Abstract

CONTEXT

Providing home care in the United States is expensive, and significant geographic variation exists in the utilization of these services. However, few data exist on how well physicians and home care providers communicate and coordinate care for patients.

OBJECTIVE

To assess communication and collaboration between primary care physicians (PCPs) and home care clinicians (HCCs) within 1 primary care network.

DESIGN

Mail survey.

SETTING

Boston.

PARTICIPANTS

Sixty-seven PCPs from 1 academic medical center–affiliated primary care network and 820 HCCs from 8 regional home care agencies.

MEASUREMENTS

Provider responses

RESULTS

Ninety percent of PCPs and 63% of HCCs responded. The majority (54%) of PCPs reported that they only “rarely” or “occasionally” read carefully the home care order forms sent to them for signature. Further, when asked to rate their prospective involvement in the decision making about home care, only 24% of PCPs and 25% of HCCs rated this as “excellent” or “very good.” Although more HCCs (79%) than PCPs (47%) reported overall satisfaction with communication and collaboration, 28% of HCCs felt they provided more services to patients than clinically necessary.

CONCLUSIONS

PCPs from 1 provider network and the HCCs with whom they coordinate home care were both dissatisfied with many aspects of communication and collaboration regarding home care services. Moreover, neither group felt in control of home care decision making. These findings are of concern because poor coordination of home care may adversely affect quality and contribute to inappropriate utilization of these services.

Keywords: home care, primary care, communication, integrated health care, resource utilization

Since coverage of home care services was expanded in 1989,1 Medicare expenditures for home care rose 25% annually from 1990 ($3.7 billion) to 1997 ($17.8 billion).2 Although Medicare spending for home health care declined following the passage of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, the United States General Accounting Office remains concerned that the prospective payment system ultimately may not restrain spending for home care services.3

Improving the efficiency of home care will probably be complicated, however. Unlike care in hospitals, where providers physically work together and communicate through a common medical record, care of patients in their homes requires collaboration and communication between physicians and home care providers who generally do not physically work together. Furthermore, physicians and home care nurses maintain separate medical records for patients they have in common.

Although the original aim of home care was to ease the transition from hospital to home, a review of Medicare utilization patterns found that 78% of home health care visits took place more than a month after a hospital discharge and that 43% of patients visited had no antecedent hospitalization in the prior 6 months.4 Significant geographic variation exists in home care expenditures,4,5 and the evidence about whether increasing home care utilization decreases inpatient utilization is contradictory.4,6,7

Previous research has focused on home care utilization patterns. Few studies have examined the home health care system from the perspective of the physician and home care clinician (HCC) who collaborate in providing home care services. One study assessing family doctors' understanding of palliative care services in the United Kingdom found physicians wishing for improved communication and a stronger liaison with these home care services.8

The little available evidence suggests that physicians do not fully appreciate their role in managing home care. As Welch observed: “…physicians may view their role as simply signing the required form and may be only vaguely aware that it is they, not nurses, who authorize home care.”4 While physicians are legally responsible for ordering and monitoring home care services, management of patients receiving home care has not traditionally been a primary clinical focus nor has it been emphasized in medical education. Yet, communication between physicians and HCCs is critical to providing integrated health care to patients, especially as pressures mount to shorten hospital stays in managed care systems.9

To determine the effectiveness of systems for managing home care services within a large primary care network, we surveyed primary care physicians (PCPs) and the HCCs with whom they share patients, asking each to assess the efficiency of communication and collaboration from their vantage point.

METHODS

This study was performed in the Fall of 1997 at Brigham and Women's Hospital, a Boston academic medical center affiliated with Harvard Medical School, and at 8 home care agencies to whom Brigham and Women's Hospital PCPs refer patients.

Sixty-seven PCPs within the Brigham and Women's Physician Hospital Organization were asked to complete a confidential survey (see Appendix at http://www.blackwellscience.com/jgi). Up to 3 follow-up surveys were sent to nonrespondents. To encourage responses, each of 820 HCCs (defined as any licensed clinician caring for patients in their home, [nurses and physical therapists e.g., but not home health aides, etc.]) was promised confidentiality and anonymity. For logistical reasons, HCCs were sent only 1 mailing, but were encouraged by their agency supervisors to complete the survey.

Unless otherwise noted, responses to survey questions were scored using a 5-point Likert scale where 5 = “excellent,” 4 = “very good,” 3 = “good,” 2 = “fair,” and 1 = “poor.” Results are presented as mean point scores, the percent of respondents choosing a given category, or as a trinary outcome where the 5-point scale was collapsed into 3 categories (very good/excellent, good, and fair/poor).

To quantify overall satisfaction, we calculated the mean response to the series of questions assessing satisfaction with communication and participation in decision making (questions 1 to 9 for HCCs, and questions 1 to 6 for PCPs). In χ2 analyses, these summary satisfaction scores were dichotomized (1 to 3.0 = not satisfied; 3.1 to 5.0 = satisfied).

The survey instrument was developed on the basis of our clinical experience. Tests of internal consistency were similar for the satisfaction questions in both the PCP and HCC surveys (Cronbach coefficient α = 0.85 for each).

In our home health care system, physicians choose a home health agency on the basis of the patient's clinical needs and the geographic area served by the agency. HCCs are employed by home heath care agencies (not Brigham and Women's Hospital) and are assigned to a patient by the agency. Under physicians' orders, HCCs provide care to patients in their homes, keeping the ordering physician informed in writing or by telephone. All medical orders must be written, but most orders are either written by nurses in the physician's office or written by HCCs and then sent to the physician to be signed. Physicians in our system rarely make house calls and rarely meet with HCCs. On the basis of our clinical experience, we hypothesized that neither PCPs nor HCCs would be satisfied with the current means of communication.

Correlates of overall satisfaction and the strength of other associations were determined using χ2 analysis. All P values were 2-tailed.

RESULTS

Survey Sample

Of 67 eligible PCPs, 60 (90%) responded to the survey. Respondents had been in practice for an average of 17.5 years and had a mean age of 43.4 years. Fifty percent practiced “off campus” in the community and 50% were women. Characteristics of responding physicians did not differ significantly from PCPs as a whole with respect to age, gender, or number of years in practice. Of 820 home care providers surveyed, 514 (63%) responded. Demographic information was obtained from our hospital administrative databases for PCPs. Demographic data were not collected from HCCs because these questions were not part of the survey instrument and we did not have access to provider databases for HCCs who came from home care agencies outside of our hospital network.

Satisfaction with Communication

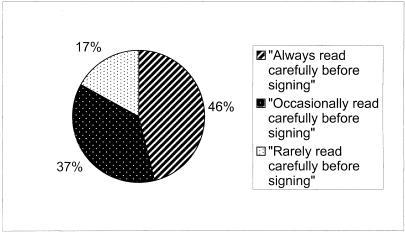

Treatment renewal orders and confirmation of verbal orders often occur by having the PCP sign a written form sent from the HCC to the physician for review and signature. We asked PCPs how thoroughly they read these forms before signing (PCP survey question 7). Fifty-four percent of PCPs surveyed “rarely” or “occasionally” read the forms carefully before signing; less than half (46%) of respondents claimed they “always” read forms carefully before signing (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Primary care physician response to the question: “How thoroughly do you read the forms sent from the home health agencies for your signature?”

More HCCs (74%) than PCPs (47%) reported overall satisfaction with communication between PCPs and HCCs. Among physicians, overall satisfaction was higher in the subset of PCPs who reported “always” reading the forms sent from HCCs before signing them (70% of PCPs satisfied), compared to PCPs who “rarely” or “occasionally” read these forms before signing (27% of PCPs satisfied) (P < .001 for comparison).

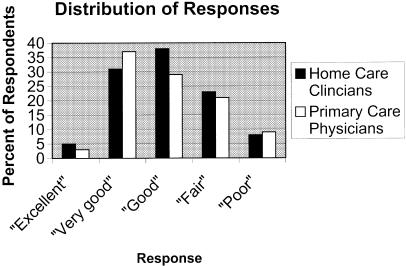

When asked to rate the ease of contacting a patient's home health provider to discuss an urgent patient care matter (PCP survey question 1), physicians were only moderately satisfied (mean rating = 2.97 on a 5-point scale where 5 = “excellent” and 1 = “poor”). Although the mean was above the midpoint and the distribution was positively skewed, only 38% of PCPs rated this as “very good” or “excellent,” 31% rated this as “good,” and another 31% rated this “fair” or “poor.” Similarly, HCCs were only moderately satisfied with the ease of contacting a patient's physician to discuss an urgent patient care matter (HCC survey question 1). The mean response was 3.0, but 31% of HCCs reported the ease of communication to be “fair” or “poor,” 38% gave this a “good” rating, and 31% rated it “very good” or “excellent” (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Primary care physician (PCP) and home care clinician (HCC) response to the question: “Rate the ease of contacting the (PCP/HCC) to discuss an urgent patient care matter.”

Despite the fact that many HCCs expressed dissatisfaction with the ease of contacting a physician when needed, most PCPs felt that HCCs called them “about the right amount” (63%) or “slightly too often” (26%). Only 11% of PCPs indicated that they were contacted “slightly too infrequently” (PCP survey question 14). Viewed from the opposite perspective, HCCs report that they call more frequently than they believe to be necessary. Only 18% of home care clinicians felt that they had “clearly defined parameters… regarding appropriate reasons for telephone calls” (HCC survey question 14). When asked to estimate how clearly defined parameters would affect the number of telephone calls to physicians, 74% of HCCs predicted that the frequency of calls to PCPs would decrease (HCC survey question 14b).

Control over Utilization of Home Care Services

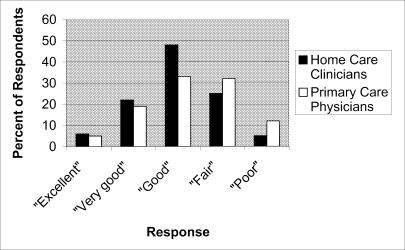

Medicare and other insurers require a physician's order for any home care service. However, many PCPs in our survey felt that they do not control home care decision making. When PCPs were asked to rate the degree to which they are involved prospectively in decision making about starting or continuing home care services (PCP survey question 6), only 24% rated this as “very good” or “excellent.” A third (32%) rated this “good,” and 44% of PCPs rated this “fair” or “poor,” (Fig. 3). We found a positive association (although one that did not reach statistical significance) between the frequency with which PCPs read written communications from HCCs and the level of involvement in home care decision making reported by PCPs (P = .09 by χ2). PCPs who reported a “very good” or “excellent” level of involvement in home care decision making were more likely to report “always” reading the medical order forms from HCCs before signing (64%), and less likely to report “occasionally” reading these forms (29%) or “rarely” reading these forms before signing them (7%).

FIGURE 3.

Responses of primary care physicians and home care clinicians when asked to “Rate the degree to which [they] are involved prospectively in decision making about starting or continuing [home care] services.”

HCCs also feel they do not control home care decision making. When rating the degree to which they are involved prospectively in decision making about continuing home services (HCC survey question 8), only 28% of HCCs rated this as “very good” or “excellent.” Almost a third of HCCs rated this “fair” or “poor,” and 42% gave this a “good” rating (Fig. 3). Taking the PCP and HCC responses together, these data indicate that neither PCPs nor HCCs feel ownership of the home care decision-making process.

Our findings also suggest that the current home health care system may be providing more services than are clinically indicated in some cases. When asked to rate the clinical necessity of the “amount and duration of home care services provided to patients” (HCC survey question 19), the majority of HCCs (59%) felt that the intensity of services was “about right.” A minority (13%) indicated that the intensity was either “slightly less” or “much less” than clinically necessary. However, 28% of home health clinicians indicated that they provided a level of service that was “much more” or “slightly more” than clinically necessary.

Potential Impact of Better Communication

We noted that HCCs who reported good communication with PCPs were more likely to report overutilization of home care services. Among the 385 HCCs reporting relative ease in contacting PCPs, 124 (32%) stated that they provided more clinical services than they believed to be necessary. In contrast, only 27 (22%) of the 122 HCCs claiming difficulty contacting PCPs felt they provided more clinical services than patients needed (P = .03). Further, HCCs reporting better communication from the PCP after a patient's clinic visit were more likely to report overutilization of home care services (32%) than HCCs reporting poorer communication after a patient's office visit (18%; P = .01). These associations raise the possibility that PCPs may be driving what some HCCs perceive to be excessive home care services utilization.

Improving Communication

A high proportion of both physicians (80%) and home care clinicians (90%) thought that access to a common electronic record and the ability to communicate by e-mail would be “extremely” or “moderately” useful (HCC survey question 20; PCP survey question 19). However, the 2 groups differed on the potential benefits of clinical pathways or care map protocols: 64% of physicians, but only 38% of HCCs agreed with a statement that these could “enhance… the quality and efficiency of home care” (HCC survey question 16; PCP survey question 17). Ninety percent of HCCs supported case conferencing on complex cases rather than pathways as a means of improving quality and efficiency (HCC survey question 17).

DISCUSSION

The role of home care in the United States has evolved from its initial purpose of providing a transition from hospital to home. Market forces and new therapies, such as treatment of deep-venous thrombosis with low-molecular-weight heparin,10 are moving care from the expensive acute hospital into the less expensive non-acute setting.11,12 In response to the dramatic rise of Medicare home care expenditures in the early and mid-1990s, the Health Care Financing Administration (now known as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) introduced a prospective payment system that creates an incentive for home care agencies to become more efficient. However, the effectiveness and the efficiency of systems enabling physicians and HCCs to collaboratively care for home-bound patients has not has not been well studied and remains poorly understood. We surveyed a network of PCPs and regional HCCs to get both groups' perspectives regarding the effectiveness of communication and collaboration between physicians and HCCs.

Despite the acknowledged importance of continuity and the coordination of care,13–17 we found that neither PCPs nor HCCs felt they were in control of home care. Most PCPs reported that they were not satisfied with their prospective involvement in decision making about home care, despite the fact that it is their legal responsibility to order and oversee home care services. An underlying problem appears to be inadequate means of communication. Only a minority of PCPs in our study claimed that they “always” read carefully written communications from HCCs before signing to authorize home care orders. Most HCCs also reported a low level of involvement in home care clinical decision making. In summary, the home care process appears leaderless. Neither doctors nor nurses feel they are in charge of home care.

Although there are few prior studies in this area, these findings resonate with an assessment of the United Kingdom's National Health Service in which the lack of cross-boundary teamwork was identified as an obstacle to providing truly seamless care for patients moving between primary and secondary care.18

We found, in addition to poor communication, subjective evidence of overutilization. Twenty-eight percent of HCCs reported that the amount and duration of home care services provided to patients was more than clinically necessary. We were surprised to find that HCCs who reported better communication with PCPs were more likely to report overutilization of home care services. This association may result from the relative inexperience of many physicians in managing patients at home. Trained in office and inpatient settings in which they can interview and examine patients, some internists may not feel comfortable managing patients through HCCs and compensate by ordering more home care monitoring. If confirmed in other studies, this finding suggests a need for enhanced physician education in this domain.

Facing increasing economic pressures to be productive in the office, PCPs who already do not routinely read home care order forms are unlikely to start reading these forms with the current system of communication. We have observed a mismatch between the amount and type of patient information generated by HCCs and that found useful by PCPs in managing these patients. This discrepancy may exist because home care is the raison d'etre for HCCs, who want to communicate as much information as possible to PCPs. For PCPs, on the other hand, home care is but a small portion of their clinical responsibilities, and processing this volume and type of information is difficult to integrate efficiently into clinical practice. The current means of communication is not facile enough to allow HCCs and PCPs to have truly interactive communication, and thus the system is, at times, both inefficient and ineffective. A high proportion of PCPs and HCCs in this survey felt that communicating via electronic mail or sharing clinical information through a common electronic medical record or interface would be clinically useful. Further study would be necessary to determine if computerization of the process, although feasible given the increasing ubiquity of the Internet, could actually improve communication. Medicare's decision to reimburse physicians for supervision of home care will make this work more financially attractive as well.

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. These findings from 1 urban academic medical center–affiliated primary care network and 8 local visiting nurse agencies may not be generalizable to other networks or agencies. Although mailing written orders to physicians for their review and authorizing signature is standard practice, communication systems may differ in other geographic areas and communication practices may differ between different types of home care clinicians. Also, the start of Medicare's prospective payment system for home care coincided with our study. Prospective payment has constrained home care utilization, but the means of communication between PCPs and HCCs—the focus of this study—remains largely unaffected by this modification in reimbursement methodology. Finally, for logistical reasons, HCCs only received 1 survey mailing while PCPs received 2 follow-up mailings. This could be a source of bias when comparing the levels of satisfaction among HCCs and PCPs, because people who responded after the first mailing may be more or less satisfied than those who only responded to later mailings.

Despite the limitations of this study, the shortcomings in both communication and collaboration identified in this investigation are of concern in that they may be widespread within our health care system. Fortunately, there are obvious strategies available to improve communication and the coordination and leadership issues. Further research is necessary to determine if problems of communication and collaboration exist in other home care systems, to assess their impact on the quality of home care, and to evaluate strategies to improve the involved systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the leaders of the Home Care Collaborative Practice Working Group for their insights into the working relationships between physicians and home care providers and for their efforts in the collection of these survey data: Joanne Kaufman, RN (Visiting Nurse Association of Boston), Linda Perlmutter (Health Pathways of New England), and Joan Jennings, RN (MGH/Spaulding Home Health Agency).

APPENDIX

Home Health Care Clinician Survey Interacting with Physicians

| Please rate the following based on your experience collaborating with physicians: Please circle one number for each item to indicate your response | |||||

| Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair | Poor | |

| 1. Ease of contacting your patient's MD to discuss an urgent patient care matter | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2. Ease of contacting a covering MD, when the primary care MD is unavailable | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 3. Usefulness of the written information about the patient provided to you by MD office(on initial referral) | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 4. Ease of getting 485's(certification/plan of care) and additional orders/med change orders signed and returned in a prompt manner | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 5. Usefulness of the written information about the patient provided to you by MD office on returned 485's or on other written forms | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 6. MD understanding of Medicare requirements re: patient being homebound and needing skilled services | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 7. MD communication with you after a patient has visited MD office(explaining change in status or treatment plan) | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 8. The degree to which you are involved prospectively in decision making about continuing home services | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 9. The degree to which MD's clearly express prognosis, desired goals/outcomes and number of visits for patients | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| For questions 10-14: Please check only one box | |||||

| ______________________________ | |||||

| 10. If we had greater coordination with physicians, do you feel that some inpatient re-admissions and ER visits could be avoided without compromising quality or patient outcomes? | |||||||||

| [] Yes | [] No | [] Unsure | |||||||

| 10b. If “yes”, please estimate what percentage of ER visits or inpatient re-admissions might be avoided | |||||||||

| []0% | []1-2% | []3-4% | []5-10% | []11-15% | []16-20% | []21-30% | []31-40% | []41-50% | []51-60% |

| ______________________________ | |||||||||

| 11. If we had greater coordination with physicians, do you feel that some patients could be discharged sooner from the acute care hospital to home health care without compromising quality or patient outcomes? | |||||||||

| [] Yes | [] No | [] Unsure | |||||||

| 11b. If “yes”, please estimate what percentage of patients could be discharged to home care one day earlier | |||||||||

| []0% | []1-2% | []3-4% | []5-10% | []11-20% | []21-30% | []31-40% | []41-50% | []51-70% | []71-100% |

| ______________________________ | |||||||||

| 12. Once a patient is at home receiving services, home care clinicians often make suggestions regarding types and duration of home therapies/services for patients. What percentage of the time do physicians accept your recommendations? | |||||

| []0-10% | []11-25% | []26-40% | []41-60% | []61-80% | []81-100% |

| ______________________________ | |||||

| 13. How important do you think it is for a patient to have a continuity relationship with one home health clinician? (as opposed to being followed by a series of different home health clinicians) | |||

| [] extremely important | [] moderately important | [] slightly important | [] not important at all |

| ______________________________ | |||

| 14. Do you feel that clearly defined parameters are established by physicians regarding appropriate reasons for telephone calls? | ||||

| [] Yes (skip to question 15) | [] No | [] Unsure | ||

| 14b. If physicians defined clear parameters regarding when to call them, do you think the amount of phone calls you make to physicians would: | ||||

| [] Decrease a little | [] Decrease a lot | [] Stay the same | [] Increase a lot | [] Increase a little |

| ______________________________ | ||||

| Please indicate whether you agree or disagree with the following statements about our current system for working with physicians:Please circle one number for each item to indicate your response: | |||||

| Strongly Agree | Agree Somewhat | Neither Agree nor disagree | Disagree Somewhat | Strongly Disagree | |

| 15. MD's (or their designated staff) promptly update home care clinicians regarding issues or changes which impact delivery of home care services | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 16. Quality and efficiency of home care delivery could be enhanced with greater use of clinical pathways/care maps for specific diagnosis | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 17. Case conferencing on complex cases(of large group practices with whom we work) would be helpful to us to improve outcomes for our patients | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 18. Having general standardized parameters about when to call physicans re: blood glucose, BP level, etc. would make patient management easier | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| ______________________________ | |||||

| 19. Overall, you feel that the amount and duration of home care services provided to patients is: | |||||

| [] much more than clinically necessary | |||||

| [] slightly more than clinically necessary | |||||

| [] about right | |||||

| [] slightly less than clinically necessary | |||||

| [] much less than clinically necessary | |||||

| ______________________________ | |||||

| 20. If it were possible to provide home health practitioners with electronic access to patient records and e-mail access to physicians, how useful do you think this would be? | |||||

| [] extremely useful | [] moderately useful | [] slightly useful | [] not important at all | ||

| ______________________________ | |||||

| 21. Please share something POSITIVE about your experience interacting with MD's while caring for patients at home:________________________________________________ | |||||

| ______________________________ | |||||

| 22. Please share something NEGATIVE about your experience interacting with MD's while caring for patients at home:________________________________________________ | |||||

| ______________________________ | |||||

Physician Satisfaction With Home Care Services

| BWPHO physician questionnaire | ||||||

| Please rate the following based on your experience with home care services:Please circle one number for each item to indicate your response | ||||||

| Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair | Poor | Does Not Apply | |

| 1. Ease of contacting your patient's home health provider to discuss an urgent patient care matter | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| 2. Ease of cooordinating home health services for your patients | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| 3. Usefulness of the written information provided to you from home health providers | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| 4. Commitment to continuity of care (one provider assigned to your patient over time) | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| 5. Ease of monitoring your patient's progress as a result of home care services | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| 6. The degree to which you are involved prospectively in decision making about starting or continuing services | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| For questions 9-12: Please check only one box | ||||||

| ______________________________ | ||||||

| 7. On average, how thoroughly do you read the forms sent from the home health agencies for your signature: | |

| [1] I always read each carefully before I sign | |

| [2] I occasionally read the forms carefully before I sign | |

| [3] I rarely read the forms carefully before I sign | [8] Other____ |

| ______________________________ | |

| 8. If we had greater coordination with home health agencies facilitating closer management of our patients at home, do you feel that we could avoid some inpatient admissions without compromising quality or patient outcomes? | |||

| [1] Yes | [2] No | } | |

| [8] Unsure | Skip to question #10 | ||

| ______________________________ | |||

| 9. If you answered “yes” to 8(above): What percentage of inpatient admissions do you think might be prevented if we had greater coordination with home care providers? | ||||||||

| [1]0% | [2]1-5% | [3]6-10% | [4]11-15% | [6]16-20% | [7]21-25% | [8]26-30% | [9]31-40% | [11]41-50% |

| ______________________________ | ||||||||

| 10. If we had greater coordination with home health agencies facilitating closer management of our patients at home, do you feel that we could discharge some inpatients home sooner than we currently do without compromising quality or patient outcomes? | |||

| [1] Yes | [2] No | } | |

| [8] Unsure | Skip to question #12 | ||

| ______________________________ | |||

| 11. If you answered “yes” to 10 (above): What percentage of your patients would you estimate could be discharged from the hospital a day earlier if we had greater coordination with home care agencies? | ||||||||||

| [1]0% | [2]1-5% | [3]6-10% | [4]11-20% | [5]21-30% | [6]31-40% | [7]41-50% | [8]51-60% | [9]61-70% | [10]71-85% | [11]86-100% |

| ______________________________ | ||||||||||

| 12. Once patient is at home receiving services, providers and therapists often make suggestions regarding types and duration of home therapies for your patients. What percentage of the time do you modify, change, or specify additional orders beyond those suggested by the home care providers? | ||||||||||

| [1]0% | [2]1-5% | [3]6-10% | [4]11-20% | [5]21-30% | [6]31-40% | [7]41-50% | [8]51-60% | [9]61-70% | [10]71-85% | [11]86-100% |

| ______________________________ | ||||||||||

| 13. How important is it for your patients to have a continuity relationship with one home health provider? | |||

| [1] extremely important | [2] moderately important | [3] slightly important | [4] not important at all |

| ______________________________ | |||

| 14. Regarding the clinical appropriateness of telephone calls from home health providers, do you feel you get called: | ||||

| [1]much too often | [2]slightly too often | [3]about the right amount | [4]slightly too infrequently | [5]much to infrequently |

| ______________________________ | ||||

| 15. On average, how many calls from home health providers do you personally receive a week? | |||||||

| [1]0-1 | [2]2-3 | [3]4-5 | [4]6-10 | [5]11-15 | [6]16-20 | [7]21-30 | [8]more than 30 |

| ______________________________ | |||||||

| Please indicate whether you agree or disagree with the following statements about our current system for working with home care agencies:Please circle one number for each item to indicate your response: | |||||

| Strongly Agree | Agree Somewhat | Neither Agree nor disagree | Disagree Somewhat | Strongly Disagree | |

| 16. Home care providers anticipate problems and are pro-active in the management of patients | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 17. Quality and efficiency of home nursing care could be enhanced with greater use of protocols and pathways for specific diagnoses | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 18. The number of different home health nurses currently following my patients at home is greater than necessary making communication about patient management inefficient | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| ______________________________ | |||||

| 18. In the future, it may be possible to provide home health practitioners with electronic access to BWH records allowing them to record notes, access information, send you e-mail etc. How useful do you think this addition would be? | |||||||||||

| [1] Extremely Useful | [2] Moderately Useful | [3] Slightly Useful | [4] Not Important at All | ||||||||

| ______________________________ | |||||||||||

| 19. In general, who in your office handles initial telephone calls from home health providers? | |||||||||||

| [1] MD | [2] RN | [3]Nurse Practitioner/Physician's assistant | |||||||||

| ______________________________ | |||||||||||

| 20. Please share something POSITIVE about your experience with home health care services at BWH: | |||||||||||

| ______________________________ | ______________________________ | ______________________________ | |||||||||

| 21. Please share something NEGATIVE about your experience with home health care services at BWH: | |||||||||||

| ______________________________ | ______________________________ | ______________________________ | |||||||||

Please Return to:David Fairchild, M.D., PBB-Admin-4 in attached envelope

REFERENCES

- 1.Helbing C, Sangl JA, Silverman HA. Home health agency benefits. Health Care Financ Rev. 1992;(Annual Supplement):125S–48S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States General Accounting Office. Medicare Home Health Care: Prospective Payment System Will Need Refinement as Data Become Available. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. Gao Letter Report. 4/07/2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States General Accounting Office. Medicare Home Health Care: Prospective Payment System Could Reverse Recent Declines in Spending. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. GAO Letter Report 09/08/2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welch HG, Wennberg DE, Welch WP. The use of Medicare home health care services. New Engl J Med. 1996;335:324–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608013350506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenney GM, Dubay LC. Explaining area variation in the use of Medicare home health services. Med Care. 1992;30:43–57. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes SL, Ulasevich A, Weaver FM, et al. Impact of home care on hospital days: a meta analysis. Health Serv Res. 1997;32:415–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anttila SK, Huhtala HS, Pekurinen MJ, Pitkajarvi TK. Cost-effectiveness of an innovative four-year post-discharge programme for elderly patients—prospective follow-up of hospital and nursing home use in project elderly and randomized controls. Scand J Public Health. 2000;28:41–6. doi: 10.1177/140349480002800108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higginson I. Palliative care services in the community: what do family doctors want? J Palliat Care. 1999;15:21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nolan TW. Understanding medical systems. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:293–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-4-199802150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine M, Gent M, Hirsh J, et al. A comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin administered primarily at home with unfractionated heparin administered in the hospital for proximal deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:677–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mamon J, Steinwachs DM, Fahey M, Bone LR, Oktay J, Klein L. Impact of hospital discharge planning on meeting patient needs after returning home. Health Serv Res. 1992;2:155–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders. JAMA. 1999;281:613–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:999–1006. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1190–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boling PA. The value of targeted case management during transitional care. JAMA. 1999;281:656–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuck AE, Aronow HU, Steiner A, et al. A trial of annual in-home comprehensive geriatric assessments for elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1184–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams FG, Warrick LH, Christianson JB, Netting FE. Critical factors for successful hospital-based case management. Health Care Manage Rev. 1993;18:63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hibberd PA. The primary/secondary interface. Cross-boundry teamwork—missing link for seamless care? J Clin Nurs. 1998;7:274–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1998.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]