Abstract

CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes infiltrate the parenchyma of mouse brains several weeks after intracerebral, intraperitoneal, or oral inoculation with the Chandler strain of mouse scrapie, a pattern not seen with inoculation of prion protein knockout (PrP−/−) mice. Associated with this cellular infiltration are expression of MHC class I and II molecules and elevation in levels of the T-cell chemokines, especially macrophage inflammatory protein 1β, IFN-γ-inducible protein 10, and RANTES. T cells were also found in the central nervous system (CNS) in five of six patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. T cells harvested from brains and spleens of scrapie-infected mice were analyzed using a newly identified mouse PrP (mPrP) peptide bearing the canonical binding motifs to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I H-2b or H-2d molecules, appropriate MHC class I tetramers made to include these peptides, and CD4 and CD8 T cells stimulated with 15-mer overlapping peptides covering the whole mPrP. Minimal to modest Kb tetramer binding of mPrP amino acids (aa) 2 to 9, aa 152 to 160, and aa 232 to 241 was observed, but such tetramer-binding lymphocytes as well as CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes incubated with the full repertoire of mPrP peptides failed to synthesize intracellular gamma interferon (IFN-γ) or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) cytokines and were unable to lyse PrP−/− embryo fibroblasts or macrophages coated with 51Cr-labeled mPrP peptide. These results suggest that the expression of PrPsc in the CNS is associated with release of chemokines and, as shown previously, cytokines that attract and retain PrP-activated T cells and, quite likely, bystander activated T cells that have migrated from the periphery into the CNS. However, these CD4 and CD8 T cells are defective in such an effector function(s) as IFN-γ and TNF-α expression or release or lytic activity.

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE) (e.g., prion disease and scrapie) are progressive, fatal neurodegenerative diseases of humans and other animals (10, 34). The hallmark of TSE diseases is the conversion of normal prion protein (PrPc) to an abnormal, protease-resistant form (PrPsc). Characteristic features are spongiosis, astrocytosis, and neuronal loss in the central nervous system (CNS). Of the many enigmas concerning this process, three stand out. First, how is TSE inheritable information encoded and transmitted in PrP in the absence of discernible nucleic acids; second, what are the pathophysiologic events by which PrPsc causes CNS disease; and third, why is there no detectable immune response accompanying scrapie infection (4, 5)? In this report, we use a model of scrapie in mice to focus on the pathophysiologic response in the CNS and on the immune response.

Within the brain, TSE disease generates an accumulation of protease-resistant proteins, PrPsc or PrPres, derived by a posttranslational event from a normal host-encoded protease-sensitive isoform, designated PrPc or PrPsen (10, 34). PrPc is attached by a glycolipid anchor to the cell surface. In the CNS, PrPc converts to PrPsc in both neurons and astrocytes (10, 13). In genetic experiments with PrP knockout (PrP−/−) mice, hamster PrPc was expressed only in neurons after using a neuron-specific enolase promoter (35) or in astrocytes upon using an astrocyte-specific glial fibrillary astrocyte protein (GFAP) promoter (37). In both instances, challenge with hamster scrapie resulted in TSE, thereby incriminating both neurons and astrocytes in the replication of PrPsc and in the disease process. Still unclear are how PrPc converts to PrPsc in these cells and how PrPsc accumulation gives rise to the profound neurodegeneration characteristic of scrapie.

Associated with ongoing TSE disease is the expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α), IL-1β, GFAP, and murine acute-phase response gene mRNA in the brain but not in peripheral tissues like spleen, kidneys, or liver (9). Absent or not altered in the TSE brains are IL-4, IL-5, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), IL-2, IL-6, and IL-3 mRNA (9). In addition to these cytokines, chemokines are present within and outside the CNS, where they function as soluble mediators possessing a spectrum of actions and chemotactic activities (3, 39, 46). Localized production of chemokines is possible from astrocytes and neurons, the two CNS cell types involved in conversion of PrPc to PrPsc. Yet expression of chemokines in the CNS during scrapie infection is unknown.

In this work, we evaluated the expression of chemokines as well as the presence of a cellular T-cell immune response in TSE. For that purpose, we studied scrapie-infected mice for the expression of multiple chemokine genes, infiltration of T lymphocytes, and presence of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules throughout the progression of TSE. We found that IFN-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10), macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), RANTES, and to a lesser extent MIP-1β mRNA were enhanced but not those of other chemokine molecules. We also noted T-cell infiltration into the parenchyma of the brains from scrapie-infected mice and in five of six patients with clinical, neuropathologic, and biochemically defined Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). Tetramer analysis of T cells from scrapie-infected mice suggests that such T cells may be specific to MHC-restricted prion peptides but incapable of lytic responses or PrP peptide-stimulated IFN-γ and TNF-α production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse strains, infectious agent, and infection protocol.

C57BL/6 (H-2b), BALB/WEHI or cdj (H-2d), FVB/N (H-2q), and SWR/J (H-2q) mice were bred under specific-pathogen-free conditions and obtained from the Rodent Breeding Colony of The Scripps Research Institute. As described previously (36, 37), the two sets of PrP−/− mice used included one group carrying a null mutation in PrP that abolished PrP mRNA production (such mice were crossed to H-2b mice) and another group with a truncation in PrP gene (crossed to H-2q mice). The former group was obtained from Jean Manson, Institute for Animal Health, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, and the latter group was developed by Charles Weissmann, Institute for Molecular Biology, Zurich, Switzerland, and obtained from Stanley Prusiner, University of California, San Francisco. Genetically deficient CD4 or CD8 mice came from The Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine. Mice genetically deficient in MHC class I and class II originated from Michael Grusby at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Mass. These mice were bred in The Scripps Research Institute vivarium core and genotyped and phenotyped as reported previously (26, 35, 37, 43). Mice were inoculated orally, intraperitoneally (i.p.), or intracerebrally (i.c.) with the specified doses of Chandler RML strain of mouse scrapie made as a 10% solution of brain homogenate in PBS and cleared of debris by low-speed centrifugation. The i.p. inoculation volume was 100 μl, and the i.c. inoculation volume was 30 μl. Oral infection was in a volume of 200 μl administered via a small-diameter flexible polypropylene catheter inserted over the base of the tongue about 1 to 2 cm into the esophagus as described previously (33). Infectious scrapie was quantitated after i.c. injection of serial 10-fold dilutions of a 10% brain homogenate into C57BL/6 mice (four mice/dilution).

The Armstrong (ARM) strain of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), clone 53b, was also used (33, 40). LCMV was plaque purified three times on Vero cells, and stocks were prepared by a single passage on BHK-21 cells. Eight- to twelve-week-old mice were infected with a single i.p. dose of 105 PFU. For secondary challenge, mice were inoculated with 106 PFU of LCMV i.p.

Brain material and clinical and neuropathologic synopsis of CJD patients and immunochemical studies.

The brains from six patients with sporadic CJD (sCJD) were examined and immunohistochemically stained for T- and B-cell markers (CD3 and CD20, respectively) in the Neuropathology Prion Disease Laboratory at the University of California in San Francisco. The patients' ages ranged from 55 to 73 years. All had the characteristic neurohistopathological feature of CJD, vacuolar (spongiform) degeneration of the gray matter. In addition, PrPsc was identified in each of the cases by the hydrolytic autoclaving method applied to formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded brain sections (30) and by the more sensitive and specific histoblot technique applied to unfixed, cryostat sections blotted to nitrocellulose paper (42).

Cell lines.

Mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEF) were made from both PrP−/− lines. Murine H-2b mutant RMA-S cells and human T2 cells transfected with H-2Db or transfected with H-2Ld molecules were grown as described previously (23). The murine H-2b cell line (MC57) and H-2d line (BALB Cl-7) were utilized as reported previously (40, 45). Cells were grown in either RPMI 1640 (RMA-S, MC-57, BALB Cl-7, and MEF) or Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (T2-Db and T2-Ld) containing 8% bovine serum, l-glutamine (2 mM), and antibodies (penicillin [10 U/ml] and streptomycin [10 μg/ml]). Geneticin (400 μg/ml) was added to Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium to maintain selection of T2-Db and T2-Ld cells.

Peptides.

Selected peptides representing motifs for H-2b or H-2d MHC alleles were synthesized on an automated peptide synthesizer (model 430A; Applied Biosystems) by the solid-phase method using 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl chemistry, purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography on an RP3000-C8 reverse-phase column, and identified by electrospray mass spectrometry (23). In addition, overlapping 15-mer peptides (see Table 3) that covered the mouse PrP (mPrP) sequence were purchased from Multiple Peptide Systems, San Diego, Calif.

TABLE 3.

Peptides of mPrP used in CD8 and CD4 T-cell assaysa

| mPrP or pool no. | aa sequence | mPrPs contained |

|---|---|---|

| mPrP no. | ||

| 1 | MANLGYWLLALFVTM | |

| 2 | YWLLALFVTMWTDVG | |

| 3 | LFVTMWTDVGLCKKR | |

| 4 | WTDVGLCKKRPKPGG | |

| 5 | LCKKRPKPGGWNTGG | |

| 6 | PKPGGWNTGGSRYPG | |

| 7 | WNTGGSRYPGQGSPG | |

| 8 | SRYPGQGSPGGNRYP | |

| 9 | QGSPGGNRYPPQGGT | |

| 10 | GNRYPPQGGTWGQPH | |

| 11 | PQGGTWGQPHGGGWG | |

| 12 | WGQPHGGGWGQPHGG | |

| 13 | GGGWGQPHGGSWGGP | |

| 14 | QPHGGSWGGPHGGSW | |

| 15 | SWGGPHGGSWGQPHG | |

| 16 | HGGSWGQPHGGGWGQ | |

| 17 | GQPHGGGWGQGGGTH | |

| 18 | GGWGQGGGTHNQWNK | |

| 19 | GGGTHNQWNKPSKPK | |

| 20 | NQWNKPSKPKTNLKH | |

| 21 | PSKPKTNLKHVAGAA | |

| 22 | TNLKHVAGAAAAGAV | |

| 23 | VAGAAAAGAVVGGLG | |

| 24 | AAGAVVGGLGGYMLG | |

| 25 | VGGLGGYMLGSAMSR | |

| 26 | GYMLGSAMSRPMIHF | |

| 27 | SAMSRPMIHFGNDWE | |

| 28 | PMIHFGNDWEDRYYR | |

| 29 | GNDWEDRYYRENMYR | |

| 30 | DRYYRENMYRYPNQV | |

| 31 | ENMYRYPNQVYYRPV | |

| 32 | YPNQVYYRPVDQYSN | |

| 33 | YYRPVDQYSNQNNFV | |

| 34 | DQYSNQNNFVHDCVN | |

| 35 | QNNFVHDCVNITIKQ | |

| 36 | HDCVNITIKQHTVTT | |

| 37 | ITIKQHTVTTTTKGE | |

| 38 | HTVTTTTKGENFTET | |

| 39 | TTKGENFTETDVKMM | |

| 40 | NFTETDVKMMERVVE | |

| 41 | DVKMMERVVEQMCVT | |

| 42 | ERVVEQMCVTQYGKE | |

| 43 | QMCVTQYGKESQAYY | |

| 44 | QYGKESQAYYDGRRS | |

| 45 | SQAYYDGRRSSSTVL | |

| 46 | DGRRSSSTVLFSSPP | |

| 47 | SSTVLFSSPPVILLI | |

| 48 | FSSPPVILLISFLIF | |

| 49 | VILLISFLIFLIVG | |

| Pool no. | ||

| 1 | 1, + 2, + 3, + 4, + 5, + 6, + 7 | |

| 2 | 8, + 9, + 10, + 11, + 12, + 13, + 14 | |

| 3 | 15, + 16, + 17, + 18, + 19, + 20, + 21 | |

| 4 | 22, + 23, + 24, + 25, + 26, + 27, + 28 | |

| 5 | 29, + 30, + 31, + 32, + 33, + 34, + 35 | |

| 6 | 36, + 37, + 38, + 39, + 40, + 41, + 42 | |

| 7 | 43, + 44, + 45, + 46, + 47, + 48, + 49 | |

| 8 | 1, + 8, + 15, + 22, + 29, + 36, + 43 | |

| 9 | 2, + 9, + 16, + 23, + 30, + 37, + 44 | |

| 10 | 3, + 10, + 17, + 24, + 31, + 38, + 45 | |

| 11 | 4, + 11, + 18, + 25, + 32, + 39, + 46 | |

| 12 | 5, + 12, + 19, + 26, + 33, + 40, + 47 | |

| 13 | 6, + 13, + 20, + 27, + 34, + 41, + 48 | |

| 14 | 7, + 14, + 21, + 28, + 35, + 42, + 49 |

Peptides comprising pools 1 through 14 were incubated at a concentration of 20 μg/ml for 5 h with a single-cell suspension of lymphocytes obtained from spleens of mice inoculated three times with murine scrapie (see Materials and Methods and reference 21) in the presence of recombinant IL-2 (10 to 50 U/ml) and brefeldin A (1 μg/ml) and stained with antibodies to either CD4 or CD8 and with antibody to IFN-γ conjugated to a difference fluorochrome. Cells were studied by fluorescence-activated cell sorting using two-color analysis (see Fig. 5).

Binding studies.

Peptide-MHC binding affinity was determined by measuring up-regulation of MHC molecule expression at the cell surface (MHC stabilization) induced by peptide added exogenously. The mutant cell line, in which transport of endogenous peptides to the endoplasmic reticulum is deficient, RMAS (Db, Kb), transfected with Kd molecules and the mastocytoma cell line P815 (H-2d) were used to measure Db, Kb, Kd, or Ld stabilization, as described previously (11, 23). Briefly, cells (5 × 105/well) were incubated at 37°C in microtiter plates in the presence of increasing peptide concentrations (10−10 to 10−5 M). The expression of peptide-stabilized MHC molecules was analyzed after a 4-h incubation period. Cells were incubated on ice for 1 h with 0.1 ml of hybridoma culture supernatant of mouse monoclonal antibody 28-14-8S (anti-Db, anti-Ld), Y3 (anti-Kb), or SF1-1.1.1 (anti-Kd). As negative controls, the cells were cultured in medium alone. After being washed once with ice-cold 1% bovine serum albumin-PBS and incubated for 1 h with the fluorescent secondary antibody (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G [IgG]), the cells were washed twice and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in 1% bovine serum albumin-PBS. Analysis followed in a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). The 50% stabilizing concentration (SC50) was an amount of peptide that produced half the maximal up-regulation. The peptides were considered to be MHC binders when displaying affinity values of 50 μM or lower. Positive control peptides for Db, Kb, Kd, and Ld binding were LCMV ARM NP amino acids FQPQNGQFI (21), Moloney murine leukemia virus peptide SSWDFITV (41), P198 tumor antigenic peptide KIQAVTTTL, and P29 peptide YPNVNIHNF (11), respectively.

Cytotoxic T-cell assay.

mPrP peptides at a concentration of 20 μg/ml were incubated with PrP−/− MEF labeled with 51chromium (15, 40, 45). Lymphocytes harvested from the brain (15) and spleen (40, 45) were added at effector-to-target cell ratios of 100:1, 50:1, and 25:1 for a 5-h assay as described elsewhere (15, 40, 45). As a positive control, PrP−/− MEF were infected with LCMV (multiplicity of infection, 1.0) for 48 h and added to lymphocytes harvested from scrapie-infected mice or from LCMV-infected mice as described elsewhere (15, 40, 45).

MHC class I tetramers.

Kb-restricted mPrP amino acids (aa) 2 to 9, aa 152 to 160, and aa 232 to 241; Db-restricted LCMV GP aa 33 to 41; Db-restricted LCMV NP aa 396 to 404; and Kb-restricted LCMV GP aa 34 to 43 were used as allophycocyanin or phycoerythrin conjugates. Either these were obtained from the Tetramer Core Facility, Emory University, Atlanta, Ga. (1), or in some instances, biotinylated MHC-peptide monomers were made as tetramers in our laboratory (21) immediately before use. Staining with MHC class I tetramers was performed at a 1:50 to 1:100 dilution in the presence of various surface antibodies for 30 min at 4°C, and propidium iodide was added at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml to allow analytical exclusion of dead cells (21).

Flow cytometry and cytokine ELISPOT.

Single-cell suspensions of lymphocytes were restimulated for 5 h with MHC class I- or class II-restricted peptides (1 or 2 μg/ml, respectively) in the presence of recombinant human IL-2 (10 to 50 U/ml; PharMingen, La Jolla, Calif.) and brefeldin A (1 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Staining for cell surface antigen and intracellular antigens was performed as described previously (21). Negative controls were peptide-stimulated cells obtained from uninfected mice, cells restimulated for 5 h in the absence of viral peptides, and cells stained with conjugated cytokine-specific antibodies preincubated for 30 min at 4°C with an excess of recombinant cytokine. Cells were acquired with FACSort or FACSCalibur flow cytometers (Becton Dickinson) using Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson). For five- and six-color analyses, a FACSVantage SE flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) was used. FITC-, phycoerythrin-, CyChrome-, peridinin chlorophyll-a protein-, or allophycocyanin-conjugated, biotinylated, and/or purified antibodies (PharMingen) were used to evaluate CD4 (RM4-5) and CD8a (53-6.7) cells and evaluated as described elsewhere (21, 40, 45).

Immunohistochemical staining of CNS tissues.

Brains removed from test mice were covered with Tissue-Tec OCT (Miles Diagnostics Division, Elkhart, Ind.), snap-frozen at −80°C in isopentane, and then stored at −20°C. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 6- to 10-μm-thick cryostat sections that were fixed in 100% ethanol for 15 min at 4°C and blocked with avidin and biotin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.). Staining was done with the following primary antibodies: anti-CD8 (anti-Ly-2 and Ly-3; PharMingen), anti-CD4 (anti-L3T4; PharMingen), anti-H-2 monotypic antigen (MHC class I), anti-Ia antigen (MHC class II), anti-B220 (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.), and anti-F4/80 (Serotec, Oxford, England). The second antibody was either a biotinylated anti-mouse IgG used in conjunction with the Vectastain Elite ABC (peroxidase) kit (Vector Laboratories) or anti-Ig-FITC. In the former case, staining was detected using diaminobenzidine as a chromogen. Sections were counterstained in Mayer's hematoxylin (Sigma) and mounted in Aqua-Mount (Lerner Laboratories, Pittsburgh, Pa.).

For light microscopy study, brain tissue was fixed in Bouin's fixative or 10% formaldehyde, prepared in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

RESULTS

Presence of CD8 and CD4 T cells in brains of scrapie-inoculated PrP+/+ but not PrP−/− mice.

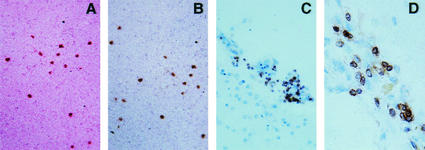

Twelve weeks after i.c. injection of 100,000 infectious doses of Chandler strain mouse scrapie into 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 and BALB mice, both CD8 and CD4 T cells infiltrated the brain parenchyma, including regions of the hippocampus, cortex, and cerebellum (Fig. 1A and B). These cells were easily discernible by immunochemical staining of brain sections with monoclonal antibodies to CD4 and CD8 T cells (15) (four to six mice per group; experiment repeated twice). Such infiltration rarely was perivascular, and it was not appreciated by light microscopy. No infiltration was seen at 6 or 10 weeks after inoculation of PrP+/+ mice or at any time in mice injected with PrP−/− (Table 1). Correspondingly, oral inoculation of 100,000 infectious doses of mouse scrapie into 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice led to classic clinical and histopathologic disease with conversion of PrPc to PrPsc in the CNS within 282 to 300 days. All six of these mice had CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell infiltrates as did all four murine recipients of 100,000 infectious doses at 185 days after i.p. inoculation. To the contrary, age-matched control mice not injected with scrapie had no CD8 or CD4 T cells in their brains (group of four mice), nor did brains from mice given scrapie orally contain either PrPsc or infiltrating CD8+ or CD4+ T cells 100 days after administration.

FIG. 1.

(A and B) CD8+ T-cell infiltration in the parenchyma of a C57BL/6 (A) and BALB/WEHI (B) mouse 18 weeks after i.c. inoculation with scrapie. (C and D) Micrographs of sections of autopsied CNS from two distinct patients with CJD stained with antibody to human T cells. In these human tissues, T cells most often lay near blood vessels but occasionally appeared in the brain parenchyma.

TABLE 1.

Immunohistologic study of the CNS during scrapie infection

| Mouse strain and cells | Expression in the CNS at wk postinoculationa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 10 | 12 | 18 | |

| C57BL/6 PrP+/+ | ||||

| CD8+ T | 0/4 | 0/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| CD4+ T | 0/4 | 0/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| MHC class I | 0/4 | 1/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| MHC class II | 0/4 | 0/4 | 2/4 | 3/4 |

| GFAP+ | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| F4/80+ | 0/4 | 0/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| Apoptosisb | 0/4 | 0/4 | 1/4 | 4/4 |

| MIP-1, IP-10 | 0/4 | ND | ND | 4/4 |

| RANTESc, C10c | 0/4 | ND | ND | 4/4 |

| MIP-2c | 1/4 | ND | ND | 4/4 |

| MCP-3, TCA-3c | 0/4 | ND | ND | 0/4 |

| BALB PrP+/+ | ||||

| CD8+ T | 0/4 | ND | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| CD4+ T | 0/4 | ND | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| MHC class I | 0/4 | ND | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| MHC class II | 0/4 | ND | 3/4 | 3/4 |

| GFAP+ | 4/4 | ND | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| F4/80+ | 0/4 | ND | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| Apoptosisb | 0/4 | ND | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| C57BL/6 PrP−/− | ||||

| CD8+ T | ND | ND | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| CD4+ T | ND | ND | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| MHC class I | ND | ND | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| Apoptosisb | ND | ND | 0/3 | 0/3 |

Expression of T cells in brains of mice and humans with TSE disease. Results are given as number of positive mice/total number of mice. ND, not determined

Apoptosis of neurons.

Chemokines in brains. Spleens were negative for chemokines at 6 and 18 weeks. Analysis by RPA.

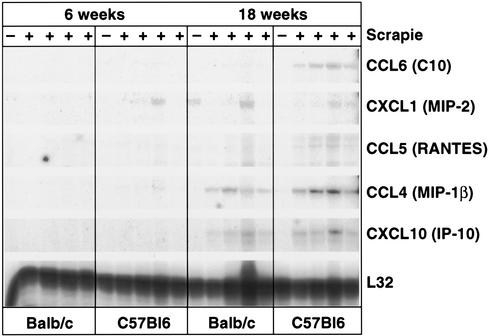

Other immunochemical analysis revealed a close temporal association of T-cell infiltration with the expression of MHC molecules, especially class I, and the presence of F4/80+ microglia or macrophages. Enhanced expression of MHC transcripts after scrapie infection was noted previously by Duguid and Trzepacz (14). Apoptosis of neurons lagged behind the detection of T cells. All these studies included stringent controls for antibody specificity and infection of CNS tissues (15, 22, 32). RNase protection assay (RPA) analysis (2, 9) displayed in Fig. 2 shows elevations of the T-cell chemokines—most prominently MIP-1β, IP-10, and RANTES—in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice with the macrophage chemokine C10 upregulated in brains of C57BL/6 but only minimally so in brains of BALB/c mice. MIP-2 was also enhanced in most mice during scrapie infection in the brain at 18 weeks and in a few infected mice at 6 weeks post-scrapie inoculation (Fig. 2). Other chemokines such as monocyte chemotactic protein 3 and TCA-3 were not elevated at any time point at either tissue site.

FIG. 2.

RPA analysis of brains harvested from scrapie-infected mice at 6 and 18 weeks post-i.c. inoculation. Individual mice were infected with scrapie (+) (pool of four). −, uninfected age- and sex-matched controls.

T-cell infiltration in humans with TSE disease.

Six brains from well-studied CJD patients were reevaluated for T-cell infiltration. As before, no T-cell infiltration was apparent by light microscopy. However, the application of antibody to human CD3 showed that T cells accumulated predominantly near or around blood vessels but also in the CNS parenchyma in five of the six brains studied. Shown in Fig. 1C and D are photomicrographs of brain tissues from two of the five patients with sCJD showing CD3 immunopositive lymphocytes. Tissues are from a cerebello-thalamo-striatal variant of sCJD with PrP-immunopositive kuru-type plaques in the cerebellum and the thalamus, and from a cortico-striato-olivo-cerebellar variant of sCJD, respectively.

Mapping mPrP peptide sequences that bound to H-2b (C57BL/6) or H-2d (BALB) MHC class I alleles.

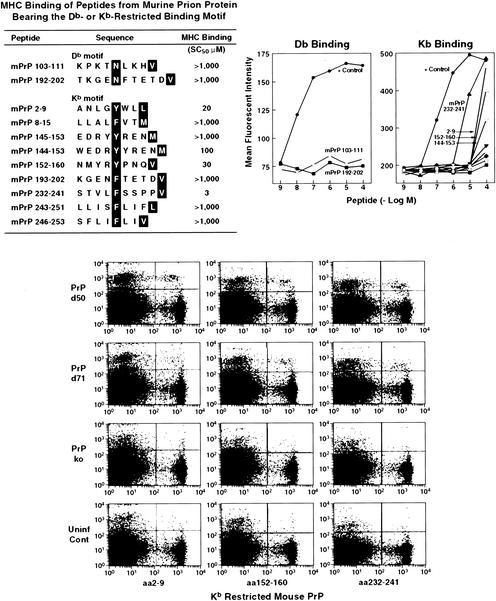

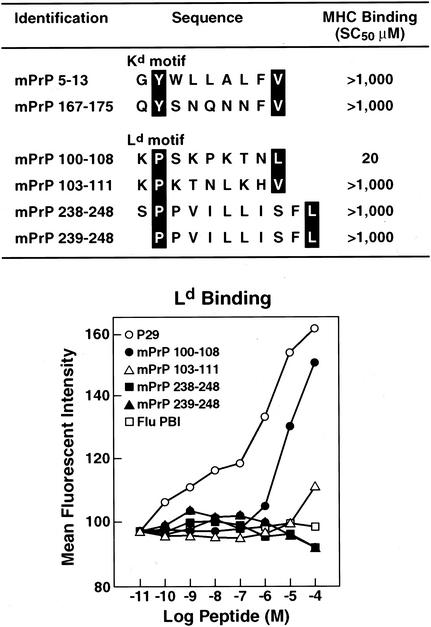

We then analyzed mPrP for peptide sequence motifs that were candidates for binding to Kb, Db, Kd, or Ld MHC class I alleles (23, 38, 41). Figures 3 and 4 display the prion sequences bearing murine MHC binding motifs: two for Db, nine for Kb, two for Kd, and four for Ld. These 17 peptides were then synthesized and tested for binding to their corresponding MHC class I alleles. For a MHC stabilization assay, RMAS cells (Db, Kb) transfected with Kd molecules and P815 (H-2d) were used to measure Db, Kb, Kd, or Ld stabilization in the presence of increasing peptide concentrations. Empty, unstable MHC molecules reaching the cell surface can be stabilized by peptides added exogenously. The affinity of a peptide for an MHC allele is tightly correlated to its ability to stabilize it. On this basis, MHC stabilization assays have been developed and are now commonly used to estimate the MHC binding properties of a given peptide. In our study, the positive control peptides exhibited affinity values (SC50) of 0.01 μM (Db binding [Fig. 3]), 0.1 μM (Kb binding [Fig. 3]), 1 μM (Ld binding [Fig. 3]), and 0.3 μM (Kd binding, not shown), respectively. The mPrP peptides were considered to be potent MHC binders when displaying affinity values (SC50) of 50 μM or less. In summary, we found that none of the peptides bearing the Db- or Kd-binding motif bound to their respective MHC alleles (SC50 > 1,000 μM), whereas one of the four Ld peptides (mPrP aa 100 to 108: KPSKPKTNL) bound to Ld (SC50 = 20 μM) and three of the nine Kb peptides (mPrP aa 2 to 9: ANLGYWLL; aa 152 to 160: NMYRYPNQV; and aa232 to 241: STVLFSSPPV) bound to Kb with SC50s of 20, 30, and 3 μM, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Motif of mPrP Db and Kb peptides that are appropriate for MHC class I binding (upper panels) and the data to show that only three of these mPrP peptides bind at heightened affinity to the corresponding MHC molecules. The lower panel displays data from three independent H-2b (C57BL/6) mice showing that their splenic lymphocytes bound to Kb tetramers containing mPrP aa 2 to 9, aa 152 to 160, and aa 232 to 241. Background binding for C57BL/6 control mice and C57BL/6 PrP−/− mice is shown. The positive control for Kb binding was Moloney murine leukemia virus peptide SSWDFITV (41), and that for Db binding was LCMV ARM NP peptide FQPQNGQFI (21). For binding, the horizontal axis of the graph shows the reciprocal log peptide dilution, while the vertical axis reflects the mean fluorescence intensity. Abbreviations: ko, knockout; Uninf Cont, uninfected control.

FIG. 4.

Motif of mPrP Kd and Ld peptides that are appropriate for MHC class I binding and data to show that only one of these peptides, mPrP 100 to 108, binds to Ld MHC molecules. The positive control for Ld binding is the P29 peptide YPNVNIHNF (11), and the negative control is the PB1 peptide VSDGGPNLY (12). For binding, the horizontal axis of the graph shows the reciprocal log peptide dilution, while the vertical axis reflects the mean fluorescence intensity.

Binding of Kb tetramers to lymphocytes harvested from scrapie-inoculated PrP+/+ mice.

Kb tetramers containing either mPrP aa 2 to 9, aa 152 to 160, or aa 232 to 241 were made (1) and showed low to modest but consistent binding to splenic lymphocytes at day 7 (data not shown) and days 50 and 71 (Fig. 3) after scrapie inoculation. Similar inoculation into PrP−/− mice gave lower levels (background) of lymphocyte binding to Kb tetramers at day 7 (data not shown) and days 50 and 71 post-scrapie infection (Fig. 3, data shown for three mice). On day 50, the mean lymphocyte-Kb tetramer binding values ±1 standard error were these: for aa 2 to 9, that for PrP+/+ mice was 2.1 ± 0.8, compared to 0.4 ± 0.3 for PrP−/− mice; for aa 152 to 160, that for PrP+/+ mice was 1.9 ± 0.8 and that for PrP−/− mice 0.2 ± 0.1; and for aa 232 to 241, that for PrP+/+ mice was 1.6 ± 0.8 and that for PrP−/− mice was 0.1 ± 0.4 (average of three to four mice per group). The results at day 71 were as follows: for aa 2 to 9, that for PrP+/+ mice was 1.2 ± 0.3 and that for PrP−/− mice was 0.5 ± 0.1; for aa 152 to 160, that for PrP+/+ mice was 1.4 ± 0.4 and that for PrP−/− mice was 0.2 ± 0.1; and for aa 232 to 241, that for PrP+/+ mice was 0.9 ± 0.5 and that for PrP−/− mice was 0.4 ± 0.4. Values of Kb tetramer binding to splenic lymphocytes harvested from PrP+/+ mice 7 days after scrapie inoculation were as follows: for aa 2 to 9, 2.6 ± 0.3; for aa152 to 160, 2.1 ± 0.3; and for aa 232 to 246, 1.2 ± 0.08 (three mice per group). Binding by Kb tetramers to lymphocytes from PrP−/− mice (three mice per group) 7 days after scrapie infection showed background values 30 to 50% lower than those to lymphocytes from PrP+/+ mice. Thus, binding values for each of these three Kb tetramers to splenic lymphocytes from scrapie-free C57BL/6 mice were 0.6 ± 0.8 or less at days 7, 50, or 71 of exposure. Because the Kb mPrP tetramers are relatively unstable, they were used within 2 to 3 weeks of labeling or made fresh preceding each experiment. Lymphocytes obtained from brains of mice 12 to 18 weeks after scrapie infection failed to bind to Kb tetramers, and other tetramers made to detect LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells (1, 21) failed to stain splenic lymphocytes from PrP+/+ mice (<0.4% of background values). Manufacture of Ld tetramers for mPrP was unsuccessful.

Effector function(s) of lymphocytes obtained from scrapie-inoculated PrP+/+ mice.

Next we examined whether CD4 or CD8 T cells infiltrating the CNS and the enhanced MHC expression contributed to the pathogenesis of scrapie. For these studies we employed several groups of mice made genetically deficient to CD4, CD8, MHC class I, or MHC class II molecules. However, deletion of CD4 or CD8 T cells did not significantly decrease the kinetics or incidence of developing scrapie, as shown in Table 2 and in agreement with a report by Klein et al. (24). Mice null for CD4 and CD8 T cells died or showed severe morbidity at 156 ± 8 or 154 ± 8 days (mean ± 1 standard error), respectively, compared to 148 ± 8 days for CD4 and CD8 T-cell-competent mice. Similarly, MHC class I and class II knockout mice developed severe disease at days 165 ± 5 or 158 ± 7, respectively, incubation periods similar to those of genetically normal mice. However, mice lacking both CD4 and CD8 T cells took 193 ± 5 days to show signs of clinical scrapie infection, a significantly longer period (P < 0.01) than that observed for wild-type mice or those lacking only one component, i.e., CD4−/−, CD8−/−, MHC class I−/−, or MHC class II−/− alone. These data were confirmed in a repeat experiment. In the limited number of MHC class I and MHC class II double-knockout mice available (total of four receiving i.c. and three receiving i.p. inoculations of scrapie) also showed prolonged incubation periods for developing clinical disease, taking longer than single-knockout MHC I or MHC II mice. All mice inoculated i.c. took at least 204 days to become moribund, and mice inoculated i.p. became clinically ill at or after 254 days. Within 8 days of becoming ill, all these MHC double-knockout mice died or were sacrificed because of severe morbidity, and neuropathologic and biochemical evidence of scrapie infection was found.

TABLE 2.

Enhanced survival of mice genetically deficient for both CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes to scrapie infection

| C57BL/6 mouse group | No. of mice | Survival time after inoculation with mouse scrapiea (mean no. of days ± SE)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| i.c. | i.p. | ||

| Wild type | 8 | 148 ± 8 | 189 ± 3 |

| CD4−/− | 8 | 156 ± 8 | NDb |

| CD8−/− | 8 | 154 ± 8 | ND |

| CD4−/− CD8−/− | 8 | 193 ± 5c | 242 ± 10c |

| MHC class I−/− | 6 | 165 ± 5 | ND |

| MHC class II−/− | 6 | 158 ± 7 | ND |

Mice were inoculated with 100,000 PFU of scrapie as described in Materials and Methods and sacrificed when moribund. The presence of scrapie was confirmed by pathogenomic findings on brain sections viewed by light microscopy (spondiosis, gliosis, and neuronal dropout) and by demonstration of conversion from PrPc to PrPsc by Western blotting (33, 35).

ND, not done.

P < 0.01.

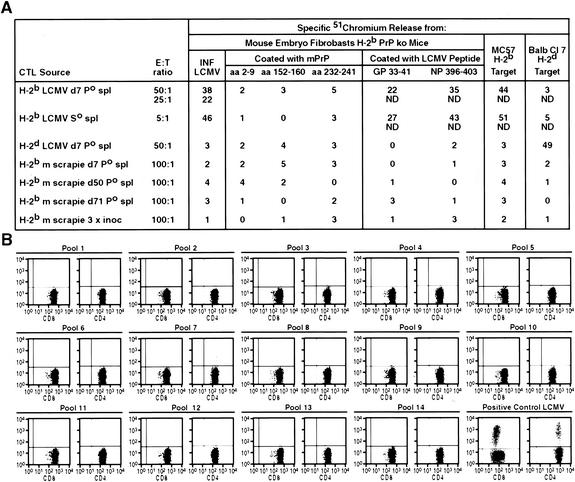

The final studies evaluated the effector functions of lymphocytes from scrapie-infected mice. Initially, lymphocytes were harvested from C57BL/6 or BALB/WEHI mice at 7, 14, 51, 70, or 150 days after primary inoculation of 100,000 PFU of scrapie or after two or three inoculations given i.p. 3 weeks apart. These splenic lymphocytes were then cultured with 51Cr-labeled PrP−/− MEF or, from PrP−/− mice, macrophages coated with the relevant Kb-restricted aa 2 to 9, aa 152 to 160, or aa 232 to 241 or Ld-restricted aa 100 to 108 prion peptide-peptide PrP−/− cells. No specific 51Cr release indicative of CTL activity was seen, although when lymphocytes originating from syngeneic mice infected 7 days earlier with LCMV were added to PrP−/− targets either infected with LCMV or coated with relevant LCMV peptide, significant lysis occurred (Fig. 5A). Similar negative results occurred with lymphocytes harvested from brains of scrapie-infected mice, whereas lymphocytes harvested from LCMV-infected mice (15) lysed syngeneic LCMV-infected targets. In subsequent experiments, lymphocytes were harvested on days 7, 50, or 71 after PrP+/+ mice were infected with scrapie, and mPrP aa 2 to 9, aa 152 to 160, and aa 232 to 241 failed to induce cytoplasmic expression of IFN-γ or TNF-α (data not shown) (8, 21, 29), although again expression of those cytokines was easily induced in mice at days 7, 50, or 120 after LCMV infection when their splenic lymphocytes were similarly incubated with relevant LCMV Kb, Db, or Ld peptides (21, 40). In addition, neither IL-2, IL-6, nor IL-10 expression was induced in lymphocytes harvested from PrP+/+ mice at similar times after scrapie infection and incubation with mPrP aa 2 to 9, aa 152 to 160, or aa 232 to 241, although IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10 were expressed in lymphocytes after LCMV infection (21, 40, 44).

FIG. 5.

(A) Lymphocytes obtained from the spleens of mice either primed once or three times with scrapie fail to lyse syngeneic PrP−/− target cells coated with 20 μg of those peptides which when separately placed in Kb tetramers bound such T cells (see Fig. 3). In contrast, T cells harvested from littermates primed seven days (Po) earlier with LCMV ARM 105 PFU i.p. or 60 days after initial priming receiving a second injection of LCMV ARM (So) lyse these PrP−/− target cells when they were infected with LCMV ARM 2 days earlier or coated with 20 μg of the LCMV GP peptide aa 33 to 41. See Materials and Methods and reference 21 for details of 51Cr-release assay and immunizations. Abbreviations: ko, knockout; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; E:T, effector-to-target cell; INF, infected; ND, not determined; spl, spleen; 3 × inoc, inoculated three times. (B) T cells obtained after multiple (three) inoculations with scrapie fail to generate intracytoplasmic IFN-γ when stimulated with the various pools of peptides that cover the mPrP sequence (see Table 3). Data are from a single mouse and representative of four additional mice. The positive control shows IFN-γ cytoplasmic staining for CD8 and CD4 T cells obtained 7 days after an inoculation with 105 PFU of LCMV ARM. Spleen lymphocytes were incubated with CD8 T-cell peptide LCMV GP aa 33 to 41 or CD4 T-cell peptide LCMV GP aa 61 to 80. See Materials and Methods and reference 21 for details.

Next, as shown in Table 3, we obtained 15-mer overlapping peptides of mPrP and arranged them in 14 groups for testing against splenic lymphocytes from scrapie-inoculated PrP+/+ mice. After one or three i.p. inoculations of 100,000 infectious doses of Chandler scrapie, each spaced 3 weeks apart, spleens were harvested, and single-cell suspensions of lymphocytes made and incubated with the various mPrP cocktails displayed in Table 3 and then stained and fixed to allow detection of intracellular cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α as well as molecules bound to CD4 or CD8 T cells. Although the accompanying control splenocytes from LCMV-immunized mice concurrently tested but with appropriate LCMV peptides gave positive results, we were unable to detect any convincing intracellular expression of IFN-γ (Fig. 5B) or TNF-γ (data not shown) in either CD8 or CD4 T cells from scrapie-inoculated mice. Notably, similar inoculation of murine scrapie into PrP−/− mice, due to a deletion of mPrP, also failed to reveal IFN-γ or TNF-α cytoplasmic expression in CD8 or CD4 T lymphocytes. Further, such lymphocytes from scrapie-infected PrP+/+ or PrP−/− mice failed to lyse syngeneic PrP−/− 51Cr-labeled MEF coated with the peptide cocktails (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

We found T cells in brains of mice and humans with TSE. Our kinetic studies, possible in the murine PrP+/+ model using the Chandler RML scrapie strain, located both CD4 and CD8 T cells within the brain by 12 weeks (84 days) and later after i.c. challenge, at 185 days after i.p. administration, and at 282 to 300 days after oral inoculation. No such infiltration of T lymphocytes followed similar inoculations of murine scrapie into PrP−/− mice or into uninoculated control mice. Nor did T cells appear in the brain or at 6 or 10 weeks after i.c. challenge or 100 days after oral inoculation of PrP+/+ mice. These results agree with those of Betmouni et al. (6, 7) who reported T-lymphocyte recruitment and microglia activation after i.c. inoculation of the ME7 strain of scrapie long before onset of clinical disease. In contrast to our studies, in which infiltrating T cells were not found in the brain 8 weeks after RML Chandler scrapie inoculation, these authors (6, 7) found T-cell infiltrates at that time but used a different strain of mouse scrapie.

Since only activated T cells are believed to cross the blood-brain barrier to enter the CNS, presumably scrapie infection was responsible for the initial T-cell activation. The cause could be generation of antigen-specific scrapie T cells or, alternatively or concomitantly, chemokine and cytokine chemoattractants induced during scrapie infection in the brain. We (20) and others (reviewed in references 3, 39, and 46) have incited cytokine and chemokine expression focally in selected tissues using transgenic approaches with cell-specific promoters and reported the resulting infiltration of lymphocytes into the target area. Our studies here are unable to discriminate between these two possibilities at present. The detection here of suspected PrP+/+ antigen-specific T cells by tetramers, but at low levels, was not associated with intracellular cytokine expression when such lymphocytes were incubated with the appropriate prion peptide(s). This finding is in accord with those of Zajac et al. (47), who reported an example of disassociation between tetramer-positive staining and intracellular cytokine staining in a viral model, while Field and Shenton (16) previously reported peripheral lymphocyte sensitization with TSE infection.

After entering the brain, activated T cells remain for approximately 10 to 14 days and then circulate out unless the recognition T-cell antigen appears expressed in the CNS milieu or appropriate chemokines are continuously present (15, 18). Although the presence of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and scrapie infection in the CNS bear a direct association, the lack of marked inflammatory cell recruitment to that site, coupled with the failure of T cells obtained from the periphery and the CNS to display detectable effector functions in vitro as cytotoxicity or expression or release of Th1 cytokines, suggests that these cells are minimally or not at all significant to the disease process. In agreement are earlier studies in which several immunosuppressive strategies or separate deletion of either CD4 or CD8 T cells did not alter the kinetics or outcome of scrapie infection (reviewed in references 4, 5, and 24). Further, the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ was not found in brains of mice succumbing to scrapie infection (9). However, as shown here, deletion of both CD4 and CD8 T cells significantly delayed the onset of disease, although once disease occurred, it was uniformly fatal. Hence, the delayed progression of disease and expression of TNF-α in brains of scrapie-infected mice (9) raise the possibility that the T-cell response may modestly influence the infection.

Why is it difficult to detect prion-specific T-cell response with scrapie infection? Arguments (reviewed in references 4 and 5) to explain such a phenomenon range from proposing a state of tolerance due to identical amino acid sequences between PrPc and PrPsc that is not broken either by scrapie infection or immunization with scrapie prions injected in adjuvant and the unusual protease resistance of PrPsc, which might prevent its degradation and processing in antigen-presenting cells. Yet, immune responses are reproducibly generated against other “self antigens” when the self protein or one of its peptide fragments is inoculated with adjuvants or during infections. For example, immune responses to CNS proteins like myelin basic protein, proteolipid protein of myelin, and myelin-associated oligodendrocyte basic protein, etc., are easily generated and often associated with corresponding autoimmune diseases (17, 19, 28, 48). Further, specific antiviral immune responses can be detected against endogenous murine retroviruses (31) that have existed in their hosts over thousands of years, most often infecting thymi and peripheral lymph nodes. Heterologous PrP in adjuvant can elicit immune (antibody) responses, suggesting that antigen processing of the PrP molecule can occur (25).

CD8 and CD4 T cells generated during scrapie infection, under the experimental conditions used here, were unable to mount effector functions. Of interest, this inability to act as lytic agents or cytokine producers also occurred when scrapie was inoculated into PrP−/− mice with a deletion of the PrP gene as well as PrP−/− mice that were unable to transcribe PrP because of an engineered mutation. However, it may be possible using other immunizing strategies or vehicles to express prions (i.e., DNA vaccination) that at least scrapie-specific CD4 T-cell responses can be generated, since antibodies to prions can be made. As for scrapie-specific CD8+ T cells, we mapped potential peptide motifs for MHC class I H-2b and H-2d molecules. Found were three CD8 T-cell motifs that bound well to Kb (SC50, 3, 20, and 30 μM) and one that bound to Ld (SC50, 20 μM) molecules. Kb tetramers made with these three mPrP peptides—aa 2 to 9, aa 152 to 160, and aa 232 to 241-bound, albeit to a modest extent, to splenic lymphocytes at days 7, 50, and 71 after scrapie inoculation. However, these lymphocytes from PrP+/+ mice were unable to synthesize the intracellular cytokines IFN-γ or TNF-α when stimulated with appropriate peptides and were unable to lyse 51chromium-labeled PrP−/− MEF coated with mPrP peptides. These findings are reminiscent of those from recent studies of CD4−/− mice infected with LCMV (47) and from a report characterizing circulating T cells for tumor-specific antigens (27). Lastly, the accumulation of T cells in the brains of scrapie-infected mice likely mirrors other models in which T cells accumulated and resided in the CNS following antigen-specific stimulation, when the recognized antigen was continuously expressed in the brain (15, 18) and/or when attracted by chemokines expressed in the CNS (3, 39, 46). Further analysis of these T cells and their induced genetic profiles should be of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants AG04342 (M.B.A.O., J.E.G., and D.H.), AG02132, AG10770 (S.D.), and MH50426 (I.L.C.); training grant AG00080 (D.H.); and postdoctoral fellowships from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (V.C.A.) and the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation (D.H.).

We thank Denis Hudrisier, INSERM, Toulouse University, France, for kind assistance in peptide prediction and MHC binding studies; John Altman, Vaccine Center Yerkes, Emory University Medical School, and the NIH Tetramer Core, for advice and assistance in making and providing prion tetramer reagents; Rick Race, NIH Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Laboratory of Persistent Viral Diseases, for assistance with the PrPsc analyses; and John Alcantara for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This is publication number 13546-NP from the Department of Neuropharmacology, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, Calif.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman, J. D., P. A. H. Moss, P. J. R. Goulder, D. H. Barouch, M. G. McHeyzer-Williams, J. I. Bell, A. J. McMichael, and M. M. Davis. 1996. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 274:94-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asensio, V. C., and I. L. Campbell. 1997. Chemokine gene expression in the brains of mice with lymphocytic choriomeningitis. J. Virol. 71:7832-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asensio, V. C., and I. L. Campbell. 1999. Chemokines in the CNS: plurifunctional mediators in diverse states. Trends Neurosci. 22:504-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aucouturier, P., R. I. Carp, C. Carnaud, and T. Wisniewski. 2000. Prion diseases and the immune system. Clin. Immunol. 96:79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg, L. J. 1994. Insights into the role of the immune system in prion diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:429-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betmouni, S., and V. H. Perry. 1999. The acute inflammatory response in CNS following injection of prion brain homogenate or normal brain homogenate. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 25:20-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betmouni, S., V. H. Perry, and J. L. Gordon. 1996. Evidence for an early inflammatory response in the central nervous system of mice with scrapie. Neuroscience 74:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butz, E. A., and M. J. Bevan. 1998. Massive expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during an acute virus infection. Immunity 8:167-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell, I. L., M. Eddleston, P. Kemper, M. B. A. Oldstone, and M. V. Hobbs. 1994. Activation of cerebral cytokine gene expression and its correlation with onset of molecular pathology in scrapie. J. Virol. 68:2383-2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesebro, B. 1999. Prion protein and the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy diseases. Neuron 24:503-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corr, M., L. F. Boyd, S. R. Frankel, S. Kozlowski, E. A. Padlan, and D. H. Margulies. 1992. Endogenous peptides of a soluble major histocompatibility complex class I molecule, H-2Lds: sequence motif, quantitative binding, and molecular modeling of the complex. J. Exp. Med. 176:1681-1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiBrino, M., T. Tsuchida, R. V. Turner, K. C. Parker, J. E. Coligan, and W. E. Biddison. 1993. HLA-A1 and HLA-A3 T cell epitopes derived from influenza virus proteins predicted from peptide binding motifs. J. Immunol. 151:5930-5935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diedrich, J. F., P. E. Bendheim, Y. S. Kim, R. I. Carp, and A. T. Haase. 1991. Scrapie-associated prion protein accumulates in astrocytes during scrapie infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:375-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duguid, J., and C. Trzepacz. 1993. Major histocompatibility complex genes have an increased brain expression after scrapie infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:114-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans, C. F., M. S. Horwitz, M. V. Hobbs, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1996. Viral infection of transgenic mice expressing a viral protein in oligodendrocytes leads to chronic central nervous system autoimmune disease. J. Exp. Med. 184:2371-2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field, E. J., and B. K. Shenton. 1975. Cellular sensitization in kuru, Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease and multiple sclerosis: with a note on the biohazards of slow infection work. Acta Neurol. Scand. 51:299-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammerling, G. J., G. Schonrich, F. Momburg, N. Auphan, M. Malissen, B. Malissen, A.-M. Schmitt-Verhulst, and B. Arnold. 1991. Non-deletional mechanisms of peripheral and central tolerance: studies with transgenic mice with tissue-specific expression of a foreign MHC class I antigen. Immunol. Rev. 122:47-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawke, S., P. G. Stevenson, S. Freeman, and C. R. M. Bangham. 1998. Long-term persistence of activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes after viral infection of the central nervous system. J. Exp. Med. 187:1575-1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holz, A., B. Bielekova, R. Martin, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 2000. Myelin-associated oligodendrocytic basic protein: identification of an encephalitogenic epitope and association with multiple sclerosis. J. Immunol. 164:1103-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holz, A., K. Brett, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 2001. Constitutive beta cell expression of IL-12 does not perturb self-tolerance but intensifies established autoimmune diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 108:1749-1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Homann, D., L. Teyton, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 2001. Differential regulation of antiviral T cell immunity results in stable CD8+ but declining CD4+ T cell memory. Nat. Med. 7:913-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horwitz, M. S., C. F. Evans, F. G. Klier, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1999. Detailed in vivo analysis of interferon-gamma induced major histocompatibility complex expression in the central nervous system: astrocytes fail to express major histocompatibility class I and II molecules. Lab. Investig. 79:235-242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudrisier, D., H. Mazarguil, F. Laval, M. B. A. Oldstone, and J. E. Gairin. 1996. Binding of viral antigens to major histocompatibility complex class I H-2Db molecules is controlled by dominant negative elements at peptide non-anchor residues: implications for peptide selection and presentation. J. Biol. Chem. 271:17829-17836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein, M. A., R. Frigg, E. Flechsig, A. J. Raeber, U. Kalinke, H. Bluethmann, F. Bootz, M. Suter, R. M. Zinkernagel, and A. Aguzzi. 1997. A crucial role for B cells in neuroinvasive scrapie. Nature 390:687-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krasemann, S., M. H. Groschup, S. Harmeyer, G. Hunsmann, and W. Bodemer. 1996. Generation of monoclonal antibodies against human prion proteins in PrP0/0 mice. Mol. Med. 2:725-734. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laufer, T. M., M. G. von Herrath, M. J. Grusby, M. B. A. Oldstone, and L. H. Glimcher. 1993. Autoimmune diabetes can be induced in transgenic major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 178:589-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, P. P., C. Yee, P. A. Savage, L. Fong, D. Brockstedt, J. S. Weber, D. Johnson, S. Swetter, J. Thompson, P. D. Greenberg, M. Roederer, and M. M. Davis. 1999. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nat. Med. 5:677-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller, A., D. A. Hafler, and H. L. Weiner. 1991. Tolerance and suppressor mechanisms in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: implications for immunotherapy of human autoimmune diseases. FASEB J. 5:2560-2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murali-Krishna, K., J. D. Altman, M. Suresh, D. J. Sourdive, A. J. Zajac, J. D. Miller, J. Slansky, and R. Ahmed. 1998. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 8:177-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muramoto, T., T. Kitamoto, J. Tateishi, and I. Goto. 1992. The sequential development of abnormal prion protein accumulation in mice with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Am. J. Pathol. 140:1411-1420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oldstone, M. B. A., T. Aoki, and F. J. Dixon. 1972. The antibody response of mice to murine leukemia virus in spontaneous infection. Absence of classical immunologic tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 69:134-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oldstone, M. B. A., H. Lewicki, D. Thomas, A. Tishon, S. Dales, J. Patterson, M. Manchester, D. Homann, and A. Holz. 1999. Measles virus infection in a transgenic model: virus-induced central nervous system disease and immunosuppression. Cell 98:629-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oldstone, M. B. A., R. Race, D. Thomas, H. Lewicki, D. Homann, S. C. Smelt, A. Holz, P. A. Koni, D. Lo, B. Chesebro, and R. A. Flavell. 2002. Lymphotoxin-alpha- and lymphotoxin-beta-deficient mice differ in susceptibility to scrapie: evidence against dendritic cell involvement in neuroinvasion. J. Virol. 76:4357-4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prusiner, S. B. 2001. Prions, p. 3063-3087. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 35.Race, R. E., S. A. Priola, R. A. Bessen, D. Ernst, J. Dockter, G. F. Rall, L. Mucke, B. Chesebro, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1995. Neuron-specific expression of a hamster prion protein minigene in transgenic mice induces susceptibility to hamster scrapie agent. Neuron 15:1183-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raeber, A. J., S. Brandner, M. A. Klein, Y. Benninger, C. Musahl, R. Frigg, C. Roeckl, M. B. Fischer, C. Weissmann, and A. Aguzzi. 1998. Transgenic and knockout mice in research on prion diseases. Brain Pathol. 8:715-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raeber, A. J., R. Race, S. Brandner, S. A. Priola, A. Sailer, R. A. Bessen, L. Mucke, J. Manson, A. Aguzzi, M. B. A. Oldstone, C. Weissmann, and B. Chesebro. 1997. Astrocyte-specific expression of hamster prion protein (PrP) renders PrP knockout mice susceptible to hamster scrapie. EMBO J. 16:6057-6065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rammensee, H. G., T. Friede, and S. Stevanoviic. 1995. MHC ligands and peptide motifs: first listing. Immunogenetics 41:178-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ransohoff, R. M., A. Glabinski, and M. Tani. 1996. Chemokines in immune-mediated inflammation of the central nervous system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 7:35-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sevilla, N., D. Homann, M. von Herrath, F. Rodriguez, S. Harkins, J. L. Whitton, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 2000. Virus-induced diabetes in a transgenic model: role of cross-reacting viruses and quantitation of effector T cells needed to cause disease J. Virol. 74:3284-3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sijts, A. J. A. M., M. L. H. DeBruijn, M. E. Ressing, J. D. Nieland, E. A. M. Mengede, C. J. P. Boog, F. Ossendorp, W. M. Kast, and C. J. M. Melief. 1994. Identification of an H-2 Kb-presented Moloney murine leukemia virus cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope that displays enhanced recognition in H-2 Db mutant bm13 mice. J. Virol. 68:6038-6046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taraboulos, A., K. Jendroska, D. Serban, S.-L. Yang, S. J. DeArmond, and S. B. Prusiner. 1992. Regional mapping of prion proteins in brains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:7620-7624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tishon, A., H. Lewicki, G. Rall, M. G. von Herrath, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1995. An essential role for type 1 interferon gamma in terminating persistent viral infection. Virology 212:244-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Herrath, M., J. Dockter, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1994. How virus induces a rapid or slow onset insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in a transgenic model. Immunity 1:231-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Herrath, M. G., D. P. Berger, D. Homann, T. Tishon, A. Sette, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 2000. Vaccination to treat persistent viral infection. Virology 268:411-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, J., V. C. Asensio, and I. L. Campbell. 2002. Cytokines and chemokines as mediators of protection and injury in the central nervous system assessed in transgenic mice. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 265:23-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zajac, A. J., J. N. Blattman, K. Murali-Krishna, D. J. Sourdive, M. Suresh, J. D. Altman, and R. Ahmed. 1998. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J. Exp. Med. 188:2205-2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zaller, D. M., and V. S. Sloan. 1996. Transgenic mouse models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 206:15-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]