Abstract

Expression of the Norwalk virus open reading frame 3 (ORF3) in Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells yields two major forms, the predicted 23,000-molecular-weight (23K) form and a larger 35K form. The 23K form is able to interact with the ORF2 capsid protein and be incorporated into virus-like particles. In this paper, we provide mass spectrometry evidence that both the 23K and 35K forms are composed only of the ORF3 protein. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and phosphatase treatment showed that the 35K form results solely from phosphorylation and that the 35K band is composed of several different phosphorylated forms with distinct isoelectric points. Furthermore, we analyzed deletion and point mutants of the ORF3 protein. Mutants that lacked the C-terminal 33 amino acids (ORF31-179, ORF31-152, and ORF31-107) no longer produced the 35K form. An N-terminal truncation mutant (ORF351-212) and a site-directed mutant (ORF3T201V) were capable of producing the larger form, which was converted to the smaller form by treatment with protein phosphatase. These data suggest that the region between amino acids 180 and 212 is phosphorylated, and mass spectrometry showed that amino acids Arg196 to Arg211 are not phosphorylated; thus, phosphorylation of the serine-threonine-rich region from Thr181 to Ser193 must be involved in the generation of the 35K form. Studies of the interaction between the ORF2 protein and full-length and mutated ORF3 proteins showed that the full-length ORF3 protein (ORF3FL), ORF31-179, ORF31-152, and ORF351-212 interacted with the ORF2 protein, while an ORF31-107 protein did not. These results indicate that the region of the ORF3 protein between amino acids 108 and 152 is responsible for interaction with the ORF2 protein.

Norwalk virus (NV) is the prototype strain of the Norovirus genus in the family Caliciviridae (24). The noroviruses are a group of viruses that are the major pathogens causing epidemic nonbacterial gastroenteritis (8, 31). The NV genome is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA molecule approximately 7.7 kb in length predicted to encode three open reading frames (ORFs) (16, 18). The first ORF (ORF1) encodes the nonstructural proteins. The second ORF (ORF2) encodes the capsid protein. Expression of the capsid protein in insect cells infected with baculovirus recombinants results in the self assembly of empty recombinant virus-like particles (rVLPs) (17, 32). The third ORF (ORF3) is located at the 3′ end of the genome and codes for a 212-amino-acid protein that has been characterized as a minor structural protein (9). Expression of the NV ORF3 region in insect cells yields two forms of ORF3 protein, a 23,000-molecular-weight (23K) unphosphorylated form and a 35K phosphorylated form (9). While the ORF3 protein is not essential for the formation of empty VLPs (10, 13, 17, 21, 32), the ORF3 23K protein is associated with recombinant NV (rNV) VLPs purified from insect cell cultures infected either with a baculovirus recombinant expressing the entire 3′ end of the genome or by coinfection with baculovirus recombinants that individually express the ORF2 and ORF3 proteins (9).

Protein expression and interaction studies of the human caliciviruses remain limited due to the lack of a tissue culture system for virus propagation. Conservation of ORF3 in all caliciviruses suggests that it performs an important function in the virus life cycle. The ORF3 protein is present in feline calicivirus (FCV) and rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) particles (22, 29). However, no studies have examined the potential domains present in the ORF3 protein. In this paper, we report domains of the ORF3 protein responsible for formation of the larger 35K form and for ORF3 protein-capsid protein interaction. In addition, we report further characterization of the 35K form. These studies were facilitated by the generation of baculovirus recombinants that express mutant ORF3 proteins in insect cells and ORF3-specific peptide antisera. The baculovirus recombinants were also coinfected with an ORF2 baculovirus recombinant to examine the ability of the ORF3 mutant proteins to interact with the ORF2 protein allowing incorporation into rNV VLPs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and recombinant baculoviruses.

For N-terminal HA-tagged ORF3, the hemagglutinin (HA) tag was cloned onto the N terminus of the ORF3 protein by PCR amplification using primers p119HAst (5′-GATCGGATCCATGTACCCGTACGACGTGCCGGACTACGCAGTGGCCCAAGCCATAATTG-3′; nucleotides [nt] 6950 to 6968 [BamHI site underlined, start site in boldface type, HA tag underlined, and Met-to-Val change in italic type) and NV3′end (5′-GATCCTCGAGAACATCAAATTAAACCTAATTAAACC-3′; nt 7654 to 7628 [XhoI site underlined]) in a standard PCR using pNVEco3 as a template (16). The amplified fragment was cloned directly into the pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) following the manufacturer's protocol to generate pCRII-NHAORF3. The NHA-ORF3 fragment was subcloned from pCRII-NHAORF3 by restriction enzyme digestion with BamHI and EcoRI. The fragment was purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and ligated into the pVL1393 vector digested with the same enzymes to generate pVL-NHAORF3. Baculovirus recombinant BacNHANV3 (ORF3NHA) was generated as previously described (17).

ORF3 C-terminal deletion mutants.

The ORF3-containing plasmid pG7BamNV3 was used for the generation of C-terminal deletion mutants of ORF3. Restriction enzyme digestion of the pG7BamNV3 plasmid with AvaI resulted in the excision of a 347-bp fragment. The vector containing nt 6950 to 7272 of ORF3 was gel purified and ligated to generate pG7NV31-107. The pG7BamNV3 plasmid was double-restriction-enzyme digested with SpeI and XbaI, resulting in the excision of a 212-bp fragment. The vector fragment containing nt 6950 to 7407 was gel purified and ligated to generate pG7NV31-152. Double-restriction-enzyme digestion of pG7BamNV3 with HincII and XbaI resulted in the excision of a 130-bp fragment. The vector fragment, containing nt 6950 to 7489, was gel purified and ligated to generate pG7NV31-179. The mutant ORF3 fragments were subcloned into the pVL1393 baculovirus transfer vector for the generation of pVLNV31-107, pVLNV31-152, and pVLNV31-179. BacNV3 (full-length ORF3 [ORF3FL]) was generated previously (9). Recombinant baculoviruses BacNV31-179 (ORF31-179), BacNV31-152 (ORF31-152), and BacNV31-107 (ORF31-107) were generated as described previously (17).

ORF3 N-terminal deletion mutant.

An N-terminal deletion mutant of ORF3 was generated by PCR amplification from an in-frame ATG codon in the ORF3 coding region at nt position 7103 by using pG7BamNV3 as a template. The region of ORF3 beginning with nt 7103 was PCR amplified by using primers pATG7103 (5′-GATCGGATCCGCATGATTGGGTATCAGGTTGAA-3′; nt 7103 to 7123 [BamHI site underlined and start site in boldface type]) and p120 (5′-GCGCCGCGCTCGAGAATATGATGCCCACATTTC-3′; nt 7619 to 7600 [XhoI site underlined]). The PCR product was cloned directly into the pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) for the generation of pCRIIORF351-212. The N-terminal deletion mutant fragment was subcloned into the pVL1393 baculovirus transfer vector to produce pVLNV351-212. Recombinant baculovirus BacNV351-212 (ORF351-212) was generated as described previously (17).

Site-directed mutagenesis of ORF3.

Threonine at amino acid position 201 was changed to a valine by using a QuikChange kit (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, Tex.) following the manufacturer's protocol. The mutation was incorporated into ORF3 by generating primers with the mutation as well as a unique restriction site to allow for screening. pCRTOPO-ORF3+3′NCR was programmed into a PCR with primers ORF3sdmF (5′-CTCAATACAGTGTGGTTGGTGCCACCCGGGTCAACAGCC-3′; nt 7472 to 7510 [T201V in boldface type and the SmaI site underlined]) and ORF3sdmR (5′-GGCTGTTGACCCGGGTGGCACCAACCACACTGTATTGCG-3′; nt 7510 to 7472 [T201V in boldface type and SmaI site underlined]). The reaction was treated with DpnI to remove the template and subsequently transformed into XL1-Blue cells (Stratagene) following the manufacturer's protocol. Colonies were screened by plasmid purification and restriction enzyme digestion with EcoRI and SmaI. The mutant fragment was subcloned into the pVL1393 baculovirus transfer vector to produce pVLNV3T201V. Sequencing was done to ensure authenticity of pVLNV3T201V. Recombinant baculovirus BacNV3T201V (ORF3T201V) was generated as described previously (17).

Expression of ORF3 in insect cells.

Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells were infected with the full-length ORF3 or ORF3 mutant baculovirus recombinants at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 PFU/cell. At 65 h postinfection (hpi), the cells were lysed in 5× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer (1% SDS, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.05 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.6 to 6.8], 10% glycerol, 0.0025% phenol red). An aliquot equivalent to 3 × 105 cells was separated by electrophoresis in an SDS-15 or 18% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for Western blot analysis that was performed by using a mixture of both the ORF3 N-terminal and C-terminal peptide antisera, each at a dilution of 1:1,000, followed by horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G [IgG]; 1:5,000 dilution; Cappel, West Chester, Pa.), with detection by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) as previously described (4).

Phosphatase treatment of ORF3 proteins.

Semipurified ORF3 proteins were used for phosphatase treatment experiments. Insect cells (6 × 107) in a T-150 flask were infected with the ORF3NHA, ORF351-212, or ORF3T201V baculovirus recombinant at a MOI of 10. At 72 hpi, the infected cells were harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and lysed in 1 ml of 1 M CHES(2-[N-cyclohexylamino]ethane sulfonic acid)-1% CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate} (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) for 10 min at room temperature (RT). The lysates were clarified by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge (IEC Micromax, Neeham Heights, Mass.) for 10 min at 15,000 rpm, and each pellet was suspended in 1 ml of 2% CHAPS for 10 min at RT. The suspension was centrifuged again in the same manner, and each pellet was suspended in 250 μl of 8 M urea-4% CHAPS and incubated for 10 min at 80°C. The heated suspensions were centrifuged a third time, and the supernatants that contained the OFR3 proteins were collected. The ORF3 protein samples were dialyzed exhaustively against 50 mM NH4HCO3. The dialyzed samples were treated with either calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP; Gibco-Life Technologies) or protein phosphatase 1 (PP1; New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). An aliquot of the samples (between 5 and 18 μl depending on the level of protein expression) was adjusted to 20 μl of 1× dephosphorylation buffer and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in the absence or presence of enzyme (CIP, 2.5 U/20 μl; PP1, 2.5 U/20 μl). All samples were analyzed by SDS-15% PAGE followed by Western blotting using a mixture of both the ORF3 N-terminal and C-terminal peptide antisera (1:1,000 dilution) as the primary antibody. Alkaline phosphatase (AP)-labeled secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG; 1:5,000 dilution; Sigma) and the substrate 5-bromo-4 chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP)-nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) (Sigma) were used to visualize the ORF3 proteins.

Two-dimensional (2D) gel analysis of ORF3NHA and ORF31-179 proteins.

Semipurified ORF3 proteins were used for 2D gel analysis. Insect cells in T-150 flasks were infected with the ORF3NHA or ORF31-179 baculovirus recombinant at a MOI of 10. The ORF3 proteins were semipurified by using a procedure similar to that used for phosphatase treatment (see above), except without dialysis. ORF3NHA or ORF31-179 protein in 8 M urea-4% CHAPS solution was used for isoelectric focusing (IEF). CIP-dephosphorylated ORF3NHA protein for 2D gel analysis was obtained as described above; then, the dephosphorylated sample was adjusted to 8 M urea-4% CHAPS. The first-dimension IEF was performed on a precast immobilized pH gradient gel (IPG ReadyStrip; pH 3 to 10; 11 cm; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) with a Bio-Rad protein IEF cell following the manufacturer's instructions. The second dimension of separation was done by SDS-15% PAGE followed by Western blot analyses using a mixture of both the ORF3 N-terminal and C-terminal peptide antisera (1:1,000 dilution) and visualization with an AP-labeled secondary antibody and the BCIP-NBT substrate as described above.

Coimmunoprecipitation of the ORF2 and ORF3 proteins from infected insect cells.

Sf9 cells were dually infected with full-length Bac-NV2 or a capsid protein mutant lacking the N-terminal 20 amino acids (2) and with full-length Bac-NV3 or mutants, each at a MOI of 5. Cultures were harvested 65 hpi in native buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.2], 1% Trasylol). The lysates were collected, clarified, and preabsorbed with Staph A protein. An aliquot (3 × 106 cells in 500 μl) was mixed with a capsid monoclonal antibody, mAb 8812, at a dilution of 1:60 and incubated overnight at 4°C. Immune complexes were precipitated with Staph A protein by incubating them for 2 h on ice. After the precipitated complexes were washed three times with native buffer, the samples were suspended in 5× SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled, the Staph A was pelleted, and half of the sample was loaded for detection by Western blot analysis using both the ORF3 N-terminal and C-terminal peptide antisera (1:1,000 dilution).

Western blot analysis to detect ORF3 protein in preparations of rNV VLPs.

The ability of the ORF3 protein to be incorporated into rNV VLPs when ORF2 and ORF3 were expressed from different baculovirus recombinants has been previously reported (9). Western blot analysis was used to examine the incorporation of the mutant ORF3 proteins into VLPs. Sf9 cells were dually infected with full-length Bac-NV2 and Bac-NV3 or mutants, each at a MOI of 5. Cultures were incubated for 6 days in the presence of protease inhibitors (0.5 μg of aprotinin/ml [Sigma], 0.7 μg of pepstatin/ml [Calbiochem], and 0.5 μg of leupeptin/ml [Sigma]). VLPs were harvested as described previously (9). Briefly, the dual-infection VLPs were concentrated by ultracentrifugation for 3 h at 122,300 × g and banded by rate-zonal centrifugation on a discontinuous 10 to 60% (wt/vol) sucrose gradient for 1 h at 120,000 × g. The VLP-containing fractions were pooled and concentrated by ultracentrifugation for 3 h at 122,300 × g. The purified VLPs (10 μg) were examined by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie blue R-250 staining, and Western blot analysis. The ORF3 protein was detected by using both ORF3 peptide antisera, each at a dilution of 1:1,000. Protein concentrations were determined by using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). The integrity of particles was confirmed by 1% ammonium molybdate staining and transmission electron microscopy.

Purification and sequence analysis of the 23K and 35K forms of ORF3 protein.

Sf9 cells (1.5 × 109) infected with the ORF3NHA baculovirus recombinant at a MOI of 10 were maintained in Grace’s supplemented insect medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 5 to 6 days at 27°C until the viability was ∼35%. Harvested cells were washed twice with PBS at RT, and the cell pellet was homogenized by using a 40-ml Wheaton 357546 Dounce tissue grinder (Wheaton, Millville, N.J.) in 40 ml of 2.0% CHAPS (Sigma) in PBS for 10 min at RT. After centrifugation for 10 min at 23,000 × g in a Beckman centrifuge, the supernatant (S1) which lacked the ORF3NHA protein was discarded. The pellet was further extracted for 10 min at 80°C by using a Wheaton tissue Dounce homogenizer in 20 ml of 1.5% CHAPS in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, preheated to 80°C. After a second centrifugation, the supernatant (S2) was discarded and the ORF3NHA protein in the pellet was repeatedly extracted at 80°C in the same way. Supernatants S3, S4, and S5, which contained the ORF3NHA protein, were collected and pooled, and ampholytes (pH 3 to 5; Bio-Rad) were added to achieve a final concentration of 1%. Proteins with various isoelectric points (pIs) were separated by IEF using a Bio-Rad 60-ml standard Rotofor chamber at a constant power of 15 W. The anode and cathode electrolytes were 0.5 M acetic acid and 0.25 M HEPES, respectively. The fractions containing proteins with pIs between 4.5 and 4.8 were pooled and refocused by using a Bio-Rad 18-ml mini Rotofor chamber at a constant power of 12 W with 0.5% ampholytes (pH range, 3 to 5) as described above. The fractions with pIs of 4.5 to 4.8 were pooled, dialyzed exhaustively against 50 mM NH4HCO3, and lyophilized.

The lyophilized proteins within pIs of 4.5 to 4.8 were resolved by SDS-18% PAGE and stained with 0.05% Coomassie blue R-250. The stained bands were cut out from the gel, digested with trypsin, desalted on a Zip Tip C18 column, and analyzed by using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Protein Chemistry Core Laboratory, Baylor College of Medicine).

RESULTS

Mapping the domain of ORF3 involved in the production of the larger 35K form of the ORF3 protein.

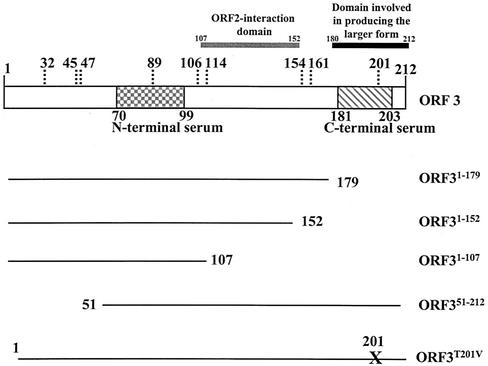

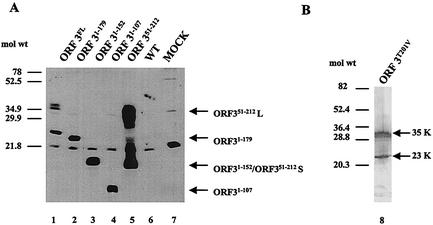

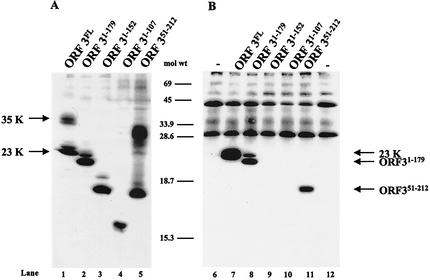

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the full-length ORF3 protein and the mutants generated for studies to map the domain of this protein involved in forming the 35K form. First, we examined protein expression in insect cells infected with full-length and mutant ORF3 baculovirus recombinants. The ORF3 protein was detected by Western blot analysis using a mixture of both the ORF3 N-terminal and C-terminal peptide antisera. All mutants expressed an ORF3 protein (Fig. 2). However, not all mutants expressed two forms of the ORF3 protein. The ORF31-179 mutant that lacks amino acids 180 to 212 was unable to make the larger form of the ORF3 protein; instead, a protein of approximately 22K, close to the predicted size of this mutant, was produced (Fig. 2A, lane 2). The same result was obtained for each of the C-terminal mutants. ORF31-152 and ORF31-107 each produced only a single band, which migrated close to the predicted size (approximately 17K and 12K, respectively) of each mutant (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4). The N-terminal mutant, ORF351-212, which contains amino acids 51 to 212, was capable of producing several forms of the ORF3 protein (Fig. 2A, lane 5). The smallest form migrated slightly faster than the expected size (18K) of this protein, and the larger forms migrated between 24K and 35K. These data suggested that the C-terminal 32 amino acids, from amino acids 180 to 212, are important for the production of the larger form of the ORF3 protein.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the ORF3 mutants. Shown are the proteins of full-length ORF3 (ORF3FL), the three C-terminal mutants (ORF31-179, ORF31-152, and ORF31-107), the one N-terminal mutant (ORF351-212), and the one site-directed mutant (ORF3T201V) generated for these studies. The positions of the N-terminal and C-terminal peptides to which antisera were produced are indicated. The amino acid positions, indicated with vertical dotted lines, designate Prosite pattern search-predicted sites of phosphorylation within the ORF3 protein. The domains mapped in this paper are also indicated.

FIG. 2.

Expression of the full-length and mutant ORF3 proteins in infected insect cells. (A) Sf9 cells were either mock infected (MOCK) or infected with wild-type baculovirus (WT), full-length ORF3 (ORF3FL), or the ORF31-179, ORF31-152, ORF31-107, or ORF351-212 baculovirus recombinant. (B) Sf9 cells were infected with the ORF3T201V baculovirus recombinant. Cells were harvested 65 hpi by lysis in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The samples were separated by SDS-18% PAGE (A) or SDS-15% PAGE (B), and Western blot analysis was performed by using both the ORF3 N-terminal and C-terminal peptide antisera at a dilution of 1:1,000 followed by horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG, with detection by enhanced chemiluminescence. ORF351-212 S, smaller form of the ORF351-212 protein.

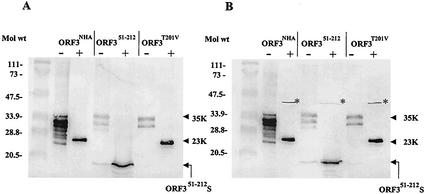

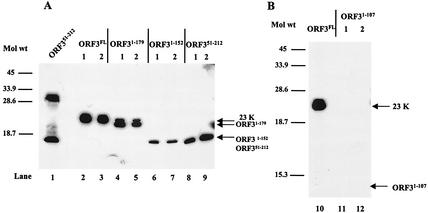

Previous work had shown that the migration of the 35K form is modified by phosphatase treatment (9). We hypothesized that the larger form was phosphorylation dependent, although the shift in apparent molecular weight seemed to be too large to be due simply to phosphorylation. A Prosite pattern search of the ORF3 protein revealed one site of predicted phosphorylation within the C-terminal 33 amino acids at position 201. Sequence alignment analysis revealed that this potential site of phosphorylation is conserved among the noroviruses. The site is a predicted protein kinase C phosphorylation site with the amino acid sequence TDR. To examine whether this predicted site of phosphorylation was important for the formation of the 35K form, the threonine at amino acid position 201 was mutated to a valine (ORF3T201V). The ORF3T201V mutant expressed in insect cells produced both forms of the ORF3 protein (Fig. 2B). This result indicated that the predicted site of phosphorylation at amino acid 201 was not critical for the formation of the 35K form of the ORF3 protein. To further examine whether phosphorylation was important for the generation of the larger form of the mutant ORF3 proteins, semipurified ORF3 proteins were incubated in the absence or presence of CIP or PP1. These analyses showed that treatment with CIP or PP1 resulted in the complete loss of detection of the larger forms of the ORF3 protein when three different constructs were used (Fig. 3). These data indicated that phosphorylation of residues other than T201 was important in the production of the larger form of the ORF3 protein.

FIG. 3.

Phosphatase treatment of the three constructs of ORF3 proteins. (A) Treatment of the ORF3 constructs with CIP (2.5 U/20 μl). (B) Treatment of the ORF3 constructs with PP1 (2.5 U/20 μl). Sf9 cells were infected with the N-terminal HA-tagged ORF3 (ORF3NHA), ORF3 N-terminal deletion mutant (ORF351-212), or ORF3 site-directed mutant (ORF3T201V), and the proteins in the cells were harvested 72 hpi and semipurified by extraction with 8 M urea-4% CHAPS. After dialysis against 50 mM NH4HCO3, an aliquot of these samples was incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of CIP or PP1. Treated samples were separated by SDS-15% PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose, and Western blot analysis was performed by using a mixture of the ORF3 N-terminal and C-terminal peptide antisera, each at a dilution of 1:1,000. The ORF3 proteins were visualized with AP-conjugated secondary antibody and the BCIP-NBT substrate. ORF351-212 S, smaller form of the ORF351-212 protein. The asterisks in panel B show that PP1 itself reacts and is detected directly by the BCIP-NBT substrate.

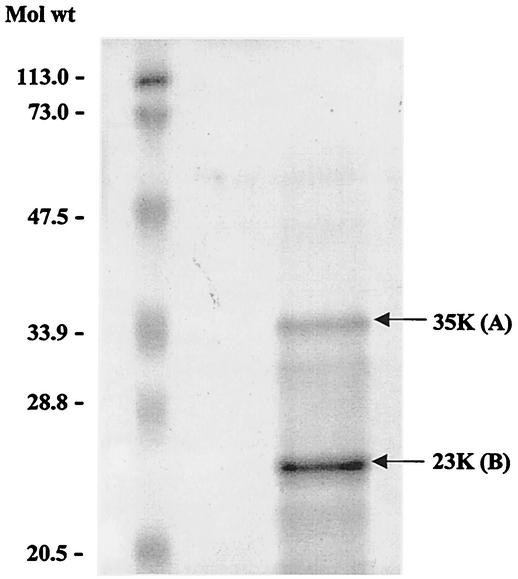

To determine whether the 35K form of the ORF3 protein was composed only of phosphorylated ORF3 or whether it might be an oligomer produced by interaction with other cellular proteins, we purified and analyzed both the 23K and 35K proteins by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The 35K form of the ORF3 protein was cell associated, and successful purification required extensive extraction with the detergent CHAPS followed by preparative IEF. A range of pIs was observed for the 35K form of the protein, consistent with its being phosphorylated; the majority of the protein bands showed pIs between 4.5 and 4.8 (see below). The 35K and 23K ORF3-related bands were separated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4), and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry showed that both bands contained only peptides from the ORF3 protein. Mass spectrometry confirmed that 10 peptide fragments of the trypsinized 35K band A shown in Fig. 4 matched sequences from the ORF3FL protein only, with sequences Arg34 to Asn67, Arg76 to Gln131, and Arg196 to Arg212 being identified. This showed that the 35K protein was composed only of a single protein and was not complexed with a heterologous protein. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry also confirmed that nine peptides of the 23K band B shown in Fig. 4 matched the ORF3FL protein, with the sequences Arg34 to His48, Arg76 to Ser88, Arg96 to Phe164, and Arg196 to Arg212 being identified. This identified the 23K protein as being ORF3 based on sequence identification of 53.7% of the protein sequence. No phosphorylated peptides were identified for the 35K protein. However, sequence information was obtained from Arg196 to Arg212 within the domain comprising amino acids 180 to 212 identified above as being involved in the formation of the larger form of ORF3; this localized the phosphorylated site(s) within amino acids 180 to 195.

FIG. 4.

Purified 23K and 35K forms of the ORF3 protein. Sf9 cells were infected with ORF3NHA baculovirus recombinant. The ORF3NHA protein was purified by extraction with 1.5% CHAPS and preparative IEF with a Bio-Rad Rotofor. The purified ORF3NHA protein was resolved by SDS-18% PAGE and Coomassie blue R-250 staining. 35K band A and 23K band B were sequenced by using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

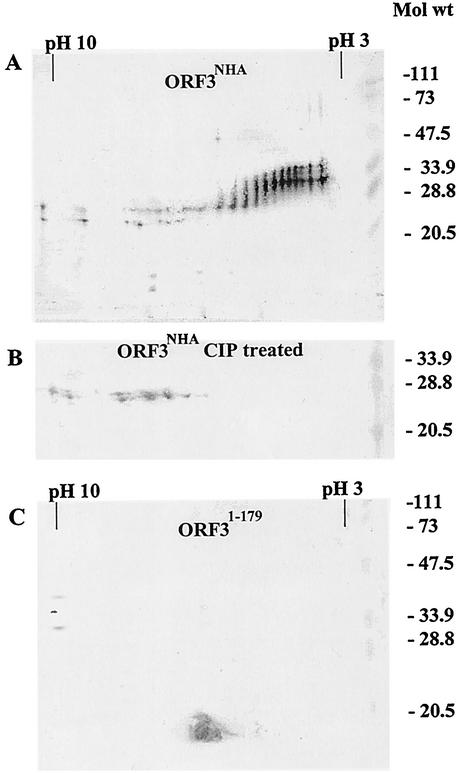

To identify the putative phosphorylated peptide, the behaviors of the ORF3NHA and ORF31-179 proteins were compared by 2D gel analysis. The ORF3NHA protein (Fig. 3) (prior to CIP and PP1 treatment) appeared as multiple bands with pIs between pH 3 and 10 and several forms between 23K and 35K (Fig. 5A). All of the larger forms of ORF3 had acidic pIs. The appearance of multiple bands with acidic pIs was also seen when the 35K forms of the ORF3T201V, ORFFL, and ORF351-212 proteins were analyzed (data not shown). Dephosphorylation of ORF3NHA (Fig. 3) (after CIP and PP1 treatment) resulted in the loss of all forms with acidic pIs together with the larger forms (Fig. 5B). The ORF31-179 protein separated as only one band with a pI of ∼6.5 migrating at its predicted mutant size with no larger form (Fig. 5C). Thus, the ORF31-179 protein, lacking amino acids 180 to 212 from the C terminus of the ORF3FL protein, and dephosphorylated ORF3NHA did not contain any bands with acidic pIs that represented phosphorylated protein. These results were consistent with the idea that there are multiple phosphorylation sites in the ORF3 protein that map between amino acids 180 and 212.

FIG. 5.

2D gel electrophoretic analysis of ORF3 proteins prior to and after phosphatase treatment. (A) ORF3NHA protein prior to CIP treatment. (B) ORF3NHA protein after CIP treatment. (C) Mutant ORF31-179 protein lacking C-terminal amino acids 180 to 212. Sf9 cells were infected with ORF3NHA or ORF31-179 baculovirus recombinant. ORF3 proteins expressed in insect cells were semipurified as outlined in Materials and Methods. The semipurified ORF3 proteins were analyzed by 2D gel electrophoresis, with the proteins being separated first by IEF on a pH 3 to 10 gradient gel, followed by separation in a second dimension on an SDS-15% polyacrylamide gel and detection of protein by Western blotting. Western blot analysis was performed by using a mixture of N-terminal and C-terminal peptide rabbit antisera and visualization with AP-conjugated secondary antibody and the BCIP-NBT substrate.

Mapping the domain of ORF3 involved in ORF3 protein-capsid protein interactions.

Next, we examined the ORF3 protein-capsid protein interactions by first analyzing complexes in insect cells dually infected with baculovirus recombinants that express full-length ORF2 (data not shown) (9) or an ORF2 mutant lacking the first 20 amino acids (ORF2NT20) and full-length or mutant ORF3 proteins (Fig. 6). Coinfected lysates of all ORF3 recombinants with ORF2NT20 recombinant showed that all ORF3 proteins were expressed well (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 to 5). These lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with a monoclonal antibody specific for the capsid protein, followed by Western blot analysis for the detection of the ORF3 protein (Fig. 6B). This analysis showed that the 23K form of the ORF3 protein interacted with the ORF2 protein as expected (data not shown) (9) and with the ORF2NT20 protein (Fig. 6B, lane 7). The 35K form of the ORF3 protein was not expected to interact with the ORF2 protein based on previously published dual-infection studies (9). The ORF31-179 protein interacted with the ORF2NT20 protein (Fig. 6B, lane 8). The two other C-terminal mutants, ORF31-152 and ORF31-107 proteins, did not interact with the capsid protein, while the mutant ORF351-212 protein was able to interact with the ORF2NT20 protein (Fig. 6B, lanes 9 to 11). No corresponding protein was detected in cells expressing ORF2 alone (Fig. 6B, lanes 6 and 12). Identical results were obtained after dual infection of insect cells with the full-length ORF2 protein instead of the ORF2NT20 protein (data not shown). This analysis showed that the larger forms of both full-length ORF3 and ORF351-212 proteins failed to interact with the ORF2 or ORF2NT20 protein. Additionally, these data indicated that the ORF3 protein does not interact with the first 20 amino acids of the ORF2 protein.

FIG. 6.

Coimmunoprecipitation of the ORF3 protein with the ORF2NT20 capsid protein mutant. Sf9 cells were coinfected with the ORF2NT20 mutant baculovirus recombinant and full-length or mutant ORF3 baculovirus recombinant. Cells were harvested 65 hpi by lysis in native buffer. (A) Lysate samples, prior to immunoprecipitation, were separated directly by SDS-18% PAGE. (B) Lysate samples were immunoprecipitated by using a capsid monoclonal antibody (mAb 8812) and separated by SDS-18% PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed by using the ORF3 N-terminal and C-terminal peptide antisera at a 1:1,000 dilution. The lanes designated with a dash indicate insect cells infected with the ORF2 baculovirus recombinant only.

To further confirm these results, we examined which of the mutant ORF3 proteins could be incorporated into purified VLPs. VLPs were purified through a sucrose gradient to separate proteins in VLPs from soluble protein. Western blot analysis of sucrose gradient-purified VLPs from insect cell cultures dually infected with the ORF2 and separate ORF3 (ORF31-179, ORF31-152, ORF31-107, or ORF351-212) baculovirus recombinants revealed that all of the ORF3 mutant proteins, except the ORF31-107 protein, interacted with the ORF2 protein (Fig. 7). Unexpectedly, the ORF31-152 protein did interact with the ORF2 protein in VLPs, although this interaction appeared to be at lower levels than that observed with the other mutant proteins (Fig. 7A, lanes 6 and 7). This interaction, which was not seen by coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 6B, lane 9) was most likely detected in the VLPs due to the increased sensitivity of this assay. Taken together, these data suggest that the region of the ORF3 protein between amino acids 108 and 152 contains the ORF2 interaction domain.

FIG. 7.

Western blot analysis of dual-infection VLPs by using the ORF3 peptide antisera. VLPs were purified from insect cell cultures infected with the full-length ORF2 baculovirus recombinant and the full-length or mutant ORF3 baculovirus recombinant. (A) VLPs isolated from cell cultures dually infected with the ORF2 and the ORF3FL, ORF31-179, ORF31-152, or ORF351-212 baculovirus recombinants. Shown in lane 1, designated ORF351-212, is a lysate sample from insect cells infected with the ORF351-212 mutant that produces the two forms of the ORF351-212 protein. (B) VLPs isolated from cell cultures dually infected with the ORF2 and the ORF3FL or ORF31-107 baculovirus recombinants. Purified VLPs were separated by SDS-18% PAGE, and Western blot analysis was performed by using the ORF3 N-terminal and C-terminal peptide antisera at a dilution of 1:1,000. Two separate gradient-purified preparations were analyzed (designated 1 and 2).

DISCUSSION

Protein expression and interaction studies of the human caliciviruses remain limited due to the lack of a tissue culture system for virus propagation. The establishment of the baculovirus system for the expression of NV proteins has expanded study of the human caliciviruses (17). Baculovirus recombinants expressing either ORF2 alone or ORF2 and ORF3 are able to produce rNV VLPs, indicating that the ORF3 protein is not essential for the formation of empty VLPs (10, 13, 17, 21, 32). However, conservation of ORF3 in all caliciviruses suggests that it performs an unknown important function(s) in the virus life cycle.

In an earlier study, we showed that expression of ORF3 alone results in the detection of two major forms, 23K and 35K, of the ORF3 protein. Further experiments indicated that the 35K form of the ORF3 protein is phosphorylated in insect cells (9). To further characterize the 35K protein and to dissect the domain required for production of the 35K form of the ORF3 protein, deletion mutants were constructed and examined for expression of the ORF3 protein. Mutated ORF3 proteins ORF31-107, ORF31-152, and ORF31-179, lacking the C-terminal 33 amino acids, do not produce the larger form. In contrast, an N-terminal deletion mutant, the ORF351-212 protein, containing the C-terminal 33 amino acids, does produce the larger form. These results localized amino acids 180 to 212 as being involved in the formation of the larger form.

A key question concerned the composition of the larger form of the phosphorylated ORF3 protein. Was this solely phosphorylated ORF3 protein, or was it a heterooligomer complexed with an unknown cellular protein? Analysis of the 35K form by 2D gel electrophoresis showed that the larger form of the ORF3NHA protein consisted of multiple ORF3-related protein bands with different acidic pIs as well as bands with more alkaline pIs. This was the first indication that the 35K form of the protein might be formed solely by phosphorylation, and phosphorylation might occur on multiple sites in the protein. 2D gel analyses also showed that the dephosphorylated ORF3NHA protein and the mutant ORF31-179 protein lacked the larger forms with acidic pIs, indicating that the phosphorylated forms of the protein had acidic pIs, as would be expected. These results confirmed that the region between amino acids 180 and 212 mediated the formation of the larger form of the ORF3 protein. In addition, these studies showed that phosphorylation, probably at multiple sites within this region, was the direct cause of the alteration of the migration of the ORF3 protein from the 23K to the larger 35K form, resulting in multiple bands with a range of alkaline to acidic pIs.

Previously, studies to characterize the larger form of the ORF3 protein have been hampered by the inability to purify this protein. Previous attempts in our laboratory to purify the ORF3 protein from constructs expressed in bacteria with several different tags were not successful because in all cases the fusion proteins were insoluble (unpublished data). The only antisera available to recognize the larger form of the ORF3 protein are directed against synthetic peptides, and these sera are only capable of immunoprecipitating the smaller form of the ORF3 protein (9). We now report progress on the purification and characterization of the 35K ORF3 protein by use of the detergent CHAPS combined with preparative IEF and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry showed that both the 35K and the 23K forms were composed only of the ORF3 protein. Unfortunately, mass spectrometry analysis of tryptic peptides from the 35K form of ORF3 protein did not yield direct data on the phosphorylated amino acids within the domain of amino acids 180 to 212 associated with the formation of the larger form of ORF3 protein by mutant analysis.

However, the phosphorylated domain could be localized to amino acids 180 to 195 for several reasons. First, mass spectrometry did not detect any modifications to amino acids 196 to 212. Second, analysis of a mutant generated where the threonine at amino acid position 201 was changed to a valine (ORF3T201V) showed that this predicted site of phosphorylation was not important for the formation of the larger form, a result consistent with amino acid 201 being outside the phosphorylated domain based on the mass spectrometry data. Third, no change in protein migration of the 35K protein was detected following treatment with a protein tyrosine phosphatase (LAR; 2.5 U/20 μl; 0 to 24 h at 37°C; New England BioLabs) (data not shown). Inspection of amino acids 180 to 195 showed that there are five serines and three threonines in this region that could be phosphorylated, and sequence analysis of the ORF3 proteins of several noroviruses (Fig. 8) revealed that the five serines and two of the three threonines between amino acids 185 and 194 are conserved. These results suggest that some or all of Thr181/186/190 and Ser185/188/189/192/193 within this region could be phosphorylated. Because mass spectrometry is unable to identify peptides containing multiply phosphorylated amino acid residues, identification of the specific phosphorylation sites and types of phosphorylation in ORF3 will require further site-directed mutagenesis and analysis. It remains possible that this domain contains other posttranslational phosphorylation modifications, such as O-phosphate converted from O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (19). In addition, it remains of interest to identify the kinase responsible for this phosphorylation. In vitro kinase assays programmed with in vitro-translated ORF3 protein and protein kinase C or casein kinase II, two types of phosphorylation predicted within ORF3, did not result in the shift of the 23K to the 35K form, nor did it result in the autophosphorylation of this protein (unpublished data). Thus, additional studies are needed to identify the kinase.

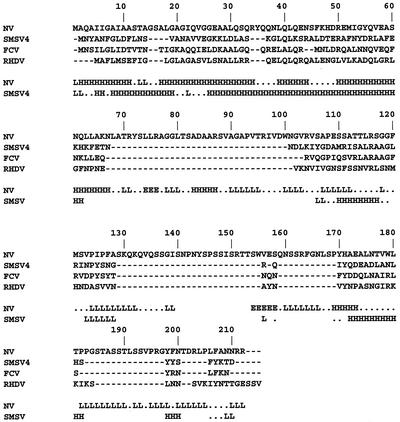

FIG. 8.

Sequence analysis of the ORF3 proteins of human and animal caliciviruses. Clustal W sequence alignment of the NV, SMSV-4, FCV, and RHDV ORF3 proteins. The PHD program was used to predict the secondary structures for the NV and SMSV ORF3 proteins which are displayed in the bottom two lines of each row. Amino acids are predicted to be part of a helical (H), loop (L), or beta sheet (E) structure.

Based on the results obtained to date, the 23K form of the ORF3 protein is unphosphorylated and the larger forms of the ORF3 protein are phosphorylated. The presence of a 35K form of the ORF3 protein in NV virions partially purified from NV-infected volunteers suggests that this larger form of ORF3 protein is made in mammalian cells (9), but further studies are needed to determine the role of phosphorylation in the NV replication cycle. Phosphorylation of proteins can play important regulatory roles in viral and cellular events. Mammalian transcription factors such as members of the STAT protein family have been described as phosphorylation-dependent homo- or heterodimers (5-7, 11, 12, 15, 23, 27, 28). These homo- or heterodimers enter the nucleus and bind DNA, resulting in the up-regulation of mRNA transcription (5). An RNA-binding protein of Escherichia coli is regulated by phosphorylation (1, 3), although in this system the monomeric form is phosphorylated and only the unphosphorylated dimer binds RNA (3). A nonstructural protein of rotavirus, NSP2, has been shown to bind RNA as a multimer, and this protein is phosphorylated. Multimers of rotavirus NSP2 have also been reported to interact with the RNA polymerase (20, 30). However, no link between phosphorylation and multimerization, polymerase binding, or RNA binding activities of NSP2 has been established. In our hands, we have found that both the nonphosphorylated form (23K) and phosphorylated larger 35K form of ORF3 protein can be detected in cells, although the appearance of the 35K form is delayed in insect cells (9). Influenza virus encodes several proteins that are posttranslationally phosphorylated, including the nucleoprotein, nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS2, the PA polymerase subunit, and M1 of the WSN strain. At least four of the different proteins involved in the formation of the ribonucleoprotein complexes (NS1, nucleoprotein, PA, and M1) are phosphoproteins. It has been speculated that the formation of the ribonucleoprotein complexes might be modulated by a phosphorylation-dephosphorylation mechanism (26). We hypothesize that the 23K and 35K forms of the calicivirus ORF3 protein play different roles during virus replication, and identifying these distinct functions is an ongoing endeavor.

Members of our laboratory previously showed that the NV ORF3 protein is a minor structural protein associated with both purified empty VLPs and partially purified NV virions (9). Similar findings have been reported for other caliciviruses. Studies of two animal caliciviruses, FCV and RHDV, have shown that the ORF3 or ORF3-equivalent protein is a minor structural protein of virions (29, 33). The 23K form of the NV ORF3 protein associates with the capsid protein in insect cells and is incorporated into VLPs that lack genomic RNA (9; this report). In a previous study, it was shown that expression of ORF2 and ORF3 from separate baculovirus recombinants results in the expression of both forms of the ORF3 protein; however, only the 23K form is associated with the empty rNV VLPs (9). To examine ORF3 protein-capsid protein interactions, the ORF3 mutants were coexpressed with ORF2 baculovirus recombinants and examined for interaction by coimmunoprecipitation and VLP incorporation analyses. Slightly different results were obtained depending on the analysis performed, which is likely due to differences in the sensitivity of the two assays. Coimmunoprecipitation analysis revealed that the ORF31-152 and ORF31-107 mutants were unable to interact with the ORF2 protein, while VLP incorporation analysis revealed that all of the ORF3 mutants, except the ORF31-107 mutant, interacted with the full-length ORF2 protein. Taken together, these data indicate that the region of the ORF3 protein between amino acids 108 and 152 contains the ORF2 interaction domain. While this is our preferred interpretation of our data, an alternative possibility is that additional amino acids 153 to 179 may confer increased binding of the ORF3 protein to the capsid protein, since neither ORF31-152 nor ORF31-107 interacted with the capsid protein in immunoprecipitation assays but ORF31-179 was detected in both immunoprecipitation assays and VLPs.

The domain on the ORF2 protein for interaction with the ORF3 protein remains unknown. The X-ray crystallographic structure of the NV capsid protein indicates that the first 49 amino acids of the capsid protein form the inner surface of VLPs (25). It has been hypothesized that the ORF3 protein interacts with this region for incorporation into VLPs. The results reported here with ORF2NT20 indicate that the ORF3 protein does not interact with the first 20 amino acids of the capsid protein. Future studies using additional ORF2 mutants should allow determination of the domain on the ORF2 protein that interacts with the ORF3 protein.

The ORF3 protein of human noroviruses is typically twice the size of the protein encoded by the vesiviruses and lagoviruses. While only a single ORF3 protein has been detected in infected cells and purified virions of FCV (14, 29), we have found two forms of the ORF3 protein in San Miguel sea lion virus serotype 4 (SMSV-4)-infected cells and partially purified virions that contain genomic RNA (P. J. Glass et al., unpublished data). Sequence alignments of ORF3 proteins indicate that there are regions of similarity between human and animal caliciviruses within the regions of the NV ORF3 protein we define in this paper as containing the domains responsible for the formation of the larger ORF3 protein and for ORF3 protein-capsid protein interactions (Fig. 8). Clustal W alignment analysis revealed a region of similarity among viruses between amino acids 108 and 128 of the NV ORF3 protein corresponding to the ORF2 interaction domain. Additionally, small regions of similarity are indicated between amino acids 180 and 212, corresponding to the domain involved in formation of the larger ORF3 protein. These findings lend support to the notion that these regions are important for all members of the Caliciviridae family. Within this region, no serine, threonine, or tyrosine residue is absolutely conserved among caliciviruses and can be used to base a prediction of a critical residue(s) for phosphorylation. Using the PHD program, both of the domains of NV identified in this paper are predicted to be loop structures, and for SMSV-4, the domains are predicted to be part helical and part looped in nature. Further analysis of these regions of the animal caliciviruses will be necessary to confirm the functional similarities suggested by the alignment analyses and the domains mapped in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the U.S. Public Health Service (grants AI38036 and AI46581), and P.J.G. was funded by a training fellowship (grant T32 AI07471) from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank B. V. V. Prasad, Andrea Bertolotti-Ciarlet, Tracy D. Parker, Sue Crawford, and Anne Hutson for critical comments and suggestions about this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amster-Choder, O., and A. Wright. 1992. Modulation of the dimerization of a transcriptional antiterminator protein by phosphorylation. Science 257:1395-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertolotti-Ciarlet, A., L. J. White, R. Chen, B. V. V. Prasad, and M. K. Estes. 2002. Structural requirements for the assembly of Norwalk virus-like particles. J. Virol. 76:4044-4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boss, A., A. Nussbaum-Shochat, and O. Amster-Choder. 1999. Characterization of the dimerization domain in BglG, an RNA-binding transcriptional antiterminator from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:1755-1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns, J. W., D. Chen, M. K. Estes, and R. F. Ramig. 1989. Biological and immunological characterization of a simian rotavirus SA11 variant with an altered genome segment 4. Virology 169:427-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee-Kishore, M., F. van den Akker, and G. R. Stark. 2000. Association of STATs with relatives and friends. Trends Cell Biol. 10:106-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decker, T., and P. Kovarik. 1999. Transcription factor activity of STAT proteins: structural requirements and regulation by phosphorylation and interacting proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 55:1535-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decker, T., and P. Kovarik. 2000. Serine phosphorylation of STATs. Oncogene 19:2628-2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fankhauser, R. L., J. S. Noel, S. S. Monroe, T. Ando, and R. I. Glass. 1998. Molecular epidemiology of “Norwalk-like viruses” in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1571-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glass, P. J., L. J. White, J. M. Ball, I. LeParc-Goffart, M. E. Hardy, and M. K. Estes. 2000. Norwalk virus open reading frame 3 encodes a minor structural protein. J. Virol. 74:6581-6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green, K. Y., A. Z. Kapikian, J. Valdesuso, S. Sosnovtsev, J. J. Treanor, and J. F. Lew. 1997. Expression and self-assembly of recombinant capsid protein from the antigenically distinct Hawaii human calicivirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1909-1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimley, P. M., F. Dong, and H. Rui. 1999. Stat5a and Stat5b: fraternal twins of signal transduction and transcriptional activation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 10:131-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gugneja, S., and R. C. Scarpulla. 1997. Serine phosphorylation within a concise amino-terminal domain in nuclear respiratory factor 1 enhances DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 272:18732-18739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hale, A. D., S. E. Crawford, M. Ciarlet, J. Green, C. Gallimore, D. W. Brown, X. Jiang, and M. K. Estes. 1999. Expression and self-assembly of Grimsby virus: antigenic distinction from Norwalk and Mexico viruses. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6:142-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbert, T. P., I. Brierley, and T. D. Brown. 1996. Detection of the ORF3 polypeptide of feline calicivirus in infected cells and evidence for its expression from a single functionally bicistronic, subgenomic mRNA. J. Gen. Virol. 77:123-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain, N., T. Zhang, S. L. Fong, C. P. Lim, and X. Cao. 1998. Repression of Stat3 activity by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Oncogene 17:3157-3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang, X., D. Y. Graham, K. N. Wang, and M. K. Estes. 1990. Norwalk virus genome cloning and characterization. Science 250:1580-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang, X., M. Wang, D. Y. Graham, and M. K. Estes. 1992. Expression, self-assembly, and antigenicity of the Norwalk virus capsid protein. J. Virol. 66:6527-6532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang, X., M. Wang, K. Wang, and M. K. Estes. 1993. Sequence and genomic organization of Norwalk virus. Virology 195:51-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamemura, K., B. K. Hayes, F. I. Comer, and G. W. Hart. 2002. Dynamic interplay between O-glycosylation and O-phosphorylation of nucleocytoplasmic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 277:19229-19235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kattoura, M. D., X. Chen, and J. T. Patton. 1994. The rotavirus RNA-binding protein NS35 (NSP2) forms 10S multimers and interacts with the viral RNA polymerase. Virology 202:803-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi, S., K. Sakae, Y. Suzuki, K. Shinozaki, M. Okada, H. Ishiko, K. Kamata, K. Suzuki, K. Natori, T. Miyamura, and N. Takeda. 2000. Molecular cloning, expression, and antigenicity of Seto virus belonging to genogroup I Norwalk-like viruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3492-3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.König, M., H.-J. Thiel, and G. Meyers. 1998. Detection of viral proteins after infection of cultured hepatocytes with rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus. J. Virol. 72:4492-4497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim, C. P., and X. Cao. 2001. Regulation of Stat3 activation by MEK kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 276:21004-21011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayo, M. A. 2002. A summary of taxonomic changes recently approved by the ICTV. Arch. Virol. 147:1655-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prasad, B. V. V., M. E. Hardy, T. Dokland, J. Bella, M. G. Rossman, and M. K. Estes. 1999. X-ray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus capsid. Science 286:287-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanz-Ezquerro, J. J., J. Fernandez Santaren, T. Sierra, T. Aragon, J. Ortega, J. Ortin, G. L. Smith, and A. Nieto. 1998. The PA influenza virus polymerase subunit is a phosphorylated protein. J. Gen. Virol. 79:471-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasse, J., U. Hemmann, C. Schwartz, U. Schniertshauer, B. Heesel, C. Landgraf, J. Schneider-Mergener, P. C. Heinrich, and F. Horn. 1997. Mutational analysis of acute-phase response factor/Stat3 activation and dimerization. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4677-4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shuai, K., C. M. Horvath, L. H. Huang, S. A. Qureshi, D. Cowburn, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1994. Interferon activation of the transcription factor Stat91 involves dimerization through SH2-phosphotyrosyl peptide interactions. Cell 76:821-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sosnovtsev, S. V., and K. Y. Green. 2000. Identification and genomic mapping of the ORF3 and VPg proteins in feline calicivirus virions. Virology 277:193-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taraporewala, Z. F., D. Chen, and J. T. Patton. 2001. Multimers of the bluetongue virus nonstructural protein, NS2, possess nucleotidyl phosphatase activity: similarities between NS2 and rotavirus NSP2. Virology 280:221-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vinje, J., S. A. Altena, and M. P. Koopmans. 1997. The incidence and genetic variability of small round-structured viruses in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in The Netherlands. J. Infect. Dis. 176:1374-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White, L. J., M. E. Hardy, and M. K. Estes. 1997. Biochemical characterization of a smaller form of recombinant Norwalk virus capsids assembled in insect cells. J. Virol. 71:8066-8072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wirblich, C., H.-J. Theil, and G. Meyers. 1996. Genetic map of the calicivirus hemorrhagic disease virus as deduced from in vitro translation studies. J. Virol. 70:7974-7983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]