Abstract

CONTEXT

Understanding students’ perceptions of and responses to lapses in professionalism is important to shaping students’ professional development.

OBJECTIVE

Utilize realistic, standardized professional dilemmas to obtain insight into students’ reasoning and motivations in “real time.”

DESIGN

Qualitative study using 5 videotaped scenarios (each depicting a student placed in a situation which requires action in response to a professional dilemma) and individual interviews, in which students were questioned about what they would do next and why.

SETTING

University of Toronto.

PARTICIPANTS

Eighteen fourth-year medical students; participation voluntary and anonymous.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURE

A model to explain students’ reasoning in the face of professional dilemmas.

RESULTS

Grounded theory analysis of interview transcripts revealed that students were motivated to consider specific actions by referencing a Principle (an abstract or idealized concept), an Affect (a feeling or emotion), or an Implication (a potential consequence of suggested actions). Principles were classified as “avowed” as ideals of our profession (e.g., honesty or disclosure), or “unavowed” (unacknowledged or undeclared, e.g., obedience or allegiance). Implications could also be avowed (e.g., concerning patients) or unavowed (e.g., concerning others); but students were predominantly motivated by considering “disavowed” implications: those pertaining to themselves (e.g., concern for grades, evaluations, or reputation), which are actively denied by the profession and discouraged as being inconsistent with altruism.

CONCLUSIONS

This “disavowed curriculum” has implications for education, feedback, and evaluation. Instead of denying their existence, we should teach students how to negotiate and balance these unavowed and disavowed implications and principles, in order to help them develop their own professional stance.

Keywords: undergraduate education, medical education, professionalism, evaluation

Teaching and evaluating professionalism remains a priority in health professional education, and has been the subject of much research over the last several years.1,2 However, students continue to report being subjected to (or participating in) unprofessional or unethical behavior.3–5 Some authors have reported students' sense of frustration and futility in the face of dilemmas, along with a concern that students often feel pressured to behave “unethically.”6 An important step in addressing this phenomenon is understanding students' perceptions of the lapses they are reporting. For example, a behavior-based taxonomy demonstrated that what students perceive as lapses in professionalism did not map easily onto the standard, abstract definitions that are often adopted by professional organizations.7

Understanding students' perceptions of lapses is an important step, but alone it is insufficient; an understanding of why students sometimes feel pressured to behave unprofessionally, and how they respond to these pressures, is essential to developing interventions aimed at education and remediation. In two recent studies, we used written essays to develop and refine a model to explain students' reasoning strategies in the face of professional dilemmas they had encountered.8,9 In almost all cases, students “dissociated” from the lapse, either by condescending (e.g., becoming outraged, or “washing their hands” of the situation) or by invoking “identity mobility” (oscillating between two or more potential roles, e.g., student and caregiver, and acting out of self-preservation, obedience, or deference). However, because these lapses had already occurred, students may have developed fairly sophisticated reasoning strategies regarding their actions as they re-storied the incident to write about it. They may also have selectively reported only those lapses in which they felt they had ultimately behaved “respectably,” and of course the lapses and scenarios could not be standardized across students.

This work has therefore provided insight into students' “posthoc” rationalizations or justifications of behaviors already enacted; the next step is to minimize the problems of hindsight bias by investigating what factors students weigh when considering action in the moment. An understanding of students' “real time” motivations is essential for the development of effective feedback and evaluation.

Toward these ends, the purpose of this study was to utilize representative, realistic, and standardized professional dilemmas to obtain insight into students' reasoning and motivations in real time.

METHODS

Subjects

Potential subjects were all fourth (final)-year medical students at the University of Toronto (N = 190). The University of Toronto has a traditional 4-year undergraduate medical curriculum with classroom teaching, seminars, and problem-based learning in the first 2 years, and clinical clerkships in the final 2 years. At the time of this study, there was no formal “professionalism” curriculum in place, although students did receive teaching in medical ethics.

The Cases

Five scenarios, or vignettes, were developed from material from previous studies. Each scenario represented a real life situation that had been reported to us anonymously by medical students at three universities, with details altered to protect the identity of persons involved. The five cases were chosen to include a variety of typical professionalism issues, as described in our original work (e.g., role resistance, communicative violations, accountability, and objectification),7 and had all provoked significant debate about professionalism issues among the students (and researchers) in their initial reporting. Each scenario was developed into a videotaped segment approximately 1 to 2 minutes in length, which depicts a student who is placed in a situation which requires action in response to a professional dilemma. Each video ends at the point at which the student must act. (See Box 1 for a summary of the scenarios.)

Box 1.

A Summary of the Videos Developed from Students' Own Descriptions of Lapses in Professionalism that They Had Witnessed

| Video 1: |

| A clerk is walking down the hall with the attending surgeon, at the end of ward rounds. She is telling the surgeon that the patient they are about to see wants to know her test results. The patient is post–liver transplant, and on a postop film they discovered a large lung mass and no one has told her. Every day, the patient asks about the results, and the clerk feels awkward not disclosing the information. The surgeon tells the clerk that that is up to the other team (medicine) and not up to them, as they are just responsible for the surgery and postop care. The surgeon then gets paged away, and the student enters the patient's room. The patient is in good spirits, and wants to go home soon, but again asks for her test results. Scene ends. |

| Video 2: |

| A medical team is thrilled that they're done by 5 pm on a Friday afternoon, and they all decide to go out for drinks. The clerk arrives, and they invite him along, as it's his last day. However, the clerk has not quite finished his work—he has a patient that he's worried about, who has high blood sugars and may need insulin over the weekend. The resident tells the clerk that it's no big deal, it can wait until Monday. When the student protests, the resident tells him again not to worry, that there's an on-call team that can deal with it, and then asks if he's coming for drinks. Scene ends. |

| Video 3: |

| A clerk is about to go into a patient's room, when an intern interrupts to tell her that they're about to do a bone marrow in emergency, and that she should go see it. The clerk, frustrated, tells him she can't go and watch, because she promised to see one of her chronic patients, who “takes forever.” She explains to him that this patient is quite demented, and although he's been told every day that he's going to a nursing home, he forgets and keeps asking when he can go home. When he realizes he's being “placed,” he gets very confused and angry, and then he cries. It takes a long time to calm him down, and it's distressing for the student to go through this with him every day. The intern hints that “Well, if he doesn't remember anyway…” but then trails off and leaves. The scene ends with the clerk entering the patient's room. |

| Video 4: |

| A group of clerks (male and female) are in a fertility clinic. The staff doctor enters with a male patient, and begins enthusiastically teaching them about infertility. He asks the patient to undress, and although uncomfortable, he does. The doctor continues teaching, and asks one of the (female) clerks to come over and palpate the genitalia. No one is wearing gloves, and no one has spoken to the patient, who is obviously uncomfortable. After they are done with the exam, the doctor leaves with the patient, and says “I'll be back in a couple of minutes with the next patient.” Once they leave, the students express their horror and discomfort with the situation, but realize that he's coming back in a minute WITH another patient. Scene ends. |

| Video 5: |

| A clerk and her resident are outside a patient's room, discussing the thoracentesis they are about to perform (the clerk's first), and he tells her they're pretty easy if you know what you're doing. In the next scene, they are all set to do the procedure—the patient is draped, the clerk is gloved with needle in hand, and the resident is behind her. Just as the freezing is going in, a nurse enters the room, turns to the resident, and in a friendly voice, says “Hmm—she must be pretty good for you to not even be scrubbed in!” Then she asks the student: “How many of these have you done before?” Scene ends. |

Procedure

After research ethics approval was obtained, participants were solicited by a group e-mail to the class, with responses being sent directly to a research assistant (RA). Monetary remuneration was offered for participation, which was entirely voluntary. Students were informed that the interview transcripts would remain anonymous and would be used for research purposes only, which may include publication, and informed consent was then obtained.

Each student participated in a 1-hour, one-on-one, semistructured student interview, during which the 5 videos were played, in the same predetermined sequence. After each video, the RA asked each student what he or she would do next if s/he were the student in the scenario. Students were asked the specifics of what they would do (or say), and how they would do it. They were then encouraged to talk about what other options might exist for a student, and what they thought would happen next after any of the suggested actions. At the end of the interview, students were asked their opinions about whether they felt the videos were realistic and whether the issues they depicted seemed authentic.

By using 5 cases per student, a sample size of 20 students would yield 100 case-based interviews. Based on theoretical sampling and our previous experiences, this data set was expected to be sufficient to saturate the range of students' reasoning processes in relation to these 5 representative cases.10

ANALYSIS

A criterion sample of 19 students was initially enrolled.10 One interview was excluded when it was determined that the student was concurrently enrolled in law school, and was not actually part of the same cohort. This left 18 interviews for analysis (10 women, 8 men), for a total of 90 “units” (18 students × 5 scenarios each). Audiotapes were transcribed and rendered anonymous. Each interview produced 9 to 20 pages, for a total of 229 pages of textual material for analysis. Interviews were analyzed using grounded theory, which is a qualitative methodology used for developing explanatory models built on data gathered on a social or experiential phenomenon about which little is known (e.g., reasoning in the face of professional dilemmas). Three researchers read the transcripts independently in a constant comparative search for emergent themes.11 The group met repeatedly over an 8-month period to discuss and negotiate preliminary analyses. Consistent with an iterative tradition, data were analyzed from a number of perspectives: by student, by scenario, and by thematic category. Reasoning patterns were not consistent across videos for each student, and therefore we combined all student data for each video, and used the video as the perspective of analysis.

As thematic categories in the coding structure evolved, additional transcripts were analyzed to challenge, expand, and refine the categories. As the iterative analysis process continued alongside data collection, categories were further detailed and subdivided, or revised and deleted, as the coding structure developed. Once no further changes to the conceptual structure were forthcoming from the data, we determined that saturation had been reached, and therefore no further subjects need be recruited. The confirmed coding structure was then entered into NVivo qualitative data analysis software, version 2.0, (QSR International Pty Ltd., Melbourne, Australia) and applied to the entire data set by an RA, following intensive training in the codes and their definitions.12 The RA met frequently with a member of the research team to verify the appropriateness of the coding.

NVivo facilitates axial coding, whereby text may be cross-coded if it involves more than 1 category (e.g., if it involves more than 1 principle, or includes both a principle and an implication, etc.) Therefore, the sum of the units coded in all subcategories is greater than the total sum of units coded.

RESULTS

Students found the videos authentic and engaging, and with very few exceptions of specific videos for specific students, were able, for the most part, to “put themselves in the position” of the students depicted in the videos. This enabled them to discuss options for action fairly easily. Although a few students were slightly more resistant and less forthcoming than the others, we did obtain rich and varied discussion from almost all of the students. Although the semistructured interview included several questions as prompts for discussion, students' responses during the interviews did not follow a pattern of temporally self-contained responses to each question. Rather, the semistructured interview allowed for a more organic narrative to unfold in which students' responses are recursive, sometimes self-contradictory, and often revisionary. Therefore it was necessary to analyze the transcripts as a complex narrative, rather than as a set of simple survey responses.

Alternatives for Action

Initially, the data set was explored to determine what specific actions students suggested as being plausible alternatives for the student in the video. Although the videos theoretically might have provoked binary responses, in reality each student generated many options for action (mean = 3.81/student/scenario). For example, in video 1, the obvious options might be “tell her” or “don't tell her” the test results. However, our students actually provided many variations around the “don't tell her the results” option, which included suggestions to: tell her that the results are in but you need to discuss them with the team first; tell her to ask her other doctors; tell her that you know but can't tell her; or evade the question by asking her which tests, or why she wants to know. When summed across all students, a mean of 11.2 unique options were generated per scenario. That no single option was identified by every student in any of the scenarios indicates that the scenarios were sufficiently authentic to avoid students selecting a single “pat” or “idealized” right answer.

Motives for Considering Action

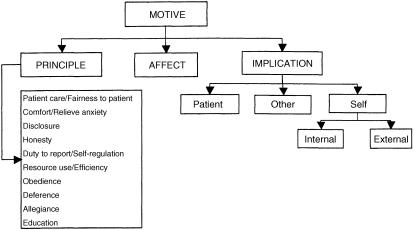

Although documenting the numbers and types of alternatives suggested by students is important, it does not explain why these actions were being considered. The majority of the analysis therefore focused not on the suggested actions themselves, but on students' apparent motives when suggesting particular courses of action. Specifically, we were interested in the reasons they gave for any action suggested, whether they were considering the action from their own point of view or from others'. As a group, students were motivated to consider actions by reference to a Principle, by reference to an Implication, or by reference to an Affect (see Fig. 1). All quotations are referenced by video number and by student (V#, S#).

Figure 1.

Representation of coding structure developed to capture students' reasoning strategies in response to the 5 videos.

Reference to Principles

An instance was coded as a Reference to Principle if the student made reference to an abstract or idealized concept in describing his/her reason(s) for suggesting an action. Many of these concepts are consistent with the standard principles described by professional bodies, for example, “Honesty is always the best policy” (Honesty) (V5, S17), or “It would be unfair to… patients” (Patient care/Fairness to patient) (V3, S13), or “The patient has a right to know” (Disclosure) (V1, S11). (See Table 1.) However, as illustrated in Table 1, there is a second list of principles that students also made reference to, for example: “…you probably want to do what your supervisor's going to say” (Obedience) (V1, S10); “The unwritten code being…‘I don't want to make my senior look bad'” (Allegiance) (V2, S14); or “…when it comes to duty, your first importance is you get an education…never miss your lectures, never miss teaching opportunities” (Education) (V3, S16). These two lists of principles are discussed further below.

Table 1.

Principles—Avowed and Unavowed—As Illustrated by Students' Quotes Obtained During Interviews

| Principle | Example from Interviews |

|---|---|

| “Avowed” principles | |

| Patient care/fairness to patient | “I think she deserves somebody who can really fully answer all her questions.” (V1, S14) |

| “I mean, the patient is your responsibility first.” (V3, S1) | |

| Comfort patient/relieve anxiety | “No, the patient's comfort would be the most important thing. I think with anything I do, even if it's—whatever, I try to make sure the patient's comfortable.” (V5, S5) |

| “I would feel obligated, morally obligated to just stay and…and comfort and support him.” (V3, S10) | |

| Disclosure | “The patient has a right to know.” (V1, S1) |

| “You have to remember that the patient is entitled to knowing exactly who is doing this, and their level of expertise.” (V5, S17) | |

| Honesty | “I find that honesty is always the best policy.” (V5, S17) |

| “Because we're really sort of encouraged not to lie to our patients. It's something that's sort of drummed in there.” (V3, S14) | |

| Duty to report/self-regulation | “…it's a question as to whether you're going to call the Royal College, or you're just going to talk to someone in your clerkship and say ‘Look, this isn't someone who's teaching us skills we want to emulate'…” (V4, S19) |

| “If things didn't change during the visit itself, I would go and tell the clerkship director …that this isn't…is completely inappropriate.” (V4, S1) | |

| Resource use/efficiency | “I think [it would result in] maximal gain in everything. The patient's care, the physician's time, my time…right….” (V2, S12) |

| “It's not unexpected to leave it for the next team…it's better to start—then if you can, handle it yourself to finish off the rotation.” (V2, S7) | |

| “Unavowed” principles | |

| Obedience | “I would probably—if it's been made very clear to me that the surgeon says drop it, I probably would not pursue it.” (V1, S17) |

| “It's not in my position to supersede the physician who is responsible for me.” (V1, S12) | |

| Deference | “It's really tempting to just defer to…well, you know—he must know what he's talking about.” (V2, S14) |

| “…he's the doc, he knows, right? Who am I, I'm just a student.” (V4, S12) | |

| Allegiance | “…sort of, the unwritten code being…I don't want to make my senior look bad.” (V2, S14) |

| “And your duty to the physician—sorry, to the patient, and to the team.” (V1, S17) | |

| Education | “…other students might just go along with it, cause ‘You're here for learning'….” (V4, S16) |

| “…when it comes to duty, your first importance is you get an education…never miss your lectures, never miss teaching opportunities. Like that's our first role.” (V5, S16) |

V, video number; S, student number.

Reference to Implications

In many instances, students' reasoning included a consideration of the potential implications, or consequences, of imagined actions. Students articulated implications for 3 main groups of individuals: Patients, Others (which included attending physicians, residents, and other team members), and Self (the student). (See Table 2 for examples of quotations.)

Table 2.

Potential Implications of Suggested Actions as Illustrated by Students' Quotes Obtained During Interviews

| Implications for: | Examples from Interviews |

|---|---|

| Patient | “I'm thinking, is the patient going to be comfortable? They may agree to let me do it, but are they going to sit there and are their muscles going to be tense and…I'm not going to be able to do the procedure well and I may harm the patient.” (V5, S10) |

| “Well if I go in as a clerk and say ‘You have a tumor,' and the staff hasn't told her…, then that's going to be detrimental to her trust in that relationship. She's going to be: ‘Oh, he sent in his clerk to tell me I have cancer,' like how horrible is that?” (V1, S11) | |

| Other | “I wouldn't want to do that first, because that might get my staff person in trouble….” (V1, S16) |

| “[You might] destroy a doctor's relationship with a patient, a family, another physician, God knows what else!” (V1, S19) | |

| “…to avoid conflict or discordance among members of the team. Because that…can diminish the group dynamics of the team.” (V2, S15) | |

| Self | |

| External | “It doesn't matter what the faculty says, you're the person who's going to get burned when it comes down to your final evaluation.” (V4, S3) |

| “You want to get good marks in clerkship so you can get the residency of your choice.” (V1, S10) | |

| “…it's a power thing…cause they're the resident,…you're going to have to work with him for another 3 weeks…[he] can make your life like heaven or can make your life hell.” (V3, S13) | |

| “I don't know if you want to get labeled a ‘professionalism watchdog' so early in your career.” (V1, S19) | |

| Internal | “I think I would have trouble sleeping if I told him a lie for the specific reason of me getting out of there faster.” (V3, S14) |

| “…cause if anything went wrong…I would not be able to completely absolve myself of the guilt.” (V2, S14) |

V, video number; S, student number.

The implications for patients largely centered around a concern that the patient would receive poor care, or would have an adverse health outcome as a result of a student's action (or failure to act), e.g., one student was concerned that “I may harm the patient” (V5, S10). Students were also concerned that an unprofessional action might lead to a patient's distrust in their physician or the health care system in general, which might have repercussions for their future health. In addition to considering implications for their patients, students also saw implications relating to other health care professionals, such as their attendings, or their resident or team. For example, one student was concerned that his/her actions might “destroy a doctor's relationship with a patient, a family, another physician, God knows what else!” (V1, S19).

Implications for self (i.e., the student) were the most frequent implications articulated by our students, especially in those scenarios that involved an attending physician or resident (e.g., V1, 2, and 4). These implications could be external, for example relating to concerns about evaluations or grades, e.g., “You're…going to get burned when it comes down to your final evaluation” (V4, S3). Students were also concerned about what might happen to their reputations, e.g., not wanting to risk being labeled as a “professionalism watchdog.” However, there were also potential internal implications for the students, including strong emotional reactions that might ensue, or “internal wars” or “struggles” if a particular action was (or was not) undertaken.

Reference to Affect

This code was created to capture those instances in which emotions, feelings, or instincts of students are what motivates them to consider specific actions. For example, “I couldn't see myself saying that, even though I know in my heart that that's what we should be doing” (V4, S10), or “I would just be acting on this gut feeling, like this is wrong” (V1, S19). These are not feelings that they would imagine experiencing as implications of undertaking a particular action, but what they would imagine feeling in the moment.

Because the 5 scenarios were chosen to highlight different professionalism dilemmas and conflicts for students, the ranges and types of principles and implications were different for each scenario (see Table 3). For example, 3 of the scenarios (V1, V2, and V4) depicted an attending physician or resident in a directive role, and these 3 videos provoked similar patterns of responses—specifically a predominance of implications for self compared with implications for the patient, more instances of affect, and a higher proportion of principles from the second list. This is discussed further below.

Table 3.

Summary of Students' Responses by Video

| Reasoning Around Actions | Video 1 n = 35 | Video 2 n = 54 | Video 3 n = 30 | Video 4 n = 23 | Video 5 n = 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference to Principles | |||||

| “Avowed” | |||||

| Pt care/fairness to pt | 10 | 10 | 16 | 4 | 3 |

| Comfort/relieve anxiety of pt | 4 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 14 |

| Disclosure | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Honesty | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 11 |

| Duty to report/self-regulation | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Resource/efficiency | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | 27 | 21 | 28 | 15 | 35 |

| “Unavowed” | |||||

| Obedience | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Deference | 6 | 19 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Allegiance | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | 1 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 5 |

| Subtotal | 18 | 35 | 12 | 12 | 7 |

| Reference to Affect | 10 | 14 | 5 | 14 | 6 |

| Reference to Implications | n = 33 | n = 24 | n = 13 | n = 32 | n = 23 |

| Self | 18 | 18 | 5 | 27 | 9 |

| Internal | 2 | 11 | 4 | 10 | 2 |

| External | 16 | 10 | 3 | 22 | 9 |

| Patient | 10 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 8 |

| Other | 10 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Alternatives for action | |||||

| Total number of acceptable actions | 17 | 10 | 9 | 13 | 9 |

| suggested by all students | |||||

| Mean number/student | 4.08 | 3.72 | 3.56 | 4.61 | 3.17 |

| Median number/student | 4.00 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 4.00 | 3.0 |

| Range/student | 2–8 | 2–7 | 3–7 | 2–6 | 2–6 |

Reasoning around actions includes those suggested actions which were accompanied by students' reasoning. Alternatives for action includes all actions suggested by students, whether reasons were provided or not. See Box 1 for description of videos.

Pt, patient.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to develop a deeper understanding of the reasoning processes that students engage in when describing how they might act in the face of professional dilemmas. The methodology used—videotaped scenarios reproducing actual events, with one-on-one, anonymous, facilitated interviews—allowed us to gain further insight into students'“real-time” reasoning strategies, and provided us with a window into what factors students weigh when reasoning through professional challenges.

It is clear in our data that students are often motivated to consider certain actions by referring to principles, such as honesty, disclosure, and fairness to patient/patient care. This list, as seen in Table 1, comprises the familiar principles and ideals that are standard to many definitions of professionalism, such as that set forth by the American Board of Internal Medicine.13 These are the classic principles that we as a profession avow—we declare them openly and proudly—and teach to our students.

Yet students also referred to several other principles, such as obedience or deference to an attending, or allegiance to one's team. These principles differ from those that are avowed. They are clearly recognized by students, they are legitimate, and they may even be crucial to success in the clerkship and in the profession. However, they are not avowed by the profession—they are not the type of principles that appear in formal documents or position papers about professionalism. However, these principles are not merely the antithesis of avowed principles, and thus are not explicitly disavowed either; that is, they are not actively discouraged, and may in fact be implicitly encouraged as a part of the hidden curriculum. Thus, these principles might best be considered “unavowed”: they are simply not discussed as part of our explicit professional or educational agenda. This may be, in part, because they do not project to the public the image of “the professional” that we wish to portray—an idealized image of an independent doctor looking after patients' interests, rather than a member of a team looking out for team or social interests.

In addition to being influenced by principles, students also frequently considered the potential implications of their actions for their patients or for others (e.g., team members). But students' suggested actions were most frequently accompanied by a consideration of the implications of those actions for themselves, especially in those scenarios in which an attending physician or resident was portrayed in a directive role (V1, V2, and V4). Students were looking out for their own interests, articulating concern about what would happen to their evaluations, grades, and reputations; they also worried that certain actions (e.g., lying) would cause them to lose sleep or feel tremendous guilt.

It is entirely acceptable, and indeed encouraged in medical education, to consider implications for a patient when deciding how to act. As in the earlier discussion regarding principles, these could be considered avowed implications. Also consistent with the earlier discussion, considering implications for others, such as one's attending physician or resident, might be considered unavowed (or unexpressed), although they are certainly recognized by students. In contrast, considering implications for oneself is actively disavowed by the profession—we explicitly deny, disclaim, or denounce being motivated by these influences. In fact, students are often taught that any consideration of themselves indicates selfishness, and is dangerously inconsistent with the ideal of altruism.

The concept of a “hidden curriculum” in medical education was first described by Hafferty and Franks and refers to the observations that many of the critical determinants of physician identity operate not within the formal curriculum but in a more subtle, less officially recognized “hidden” curriculum.14,15 Our data suggest that there is one further dimension of this hidden curriculum that requires attention—those elements that, rather than simply being hidden away from the formal curriculum, are actively disavowed or denied by the professional community. Indeed, these implications were often the predominant influence on students' reasoning.

These findings have implications for assessment and evaluation. It is clear that the students in our study were aware of the principles and implications that the profession avows, and would likely be able to reproduce these when asked. For example, in an examination setting, students know to “put the patient first,” to always focus on patient care and comfort as opposed to their own needs (including education), and if they considered any implications at all, they would focus on those concerning the patient. However, we would not obtain any insight into what our data suggest may be the most predominant influences on students' reasoning at this stage in their training—consideration of implications for themselves. This is important to understand and recognize when designing new methods of assessment.

Additionally, we need to recognize that when students consider acting in the face of professional dilemmas, they do so motivated by concern for 3 sorts of implications: avowed, unavowed, and disavowed. As educators, we must be willing to acknowledge the fact that these 3 levels of implications do, in fact, exist for students—and physicians —in situations such as those depicted in our videos, as well as in real life practice. It is unrealistic, and potentially dysfunctional for students' professional development, to ignore this truth. That students do consider themselves part of the equation should be neither alarming nor disappointing. It is instead promising, as it is an indicator of self-reflective reasoning.

Arguably, some acknowledgment and consideration of implications for oneself is vital for survival, but since this may be considered the antithesis of altruism, one can understand why the medical profession would disavow it. We do not have a good way of abstractly defining the limits of self-interest, and therefore, by allowing any discussion or acknowledgment of it, we are in danger of being on a slippery slope. However, as a group of educators and mentors, we should acknowledge what students themselves have recognized: that they are, at times, motivated by considering implications for themselves. Instead of invoking the principle of altruism and teaching students that such considerations are wrong, we should acknowledge these influences, and take the opportunity to teach students how to reason through and navigate these unavowed (and disavowed) principles and implications, in order to help them develop a balanced professional stance.9 The notion of altruism does not require turning a blind eye to implications for self—rather, it requires self-reflection and self-conscious rationalization.

This study was funded by the Medical Council of Canada. The funding agency had no role in design or conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold L. Assessing professional behaviour: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Acad Med. 2002;77:502–15. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginsburg SR, Regehr GR, Hatala R, et al. Context, conflict, and resolution: a new conceptual framework for evaluating professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75(10 suppl):S6–11. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200010001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christakis DA, Feudtner C. Ethics in a short white coat: the ethical dilemmas that medical students confront. Acad Med. 1993;68:249–54. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin DC, Daugherty SR, Rowley BD. Unethical and unprofessional conduct observed by residents during their first year of training. Acad Med. 1998;73:1195–200. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199811000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satterwhite RC, Satterwhite WM, III, Enarson C. An ethical paradox: the effect of unethical conduct on medical students' values. J Med Ethics. 2000;26:462–5. doi: 10.1136/jme.26.6.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hicks L, Lin Y, Robertson DW, Robinson DL, Woodward SI. Understanding the clinical dilemmas that shape medical students' ethical development: a questionnaire survey and focus group study. BMJ. 2001;322:709–10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7288.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginsburg SR, Regehr G, Lingard L. The anatomy of the professional lapse: bridging the gap between traditional frameworks and students' perceptions. Acad Med. 2002;77:516–22. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lingard L, Garwood K, Szauter K, Stern DT. The rhetoric of rationalization: how students grapple with professional dilemmas. Acad Med. 2001;76(10 suppl):S45–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200110001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginsburg SR, Regehr G, Lingard L. To be and not to be: the paradox of the emerging professional stance. Med Educ. 2003;37:350–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. 1st edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaser BG. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelle U. Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis: Theory, Methods, and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Project Professionalism. American Board of Internal Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: American Board of Internal Medicine; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69:861–71. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stern DT. Practicing what we preach? An analysis of the curriculum of values in medical education. Am J Med. 1998;104:569–75. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]