Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine patient preferences for addressing religion and spirituality in the medical encounter.

DESIGN

Multicenter survey verbally administered by trained research assistants. Survey items included questions on demographics, health status, health care utilization, functional status, spiritual well-being, and patient preference for religious/spiritual involvement in their own medical encounters and in hypothetical medical situations.

SETTING

Primary care clinics of 6 academic medical centers in 3 states (NC, Fla, Vt).

PATIENTS/PARTICIPANTS

Patients 18 years of age and older who were systematically selected from the waiting rooms of their primary care physicians.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Four hundred fifty-six patients participated in the study. One third of patients wanted to be asked about their religious beliefs during a routine office visit. Two thirds felt that physicians should be aware of their religious or spiritual beliefs. Patient agreement with physician spiritual interaction increased strongly with the severity of the illness setting, with 19% patient agreement with physician prayer in a routine office visit, 29% agreement in a hospitalized setting, and 50% agreement in a near-death scenario (P < .001). Patient interest in religious or spiritual interaction decreased when the intensity of the interaction moved from a simple discussion of spiritual issues (33% agree) to physician silent prayer (28% agree) to physician prayer with a patient (19% agree; P < .001). Ten percent of patients were willing to give up time spent on medical issues in an office visit setting to discuss religious/spiritual issues with their physician. After controlling for age, gender, marital status, education, spirituality score, and health care utilization, African-American subjects were more likely to accept this time trade-off (odds ratio, 4.9; confidence interval, 2.1 to 11.7).

CONCLUSION

Physicians should be aware that a substantial minority of patients desire spiritual interaction in routine office visits. When asked about specific prayer behaviors across a range of clinical scenarios, patient desire for spiritual interaction increased with increasing severity of illness setting and decreased when referring to more-intense spiritual interactions. For most patients, the routine office visit may not be the optimal setting for a physician-patient spiritual dialog.

Keywords: religion and medicine, physician-patient relations, primary health care

Research addressing the role of religion and spirituality in medical care has grown considerably over the last decade. This expanding body of literature has explored the potential positive impact of religion on various mental and physical health outcomes, including quality and length of life.1–9 Although limitations in research design and inadequate control of confounders temper the findings,10,11 the overall consistency of these results is provocative.

In general, the majority of patients would not be offended by gentle, open inquiry about their spiritual beliefs by physicians.12,13 Many patients want their spiritual needs addressed by their physician directly14,15 or by referral to a pastoral professional.16 Some believe in the healing power of prayer and feel that physicians should pray with their patients.15

Despite strong evidence of patients' desire for spiritual involvement in their medical care, previous studies have not pinpointed the types of behavior or settings that would be most appropriate for physician-patient dialog or interaction. In this study, our goal was to clarify patient preferences and to determine precisely how spirituality should be addressed in a variety of clinical circumstances. We also sought to identify characteristics associated with patients who are willing, in an office visit, to forego time dealing with medical problems for discussion of spiritual issues.

METHODS

Study Participants and Design

The Religion and Spirituality in the Medical Encounter Study (RESPECT) is a multicenter cross-sectional survey of patient and physician attitudes and preferences regarding religion and spirituality in the medical encounter. The study was conducted at 6 academic medical centers in 3 states (NC, Fla, Vt). These sites included inner-city clinics, suburban clinics, and a Veterans' Administration clinic. Participants were 18 years of age and older, and were systematically selected using a predetermined scheme (i.e., every third patient on the appointment schedule) from the waiting rooms of their primary care physicians. Patients were excluded if they were non–English-speaking, cognitively impaired, intoxicated, incarcerated, too ill to complete the survey, or if they refused. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the participating institutions. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Survey Instrument

Trained research assistants verbally administered the 112-item questionnaire that included items pertaining to demographics, health status, health care utilization, functional status, and religious/spiritual issues. The demographic information obtained included age, gender, race, marital status, education, income and health insurance. Health utilization was measured using self-report of hospitalizations over the previous 2 years and number of office and emergency room visits over the previous 1 year. Functional status was measured using the Medical Outcomes Trust Short Form (SF)-36.17 Religious affiliation and attendance at organized worship services were self-reported.

Religious and spiritual well-being were measured using the Spiritual Well Being (SWB) scale of Paloutzian and Ellison. The SWB scale was chosen because it is widely used in a variety of research contexts and a variety of populations. It is a measure of overall spiritual well-being in both a religious and an existential sense.18 The scale consists of 20 statements, each on a 6-point Likert scale. Scores may range from 20 to 120. It is easily understood and has clear scoring guidelines. The test-retest reliability and internal consistency of the SWB scale are documented.19

To assess patient attitudes, experiences, and preferences concerning religion and spirituality in the medical encounter, items were developed for which subjects expressed their level of agreement or disagreement using a 5-point Likert scale. Specific hypothetical clinical scenarios across a range of settings (office visit, hospital setting, death-and-dying situation) and specific religious activities (simple physician inquiry about religious and spiritual issues, physician silent prayer for a patient, physician active prayer with a patient) were included. See Appendix A for sample questions from the survey.

We were particularly interested in the relative value patients place on spiritual discussion with their physician. Working from the assumption that office visit time is fixed and that time spent discussing spiritual issues would detract from time spent on medical issues, we asked whether subjects would be willing to forego time spent on medical issues for time spent discussing spiritual or religious issues. The outcome variable analyzed was patient agreement with this trade-off.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to tabulate patient characteristics, attitudes, and experiences. We used Pearson's χ2 test, Fisher's exact test or Student's t test to examine bivariate associations between patient characteristics and the question that measured patients' preference for trading medical time for spiritual discussion. Likert scales were dichotomized to agreement and strong agreement representing “agree” and all remaining answers representing “other.” For the multivariable analyses, we categorized the SWB scale responses into 3 groups.

Multivariable analysis was performed using logistic regression. The outcome variable analyzed was the questionnaire item regarding patient willingness to forego time spent on medical problems (“agree” versus “other”). The independent variables included age, gender, marital status, race, education, SWB score, and medical utilization. All analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software, release 6 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex).

RESULTS

Five hundred forty-two patients were approached, with 456 (84%) agreeing to participate. The most common reasons cited by patients for refusal were “time constraints” and “feeling too ill.” No patients were excluded for cognitive impairment or intoxication. The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The study population represents patients from a variety of settings, including urban indigent clinics, a Veterans' Administration clinic and suburban practices. Almost half of the subjects were African American, compared to 12.1% of the U.S. population. About half were below $20,000 annual household income. The Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) of the SF-36 measure of functional status demonstrate a population with lower functional status than U.S. population norms, as expected for patients seeking care in an internal medicine setting. The PCS and MCS scores are similar to those seen in a U.S. population with diabetes.17

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N = 456)

| Characteristic | Mean or Percent |

|---|---|

| Mean age, y (range) | 52.3 y (18 to 86) |

| Gender, % | |

| Male | 44 |

| Female | 56 |

| Marital status, % | |

| Single | 25 |

| Married | 44 |

| Divorced/widowed | 31 |

| Race, % | |

| White | 53 |

| African American | 43 |

| Other | 4 |

| Religion, % | |

| Protestant | 60 |

| Catholic | 10 |

| Jewish | 1 |

| Muslim | <1 |

| Mormon | <1 |

| Christian Science | <1 |

| Buddhist | <1 |

| Jehovah's Witness | <1 |

| Agnostic or Atheist or No religion | 11 |

| Not specified | 16 |

| Education, % | |

| Less than high school | 28 |

| High school graduate | 28 |

| Some college or greater | 44 |

| Insurance, % | |

| None | 24 |

| Private | 28 |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 41 |

| Other | 7 |

| Annual household income $, % | |

| <10,000 | 28 |

| 10–39,000 | 44 |

| ≥40,000 | 21 |

| Not reported | 7 |

| Overnight hospitalizations within 1 y, % | |

| None | 53 |

| One or more | 47 |

| Functional status, mean ±SD | |

| SF-36 Physical Component Summary (PCS) | 39.5 ± 13.0 |

| SF-36 Mental Component Summary (MCS) | 49.7 ± 11.5 |

| Spiritual Well Being score, mean ±SD | 97.4 ± 16.8 |

| 20–80, % | 19 |

| 81–109, % | 46 |

| 110–120, % | 35 |

| Attendance at organized worship service within past y, % | |

| None | 22 |

| <1/wk | 61 |

| ≥1/wk | 17 |

Although many religions are represented, the majority of the sample are Christian, with 16% of subjects not specifying a religion. The mean SWB score was 97.4 with a standard deviation of 16.8. This is comparable to previous studies in medical outpatients.19

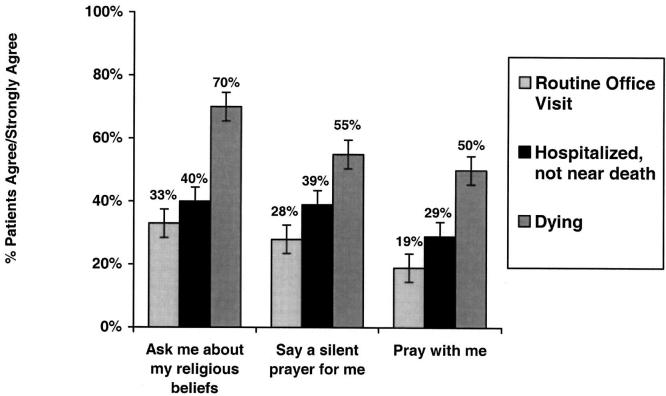

Sixty-six percent of the respondents felt that physicians should be aware of their patients' religious and spiritual beliefs. Patient preferences for specific spiritual behaviors in various clinical settings are represented in Figure 1. The first cluster of bars shows that as the severity of the illness setting increases, the proportion of patients welcoming a spiritual inquiry increases from 33% in an office visit to 40% in a hospitalization setting to 70% in a death-and-dying setting. Looking across the 3 clusters of spiritual activity shown along the x-axis, from physician inquiry to physician silent prayer to physician active prayer with a patient, the proportion of patients who agree that each behavior is appropriate decreases. This relationship is similar in all three of the illness settings. Less than one fifth of patients would agree that active physician prayer in an office visit is appropriate. On the other hand, 50% of patients would find active prayer acceptable in a terminal illness situation.

FIGURE 1.

Patients' preferences for religious involvement by their physician.

We wanted to explore the concept of patients' willingness to forego “medical time” for “spiritual time” in the medical encounter. When presented with the specific statement, “I want my doctor to discuss spiritual issues with me, even if it means spending less time on my medical problems,” only 10% of those surveyed were willing to make this trade-off, while 12% were neutral and 78% opposed. In Table 2, we show bivariate associations for this survey item regarding patients' willingness to forego time discussing spiritual issues. Patients with lower socioeconomic status (as measured by education and income), those with more-frequent worship attendance, and African Americans were more likely to agree that spending time on spiritual issues is worth foregoing time spent on medical issues. The SF-36 PCS and MCS scores were similar in the 2 subject groups (Mean PCS = 39.5 Other versus 39.2 Agree [P = .88] and mean MCS = 51.7 Other versus 49.5 Agree [P = .25]).

Table 2.

Bivariate Associations With Time Trade-off Statement (“I want my doctor to discuss spiritual issues with me even if it means spending less time on medical issues”)

| Characteristic | n | Agree, % | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .12 | ||

| <50 years | 188 | 6 | |

| ≥50 years | 264 | 13 | |

| Gender | .80 | ||

| Female | 253 | 10 | |

| Male | 198 | 10 | |

| Marital status | .48 | ||

| Married | 199 | 10 | |

| Single | 109 | 13 | |

| Divorced | 92 | 6 | |

| Widowed | 50 | 12 | |

| Location (state) | .71 | ||

| NC | 298 | 11 | |

| Fla | 125 | 9 | |

| Vt | 29 | 7 | |

| Race | <.001 | ||

| African American | 193 | 17 | |

| White | 241 | 5 | |

| Religion | .04† | ||

| Protestant | 267 | 11 | |

| Catholic | 46 | 0 | |

| Jewish | 6 | 0 | |

| Muslim | 2 | 50 | |

| Mormon | 3 | 0 | |

| Christian Science | 1 | 0 | |

| Buddhist | 1 | 0 | |

| Jehovah's Witness | 4 | 0 | |

| Agnostic/Atheist/None | 48 | 4 | |

| Not specified | 70 | 19 | |

| Organized worship attendance | .001 | ||

| None | 99 | 5 | |

| <1/wk | 168 | 6 | |

| ≥1/wk | 182 | 16 | |

| Education | <.001 | ||

| Less than high school | 125 | 20 | |

| High school graduate | 126 | 6 | |

| Some college or greater | 201 | 7 | |

| Insurance status | .64 | ||

| None | 105 | 9 | |

| Any | 337 | 10 | |

| Household income, $ | 0.01 | ||

| <10,000 | 128 | 16 | |

| 10–39,000 | 201 | 7 | |

| ≥40,000 | 95 | 5 | |

| SWB scale score | 0.07 | ||

| <80 | 101 | 3 | |

| 81–115 | 275 | 11 | |

| >115 | 76 | 12 |

χ2, except where noted.

Fisher's exact test.

In our logistic regression model, African-American race was the only characteristic that remained significantly associated with a willingness to trade off medical time in an office visit, while controlling for age, gender, marital status, education, SWB score, and health care utilization (odds ratio, 4.9; confidence interval, 2.1 to 11.7).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that although patients express a general interest in spiritual dialog with their physicians, only a minority would welcome spiritual interaction in an office visit setting and fewer than 10% would forego time spent discussing medical issues for a discussion of spirituality. Sixty-six percent of our subjects feel that their physician should generally be aware of their religious and spiritual beliefs, but only 33% would welcome physician inquiry into their spiritual beliefs in an office setting. The only scenario in which more than 50% of patients agree that any form of physician spiritual interaction is appropriate was the setting where a patient is near death.

The finding that two thirds of our subjects feel their physicians should generally be aware of their religious and spiritual beliefs is consistent with Oyama and Koenig's findings that 73% of outpatient subjects indicated that physicians should have knowledge of their patients' religious beliefs.20 The finding that 33% of our subjects agree that physicians should inquire about religious or spiritual beliefs in the office setting is also consistent with previous research with smaller single-institution samples. Maugans and Wadland, in a survey of 135 outpatients in Vermont, found that 30% of respondents felt that their physicians should address religious issues with them.14 Daaleman and Nease, in a survey of 80 family practice patients in Kansas, found that 41% of their sample felt doctors should ask about religion and personal faith.16 King and Bushwick, in interviews with 203 medical inpatients, found that 77% felt that physicians should consider their patients' spiritual needs and 37% wanted more physician discussion of their religious beliefs.15

Previous studies have not examined the range of clinical scenarios (office setting, hospitalization setting, and terminal illness setting) and religious behaviors (physician inquiry, physician silent prayer, and physician active prayer) that we have addressed. Figure 1 illustrates that as the severity of the illness setting increases, patient interest in a spiritual dialog increases. In an office visit setting, fewer than 20% of patients would welcome physician-patient prayer, whereas in our death-and-dying scenario, 50% of patients welcomed active prayer with their physician and 70% agreed with physician inquiry into their religious or spiritual beliefs. This is consistent with our expectations that the level of spiritual concern would increase as patients face a graver illness. It is only in our terminal illness scenario, in which issues of mortality, faith, and coping are critically important, that more than half the patients welcome any level of religious or spiritual interaction. Several studies have examined issues regarding the spiritual preferences of gravely ill patients. Kaldjian et al., in a study of 90 inpatients with HIV or AIDS, found that 46% of their patients wanted to pray with their physicians.21 Ehman et al. found that 45% of patients in an outpatient pulmonary clinic have spiritual or religious beliefs that would influence medical decisions if they were to become gravely ill.12

We have also demonstrated that as the intensity of the interaction moves from physician inquiry about patient beliefs to physician silent prayer to physician-patient prayer, the proportion of patients who would welcome religious engagement decreases (Fig. 1). For example, in the hospitalization scenario, the proportion of patients who agree with physician interaction decreases from 40% for physician inquiry to 39% for physician silent prayer to 29% for physician-patient prayer. This latter proportion is less than that found in the King and Bushwick study of hospitalized patients, where up to 48% wanted their physician to pray with them.15

Despite the relatively high level of patient general interest in spiritual interaction, surveys of physician behavior have shown that doctors rarely discuss spirituality with their patients15,22 or refer them to pastoral professionals.23–25 Reasons cited by physicians for not addressing spiritual issues include: a fear of projecting their own beliefs onto patients,14,23,24 lack of time or training,24 difficulty in identifying those who would welcome discussion,24 assumption that those in need would self refer,23 and lack of the physician's own religious belief.23 The primary care office setting is one in which physicians may feel overburdened with competing demands to address a variety of issues including: symptoms, screening and prevention, psychosocial problems, family violence, drug and alcohol abuse, preferences for care at the end of life, and others. Time pressures are important contributors to physician job dissatisfaction.26,27

To further explore this gap between patient interest and physician behavior, we developed a scenario that we felt was representative of outpatient clinical practice, in which we asked patients if they would be willing to forego valuable minutes of an office visit for a discussion of spiritual issues. Only 10% of patients were willing to make this trade-off. Our findings reinforce that the routine office visit may not be the optimal time and place for these discussions. Although we have not addressed this issue directly, the hospital setting may offer several advantages, such as: less time pressure, a greater opportunity to involve family and other members of the treatment team, including clergy, and an opportunity to re-address issues over consecutive daily visits.

In addition to examining the setting of a patient encounter, a physician could look to patient characteristics to try to gauge how best to incorporate a spiritual discussion into practice. Daaleman and Nease found that patients' frequency of religious service attendance (at least monthly) predicted their acceptance of physician inquiry into their religion and personal faith and acceptance of physician referral to pastoral professionals for spiritual problems.16 Levin et al., using data from 4 national surveys of religiosity, found a positive association between African-American race and religiosity, even after controlling for a wide variety of demographic factors.28 Our finding that African-American race is an important patient characteristic in the approach to spiritual issues is consistent with this and other findings of racial differences in religiosity.29,30 We would suggest that approaches to addressing spirituality should be done in a culturally competent fashion and should avoid racial or cultural stereotyping.

Our study population is one of the largest and most diverse on this topic, covering a wide variety of patients, including veteran Americans and the urban underserved. We feel that it is representative of patients seen in general internal medicine settings in the United States. This is the first survey instrument to explore in detail how patients and physicians might concretely interact around spiritual issues.

A few limitations in this study must be noted. Although our patient population reflects a wide range of ages and socioeconomic and geographic backgrounds and is representative of populations seen in many medical centers, it is still drawn heavily from the southeastern United States. Additionally, our patient population was predominantly Protestant. The preferences reported here were obtained from hypothetical scenarios outlined in the survey and may not represent patients' actual behaviors when facing any of these situations.

Our study provides evidence to support the concept that proper timing and a patient-centered approach are important elements in taking a spiritual history, as suggested by Koenig.31 A variety of spiritual assessments and questionnaires have been proposed as aids to the practicing physician for exploring the broad dimensions of spirituality, although none of these tools has been tested prospectively.13,32–34 Future research is needed to explore the overlapping and intersecting roles of physicians, clergy, and other faith-based social support in the community and in the hospital. Further work is also needed to test the feasibility and acceptability of incorporating specific spiritual assessment tools into appropriate clinical settings. We hope that our results have highlighted the importance of assessing these approaches across a range of settings in which patient acceptability may vary considerably.

CONCLUSIONS

Physicians should be aware that a substantial minority of patients desire spiritual interaction in routine office visits. When patients were asked about specific prayer behaviors across a range of clinical scenarios, patient desire for spiritual interaction increased with increasing severity of illness setting and decreased when referring to more-intense spiritual interactions. For most patients, the routine office visit may not be the optimal setting for a physician-patient spiritual dialog.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tim Carey and Bill Miller for their contributions in reviewing and editing the manuscript, and the patients and physicians who completed the survey.

This study was supported by the UNC General Internal Medicine Faculty Development Fellowship Program, which is funded by Health Resources and Services Administration grant 5-D08-HP54004. Additional support was provided by grants from the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Health Services Foundation, Inc., the University of Florida College of Medicine Education Center, and the Moses Cone Medical Education Research Committee.

APPENDIX A

Sample Questions from the Religion and Spirituality in the Medical Encounter Study

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My doctor should not play a role in my spiritual or religious life. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My doctor should be aware of my religious or spiritual beliefs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My doctor should ask me about my religious or spiritual beliefs during a routine office visit. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| If I am near death, my doctor should ask me about my religious or spiritual beliefs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| If I am hospitalized, but not near death, my doctor should ask me about my religious or spiritual beliefs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My doctor should say a silent prayer for me during a routine office visit. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| My doctor should pray with me during a routine office visit. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| If I were in the hospital, my doctor should say a silent prayer for me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| If I were in the hospital, my doctor should pray with me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| If I am dying, my doctor should say a silent prayer for me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| If I am dying, my doctor should pray with me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| It is important to me that my doctor has strong spiritual beliefs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

REFERENCES

- 1.Byrd RC. Positive therapeutic effects of intercessory prayer in a coronary care unit population. South Med J. 1988;81:826–9. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris WS, Gowda M, Kolb JW, Strychacz CP, Vacek JL, Jones PG. A randomized, controlled trial of the effects of remote, intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients admitted to the coronary care unit. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2273–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.19.2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, George LK, Hays JC, Larson DB, Blazer DG. Attendance at religious services, interleukin-6, and other biological parameters of immune function in older adults. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27:233–50. doi: 10.2190/40NF-Q9Y2-0GG7-4WH6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koenig HG, George LK, Larson DB, McCullough ME, Branch PS, Kuchibhatla M. Depressive symptoms and nine-year survival of 1,001 male veterans hospitalized with medical illness. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;7:124–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koenig HG, Hays JC, Larson DB, George LK, Cohen HJ, McCullough ME. Does religious attendance prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3,968 older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M370–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.7.m370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig HG, George LK, Peterson BL. Religiosity and remission of depression in medically ill older patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:536–42. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.4.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levin JS, Chatters LM. Religion, health, and psychological well-being in older adults: findings from three national surveys. J Aging Health. 1998;10:504–31. doi: 10.1177/089826439801000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthews DA, Larson DB. An Annotated Bibliography of Clinical Research on Spiritual Subjects. Vol III. Rockville, Md: National Institute for Healthcare Research; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:957–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson DB, Koenig HG. Is God good for your health? The role of spirituality in medical care. Cleve Clin J Med. 2000;67:80–4. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.67.2.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sloan RP, Bagiella E, Powell T. Religion, spirituality, and medicine. Lancet. 1999;353:664–67. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07376-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehman JW, Ott BB, Short TH, Ciampa RC, Hansen-Flaschen J. Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1803–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maugans TA. The SPIRITual history. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:11–6. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maugans TA, Wadland WC. Religion and family medicine: a survey of physicians and patients. J Fam Pract. 1991;32:210–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King DE, Bushwick B. Beliefs and attitudes of hospital inpatients about faith healing and prayer. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:349–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daaleman TP, Nease DE., Jr Patient attitudes regarding physician inquiry into spiritual and religious issues. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:564–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User's Manual. Boston, Mass: Health Assessment Lab; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paloutzian RF, Ellison CW. Manual for the Spiritual Well Being Scale. Nyack, NY: Life Advance, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bufford RK, Paloutzian RF, Ellison CW. Norms for the spiritual well being scale. J Psychol Theol. 1991;19:35–48. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oyama O, Koenig HG. Religious beliefs and practices in family medicine. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:431–5. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.5.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaldjian LC, Jekel JF, Friedland G. End-of-life decisions in HIV-positive patients: the role of spiritual beliefs. AIDS. 1998;12:103–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson JM, Anderson LJ, Felsenthal G. Pastoral needs for support within an inpatient rehabilitation unit. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:574–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones AW. A survey of general practitioners' attitudes to the involvement of clergy in patient care. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40:280–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellis MR, Vinson DC, Ewigman B. Addressing spiritual concerns of patients: family physicians' attitudes and practices. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daaleman TP, Frey B. Prevalence and patterns of physician referral to clergy and pastoral care providers. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:548–53. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.6.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray A, Montgomery JE, Chang H, Rogers WH, Inui T, Safran DG. Doctor discontent. A comparison of physician satisfaction in different delivery system settings, 1986 and 1997. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:452–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007452.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, et al. Managed care, time pressure, and physician job satisfaction: results from the physician worklife study. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:441–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.05239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin JS, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Race and gender differences in religiosity among older adults: findings from four national surveys. J Gerontol. 1994;49:S137–45. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koenig HG. Religious attitudes and practices of hospitalized medically ill older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:213–24. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199804)13:4<213::aid-gps755>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD. Advances in the measurement of religiosity among older African Americans: implications for health and mental health researchers. J Mental Health Aging. 2001;7:181–200. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koenig HG. Spiritual assessment in medical practice. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthews DA, McCullough ME, Larson DB, Koenig HG, Swyers JP, Milano MG. Religious commitment and health status: a review of the research and implications for family medicine. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:118–24. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anandarajah G, Hight E. Spirituality and medical practice: using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:81–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo B, Ruston D, Kates LW, et al. Discussing religious and spiritual issues at the end of life: a practical guide for physicians. JAMA. 2001;287:749–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]