Abstract

It is widely thought that the biological outcomes of Raf-1 activation are solely attributable to the activation of the MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway. However, an increasing number of reports suggest that some Raf-1 functions are independent of this pathway. In this report we show that mutation of the amino-terminal 14-3-3 binding site of Raf-1 uncouples its ability to activate the MEK/ERK pathway from the induction of cell transformation and differentiation. In NIH 3T3 fibroblasts and COS-1 cells, mutation of serine 259 resulted in Raf-1 proteins which activated the MEK/ERK pathway as efficiently as v-Raf. However, in contrast to v-Raf, RafS259 mutants failed to transform. They induced morphological alterations and slightly accelerated proliferation in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts but were not tumorigenic in mice and behaved like wild-type Raf-1 in transformation assays measuring loss of contact inhibition or anchorage-independent growth. Curiously, the RafS259 mutants inhibited focus induction by an activated MEK allele, suggesting that they can hyperactivate negative-feedback pathways. In primary cultures of postmitotic chicken neuroretina cells, RafS259A was able to sustain proliferation to a level comparable to that sustained by the membrane-targeted transforming Raf-1 protein, RafCAAX. In contrast, RafS259A was only a poor inducer of neurite formation in PC12 cells in comparison to RafCAAX. Thus, RafS259 mutants genetically separate MEK/ERK activation from the ability of Raf-1 to induce transformation and differentiation. The results further suggest that RafS259 mutants inhibit signaling pathways required to promote these biological processes.

The Raf family of serine/threonine kinases lie at the apex of a highly conserved protein kinase module which relays extracellular signals to the nucleus. The best-studied member of the family, Raf-1, was originally isolated as the cellular homologue of the v-Raf oncogene (5). Oncogenic forms of Raf-1 can be created by deletion of the regulatory domain (12, 41) or by membrane targeting (21, 42). In v-Raf, the regulatory domain is replaced by retroviral Gag sequences, and several oncogenic Raf-1 variants where the regulatory domain is either removed or replaced have been isolated (reviewed in reference 43). This form of activation is thought to release the kinase domain from the inhibitory constraints imposed by the regulatory domain. In resting cells Raf-1 is cytosolic and is held in an inactive state by a 14-3-3 dimer bound to phosphoserines 259 and 621 (reviewed in reference 17). In a recently proposed model, upon translocation of Raf-1 to the membrane, the interaction of Raf-1 with Ras-GTP displaces 14-3-3 from serine 259, making it accessible to dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 2A (7). This releases the kinase domain from the inhibitory influence of the regulatory domain and enhances the subsequent phosphorylation of the kinase domain by activating kinases. Artificially anchoring Raf-1 to the membrane via a CAAX box mimics the translocation step, resulting in an activated Raf-1 protein that can transform cells. However, RafCAAX is still responsive to activation by mitogens and Ras (21, 28, 38). Activated Raf-1 phosphorylates and activates MEK, which in turn phosphorylates and activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Thus, Raf-1 connects the Ras proto-oncogene to the ubiquitous ERK pathway, which regulates fundamental cellular processes including proliferation, transformation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Importantly, with regard to transformation and differentiation, Raf appears to be the main effector of Ras (6).

The Raf-MEK/ERK cascade has been perceived as a linear signaling pathway with ERK at the effector end. This view stems from several observations. First, in contrast to most other kinases, Raf and MEK have extremely narrow substrate specificities in vivo and in vitro. The only known MEK substrates are ERK1 and ERK2 (reviewed in reference 39). Likewise, MEK remains the only commonly accepted bona fide Raf-1 substrate, although work with different systems has indicated that Raf-1 may have other effectors in addition to the MEK/ERK pathway (15, 20, 22, 27, 33, 48, 49). Kinase-negative MEK mutants and chemical MEK inhibitors block fibroblast transformation and PC12 cell differentiation induced by oncogenic Ras or Raf (6, 9), whereas activated MEK alleles promote these phenomena (6). The key events required for these oncogenes to induce both fibroblast transformation and PC12 cell differentiation appear to be the sustained activation of ERK and its translocation to the nucleus (25). While these experiments demonstrate that the MEK/ERK pathway is a major arm of Raf-1 signaling, they do rule out the existence of additional Raf-1 effectors. The evidence for this is increasing. For instance, Raf-driven differentiation of hippocampal neurons (20) and the prevention of apoptosis (15, 23, 27, 47, 49) appear to be MEK independent. Several recent studies have indicated that serine 259 plays a important role in the regulation of Raf-1 signaling (7, 8, 10, 19, 54). Here we have studied the biological consequences of mutating serine 259 with respect to transformation, proliferation, and differentiation. We show that RafS259 mutants activate the MEK/ERK pathway with an efficiency similar to that of oncogenic Raf proteins but fail to transform and only poorly induce differentiation. However, they retain the capacity to stimulate proliferation. Thus, this mutation genetically dissociates the ability of Raf-1 to activate the MEK/ERK pathway from transformation and differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression vectors and reagents.

Raf serine 259 was changed to alanine or aspartic acid by site-directed mutagenesis and cloned into pCMV5 (2) and ELneo (13) for transient and stable expression, respectively. BXB is a Raf-1 deletion mutant where amino acids 26 to 303 were removed (13). RafΔN is a deletion mutant cloned into Elneo where the entire regulatory domain was deleted and is identical to the previously described EC12 (13). v-Raf was expressed from the 3611 murine sarcoma virus plasmid clone (35). Expression vectors for hemagglutinin (HA)-RasV12, HA-MEK, and HA-ERK were from Michael White, Michael Weber, and Michael Karin, respectively. pcDNA3-FLAG Raf-1 WT and FLAG RafCAAX were kindly provided by Debbie Morrison.

For immunoprecipitation and Western blotting of Raf proteins, an antiserum against the 12 C-terminal amino acids of Raf-1 was raised in rabbits (11). Antibodies against RKIP were made as described previously (52). The phospho-MEK and IκBα antibodies were purchased from New England Biolabs, phospho-ERK was from Sigma, cyclin D was from Neomarkers, and the HA tag antibodies were from LaRoche Diagnostics.

Cell culture and transfection.

NIH 3T3 and COS-1 cells were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). COS-1 cells were transfected in six-well plates with 1.5 μg each of DNA per well by using DEAE-dextran-chloroquine as described previously (28). NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with 1 μg of DNA per well of a six-well plate by using calcium phosphate, Lipofectin (Gibco), or Effectene (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PC12 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS and 10% horse serum on rat tail collagen-coated dishes. Cells were cotransfected with 3.0 μg of pcDNA3-derived constructs and 0.2 μg of pEGFP-C3 reporter construct, encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (Clontech) by using Lipofectamin 2000 reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Images were captured on an inverted microscope (Leica; DM IRB) with a 12-bit MicroMax camera (Ropper Scientific) and the MetaView software (Universal Imaging). Neuroretina (NR) cells were dissected and seeded in a 6-cm-diameter petri dish as previously described (32). Cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate method as previously described (32) by using 10 μg of plasmid DNA per dish, and G418 selection (600 μg/ml) was applied 5 days later, for 15 days. Foci of proliferating cells were stained with 1.0% crystal violet (in 20% ethanol).

Transformation assays.

For focus assays, NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with Raf expression vectors in six-well plates. Elneo-based plasmids, which express the G418 resistance gene, were used for most experiments. When pCMV5-based vectors were used, they were cotransfected with the empty Elneo vector at a ratio of 5:1, yielding comparable results. Cells were split 3 days posttransfection, with one-fourth selected with 0.5 mg of G418/ml to determine the number of transfected clones. The remaining cells were allowed to grow to confluence and examined for focus formation. The growth medium was replaced every 3 days. Foci and colonies were counted, and focus formation was expressed as the percentage of foci per transfected cell clone. G418-resistant clones were randomly picked by ring cloning and expanded into cell lines. In the experiments shown in Fig. 9, cells were transfected in triplicate. One set was harvested 3 days posttransfection and used to assess if the transfected cDNAs were successfully expressed. The two remaining sets were used for focus assays. Foci were visualized 2 weeks posttransfection by Giemsa staining.

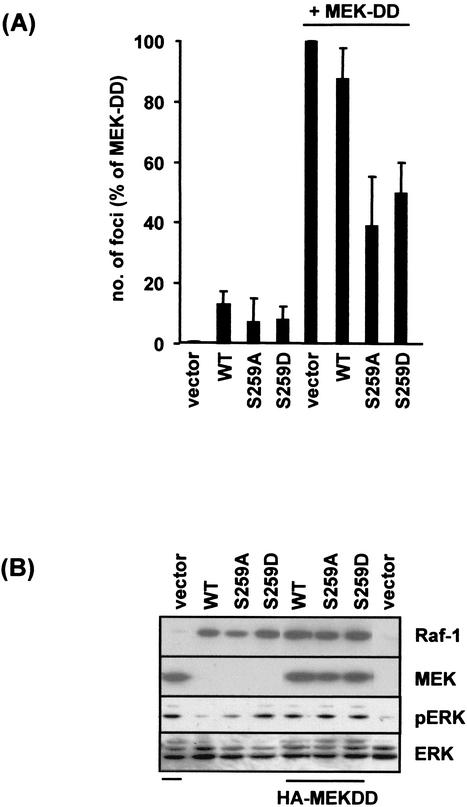

FIG. 9.

RafS259 mutants inhibit focus induction by MEK-DD. (A) NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with the indicated expression constructs and focus assays were performed as described in the Materials and Methods. The data show the percentages of focus formation relative to that for cells transfected with MEK-DD alone and represent the means ± standard errors of the means for three independent experiments. (B) Expression of Raf-1 and MEK constructs in whole-cell lysates from transfected cells used in the focus assays. Cells were lysed 2 days after transfection and blotted with the indicated antibodies. WT, wild type.

For growth curves 10,000 cells were seeded in 12-well plates. At each time point duplicate wells were trypsinized and the cells were counted in a Coulter counter. The growth medium was not replenished during the duration of the experiment. For soft-agar assays 100,000 cells were resuspended in 1 ml of top agar (DMEM plus 10% FCS containing 0.4% Noble agar; Difco) warmed to 40°C. The cell suspension was layered onto 3 ml of set bottom agar (DMEM plus 10% FCS containing 0.5% Noble agar) in a six-well plate. The plates were fed once a week by overlaying the agar with 1 ml of fresh medium. SCID mice were inoculated subcutaneously with pools of NIH 3T3 cells (2 × 106 per injection) transfected with Elneo-based expression vectors for Raf-1, RafS259D, and v-Raf. Vector control cells were injected into the opposite flank. Equal numbers of cells were injected, and Western blotting with anti-Raf-1 antibodies was used to ensure that equal levels of the proteins were expressed. Tumor growth was scored 4 weeks after inoculation, when the animals were killed because of the tumor burden, in compliance with animal welfare regulations.

Kinase assays and reporter gene assays.

Raf activity was measured as described previously (29) by a linked assay, where Raf immunoprecipitates were incubated with recombinant MEK-1 and kinase-dead ERK-2 proteins. This assay measures the ability of Raf to phosphorylate and activate MEK. MEK activation was detected by measuring the phosphorylation of kinase-negative ERK. Reporter gene assays were performed as described previously (18) with pF711CAT, which contains the c-fos promoter from −711 to +42 fused to the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene.

Immunofluorescence.

For immunofluorescence detection of activated ERK, cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, permeabilized in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-1% bovine serum albumin-0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min, and then blocked in TBS-10% FCS for 30 min at room temperature. After each of the above steps, cells were washed three times with TBS. The cells were incubated with a 1/100 dilution of the anti-phospho-ERK antibody (Sigma) overnight at 4°C, then at room temperature for 1 h with a biotinylated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (1/750; Vector labs), and finally within streptavidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (1/100) for a further hour. Between each incubation with antibodies, the cells were washed four times with TBS-0.025% Tween 80. The cells were then mounted in Vectastain (Molecular Probes).

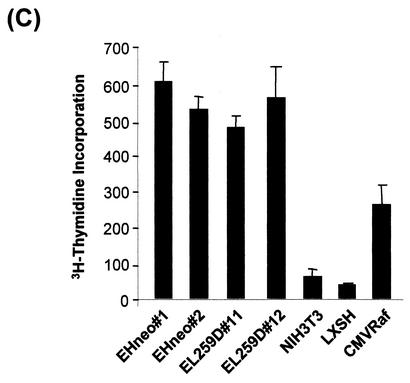

[3H]thymidine uptake.

Ten thousand cells were seeded in triplicate in 96-well plates and grown in medium containing 1% FCS for 72 h. [3H]thymidine (0.2 μCi) was added to two of the wells for 6 h before the cells were washed, trypsinized, lysed in water, and spotted onto Whatman 3MM filter paper. After a washing, the papers were placed in a scintillation counter. The third well was assayed for protein content and used to normalize the level of [3H]thymidine incorporation. Similar results were obtained when the cells were grown in low-serum-containing medium for 24 h before addition of [3H]thymidine.

RESULTS

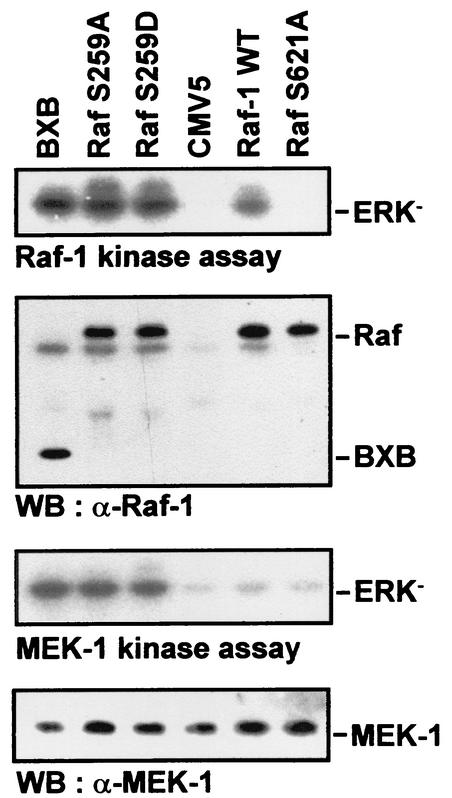

Raf-1 serine 259 mutants constitutively activate the MEK/ERK pathway.

The mutation of serine 259 in Raf-1 has previously been shown to elevate its kinase activity (7, 30, 36, 54). To test if this enhanced activity correlated with an increase in Raf's ability to activate the substrate MEK, COS-1 cells were cotransfected with HA-MEK together with RafS259A or RafS259D mutants (Fig. 1). For comparison, an activated Raf-1 mutant lacking the regulatory domain (termed BXB) and a kinase-dead Raf-1 mutant (S621A) were used. The amount of transfected Raf plasmid DNA was adjusted to yield equal protein expression. The RafS259 mutants displayed enhanced kinase activities, comparable to that of BXB. Both mutants behaved equivalently in this assay as well as in all other assays performed. The activity of wild-type Raf-1 was less than that of the S259 mutants but clearly higher than that of the vector and RafS621A controls. When the activity of the cotransfected HA-MEK was examined, it was found that wild-type Raf-1 activated MEK to the same level as the controls. In contrast, the RafS259 mutants and BXB induced a robust activation of HA-MEK with very similar efficiencies. These results show that the RafS259 mutants and the oncogenic Raf-1 mutant BXB can activate the MEK/ERK pathway to similar extents.

FIG. 1.

Mutation of Raf-1 serine 259 increases MEK activation in COS-1 cells. COS-1 cells were cotransfected with HA-MEK-1 and the indicated pCMV5-based expression vectors. Raf-1S621A lacks detectable kinase activity (29) and was used as a control. Raf immunoprecipitates were tested for their ability to activate MEK by incubation with recombinant MEK-1 and kinase-dead ERK (ERK−). HA-MEK-1 was immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA antibody and assayed for its ability to phosphorylate ERK−. The kinase reactions were blotted. The blots were autoradiographed and stained with antibodies to Raf-1 and MEK.

Mutation of serine 259 does not render Raf-1 tumorigenic.

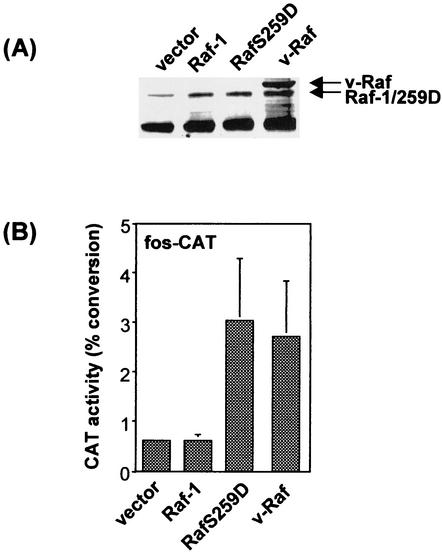

The MEK/ERK pathway is considered to be the main effector arm of Raf-1 in cell transformation (6). Since BXB and v-Raf are oncogenic, we anticipated that the RafS259 mutants would also be oncogenic. However, when we tested the RafS259D mutant for tumorigenicity in immunocompromised SCID mice, we were surprised to find that RafS259D cells failed to form tumors (Table 1). By contrast, four out of five mice injected with v-Raf-transfected cells developed tumors. As assessed by Western blotting, the overexpression of RafS259D in the injected cells was equal to that of Raf-1 and slightly less than that of v-Raf (Fig. 2A). Therefore, we tested for the functionality of the whole pathway by measuring the transcriptional activity of an ERK-dependent fos-CAT reporter gene (18) (Fig. 2B). In this functional assay v-Raf and RafS259D behaved very similarly, suggesting that the failure of RafS259D to induce tumors is not simply a consequence of poorer activation of ERK and downstream targets. To determine the basis for this unexpected lack of tumorigenicity of the RafS259D mutant, we decided to further characterize the RafS259 mutants with regard to activation of the MEK/ERK pathway in several in vitro transformation assays that measure different characteristics of the transformed phenotype.

TABLE 1.

Tumorigenicity of RafS259D cells in SCID micea

| Transfectant | No. of mice:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| With tumors | Inoculated | |

| Vectorb | 0 | 5 |

| Raf-1 | 0 | 5 |

| RafS259D | 0 | 5 |

| v-Raf | 4 | 5 |

NIH 3T3 cells transfected with Raf-1, RafS259D, or v-Raf were injected subcutaneously into SCID mice. Tumor growth was scored 4 weeks after inoculation when the experiment was terminated.

All mice were inoculated with vector control cells into the opposite flank.

FIG. 2.

Raf protein expression (A) and activation of a fos-CAT reporter in NIH 3T3 cells used for inoculation into SCID mice (B). NIH 3T3 cell lysates were blotted and stained with an antibody against the 12 C terminus amino acids of Raf-1.

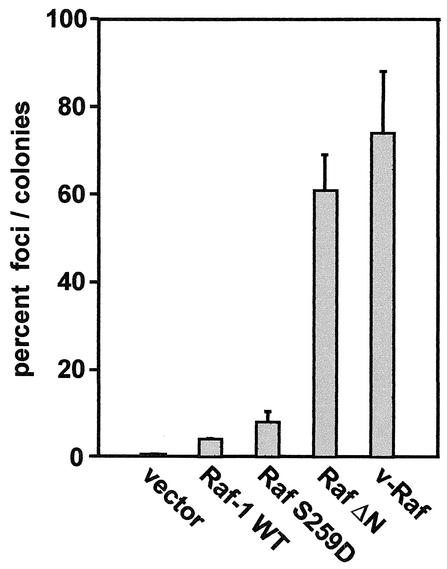

RafS259D cells retain contact inhibition.

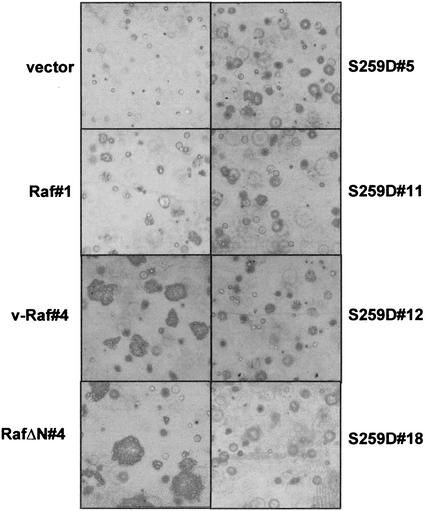

To test for loss of contact inhibition, focus assays were performed with NIH 3T3 cells. To correct the number of foci counted for differences in transfection efficiencies, expression plasmids containing a G418 resistance gene were used for selection. In cells transfected with RafΔN or v-Raf, more than 60% of transfected cells formed foci, whereas less than 10% of RafS259D-transfected cells did (Fig. 3). This was only twofold more than the percentage of cells transfected with wild-type Raf-1, indicating that RafS259D cells preserved a high degree of contact inhibition. Foci induced by Raf-1 and RafS259D were small and in most cases could be seen only through the microscope. By contrast, RafΔN and v-Raf foci proliferated vigorously and were readily visible to the naked eye. We also made clonal cell lines which were used in the experiments described below by randomly picking and expanding G418-resistant colonies. Such cell lines were established from three different experiments, and on two occasions cell lines were also established from the foci. There were no significant differences between the cell lines established from different experiments, and the data presented below serve as representative examples.

FIG. 3.

Reduced ability of RafS259D to form foci. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with Raf expression plasmids and examined for focus formation. Foci were counted 2 weeks posttransfection. To account for differences in transfection efficiencies, an aliquot of transfected cells was selected with G418 and resistant colonies were counted. The data are represented as the percentages of foci per G418-resistant colony and are representative of three independent experiments.

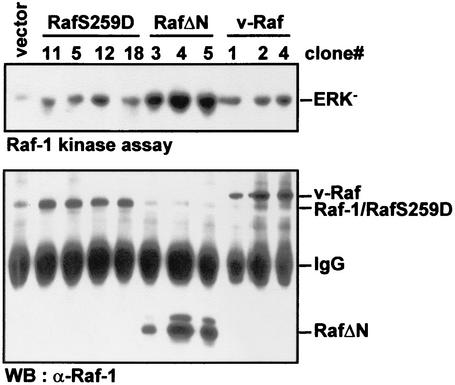

RafS259 and v-Raf possess similar kinase activities in stably transfected NIH 3T3 cells.

The cell lines were analyzed for Raf protein expression and Raf kinase activity (Fig. 4) as well as for the expression and activation of MEK (Fig. 5A). RafΔN cell clones featured the highest Raf expression and kinase activities. However, despite variable levels of RafΔN protein expression, their kinase activities were remarkably similar. Since hyperactivation of Raf-1 above a certain threshold induces cell cycle arrest rather than proliferation (34, 40, 50), the kinase activity in the RafΔN cells probably reflects the maximum Raf activity that is compatible with cell proliferation. The v-Raf clones showed less variation in v-Raf expression levels but had clearly elevated Raf kinase activities. However, the kinase activities were lower than those in RafΔN cells. Cells expressing RafS259D (or RafS259A; data not shown) had Raf kinase activities and protein expression levels comparable to those of v-Raf-transfected cells. Fully consistent data were obtained in cell pools from transient transfections (data not shown), where the relative Raf kinase activities also were RafΔN > v-Raf ≈ RafS259 > Raf-1 = vector.

FIG. 4.

Raf protein expression in selected NIH 3T3 cell clones. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with the Raf expression vectors indicated and selected with G418. Randomly picked clones were expanded and immunoblotted for Raf protein expression and assayed for Raf kinase activity as described for Fig. 1. WB, Western blot; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

FIG. 5.

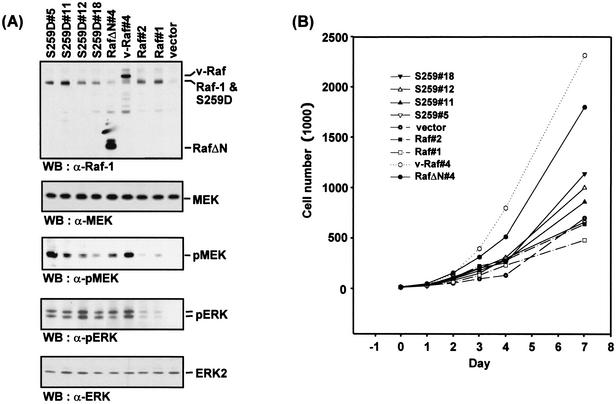

(A) Western blot (WB) analysis of Raf and MEK protein expression in randomly picked G418-selected NIH 3T3 cell clones. The levels of activated MEK (pMEK) were determined with a phospho-specific antibody. (B) RafS259D expression accelerates cell proliferation. Growth curves of the clones shown in panel A. Data represent the averages of three independent experiments, where duplicate samples were counted for each time point. (C) [3H]thymidine uptake by NIH 3T3 clones cultured in low-serum (1% FCS)-containing medium.

RafS259D enhances MEK activation and slightly increases the proliferation rate of NIH 3T3 cells.

For examination of MEK activation and proliferation rate in the cell lines, biochemical analysis was performed at the same time as the growth curves in order to assess any changes in Raf protein expression that had occurred during passaging in culture. Since Raf-1 expression tended to be downregulated during prolonged cultivation, fresh low-passage-number cells were used and Raf protein expression was monitored in each experiment. MEK activation was measured by using a phospho-specific antibody, which selectively recognizes activated MEK (Fig. 5A). The level of activated MEK in RafS259 clones was highly variable and showed only a poor correlation with RafS259 expression levels. This was also observed when more clones were analyzed (data not shown). The reason for this is unknown, but it is reminiscent of the results of a previous study, which noted that in cells transformed with activated MEK mutants there was no correlation between the degree of transformation and ERK activity (1). Importantly, however, the ranges of MEK and ERK activities in RafS259 clones were comparable to those seen in RafΔN and v-Raf lines. There was also no correlation between MEK activities and ERK activities in these cells. Growth curves showed that Raf-1 overexpression did not confer a proliferative advantage versus vector control cells (Fig. 5B). In contrast, RafΔN and v-Raf cells proliferated much faster. RafS259D enhanced cell proliferation to intermediate levels. However, there was no correlation with the level of RafS259D overexpression. These results indicate that a simple causal relationship between MEK activity and proliferation is unlikely. In addition, [3H]thymidine uptake assays showed that v-Raf and RafS259D cells retained the ability to proliferate under a low-serum condition, indicating that these cells had overcome the requirement for serum to proliferate (Fig. 5C).

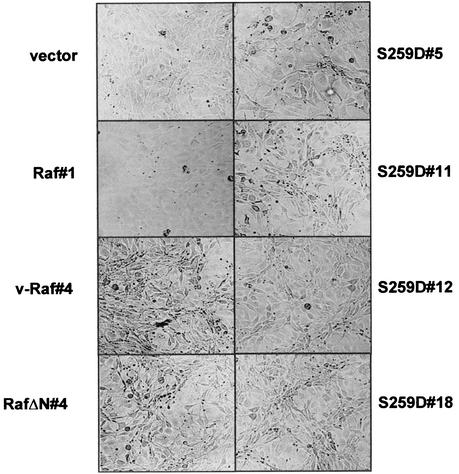

Effects of RafS259D mutants on cell morphology and anchorage-independent growth.

Raf S259D clones displayed some of the morphological changes associated with fibroblast transformation, i.e., elongated shape, rounding, and irregular growth pattern. These changes made them easily distinguishable from the flat vector control and Raf-1 cells, although they were much less pronounced than the highly transformed phenotypes of v-Raf and RafΔN clones (Fig. 6 and data not shown). Again, the extent of the changes did not correlate with the levels of RafS259D protein expression or MEK activity. Although the growth pattern was disordered, contact inhibition was largely retained. This is consistent with the failure to efficiently form foci.

FIG. 6.

Morphology of RafS259D cells. The NIH 3T3-derived cell clones used in Fig. 5 were photographed at ×100 magnification with a Zeiss Axiovert microscope.

To test for anchorage dependence, cell lines were seeded in soft agar (Fig. 7). v-Raf and RafΔN transfectants readily formed colonies, which became macroscopically visible within 14 days and which further increased in size upon prolonged incubation. In contrast, RafS259D and wild-type Raf-1 clones formed small colonies that were not detectable with the naked eye. These colonies did not progress, even when incubated for up to 3 weeks. In the fibroblast system this assay is a rather accurate predictor of tumorigenicity, and the failure of RafS259D cells to support anchorage-independent growth is in keeping with their failure to form tumors in SCID mice.

FIG. 7.

Anchorage-independent growth of RafS259D cells. The cell clones used in Fig. 6 were seeded into soft agar. Colonies were photographed 2 weeks after seeding.

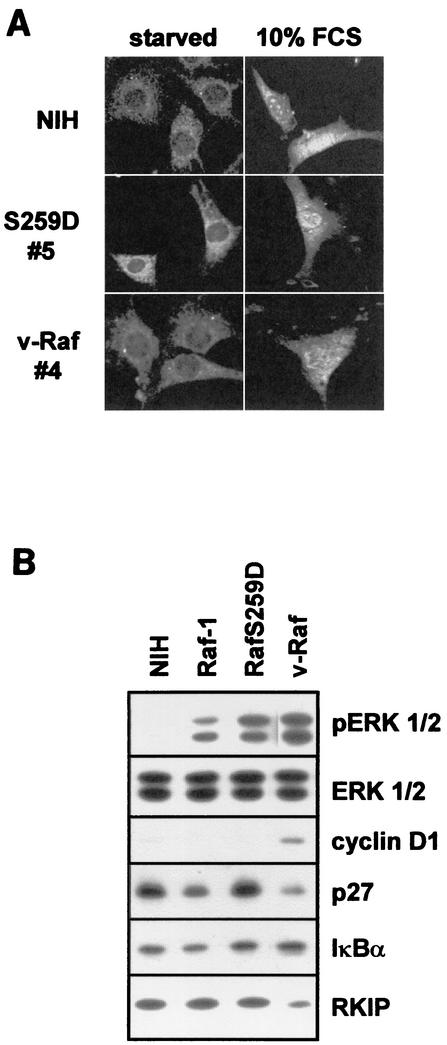

RKIP levels are lower in v-Raf cells than in S259D cells, but ERK nuclear translocation is normal.

Transformation by oncogenes requires sustained ERK activation and its translocation to the nucleus (25). To determine if ERK retains the ability to translocate to the nucleus in the v-Raf and RafS259D cells, we used a phospho-ERK antibody to detect the localization of active ERK (Fig. 8A). In serum-starved cells, active ERK was mainly cytosolic. Treatment with 10% FCS resulted in an increase in both cytosolic and nuclear staining for phospho-ERK in the v-Raf and RafS259D cells as well as in the parental cell line. These results indicate that the ability of activated ERK to translocate to the nucleus remains intact in both the v-Raf and RafS259D cells.

FIG. 8.

(A) ERK localization in selected Raf clones. Cells were serum starved (0.5% FCS) overnight and subsequently stimulated with 10% FCS for 30 min and then stained with an antibody specific for activated ERK. (B) ERK activation and expression of cyclin D1, p27, RKIP, and IκBα in the above (A) Raf clones. Lysates prepared from serum-starved cells were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

To explore the basis for the different characteristics of v-Raf and S259D cells, we measured the expression of several reported MEK/ERK targets and the modulator RKIP. As expected, serum deprivation led to a downregulation of cyclin D1 in wild-type cells and an increase in p27 levels. Interestingly, we were unable to detect p21 (results not shown), suggesting that p27 is the major cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor in our cells. The RafS259D cells responded to serum deprivation similarly to wild-type cells with respect to cyclin D1 and p27 expression. In contrast, v-Raf cells failed to upregulate p27 and continued to express cyclin D1 when they were serum starved, indicating that the ability of these cells to enter the cell cycle was no longer dependent on the presence of mitogens. Interestingly, the levels of RKIP, a protein recently shown to suppress BXB and v-Raf transformation (52), were clearly reduced in v-Raf cells but not in wild-type or RafS259D cells, suggesting that downregulation of RKIP may be a requirement for the transformed phenotype.

RafS259 mutants interfere with transformation by an activated MEK mutant.

To try and understand the inability of RafS259 mutants to drive malignant transformation, we examined two hypotheses. The first was that the RafS259 mutants failed to couple to another pathway(s) required for transformation. The second was that the mutants activated or coupled better to an inhibitory pathway(s). We examined the first possibility using genetic complementation assays. For this purpose we chose focus assays as easily quantified indicators of malignant transformation. Recent reports suggest that Raf-mediated transformation requires activation of the ubiquitous transcription factor NF-κB (45) and may also require phosphatidylinositol (PI) 3-kinase activity (14, 26). To see if the RafS259 mutants were defective in coupling to either of these pathways, we cotransfected the RafS259 mutants with constructs expressing p65 NF-κB or the activated p110 catalytic subunit of PI 3-kinase. In both cases, transformation was not rescued (results not shown).

To test our second hypothesis, we examined whether expression of the RafS259 mutants interfered with transformation induced by activated MEK protein MEK-DD (Fig. 9). NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with expression plasmids for MEK-DD alone or in combination with wild-type Raf-1 or RafS259 mutants, and focus induction was examined. The number of foci formed by MEK-DD was reduced when either of the RafS259 mutants was expressed, with RafS259A being a more potent inhibitor of transformation than RafS259D. Coexpression of wild-type Raf-1 caused a marginal reduction in MEK-DD-induced focus formation. In keeping with these data the RafS259 mutants were also able to inhibit transformation by activated Ras (results not shown). These results suggest that the RafS259 mutants may activate or more efficiently couple to a pathway(s) which interferes with transformation. However, this does not rule out the possibility that the mutants in addition may fail to couple to an activating pathway(s).

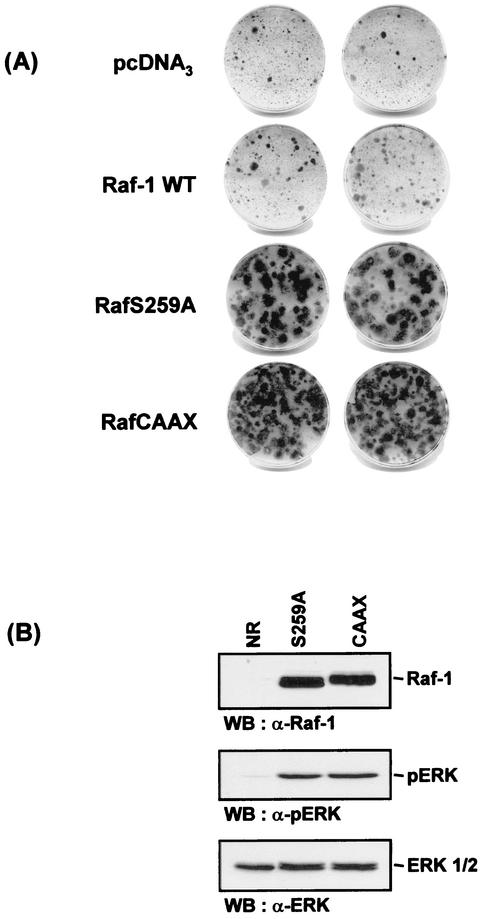

RafS259A induces proliferation of NR cells.

The chicken embryonic NR cell system has been shown to provide a sensitive readout of mitogenic signals (32). While proliferation is induced by the constitutive expression of activated oncogenes, continuous NR cell division also requires the presence of serum and is thus sustained by two different signals. To test for mitogenicity, we transfected NR cells dissected from 8-day-old chicken embryos with various Raf-1 constructs and then examined cultures for the presence of foci of proliferating cells 2 weeks after G418 selection (Fig. 10A). As reported previously wild-type Raf-1 was poorly mitogenic when overexpressed (31). In contrast, RafS259A clearly displayed a strong mitogenic capacity. It was, however, weaker than RafCAAX, a Raf-1 mutant rendered active by being tethered to the membrane. The foci formed by RafS259A appeared to be larger, because the RafCAAX cells were more transformed (more refringent with a smaller cytoplasm and a tendency to detach) than the RafS259A cells, which were more spread out (data not shown). RafS259A and RafCAAX activated ERK to similar extents in these cells, as measured by using phospho-ERK antibodies (Fig. 10B).

FIG. 10.

(A) Induction of NR cell proliferation by Raf proteins. NR cells were transfected with the indicated pCDNA3-derived Raf constructs as described in Materials and Methods. After selection with G418, foci of proliferating NR cells were stained with crystal violet. (B) ERK activation by Raf proteins. NR cells were transfected with the Raf constructs used in panel A. Lysates were prepared after passaging of proliferating foci and analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with antibodies against activated ERK (pERK), ERK, and FLAG. Untransfected NR cell cultures were used as the control.

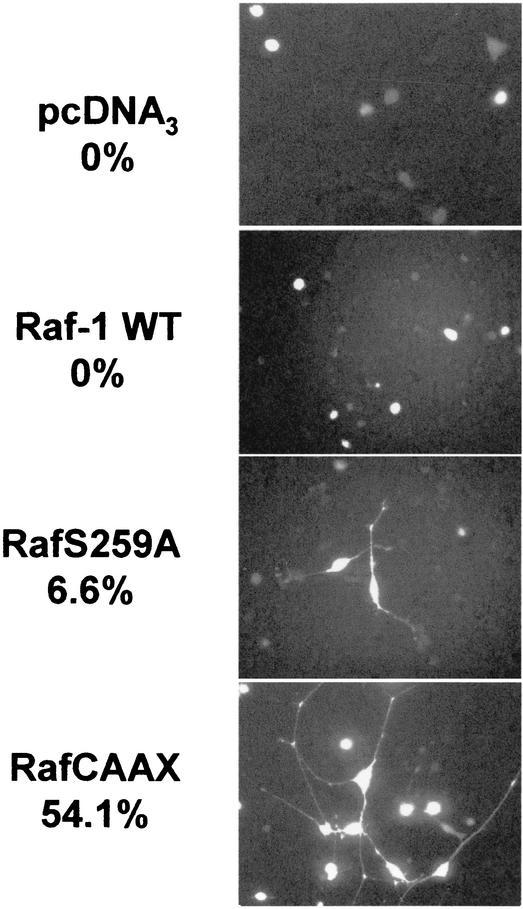

RafS259A is a poor inducer of PC12 cell differentiation.

In addition to promoting cellular transformation, activated forms of Raf-1 have been shown to cause differentiation of certain cell types. Activated Raf proteins have been shown to induce the formation of neurites in the PC12 cell line principally via the sustained activation of the MEK/ERK pathway (6). Since both RafCAAX and RafS259A activated ERK to similar levels, we expected that the overexpression of both proteins in PC12 cells would lead to neurite formation. Thus it was a surprise to find that, whereas RafCAAX induced the formation of neurites in approximately one-half of the transfected cells, RafS259A was a poor inducer of neurite formation (Fig. 11). Cells overexpressing wild-type Raf-1 failed to form neurites. These results indicate that RafS259A partially uncouples the differentiation of PC12 cells from ERK activation and that sustained activation of ERK signaling is not sufficient for the differentiation of these cells.

FIG. 11.

Induction of PC12 differentiation by Raf proteins. PC12 cells were cotransfected with the indicated pCDNA3-derived Raf constructs and the pEGFP-C3 reporter construct. The indicated percentages represent the ratios between green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive cells undergoing neurite outgrowth and the total number of GFP-positive transfected cells. WT, wild type.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have shown that serine 259 plays a crucial role in regulating signaling by the Raf-1 kinase. Dephosphorylation of S259 appears to be a requirement for Raf-1 activation, and its phosphorylation by kinases such as protein kinase A and protein kinase B/Akt interferes with Raf-1 activation (7, 8, 16, 19). Mutation of serine 259 has been consistently shown to elevate the kinase activity of Raf-1 (7, 30, 36, 54). Thus far, only one study, involving Drosophila melanogaster, has examined the biological consequences of this. Rommel et al. introduced an analogous mutation into Drosophila Raf (D-Raf) and found that the mutant increased R7 photoreceptor cell formation in the Drosophila eye (36). This process was ERK dependent, suggesting that this D-Raf mutant enhanced ERK signaling. Here we have investigated the biochemical and biological effects of Raf-1 serine 259 mutations in mammalian cells. Our results are intriguing, as they show that these mutations can dissociate MEK/ERK activation from malignant transformation and differentiation, but not proliferation.

Since Raf-1 is the cellular homologue of the retroviral v-raf oncogene, we initially focused on cell transformation. Mutation of serine 259 to either alanine or aspartic acid elevated the basal Raf-1 kinase activity in COS-1 and NIH 3T3 cells. In addition, these mutants induced a robust activation of MEK and ERK to an extent similar to that achieved by the v-Raf oncoprotein. As stimulation of the ERK pathway by activated MEK mutants has been reported to suffice for the transformation of NIH 3T3 cells (6, 24), we were surprised to find that RafS259D mutants were not tumorigenic and were largely inactive in several in vitro transformation assays. They altered cell morphology and accelerated proliferation but fared poorly in focus formation and soft-agar growth assays.

One interesting aspect of these studies was that we found absolutely no correlation between Raf protein expression levels, Raf kinase activity, and the extent of MEK activation in cells. This observation is reminiscent of a previous study which showed that MEK-mediated transformation did not correlate with the extent of ERK activation (1). As MEK-mediated transformation requires ERK to be localized in the nucleus (6), we also examined if ERK could translocate to the nucleus in the v-Raf and RafS259D cells and found this to be the case. These results suggest that the coupling between Raf and MEK, MEK and ERK, and ERK and its substrates is very carefully adjusted in cells. At present, these modulators are largely unknown. We have recently identified RKIP, a protein that can interfere with MEK activation by Raf-1 through disrupting the interaction between Raf-1 and its substrate MEK (52). Consequently, RKIP can suppress BXB- and v-Raf-induced transformation, but not transformation caused by activated MEK mutants (51). Our finding that RKIP expression was lower in v-Raf cells than in RafS259D cells with comparable ERK activity raises the possibility that RKIP downregulation plays a role in transformation. At first glimpse this seems to be in conflict with the observation that RafS259 is a very efficient MEK activator. However, as Yeung et al. have recently shown, RKIP can also suppress NF-κB activation by binding to and inhibiting IκB kinases (53). Thus, RKIP may impinge on transformation on multiple levels. In addition, our observation that RafS259 mutants suppress transformation by an activated MEK mutant makes it unlikely that RKIP levels alone are responsible for the transformation-attenuated phenotype of the RafS259 mutants.

Recent reports indicate that MEK-induced transformation requires autocrine growth factors (4, 44), which stimulate complementary pathways, such as the PI-3 kinase pathway. This may be related to a general requirement for PI-3 kinase activity for cell cycle progression. For instance, timed-microinjection experiments with dominant-negative proteins or neutralizing antibodies demonstrated that Ras activity is necessary throughout the whole G1 phase in order for DNA synthesis to occur in fibroblasts. The blockade of individual downstream Ras effectors revealed a transient requirement for Raf-1 early in G1, whereas PI-3 kinase activity was required throughout G1 (37). It has also been reported that Raf-mediated transformation requires the activation of NF-κB (45). Thus, RafS259 mutants could be defective in coupling to one or several of the complementary pathways. However, when we coexpressed the RafS259D mutant with either the p110 subunit of PI 3-kinase or p65 NF-κB, we were unable to rescue transformation. We also did not observe any differences in the levels of activation of Akt in the v-Raf and Raf S259D cells (data not shown). While this does not rule out the possibility that RafS259D is deficient in coupling to some other pathway required for transformation, our observation that the mutants can suppress MEK-DD-induced transformation suggests that the mutants are able to activate inhibitory pathways or feedback loops more efficiently than transforming Raf mutants. We presently do not know the nature of these inhibitory pathways, but one possibility is that the mutants prevent the production of the autocrine factors required for transformation. A number of studies have shown that Raf-1 may have an important antiapoptotic function(s) (3). In v-abl transformation, Raf-1 was reported to provide an ERK-independent survival signal which complemented c-myc in transformation (49). However, the contribution of such a survival function to Raf-1-mediated transformation is not presently clear. Our preliminary studies have shown no significant differences in the sensitivities of v-Raf and Raf S259D cells to serum-induced apoptosis (data not shown).

The intriguing findings with fibroblast transformation prompted us to examine other Raf-mediated processes which are thought to be dependent on activation of the MEK/ERK pathway, namely, proliferation of NR cells and differentiation of PC12 cells. The use of primary cultures of differentiating avian embryonic NR cells has been reported to be a sensitive model for the detection of mitogenic signals (32). In these cells, constitutive activation of the Raf-MEK/ERK pathway is a potent inducer of cell division. Thus we compared the proliferative potential of RafS259A to that of activated RafCAAX, and found that RafS259 and RafCAAX activated ERK to similar extents. The fact that both Raf-1 mutants were able to induce comparable levels of NR cell division indicates that mutation of serine 259 did not significantly impair the proliferative capacity of Raf-1, consistent with our growth curve data for the NIH 3T3 clones.

There is compelling evidence that the differentiation of PC12 cells into cells with a neuron-like phenotype requires sustained ERK signaling (6, 25, 46). Since both RafS259A and RafCAAX produce sustained ERK activation, we expected that the two proteins would stimulate PC12 cell differentiation to similar extents. Thus we were surprised to find that RafS259A was a poor inducer of neurite formation compared to RafCAAX. Previous studies have shown that both oncogenic Ras and oncogenic Raf promote neurite outgrowth in these cells by virtue of causing prolonged ERK activation. A similar effect was seen when activated MEK mutants were introduced, whereas interfering MEK mutants, which prevented ligand-induced ERK activation, block differentiation. We do not know why RafS259A performed so poorly in this assay, but these results together with the transformation data for NIH 3T3 cells argue that serine 259 plays a crucial role in governing the biological outcome of Raf-1 activation. The results described are provocative as they suggest the existence of at least one alternative Raf-1 effector pathway different from the MEK/ERK pathway. Serine 259 is a major binding site for 14-3-3 proteins, so it is possible that 14-3-3 provides the link to such a pathway. Clearly, understanding the basis of the biological phenotypes reported here may reveal new aspects of signaling by Raf-1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Karin, Michael Weber, Lewis Williams, Michael White, and Debbie Morrison for reagents.

This work was supported by Cancer Research U.K. and the Wilhelm Sander Stiftung to W.K., the Association for International Cancer Research to P.E.S., and the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (Comité des Yvelines) and Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (grant 4269) to A.E.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessandrini, A., H. Greulich, W. D. Huang, and R. L. Erikson. 1996. Mek1 phosphorylation site mutants activate Raf-1 in NIH 3T3 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271:31612-31618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, S., D. L. Davis, H. Dahlback, H. Jornvall, and D. W. Russell. 1989. Cloning, structure, and expression of the mitochondrial cytochrome P-450 sterol 26-hydroxylase, a bile acid biosynthetic enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 264:8222-8229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baccarini, M. 2002. An old kinase on a new path: Raf and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 9:783-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blalock, W. L., M. Pearce, L. S. Steelman, R. A. Franklin, S. A. McCarthy, H. Cherwinski, M. McMahon, and J. A. McCubrey. 2000. A conditionally-active form of MEK1 results in autocrine transformation of human and mouse hematopoietic cells. Oncogene 19:526-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonner, T., S. J. O'Brien, W. G. Nash, U. R. Rapp, C. C. Morton, and P. Leder. 1984. The human homologs of the raf (mil) oncogene are located on human chromosomes 3 and 4. Science 223:71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowley, S., H. Paterson, P. Kemp, and C. J. Marshall. 1994. Activation of MAP kinase kinase is necessary and sufficient for PC12 differentiation and for transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Cell 77:841-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhillon, A. S., S. Meikle, Z. Yazici, M. Eulitz, and W. Kolch. 2002. Regulation of Raf-1 activation and signalling by dephosphorylation. EMBO J. 21:64-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhillon, A. S., C. Pollock, H. Steen, P. E. Shaw, H. Mischak, and W. Kolch. 2002. Cyclic AMP-dependent kinase regulates Raf-1 kinase mainly by phosphorylation of serine 259. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3237-3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudley, D. T., L. Pang, S. J. Decker, A. J. Bridges, and A. R. Saltiel. 1995. A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7686-7689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumaz, N., Y. Light, and R. Marais. 2002. Cyclic AMP blocks cell growth through Raf-1-dependent and Raf-1-independent mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3717-3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Häfner, S., H. S. Adler, H. Mischak, P. Janosch, G. Heidecker, A. Wolfman, S. Pippig, M. Lohse, M. Ueffing, and W. Kolch. 1994. Mechanism of inhibition of Raf-1 by protein kinase A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:6696-6703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallek, M., K. Ando, M. Eder, K. Slattery, F. Ajchenbaum Cymbalista, and J. D. Griffin. 1994. Signal transduction of steel factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: differential regulation of transcription factor and G1 cyclin gene expression, and of proliferation in the human factor-dependent cell line MO7. Leukemia 8:740-748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heidecker, G., M. Huleihel, J. L. Cleveland, W. Kolch, T. W. Beck, P. Lloyd, T. Pawson, and U. R. Rapp. 1990. Mutational activation of c-raf-1 and definition of the minimal transforming sequence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:2503-2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu, Q., A. Klippel, A. J. Muslin, W. J. Fantl, and L. T. Williams. 1995. Ras-dependent induction of cellular responses by constitutively active phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase. Science 268:100-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huser, M., J. Luckett, A. Chiloeches, K. Mercer, M. Iwobi, S. Giblett, X. M. Sun, J. Brown, R. Marais, and C. Pritchard. 2001. MEK kinase activity is not necessary for Raf-1 function. EMBO J. 20:1940-1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaumot, M., and J. F. Hancock. 2001. Protein phosphatases 1 and 2A promote Raf-1 activation by regulating 14-3-3 interactions. Oncogene 20:3949-3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolch, W. 2000. Meaningful relationships: the regulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by protein interactions. Biochem. J. 351:289-305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kortenjann, M., and P. E. Shaw. 1995. Raf-1 kinase and ERK2 uncoupled from mitogenic signals in rat fibroblasts. Oncogene 11:2105-2112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubicek, M., M. Pacher, D. Abraham, K. Podar, M. Eulitz, and M. Baccarini. 2002. Dephosphorylation of Ser-259 regulates Raf-1 membrane association. J. Biol. Chem. 277:7913-7919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo, W. L., M. Abe, J. Rhee, E. M. Eves, S. A. McCarthy, M. Yan, D. J. Templeton, M. McMahon, and M. R. Rosner. 1996. Raf, but not MEK or ERK, is sufficient for differentiation of hippocampal neuronal cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1458-1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leevers, S. J., H. F. Paterson, and C. J. Marshall. 1994. Requirement for Ras in Raf activation is overcome by targeting Raf to the plasma membrane. Nature 369:411-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenormand, P., M. McMahon, and J. Pouysségur. 1996. Oncogenic Raf-1 activates p70 S6 kinase via a mitogen-activated protein kinase-independent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 271:15762-15768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majewski, M., M. Nieborowska-Skorska, P. Salomoni, A. Slupianek, K. Reiss, R. Trotta, B. Calabretta, and T. Skorski. 1999. Activation of mitochondrial Raf-1 is involved in the antiapoptotic effects of Akt. Cancer Res. 59:2815-2819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansour, S. J., J. M. Candia, K. K. Gloor, and N. G. Ahn. 1996. Constitutively active mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MAPKK1) and MAPKK2 mediate similar transcriptional and morphological responses. Cell Growth Differ. 7:243-250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall, C. J. 1995. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell 80:179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCubrey, J. A., J. T. Lee, L. S. Steelman, W. L. Blalock, P. W. Moye, F. Chang, M. Pearce, J. G. Shelton, M. K. White, R. A. Franklin, and S. C. Pohnert. 2001. Interactions between the PI3K and Raf signaling pathways can result in the transformation of hematopoietic cells. Cancer Detect. Prev. 25:375-393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikula, M., M. Schreiber, Z. Husak, L. Kucerova, J. Ruth, R. Wieser, K. Zatloukal, H. Beug, E. F. Wagner, and M. Baccarini. 2001. Embryonic lethality and fetal liver apoptosis in mice lacking the c-raf-1 gene. EMBO J. 20:1952-1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mineo, C., R. G. W. Anderson, and M. A. White. 1997. Physical association with Ras enhances activation of membrane-bound Raf (RafCAAX). J. Biol. Chem. 272:10345-10348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mischak, H., T. Seitz, P. Janosch, M. Eulitz, H. Steen, M. Schellerer, A. Philipp, and W. Kolch. 1996. Negative regulation of Raf-1 by phosphorylation of serine 621. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:5409-5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison, D. K., G. Heidecker, U. R. Rapp, and T. D. Copeland. 1993. Identification of the major phosphorylation sites of the Raf-1 kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:17309-17316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papin, C., A. Denouel-Galy, D. Laugier, G. Calothy, and A. Eychene. 1998. Modulation of kinase activity and oncogenic properties by alternative splicing reveals a novel regulatory mechanism for B-Raf. J. Biol. Chem. 273:24939-24947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peyssonnaux, C., S. Provot, M. P. Felder-Schmittbuhl, G. Calothy, and A. Eychène. 2000. Induction of postmitotic neuroretina cell proliferation by distinct Ras downstream signaling pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7068-7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porras, A., K. Muszynski, U. R. Rapp, and E. Santos. 1994. Dissociation between activation of Raf-1 kinase and the 42-kDa mitogen-activated protein kinase/90-kDa S6 kinase (MAPK/RSK) cascade in the insulin/Ras pathway of adipocytic differentiation of 3T3 L1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269:12741-12748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pumiglia, K. M., and S. J. Decker. 1997. Cell cycle arrest mediated by the MEK/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:448-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rapp, U. R., M. D. Goldsborough, G. E. Mark, T. I. Bonner, J. Groffen, F. H. Reynolds, Jr., and J. R. Stephenson. 1983. Structure and biological activity of v-raf, a unique oncogene transduced by a retrovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:4218-4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rommel, C., G. Radziwill, K. Moelling, and E. Hafen. 1997. Negative regulation of Raf activity by binding of 14-3-3 to the amino terminus of Raf in vivo. Mech. Dev. 64:95-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose, D. W., S. Xiao, T. S. Pillay, W. Kolch, and J. M. Olefsky. 1998. Prolonged vs transient roles for early cell cycle signaling components. Oncogene 17:889-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roy, S., A. Lane, J. Yan, R. McPherson, and J. F. Hancock. 1997. Activity of plasma membrane-recruited Raf-1 is regulated by Ras via the Raf zinc finger. J. Biol. Chem. 272:20139-20145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaeffer, H. J., and M. J. Weber. 1999. Mitogen-activated protein kinases: specific messages from ubiquitous messengers. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:2435-2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sewing, A., B. Wiseman, A. C. Lloyd, and H. Land. 1997. High-intensity Raf signal causes cell cycle arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5588-5597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanton, V. P., Jr., D. W. Nichols, A. P. Laudano, and G. M. Cooper. 1989. Definition of the human raf amino-terminal regulatory region by deletion mutagenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:639-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stokoe, D., S. G. Macdonald, K. Cadwallader, M. Symons, and J. F. Hancock. 1994. Activation of Raf as a result of recruitment to the plasma membrane. Science 264:1463-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Storm, S. M., U. Brennscheidt, G. Sithanandam, and U. R. Rapp. 1990. Raf oncogenes in carcinogenesis. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2:1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Treinies, I., H. F. Paterson, S. Hooper, R. Wilson, and C. J. Marshall. 1999. Activated MEK stimulates expression of AP-1 components independently of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) but requires a PI3-kinase signal to stimulate DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:321-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vale, T., T. T. Ngo, M. A. White, and P. E. Lipsky. 2001. Raf-induced transformation requires an interleukin 1 autocrine loop. Cancer Res. 61:602-607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaudry, D., P. J. Stork, P. Lazarovici, and L. E. Eiden. 2002. Signaling pathways for PC12 cell differentiation: making the right connections. Science 296:1648-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, H. G., U. R. Rapp, and J. C. Reed. 1996. Bcl-2 targets the protein kinase Raf-1 to mitochondria. Cell 87:629-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, S., R. N. Ghosh, and S. P. Chellappan. 1998. Raf-1 physically interacts with Rb and regulates its function: a link between mitogenic signaling and cell cycle regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:7487-7498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weissinger, E. M., G. Eissner, C. Grammer, S. Fackler, B. Haefner, L. S. Yoon, K. S. Lu, A. Bazarov, J. M. Sedivy, H. Mischak, and W. Kolch. 1997. Inhibition of the Raf-1 kinase by cyclic AMP agonists causes apoptosis of v-abl-transformed cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3229-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woods, D., D. Parry, H. Cherwinski, E. Bosch, E. Lees, and M. McMahon. 1997. Raf-induced proliferation or cell cycle arrest is determined by the level of Raf activity with arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5598-5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yeung, K., P. Janosch, B. McFerran, D. W. Rose, H. Mischak, J. M. Sedivy, and W. Kolch. 2000. Mechanism of suppression of the Raf/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by the Raf kinase inhibitor protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:3079-3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yeung, K., T. Seitz, S. Li, P. Janosch, B. McFerran, C. Kaiser, F. Fee, K. D. Katsanakis, D. W. Rose, H. Mischak, J. M. Sedivy, and W. Kolch. 1999. Suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity and MAP kinase signalling by RKIP. Nature 401:173-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yeung, K. C., D. W. Rose, A. S. Dhillon, D. Yaros, M. Gustafsson, D. Chatterjee, B. McFerran, J. Wyche, W. Kolch, and J. M. Sedivy. 2001. Raf kinase inhibitor protein interacts with NF-κB-inducing kinase and TAK1 and inhibits NF-κB activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7207-7217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zimmermann, S., and K. Moelling. 1999. Phosphorylation and regulation of raf by Akt (protein kinase B). Science 286:1741-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]