cells was tyrosine phosphorylated (Figure 6C, right panel), which is consistent with previous reports that Shc binds only to activated EGFR (Pelicci et al., 1992; Ruff-Jamison et al., 1993; Sasaoka et al., 1994). Thus, the interaction of Shc with the EGFR was exclusive to the integrin α5 transfectants that were cultured on fibronectin.

Figure 6.

Shc (A), EGFR (B), and phosphotyrosine (C) immunoblots were performed on Shc immunoprecipitates from control and integrin α5–transfected cells grown for 2 d on uncoated (P) or fibronectin-coated (Fn) plastic. Shc immunoprecipitation was performed on the different lysates that had been normalized for total protein. Each of the immunoprecipitates was then divided into three aliquots, which were used to generate the different immunoblots in A, B, and C. Panel A shows that equal amounts of Shc were immunoprecipitated from the different cell lysates.

Integrin α5/β1 and EGFR-mediated MAPK Activation

Activated EGFR and integrin α5/β1 can recruit both Shc and Grb2. Grb2 then recruits SOS, which activates RAS and leads to the recruitment of Raf to the cell membrane. Raf then activates MEK1, which in turn activates ERK1 and ERK2. Because MAPKs are important mediators of growth factor–induced cell proliferation (Pages et al., 1993; Cowley et al., 1994), we examined the ability of integrin α5/β1 to activate ERK1 and ERK2.

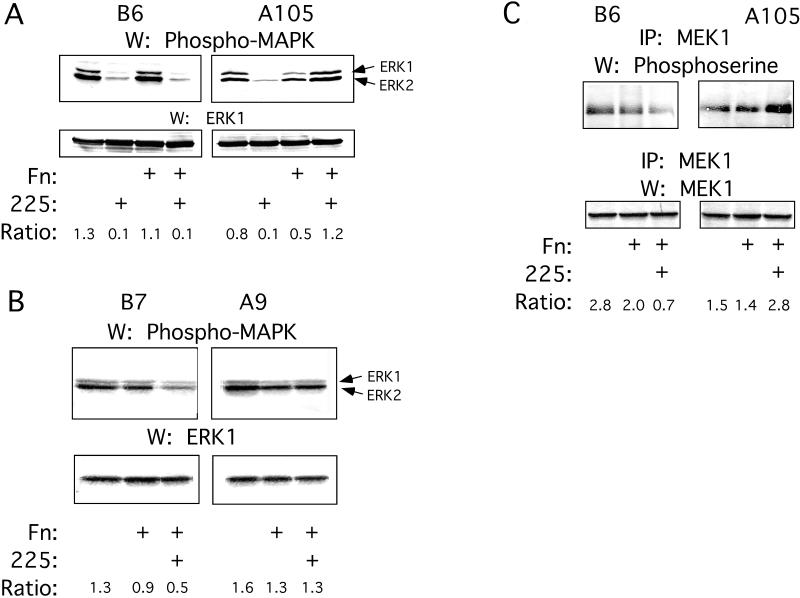

Integrin α5–transfected and control cells were cultured on uncoated or fibronectin-coated plastic dishes in the absence or presence of mAb 225 for 8 d. At various times from 2 to 8 d in culture, the cells were lysed and Western blots with an activated MAPK mAb were performed. Between 2 and 5 d in culture, significant differences in constitutive MAPK activation were seen between integrin α5–transfected and control cells. When the control cells were cultured on uncoated or fibronectin-coated plastic, the activation of ERK1 and ERK2 was significantly inhibited in the presence of mAb 225 (Figure 7A, top left panel). Constitutive ERK1 and ERK2 activation in the integrin α5 transfectants grown on plastic was inhibited by mAb 225 (Figure 7A, top right panel). However, when the integrin α5–transfected cells were cultured on fibronectin-coated plastic, ERK1 and ERK2 constitutive activation levels were not decreased by the presence of mAb 225 (Figure 7A, top right panel).

Figure 7.

Control (B6 and B7) and integrin α5–transfected (A105 and A9) cells were cultured on uncoated or fibronectin-coated plastic in the presence or absence of mAb 225 for 2–4 d, after which they were lysed and normalized for total protein. (A) Immunoblots of phospho-MAPK (top panels) and ERK1 (bottom panels) were made from clones B6 and A105. Arrows indicate phosphorylated ERK1 and ERK2, both of which were detected by the phospho-MAPK mAb. (B) Immunoblots of phospho-MAPK (top panels) and ERK1 (bottom panels) were made from clones B7 and A9. (C) Immunoblots of phosphoserine (top panels) and MEK1 (bottom panels) were made from MEK1 immunoprecipitates from clones B6 and A105. Densitometry results of the bands are reported as ratios of the band densities of phospho-MAPK or phosphoserine to the respective loading controls.

Similarly, constitutive ERK1 and ERK2 activation was inhibited by mAb 225 in the control cell line B7, but not in the integrin α5–transfected cell line A9, when they were cultured on fibronectin (Figure 7B). When the integrin α5–transfected and control cells were cultured on fibronectin in the presence of mAb 225 and an antifunctional integrin α5 mAb, ERK1 and ERK2 activation was unchanged in the control cells but was inhibited in the integrin α5 transfectants (our unpublished results). This demonstrated that the integrin α5/β1–fibronectin interaction was specifically responsible for the activation of ERK1 and ERK2 in the integrin α5 transfectants in the presence of mAb 225.

Because MEK1 activates ERK1 and ERK2, we examined MEK1 activation. Activated (serine-phosphorylated) MEK1 was detected when the control cells (Figure 7C, top left panel) and integrin α5 transfectants (Figure 7C, top right panel) were cultured on uncoated or fibronectin-coated plastic. However, when the cells were cultured on fibronectin-coated plastic in the presence of mAb 225, activated MEK1 was not detected in the control cells (Figure 7C, top left panel) but was detected in the integrin α5 transfectants (Figure 7C, top right panel).

To determine whether MAPK activation was important to cell proliferation, the integrin α5 transfectants and controls were grown on fibronectin-coated or uncoated plastic in the presence or absence of the MEK inhibitor PD98059 for 8 d. In the presence of 50 or 100 μM PD98059, the growth of the control cells and integrin α5 transfectants was significantly inhibited on plastic and fibronectin (our unpublished results). Treatment of the control cells and integrin α5 transfectants with PD98059 (20 μM) significantly decreased ERK1 and ERK2 activation (our unpublished results). These results demonstrated the overall importance of ERK1 and ERK2 activation to the proliferation of the integrin α5 transfectants and control cells.

To determine whether EGFR kinase activity was necessary for ERK1 and ERK2 activation, the integrin α5–transfected and control cells were grown in the presence of Compound 32 for 48 h, after which ERK1 and ERK2 activation were determined. For both the integrin α5–transfected and control cells, Compound 32 resulted in the near-total inhibition of activated ERK1 and ERK2 in the presence or absence of fibronectin (our unpublished results).

These data suggested that ERK1 and ERK2 activation was dependent on the following: 1) EGFR kinase activity in both the integrin α5–transfected and control cells, and 2) autocrine EGFR activation in the control cells but not in the integrin α5–transfected cells.

Because focal adhesion kinase (FAK) could potentially mediate integrin activation of MAPK, FAK tyrosine phosphorylation was also studied in the transfectants. No significant differences in FAK tyrosine phosphorylation were seen for the control or integrin α5–expressing cells cultured on plastic or fibronectin-coated plastic in the absence or presence of mAb 225 (our unpublished results).

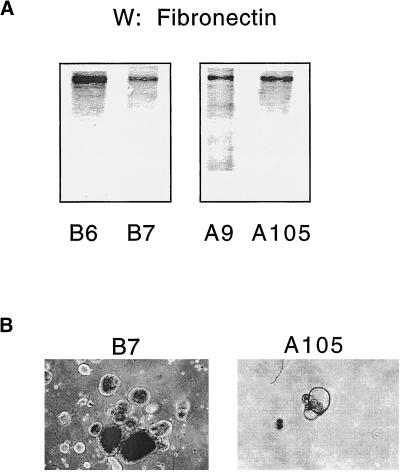

Anchorage-independent Proliferation

A previous study showed that the expression of integrin α5 in the HT-29 colon cell line resulted in growth inhibition in the absence of exogenous fibronectin (Varner et al., 1995). There was no growth arrest in the integrin α5–transfected versus control Caco-2 cell lines in the absence of fibronectin. This may have been due to the fact that Caco-2 cells express fibronectin (Figure 8A) and HT-29 cells reportedly do not. Our results seemed paradoxical in that although the integrin α5–transfected cells expressed endogenous fibronectin, the reversal of mAb 225–mediated growth inhibition could occur only in the presence of exogenous fibronectin. Most of the endogenous fibronectin protein recovered from the Caco-2 transfectants was associated with the cells themselves (our unpublished results). The exogenous fibronectin was presented to the cells on a fixed, rigid, and planar surface. It has been reported that exogenous fibronectin results in more robust cell adhesion in human epithelial cells (Wang et al., 1999). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that extracellular matrix substrates can elicit completely different cellular responses depending on whether they are presented to cells in a rigid or malleable form (Bissell and Guzelian, 1980; Bissell et al., 1987; Ben-Ze'ev et al., 1988; Garcia et al., 1999). This may be due to the ability of a rigid extracellular matrix to provide forces of tension to cellular structures, which can effect specific signal transduction activity (Miyamoto et al., 1995, 1998). Fibronectin deposited on the cell surface or presented to the cell in its malleable form, on the other hand, cannot provide fixed points against which cellular structures can be anchored and tensioned.

Figure 8.

(A) Fibronectin immunoblot of control (B6 and B7) and integrin α5–transfected (A9 and A105) cell lines cultured on plastic for 4 d. (B) Photomicrographs (×40) of control (B7) and α5–transfected (A105) cell lines grown in soft agar for 6 d. Cells were seeded at the same density on d 1, and the assays were performed in triplicate.

To study this, we cultured the Caco-2 transfectants in soft agar in which any endogenous fibronectin could not be deposited as a rigid extracellular matrix. In soft agar, the integrin α5–transfected cells were growth inhibited compared with the control cells (Figure 8B). These results are similar to those in HT-29 colonic epithelial cells expressing integrin α5/β1 (Varner et al., 1995). Interestingly, the shape of Caco-2 cells cultured in soft agar is round (Figure 8B), although they become columnar when cultured on a rigid surface (Hidalgo et al., 1989). Cell shape is important in determining cell proliferation (Folkman and Moscona, 1978), and integrin–extracellular matrix interactions are important transducers of changes in cell shape (Ingber, 1990). It appears that although Caco-2 cells express fibronectin, only fibronectin presented to the cell as a rigid substrate can stimulate cell proliferation, presumably by both clustering and activating fibronectin receptors. Thus, Caco-2 cells transfected with integrin α5 are capable of depositing fibronectin on plastic, which may be sufficient to prevent integrin α5/β1–mediated growth inhibition in these cells.

DISCUSSION

Expression of human integrin α5 in Caco-2 cells resulted in significant differences in Caco-2 cell proliferation and signal transduction events. Fibronectin reversed the growth inhibition by mAb 225 for the integrin α5–transfected cells but not the control cells. The reversal of mAb 225–mediated growth inhibition was associated with the activation of EGFR, MEK1, ERK1, and ERK2 and the expression of PCNA. Furthermore, the fibronectin-mediated activation of ERK1 and ERK2 was specific to integrin α5/β1. Direct inhibition of EGFR tyrosine kinase activity by Compound 32 decreased cell proliferation and ERK1 and ERK2 activation. These effects of Compound 32 could not be reversed by fibronectin. These results suggested that EGFR tyrosine kinase activity was necessary for the fibronectin-induced and integrin α5/β1–mediated activation of ERK1 and ERK2 as well as cell proliferation. Furthermore, the inhibition of MAPK activity significantly decreased the proliferation of the control and integrin α5–transfected Caco-2 cells.

Although tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR was seen in both the control and integrin α5–transfected cells cultured on fibronectin, the EGFR coprecipitated with Shc only in the integrin α5 transfectants and in the presence of fibronectin. This suggests that the clustering of integrin α5/β1 receptors by fibronectin resulted in the access of activated EGFR to Shc. Integrins α1/β1 and α5/β1, but not other β1-containing integrin receptors, are coupled to the Ras-ERK pathway through Shc (Wary et al., 1996, 1998). Integrin clustering by fibronectin and integrin α5 antibodies leads to the formation of large signaling complexes containing many substrates of the EGFR, including Grb2 and Shc (Mainiero et al., 1995, 1997; Miyamoto et al., 1995, 1998; Wary et al., 1996, 1998). In addition, integrins can cluster and coprecipitate with EGFRs (Miyamoto et al., 1996; Moro et al., 1998), and we were able to coprecipitate the EGFR with integrin α5 from our integrin α5–transfected cells as well (our unpublished results). Although the activated EGFR can recruit both Grb2 and Shc, the latter appears to be the preferred substrate through which the EGFR activates SOS and then RAS (Sasaoka et al., 1994). Thus, fibronectin not only activates the EGFR but may result in the spatial juxtaposition of Shc with activated EGFRs. This suggests that integrins may play an important spatial regulatory role in controlling interactions between the EGFR and certain substrates. Finally, on fibronectin, ERK1, ERK2, and MEK1 were constitutively activated in the control and integrin α5–transfected cells but were inhibited by mAb 225 only in the control cells. This suggests that the activation of ERK1 and ERK2 may have occurred through somewhat different mechanisms in the two cell types.

Two recent studies that support our results demonstrated activation of the EGFR itself by integrin ligation. In one study, B82L fibroblasts migrated in response to EGF only when the cells were adhered to fibronectin (Li et al., 1999). Furthermore, migration of these cells was dependent on integrin-mediated activation of an intact EGFR in a ligand (growth factor)-independent manner, thus placing the EGFR downstream of integrins for migratory signaling. In another study, when NIH 3T3 cells transfected with the human EGFR were adhered to fibronectin, activation of EGFR, Shc, and ERK1 occurred (Moro et al., 1998). This integrin-mediated activation of the EGFR occurred in the absence of growth factors and was necessary for cell survival and entry into S phase of the cell cycle in the presence of exogenous EGF or serum. Treatment of the cells with the EGFR-specific tyrphostin AG1478 or cotransfection with a dominant-negative mutant EGFR nearly abolished activation of EGFR, Shc, and ERK1 in response to adhesion to fibronectin. This again placed the EGFR downstream of integrins in integrin-mediated ERK1 activation. However, integrin-mediated activation of the EGFR alone was insufficient to drive cell proliferation in the absence of exogenous growth factors, suggesting that integrins potentiated growth factor–mediated activation of ERK1.

A previous study showed that the expression of integrin α5 in the HT-29 colon cell line resulted in growth inhibition in the absence of exogenous fibronectin (Varner et al., 1995). There was no growth arrest in the integrin α5–transfected versus control Caco-2 cell lines in the absence of fibronectin. This may have been due to the fact that Caco-2 cells express endogenous fibronectin and HT-29 cells do not.

The mechanism by which integrin-mediated EGFR activation occurs is currently unknown. It is possible that EGFR activation occurs through a ligand-dependent process such as intracrine EGFR activation (Kennedy et al., 1993; Cao et al., 1995). However, intracrine EGFR activation has been described in only a few cell types, and a growth factor–independent mechanism is more attractive because integrin-mediated EGFR activation occurred in cells devoid of any detectable EGF family growth factor expression (Moro et al., 1998; Li et al., 1999). Another potential mechanism is integrin-induced activation of the EGFR through heterodimerization with another member of the erbB family of receptors (Gamett et al., 1997; Graus-Porta et al., 1997). Caco-2 cells express erbB-2 receptors (our unpublished data), and heterodimerization of the EGFR with erbB-2 could lead to the transactivation of the EGFR even in the absence of EGFR ligand–induced activation (Gamett et al., 1997; Worthylake et al., 1999). In addition, certain colon cancer cells have been reported to express heregulins that stimulate cell proliferation (Vadlamudi et al., 1999). Heregulins can bind to erbB-3 and erbB-4 receptors, which can in turn activate erbB-2, allowing it to heterodimerize with and activate the EGFR. Whether integrins can induce heregulin expression or its binding to erbB3 or erbB4 is unknown. Furthermore, there are no reports yet supporting integrin-stimulated heterodimerization of erbB receptors. Further studies will be necessary to determine whether integrins can cause the activation of erbB-2, thus leading to heterodimerization and activation of the EGFR.

In summary, our results show that the EGFR-RAS-MAPK pathway can be activated downstream of integrin α5/β1 and stimulate epithelial cell proliferation. This adds to a growing body of literature supporting the view that the EGFR-RAS-MAPK pathway can be used as an important signaling pathway by other receptors to control or modulate critical cell functions attributed to EGRF-mediated signaling (Daub et al., 1996; Rosen and Greenberg, 1996; Zwick et al., 1997; Li et al., 1998). Thus, the EGFR appears to play an important role in integrating environmental cues as diverse as cytokines, UV light, and extracellular matrix proteins (Sachsenmaier et al., 1994; Daub et al., 1996, 1997; Moro et al., 1998; Li et al., 1999) to achieve regulation of cell migration, survival, and proliferation. The fine level of integration and orchestration of signaling performed by the EGFR is underscored by the tumorigenic effects caused by the aberrant expression and/or functioning of proteins at all levels of the EGFR-Ras-ERK signal transduction cascade (Gerosa et al., 1989; Ishitoya et al., 1989; Cook et al., 1992; Itakura et al., 1994; Mansour et al., 1994; Rajkumar and Gullick, 1994; Hirono et al., 1995; Normanno et al., 1995; Huang et al., 1996; Stumm et al., 1996; Bucci et al., 1997; Kuttan and Bhakthan, 1997; Sekine et al., 1998).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Dr. H. Steven Wiley for his generous support and technical advice on this project and Dr. Erkki Ruoslahti for providing the human integrin α5 gene. This work was supported by the Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs, and by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases, the Huntsman Cancer Institute, the Glaxo Institute for Digestive Health, and the American Cancer Society.

REFERENCES

- Aliaga JC, Deschenes C, Beaulieu JF, Calvo EL, Rivard N. Requirement of the MAP kinase cascade for cell cycle progression and differentiation of human intestinal cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G631–G641. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.3.G631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ze'ev A, Robinson GS, Bucher NL, Farmer SR. Cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions differentially regulate the expression of hepatic and cytoskeletal genes in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2161–2165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop WP, Lin J, Stein CA, Krieg AM. Interruption of a transforming growth factor alpha autocrine loop in Caco-2 cells by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1882–1889. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop WP, Wen JT. Regulation of Caco-2 cell proliferation by basolateral membrane epidermal growth factor receptors. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:G892–G900. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.5.G892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell DM, Arenson DM, Maher JJ, Roll FJ. Support of cultured hepatocytes by a laminin-rich gel: evidence for a functionally significant subendothelial matrix in normal rat liver. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:801–812. doi: 10.1172/JCI112887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell DM, Guzelian PS. Phenotypic stability of adult rat hepatocytes in primary monolayer culture. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1980;349:85–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb29518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci B, D'Agnano I, Botti C, Mottolese M, Carico E, Zupi G, Vecchione A. EGF-R expression in ductal breast cancer: proliferation and prognostic implications. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:769–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Lei ZM, Bian L, Rao CV. Functional nuclear epidermal growth factor receptors in human choriocarcinoma JEG-3 cells and normal human placenta. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3163–3172. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.7.7540549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Kinch MS, Lin TH, Burridge K, Juliano RL. Integrin-mediated cell adhesion activates mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26602–26605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark EA, Brugge JS. Integrins and signal transduction pathways: the road taken. Science. 1995;268:233–239. doi: 10.1126/science.7716514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PW, Pittelkow MR, Keeble WW, Graves Deal R, Coffey RJ, Jr, Shipley GD. Amphiregulin messenger RNA is elevated in psoriatic epidermis and gastrointestinal carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3224–3227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley S, Paterson H, Kemp P, Marshall CJ. Activation of MAP kinase kinase is necessary and sufficient for PC12 differentiation and for transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Cell. 1994;77:841–852. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damstrup L, Kuwada SK, Dempsey PJ, Brown CL, Hawkey CJ, Poulsen HS, Wiley HS, Coffey RJ., Jr Amphiregulin acts as an autocrine growth factor in two human polarizing colon cancer lines that exhibit domain selective EGF receptor mitogenesis. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1012–1019. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daub H, Wallasch C, Lankenau A, Herrlich A, Ullrich A. Signal characteristics of G protein-transactivated EGF receptor. EMBO J. 1997;16:7032–7044. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daub H, Weiss FU, Wallasch C, Ullrich A. Role of transactivation of the EGF receptor in signaling by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 1996;379:557–560. doi: 10.1038/379557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriola PC, Earp HS, Di Augustine R, Nettesheim P. Role of TGF alpha and its receptor in proliferation of immortalized rat tracheal epithelial cells: studies with tyrphostin and TGF alpha antisera. J Cell Physiol. 1991;147:166–175. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041470121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriola PC, Robertson AT, Rusnak DW, Diaugustine R, Nettesheim P. Epidermal growth factor dependence and TGF alpha autocrine growth regulation in primary rat tracheal epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1992;152:302–309. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041520211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J, Moscona A. Role of cell shape in growth control. Nature. 1978;273:345–349. doi: 10.1038/273345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamett DC, Pearson G, Cerione RA, Friedberg I. Secondary dimerization between members of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12052–12056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AJ, Vega MD, Boettiger D. Modulation of cell proliferation and differentiation through substrate-dependent changes in fibronectin conformation. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:785–798. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.3.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerosa MA, Talarico D, Fognani C, Raimondi E, Colombatti M, Tridente G, De Carli L, Della Valle G. Overexpression of N-ras oncogene and epidermal growth factor receptor gene in human glioblastomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:63–67. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti FG. Integrin signaling: specificity and control of cell survival and cell cycle progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:691–700. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill GN, Kawamoto T, Cochet C, Le A, Sato JD, Masui H, McLeod C, Mendelsohn J. Monoclonal anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies which are inhibitors of epidermal growth factor binding and antagonists of epidermal growth factor binding and antagonists of epidermal growth factor-stimulated tyrosine protein kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:7755–7760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graus-Porta D, Beerli RR, Daly JM, Hynes NE. ErbB-2, the preferred heterodimerization partner of all ErbB receptors, is a mediator of lateral signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16:1647–1655. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks SK, Polte TR. Signaling through focal adhesion kinase. Bioessays. 1997;19:137–145. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler ME. VLA proteins in the integrin family: structures, functions, and their role on leukocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:365–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo IJ, Kato A, Borchardt RT. Binding of epidermal growth factor by human colon carcinoma cell (Caco-2) monolayers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989a;160:317–324. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91658-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo IJ, Raub TJ, Borchardt RT. Characterization of the human colon carcinoma cell line (Caco-2) as a model system for intestinal epithelial permeability. Gastroenterology. 1989b;96:736–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirono Y, Tsugawa K, Fushida S, Ninomiya I, Yonemura Y, Miyazaki I, Endou Y, Tanaka M, Sasaki T. Amplification of epidermal growth factor receptor gene and its relationship to survival in human gastric cancer. Oncology. 1995;52:182–188. doi: 10.1159/000227455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TS, Rauth S, Das Gupta TK. Overexpression of EGF receptor is associated with spontaneous metastases of a human melanoma cell line in nude mice. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:3557–3563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE. Fibronectin controls capillary endothelial cell growth by modulating cell shape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3579–3583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitoya J, Toriyama M, Oguchi N, Kitamura K, Ohshima M, Asano K, Yamamoto T. Gene amplification and overexpression of EGF receptor in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:559–562. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura Y, Sasano H, Shiga C, Furukawa Y, Shiga K, Mori S, Nagura H. Epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression in esophageal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study correlated with clinicopathologic findings and DNA amplification. Cancer. 1994;74:795–804. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940801)74:3<795::aid-cncr2820740303>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher MD, Abe MK, Chao TS, Jain M, Green JM, Solway J, Rosner MR, Hershenson MB. Role of MAP kinase activation in bovine tracheal smooth muscle mitogenesis. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L894–L901. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.6.L894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy TG, Brown KD, Vaughan TJ. Expression of the genes for the epidermal growth factor receptor and its ligands in porcine corpora lutea. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1857–1859. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.4.8462481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuttan NA, Bhakthan NM. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in oral squamous cell carcinomas: overexpression, localization and therapeutic implications. Indian J Dent Res. 1997;8:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwada SK, Li XF, Damstrup L, Dempsey PJ, Coffey RJ, Wiley HS. The dynamic expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and epidermal growth factor ligand family in a differentiating intestinal epithelial cell line. Growth Factors. 1999;17:139–153. doi: 10.3109/08977199909103522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Carter CA, Johnson GL. Ras-dependent growth factor regulation of MEK kinase in PC12 cells. Science. 1994;265:1458–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.8073291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy P, Loreal O, Munier A, Yamada Y, Picard J, Cherqui G, Clement B, Capeau J. Enterocytic differentiation of the human Caco-2 cell line is correlated with down-regulation of fibronectin and laminin. FEBS Lett. 1994;338:272–276. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Lin ML, Wiepz GJ, Guadarrama AG, Bertics PJ. Integrin-mediated migration of murine B82L fibroblasts is dependent on the expression of an intact epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11209–11219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Lee JW, Graves LM, Earp HS. Angiotensin II stimulates ERK via two pathways in epithelial cells: protein kinase C suppresses a G-protein coupled receptor-EGF receptor transactivation pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:2574–2583. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainiero F, Murgia C, Wary KK, Curatola AM, Pepe A, Blumemberg M, Westwick JK, Der CJ, Giancotti FG. The coupling of alpha6beta4 integrin to Ras-MAP kinase pathways mediated by Shc controls keratinocyte proliferation. EMBO J. 1997;16:2365–2375. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainiero F, Pepe A, Wary KK, Spinardi L, Mohammadi M, Schlessinger J, Giancotti FG. Signal transduction by the alpha 6 beta 4 integrin: distinct beta 4 subunit sites mediate recruitment of Shc/Grb2 and association with the cytoskeleton of hemidesmosomes. EMBO J. 1995;14:4470–4481. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour SJ, Matten WT, Hermann AS, Candia JM, Rong S, Fukasawa K, Vande Woude GF, Ahn NG. Transformation of mammalian cells by constitutively active MAP kinase kinase. Science. 1994;265:966–970. doi: 10.1126/science.8052857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Katz BZ, Lafrenie RM, Yamada KM. Fibronectin and integrins in cell adhesion, signaling, and morphogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;857:119–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Teramoto H, Coso OA, Gutkind JS, Burbelo PD, Akiyama SK, Yamada KM. Integrin function: molecular hierarchies of cytoskeletal and signaling molecules. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:791–805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Teramoto H, Gutkind JS, Yamada KM. Integrins can collaborate with growth factors for phosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases and MAP kinase activation: roles of integrin aggregation and occupancy of receptors. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1633–1642. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morino N, Mimura T, Hamasaki K, Tobe K, Ueki K, Kikuchi K, Takehara K, Kadowaki T, Yazaki Y, Nojima Y. Matrix/integrin interaction activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase, p44erk-1 and p42erk-2. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:269–273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro L, Venturino M, Bozzo C, Silengo L, Altruda F, Beguinot L, Tarone G, Defilippi P. Integrins induce activation of EGF receptor: role in MAP kinase induction and adhesion-dependent cell survival. EMBO J. 1998;17:6622–6632. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normanno N, Selvam MP, Bianco C, Damiano V, de Angelis E, Grassi M, Magliulo G, Tortora G, Salomon DS, Ciardiello F. Amphiregulin anti-sense oligodeoxynucleotides inhibit growth and transformation of a human colon carcinoma cell line. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:762–766. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages G, Lenormand P, L'Allemain G, Chambard JC, Meloche S, Pouyssegur J. Mitogen-activated protein kinases p42mapk and p44mapk are required for fibroblast proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8319–8323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelicci G, Lanfrancone L, Grignani F, McGlade J, Cavallo F, Forni G, Nicoletti I, Pawson T, Pelicci PG. A novel transforming protein (SHC) with an SH2 domain is implicated in mitogenic signal transduction. Cell. 1992;70:93–104. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90536-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignatelli M, Bodmer WF. Integrin-receptor-mediated differentiation and growth inhibition are enhanced by transforming growth factor-beta in colorectal tumor cells grown in collagen gel. Int J Cancer. 1989;44:518–523. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910440324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar T, Gullick WJ. The type I growth factor receptors in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;29:3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00666177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LB, Greenberg ME. Stimulation of growth factor receptor signal transduction by activation of voltage-sensitive calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1113–1118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskelley CD, Desprez PY, Bissell MJ. Extracellular matrix-dependent tissue-specific gene expression in mammary epithelial cells requires both physical and biochemical signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12378–12382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozakis-Adcock M, Fernley R, Wade J, Pawson T, Bowtell D. The SH2 and SH3 domains of mammalian Grb2 couple the EGF receptor to the Ras activator mSos1. Nature. 1993;363:83–85. doi: 10.1038/363083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff-Jamison S, McGlade J, Pawson T, Chen K, Cohen S. Epidermal growth factor stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of SHC in the mouse. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:7610–7612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachsenmaier C, Radler-Pohl A, Zinck R, Nordheim A, Herrlich P, Rahmsdorf HJ. Involvement of growth factor receptors in the mammalian UVC response. Cell. 1994;78:963–972. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaoka T, Langlois WJ, Leitner JW, Draznin B, Olefsky JM. The signaling pathway coupling epidermal growth factor receptors to activation of p21ras. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32621–32625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry SK, Lakonishok M, Thomas DA, Muschler J, Horwitz AF. Integrin alpha subunit ratios, cytoplasmic domains, and growth factor synergy regulate muscle proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:169–184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer DD, Hanks SK, Hunter T, van der Geer P. Integrin-mediated signal transduction linked to Ras pathway by GRB2 binding to focal adhesion kinase. Nature. 1994;372:786–791. doi: 10.1038/372786a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer DD, Jones KC, Hunter T. Multiple Grb2-mediated integrin-stimulated signaling pathways to ERK2/mitogen-activated protein kinase: summation of both c-Src- and focal adhesion kinase-initiated tyrosine phosphorylation events. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2571–2585. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MA, Baron V. Interactions between mitogenic stimuli, or, a thousand and one connections. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine I, Takami S, Guang SG, Yokose T, Kodama T, Nishiwaki Y, Kinoshita M, Matsumoto H, Ogura T, Nagai K. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression, K-ras point mutation and c-myc amplification in the carcinogenesis of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 1998;5:351–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Assmann P, Kedinger M, Haffen K. Immunocytochemical localization of extracellular-matrix proteins in relation to rat intestinal morphogenesis. Differentiation. 1986;32:59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1986.tb00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somasiri A, Roskelley CD. Cell shape and integrin signaling regulate the differentiation state of mammary epithelial cells. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;129:271–283. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-249-X:271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streuli CH, Bailey N, Bissell MJ. Control of mammary epithelial differentiation: basement membrane induces tissue-specific gene expression in the absence of cell-cell interaction and morphological polarity. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1383–1395. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumm G, Eberwein S, Rostock-Wolf S, Stein H, Pomer S, Schlegel J, Waldherr R. Concomitant overexpression of the EGFR and erbB-2 genes in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is correlated with dedifferentiation and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 1996;69:17–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960220)69:1<17::AID-IJC4>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong WM, Ellinger A, Sheinin Y, Cross HS. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression in primary cultured human colorectal carcinoma cells. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1792–1798. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachon PH, Simoneau A, Herring Gillam FE, Beaulieu JF. Cellular fibronectin expression is down-regulated at the mRNA level in differentiating human intestinal epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 1995;216:30–34. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi R, Mandal M, Adam L, Steinbach G, Mendelsohn J, Kumar R. Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 pathway by HER2 receptor. Oncogene. 1999;18:305–314. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varner JA, Emerson DA, Juliano RL. Integrin alpha 5 beta 1 expression negatively regulates cell growth: reversal by attachment to fibronectin. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:725–740. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.6.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Sun L, Zborowska E, Willson JK, Gong J, Verraraghavan J, Brattain MG. Control of type II transforming growth factor-beta receptor expression by integrin ligation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12840–12847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wary KK, Mainiero F, Isakoff SJ, Marcantonio EE, Giancotti FG. The adaptor protein Shc couples a class of integrins to the control of cell cycle progression. Cell. 1996;87:733–743. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wary KK, Mariotti A, Zurzolo C, Giancotti FG. A requirement for caveolin-1 and associated kinase Fyn in integrin signaling and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Cell. 1998;94:625–634. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley HS, Cunningham DD. A steady state model for analyzing the cellular binding, internalization and degradation of polypeptide ligands. Cell. 1981;25:433–440. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthylake R, Opresko LK, Wiley HS. ErbB-2 amplification inhibits down-regulation and induces constitutive activation of both ErbB-2 and epidermal growth factor receptors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8865–8874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Assoian RK. Integrin-dependent activation of MAP kinase: a link to shape-dependent cell proliferation. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:273–282. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.3.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Assoian RK. Integrin-dependent activation of MAP kinase: a link to shape-dependent cell proliferation. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7,:1001. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.3.273. (Errata). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwick E, Daub H, Aoki N, Yamaguchi-Aoki Y, Tinhofer I, Maly K, Ullrich A. Critical role of calcium-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation in PC12 cell membrane depolarization and bradykinin signaling. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24767–24770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]