Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether managed care is associated with reduced access to mental health specialists and worse outcomes among primary care patients with depressive symptoms.

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study.

SETTING

Offices of 261 primary physicians in private practice in Seattle.

PATIENTS

Patients (N = 17,187) were screened in waiting rooms, enrolling 1,336 adults with depressive symptoms. Patients (n = 942) completed follow-up surveys at 1, 3, and 6 months.

MEASUREMENTS AND RESULTS

For each patient, the intensity of managed care was measured by the managedness of the patient's health plan, plan benefit indexes, presence or absence of a mental health carve-out, intensity of managed care in the patient's primary care office, physician financial incentives, and whether the physician read or used depression guidelines. Access measures were referral and actually seeing a mental health specialist. Outcomes were the Symptom Checklist for Depression, restricted activity days, and patient rating of care from primary physician. Approximately 23% of patients were referred to mental health specialists, and 38% saw a mental health specialist with or without referral. Managed care generally was not associated with a reduced likelihood of referral or seeing a mental health specialist. Patients in more-managed plans were less likely to be referred to a psychiatrist. Among low-income patients, a physician financial withhold for referral was associated with fewer mental health referrals. A physician productivity bonus was associated with greater access to mental health specialists. Depressive symptom and restricted activity day outcomes in more-managed health plans and offices were similar to or better than less-managed settings. Patients in more-managed offices had lower ratings of care from their primary physicians.

CONCLUSIONS

The intensity of managed care was generally not associated with access to mental health specialists. The small number of managed care strategies associated with reduced access were offset by other strategies associated with increased access. Consequently, no adverse health outcomes were detected, but lower patient ratings of care provided by their primary physicians were found.

Keywords: managed care programs, access, insurance, behavioral medicine, depression, primary care, mental health services, physician referral, outcome assessment, quality of care, internal medicine, family medicine, psychiatry, psychology

Depression is a common, serious illness in primary care, and depressed patients are high consumers of health care. In 1990, the direct U.S. treatment costs for depression were $12 billion, with $1–2.9 billion for mental health specialists.1 General medical expenditures for depressed patients are often double the expenditures of nondepressed patients.2 One way in which managed care organizations (MCOs) control these costs is by restricting access to specialists.3 Highly managed MCOs typically impose controls that encourage primary physicians to treat most forms of depression and to limit referrals to higher-cost psychiatrists.4–6 Few studies have examined whether managed care controls are associated with reduced access to mental health specialists or worse outcomes for primary care patients with depressive symptoms.4,7–9

Most studies in this field have compared fee-for-service patients with patients having some type of managed care. Today, this approach is problematic because MCOs are managing both the cost and quality of care in different ways, and there is a continuum of “managedness,” rather than a sharp dichotomy with fee-for-service care.10 One way to overcome this problem is to define the strategies used by health plans, medical offices, and physicians to manage costs and improve quality of care.10 As the number and strength of these strategies increase, so does the intensity, or ‘managedness,’ of the MCO.

We sought to determine whether greater intensity of managed care is associated with reduced access to mental health specialists and worse outcomes for primary care patients with depressive symptoms.

METHODS

Design and Populations

In our Physician Referral Study, the physician population consisted of 832 primary care physicians (family practitioners, general internists, and general practitioners) in private practice at least 50% time in the Seattle metropolitan area. Of these, 261 physicians (31%) in 72 offices consented to participate in the study. Participating physicians and their office managers, as well as a random sample of 300 nonparticipating physicians, were asked to complete self-administered questionnaires at baseline.

Using a prospective cohort design, 17,187 English-speaking patients aged 18 and over were screened in waiting rooms to identify 1,336 consenting patients with depressive symptoms. Symptoms were measured using 6 items from the 20-item Symptom Checklist for Depression (SCL-20)11 with known sensitivity and specificity for detecting depression in primary care.12 Patients received 1-month, 3-month and 6-month follow-ups to collect personal characteristics, measures of referral, specialist utilization, health status, and rating of care from primary physician. The 3-month follow-up was performed because a majority of depression patients improve by 4 months, and managed care associations may be different at 3 month follow-up than at 6-month.13 Primary care record reviews were performed for a 12-month pre-study interval and a 6-month, post-baseline interval to collect data on primary care visits and physician referrals.

This analysis is based on 942 patients with complete data. Compared to those who were lost to follow-up, these were older, had fewer depressive symptoms, and were less likely to have seen a psychiatrist in the past 6 months.

Physician Referral and Specialist Utilization Measures

Referral by the primary physician to a mental health specialist was measured using patient report or chart evidence of referral within 6 months after the waiting room screen, or baseline. There were 2 measures of whether a referral was made: 1) referral to any mental health specialist, including a psychiatrist, psychologist, master-level or other mental health specialist; and 2) referral specifically to a psychiatrist.

Specialist utilization, with or without a referral, was measured by patient report of visiting a mental health specialist within 6 months after enrollment. Two measures, analogous to those used for referral, were constructed. We also measured whether a patient saw any mental health specialist with a referral.

Outcome Measures

Health status was assessed at baseline and each follow-up. Depressive symptoms were measured by the SCL-20,11 where a score of 1.75 or higher indicates severe depressive symptoms.14 Restricted activity was measured by the number of days the patient was limited in usual activities due to emotional health problems in the past 4 weeks.15 We computed change scores (baseline score minus follow-up score) for each outcome so that bigger, positive scores indicated more improvement.

Patients rated the health care provided by their primary physicians at the 6-month follow-up on a 6-point scale of poor (1), fair, good, very good, excellent, and outstanding (6).16

Managed Care Measures

On the basis of our conceptual model of managed care,8 we identified managed care controls in 3 settings or “levels”: health plans, primary care offices, and primary physician practices.

For managed care by health plans, we collected information from medical offices and patient screening to identify each patient's source of health insurance (e.g., a health insurance firm, Medicare, Medicaid), and we collected information for all health plans offered by each source. Four health plan indexes, each ranging from 0 to 100, were constructed using principal component analysis from the plan measures in cells A–D in Table 1.10 A plan managed care index (where 100 was a highly managed health plan) measured the intensity of provider-oriented controls in a health plan based on the gatekeeping and lock-in provisions of the plan's network (cell B), the plan's referral preauthorization requirements (cell C), and whether the plan versus the provider was at financial risk (cell D). An in-network benefits index measured the benefits (services covered) and cost sharing (copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles) in a plan's network, where 100 indicates the least out-of-pocket cost for standard benefits when services are delivered by providers in the network (cell A). An out-of-network benefits index measured the benefits and cost sharing outside a plan's network, where 100 indicates the least out-of-pocket cost for standard benefits when services are delivered by providers outside the plan's network (cell A). A mental health benefits index measured the inpatient and outpatient mental health benefits inside and outside the plan's network, where 100 indicates the least out-of-pocket costs. The construction and validity of the indexes were reported elsewhere.10 Another variable indicated whether the plan had a mental health carve-out.17 The benefit indexes were included because some managed plans, such as preferred provider organizations, control costs partly through greater patient cost sharing.

Table 1.

Strategies for Managing Health Care by Setting

| Setting | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Care | |||

| Managed Care Strategies | Health Plan | Office | Physician |

| Benefits and cost sharing | A | ||

| In-network and out-of-network benefit (+) and cost-sharing (−) arrangements | |||

| Network characteristics | B | ||

| Patient must see PCP before seeing specialist with coverage (−) | |||

| Patients can only see network specialists with coverage (−) | |||

| Utilization management | C | E | |

| Whether plan preauthorization is required before seeing specialist (−) | Office prior approval required before referring patient to specialist inside office (−) | ||

| Whether PCP preauthorization is required before seeing specialist (−) | Office prior approval required before referring patient to specialist outside office (−) | ||

| Financial incentives | D | F | H |

| Whether the plan pays the clinic or providers by fee-for-service or capitation (financial risk; [−] if fee-for-service) | Percentage of office revenue from capitation (−) | Whether PCP has a financial withhold for referrals (−) | |

| Whether PCP is paid by salary vs some form of fee-for-service (+) | |||

| Whether the PCP receives a productivity bonus (+) | |||

| Clinical guidelines and critical pathways | G | I | |

| Office follows written referral guidelines for specific conditions (0) | PCP has read or used the AHCPR clinical guideline for depression (0)* | ||

| Office follows written clinical guidelines for treating specific conditions (0) | |||

See Rush et al.18

PCP denotes primary care physician; (+), the managed care feature may be associated with greater access to mental health specialists; (−), lower access; (0), either greater or lower access; AHCPR, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research.

Office managed care was measured using the following controls: utilization management (the office's referral preauthorization requirements, cell E); financial incentives (percentage of office revenue from capitation, cell F); and clinical guideline measures (cell G). Because the office variables were correlated strongly, we created an office managed care index using principle component analysis. A single factor explained 60% of the total variation of the 5 variables; factor loadings were positive and ranged between 0.62 and 0.87. Factor scores were transformed to create a 0–100 office managed care index, where higher scores indicated more-managed offices.

Physician managed care was measured by financial incentives (how the primary physician was paid, whether the physician received a bonus or had a financial withhold for referrals, cell H) and whether the physician read or used the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) clinical guideline for depression (cell I).

On the basis of theory and empirical evidence,8 the managed care measures may be associated with either greater or less access to specialists, as indicated in Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

Patient measures included age, gender, race, living alone, employment status, education, annual household income. The number of comorbidities at baseline was assessed using a checklist of 21 comorbid conditions based on the Medical Outcomes Study.19 We also measured the context of care, whether the primary physician at baseline was the patient's usual source of care, and whether the patient had visits to a mental health specialist in the 6 months before the baseline visit.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to understand patterns of referral, utilization of mental health specialists, and outcomes. Bivariate analyses examined whether referrals and utilization of mental health specialists were associated with prior visits to mental health specialists in the 6 months before baseline.

Associations between the 8 managed care variables and the 8 referral and specialist utilization variables were identified using logistic regression models, which had 2 forms. In the patient form, we entered a single managed care variable and the following patient covariates: sociodemographic characteristics, baseline health status, whether the primary care physician was the patient's usual source of care, and whether the patient reported seeing a mental health specialist within 6 months before baseline. In total, 60 models were estimated (6 referral and specialist utilization variables × 10 managed care variables). Models were estimated for all patients, the subgroup of patients with referrals, and the subgroup of patients who saw mental health specialists.

Second, because managed care controls do not operate in isolation, we also estimated a full model for each referral and specialist utilization variable containing patient covariates and all managed care variables.20,21 Because of high correlation between the managed care index and out-of-network benefits index (r = −.76; P = .0001), we estimated the models without the out-of-network benefits index, and then re-estimated the models with the out-of-network benefits index but without the plan index.

The 0–100 health plan and office indexes were coded in 10-unit increments (0–9, 10–19, and so forth) to ease interpretation of odds ratios (ORs). We added index-squared terms to examine nonlinear associations between the index variables and the dependent variables.

Associations between the managed care variables and change in health status between baseline and the 6-month follow-up were identified using the same 2 forms (patient and full) of ordinary least squares regression models. Covariates included the baseline score of the dependent variable, patient sociodemographic characteristics, number of medical comorbidities, whether the patient had concurrent depression and pain, whether the primary care physician was the patient's usual source of medical care, and whether the patient reported seeing a mental health specialist in the 6 months before baseline. This analysis was repeated for health outcomes at the 3-month follow-up. This model also was used to determine the associations between the managed care variables and patient rating of health care from their primary physicians.

Associations between the managed care variables and health outcomes may be influenced by primary care visits and specialist utilization in the 6-month follow-up period. We repeated the outcome regressions, adding the following measures as endogenous control variables: 1) number of primary physician visits for depression in the follow-up period based on chart evidence, and 2) whether the patient saw a mental health specialist.

Because restricting access to specialists may be most detrimental for patients with more severe depressive symptoms,22 interaction tests were performed to determine whether associations between managed care and health outcomes differed for patients with baseline SCL scores greater or less than 1.75. We also tested whether the associations between managed care and health outcomes differed for patients with and without prior visits to mental health specialists, and those with household incomes greater or less than $20,000.15,23 Because the prevalence of depression was lower in older adults, and because Medicare enrollees were, on average, in less-managed health plans, we also tested whether the managed care associations differed for patients over and under age 65.

If persons with poor health selected health plans with greater benefits, or less managedness, this selection bias could be confused with an effect of the health plan. We used 3 methods of accounting for selection bias, all methods adjusting for the covariates mentioned above. First, we estimated propensity scores predicting, for example, the managed care index of the person's health plan from the patient covariates, then separated the patients into low versus high predicted groups at the median, and repeated the regressions in each stratum.24 Given reduced sample sizes and power for each group, in each new regression we checked only whether the sign and size of the regression coefficient for the health plan and benefit index of interest were consistent with the original regression coefficient.

Second, using information about all the plans offered by the employer or source of health insurance, we calculated the minimum, maximum, and mean managedness score of all plans offered by the source, and used these to predict the managed care index of the person's actual insurance plan. Then, we re-estimated the basic regressions described above, adjusting also for the expected managedness of the patient's health plan, based on the source. Third, in another regression, we adjusted for the difference between the managed care index of the person's plan and the average index of the plans offered by the employer. In each new regression equation, we checked whether the statistical significance and sign of the regression coefficient for the index of interest was consistent with the original regression coefficient.

Patients were excluded from regression models when data were missing because the patient did not complete the follow-up, information about the patient's health plan was missing, or the patient's physician or office manager did not complete questionnaires. To account for patients with missing data, we estimated propensity scores predicting whether a patient was included versus excluded because of missing data, separated the patients into low versus high predicted groups at the median, and repeated regressions for each group.

Models were estimated with STATA statistical software (Version 6.0; Stata Corp., College Station, Tex), using general estimating equations to adjust for correlations among patients in the same medical offices.

RESULTS

Approximately 95% of participating physicians and 96% of office managers completed the self-administered questionnaire, and 82% of the nonparticipating physicians completed their questionnaires. Participating and nonparticipating physicians had similar referral rates, board certification, specialty, and racial mix, but participants had a higher percentage of group practice and female physicians who had fewer years in practice, fewer office hours per week, and fewer patients aged 65 and over than nonparticipating physicians (P < .05).

Our analyses are limited to insured patients with complete follow-ups (n = 942; 71% of enrolled patients). Patients with complete data were older and had fewer depressive symptoms and fewer prior visits to psychiatrists than patients without follow-ups (P < .03), but other characteristics were similar. Primary care record reviews were performed for 98% of the patients.

Table 2 presents baseline patient characteristics. The average age was 46 years. A majority were female, white, living with a spouse or partner, educated beyond high school, employed, and had moderate household incomes. On average, patients had moderate to severe depressive symptom scores and were restricted in their usual activities 6 days in the past month. About half the patients reported 2 or more comorbid conditions. For most patients, the primary physician at baseline was the usual source of care. Almost a third of the patients had seen a mental health specialist in the past 6 months.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients with Depressive Symptoms at Waiting Room Screen (N ≥ 910)

| Measure | Percent or Average (SD) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |

| Age | 46 (14.69) |

| Female, % | 74 |

| Nonwhite, % | 13 |

| Living with spouse or partner, % | 58 |

| Employed, % | 65 |

| Education, y | 14 (2.5) |

| Annual household income, $ | 39,975 (26,675) |

| Health status | |

| Depression without pain, % | 45 |

| SCL-20 Depression Scale | 1.72 (0.65) |

| Restricted activity days due to emotional health | 6.00 (8.01) |

| Number of comorbidities | 2.79 (2.14) |

| Health care context, % | |

| Physician at waiting room screen is patient's usual source of medical care | 83 |

| Patients with visits to mental health specialist in past 6 mo before waiting room screen | 30 |

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics of the health plan, office, and physician managed care variables for patients. The health plan managedness index and the office managed care index were correlated moderately (r = .36; P = .001).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics of Managed Care Variables for Health Plans, Offices, and Physicians

| Percentile Ranges | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent, or Average (SD) | 25 | 50 | 75 | |

| Health plan indexes (n = 761) | ||||

| Plan managed care index | 36 (29) | 8 | 41 | 63 |

| In-network benefits index | 89 (9) | 85 | 91 | 96 |

| Out-of-network benefits index | 44 (34) | 0 | 56 | 73 |

| Mental health benefits index | 58 (25) | 43 | 59 | 69 |

| Mental health carve-out (yes/no), % | 31 | |||

| Office managed care index (n = 860) | 37 (33) | 8 | 19 | 57 |

| Physician managed care variables (n = 916) (Patients seeing physicians with these characteristics, %) | ||||

| Payment by salary | 64 | |||

| Productivity bonus | 58 | |||

| Financial withhold for referral | 34 | |||

| Read or used AHCPR depression guideline | 26 | |||

AHCPR, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research.

Physician Referral and Utilization of Mental Health Specialists

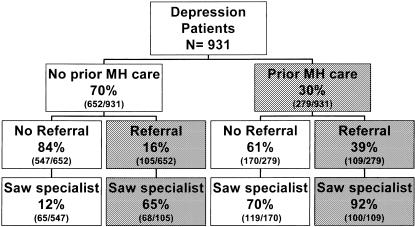

Approximately 23% of the patients were referred by their primary physicians and 38% saw a mental health specialist (Table 4). Referrals and visits to psychiatrists were lower than for other mental health specialists. Approximately 78% of patients who were referred actually saw a mental health specialist. More patients saw specialists without a referral than through referral. In regression models, the best predictors of referral and utilization of a mental health specialist were more severe depressive symptoms at baseline, prior visits to a mental health specialist, more years of education, and being younger and female. Figure 1 displays utilization patterns according to prior use of mental health specialists.

Table 4.

Primary Physician Referral and Utilization of Mental Health Specialists at 6-Month Follow-up (Unadjusted)

| Patients (N = 942), % | |

|---|---|

| Primary physician referral | |

| Referred by their primary physician to 1 or more mental health specialists | 23 |

| Referred by their primary physician to a psychiatrist | 13 |

| Utilization of mental health specialists | |

| Saw 1 or more mental health specialists | 38 |

| Saw a psychiatrist | 17 |

| Mental health specialist utilization via referral | |

| Saw 1 or more mental health specialists with at least 1 primary physician referral | 18 |

| Saw 1 or more mental health specialists without any primary physician referrals | 20 |

FIGURE 1.

Prior mental health care and access to mental health specialists.

Patients who saw a mental health specialist also had more primary physician visits for depression than patients who did not see a mental health specialist (1.93 [±SD 2.2] vs 0.98 [±SD 1.5]; P < .001). Approximately 63% of patients had chart evidence of antidepressant prescriptions and/or mood disorder before the waiting room screen, and those patients had a higher probability of referral to a mental health specialist than did patients with no chart evidence (32% vs 9%, P < .001).

For managed care by health plans, we estimated logistic regression models to look at each managed care variable and its association with each referral and specialist variable in 2 ways: first by controlling only for patient characteristics (see odds ratios for the patient (P) regression models in Table 5), and then controlling for both patient characteristics and other managed care variables (see odds ratios for full (F) models in Table 5). In the full model, the plan managed care index was associated with reduced referrals to psychiatrists: for each 10-unit increase in the index, the odds of referral to a psychiatrist decreased by 10% (OR, 0.90; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.74 to 0.99). We also found that for each 10-unit increase in the out-of-network benefits, the odds of referral to a psychiatrist increased by 1.15, which is consistent because more-managed plans generally have fewer out-of-network benefits.

Table 5.

Associations Between Managed Care Variables and Access to Mental Health Specialists at 6-Month Follow-up: Logistic Regression Odds Ratios

| Managed Care Variables | Form of Regression Model* | Patients With Primary Physician Referral to a Mental Health Specialist | Patients With a Primary Physician Referral to a Psychiatrist | Patients Who Saw a Mental Health Specialist | Patients Who Saw a Psychiatrist | Patients Who Saw a Mental Health Specialist With Primary Physician Referral | Patients Who Saw a Mental Health Specialist Without Primary Physician Referral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health plan level | |||||||

| Plan managed care index (10-unit increments)† | P | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| F | 0.90 | 0.90‡ | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1.00 | |

| In-network benefits index (10-unit increments)† | P | 1.02 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.22 | 0.74‡ |

| F | 1.34‡ | 1.10 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.48‡ | 0.90 | |

| Out-of-network benefits index (10-unit increments)† | P | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| F | 1.06 | 1.15§ | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.09 | 1.02 | |

| Mental health benefits index (10-unit increments)† | P | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| F | 0.90 | 0.90‡ | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1.00 | |

| Mental health carve-out‖ | P | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 0.87 | 0.96 | 1.02 |

| F | 0.96 | 1.24 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.98 | |

| Office level | |||||||

| Office managed care index (10-unit increments)† | P | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| F | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.00 | |

| Physician level‖ | |||||||

| Patient sees primary care physician paid by salary | P | 1.01 | 1.75 | 0.99 | 0.82 | 1.05 | 0.99 |

| F | 0.91 | 2.07 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.80 | 0.87 | |

| Patient sees primary care physician who receives productivity bonus | P | 1.26 | 1.00 | 1.43 | 1.61‡ | 1.34 | 1.30 |

| F | 1.88§ | 1.26 | 1.90§ | 1.85‡ | 1.95‡ | 1.43 | |

| Patient sees primary care physician who has a financial withhold for referrals | P | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 0.80 |

| F | 0.95 | 1.30 | 0.61 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.56‡ | |

| Patient sees primary care physician who has read or uses AHCPR depression guidelines | P | 1.38 | 1.53 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.18 | 0.85 |

| F | 1.17 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1.05 | 0.91 | |

In patient (P) regression models, the independent variables were a single managed care variable and patient covariates (baseline score of the dependent variable, sociodemographic characteristics, number of medical comorbidities, whether the primary physician was the patient's usual source of medical care, and whether the patient reported seeing a mental health specialist in the 6 months before baseline). Patients with complete data for each level were as follows: health plan level, n = 709; office level, n = 686; and physician level, n = 847. In full (F) regression models (n = 624), independent variables included all managed care variables and patient covariates (n = 624 with complete data).

The health plan and office indexes are (0–100) continous variables, and coefficients indicate the change in the dependent variable for a 10-unit change in an index (for example, a change from 50 to 60).

P < .05.

P < .01.

Mental health carve-out and the physician variables are binary (0, 1) measures.

In the full models, for each 10-unit increase of in-network benefits, the odds of referral to a mental health specialist increased by 34% (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.79), and the odds of seeing a mental health specialist with primary physician referral increased by 48% (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.97). The patient models had consistent results: each 10-unit increase of in-network benefits was associated with decreased odds of seeing a mental health specialist without referral (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.60 to 1.00). We also found that for each 10-unit increase in mental health benefits, the odds of referral to a psychiatrist decreased by 10% (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.74 to 0.99).

For managed care by offices, the office managed care index had no significant associations with referrals and utilization of mental health specialists.

For physician managed care, a productivity bonus was associated with a greater likelihood of referral to a mental health specialist, a greater likelihood of seeing a mental health specialist and seeing a psychiatrist, and a greater likelihood of seeing a mental health specialist with primary physician referral (OR range: 1.61 to 1.95). A financial withhold for referral was associated with a lower likelihood of seeing a mental health specialist without primary physician referral (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.33 to 0.97).

Based on Pseudo-R2 for logistic regression, the patient variables accounted for 0.15 of the variation in referrals, and 0.23 to 0.29 of the variation in seeing a mental health specialist or psychiatrist. After patient variables were entered into regression models, the managed care variables explained little additional variation in access to specialists.

Interaction tests provided little evidence that the managed care variables were more strongly associated with reduced referral or utilization of mental health specialists for patients with lower incomes, age over 65, or more severe depressive symptoms. However, for low-income patients, who had more depressive symptoms (higher SCL scores, 1.80 vs 1.70; P = .043) and more restricted activity days (8.2 vs 5.1; P = .001) than others, a financial withhold was associated with a lower likelihood of referral to a mental health specialist (OR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.94), while knowledge or use of AHCPR depression guidelines was associated with a greater likelihood of referral to a psychiatrist (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.09 to 7.56). For patients with previous mental health care, the odds of seeing a psychiatrist decreased by 11% for each 10-unit increase in plan managedness (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.80 to 0.98).

Among referred patients (n = 219), 46% had referrals to psychologists or master-level therapists, 19% had referrals to psychiatrists, and 35% had referrals to both. Among patients who saw 1 or more mental health specialists (n = 356), 54% saw a psychologist or master-level therapist, 12% saw a psychiatrist, and 34% saw both. Patients with referrals or visits to psychiatrists had more severe depressive symptoms and more restricted activity days at baseline than did patients with referrals or visits to other mental health specialists (P < .01).

Among referred patients, the odds of referral to a psychiatrist (versus referral to other mental health specialists) decreased by 10% for each 10-unit increase in the plan managed care index (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.00), decreased by 46% for each 10-unit increase of in-network benefits (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.82), and decreased by 18% for each 10-unit increase in mental health benefits (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74 to 0.99). Payment of primary physicians by salary was associated with greater referrals to psychiatrists (OR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.25 to 4.59). For patients who saw a mental health specialist, managed care was not associated with seeing a psychiatrist versus seeing other mental health specialists.

Health Outcomes

Table 6 describes the health status of patients at baseline and at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups. On average, most patients improved. Average SCL and restricted activity scores declined by ∼50% at the 3-month follow-up and changed little thereafter.

Table 6.

Self-reported Health Status at Waiting Room Screen and 3- and 6-Month Follow-ups: Unadjusted Descriptive Statistics

| Health Status Measure | Average at Waiting Room Screen (SD) | Average at 3-Month Follow-up (SD) | Average at 6-Month Follow-up (SD) | Average Change Score at 6-Month Follow-up (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCL-20 depression score | 1.72 (0.65) | 0.94* (0.72) | 0.91* (0.74) | 0.82 (0.74) |

| Restricted activity days due to emotional health | 6.00 (8.01) | 2.76* (6.31) | 2.67* (6.24) | 3.27 (8.69) |

Difference between average at baseline and follow-up is significant (P < .001).

Controlling for patient characteristics, we examined whether each managed care variable was associated with outcomes of care at the 3-month follow-up, and none of the managed care variables were associated with worse health outcomes.

For managed care by health plans at the 6-month follow-up, a 10-unit increase in the plan managed care index was associated with a 0.02 increase in SCL depression change scores and 0.28 days of more improvement in restricted activity due to emotional health, controlling for other managed care variables (see Table 7). More-managed plans have less out-of-network benefits, and each 10-unit decrease in out-of-network benefits was associated with 0.28 days of more improvement in restricted activity. Similarly, a 10-unit increase of mental health benefits was associated with 0.25 days of more improvement in restricted activity.

Table 7.

Associations Between Managed Care Variables and Outcomes of Care at 6-Month Follow-up: OLS Regression Coefficients

| Managed Care Variables | Form of Regression Model* | Change in SCL Depression Score | Change in Restricted Activity Days Due to Emotional Health | Patient Rating of Care from Primary Physician |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health plan level | ||||

| Plan managed care index (10-unit increments)† | P | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.06‡ |

| F | 0.02§ | 0.28§ | −0.03 | |

| In-network benefits index (10-unit increments)† | P | −0.09‡ | −0.39 | −0.08 |

| F | −0.14‡ | −0.93§ | −0.05 | |

| Out-of-network benefits (10-unit increments)† | P | −0.01 | −0.13 | 0.03 |

| F | −0.02 | −0.28§ | 0.02 | |

| Mental health benefits index (10-unit increments)† | P | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| F | 0.02 | 0.25§ | −0.01 | |

| Mental health carve-out‖ | P | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.19 |

| F | 0.04 | −0.09 | −0.12 | |

| Office level† | ||||

| Office managed care index (10-unit increments) | P | 0.02‡ | 0.09 | −0.06‡ |

| F | 0.02§ | 0.07 | 0.05§ | |

| Physician level‖ | ||||

| Patient sees primary care physician paid by salary | P | 0.03 | 0.18 | −0.15 |

| F | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.02 | |

| Patient sees primary care physician who receives productivity bonus | P | −0.03 | −0.53 | 0.20 |

| F | −0.04 | −0.38 | 0.14 | |

| Patient sees primary care physician who has a financial withhold for referrals | P | 0.08§ | −0.15 | −0.18 |

| F | 0.10 | −0.25 | −0.23 | |

| Patient sees primary care physician who has read or uses AHCPR depression guidelines | P | 0.07 | −0.17 | 0.03 |

| F | 0.01 | −0.53 | 0.18 | |

In patient (P) regression models, the independent variables were a single managed care variable and patient covariates (baseline score of the dependent variable, sociodemographic characteristics, number of medical comorbidities, whether the primary physician was the patient's usual source of medical care, and whether the patient reported seeing a mental health specialist in the 6 months before baseline). Patients with complete data for each level were as follows: health plan level, n = 709; office level, n = 686; and physician level, n = 847. In full (F) regression models (n = 624), independent variables included all managed care variables and patient covariates (n = 624 with complete data).

The health plan and office indexes are (0–100) continous variables, and coefficients indicate the change in the dependent variable for a 10-unit change in an index (for example, a change from 50 to 60).

P < .01.

P < .05.

Mental health carve-out and the physician variables are binary (0, 1) measures.

However, a 10-unit increase of in-network benefits was associated with a 0.09 decrease (or less improvement) in SCL change scores in the patient regression model, and a similar 0.14 decrease in the full regression model. A 10-unit increase of in-network benefits also was associated with less improvement in restricted activity days by almost a full day (Coefficient, −0.93).

For managed care by offices, a 10-unit increase in the office index was associated with 0.02 greater improvement in SCL change scores in the patient and full regression models.

For physician managed care, a financial withhold was associated with more improvement in SCL scores, but this association disappeared when controlling for other managed care variables.

On the basis of R2 statistics, the patient variables explained about 0.28 of the variation in SCL change scores, 0.55 of the variation in change scores for restricted activity days, and 0.04 of the variation in patient rating of care from the primary physician. After patient variables were entered into regression models, the managed care variables explained little additional variation.

When we controlled for the number of primary physician visits for depression and seeing a mental health specialist in the follow-up period, the associations between the managed care variables and outcomes remained the same. Greater primary physician visits for depression and seeing mental health specialists were associated consistently with worse health outcomes.

We found little evidence that the managed care variables were more strongly associated with worse health outcomes for patients with lower incomes, more severe depressive symptoms, age over 65, or previous use of mental health care. However, for patients under 65 or for patients with more severe depression, greater out-of-network benefits were associated with less improvement. Similarly, for patients with past use of mental health care, a productivity bonus was associated with less improvement for both outcome measures.

Patient Rating of Health Care from Primary Physician

Patient rating of health care provided by their primary physicians averaged 4.18 (±SD 1.35) at the 6-month follow-up. Controlling for patient variables, more-managed health plans were associated with lower patient ratings, but this association disappeared when controlling for other managed care variables (Table 7). Controlling for patient variables, each 10-unit increase of the office index was associated with 0.06 lower patient ratings (P = .007), and the result was almost identical when controlling for other managed care variables (P = .014). Other managed care variables were not associated with patient ratings of care from their physicians, and seeing a mental health specialist was not associated with patient ratings.

Patient and managed care variables explained a relatively small amount of the variation (8%) in patient ratings. About half of the explained variation was due to managed care variables.

Selection Bias Due to Plan Choice

Approximately 51% of the patients had a choice of 2 or more health plans. For the significant managed care and benefit indexes in the access and outcome analyses, we adjusted for potential selection bias due to choice of health plans using the 3 approaches. All plan associations were robust to the 3 types of adjustment for selection bias.

Loss to Follow-up

Using propensity analyses, we identified patients with a low versus high probability of being excluded from regression models because of missing data. We repeated the analyses for the 2 groups and generally found regression coefficients with signs and sizes similar to those in Tables 5 and 7.

DISCUSSION

We found that for all patients, managed care controls generally were not associated with a lower likelihood of referral or seeing a mental health specialist. Several explanations for this result are possible. To control costs, more-managed plans, offices, and behavioral health firms may not restrict access to mental health specialists but rather limit the intensity of mental health services by imposing controls targeting mental health specialists, such as limits on the number of covered visits, preauthorization of treatment plans, financial withholds, and lower fees.25–27 By limiting the intensity of mental health care, these controls might affect depression outcomes among patients receiving care from mental health specialists.

For low-income patients, however, a financial withhold for referral was associated with a lower likelihood of referral to a mental health specialist. The association is problematic because low-income patients were more severely depressed and reported more restricted activity days due to emotional health than higher income patients. Low-income patients may be less apt to recognize their problem as depression and more apt to perceive mental illness as carrying a stigma and, therefore, may be less likely to advocate for a referral or see a mental health specialist without referral. In fact, a financial withhold was associated with a lower likelihood of seeing a mental health specialist without referral among all depression patients. Financial withholds have less value as a cost control mechanism when they reduce access for people who are least able to pay for mental health care or to advocate for appropriate care from mental health specialists. Replication of this study in a low-income population of patients with depression is warranted.

For low-income patients, physician knowledge or use of AHCPR depression guidelines was associated with a greater likelihood of referral to a psychiatrist. Physicians who use guidelines may have characteristics or practice styles that were not measured in this study but which result in greater mental health referrals. The opposite associations for financial withholds and guidelines may explain why managed care was not associated with actual use of mental health specialists and health outcomes among low-income patients.

A third conclusion is that, controlling for patient and managed care variables, more-managed health plans were associated with reduced referrals to psychiatrists, a finding consistent with the Medical Outcomes Study.4,28 This may have occurred because more-managed plans and mental health carve-outs usually have fewer psychiatrists in their provider networks than less-managed plans.29 Reduced access to psychiatrists may be detrimental to patients with severe depression and no choice of health plans.30

Fourth, a physician productivity bonus was associated consistently with a greater likelihood of referral to a mental health specialist, seeing a mental health specialist with referral, and seeing a psychiatrist. Because more-managed offices often impose productivity requirements,31 primary physicians in these settings may have incentives to refer patients who require longer or more frequent office visits.

Turning to health outcomes, a fifth conclusion is that more-managed health plans and offices had more improvement in depressive symptoms, controlling for patient and other managed care variables. Selection bias analyses indicate that the findings are not due to less or more severely depressed patients in more-managed plans. By comparison, the Medical Outcomes Study found similar outcomes between fee-for-service and prepaid health care for patients treated by general clinicians, psychologists, and social workers.7 Among psychiatrists, who treated psychologically sicker patients, outcomes were worse in the prepaid plans, which may be due to a less-intensive treatment style among psychiatrists in the prepaid plans.7 Because depression severity predicts seeing a specialist, and both severity and less-managed plans predict seeing a psychiatrist, a randomized trial is necessary to determine whether outcomes differ across provider types and managed care settings.

A sixth conclusion is that plan benefits are associated with access to mental health specialists and health outcomes. Controlling for patient and managed care variables, greater in-network benefits were associated with greater referrals and use of mental health specialists, but less improvement in health outcomes. In contrast, greater mental health benefits were associated with fewer referrals to psychiatrists and more improvement in restricted activity days due to emotional health.

The reasons for these inconsistent associations are unclear, for they are not explained by selection bias from more severely depressed patients choosing plans with greater benefits.

Controlling for primary care visits and seeing a mental health specialist in the follow-up period did not alter these findings. In fact, greater primary physician visits for depression and seeing a mental health specialist were associated with less improvement, probably because patients with more primary care and mental health specialist visits had more severe depressive symptoms at baseline. Patients with different plan benefits, or their primary physicians, may simply have unmeasured preferences for referral or seeing psychologists or master-level therapists rather than psychiatrists. Greater in-network benefits may have resulted in greater use of necessary and unnecessary general medical services, which could lead to worse depression outcomes through adverse side-effects of medical treatment.32

Alternately, greater benefits increase utilization and costs,33 which increase the financial risks of health plans (under fee-for-service reimbursement) and provider groups (under capitation). To control these risks, plans and provider groups may restrict access to higher-cost psychiatrists, and we found that among referred patients, greater in-network and mental health benefits were associated with reduced referrals to psychiatrists.

High-benefit plans, such as HMOs and plans with a mental health carve-out, also may improve access but control costs by limiting covered visits to mental health specialists.25,34 At the 3-month follow-up, plan benefits were not associated with health outcomes, probably because in the short-run patients in low versus high benefit plans had a similar probability of seeing a mental health specialist and a similar number of visits.25 Between the 3- and 6-month follow-ups, however, the health status of patients with higher in-network benefits changed little, while the health status of patients with lower in-network benefits improved. Patients in high-benefit plans may have improved less in this period because the plan or provider group limited mental health visits to control their long-run costs.

A seventh conclusion is that mental health carve-outs were not associated with reduced access to mental health specialists, including psychiatrists,35 and health outcomes. However, bivariate analyses showed that carve-out plans had patients with less-severe depressive symptoms at baseline. Controlling for baseline differences, no association between carve-outs and health outcomes was detected.

Finally, after controlling for patient and managed care variables, patients in more-managed offices had lower ratings of the care provided by their primary physicians, which is consistent with previous studies. No association was detected for more-managed plans, suggesting that the office—and not the health plan—is the source of the lower patient ratings, probably because the office is “closer” to the patient-physician relationship.36,37

Limitations and Conclusions

Our findings are limited to our sample of mainly middle-income, Caucasian adults with depressive symptoms in the private practices of consenting family practitioners, general internists, and general practitioners in the Seattle area. Primary physicians in small practices were less likely to participate, and our findings may not apply to patients seen in those settings. Another limitation is that our study does not address managed care controls targeting mental health specialists, which may affect the intensity of mental health services and outcomes.

The Seattle patients had a relatively even distribution of traditional indemnity health plans, preferred provider organizations, point of service plans, and health maintenance organizations, and were seen in a variety of primary care organizations, ranging from solo practice to integrated delivery systems. Our findings may not be generalizable to other cities with different mixes of managed care and delivery systems.

Another limitation of observational studies is that patients and physicians are not randomized to health plans and medical offices, so our results may be influenced by selection bias. We used several methods of correcting for selection bias due to choice of health plans, and those results were generally consistent with our basic findings. Because of the numerous statistical tests, some managed care associations may be due to chance.

Finally, 29% of the consenting adults who did not complete the 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-ups had more severe depressive symptoms at baseline than did those with complete follow-ups. For patients with follow-ups, 57% of the patients had baseline SCL scores ≥1.70, which has been reported as the best cut score for major depression.38,39 If all patients had major depression, more referrals to mental health specialists would likely occur, and managed care associations might be different than reported in our study.

We conclude that in our sample, managed care was generally not associated with reduced access to mental health specialists among primary care patients with depressive symptoms. However, more-managed health plans were associated with reduced referrals to psychiatrists, and for low-income patients, a financial withhold for referral was associated with reduced referrals. In contrast, a physician productivity bonus was associated with greater access to mental health specialists. Patients had similar or greater improvement in more-managed plans and offices but at the expense of lower patient ratings of care provided by their primary physicians.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank and acknowledge several people who made important contributions to the study. First and foremost, we wish to thank the patients, physicians and office managers who participated in the study. Rosie Pavlov, John Tarnai and Donald Dillman, affiliated with the Social and Economic Sciences Research Center at Washington State University, managed the patient follow-up surveys. Naihua Duan and Stephen Shortell provided consultant support for the selection bias analysis and the design of study instruments, respectively. Amy Roussel, an AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, formerly AHCPR) post-doctorate fellow, contributed to all phases of study design and data collection. Cornelia Ulrich designed and processed the physician and office manager questionnaires. Megan Dwight and Tracy Laidley assisted in physician recruitment. Marina Madrid managed patient recruitment in physician offices. Shelby Tarutis, Johnny Jeans, Rick Orsillo, Georgia Galvin, Alisa Katai, Massooma Sherzoi, Kristie Marbut, Kathryn Molinar, and Carolyn Hale supported data collection and study administration. Alice Gronski helped prepare the manuscript.

Funding support was received from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (formerly AHCPR) Grant No. HS06833.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:405–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginzberg E. Managed care and the competitive market in health care: what they can and cannot do. JAMA. 1997;277:1812–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wells KB, Sturm R, Sherbourne CD, Meredith LS. Caring for Depression. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulberg HC, Katon WJ, Simon GE, Rush AJ. Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1121–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulberg HC, Katon WJ, Simon GE, Rush AJ. Best clinical practice: guidelines for managing major depression in primary medical care. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 7):19S–26S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers WH, Wells KB, Meredith LS, Sturm R, Burnam A. Outcomes for adult outpatients with depression under prepaid or fee-for-service financing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:517–25. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190019003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grembowski DE, Cook K, Patrick DL, Roussel AE. Managed care and physician referral. Med Care Res Rev. 1998;55:3–31. doi: 10.1177/107755879805500101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassirer JP. Access to specialty care. New Engl J Med. 1994;331:1151–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410273311709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grembowski D, Diehr P, Novak LC, et al. Measuring the managedness and covered benefits of health plans. Health Serv Res. 2000;35:707–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist: a measure of primary symptom dimensions. In: Pichot P, editor. Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology: Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry. Basel, Switzerland: Kargerman; 1974. pp. 79–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, LeResche L, Kruger A. An epidemiologic comparison of pain complaints. Pain. 1988;32:173–83. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katon W, Lin E, Von Korff M, et al. The predictors of persistence of depression in primary care. J Affect Disord. 1994;31:81–90. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg HI, Wagner EH, Fihn SD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of CQI teams and academic detailing: can they alter compliance with guidelines? Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24:130–42. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE, Jr, Bayliss MS, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR. Differences in 4-year health outcomes for elderly and poor, chronically ill patients treated in HMO and fee-for-service systems: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1996;276:1039–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hays RD, Shaul JA, Williams SL, et al. Psychometric properties of the CAHPS 1.0 survey measures. Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. Med Care. 1999;37:22–31. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank RG, Huskamp HA, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP. Some economics of mental health ‘carve-outs.’. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:933–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100081010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rush AJ, Golden WE, Hall GW, et al. Depression in Primary Care, Vol 1 and 2: Clinical Practice Guideline Number 5. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. AHCPR Publication No. 93–0551. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells KB, Rogers W, Burnam MA, Greenfield S, Ware JE., Jr How the medical comorbidity of depressed patients differs across health care settings: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1688–96. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.12.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brach C, Sanches L, Young D, et al. Wrestling with typology: penetrating the “black box” of managed care by focusing on health care system characteristics. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 2):93S–115S. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057002S06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forrest CB, Glade GB, Starfield B, Baker AD, Kang M, Reid RJ. Gatekeeping and referral of children and adolescents to specialty care. Pediatrics. 1999;104:28–34. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells KB, Burnam A, Rogers W, Hays R, Camp P. The course of depression in adult outpatients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:788–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100032007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware JE, Brook RH, Rogers WH, et al. Comparison of health outcomes at a health maintenance organization with those of fee-for-service. Lancet. 1986;1:1017–22. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score (in applications) J Am Statistical Assoc. 1984;79:516–24. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norquist GS, Wells KB. How do HMOs reduce outpatient mental health care costs? Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:96–101. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Sturm R, Cuffel BJ. The impact of prior authorization on outpatient utilization in managed behavioral health plans. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:182–95. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grazier KL, Pollack H. Translating behavioral health services research into benefits policy. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:53–71. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057002S04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sturm R, Meredith LS, Wells KB. Provider choice and continuity for the treatment of depression. Med Care. 1996;34:723–34. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheffler R, Ivey SL. Mental health staffing in managed care organizations: a case study. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:1303–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.10.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whooley MA, Simon GE. Managing depression in medical outpatients. New Engl J Med. 2000;343:1942–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott RA, Aiken LH, Mechanic D, Moravcsik J. Organizational aspects of care. Milbank Q. 1995;73:77–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells KB, Manning WG, Valdez RB. The effects of insurance generosity on the psychological distress and psychological well-being of a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:315–20. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810040021004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newhouse JP Insurance Experiment Group. Free For All? Lessons from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sturm R, Jackson CA, Meredith LS, et al. Mental health utilization in prepaid and fee-for-service plans among depressed patients in the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Serv Res. 1995;30:319–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sturm R, Klap R. Use of psychiatrists, psychologists, and master's-level therapists in managed behavioral health care carve-out plans. Psychiat Serv. 1999;50:504–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dudley RA, Miller RH, Korenbrot TY, Luft HS. The impact of financial incentives on quality of care. Milbank Q. 1998;76:649–86. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerr EA, Mittman BS, Hays RD, et al. Managed care and capitation in California: how do physicians at financial risk control their own utilization? Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:500–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-7-199510010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mulrow C, Williams J, Jr, Gerety M, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Am Coll Physicians. 1995;122:913–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-12-199506150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hough R, Landsverk J, Stone J, et al. Comparison of Psychiatric Screening Questionnaires for Primary Care Patients. Bethesda, Md: National Instutute of Mental Health; 1983. Final report for NIMH Contract #278–81–0036. [Google Scholar]