Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the impact of an intervention designed to help patients choose a new primary care provider (PCP) compared with the usual method of assigning patients to a new PCP.

DESIGN

Randomized controlled trial conducted between November 1998 and June 2000.

INTERVENTION

Provision of telephone or web-based provider-specific information to aid in the selection of a provider.

SETTING

Medical center within a large HMO.

PATIENTS

One thousand and ninety patients who were ≥30 years old, whose previous PCP had retired and who responded to a mailed questionnaire 1 year after linkage with a new PCP.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

The questionnaire assessed perceptions of choice, satisfaction, trust, and retention of the PCP. During the intervention period, 85% of subjects obtained a new PCP. Intervention subjects were more likely to perceive that they chose their PCP (78% vs 22%; P < .001), to retain their PCP at 1 year (93% vs 69%; P < .001), and to report greater overall satisfaction with the PCP (67% vs 57%; P < .01), compared to control subjects who were assigned to a PCP. The intervention subjects also reported greater trust in their PCP on most measures, but these differences did not remain statistically significant after adjustments for patient age, gender, ethnicity, education, and health status.

CONCLUSIONS

Encouraging patients to choose their PCP can result in mutually beneficial outcomes for both patients and providers, such as greater overall satisfaction and duration of the relationship. Further research is needed to identify the types of information most useful in making this choice and to understand the relevant underlying patient expectations.

Keywords: patient choice, provider selection, patient-provider relationshiop, satisfaction, primary care

The ability of patients to choose their primary care provider (PCP) is a highly valued element of health care in the United States.1–6 Patients often make these choices several times during their lives, such as when their PCP retires, moves, or becomes unavailable due to changes in health insurance plans. The scant current evidence suggests that restrictions on choice may undermine patients' satisfaction and trust in their physicians, with potential adverse consequences to adherence with medical recommendations and to continuity of care.5–12 Whether patient choice of a provider creates tangible, downstream benefits is unclear.

Insurance companies and managed-care organizations (MCOs) often have logistical or financial incentives to limit the number of choices available to patients, e.g., restricting choice to contracted physicians or to physicians in preferred-provider arrangements. In many settings, when a PCP retires or moves, a new provider simply assumes the previous PCP's entire patient panel with little attention to individual patient preferences. Even when patients have a nominal choice, the lack of provider-specific information may limit patients' ability to make an informed choice among the available PCPs.

Health care organizations, however, generally include relatively large numbers of PCPs, even in group or staff model HMOs. It is plausible that given both the opportunity and the appropriate information to make a choice, most patients could find a compatible PCP within their network, and that the act of choosing might lead to a stronger patient–provider relationship. Indeed, previous studies from a large, group model HMO suggest that the perception of having chosen one's PCP is associated with greater patient satisfaction with the physician, more trust in the physician, and greater adherence to prevention measures compared to persons who were assigned a PCP.3,11,12 These observational studies suggest an association between satisfaction and choice but do not establish a causal link between enabling patients to choose their PCP and subsequent ratings of the PCP. Moreover, they give little insight into the types of information that patients would find most helpful in making their choice.4

To begin addressing these issues, we conducted a randomized controlled trial in a large HMO of an intervention to assist in the selection of a new PCP, involving patients whose previous PCP had recently retired. The study compared the intervention to the existing “usual” method of assigning patients to a new provider after their current PCP retires. We assessed patients' subsequent perceptions of having made the choice and of the selection process, their overall satisfaction with and trust in the PCP, and maintenance of the patient–provider relationship 1 year after the linkage.

METHODS

Study Setting

The study was conducted within the Department of Medicine at the Santa Clara Medical Center of the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program, Northern California (KP), a large, group model HMO. At the outset of the investigation period (November 1998), there were approximately 162,000 members and 80 adult PCPs at the Santa Clara Center.

Patient Sources and Study Design

Eligible subjects were adult members, age 30 years or older, who were enrolled in the HMO, and whose PCP had retired immediately prior to the study period (N = 3,274; 2 PCPs). We deliberately excluded adult patients between 18 and 29 years of age because these patients as a group historically have had little contact with the health system or with their PCPs especially within a 1-year (follow-up) period. Only 1 randomly selected member per family was eligible for the study. Using an SAS random number generator, version 6.0 (SAS, Inc., Cary, NC), the project manager generated the allocation sequence and assigned each subject to 1 of 3 study arms in equal numbers: the control (usual practice) arm and 2 intervention arms. Research assistants used this random assignment for all subsequent portions of enrollment and data collection. The intervention arms differed in the amount of information available to patients in making their selection of a provider, as described below. The usual practice for patients of a retiring PCP involved a letter announcing the retirement, and indicating the name of the new PCP who was assuming the patient panel, i.e., an explicit assignment.

At the outset of the study, control subjects received the letter informing them only of their former PCP's retirement and their assignment to a new PCP. All intervention subjects received a letter that advised them to choose a new PCP either by telephone or through a special study website. The telephone number connected these subjects to a research assistant who used the same website to assist in the choice.

We monitored the health plan databases for 8 months following the initial contact letter to identify all new patient linkages with a PCP, i.e., the patient becomes part of the PCP's patient panel. Linkage resulted from either provider selection (intervention arms) or assignment (control arm) and did not require that the patient actually saw the provider for either study arm. All subjects in each arm who had linked with a PCP within this window received a mailed questionnaire to assess study outcomes 1 year after the linkage occurred, regardless of how the linkage was accomplished. Given the nature of the study, blinding was not possible. The Kaiser Foundation Research Institute Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Intervention Arm: Choice

There were 2 distinct Choice formats. In both formats, patients could access provider-specific information on all available PCPs, including gender, race/ethnicity, languages spoken, medical school, residency and fellowship training, areas of clinical interest, and personal interests or hobbies. Patients could review the information in any order. In addition, patients completed a 9-item questionnaire based on the Patient Provider Orientation Score (PPOS), which assessed preferences for shared medical decision making.13 All PCPs at the study site had previously completed the same questionnaire. In the first format (Informed Choice), patients could choose a PCP based only on the provider-specific information, i.e., without access to provider PPOS information; whereas in the second format (Guided Choice), patients received the names of PCPs with beliefs similar to their own regarding medical decision making in addition to all of the information available under the first format. For the analyses presented in this manuscript, we have collapsed both intervention formats into a single intervention arm because there were no significant or consistent differences in outcomes between the formats. In the unadjusted models, there was a trend for the Guided Choice subjects to report greater trust in their PCP and to have a better perception of the selection process. These effects were small and not statistically significant, perhaps due in part to a sample size insufficient for detecting differences between the intervention arms. Throughout the study, subjects in either the intervention arm or the control arm could request a specific PCP by name, as long as that PCP was accepting new patients. All subjects also could call Patient Services at any time to obtain or change their PCP via usual selection processes, thus bypassing the intervention. Patient Services staff did not have routine access to the provider-specific information available to intervention subjects, nor were they instructed systematically to offer callers any unrequested PCP-specific information. The staff, however, did attempt to answer patient questions to the best of their knowledge. Because they work in the same facilities as the PCPs, it is likely that the Patient Services staff had some familiarity with many of the physicians. In the absence of patient questions, the staff simply linked patients to an available PCP.

Patient Survey Contents and Response Rates

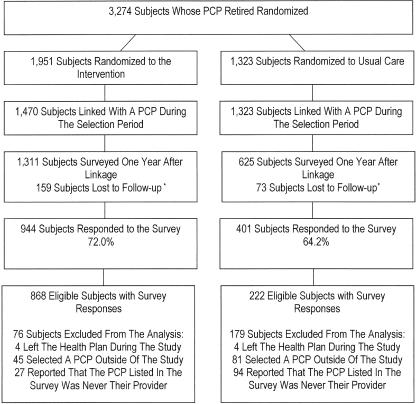

One year following linkage, we surveyed subjects who had obtained a new PCP during the linkage period. We excluded 232 subjects who had left the health plan, who had died, or for whom we could not find correct contact information. To reduce survey costs, we also randomly sampled 50% of the remaining 1,250 Control subjects. Overall, 1,936 Intervention and Control subjects received a mailed, self-administered questionnaire (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Trial flow diagram. *There were 232 subjects who left the health plan, died, or for whom we could not find correct contact information during the study period. We randomly sampled 50% of the remaining control subjects to decrease costs.

To evaluate patient perceptions of the choice process, subjects were asked whether they had chosen their PCP or were assigned a PCP by the health plan. Subjects who reported having chosen their PCP were then asked to rate their experience with the selection process using statements on the sufficiency of the number of PCPs from which to choose, the sufficiency of information for making a choice, whether they had a clear idea of what they wanted at the time of choice, and whether they felt rushed in making the choice. Responses used 6-point Likert scales (from 1, “Strongly Disagree” to 6, “Strongly Agree”); we grouped responses of “Strongly Agree” and “Moderately Agree” together when using dichotomous outcomes.

Subjects reported their satisfaction with their PCP and with the health system using 12 items based on the Medical Outcomes Study.14 Responses used a 5-point Likert scale, which ranged from 1, “Excellent” to 5, “Poor” with an additional option of “Don't Know.” Responses of “Don't Know” received a zero value in the analysis of satisfaction as a dichotomous outcome, i.e., “Excellent and Very Good,” or not, and were excluded in the analysis of satisfaction as a continuous variable. The primary focus was on patients' overall satisfaction with their PCP and retention of the PCP after 1 year. The survey also included questions on whether patients usually saw their PCP for their medical problems, satisfaction with the health system, and satisfaction with various aspects of their PCP's practice style: the amount of time the PCP spent with the patient during visits, explanations provided, technical skills, personal manner, use of the latest technology, focus on prevention, concern for the subject's well-being, listening skills, familiarity with subject's medical history, and level of shared decision making. In addition, subjects indicated whether they would recommend their PCP to a friend or family member.

Subjects reported their trust in the PCP by indicating their level of agreement (from 1 = “Totally Disagree” to 5 = “Totally Agree”) with 9 items: whether the PCP placed the patient's needs first, whether the patient always tried to follow the PCP's advice, trust in the PCP's judgments about medical care, trust that the PCP placed the patient's medical needs above all other considerations including costs, whether the PCP was well-qualified to manage the patient's medical problems, whether the PCP was honest in reporting medical errors, whether the PCP knew the patient well, confidence that the PCP always provided the best possible medical care, and whether the PCP and the patient shared similar values with respect to health care. Six items were taken from a previously published measure of patient trust.11 Two items had been previously developed and used but not published. The final item was added for the current study. Subjects reported their trust in the health system by indicating their level of agreement using the same scale as above for 2 items: trust to connect patients to the best PCP for their health care and trust to place patients' medical needs above all other considerations. We grouped responses of “Totally Agree” and “Agree” in the analysis of trust as a dichotomous outcome.

Subjects reported their perceptions of barriers to care access created by the PCP using 3 items that addressed whether the PCP interfered with patients' ability to access specialists, medications, and medical tests. The 6-point Likert scale responses ranged from 1, “Strongly Disagree” to 6, “Strongly Agree.” Responses of “Strongly Agree” and “Moderately Agree” received a value of 1 in the analysis of Access to Care as a dichotomous outcome.

The overall survey response rates were 72% and 64% for the intervention and control arms, respectively. From a total of 1,345 survey responses, we excluded from the analyses 8 subjects who had left the health plan during the study period, 126 subjects who selected a PCP outside of the study area, and 121 subjects who reported that the PCP listed on the survey was never their provider (Fig. 1). We chose these a priori exclusion criteria because subjects who never linked with a provider or who denied that a provider was ever their PCP would not have had the same opportunity to develop a patient–provider relationship as the study subjects did, and could not comment on their satisfaction with or trust in the provider. Similarly, we could not have captured complete utilization, provider, or survey data on subjects who chose a physician outside of the study area.

Statistical Analyses

The unit of randomization and analysis was the patient. We also used an intention-to-treat approach, in which the analyses were based on all randomized patients, i.e., subjects were part of their original study arm independent of how they actually chose their PCP. Initial univariate and bivariate analyses examined demographic variables in subjects in the intervention and control arms using standard χ2t test methods. All item responses were evaluated as both continuous and dichotomous outcomes. Comparisons were repeated after adjusting for any patient demographic differences between arms, using multivariate linear and logistic regression models. To account for potential clustering effects among patients of the same PCP, we used the cluster function in STATA 6.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex).15 All analyses were performed both before and after excluding the 12% of respondents who reported that they had not yet visited their PCP. The rationale for analyzing the patients who did not have an office visit was that some, e.g., healthy, younger patients, may have interacted with their PCP or his/her staff only by telephone, and may have developed impressions of their level of satisfaction.

RESULTS

PCP Linkage

Of the 3,274 potentially eligible study subjects, 2,793 subjects (85%) were linked with a health plan PCP during the 8-month intervention period (Fig. 1). Linkage rates were higher for the control arm because all of these subjects were explicitly assigned to a new PCP (75.3% and 100% for the intervention and control arms, respectively). Intervention subjects linked with 61 different PCPs. Control subjects were assigned initially to 1 of 3 different PCPs. The assigned PCPs had slightly higher average patient satisfaction scores in the routine health system surveys compared to the average of all PCPs at the medical center; this difference was not statistically significant (4.3 vs 4.1, respectively, on a 5-point scale with 5 indicating excellent satisfaction; P = .43). Furthermore, control subjects using existing health system channels eventually linked with a total of 27 PCPs during the study. Among intervention subjects, 61% used the intervention to select their PCP. The remainder of the intervention subjects linked with a PCP using existing channels.

Characteristics of Survey Respondents

Among the 1,090 eligible respondents, subjects in the intervention and control arms were similar with respect to gender, educational level, self-reported health status, and frequency of visits to the PCP during the study period (Table 1). Most subjects (88%) saw their PCP at least once, with a mean number of 3 visits to their PCP during the study year. The intervention subjects, however, were slightly older and more likely to report being white, compared to control subjects.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Intervention (N = 868) | Control (N = 222) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and health status | |||

| Mean age, y (SD) | 63.7 (13.0) | 60.7 (14.7) | .003 |

| Female, % | 46.0 | 45.0 | .79 |

| High school graduate, % | 89.8 | 90.2 | .87 |

| White ethnicity, % | 79.7 | 72.5 | .02 |

| Health status (excellent or very good), % | 36.3 | 40.4 | .27 |

| Visits to personal PCP during study | |||

| Visit ≥1, % | 88.0 | 85.6 | .98 |

| Mean number of visits (SD) | 3.3 (3.1) | 2.9 (2.8) | .10 |

Perceptions of the Selection Process

Intervention subjects were much more likely to perceive that they had personally chosen their PCP compared to control subjects who had been explicitly assigned a new PCP (78% vs 22%; P < .001; Table 2). Among subjects who reported that they had chosen their PCP, we found no significant differences between study arms in perceptions of the selection process; intervention subjects tended to perceive that they had a sufficient selection of PCPs from which to choose in comparison to control subjects (73% vs 60%, respectively; P < .085), but this association did not reach a statistically significant level. Of the patients in the control arm (22%) who perceived that they had chosen their PCP, most (65%) eventually did link with another PCP (27 total) using existing health system channels. The differences with respect to perceptions of choice remained statistically significant after adjustments for patient age, ethnicity, gender, education, health status, and potential clustering by PCP (odds ratio [OR], 11.9; P < .0001; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 6.1 to 23.4).

Table 2.

Perceptions of the PCP Selection Process

| Intervention (N = 856) | Control (N = 208) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of choice, N | |||

| Chose PCP (vs being assigned), %* | 77.5 | 22.1 | <.001 |

| Perceptions of the selection process, N† | 663† | 46† | |

| Sufficient selection of PCPs, % | 72.7 | 60.0 | .08 |

| Sufficient information to choose, % | 69.0 | 63.4 | .45 |

| Clear idea of criteria, % | 82.3 | 80.5 | .76 |

| Sufficient time to make choice, % | 64.1 | 60.0 | .61 |

Differences remain statistically significant after adjustment for patient age, gender, ethnicity, education, health status, and potential clustering by PCP using logistic regression models.

In subjects who reported that they had chosen their PCP: % reporting “Strongly Agree” or “Moderately Agree,” using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 6 = Strongly Agree).

Satisfaction with PCP and the Health System

Compared to control subjects, intervention subjects were significantly more likely to have the same PCP after 1 year (93% vs 69%; P < .001), to see that PCP when they had a medical need (84% vs 74%; P < .01), and to report excellent or very good overall satisfaction with the PCP (67% vs 57%; P < .01; Table 3). The differences with respect to PCP retention and overall satisfaction remained statistically significant after adjustments for patient age, ethnicity, gender, education, health status, and potential clustering by PCP (OR, 6.4,P < .02, 95% CI, 1.5 to 26.9; OR, 1.4, P < .05, 95% CI, 1.0 to 1.9, respectively). Intervention subjects also reported greater satisfaction on average with several aspects of the PCP's practice style, such as the PCP's listening skills, but few of these differences reached statistical significance. Exclusion of subjects who had never visited their PCP during the study year did not change these findings. As expected, there were no differences between the study arms in satisfaction with the health system.

Table 3.

Patient Satisfaction with PCP and HMO*

| Patient Satisfaction with PCP | Intervention, % (N = 868) | Control, % (N = 222) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCP retention–patient with same PCP after 1 y† | 92.9 | 68.9 | <.001 |

| Patient usually sees PCP for medical needs | 83.5 | 73.5 | .002 |

| Overall patient satisfaction with PCP* | 67.1 | 57.0 | .01 |

| Satisfaction with PCP's personal manner | 77.5 | 70.6 | .04 |

| Satisfaction with PCP's concern for patient | 60.1 | 53.8 | .11 |

| Patient would recommend PCP to friends or family | 78.3 | 70.3 | .02 |

| Satisfaction with time PCP spent during the visit | 54.9 | 52.6 | .57 |

| Satisfaction with PCP's explanations | 61.2 | 58.3 | .46 |

| Satisfaction with PCP's technical skills | 57.6 | 51.9 | .16 |

| Satisfaction with PCP's use of latest technology | 46.0 | 42.5 | .38 |

| Satisfaction with PCP's focus on prevention | 63.0 | 58.5 | .26 |

| Satisfaction with PCP's listening skills | 64.6 | 58.0 | .09 |

| Satisfaction with PCP's familiarity with patient history | 43.5 | 37.8 | .16 |

| Satisfaction with the level of shared decision making | 52.7 | 49.2 | .39 |

| Overall patient satisfaction with the HMO | 71.7 | 74.9 | .37 |

Ratings used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = excellent to 5 = poor). Responses of “excellent” or “very good” were considered to reflect satisfaction.

Differences remain statistically significant after adjustment for patient age, gender, ethnicity, education, health status, and potential clustering by PCP using logistic regression models.

Trust and Perceived Barriers to Care

Compared to control subjects, intervention subjects were significantly more likely to report following the PCP's advice (77% vs 69%; P < .03), to feel that the PCP provided the best medical care (77% vs 70%; P < .05), and to believe that the PCP thought the same way as the patient (62% vs 52%; P < 0.02; Table 4). These subjects also were significantly more likely to believe that the PCP was well qualified (83% vs 75%; P < .02) and knew the patient well (39% vs 25%; P < .001). Intervention subjects also reported that the PCP created less of a barrier to care with respect to seeing a specialist (76% vs 66%; P < .01) or obtaining medications (81% vs 73%; P < .02). Except for the differences with respect to the PCP's familiarity with the patient (OR, 1.9; P < .02; 95% CI, 1.1 to 3.0), these differences did not remain statistically significant after adjustments for patient age, ethnicity, gender, education, health status, and potential clustering by PCP. Similarly, intervention subjects reported greater agreement with the other 4 trust items, but the differences did not reach statistical significance. Excluding the subjects without any visits did not alter these findings. As expected, there were no differences between arms in trust in the health system.

Table 4.

Patient Trust and Perceived Barriers to Care*

| Intervention, % (N = 868) | Control, % (N = 222) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient trust in the PCP | |||

| Patient always follows advice | 77.1 | 69.3 | .03 |

| PCP provides best medical care | 77.3 | 70.2 | .04 |

| Patient and PCP think in the same way | 61.6 | 51.7 | .02 |

| Perception that PCP is well-qualified | 82.6 | 74.9 | .02 |

| Perception that PCP knows me well† | 39.1 | 24.6 | <.001 |

| Patient trusts PCP's judgment | 80.8 | 78.5 | .47 |

| PCP is considerate of patient needs | 76.5 | 74.9 | .64 |

| PCP places patient needs above all else | 71.4 | 67.2 | .27 |

| PCP would reveal mistakes | 68.1 | 65.6 | .52 |

| Patient trust in the HMO | |||

| HMO connects patient with best PCP | 74.5 | 76.1 | .64 |

| HMO places patient needs above all else | 68.1 | 68.5 | .92 |

| Patient perceptions of barriers to care | |||

| Perceived access to specialist | 76.4 | 65.9 | .01 |

| Perceived access to medications | 80.8 | 72.7 | .02 |

| Perceived access to medical tests | 78.7 | 72.6 | .09 |

Trust in the PCP: % reporting “Agree” or “Totally Agree,” using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Totally Disagree to 5 = Totally Agree). Trust in the HMO and barriers to care: % reporting “Strongly Agree” or “Moderately Agree,” using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 6 = Strongly Agree).

Differences remain statistically significant after adjustment for patient age, gender, ethnicity, education, health status, and potential clustering by PCP using logistic regression models.

Role of Perception of Choice in Explaining Outcomes Differences

For each statistically significant outcome difference, i.e., the choice versus assignment comparison, we repeated the regression model after adding as a predictor whether the patient felt they had chosen or were assigned to their PCP. In each analysis, the intervention/control difference was essentially removed by this adjustment; and in each case, the added variable was significantly related to the outcome.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial evaluation of an intervention to encourage and assist patients in choosing a PCP. Previous observational studies3,11,12,16 found that patients who perceived that they had chosen their PCP were much more satisfied with their PCP than were patients who reported having been assigned, but these studies could not determine causality. Consistent with the findings of these studies, our intervention led to higher overall satisfaction with one's PCP, and a greater likelihood of remaining with the PCP at 1 year when compared to simply assigning patients to a PCP. Importantly, patients' reports that they had chosen their PCP appeared to explain the treatment difference.

There are several important implications for our findings. First, even in a setting of restricted physician availability, encouraging patients to choose their PCP, compared to simply assigning patients to a PCP, can achieve significant gains in patient satisfaction and retention of the PCP. On the basis of our findings, it would appear inadvisable for insurers or medical groups to have new physicians assume the patient panels of physicians who are retiring or otherwise become unavailable without soliciting patient input. Although assignment may appear to be logistically simpler, this benefit may be ephemeral. Many (31%) of the assigned patients switched PCPs during the year of follow-up in this study, and still remained significantly less satisfied as a group. In short, encouraging patient choice of a provider may be of mutual benefit to both patients and insurers or provider groups.

The second implication is that if further improvements are to be made in helping patients make satisfying choices of a PCP, a better understanding of the impact and levers of patient choice within various patient populations will be needed.17–21 For example, whether more detailed information, such as measures of quality or satisfaction, photographs, or comments of patients with similar needs, could improve further on this usual selection process remains an open question.

The benefits of the choice process in this study were not as strong as seen in previous observational studies.3 To a large degree, we expected this attenuation, given the use of an intention-to-treat approach, and given that this experimental study focused on the causal link between choice and downstream satisfaction with the patient–provider relationship. This study was designed to explicitly capture the method of provider selection, thus limiting the effects of selective patient recall, e.g., patients with a high degree of satisfaction with the PCP may feel that they originally had chosen the PCP when they had not.

It also is important to note that these findings may not apply to patients who have different expectations for and use of care, e.g., young, healthy adults.22,23 We, however, did not observe an interaction between age and choice in explaining patient satisfaction, which suggests that choice has similar importance across the adult age range. A second limitation of these analyses is the difference in “enrollment” (the proportion of subjects who were linked with a PCP during the study period) between intervention and control subjects. These differences are likely due to the fact that 100% of the control group was assigned, and hence eligible for a survey, whereas only 75% of intervention subjects had called to obtain a new PCP within the 8 months. In light of the 25% of intervention subjects without a PCP, we would encourage greater effort in the future to link patients with a PCP, including perhaps the assignment of a temporary contact provider for those patients who do not link with a provider during the choice period. Older, white patients were somewhat more likely to have linked with a PCP, reflecting the tendency of older subjects to choose a replacement PCP more promptly. Although the outcome differences persisted after adjusting for patient age and race, it is plausible that remaining, unmeasured differences could contribute to the differences in self-reported outcomes. Another limitation is that the PCPs with the greatest availability, i.e., those available for assignment, could have been the least desirable options for patients. To assess this possibility, we calculated the average patient satisfaction score for each PCP using routine health system patient surveys and, as noted earlier, found that the PCPs to whom control subjects were assigned actually had slightly higher than average scores (not statistically significant) at the outset of the study. In addition, the findings of this study may not generalize to the remaining health plan members who elected not to obtain a PCP at all, i.e., some patients may be unwilling to select a PCP, and forcing them to do so would not necessarily enhance subsequent satisfaction levels. Finally, the findings may represent a conservative estimate of the difference between the groups, given the exclusion of patients who left the health plan or selected a nonstudy PCP. These patients may have been less satisfied with the available choices of providers, with the health plan in general, or with their previous PCP. Including these patients may have lowered average levels of satisfaction for both groups. There was, however, a larger percentage of excluded patients in the control arm compared to the intervention arms; thus this exclusion may have resulted in smaller differences between the groups, i.e., a bias toward the null.

In conclusion, this randomized controlled trial suggests that encouraging patient choice of a primary care provider has subsequent tangible effects on patient satisfaction, trust, and retention of the PCP. Conversely, not soliciting patient input has significant downstream effects, such as frequent switching of PCPs. Further research is needed on patients' expectations and demands for care, and on the types of information valuable to making the choices.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eisenberg JM, Power EJ. Transforming insurance coverage into quality health care: voltage drops from potential to delivered quality. JAMA. 2000;284:2100–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis K, Collins KS, Schoen C, Morris C. Choice matters: enrollees' views of their health plans. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995;Summer:99–112. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmittdiel J, Selby JV, Grumbach K, Quesenberry CP., Jr Choice of a personal physician and patient satisfaction in a health maintenance organization. JAMA. 1997;278:1596–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser Family Foundation/Agency of Health Care Research and Quality. National survey on Americans as health care consumers: an update on the role of quality information http://www.ahcpr.gov/qual/kffhigh00.htm. Accessed December 12, 2000.

- 5.Robinson S, Brodie M. Understanding the quality challenge for health consumers: the Kaiser/AHCPR survey. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1997;23:239–44. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gawande AA, Blendon RJ, Brodie M, Benson JM, Levitt L, Hugick L. Does dissatisfaction with health plans stem from having no choices? Health Aff (Millwood) 1998;17:184–94. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.5.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmittdiel J, Grumbach K, Selby JV, Quesenberry CP. Effect of physician and patient gender concordance on patient satisfaction and preventive care practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:761–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annas GJ. Patients' rights in managed care- exit, voice, and choice. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:210–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707173370323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones TO, Sasser WE. Why satisfied customers defect. Harv Bus Rev. 1995:88–99. Nov-Dec. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27(suppl):110–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thom DH, Ribisl KM, Stewart AL, Luke DA. Further validation and reliability testing of the trust in physician scale. Med Care. 1999;37:510–7. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krupat E, Stein T, Selby JV, Yeager CM, Schmittdiel J. Choice of a primary care physician and its relationship to adherence among patients with diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:191–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krupat E, Rosenkranz SL, Yeager CM, Barnard K, Putnam SM, Inui TS. The practice orientations of physicians and patients: the effect of doctor-patient congruence on satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39:49–59. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin HR, Gandek B, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, McHorney CA, Ware JE. Patients' ratings of outpatient visits in different practice settings. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1993;270:835–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reference Manual Release STATA. 6.0. College Station, Tex: STATA Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kao AC, Green DC, Davis NA, Koplan JP, Cleary PD. Patients' trust in their physicians: effects of choice, continuity, and payment method. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:681–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates DW, Gawande AA. The impact of the Internet on quality measurement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19:104–14. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.6.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofer TP, Hayward RA, Greenfield S, Wagner EH, Kaplan SH, Manning WG. The unreliability of individual physician “report cards” for assessing the costs and quality of care of a chronic disease. JAMA. 1999;281:2098–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.22.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein A. Public release of performance data: a progress report from the front. JAMA. 2000;283:1884–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. The public release of performance data: what do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence. JAMA. 2000;283:1866–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spranca M, Kanouse DE, Elliot M, Short PF, Farley DO, Hays RD. Do consumer reports of health plan quality affect health plan selection. Health Serv Res. 2000;35:933–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hibbard JH, Jewett JJ. What type of quality information do consumers want in a health care report card? Med Care Res Rev. 1996;53:28–47. doi: 10.1177/107755879605300102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.David SP, Greer DS. Social marketing: application to medical education. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:125–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]