Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To develop a meta-analysis to determine the effectiveness of rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

DATA SOURCES

medline, cinhal, and Cochrane Library searches for trials of rehabilitation for COPD patients. Abstracts presented at national meetings and the reference lists of pertinent articles were reviewed.

STUDY SELECTION

Studies were included if: trials were randomized; patients were symptomatic with forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) <70% or FEV1 divided by forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) <70% predicted; rehabilitation group received at least 4 weeks of rehabilitation; control group received no rehabilitation; and outcome measures included exercise capacity or shortness of breath. We identified 69 trials, of which 20 trials were included in the final analysis.

DATA EXTRACTION

Effect of rehabilitation was calculated as the standardized effect size (ES) using random effects estimation techniques.

RESULTS

The rehabilitation groups of 20 trials (979 patients) did significantly better than control groups on walking test (ES = 0.71; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.43 to 0.99). The rehabilitation groups of 12 trials (723 patients) that used the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire had less shortness of breath than did the control groups (ES = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.89). Trials that used respiratory muscle training only showed no significant difference between rehabilitation and control groups, whereas trials that used at least lower-extremity training showed that rehabilitation groups did significantly better than control groups on walking test and shortness of breath. Trials that included severe COPD patients showed that rehabilitation groups did significantly better than control groups only when the rehabilitation programs were 6 months or longer. Trials that included mild/moderate COPD patients showed that rehabilitation groups did significantly better than control groups with both short- and long-term rehabilitation programs.

CONCLUSION

COPD patients who receive rehabilitation have a better exercise capacity and they experience less shortness of breath than patients who do not receive rehabilitation. COPD patients may benefit from rehabilitation programs that include at least lower-extremity training. Patients with mild/moderate COPD benefit from short- and long-term rehabilitation, whereas patients with severe COPD may benefit from rehabilitation programs of at least 6 months.

Keywords: rehabilitation, obstructive lung disease, shortness of breath, exercise, review

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States.1,2 It is a debilitating lung disease that affects 14 million persons, and it is the fourth leading cause of death.3 In addition to smoking cessation and medical treatment, the American Thoracic Society (ATS)3 and the Department of Veterans' Affairs (VA)4 guidelines recommend rehabilitation for COPD patients with continued respiratory symptoms despite medical treatment and for patients with limited functional capacity. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves quality of life and exercise capacity in clinically stable patients with COPD.5

Although rehabilitation has been shown to improve exercise capacity, its effect on subgroups of COPD patients is still not well characterized. According to the American Thoracic Society Guidelines, there is a wide variation in rehabilitation regimens and there is a need for new studies to establish an optimal guideline for rehabilitation.3

The aim of this study is to develop a meta-analysis to assess the effect of rehabilitation on exercise capacity and shortness of breath in patients with COPD, and to determine the optimal type and duration of rehabilitation programs.

METHODS

Data Sources

The primary search included medline (1966 to September 2000), cinhal (1990 to September 2000), and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register for trials published in all languages. The terms used in the search were: lung disease, obstructive;COPD;rehabilitation; exercise; and training. The search was then limited to randomized controlled trials. To identify unpublished data, we reviewed abstracts presented at national meetings (American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society) and reviewed the reference lists of pertinent articles.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included trials if they were randomized controlled and included patients with obstructive lung disease defined as either forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) <70% predicted value or FEV1 divided by forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) <70% predicted value. Trials that included patients with asthma and trials with no FEV1 documentation were excluded. Patients in the included trials had to either be symptomatic or have evidence of impaired exercise capacity. We included trials that used any type of rehabilitation (upper-extremity, lower-extremity, or respiratory muscle exercise) 3 times a week for at least 4 weeks. Only trials that reported outcome measures of exercise capacity and shortness of breath were included. If a trial included more than 1 rehabilitation group, we included only the most comprehensive group and the control group. Inter-rater agreements on trial inclusion were assessed by the κ value.

Quality Assessment

Two investigators assessed the methodological quality of the included trials. Using published literature on quality assessment,6,7 we used a 4-point scale to assign a quality score for each trial. The quality score included 4 criteria1: all patients who entered the trial were properly accounted for at its conclusion2; investigators who did the assessment were blinded to treatment assignment3; groups were similar at the start of the trial; and4 patients were treated equally. Inter-rater agreement quality scores were assessed by the κ value.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures included the effect of rehabilitation on exercise capacity measured by the walking test, and the effect of rehabilitation on shortness of breath measured by the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRDQ).

We performed a meta-regression to explore potential association between the outcome measures and characteristics of rehabilitation or patient population.8 The dependent variables were walking distance and shortness of breath, and the independent variables were severity of COPD, type of rehabilitation, and duration of the rehabilitation.

Statistical Analysis

Effect Size

We calculated the treatment effects for each individual trial as the mean difference in the change from baseline scores between intervention and control groups. To accommodate differing units of measurement among the trials, we calculated the effect size (ES) by dividing the treatment effect of each trial by the combined standard deviation of the change in the intervention and control groups of the same trial. The individual standardized effect sizes were combined using the random-effect approach of Der-Simonian and Laird.9 The random-effect approach assumes that the observed ES from each trial is a random sample from a larger population of possible effect sizes, and that there is random variation among the effect sizes in the population as opposed to one fixed true ES. Thus, the total variance of an estimated ES reflects both the estimation variability and the population random effects variance. The combined ES and confidence limits computed using this technique are therefore more conservative than a fixed-effect estimate.9

Sensitivity Analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the results to different assumptions.8 These included checking for differences in the ES estimates resulting from the methodological quality of the trials, the statistical method of calculating ES, and the presence of publication bias. Publication bias was examined by stratifying the analyses by trial size. Larger trials can detect smaller effects as statistically significant. If publication bias is present, it is expected that the larger studies will report small effect sizes, whereas small studies will report large effect sizes.

We also checked the robustness of the pooled ES to removal of the trials with the largest effect sizes. We ranked the trials by the value of their individual effect sizes, then eliminated, one at a time, the trials with the highest ranks. Then we assessed the significance of the pooled effect of the remaining trials. We repeated this process until the pooled ES was no longer significant.10

Test of Heterogeneity

We examined the consistency of treatment effect across the primary trials. Some divergence of trial results from the overall estimate is always expected purely by chance. If the test of heterogeneity is statistically significant (P < .05), the between-trial variability is more than that expected by chance alone. Consistency of trial results despite variation in trial characteristics provides important and powerful corroboration of the generalization of the treatment effect.8

RESULTS

The search of medline, cinhal, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register resulted in 456 randomized controlled trials about rehabilitation for patients with obstructive lung disease (Fig. 1). Of these, 407 trials were excluded after initial review. Twenty trials were added after searching the reference lists of the 49 relevant articles and abstracts from national meetings. Thus, a total of 69 trials were considered for inclusion. Two reviewers evaluated these trials for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Both agreed to include 18 trials and exclude 49 trials. They disagreed on 8 trials, 2 of which were included after consultation with a third reviewer. A total of 20 (999 patients) trials were included in the final analysis. The percent agreement between the 2 reviewers was 91%, with a κ value of 0.79.

FIGURE 1.

Identification and selection of trials. ICU, intensive care unit; SOB, shortness of breath; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Twenty trials11–29 (979 patients) used the walking test to assess exercise capacity. Twelve trials14–17,20,23,25,27–30 (723 patients) used the CRDQ to assess shortness of breath. (One published study [27] was considered as 2 trials because it included 2 intervention groups and 2 control groups.) Fifteen trials included mild to moderate COPD patients with average FEV1 values >35%, or 0.8 L (Table 1). Six trials included severe COPD patients with average FEV1 values ≤35%, or 0.8 L (Table 2 There were no significant differences between the number of patients who dropped out of the rehabilitation groups and the number of patients who dropped out of the control groups (t test; P = .639).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Trials With Mild/Moderate COPD Patients

| Author | Patients, n | FEV1 %, or Liters (SD) | Age in Years (SD) | Duration | Intervention* | Baseline Walking Distance in Meters (SD)† | Baseline Shortness of Breath by CRDQ (SD) | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lake FR11 | 14 | 0.9 L (0.25) | 66 (2) | 8 wk | U and L | C 355 (72) | 3 | |

| T 327 (103) | ||||||||

| Gosselink R13 | 19 | 43% (15) | NA | 3 mo | U and L | C −0.1 (16)‡ | 2 | |

| T 15.9 (27)‡ | ||||||||

| Wijkstra PJ15 | 36 | 1.2 L (0.3) | 62.1 (5) | 12 wk | U, L, and R | C 462 (34) | C 70 (3) | 2 |

| T 460 (35) | T 76 (5) | |||||||

| Simpson K16 | 28 | 39.4% (20) | 71 (5) | 8 wk | U and L | C 506 (86) | C 15.6 (1.3) | 2 |

| T 518 (69) | T 13.3 (1.3) | |||||||

| Guyatt G17 | 82 | 1.0 L (0.34) | 66 (7.5) | 6 mo | R | C 409 (94) | C 33.2 | 3 |

| T 406 (86) | T 35.4 | |||||||

| Strijbos JH18 | 30 | 42% (14) | 61 (5.3) | 3 mo | L | C 262 (12) | 2 | |

| T 280 (14) | ||||||||

| McGavin C19 | 24 | 1.05 L (0.50) | 59 (6.8) | 3 mo | L | C 509 (156) | 2 | |

| T 526 (66) | ||||||||

| Cambach W20 | 19 | 60%(19) | 62 (7) | 3 mo | U, L, and R | C 494 (78) | C 19 (4) | 2 |

| T 480 (99) | T 19 (4) | |||||||

| Cockcroft A21 | 34 | 1.42 L (0.6) | 61 (4.9) | 7 mo | U and L | C 564 (221) | 4 | |

| T 523 (296) | ||||||||

| Bendstrup K23 | 32 | 1.03 L (0.02) | 64 (2) | 12 wk | U and L | C 36.1 (10)‡ | C 0.6 (3.8)‡ | 3 |

| T 113.1 (18)‡ | T 8.6 (3.5)‡ | |||||||

| Sassi-Dambron D24 | 77 | 1.15 L (0.6) | 67.4 (8) | 6 wk | R | C 397 (114) | 2 | |

| T 402 (75) | ||||||||

| Griffith TL25 | 200 | 39.5%(16.3) | 68.2 (8.1) | 6 wk | U and L | C 125 (97) | C 12.8 (5.0) | 2 |

| T 140 (94) | T 13.9 (3.8) | |||||||

| Wedzicha J27 | 56 | 0.98 L (0.3) | 68.6 (7.7) | 8 wk | U and L | C 217 (22) | C 82 (22) | 2 |

| T 191 (22) | T 82 (18) | |||||||

| Troosters T29 | 62 | 42% (8) | 61 (8) | 6 mo | U and L | C 61 (18) | C 84 (22) | 2 |

| T 60 (19) | T 77 (17) | |||||||

| Bauldoff GS30 | 20 | 50%(22) | 62 (14) | 8 wk | U | C 14.8 (5) | 1 | |

| T 17.1 (2.6) |

R, respiratory muscle rehabilitation; U, upper-extremity rehabilitation; L, lower-extremity rehabilitation.

T, treatment group; C, control group.

The difference between values at the completion of trial and starting values.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume at 1 second; CRDQ, Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Studies With Severe COPD Patients

| Primary Author | Patients, n | FEV1%, or Liters (SD) | Age in Years (SD) | Duration | Intervention* | Baseline Walking Distance in Meters (SD)† | Baseline Shortness of Breath by CRDQ (SD | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weiner P12 | 24 | 35% (2.7) | 65 (2.8) | 6 mo | U, L, and R | C 627 (96) | 3 | |

| T 611 (88) | ||||||||

| Goldstein R14 | 77 | 34.7%(13) | 66 (7) | 6 mo | U, L, and R | T − C = 37.8‡ | T − C= 3.0‡ | 2 |

| Jones DT22 | 14 | 0.74 L (20) | 63 (7.2) | 10 wk | U and L | C 869 (62) | 2 | |

| T 855 (155) | ||||||||

| Engstrom C26 | 50 | 32.4% (10.8) | 66.4 (5.4) | 12 mo | U, L, and R | C 308 (15) | 2 | |

| T 312 (14) | ||||||||

| Wedzicha J27 | 54 | 0.80 L (0.34) | 72.5 (6) | 8 wk | U and L | C 75 (11) | C 75 (22) | 2 |

| T 108 (15) | T 74 (21) | |||||||

| Guell R28 | 47 | 35% (13) | 64 (7) | 6 mo | R and L | C 296 (56) | C 3.3 (1) | 2 |

| T 315 (61) | T 3.1 (1) |

R, respiratory muscle rehabilitation; U, upper-extremity rehabilitation; L, lower-extremity rehabilitation.

T, treatment group; C, control group.

The difference between values at the completion of trial and starting values.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume at 1 second; CRDQ, Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire.

The two reviewers evaluated the methodological quality of the 20 trials included in the final analysis (Tables 1,Tables 2). The percent agreement on the quality score was 79% with a κ value of 0.55.

Pooled Analysis

Walking Test

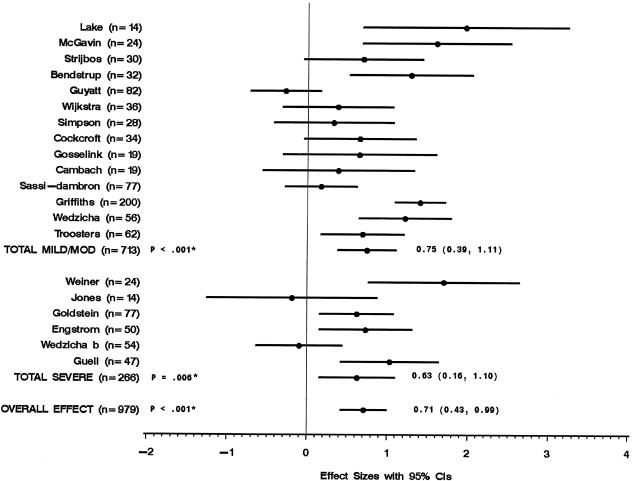

Figure 2 shows the twenty trials (979 patients) that used the walking test to evaluate the effect of rehabilitation on walking distance. Pooled analysis showed that the rehabilitation groups did significantly better than control groups on the walking test. Subgroup analyses showed that the rehabilitation groups of trials that included mild/moderate COPD patients and trials that included severe COPD patients did significantly better than control groups. The results of the twenty trials and the subgroups were heterogeneous.

FIGURE 2.

Walking distance measured by effect size of each trial. * P values for test of heterogeneity.

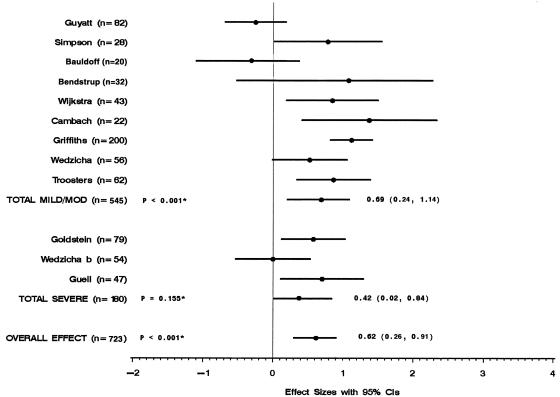

Shortness of Breath

Figure 3 shows the results of the 12 trials (723 patients) that used the CRDQ to evaluate the effect of rehabilitation on shortness of breath. Pooled analysis showed that the rehabilitation groups were significantly less short of breath than were control groups. Subgroup analyses showed that the rehabilitation groups of trials that included mild/moderate COPD patients and trials that included severe COPD patients were both significantly less short of breath than were control groups. The results of the 12 trials and trials that included mild/moderate COPD patients were heterogeneous, whereas the results of 3 trials that included severe COPD patients were homogeneous.

FIGURE 3.

Shortness of breath measured by effect size of each trial. * P values for test of heterogeneity.

Meta-regression

The purpose of the meta-regression was to examine gradients in treatment effects and to explore potential association between the outcome measures and characteristics of rehabilitation or patient population. We checked the effect of variations in the severity of COPD, type of rehabilitation, or duration of the rehabilitation program on walking distance and shortness of breath.

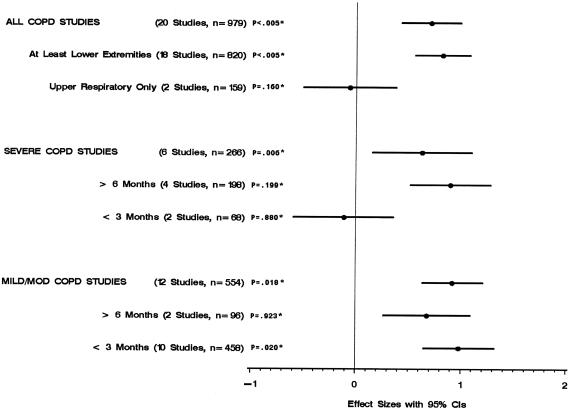

Walking Test

Figure 4 shows that the rehabilitation groups in the trials that included at least lower-extremity training (18 trials) did significantly better than control groups on the walking test. In the trials that included respiratory muscle training only, there was no significant difference between rehabilitation and control groups. In the trials that included severe COPD patients, the rehabilitation groups did significantly better than control groups only when the rehabilitation programs were 6 months or longer. On the other hand, the rehabilitation groups of the trials that included patients with mild/moderate COPD did significantly better than control groups with both long- and short-term rehabilitation programs.

FIGURE 4.

Walking distance by study characteristics. * P values for test of heterogeneity.

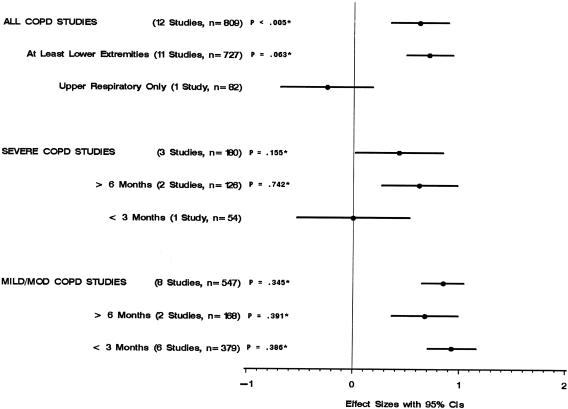

Shortness of Breath

Figure 5 shows that the rehabilitation groups in the trials that included at least lower-extremity training (11 trials) were significantly less short of breath than were the control groups. One trial that included respiratory muscle training only showed that there was no significant difference in shortness of breath between rehabilitation and control groups. In trials that included severe COPD, the rehabilitation groups experienced less shortness of breath than did control groups only when the rehabilitation programs were 6 months or longer. On the other hand, the rehabilitation groups of the trials that included patients with mild/moderate COPD were less short of breath than were control groups in both long- and short-term rehabilitation programs.

FIGURE 5.

Shortness of breath by study characteristics. * P values for test of heterogeneity.

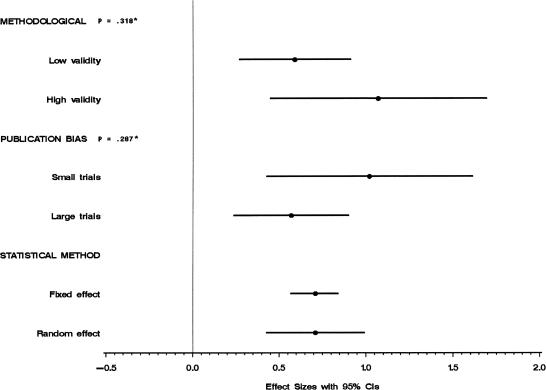

Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis is illustrated in Figure 6. First, there was no significant difference between the trials with methodological quality score of 2 or less (low validity) and trials with methodological quality score of 3 or more (high validity). Second, assessment of publication bias showed that trials with subjects less than 25 patients have larger treatment effect sizes. This is a sign of publication bias. However, exclusion of these trials has no significant effect on the overall ES. We also checked for publication bias by using the statistical test developed by Begg.31 Results showed no significant publication bias with P = .2428. Third, there was no significant difference between the overall ES when calculated using the random-effects method and the overall ES when calculated using the fixed-effects method. The confidence interval is slightly wider when using the random-effects method.

FIGURE 6.

Sensitivity analysis. *P values for test of heterogeneity.

We also evaluated the strength of the meta-analysis results by checking the robustness of the pooled ES after removing trials with the largest effect sizes. The more trials that can be removed before the pooled ES becomes nonsignificant, the more robust the meta-analysis. The pooled ES for the walking test became nonsignificant (P = .024) only after removal of 9 studies (509 patients).

DISCUSSION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for more than 110,000 deaths in 1998.32 COPD is responsible for more than $30 billion a year in direct medical care expenditures and indirect costs.33 Although 16 million cases of the disease have been diagnosed, an estimated 15 million cases or more remain undiagnosed.34 The quality of life for a person suffering from COPD diminishes as the disease progresses. A recent American Lung Association (ALA) survey revealed that half of all COPD patients (51%) say their condition limits their ability to work. It also limits them in normal physical exertion (70%), household chores (56%), social activities (53%), sleeping (50%), and family activities (46%).33

A previous meta-analysis by Lacasse et al.35 showed that rehabilitation for COPD patients improves exercise capacity and quality of life, including shortness of breath. Pulmonary rehabilitation also results in substantial savings in health care costs. A randomized controlled trial by Griffiths et al.36 showed that an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation program was cost-effective and was likely to result in financial benefit to the health service. Previous studies by Lertzman and Cherniak37 and Jensen38 also showed that pulmonary rehabilitation results in fewer hospitalizations and in decreased length of hospital stay.

The ATS and VA guidelines recommend rehabilitation for patients with continued respiratory symptoms despite medical treatment and for patients with limited functional capacity. According to an ALA survey,33 at least half of COPD patients have limitations in their activities of daily living. Thus, half of COPD patients are expected to benefit from rehabilitation. The ATS and VA guidelines do not specify the type or the duration of rehabilitation. Although rehabilitation for COPD patients is used by many medical centers to improve exercise capacity and decrease shortness of breath, the standards of care are still a subject of clinical judgment. A national survey of 150 programs showed wide variation in program delivery.39 The optimal frequency and length of such programs has not been determined.

The meta-analysis by Lacasse et al.35 showed an improvement in walking distance with an ES of 0.6 (0.3 to 1.0), which was equivalent to 55.7 meters (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 27.8 to 92.8). Our meta-analysis showed a comparable ES of 0.71 (95% CI, 90.43 to 0.99), which was equivalent to 50.57 meters (95% CI, 30.3 to 70.8). However, the meta-analysis by Lacasse et al.35 failed to identify factors that are associated with improvement in outcome.

One strength of this study resides in identifying the factors that are associated with improvement in outcome measures. Unlike respiratory muscle training, lower-extremity training was associated with beneficial outcome among rehabilitation groups irrespective of severity of illness of COPD patients. The other finding was that patients with severe COPD required rehabilitation programs of 6 months or longer for the rehabilitation group to show benefit over the control group. These findings conform with the physiologic changes after rehabilitation. Rehabilitation increases exercise tolerance by improving neuromuscular coordination and desensitizing dyspnea perception. This leads to improved ability to carry out everyday activities.40

Another strength of this study resides in the meta-regression's ability to explain the heterogeneity of the results. Because the trials were not conducted according to a common protocol, there were variations in patient groups, clinical settings, concomitant care, and methods of delivery of intervention. Heterogeneous results are less generalizable because of the possibility of hidden factors associated with the changes in the results. The meta-regression helped to explain the variation between subgroups, rendering the results of within-subgroups consistent. This provides a powerful corroboration of the generalization of the treatment effect, and it places a greater degree of certainty on the application of the findings to wider clinical practice.

The robustness of this meta-analysis to different methodological and validity assumptions adds to the strength of the results. Neither the variation in the way we calculated ES nor the variation in the validity of the trials had significant impact on the results of the meta-analysis. In addition, although there was a tendency toward a publication bias, it did not affect the results.

The limitations of our study include: First, we used aggregate data instead of individual patients' information. This may have underestimated or overestimated the outcome measures. Second, the meta-analysis included small-size trials with large effect sizes. This may have skewed the results toward a beneficial effect of rehabilitation groups. Third, the intervention could not be concealed and was classified as upper, lower, or respiratory training without details about each intervention.

Finally, future trials should include large numbers of patients, and they should be randomized controlled trials. In addition to exercise capacity and shortness of breath, outcomes should also include survival rate, hospitalization rate, and health care cost.

CONCLUSION

The results of this meta-analysis support the role of rehabilitation in the treatment of patients with COPD. Rehabilitation improves walking capacity and shortness of breath in patients with COPD. All patients with symptomatic COPD may benefit from rehabilitation programs that include at least lower-extremity training. Patients with severe COPD may benefit from rehabilitation for at least 6 months, while patients with mild to moderate COPD may benefit from shorter rehabilitation programs. These findings provide new insights into the effectiveness of rehabilitation for COPD patients, and may decrease variations in rehabilitation regimens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Petty TL. Definition, causes, course, and prognosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care Clin N Am. 1998;4:345–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keistinen T, Tuuponen T, Kivela SL. Survival experience of the population needing hospital treatment for asthma and COPD at age 50–54 years. Respir Med. 1998;92:568–72. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Thoracic Society. Pulmonary rehabilitation 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1666–82. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.ats2-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACCP/AACVPR Pulmonary Rehabilitation Guidelines Panel. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based guidelines. American College of Chest Physicians. American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Chest. 1997;112:1363–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casaburi R. Principles and Practice of Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1993. Exercise training in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; pp. 204–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Jadad AR, Nichol G, Penman M, Tugwell P, Walsh S. Assessing the quality of randomized clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1995;16:62–73. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(94)00031-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ. Users' Guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1993;270:2598–601. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.21.2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG. Systemic Reviews in Health Care. 2nd ed. London: BMJ Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Der-Simonian R, Laird NM. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montori VM, Smieja M, Guyatt GH. Publication bias: a brief review for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1284–88. doi: 10.4065/75.12.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lake RF, Henderson K, Briffa T, Openshaw J, Musk AW. Upper-limb and lower-limb exercise training in patients with chronic airflow obstruction. Chest. 1990;97:1077–82. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.5.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiner P, Azgad Y, Ganam R. Inspiratory muscle training combined with general exercise reconditioning in patients with COPD. Chest. 1992;102:1351–56. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.5.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gosselink R, Troosters T, Rollier H. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves exercise capacity in COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:976–80. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.3.8630582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein RS, Gort EH, Stubbing D, Avendano MA, Guyatt GH. Randomized controlled trial of respiratory rehabilitation. Lancet. 1994;344:1394–97. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90568-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wijkstra PJ, TenVergert EM, vanAltena RV, et al. Long term benefits of rehabilitation at home on quality of life and exercise tolerance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1995;50:824–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.8.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson K, Killian K, McCartney N, Stubbing DG, Jones NL. Randomized controlled trial of weightlifting exercise in patients with chronic airflow limitation. Thorax. 1992;47:70–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.2.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guyatt G, Keller J, Singer J, Halcrow S, Newhouse M. Controlled trial of respiratory muscle training in chronic airflow limitation. Thorax. 1992;47:598–602. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.8.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strijbos JH, Postma DS, vanAltena RV, Gimeno F, Koeter GH. A comparison between an outpatient hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation program and a home-care pulmonary rehabilitation program in patients with COPD. A follow-up of 18 months. Chest. 1996;109:366–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGavin CR, Gupta SP, Lloyd EL, McHardy GJ. Physical rehabilitation for the chronic bronchitic: results of a controlled trial of exercise in the home. Thorax. 1977;32:307–11. doi: 10.1136/thx.32.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cambach W, Chadwick RM, Wagenaar RC, van Keimpema AR, Kemper HC. The effects of a community pulmonary rehabilitation programme on exercise tolerance and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:104–13. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cockcroft AE, Saunders MJ, Berry G. Randomized controlled trial of rehabilitation in chronic respiratory disability. Thorax. 1981;36:200–3. doi: 10.1136/thx.36.3.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones DT, Thomson RJ, Sears MR. Physical exercise and resistive breathing training in severe chronic airway obstruction—are they effective? Eur J Respir Dis. 1985;67:159–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bendstrup KE, Ingemann JJ, Holm S, Bengtsson B. Out-patient rehabilitation improves activities of daily living, quality of life and exercise tolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:2801–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10122801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sassi-Dambron DE, Eakin EG, Ries AL, Kaplan RM. Treatment of dyspnea in COPD. A controlled clinical trial of dyspnea management strategies. Chest. 1995;107:724–29. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.3.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths TL, Burr ML, Campbell IA, et al. Results at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:362–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engstrom CP, Persson LO, Larson S, Sullivan M. Long-term effects of a pulmonary rehabilitation programme in outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1999;31:207–13. doi: 10.1080/003655099444371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wedzicha JA, Bestall JC, Garrod R, Garnham R, Paul EA, Jones PW. Randomized controlled trial of pulmonary rehabilitation in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients, stratified with the MRC dyspnoea scale. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:363–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guell R, Casan P, Belda J, et al. Long term effects of outpatient rehabilitation of COPD: a rondomized trial. Chest. 2000;117:976–83. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.4.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Troosters T, Gosselink R, Decramer M. Short- and long-term effects of outpatient rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Am J Med. 2000;109:207–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00472-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bauldoff GS, Hoffman LA, Sciurba F, Zullo TG. Home-based, upper-arm exercise training for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung. 1996;25:288–94. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(96)80064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Begg CB. Publication bias. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. The Handbook of Research Synthesis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. pp. 399–409. [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Data fact sheet chronic obstructive lung disease. March 24, 2002. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/lung/other/copd.pdf.

- 33.American Lung Association. Fact sheet: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. March 2002. Available at: http://www.lungusa.org/diseases/copd_factsheet.html. Accessed March 24, 2002.

- 34.Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1683–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lacasse Y, Wong E, Guyatt GH, King D, Cook DJ, Goldstein RS. Meta-analysis of respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 1996;348:1115–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffiths TL, Phillips CJ, Davies S, Burr ML, Campbell IA. Cost effectiveness of an outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation programme. Thorax. 2001;56:779–84. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.10.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lertzman MM, Cherniak RM. Rehabilitation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114:1145–65. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.114.6.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen PS. Risk, protective factors, and supportive interventions in chronic airway obstruction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1203–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100049007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bickford LS, Hodgkin JE. National pulmonary rehabilitation survey. Respir Care. 1988;33:1030–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pierce AK, Taylor HF, Archer RK, Miller WF. Responses to exercise training in patients with emphysema. Arch Intern Med. 1964;113:28–36. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1964.00280070030007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]