Abstract

BACKGROUND

Data about whether Asian Americans are a high-risk or a low-risk group for osteoporosis are limited and inconsistent. Few previous studies have recognized that the heterogeneity of the Asian American population, with respect to both nativity (foreign- vs U.S.-born) and ethnicity, may be related to osteoporosis risk.

OBJECTIVE

To assess whether older foreign-born Chinese Americans living in an urban ethnic enclave are at high risk of osteoporosis and to refer participants at high risk for follow-up care.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional survey and osteoporosis screening, undertaken as a collaborative project by the Chinese American Service League and researchers at the University of Chicago.

SETTING

Chicago's Chinatown.

PARTICIPANTS

Four hundred sixty-nine immigrant Chinese American men and women aged 50 and older.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Chinese Americans in this urban setting are generally recent immigrants from south China with limited education and resources: mean age at immigration was 54, 56% had primary only or no education, and 57% reported “fair” or “poor” self-rated health. Eighteen percent are uninsured and 55% receive Medicaid. Bone mineral density (BMD) of the calcaneus was estimated using quantitative ultrasound. Immigrant Chinese women in the study had lower average BMD than reference data for white women or U.S.-born Asian Americans. BMD for immigrant Chinese men in the study was similar to white men at ages 50 to 69, and lower at older ages. Low body mass index, low educational attainment and older age at immigration were all associated with lower BMD.

CONCLUSIONS

Foreign-born Chinese Americans may be a high-risk group for osteoporosis.

Keywords: bone density, Asian Americans, Chinese Americans, osteoporosis, emigration and immigration

Osteoporosis is a common condition among older adults. White postmenopausal women are perceived to be at greatest risk. This perception is based in part on the only nationally representative bone mineral density (BMD) data, collected by the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) in 1988 to 1994. NHANES III measured BMD of the femur by dual x-ray absorptiometry and oversampled Mexican Americans and African Americans.1 NHANES III found 17% of non-Hispanic white women aged 50 and older were osteoporotic (i.e., BMD >2.5 standard deviations below the mean of young non-Hispanic white women), 8% of older African-American women, and 12% of older Mexican-American women. Only 2% of older men were osteoporotic, using the same reference values.2 The greater prevalence of osteoporosis among non-Hispanic white women may be useful in clinical decisions; for example, the guidelines for risk assessment from the National Osteoporosis Foundation list white race as a nonmodifiable risk factor to be considered in decisions about whether to measure BMD.3

Asian Americans were not oversampled in NHANES III, and there are no representative national data to inform clinical perceptions of whether this is a low-risk group (like blacks) or a high-risk group (like whites). Evidence from other data sources is inconsistent. The National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment (NORA) is an extremely large convenience sample (N = 200,160) of women aged 50 and older recruited through primary care physicians. One percent of the sample identified as Asian American (n = 1,912), without specific information about nativity or ethnicity (e.g., Vietnamese).4 Part of the complexity of bone assessment is the multiplicity of technologies. NORA used 4 different types of peripheral densitometers: single energy x-ray absorptiometry at the heel, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry at the forearm and finger, and ultrasound at the heel. NORA found Asian-American women had the highest risk of low BMD of 5 race/ethnicity groups; the odds ratio of osteoporosis was 1.56 for Asian women compared to whites, after adjusting for many factors, including body mass index.4 However, contrasting evidence comes from the manufacturer of the ultrasound heel densitometer used by NORA (Hologic, Bedford, MA) who carried out their own studies to determine reference values. They found Asian-American women had higher estimated BMD than white women.5 Hologic only included U.S.-born Asian Americans in their sample. Thus, it is not clear whether Asian Americans are a high- or low-risk group, and whether the apparent heterogeneity is due to variation in nativity, ethnicity, or assessment technology (ultrasound vs x-ray).

It is possible that elderly Asian immigrants, such as inner-city Chinatown populations, may be at particularly high risk for osteoporosis.6 Many of these persons may have had poor nutrition in childhood, have thin body habitus, and have difficulty accessing medical care because of finances, lack of insurance, language, and distrust of the medical system.7–10 Asians constitute some of the fastest growing populations in the United States.11 Thus, from the vantage points of public health policy as well as individual clinical decision making, it would be useful to know if certain Asian populations do have higher risk for osteoporosis. Yet, relatively little research has been done in Asian communities, even in comparison to other vulnerable minority groups.12–16 Language and cultural barriers, a dearth of investigators, and a relative lack of prioritization by funders have contributed to this information void.

Therefore, a collaborative team from the Chinese American Service League (CASL), a social service agency, and the University of Chicago interviewed Chinese immigrants aged 50 and older living in Chicago's Chinatown about their health and immigration history, and measured heel BMD using ultrasound. The goals of the collaborative project were: 1) to determine the prevalence of low BMD in this population; 2) to refer persons with low BMD for follow-up care; 3) to learn what factors were associated with BMD in this population; and 4) to discover how to facilitate community-based participatory research among elderly Chinese immigrants.

METHODS

Population

Chinatown is a compact ethnic enclave on Chicago's south side. It is a densely populated area with about 10,000 Chinese residents. Most residents come from south China. Tract-level analysis of the 1990 census found that 41% of Chinatown households included someone aged 65 or older, and 90% of the elderly were economically disadvantaged.

This project focused on recruiting participants from 4 elderly housing complexes in and near Chinatown.

Project Development

The CASL was founded in Chicago in 1978 and has grown to become the Midwest's largest social service agency for immigrant Chinese and other Asians, serving more than 14,000 clients. CASL employs over 180 staff and encompasses activities such as youth educational programming, employment training, computer literacy, citizenship tutoring, and elderly services. The Elderly Services Department provides casework management, immigration and naturalization assistance, Title V employment services, social and recreational activities, counseling, homemaking services, senior advocacy, and adult day care services.

This project was initiated by a member of CASL's Associate Board (VK), which includes young, professional volunteers. In addition to fundraising, the Board implements projects that require more time and effort than CASL's employees may have outside their duties. With previous experience at osteoporosis screenings during street fairs, she spoke with the manager of CASL's Elderly Services Division (S-LC) and the executive director about the possibility of assessing osteoporosis prevalence among their elderly clients. CASL's goals were to screen elderly clients for osteoporosis, to give them feedback about whether they should seek further medical treatment, to support clients in successfully seeking care by providing names of local physicians, and to determine whether osteoporosis was widespread, in order to better tailor future health outreach programs. Furthermore, CASL felt that data documenting a significant health problem would enhance grant submissions for new programs addressing the health needs of seniors.

The board member contacted an academic physician she knew through his support of CASL (MHC), who suggested working with a colleague with research experience in osteoporosis epidemiology and immigrant health issues (DSL). This group broadened the original goals to include research questions about the epidemiology of osteoporosis among Chinese Americans.

CASL brought several concerns to a research partnership with the university. They wanted to ensure that screening follow-up and education were central goals of the joint effort and that findings would be accessible to CASL clients and administrators. Several meetings held before undertaking significant work allowed the exchange of ideas underpinning both service and research aims and established the necessary level of trust.

Structure and Financial Issues

The research group obtained funding from 2 local sources, the Center on Aging at the University of Chicago and National Opinion Research Center (which is funded by the National Institute on Aging), and the Hartford Center for Geriatric Excellence, Section of Geriatrics (Department of Medicine), University of Chicago. The Associate Board member who had initiated the project agreed to be Project Manager.

CASL proposed hiring home health workers from its Community Care Program as interviewers. This is a large program, with 97 homemakers serving 261 clients. The homemakers are mostly women in their fifties who speak the same dialects as the elderly Chinatown residents (Cantonese and Toisanese). Importantly, the homemakers also are conversant with the personal beliefs and value structure of the elderly population, and that expertise would be crucial to the project. Interviewers were paid at rates similar to university research assistants, which is significantly more than home health workers' pay. The manager of the Elderly Services Department identified and recruited CASL homemakers she believed possessed the requisite skills; most had health care training in China.

To maximize participation and be respectful of elderly clients' time, the research group paid subjects $10 for their time, which averaged slightly more than 1 hour.

Questionnaire Development

The research group developed a questionnaire in English whose domains included demographics, immigration, health history, Western and Chinese medications, tobacco, diet (to identify Western vs Asian diets and calcium intake), current physical and social activity, employment, medical insurance, and social support.

After review by the manager of CASL's Elderly Services, this draft was translated into Chinese by a native speaker, and then independently back-translated by one person who had never seen the English draft and by the Project Manager. Translator, back-translators, and researchers met to resolve translation issues. The translations of some questions were revised, and some questions were completely changed (e.g., the education response categories) to better reflect the Chinese experience. The English version was revised to match the altered Chinese (“re-centered”).

To determine comprehensibility for the targeted population, the instrument was pilot tested by the Project Manager on the interviewers. Further modifications were made and back-translated. Interviewers practiced administering the questionnaire on each other. They also attended an informational session about osteoporosis.

Two standard survey instruments were used also. The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to screen for cognitive function. We used a Chinese translation/adaptation tested by the MMSE developers, MiniMental LLC.17 The second survey instrument was drawn from the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). The Chinese version was translated and evaluated by the International Quality of Life Assessment Project. Both because of concern that our entire interview would place a burden on respondents, and because the validity of the subscales is not established for the Chinese American translation,18,19 we obtained permission to ask only selected questions from the SF-36. Functional limitations were assessed with a question drawn from the Chinese SF-36 about the level of restriction in performing activities such as moving a table, vacuuming the floor, or practicing Tai Chi.

The protocol was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent (in Chinese) was obtained.

Protocol and Recruitment

The project manager appointed 2 interviewers to be team leaders with direct responsibility for recruiting participants, scheduling and organizing screening/interview sessions, and managing equipment and forms. Team leaders and interviewers had worked together for years, facilitating group cohesion. Maximizing group autonomy ensured that the team developed a sense of ownership over the project, and became invested in maintaining high-quality execution. After each session, the team gathered to discuss any problems that occurred that day, and to plan improvements for the next session.

The protocol included the interview, height and weight measurement, ultrasound heel measurement, and a blood pressure reading.

Screening and interview sessions were held on weekends during summer 2001 at elderly housing buildings in Chinatown and at CASL's office. Because some people considered the screening unlucky, tempting disaster for their health by not leaving well enough alone, team leaders were reluctant to go door-to-door inviting participation. Instead, they convened community meetings to describe the screenings and posted flyers as reminders. Existing good will with building management smoothed the team's entry into buildings. Individual invitations were necessary, however, in the situation where building management was not Chinese and the population was of mixed ethnicity.

Recruitment was extraordinarily successful. The team's familiarity with the population helped generate positive word of mouth. People from the neighborhood who did not live in the elderly housing buildings also wanted the screening. Rejecting them would have risked damaging CASL's reputation for welcoming all who needed services. Therefore, community residents over age 50, but not resident in the target buildings, were included but not actively recruited.

Bone Densitometry

The Sahara Clinical Bone Sonometer (Hologic, Waltham, MA) was used to estimate BMD of the calcaneus. The Sahara measures the broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA, in dB/MHz) and speed of sound (SOS, in m/sec) of an ultrasound beam passed through the heel. The BUA and SOS are combined to yield an index (quantitative ultrasound or “stiffness” index), which is then used to estimate calcaneal BMD (in g/cm2). However, because the ultrasound beam passes through the heel, ultrasound measurements may reflect aspects of bone quality or microarchitecture not measured by an x-ray–based densitometer.20 The manufacturer's reference values for young white females were used to determine t scores. The t score is the number of standard deviations from the average bone density of young adults in their twenties, the age of peak bone density. We referred persons with a t score < −1.8 for follow-up care.21

The Sahara is portable. The foot is placed in a positioning device, and gelled transducers automatically converge to make direct contact with both sides of the heel, measuring heel width. The ultrasound measurement takes less than 10 seconds. Because this is a noninvasive radiation-free procedure, there are essentially no risks. A single machine was used for the study and 1 member of the research team was assigned to take measurements. A phantom supplied by the manufacturer was used to calibrate the machine before each screening session. The manufacturer specifies the coefficient of variation for estimated BMD at 3%, and the absolute precision at 0.014 g/cm2.

Analysis

First, we used the BMD t score to determine the proportion osteopenic (t score ≤−1.0) and osteoporotic (t score ≤−2.5) for 10-year age groups. We compared the average BMD by age with previously collected reference data. For men, there are only reference values for white men. For women, there are reference values for white, U.S.-born Asian-American and southern Chinese women.22

To examine predictors of BMD, we used ordinary least squares regression. Because of the strong and well-established relationships between BMD and age, and between BMD and sex, we did not carry out simple bivariate analyses of BMD with each potential predictor of BMD (such as education or current smoking). Instead of bivariate models, we examined each of the potential predictors in minimal multivariate models that included adjustment just for age and sex. These models also allowed the age effect to vary by sex (with interaction terms). We did not stratify by sex because the male sample was relatively small, and there were no significant interactions between sex and the predictor variables of interest in preliminary analyses. The BMD predictor variables we singly examined, adjusting only for age and sex, were body mass index (BMI) quartiles, education, age at immigration, self-rated health, functional limitations, help with daily tasks, insurance status, and lifestyle variables (current smoking, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, and dairy consumption), Because only 4 women reported current use of hormone replacement therapy, we did not include it among the lifestyle variables.

Then, we constructed a full multivariate model by including all moderately predictive (P < .1) variables (along with the age and sex adjustment). To present a parsimonious model, we then removed those variables that were not independently predictive at the same 0.1 significance level. Data were analyzed using Stata Statistical Software, Release 7.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex).

RESULTS

Four hundred sixty-nine persons were screened, 329 women and 140 men (Table 1). Participants included 63% of residents in the targeted buildings (n = 270) and community residents not from those buildings (n = 199). Age ranged from 50 to 98, with a mean of 71. Fifty-six percent had primary only or no education. Mean age at immigration was 54; only 5% were in the United States before the Immigration Act of 1965, which made immigration from Asian countries less restrictive. All interviews were conducted in Chinese. Fifty-seven percent of the population reported “fair” or “poor” health. Eighteen percent were uninsured; 55% received Medicaid.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Population

| Proportion (N = 469) | |

|---|---|

| Female | 0.70 (329) |

| Age | |

| 50–59 | 0.14 (66) |

| 60–69 | 0.31 (144) |

| 70–79 | 0.36 (164) |

| 80–89 | 0.18 (82) |

| 90–99 | 0.01 (5) |

| BMI quartiles | |

| <21.5 | 0.25 (115) |

| <24.0 | 0.26 (124) |

| <26.5 | 0.26 (123) |

| 26.5+ | 0.23 (107) |

| Education | |

| None or elementary | 0.56 (261) |

| Secondary or more | 0.44 (207) |

| Mean age at immigration (SD) | 54 (10.8) |

| Self-rated health | |

| Excellent | 0.02 (10) |

| Very good | 0.20 (92) |

| Good | 0.21 (95) |

| Fair | 0.44 (204) |

| Poor | 0.13 (62) |

| Functional limitations* | |

| None | 0.48 (226) |

| Moderate | 0.26 (122) |

| Major | 0.25 (115) |

| Receives help with tasks | 0.48 (225) |

| Insurance | |

| None | 0.18 (86) |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 0.33 (158) |

| Medicare | 0.12 (57) |

| Medicaid | 0.22 (102) |

| Private and other | 0.14 (64) |

Restriction in performing activities such as moving a table, vacuuming the floor, or practicing Tai Chi.

BMI, body mass index.

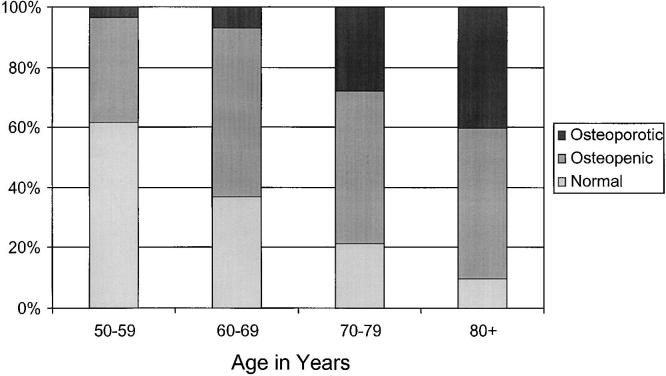

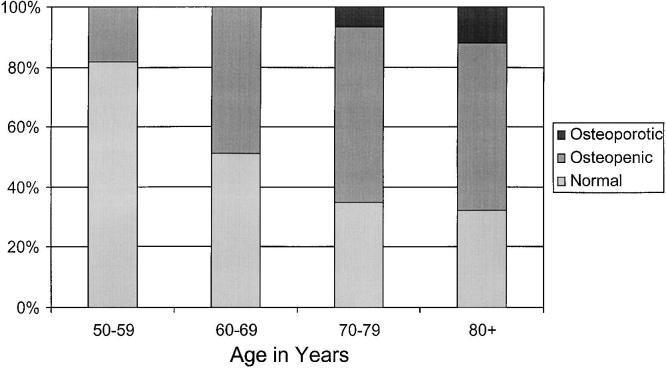

Figures 1 (women) and 2 (men) present the percentages of participants who were osteopenic and osteoporotic using a 10-year age range. Percentage osteopenic or osteoporotic increased with age and included at least half of the population at ages 60 and older. Few men were osteoporotic, while 28% of the women aged 70 to 79 and 40% of the women aged 80 and older were osteoporotic.

FIGURE 1.

Proportions of Chinese immigrant women who are osteopenic and osteoporotic, as estimated from ultrasound of the calcaneus. Osteopenic is defined as a t score <−1.0 and ≥−2.5, compared to young normal women, and osteoporotic is defined as a t score <−2.5.

FIGURE 2.

Proportions of Chinese immigrant men who are osteopenic and osteoporotic, as estimated from ultrasound of the calcaneus. Osteopenic is defined as a t score <−1.0 and ≥−2.5, compared to young normal women, and osteoporotic is defined as a t score <−2.5.

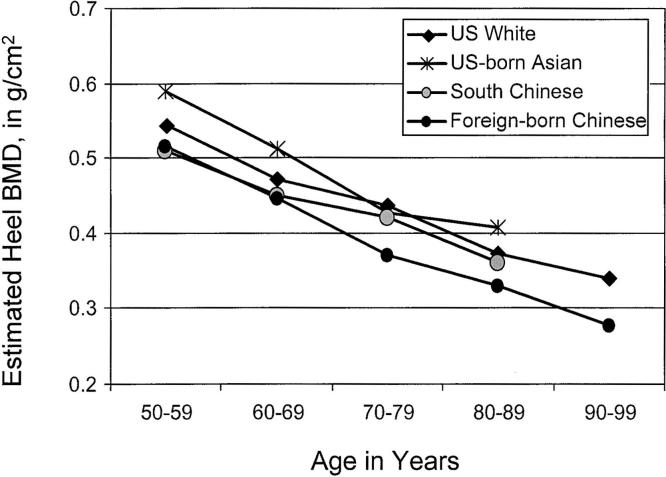

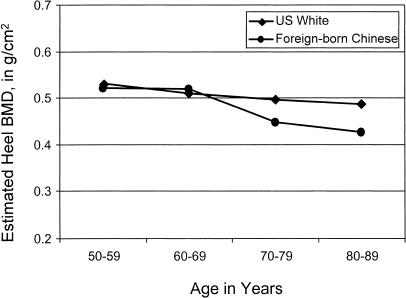

Figures 3 (women) and 4 (men) compare the average BMD by age with previously collected reference data. The population of foreign-born Chinese-American women in this study have lower average BMD at every age than do U.S. white women; they also have lower BMD than U.S.-born Asian Americans. At ages 50 to 69, the average BMD is the same for the foreign-born Chinese women and the reference series from south China, while the foreign-born Chinese women in the United States have a lower average BMD than the south Chinese women at ages 70 and older. Foreign-born Chinese men have a BMD at ages 50 to 69 similar to that of whites, and a lower average BMD at ages 70 and older.

FIGURE 3.

Comparisons of mean bone mineral density (BMD) by age for Chinese immigrant women with reference data for U.S. white women, U.S.-born Asian-American women,5 and women in southern China,22 as estimated from ultrasound of the calcaneus.

FIGURE 4.

Comparisons of mean bone mineral density (BMD) by age for Chinese immigrant men with reference data for U.S. white men, as estimated from ultrasound of the calcaneus.

Table 2 presents the minimal multivariate ordinary least squares regression models for potential correlates of BMD, adjusted for sex and age. Increasing BMI was strongly related to higher BMD. Poorer self-rated health, functional limitations, receipt of help with daily tasks, and lower educational attainment were all associated with lower BMD. Older age at immigration also was associated with a lower BMD. Insurance status was not associated with BMD, nor were 3 of the 4 lifestyle variables (smoking, exercise, and dairy consumption). However, alcohol consumption, reported by few participants, was strongly associated with higher BMD.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlates of Bone Density t Score Among Older Chinese Americans*

| Change in β Coefficient | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (per quartile) | 0.194 | 0.112 to 0.277 | <.001 |

| Education | |||

| Secondary or more | 1.00 | Ref | |

| None or elementary | −0.195 | −0.396 to 0.007 | .059 |

| Age at immigration (per 5 y) | −0.062 | −0.110 to −.014 | .011 |

| Self-rated health | |||

| Excellent, very good, or good | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Fair or poor | −0.223 | −0.415 to −.031 | .023 |

| Functional limitations† | |||

| None | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Moderate | −0.153 | −0.391 to 0.086 | .210 |

| Major | −0.361 | −0.638 to −0.085 | .010 |

| Receives help with tasks | −0.242 | −0.443 to −0.040 | .019 |

| Insurance | |||

| Private/Medicare/other | 1.0 | Ref | |

| Medicaid | −0.162 | −0.040 to 0.077 | .184 |

| None | 0.090 | −0.198 to 0.378 | .540 |

| Lifestyle | |||

| Current smoking (n = 22) | 0.154 | −0.149 to 0.456 | .318 |

| Any alcohol in past week (n = 34) | 0.645 | 0.286 to 1.004 | <.001 |

| Regular exercise (n = 123) | 0.054 | −0.155 to 0.264 | .612 |

| No dairy consumption (n = 111) | −0.042 | −0.259 to 0.175 | .704 |

Adjusted only for age and sex (and allowing the age effect to vary by sex), using ordinary least squares regression models.

Restriction in performing activities such as moving a table, vacuuming the floor, or practicing Tai Chi.

BMI, body mass index.

In the full multivariate model (Table 3), the effect of age on BMD was much stronger for women than men. At the baseline age in this study (50), there was little difference in BMD for women and men, adjusted for the other factors. Higher BMI, higher educational attainment, younger age at immigration, no receipt of help with daily tasks, and alcohol consumption were all independently associated with higher BMD.

Table 3.

Multivariate Correlates of Bone Density t score Among Older Chinese Americans*

| Change in β Coefficient | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age effect for female (per 5 y) | −0.210 | −0.275 to −0.145 | <.001 |

| Age effect for male (per 5 y) | −0.044 | −0.152 to 0.064 | .426 |

| Sex (female) | 0.187 | −0.353 to 0.728 | .497 |

| BMI (per quartile) | 0.154 | 0.071 to 0.237 | <.001 |

| Education | |||

| Secondary or more | 1.00 | Ref | |

| None or elementary | −0.234 | −0.431 to −0.037 | .020 |

| Age at immigration (per 5 y) | −0.048 | −0.095 to −0.002 | .042 |

| Receives help with tasks | −0.271 | −0.469 to −0.073 | .007 |

| Any alcohol in past week | 0.576 | 0.226 to 0.925 | .001 |

From a multivariate ordinary least squares regression model.

BMI, body mass index.

DISCUSSION

At ages 50 and older, women born in southern China and now resident in Chicago's Chinatown have low average calcaneal BMD, as assessed by ultrasound. Average BMD is lower than reference values for white women and U.S.-born Asian-American women. Foreign-born Chinese American men have lower BMD than white men at ages 70 and older. These data are consistent with findings from the NORA study, which reported that a heterogeneous group of Asian-American women had the lowest BMD of any racial/ethnic group, even after controlling for BMI.4 The large difference between foreign-born Chinese-American women and U.S.-born Asian-American women,5 together with our finding that older age at immigration is associated with lower BMD, strongly suggests that risk of osteoporosis varies by birthplace and age at immigration for Asian women in the United States, and may vary by ethnicity, because a high proportion of the reference series of U.S.-born Asian women were Japanese. Foreign-born Asian-American women, particularly those who immigrated recently, appear to be a high-risk group for osteoporosis. Interestingly, we found that average BMD at ages 50 to 69 was the same for women in southern China22 and women from southern China in the United States. The Chinatown residents aged 70 and older, both men and women, appear to be an especially frail population.

Several previous studies have suggested that Asians seem to have lower BMD than whites because they have smaller skeletons.23–25 The concern is that dual x-ray absorptiometry inadequately adjusts bone mineral content for bone size, and thus could spuriously find that persons with smaller skeletons systematically have lower BMD than they really do. However, it is not apparent why skeletal size would confound ultrasound heel measurements in the same way, since the width of the heel is measured by the densitometer.

Heel ultrasound identifies a lower percentage of persons as osteoporotic than does x-ray densitometry, and it has been suggested that a threshold of t score <−1.8 be used instead of <−2.5 for ultrasound to diagnose a similar proportion of the population as osteoporotic.21 Using that threshold (which we did use for referrals), a much higher percentage of persons would be identified as osteoporotic, for example 28% of men 70 to 79 and 56% of women aged 70 to 79.

Consistent with previous data,26 we found that low BMI was associated with lower BMD. While there is evidence that alcohol consumption decreases risk of osteoporosis,4 the magnitude of the association here may reflect the association of alcohol consumption with some aspects of acculturation or dimensions of health not captured by our self-rated health and functional limitations questions. While low use of hormone replacement therapy in this population may indicate that it is not acceptable as treatment, alendronate has been shown to be similarly effective in Asian and white populations.27,28

There are limitations to our data. Our target population included residents of elderly housing buildings, and they may differ from other elderly Chinese immigrants, even within Chinatown. We have no denominator for the “walk-in” participants who did not live in these buildings. Because participants had to leave their apartments to be screened, we may have under-represented the frailest. However, the familiarity of our interviewers with persons receiving homemaker services may have resulted in higher participation of persons in need of help with daily tasks. While Chinese Americans generally exceed the national average in educational attainment and income,29 the Chinatown population is relatively indigent. Immigrants who choose to live in an ethnic enclave may differ in many ways from those who do not. Finally, we do not know the consequences of osteoporosis in this population, specifically the strength of the association between low BMD estimated by heel ultrasound and fractures.

The research team has continued to work together in the evaluation and dissemination phases. We conducted door-to-door visits with participants advised to seek follow-up medical care for possible osteoporosis (or hypertension) to learn whether the advice was followed. For those who have not seen a provider, we asked the reasons. For participants who sought follow-up care, we asked whether there was further testing and what advice was given. We are designing educational presentations to be conducted by the interviewers at each building to discuss ways to prevent further bone loss and avoid falls.

All phases of this project have been collaborative between the community organization and the university. CASL collaborators proposed the screening, selected the target population, identified a team of professional and competent home care workers who were intimately familiar with the patients and study setting, created a mechanism to link clients with needed services, and provided legitimacy for the project within Chinatown. The community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach greatly enhanced the feasibility, quality, and impact of this study. Elderly immigrant Chinese populations are vulnerable and hard-to-access populations that do not receive sufficient attention from researchers or policy makers. Language barriers and distrust of outsiders can be difficult to surmount. University researchers could not have carried out this project without the collaboration of CASL. Regarding quality, the CASL team and health care workers played crucial roles in ensuring that questionnaire wording would be appropriate, and their knowledge of the community and respect within it led to high study enrollment. At the same time, the methodological rigor and scientific background of the university team allowed the CASL project to progress beyond a screening project of only local interest to a study that supplies osteoporosis information useful to a broader audience. The dissemination of these findings identifying foreign-born Chinese-American women as being at high risk for osteoporosis could help these patients receive more appropriate, individualized care from clinicians and may help direct more resources to indigent Chinese-American populations.

The major challenge to performing this CBPR was establishing a relationship of trust and understanding. It took time to learn the goals, concerns, working styles, and needs of each party. While statements of good will and a common vision were made at the beginning of the project, there was no substitute for developing a set of shared experiences in which logistical and methodological challenges were worked out in ways that would benefit the Chinatown community. The importance of visits to each party's home turf and dim sum lunches in Chinatown for social bonding is not to be underestimated. The major facilitator of the project was a diverse team who together shared the ultimate vision of improving Asian-American health, and who individually possessed the community, analytical, clinical, management, and political skills necessary for the project to succeed. It also helped that 2 of the participants were bridge people, a community activist familiar with academia through her legal training, and an academician who had done volunteer work in the Asian-American community. However, we believe that regardless of prior experience in CBPR, any group of community representatives and academicians who share the mission of promoting health in the community and who appreciate the power of rigorous data analysis can develop successful projects over time.

In summary, foreign-born Chinese-American women appear to be a high-risk group for osteoporosis, with BMD values even lower than white women. Foreign-born Chinese American men in the study have BMD values similar to white men at ages 50 to 69, but lower BMD at older ages. For both men and women, the Chinatown population aged 70 and older appears to be especially frail and at high risk of osteoporosis. Low body mass index, low educational attainment, and older age at immigration are all associated with lower BMD in this population. The CBPR approach was essential to the success of this study. The familiarity of CASL with Chinatown and its elderly residents made this hard-to-access population enthusiastic participants in the project. In turn, this project provided CASL with concrete data about the frailty and health problems of the elderly population which it serves.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mandy Manchi Sha, Lijun Chen, and Xiaoquan Zhu for translation; Kathleen Cagney for help with survey development; Phil Schumm, Ming Wen and Xiaoquan Zhu for assistance with the database; Dr. Phuong Tran and the Weiss Health Center for lending their densitometer to the project; Lei Liu for Chinese typing; and especially the team leaders and interviewers: Mei Sheung Lee (team leader), Xing Qun Liang (team leader), Yuan Cheng He, Dao Zhen Liu, Shiu Lang Kwan Liao, Xiu Qiong Wu, Xiu Fang Zhu, and Sau Yuet Yun.

Dr. Chin did not participate in the Journal of General Internal Medicine's editorial process for this paper.

This project was funded by the Center on Aging at the University of Chicago and the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) (NIA P30 AG-12857-06) and The Hartford Center for Geriatric Excellence, Section of Geriatrics (Department of Medicine), University of Chicago. Dr. Chin is a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar.

REFERENCES

- 1.Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, et al. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:468–89. doi: 10.1007/s001980050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Looker AC, Orwoll ES, Johnston CC, Jr, et al. Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older U.S. adults from NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1761–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.11.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Osteoporosis Foundation. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Physician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siris ES, Miller PD, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. JAMA. 2001;286:2815–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nattress S, Orwell E, Tylavsky F, et al. Male and ethnic reference values for the Sahara Clinical Bone Sonometer. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(suppl):501. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanjasiri SP, Wallace SP, Shibata K. Picture imperfect: hidden problems among Asian Pacific islander elderly. Gerontologist. 1995;35:753–60. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma GX. Barriers to the use of health services by Chinese Americans. J Allied Health. 2000;29:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma GX. Between two worlds: the use of traditional and Western health services by Chinese immigrants. J Community Health. 1999;24:421–37. doi: 10.1023/a:1018742505785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang M, Lee E, Woo K. Income, language, and citizenship status: factors affecting the health care access and utilization of Chinese Americans. Health Soc Work. 1998;23:136–45. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabora BL, Flaskerud JH. Mental health beliefs, practices, and knowledge of Chinese American immigrant women. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1997;18:173–89. doi: 10.3109/01612849709012488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollard KM, De Vita CJ. A portrait of Asians and Pacific Islanders in the United States. Stat Bull Metrop Insur Co. 1997;78:2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saphir A. Asian Americans and cancer: discarding the myth of the “model minority.”. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1572–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo J, Porter K. Health status of Asian Americans: United States, 1992–94. Adv Data. 1998;298:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Behavioral risk factor survey of Chinese–California, 1989. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992;41:266–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang CY, Abbott LJ. Development of a community-based diabetes and hypertension preventive program. Public Health Nurs. 1998;15:406–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1998.tb00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McPhee SJ, Stewart S, Brock KC, Bird JA, Jenkins CN, Pham GQ. Factors associated with breast and cervical cancer screening practices among Vietnamese American women. Cancer Detect Prev. 1997;21:510–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR Mini-Mental State. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren XS, Amick B, III, Zhou L, Gandek B. Translation and psychometric evaluation of a Chinese version of the SF-36 Health Survey in the United States. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1129–38. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang DF, Chun CA, Takeuchi DT, Shen H. SF-36 health survey: tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability in a community sample of Chinese Americans. Med Care. 2000;38:542–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200005000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prins SH, Jorgensen HL, Jorgensen LV, Hassager C. The role of quantitative ultrasound in the assessment of bone: a review. Clin Physiol. 1998;18:3–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.1998.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frost ML, Blake GM, Fogelman I. Can the WHO criteria for diagnosing osteoporosis be applied to calcaneal quantitative ultrasound? Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:321–30. doi: 10.1007/s001980070121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kung AW, Tang GW, Luk KD, Chu LW. Evaluation of a new calcaneal quantitative ultrasound system and determination of normative ultrasound values in southern Chinese women. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9:312–7. doi: 10.1007/s001980050153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marquez MA, Melton LJ, 3rd, Muhs JM, et al. Bone density in an immigrant population from Southeast Asia. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:595–604. doi: 10.1007/s001980170083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross PD, He Y, Yates AJ, et al. Body size accounts for most differences in bone density between Asian and Caucasian women. The EPIC (Early Postmenopausal Interventional Cohort) Study Group. Calcif Tissue Int. 1996;59:339–43. doi: 10.1007/s002239900137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhudhikanok GS, Wang MC, Eckert K, Matkin C, Marcus R, Bachrach LK. Differences in bone mineral in young Asian and Caucasian Americans may reflect differences in bone size. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:1545–56. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.NIH Consensus Development Conference on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Theraphy. Bethesda, Md: Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy NIH Consensus Statement. March 27–29, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kung AW, Yeung SS, Chu LW. The efficacy and tolerability of alendronate in postmenopausal osteoporotic Chinese women: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;67:286–90. doi: 10.1007/s0022330001142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wasnich RD, Ross PD, Thompson DE, Cizza G, Yates AJ. Skeletal benefits of two years of alendronate treatment are similar for early postmenopausal Asian and Caucasian women. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9:455–60. doi: 10.1007/s001980050171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waters MC, Eschbach K. Immigration and ethnic and racial inequality in the United States. Annu Rev Sociol. 1995;21:419–46. [Google Scholar]