Abstract

OBJECTIVE

It has been shown that greater physician experience in the care of persons with AIDS prolongs survival, but how more experienced primary care physicians achieve better outcomes is not known.

DESIGN/SETTING/PATIENTS

Retrospective cohort study of HIV-infected patients enrolled in a large staff-model health maintenance organization from 1990 through 1999.

MEASUREMENTS

Adjusted odds of medical service delivery and adjusted hazard ratio of death by physician experience level (least, moderate, most) and service utilization.

MAIN RESULTS

Primary care delivery by physicians with greater AIDS experience was associated with improved survival. After controlling for disease severity, patients cared for by the most experienced physicians were twice as likely to receive a primary care visit in a given month compared with patients of the least and moderately experienced physicians (P < .01). Patients of the least experienced physicians received the lowest level of outpatient pharmacy and laboratory services (P < .001) and were half as likely to have a specialty care visit compared with patients of the most and moderately experienced physicians (P < .05). Patients who received infrequent primary care visits by the least experienced physicians were 15.3 times more likely to die than patients of the most experienced physicians (P = .02). There was a significant increase in primary care services delivered to the population of HIV-infected patients receiving care in 1999, when highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was in general use, compared with the time period prior to the introduction of HAART.

CONCLUSIONS

Primary care delivery by physicians with greater HIV experience contributes to improved patient outcomes.

Keywords: HIV, outcome and process assessment health care, physician's practice patterns

Greater experience among primary care physicians in the care of persons with AIDS improves survival.1 Patients of more experienced physicians have been shown to be more likely to receive appropriate and timely prophylaxis against Pneumocystiscarinii pneumonia (PCP) and measurement of CD4 cell count level.1 While the survival benefit of PCP prophylaxis is clear,2,3 it is not known whether more frequent CD4 cell count monitoring results from closer outpatient follow-up by more experienced physicians and if such differences in the delivery of medical care account for the improvement in patient outcomes.

The provision of medical care for persons with HIV infection in the United States shifted from inpatient to outpatient setting early in the epidemic.4,5 Ambulatory care largely supplanted rather than simply augmented hospital care for patients with HIV disease,6 a pattern now common among patients with other chronic conditions. Thus, the delivery of care to patients in the ambulatory setting may significantly impact clinical outcomes. Evidence supports the health advantages of continuous primary care provided to patients with chronic disease.7–21 Successful interventions that improve outcomes for chronically ill patients emphasize regularly scheduled primary care and ready access to ancillary services and specialty expertise.12–21

While clinical information regarding inpatient care is routinely captured in hospital administrative billing systems, outpatient care is often provided in multiple settings over many years. Thus, longitudinal information about treatment and outcomes for individual patients is difficult to characterize.6 Estimates of the overall cost and utilization of inpatient and outpatient services for persons with HIV disease have been projected from patient interviews, medical chart review, and claims data.5,22–27 However, examination of the effect of medical care delivery on outcomes has been limited to studies of hospital care and in-hospital mortality.28–32 This study was conducted to determine whether physician experience level is associated with differences in the delivery of medical services across all settings of care, and if patterns of delivery, such as the frequency of primary care visits, affect patient outcomes.

METHODS

Study Setting

The study cohort was selected from the enrollee population of Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound (GHC), Seattle, Washington. GHC is a staff-model HMO that provides comprehensive medical care for a fixed, prepaid fee to approximately 500,000 individuals in western Washington, the majority of whom have their premiums paid by their employers. Primary care physicians manage both the outpatient and inpatient care for defined groups of patients. Referrals for specialty consultation and ancillary services are at the discretion of the primary care physician to support the overall management of care, and there are no financial incentives to limit referrals or hospitalizations. The care of HIV-infected individuals is distributed among all primary care physicians in this generalist-based model of care. Insurance coverage for patients with AIDS is maintained through several financial arrangements that extend beyond the end of their employment; as a result, less than 3 percent of these patients leave GHC for reasons other than death.

Study Patients

We identified all patients enrolled at GHC in whom first AIDS-defining illnesses were diagnosed from 1984 through mid-1994 using entry criteria described previously.1 Four patients were excluded because their primary care physician changed within a year prior to their diagnosis of AIDS or thereafter, and 3 were excluded because their primary care physician had subspecialty training. Of these 403 adult male patients, 197 were enrolled after January 1990, when utilization data were first automated in the GHC system and included in the analysis. Review of medical records enabled criteria for AIDS-defining diagnoses to be applied to all cases consistently. All patients had serologically confirmed HIV infection and were men who had male sexual contact as a risk factor for HIV transmission. We identified all HIV-infected patients enrolled at GHC who received care in 1996 and 1999; these patients were included in the analysis of medical care utilization during these time periods.

Study Physicians

Eighty-three physicians provided primary care for the 197 patients with AIDS; 87% of these physicians were trained in family medicine or general practice, and 13% in internal medicine. We defined physicians' level of experience with AIDS care accounting for medical school, residency, and practice experience with AIDS care.1 Estimates for medical school and residency experience were developed from the AIDS incidence rates in the metropolitan area where physicians trained and the year training was completed. Practice experience was defined as the cumulative number of patients with AIDS whose care a physician had managed at the time a patient in the physician's practice was diagnosed with AIDS; the new patient was included in this total. As each patient entered the cohort, he was identified as his physician's first, second to fifth, or sixth or subsequent patient with AIDS. Some physicians graduated from lower to higher experience categories during the study period as they accumulated patients with AIDS. Therefore, a physician may have been assigned to different experience categories for patients diagnosed in her/his practice at different times. Medical school experience was redundant with residency experience for the physicians in our study. Thus, we combined residency and practice experience to define 3 levels of physician experience with AIDS care: least, moderate, and most. By the end of the study period, 25% of physicians remained in the least experienced category, 49% acquired moderate experience, and 25% had acquired the most experience. Individual physicians cared for a total of 1 to 21 patients with AIDS.

Sources of Data

We obtained information on the patients in the study, including demographic data, AIDS-defining diagnosis and date of diagnosis, risk factors for HIV transmission, and date on which care from GHC ended (because of death or transfer from the HMO) from the GHC HIV/AIDS Surveillance Database. Dates of death were confirmed by cross matching with the Washington State vital records. Personnel records provided information on the study physicians. We obtained health care utilization and cost data from the Decision Support System (DSS), implemented at GHC in 1989 to provide standardized data for all health care provided to members. Systematic verification of DSS data is performed both internally and through independent audits.

Statistical Analysis

Physician Experience Level and Medical Care Utilization

We used a generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach to logistic regression to examine the probability of utilizing medical services in a given month (including a primary care visit, a specialty care visit, a home health/hospice care visit, or a hospitalization) controlling for correlation between individual observations.33,34 In our data, correlation between individual observations could arise from 2 sources—observations on individuals with the same physician and repeated observations of the same individual. The GEE methodology developed by Heagerty and Zeger33 allowed us to account for 2 sources of correlation simultaneously. This analysis indicated that within-patient correlation was significant and declined smoothly with increasing time between the observations. However, there was no significant correlation between observations for individuals with the same physician; thus, only within-patient correlations were included in the final analysis.

Previous studies have shown that utilization of services and costs of care among patients with AIDS are significantly higher at the end of life,35–37 and are probably higher immediately after the diagnosis of a clinical AIDS-defining illness. To control for potential confounding by time period of care, we included a variable in the analysis to distinguish the AIDS diagnosis period (3-month period immediately following the diagnosis of a patient's AIDS-defining illness) and the end-of-life period (3-month period prior to death) from the interim period (time between AIDS diagnosis and end of life). Severity of illness at study entry was determined by the severity of AIDS-defining illness,38 and CD4 cell count was categorized into 4 levels (≥200/mm3, 100–199/mm3, 50–99/mm3, and <50/mm3). Increasing severity was accounted for by the number of months since the diagnosis of AIDS.

To assess both the volume and intensity of medical services provided (i.e., a single computed tomography scan is more intensive and thus, more costly than a plain radiograph), we computed the mean monthly cost per patient of medical services by physician experience level for the cohort of AIDS patients and for the total population of HIV-infected patients receiving care in the study setting in 1996 and 1999. Because cost data were not normally distributed, the 95% confidence intervals for the means and P values for differences within means were calculated using bootstrap procedures.39 Costs were inflated to 1999 dollars. We used S-PLUS software (MathSoft, Inc., Seattle, Wash) to perform the GEE logistic regression analysis and the analysis of cost data.

Medical Care Utilization and Survival

We used Kaplan-Meier product-limit survival analysis to estimate median survival times overall and by physician experience level.40 Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of death according to physician experience category, the severity of AIDS-defining illness, the CD4 cell count category, the rates of primary care and specialty care visits, hospitalization, and use of pharmacy, laboratory, and radiology services were estimated with Cox proportional-hazards survival analysis.41,42 We required that patients have at least 4 months of medical service utilization; 18 patients who did not meet this criterion because they died or were right-censored were omitted from the analysis (N = 179).

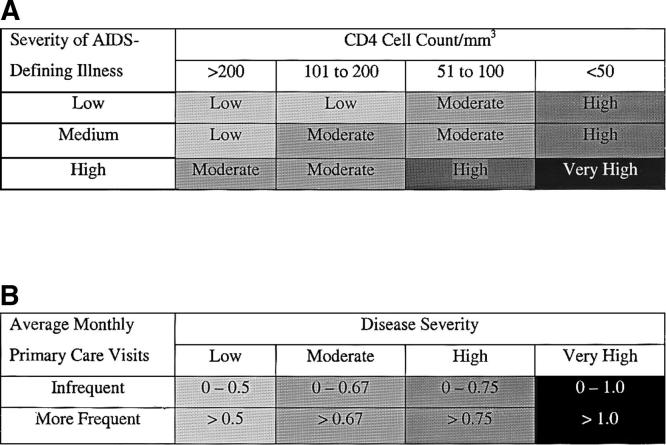

Like other models of utilization, ours assumed that primary care visits must be sufficiently frequent to be high in continuity.9,11,12,18,43 Infrequent primary care visits reflect a less than optimal pattern of care for patients at advanced stages of HIV disease with clinical AIDS. To examine the effect of primary care utilization on survival, we categorized the frequency of primary care visits into 2 levels (infrequent and more frequent)7,12 as shown in Figure 1. Interaction terms captured the joint effect of primary care visit frequency and physician experience level. Hospital/hospice utilization was significantly associated with higher risk of death in exploratory analyses and was included in the model to account for increased disease severity during the study period. Measures of specialty care and ancillary service use were collinear with hospital/hospice utilization and thus omitted from the final survival analysis. We used SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) to perform the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional-hazards analysis. Two-tailed P values of .05 or less were considered to indicate significance in all statistical tests.

FIGURE 1.

Classification of primary care utilization by disease severity and visit frequency. (A) Classification of disease severity at time of the diagnosis of AIDS. Patients were categorized into 4 levels of disease severity (low, moderate, high, and very high) at time of the diagnosis of AIDS based on CD4 cell count level and severity of AIDS-defining illness. The 4 categories of disease severity were associated with distinct levels of risk. Patients classified with very high, high, and moderate disease severity had a relative risk of death of 9.1, 2.9, (P < .0001), and 1.6 (P < .07), respectively, compared with patients with low disease severity. (B) Classification of primary care utilization by disease severity. We assumed that patients with very high disease severity would receive at least 1 primary care visit a month, while patients with low disease severity would have at least 1 visit every 2 months. This corresponded to the lower quintile of average monthly visits within each disease severity category and was classified as infrequent primary care.

RESULTS

The majority of the study patients were white (91%), and approximately half of the cohort (46%) was between 30 and 39 years of age at study entry (Table 1). After controlling for severity of illness and period of care, patients of the least and moderately experienced physicians were half as likely to receive a primary care visit in a given month than patients cared for by the most experienced physicians (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.50, P = .002; OR 0.54, P < .001, respectively; Table 2). The odds of having a primary care visit were also significantly higher among patients with CD4 cell count <50/mm3 (OR 2.21, P < .001) and during the period immediately after the diagnosis of clinical AIDS compared with the interim period of care (OR 2.21, P < .001). Patients cared for by physicians with moderate and the most experience were significantly more likely to receive a specialty care visit compared with patients of the least experienced physicians (OR 1.79, P = .02; OR 1.66, P = .04, respectively). Specialty care included consultation with physicians specializing in infectious diseases, hematology/oncology, gastroenterology, and pulmonology.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Patient (N = 197)

| Characteristics | n (%)* |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, y | |

| 18–29 | 13 (7) |

| 30–39 | 91 (46) |

| 40–49 | 65 (33) |

| ≥50 | 28 (14) |

| Race or ethnic group | |

| White | 180 (91) |

| Black | 12 (6) |

| Hispanic | 4 (2) |

| Asian | 1 (1) |

| CD4 cell count category | |

| ≥200/mm3 | 42 (21) |

| 100–199/mm3 | 43 (22) |

| 50–99/mm3 | 36 (18) |

| 0–49/mm3 | 76 (39) |

| AIDS-defining illness | |

| P. carinii pneumonia | 63 (32) |

| Other opportunistic infections | 81 (41) |

| Kaposi's sarcoma | 20 (10) |

| Cytomegalovirus or herpes simplex virus | 16 (8) |

| Neurological disease | 15 (8) |

| Lymphoma | 2 (1) |

Because of rounding, percentages may not add to 100.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) of Medical Service Utilization in a Given Month According to Selected Variables (N = 197)

| Utilization Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Primary Care Visit | Specialty Care Visit | Hospitalization | Home Health/Hospice Visit | No Outpatient or Inpatient Visit |

| CD4 cell count | |||||

| ≥200/mm3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 100–199/mm3 | 1.45 (0.94 to 2.26) | 2.10 (1.33 to 3.32)† | 1.73 (0.95 to 3.12) | 2.32 (1.12 to 4.81)‡ | 0.51 (0.32 to 0.83)† |

| 50–99/mm3 | 1.35 (0.88 to 2.06) | 2.09 (1.33 to 3.29)§ | 2.84 (1.54 to 5.24)§ | 2.54 (1.11 to 5.78)‡ | 0.66 (0.4 to 1.09) |

| 0–49/mm3 | 2.21 (1.49 to 3.27)§ | 2.86 (1.91 to 4.27)§ | 2.95 (1.67 to 5.19)§ | 4.14 (2.06 to 8.34)§ | 0.31 (0.19 to 0.5)§ |

| Severity of AIDS-defining illness | |||||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 0.92 (0.65 to 1.29) | 1.30 (0.92 to 1.86) | 1.35 (0.94 to 1.94) | 1.38 (0.82 to 2.33) | 0.93 (0.62 to 1.38) |

| High | 0.91 (0.62 to 1.33) | 1.43 (0.94 to 2.18) | 1.10 (0.70 to 1.71) | 2.52 (1.41 to 4.51)† | 0.87 (0.53 to 1.42) |

| Months since AIDS diagnosis | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.01) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.04)§ | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.05)§ | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.01) |

| Period of care | |||||

| Diagnosis period | 2.21 (1.74 to 2.80)§ | 1.42 (1.11 to 1.83)† | 2.67 (1.86 to 3.83)§ | 1.16 (0.84 to 1.59) | 0.35 (0.26 to 0.46)§ |

| Interim period | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| End-of-life period | 0.60 (0.47 to 0.77)§ | 0.90 (0.68 to 1.18) | 6.51 (4.56 to 9.28)§ | 3.12 (2.33 to 4.18)§ | 0.63 (0.47 to 0.85)† |

| Physician experience level | |||||

| Least | 0.50 (0.32 to 0.77)† | 1.00‖ | 0.53 (0.32 to 0.88)‡ | 0.67 (0.33 to 1.38) | 2.46 (1.44 to 4.21)§ |

| Moderate | 0.54 (0.39 to 0.74)§ | 1.79 (1.09 to 2.93)‡ | 0.69 (0.48 to 0.99)‡ | 0.93 (0.57 to 1.53) | 1.81 (1.22 to 2.68)† |

| Most | 1.00 | 1.66 (1.04 to 2.65)‡ | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Odds ratios (ORs) were adjusted for all the other variables in the table.

Denotes P < .01.

Denotes P < .05

Denotes P < .001.

Reference category depicts the observed difference between moderate and most versus least experienced physicians.

CI, confidence interval.

Patients of physicians with the least and moderate experience had lower odds of hospitalization in a given month than patients of the most experienced physicians (OR 0.53, P = .01; OR 0.69, P = .04, respectively). There were no significant differences in length of hospital stay by physician experience level (data not shown). As expected, factors associated with higher odds of a patient receiving a hospice/home health visit included CD4 cell count <50/mm3 (OR 4.14, P < .001), high severity of AIDS-defining illness (OR 2.52, P = .002), increasing number of months since the diagnosis of AIDS (OR 1.04, P < .001), and the end-of-life period of care (OR 3.12, P < .001).

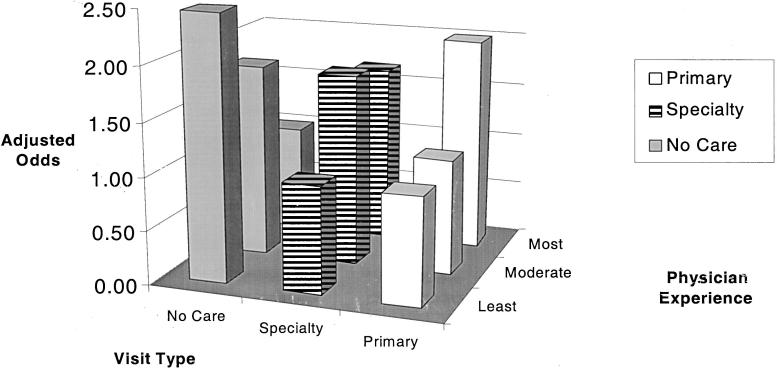

After controlling for other factors, patients of the least and moderately experienced physicians were significantly more likely to receive no primary or specialty care visits or hospitalizations in a given month compared with patients of the most experienced physicians (OR 2.46, P < .001; OR 1.81, P = .003, respectively; Fig. 2). The average frequency of outpatient visits among patients cared for by the most experienced physicians (1.67 visits per month) was similar to the frequency observed among a national sample of HIV-infected patients during the same time period (1.73 visits per month).6 Patients of the least experienced physicians received the lowest levels of pharmacy and laboratory services, while patients of moderately experienced physicians received the highest levels of ancillary services (P < .001; Table 3). Emergency room visits and long-term residential care were too infrequent to estimate the odds of delivery of these services among the study cohort.

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted odds ratio of primary care, specialty care, and no outpatient or inpatient care in a month according to physician experience level.

Table 3.

Mean Monthly Cost (Standardized to 1999 Dollars) of Medical Services per Patient by Physician Experience Level (N = 197)

| Physician Experience Level Mean $/Mo (95 % CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Service* | Least | Moderate | Most |

| Laboratory† | 29 (25 to 32) | 38 (34 to 43) | 35 (32 to 37) |

| Radiology† | 61 (36 to 95) | 78 (58 to 102) | 47 (38 to 58) |

| Pharmacy‡ | 166 (148 to 186) | 274 (253 to 294) | 265 (251 to 283) |

| Total‡ | 256 (218 to 296) | 390 (361 to 421) | 347 (326 to 371) |

P values are reported for all pair-wise comparisons between physician experience levels within each category of service.

Denotes P < .01.

Denotes P < .001.

CI, confidence interval.

Patients of the most experienced physicians had a median survival of 26.1 months from the time of clinical AIDS diagnosis, compared with 17.0 months for patients of moderately experienced physicians and 16.5 months for patients cared for by the least experienced physicians (P = .02). After controlling for disease severity, patients of the most experienced physicians who received infrequent primary care visits had a substantially lower risk of death than patients under their care who had more frequent primary care visits (HR = 0.15, P = .06; Table 5). There was a similar trend among patients who received infrequent primary care visits by moderately experienced physicians (HR = 0.66, P = .37), but no decrease in the risk of death among patients receiving infrequent care by the least experienced physicians (HR = 1.22, P = .72). Patients of the least experienced physicians who received infrequent primary care visits were 15.3 times more likely to die compared with patients who received the same level of care by the most experienced physicians (P = .02), and patients who received infrequent primary care by moderately experienced physicians were 6.9 times more likely to die than patients of the most experienced physicians (P = .08). Among patients receiving more frequent primary continuity care, those cared for by the least experienced physicians were 1.9 times more likely to die than patients of the most experienced physicians (P = .04), and patients of moderately experienced physicians had 1.6 times the risk of death (P = .06; Table 5). The rate of primary care visits and physician experience level were independent of severity of AIDS-defining diagnosis and CD4 cell count level in bivariate analyses. Specialty care, laboratory, radiology, and pharmacy utilization were not associated with survival among our study cohort after adjusting for other factors. Controlling for calendar time period and increasing physician experience level during the care of an individual patient did not affect the results (data not shown).

Table 5.

Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Death Physicians' Experience and Medical Service Utilization (N = 179)

| Physician Experience Level | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|

| The effect of infrequent vs more-frequent primary care visits within physician experience level | Least | 1.22 (0.40 to 3.77) |

| Moderate | 0.65 (0.26 to 1.64) | |

| Most | 0.15 (0.02 to 1.09)† | |

| The effect of physician experience among patients who received infrequent primary care | Least | 15.34 (1.67 to 140.79)‡ |

| Moderate | 6.90 (0.82 to 58.43)§ | |

| Most | 1.00 | |

| The effect of physician experience among patients who received more-frequent primary care | Least | 1.88 (1.03 to 3.41)‡ |

| Moderate | 1.57 (0.99 to 2.51)† | |

| Most | 1.00 |

Hazard ratios were adjusted for 1) disease severity at time of the diagnosis of AIDS measured by i) CD4 cell count and ii) severity of AIDS-defining illness; 2) time-varying hospital/hospice utilization measuring increased severity during the sudy period; 3) physician experience level; 4) time-varying primary care visit utilization classified as infrequent or more frequent; and 5) interactions terms for physician experience level and visit frequency.

P = .06.

Denotes P < .05.

Denotes P = .08.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

In 1996, prior to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the total number of HIV-infected patients cared for in the study setting was 519. In 1999, after HAART was in general use in the study setting, 493 HIV-infected patients were in care. Examination of medical services provided to the total population of HIV-infected patients demonstrated a significant increase in the volume and intensity (mean monthly cost per patient) of primary care visits provided in 1999 compared with 1996, while the level of laboratory, radiology, pharmacy services (excluding antiretroviral medications), and hospital and home health/hospice care remained stable or declined between the 2 time periods (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean Monthly Cost (Standardized to 1999 Dollars) of Medical Services per Patient by Calendar Period

| Medical Service | 1996 (N = 519) Mean $/Mo | 1999 (N = 493) Mean $/Mo | Change (1996 to 1999) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | 378 | 587 | +209 |

| Specialty care | 139 | 202 | +63 |

| Laboratory | 59 | 68 | +9 |

| Radiology | 42 | 21 | −21 |

| Pharmacy (non-antiretroviral) | 125 | 77 | −48 |

| Hospital and home health/hospice care | 235 | 40 | −195 |

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to determine whether patterns of medical care delivery by physicians with greater AIDS experience led to better outcomes among their patients. We found that patients of the most experienced physicians received twice the volume of ambulatory services including more frequent primary care visits and survived almost a year longer than patients of the least experienced physicians controlling for other factors. Closer outpatient follow-up by more experienced physicians provided the opportunity to diagnose acute illnesses earlier when less severe and institute more timely treatments. In addition, higher use of laboratory and pharmacy services meant that more experienced physicians could provide better monitoring of patients' stage of disease, leading to earlier screening for HIV-related conditions and interventions with prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, both of which lead to better outcomes.

Patients of moderately experienced physicians had less frequent primary care visits but received more specialty care and ancillary services; however, this delivery pattern did not result in a survival benefit. These findings suggest that physicians with moderate experience lacked the knowledge to make appropriate decisions independently and relied on frequent referrals to specialists. In this generalist-based delivery system, specialty expertise provided an essential counterpart to primary care but did not substitute for greater AIDS experience among primary care physicians. Our results demonstrate that primary care delivery to HIV-infected patients in the era of HAART has increased significantly compared with the time period immediately before the introduction of HAART, while the level of other services has remained stable or declined. Thus, primary care is playing an even greater role in patient care in the current treatment environment. For primary care physicians, the complexity of HIV care and, in particular, decision making in regard to antiretroviral treatment has increased dramatically. Physicians with greater HIV experience have been shown to provide more appropriate antiretroviral therapy and to adopt newer antiretroviral regimens earlier than less experienced physicians.44 Because treatment for HIV infection is rapidly advancing, repeated delays in adoption of new therapies by less experienced physicians may significantly affect patient outcomes. Thus, physicians' experience in the care of persons with HIV infection has an even greater effect on clinical outcomes in the HAART era. Our findings suggest that physicians with greater experience delivered more care to the patients who needed it and less to the patients who did not. After controlling for differences in utilization of services, an effect of physician experience level on survival remained. Therefore, in addition to providing more appropriate levels of care, physicians with greater experience delivered care more effectively.

The relation between utilization, physician experience level, and survival is complex. We addressed potential differences in case mix by adjusting for disease severity using several categorical measures including severity of AIDS-defining illness and CD4 cell count level. However, there are probably unmeasured differences in severity of illness within each category that confound the effect of utilization on survival. Patients who received the lowest level of primary care visits probably included patients with low disease severity for whom infrequent care was appropriate, and some for whom more frequent follow-up was needed to address greater severity of illness. Among this group of patients, we found an effect of utilization on survival attributable to failure of less experienced physicians to provide appropriate levels of care. We also found an effect of utilization on survival that varied by physician experience level among patients receiving higher frequency of primary care visits, probably due to most experienced physicians providing care more effectively to patients with higher disease severity.

We demonstrated by several methods that selective referral45 did not contribute to the effect of physician experience level.1 Furthermore, because we examined the changing performance of physicians as they went from treating a low volume of patients to treating a higher volume of patients, our results provide evidence for a causal direction in the volume–outcome relationship,46 namely, that experience gained in caring for more patients leads to better outcomes. This study complements previous research on the relation between hospital service utilization and in-hospital mortality28–32 by defining patterns of longitudinal services delivered to a cohort of patients throughout the course of disease that result in better long-term survival. We found no association between patients cared for by the same physician and their visit frequency and thus observed no systematic effect of patients on visit frequency that could have biased these results. Our findings may be specific to men who have male sexual contact as a risk factor for HIV transmission and who receive care in a generalist-based HMO.

This study demonstrates the importance of appropriate utilization of services among primary care physicians managing patients with AIDS. Continuing medical education is the most common approach to improving expertise of generalist providers but has been shown to have no lasting effect on practice.47 Conventional referral or consultation remains the dominant source of expert assistance in managed care as well as fee-for-service practice.8 For a primary care physician, gaining experience may involve acquiring information through consultation with specialists and interacting effectively with consultants. However, some managed care plans limit specialty consultation as a way of controlling costs.48 Our findings suggest that generalist physicians with the most experience in the care of persons with AIDS achieved better outcomes by providing appropriate primary continuity care and benefited from ongoing collaboration with specialists. It is essential that health plans ensure access to physicians possessing the HIV experience necessary to define appropriate medical resource use.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to the memory of our colleague, G. Eric Archibeque, MD (September 15, 1958–September 11, 1999), who inspired all who knew him to reach higher to improve the care of persons living with HIV infection.

This work was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kitahata M, Koepsell T, Deyo R, Maxwell C, Dodge W, Wagner E. Physicians' experience with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome as a factor in patients' survival. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:701–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham N, Zeger S, Park L, et al. The effects on survival of early treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1037–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204163261601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osmond D, Charlebois E, Lang W, Shiboski S, Moss A. Changes in AIDS survival time in two San Francisco cohorts of homosexual men, 1983 to 1993. JAMA. 1994;271:1083–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly J, Chu S, Buehler J. AIDS deaths shift from hospital to home. AIDS Mortality Project Group. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1433–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.10.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellinger F. Forecasts of the costs of medical care for persons with HIV: 1992–1995. Inquiry. 1992;29:356–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellinger F. The lifetime cost of treating a person with HIV infection. JAMA. 1993;270:474–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. Longitudinality and managed care; pp. 41–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner E, Austin B, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Korff M Von. Improving outcomes in chronic illness. Manag Care Q. 1996;4:12–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korff M Von, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1097–102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wasson J, Sauvigne A, Mogielnicaki R, et al. Continuity of outpatient medical care in elderly men. A randomized trial. JAMA. 1984;252:2413–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stason W, Shepard D, Perry H, Jr, et al. Effectiveness and costs of Veterans Affairs hypertension clinics. Med Care. 1994;32:1197–215. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diabetes Complications and Control Trial Research G. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complication in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program: I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA. 1979;242:2562–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shultz J, Sheps S. Management of patients with hypertension: a hypertension clinic model. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:997–9. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61829-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katon W, Robinson P, Korff M Von, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:924–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100072009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katon W, Korff M Von, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leveille SG, Wagner EH, Davis C, et al. Preventing disability and managing chronic illness in frail older adults: a randomized trial of a community-based partnership with primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1191–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCulloch D, Price M, Hindmarsh M, Wagner E. A population-based approach to diabetes management in a primary care setting: early results and lessons learned. Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1:12–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCulloch D, Price M, Hindmarsh M, Wagner E. Improvement in diabetes care using an integrated population-based approach in a primary care setting. Dis Management. 2000;3:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seage G, Landers S, Barry A, Groopman J, Lamb G, Epstein A. Medical care costs of AIDS in Massachusetts. JAMA. 1986;256:3107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrulis D, Beers V, Bentley J, Gage L. The provision and financing of medical care for AIDS patients in US public and private teaching hospitals. JAMA. 1987;258:1343–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrulis D, Weslowski V, Gage L. The 1987 US hospital AIDS survey. JAMA. 1989;262:784–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett C, Cvitanic M, Pascal A. The costs of AIDS in Los Angeles. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett C, Pascal A, Cvitanic M, Graham V, Kitchens A, DeHovitz JA. Medical care costs of intravenous drug users with AIDS in Brooklyn. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bozzette S, Berry S, Duan N, et al. The care of HIV-infected adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1897–904. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett C, Garfinkle J, Greenfield S, et al. The relation between hospital experience and in-hospital mortality for patients with AIDS-related PCP. JAMA. 1989;261:2975–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stone V, Seage G, III, Hertz T, Epstein A. The relation between hospital experience and mortality for patients with AIDS. JAMA. 1992;268:2655–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett C, Adams J, Gertler P, et al. Relation between hospital experience and in-hospital mortality for patients with AIDS-related Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: experience from 3,126 cases in New York City in 1987. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:856–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wachter R, Luce J, Safrin S, Berrios D, Charlebois E, Scitovsky A. Cost and outcome of intensive care for patients with AIDS, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, and severe respiratory failure. JAMA. 1995;273:230–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horner R, Bennett C, Achenbach C, et al. Predictors of resource utilization for hospitalized patients with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP): a summary of effects from the multi-city study of quality of PCP care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;12:379–85. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199608010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heagerty P, Zeger S. Lorelogram: a regression approach to exploring dependence in longitudinal categorical responses. J Am Stat Assoc. 1998;93:150–62. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang K, Zeger S. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hellinger F, Fleishman J, Hsia D. AIDS treatment costs during the last months of life: evidence from the ACSUS. Health Serv Res. 1994;29:569–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scitovsky A, Cline M, Lee P. Medical care costs of patients with AIDS in San Francisco. JAMA. 1986;256:3103–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solomon D, Hogan A. HIV infection treatment costs under Medicaid in Michigan. Public Health Rep. 1992;107:461–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner B, Markson L, McKee L, Houchens R, Fanning T. The AIDS-defining diagnosis and subsequent complications: a survival-based severity index. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:1059–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cox D. Regression models and life-tables. J Royal Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalbfleisch J, Prentice R. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York: Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shapiro MF, Morton SC, McCaffrey DF, et al. Variations in the care of HIV-infected adults in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. JAMA. 1999;281:2305–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.24.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kitahata M, Van Rompaey S, Shields A. Physicians' experience in the care of HIV-infected persons is associated with earlier adoption of new antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:106–14. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luft HS, Hunt SS, Maerki SC. The volume-outcome relationship: practice-makes-perfect or selective- referral patterns? Health Serv Res. 1987;22:157–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hannan EL. The relation between volume and outcome in health care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1677–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905273402112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis D, Thomson M, Oxman A, Haynes R. Evidence for the effectiveness of CME. A review of 50 randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1992;268:1111–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kitahata M, Holmes K, Wagner E, Gooding T. Caring for persons with HIV infection in a managed care environment. Am J Med. 1998;104:511–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]