Abstract

CONTEXT

Drug-abusing patients utilize extensive amounts of health services resources, yet the acute medical hospitalization has typically not been used effectively to engage patients in substance abuse treatment.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the effect of an integrated substance abuse/acute medical care day hospital (DH) intervention.

DESIGN AND SETTING

Prospective, consecutive chart review of patients referred to a day hospital program from the medicine service at an urban tertiary care teaching hospital. From the referral cohort, a comparison group receiving usual care was identified.

PARTICIPANTS

One hundred twenty adult medicine inpatients with active substance abuse and self-identified motivation to enter treatment.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Outpatient substance abuse treatment entry and post-intervention health services utilization.

RESULTS

Following DH treatment, 50.6% entered further outpatient substance abuse treatment (vs 2.4% comparison patients; P < .001). There was a significant increase in ambulatory medical visits for DH patients (pre–6 month 0.49 vs post–6 month 3.46; P < .001), greater than the change noted for comparison patients. However, there was no difference noted in pre-post hospitalization or emergency department utilization following the DH intervention.

CONCLUSIONS

A DH program for substance abusing hospitalized medicine patients that introduces substance abuse treatment during treatment for an acute medical illness does appear to improve outpatient substance abuse treatment entry and ambulatory care utilization after hospital discharge.

Keywords: substance abuse treatment, health services utilization, integrated care

Acute care hospitalizations for persons with substance abuse disorders represent a substantial burden on the health care system. The prevalence of active substance-abusing patients in inpatient services has been identified at between 11.8% and 30%,1–3 and drug users were found to be 2.3 times as likely to use an emergency room and 6.7 times as likely to be hospitalized as drug nonusers.4 Although the general hospital represents a significant capture point for these patients, few actually enter substance abuse treatment as a result of a health professional referral. According to the 1996 Treatment Episode Data Set, only 6.9% of all clients and 4.9% of heroin-addicted clients admitted to publicly funded substance abuse programs were referred by health professionals.5

Despite the paucity of referrals, there are a number of features within the acute presentation to the hospital that have been associated with behavior change and readiness to enter treatment. These include the acuity of the illness, perceived loss, perceived coercion, and attribution of the medical condition to substance abuse.6–12 A history of previous medical hospitalizations has also been associated with seeking substance abuse treatment.13 However, to what extent and how the hospitalization episode contributes to the decision to enter drug and alcohol treatment programs or address underlying chronic disease care is unclear.

Typical interventions within primary care and hospitalized settings have centered on brief interventions and the use of consult-liaison services with varying degrees of effectiveness.14–18 Specific transitional support for patients moving from inpatient to outpatient services has also been shown to be effective,19,20 although not specifically applied to a general hospital setting. Here patients are also transitioning from a more patient-passive, medically oriented treatment plan to a more patient-active, goal-oriented substance abuse treatment approach. Less is known about the effectiveness of integrated medical/substance abuse treatment. In an outpatient medical clinic setting, integrated substance abuse and medical care was shown in both a quasi-experimental trial and a randomized controlled trial to significantly improve abstinence and engagement in treatment among participants.21,22 Likewise, introducing primary care services into outpatient treatment settings has also been shown effective.23–25

The acute medical hospitalization represents a significant opportunity to engage patients during a vulnerable period of time, when they are likely to be receptive to lifestyle changes. It also represents an opportunity to make effective use of the time spent in the hospital between antibiotic dosing or other care interventions. The effect of introducing and incorporating cognitive/behavioral substance abuse treatment into the acute medical hospitalization episode is not known. We report findings from a prospective chart review of hospitalized medical patients participating in an integrated medical/substance abuse treatment day hospital (DH) model, assessing post-discharge outpatient treatment entry rates and 6-month health services utilization.

METHODS

The study was a prospective, consecutive chart review of medicine inpatients referred to the Johns Hopkins Day Hospital substance abuse treatment program. Two study cohorts, those admitted to the day hospital program for completion of their medical therapy, and comparably motivated patients referred to the program but not admitted due to space limitations, were identified. A chart review was conducted for both groups, assessing post-discharge outpatient substance abuse treatment entry, rehospitalizations, and use of ambulatory and emergency department services during the 6 months pre- and post-hospitalization. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to conducting this study.

Patient Population

To be considered for this study, patients had to have been referred by the admitting medicine inpatient service to the DH for evaluation and interviewed by the interventionist to assess motivation for treatment, ability to participate in the program (e.g., ambulatory, adequate stamina, cognitively intact), and medical appropriateness (e.g., requiring ongoing skilled nursing care or intravenous antibiotics). Motivation for treatment was assessed by the interventionists on the basis of 3 criteria: (1) interest in stopping drug and/or alcohol use; (2) stated willingness to make changes in their life in order to stop using; (3) willingness to enter the DH program and abide by all stated rules. Additional exclusion criteria included enrollment in a managed care organization that did not cover DH treatment services.

The interventionists assessed the patients on multiple occasions during their hospital stay and made determinations of eligibility on the basis of their most recent encounter. Standardized measures of motivation and readiness for change or of addiction severity were not used in the assessment. Similarly, aside from being admitted to the hospital for a medical complication of substance abuse and having a self-identified need for treatment and interest in stopping, no formal assessment of Diagnostic Standard Manual–Fourth Edition criteria for abuse, dependence, or harmful/risky use was determined.

A total of 179 adult medicine service inpatient referrals were screened from April 19, 1998 to January 24, 2000 with 79 DH patients and 41 non-admitted comparison patients identified. Of the 59 patients not included in this study, 17 were excluded because they were nonambulatory, 3 had insurance that did not cover DH treatment, 5 were transferred to another facility, 21 had incomplete referral or medical records, 10 were readmissions to the DH program, and 3 were nonmedical patients. No patients in either cohort were in a methadone maintenance program or were referred to a methadone maintenance program on discharge from the hospital.

Day Hospital Intervention

The First Step Day Hospital at Johns Hopkins is an 8-bed integrated treatment program for drug- and alcohol-addicted persons referred from inpatient medicine or psychiatry inpatient units. For medicine patients, the range of stay is 2 to 6 weeks, based on the need for concurrent medical therapy that cannot be provided in an ambulatory setting. Patients continue to receive their inpatient-level medical therapy (e.g., intravenous antibiotics, wound care) while receiving intensive individual and group cognitive/behavioral–based substance abuse treatment. In some instances, detoxification begun on the medical service is continued on the DH service if not completed during the acute hospitalization. Patients are also introduced to the 12-step recovery model and attend Narcotics Anonymous meetings 4 times a week. At night, the patients stay at an off-campus supervised domicillary, structured as a modified therapeutic community. The program operates 7 days a week, with all meals at the day hospital, and supervised transportation provided to and from the domicillary unit. The DH is staffed by an internist, a psychiatrist, a nurse practitioner, a nurse, a social worker, and addictions counselors. Upon completion of the program, care is transitioned to a community-based intensive outpatient (IOP) treatment program.

Usual Care

Patients receiving usual care on the medicine service at Johns Hopkins Hospital received the standard of care for their presenting condition and medical needs. This includes opiate detoxification using buprenorphine-based agonist/antagonist therapy, unless an acute pain syndrome requires opiate analgesia, which is subsequently tapered off. They also received a consult by an addictions counselor, who conducts an assessment and provides a brief intervention to encourage the patient to enter treatment. If a patient did not meet criteria for the DH, or if there was no available space in the DH, they were referred upon discharge for IOP treatment at the Johns Hopkins Program for Alcoholism and Other Drug Dependencies (PAODD) located 2 blocks from the hospital.

Data Collection

The following data were collected from a review of the electronic medical records of each patient from their initial hospitalization episode: age, race, gender, admitting diagnosis, presence of chronic illness or condition, insurance status, drugs or alcohol being abused on admission, HIV status, current medications, and length of stay. Electronic medical record review of claims and care documentation was also used to assess 6-month pre- and post-hospital emergency department and ambulatory care and substance abuse treatment utilization within the Johns Hopkins system.

Health Services Utilization

Only those health care episodes within the Johns Hopkins Health System were assessed. This included care at the PAODD substance abuse outpatient treatment unit, all Hopkins outpatient medicine clinics and emergency department visits, and inpatient admissions to Johns Hopkins Hospital. Care received at the HIV specialty clinics was coded separately but included with the ambulatory clinics. Follow-up appointments not in a medicine or HIV clinic (e.g., cast clinic, physical therapy, wound care clinic) were coded as “other” and were not included in this analysis. Initial presentations to either the emergency department or ambulatory center that resulted in the hospital admission were not coded as additional utilizations, since they represent contiguous treatment for the same presenting condition. Readmissions to the hospital or after-hours evaluations in the emergency department for DH patients were considered in 2 ways: (1) as part of the contiguous acute medical treatment and not coded as discrete events; and (2) as discrete health utilization events and included as part of the post-hospitalization analysis. Successful engagement in outpatient substance abuse treatment was defined for this study to be 3 outpatient visits within the first month post-hospital or post-DH discharge. This was done to minimize the potential over-reporting that could occur from clients presenting only on their first day of transition to IOP and not returning. Six-month health services utilization was calculated from the time the patient left the day hospital, or if they did not enter the day hospital, after they left the general hospital.

Data Analysis

Substance abuse treatment entry and health services utilization were considered dependent variables for the purposes of this analysis, with day hospital treatment, patient demographics, and presenting diagnoses the independent variables. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA (Intercooled Stata 6; Stata Corp., College Station, Tex) software. Proportions analyses comparing health services utilization (inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, IOP), and treatment entry pre- and post-hospitalization were conducted using Fischer's exact test. Because the distribution of health care episodes was not normally distributed for any care site, the Sign test was used within groups to test the null hypothesis that the median of differences between pre- and post-utilization variables was zero. For comparisons of distributions between groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. X2 analyses were conducted on discrete demographic variables using a 2-sided α of 0.05 to determine significance.

RESULTS

Demographics

As shown in Table 1, the majority of individuals in both the intervention and comparison groups were male and African American; the mean age of the DH group was 3 years older than the comparison group (42.4 years vs 39.5 years; P = .03). The vast majority of individuals in both groups were injection drug users (81.0% vs 92.7%) with most being polysubstance users. Only 5.1% of the intervention group and 2.4% of the comparison group had received any identified substance abuse outpatient treatment in the 6 months preceding this admission. The most common primary diagnosis in both groups was endocarditis (confirmed or rule-out) followed by deep-tissue abscesses. However, those patients in the usual care/comparison group had more diagnoses associated with shorter lengths of stay (rule-out endocarditis, fever of unknown origin, and cellulitis) than did the day hospital group, which had more longer-term treatment diagnoses (confirmed endocarditis, osteomyelitis). Almost 40% in both groups were HIV positive, and similar proportions had at least 1 chronic medical condition. The majority of individuals in both groups did not have health insurance. The mean hospital inpatient length of stay was 10.0 days (SD 5.8; range, 2 to 27 days) for the day hospital/concurrent treatment group and 9.4 days (SD 11.5; range, 1 to 48 days) for the usual care/comparison group. Those persons entering the day hospital/concurrent treatment program stayed for a mean of 15.8 days (SD 10.7; range, 0 to 40 days) in that program. The mean length of stay for combined inpatient/day hospital care was 25.6 days (SD 13.6; range, 2 to 57 days).

Table 1.

Demographics: Integrated Medical/Substance Abuse Day Hospital Cohort and Controls

| Demographics | Day Hospital (n = 79) | Control (n = 41) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 46 (58.2) | 21 (51.2) | .46 |

| Race (AA), n (%) | 73 (92.4) | 36 (87.8) | .41 |

| Age, y (%) | |||

| 18–35 | 10 (13.7) | 10 (25.0) | .13 |

| 36–45 | 37 (50.6) | 23 (57.5) | .48 |

| 46–55 | 25 (34.3) | 7 (17.5) | .06 |

| >55 | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | .45 |

| Drug use, n (%) | |||

| IDU | 64 (81.0) | 38 (92.7) | .09 |

| Heroin | 54 (68.4) | 32 (78.1) | .26 |

| Cocaine | 49 (62.0) | 26 (63.4) | .88 |

| Alcohol | 36 (45.6) | 23 (56.1) | .28 |

| HIV status (+), n (%) | 30 (38.0) | 16 (39.0) | .92 |

| Primary hospital dx, n (%) | |||

| Endocarditis | 29 (36.7) | 14 (34.1) | .78 |

| Cellulitis | 6 (7.6) | 6 (14.6) | .23 |

| Osteomyelitis | 13 (16.5) | 1 (2.4) | .02 |

| Abscess | 18 (22.8) | 10 (24.4) | .84 |

| HIV-related | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.4) | .66 |

| Other | 12 (15.2) | 9 (22.0) | .35 |

| Insurance status | |||

| None | 38 (76.0) | 31 (81.6) | .48 |

| Medicaid (HMO and FFS) | 6 (12.0) | 3 (7.9) | .49 |

| Medicare | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | .36 |

| Private insurance | 4 (8.0) | 3 (7.0) | .85 |

| Comorbid medical conditions, n (%) | 29 (36.7) | 17 (41.5) | .61 |

| Hypertension | 15 (19.0) | 9 (22.0) | .70 |

| Diabetes | 5 (6.3) | 2 (4.9) | .76 |

| Heart disease | 3 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | .21 |

| Hepatitis B/C | 48 (60.8) | 30 (73.1) | .23 |

AA, African American; IDU, intravenous drug use; FFS, fee-for-service.

Outpatient Treatment Entry Following the Acute Hospitalization

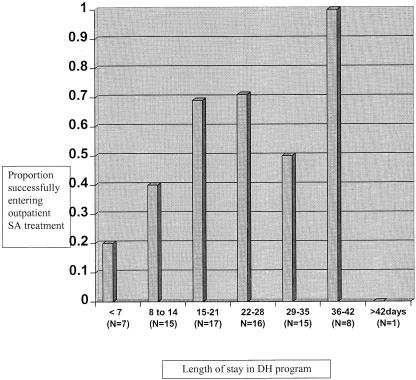

Of the 120 DH intervention and usual care patients identified during their hospitalization as motivated to enter treatment, 41 persons actually entered IOP treatment upon discharge. Of those 41 IOP patients, 40/79 (50.6%) were from the day hospital/concurrent treatment cohort and 1/40 (2.4%) was from the usual care group. As shown in Table 2, there were no demographic differences in age, race, gender, primary diagnoses, or comorbid conditions between those persons entering and not entering outpatient treatment from the day hospital program. Clients enrolled in the day hospital/concurrent treatment program for longer periods of time had higher outpatient treatment entry rates than did those persons enrolled for fewer than 2 weeks (68.1% vs 28.6%; P < .001); this difference remained significant after excluding those patients who left the program within the first 4 days of their admission (i.e., against medical advice discharges; P = .027) (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Comparison of Outpatient Substance Abuse Treatment Entry and Treatment Nonentry Among Day Hospital Patients

| Demographics | Outpatient Treatment Entry (n = 40) | Outpatient Treatment Nonentry (n = 39) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 21 (52.5) | 25 (64.1) | .30 |

| Race (AA), n (%) | 37 (92.5) | 36 (92.3) | .97 |

| Age, y (%) | |||

| 18–35 | 7 (17.5) | 3 (7.7) | .19 |

| 36–45 | 17 (42.5) | 20 (51.3) | .43 |

| 46–55 | 14 (35.0) | 11 (28.2) | .52 |

| >55 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.6) | .31 |

| Drug use, n (%) | |||

| IDU | 33 (82.5) | 31 (79.5) | .74 |

| Heroin | 27 (67.5) | 27 (69.2) | .87 |

| Cocaine | 23 (57.5) | 26 (66.6) | .41 |

| Alcohol | 18 (45.0) | 18 (46.2) | .92 |

| HIV status (+), n (%) | 11 (27.5) | 19 (47.5) | .07 |

| Primary hospital dx, n (%) | |||

| Endocarditis/FUO | 15 (37.5) | 14 (.35.9) | .88 |

| Cellulitis | 3 (7.5) | 3 (7.7) | .97 |

| Osteomyelitis | 5 (12.5) | 8 (20.5) | .34 |

| Abscess | 8 (20.0) | 10 (25.6) | .55 |

| HIV-related | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | .32 |

| Other | 8 (.20.0) | 4 (10.3) | .23 |

| Insurance status, n (%) | |||

| None | 20 (50.0) | 18 (46.1) | .73 |

| Medicaid (HMO and FFS) | 1 (2.5) | 5 (12.8) | .08 |

| Medicare | 0 (0) | 1 (2.6) | .31 |

| Private insurance | 1 (2.5) | 3 (7.7) | .29 |

| Comorbid medical conditions, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 9 (22.5) | 6 (15.4) | .42 |

| Diabetes | 2 (5.0) | 3 (7.7) | .62 |

| Heart disease | 0 (0) | 3 (7.7) | .07 |

| Hepatitis B/C | 22 (55.0) | 26 (66.7) | .29 |

AA, African American; IDU, intravenous drug use; FUO, fever of unknown origin; FFS, fee-for-service.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of length of stay in day hospital program with subsequent outpatient substance abuse treatment entry.

Health Services Utilization

As shown in Table 3, there was no significant difference in the average number of episodes of care per person for emergency department or hospital admissions in either the 6 months pre-post analysis or in comparing the DH to the usual care group. Both cohorts had more ambulatory episodes of care per person post-hospitalization, reaching significance for the day hospital/concurrent treatment group (0.49, 3.46 episodes of care per person; P < .001). As with the average number of episodes per person, there was no difference in the proportion of individuals in either group utilizing inpatient care pre- and post-hospitalization. A lower proportion of individuals from the day hospital/concurrent treatment cohort utilized emergency department services post-intervention while higher proportions from both groups utilized ambulatory services post hospitalization, with a greater difference noted among the day hospital cohort.

Table 3.

Health Services Utilization Patterns

| Usual Care | Day Hospital | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit Type | Pre, n (%) | Post, n (%) | P Value | Pre, n (%) | Post, n (%) | P Value |

| Emergency department | 1.51 (68.2) | 1.43 (57.5) | .12 (.17) | 1.67 (60.8) | 1.60 (49.4) | 1.0 (.20) |

| Hospital admission | 0.46 (31.7) | 0.37 (29.3) | 1.0 (1.0) | 0.42 (31.6) | 0.56 (35.4) | .22 (.74) |

| Ambulatory care visit | 0 (0) | 0.29 (12.2) | .06 (.05) | 0.48 (19.0) | 3.46 (52.6) | <.001 (<.001) |

Ordinal values represent mean visits/patient; P values were determined by comparisons within groups pre- and post-hospitalization using the Sign test. Percentile values in parentheses represent percent of patients making at least 1 visit to that site; P values determined by comparison of proportions using Fischer exact test.

When emergency department visits and re-hospitalizations occurring during the DH intervention were analyzed as discrete episodes, 11 additional inpatient admissions and 6 additional emergency department episodes were identified among the 79 patients. The inclusion of the 11 additional inpatient admissions resulted in a significant increase in the average number of post-hospitalization inpatient episodes of for the DH cohort (0.42 to 0.70 episodes of care per person, P = .02). The inclusion of the 6 additional emergency department visits did not significantly alter the pre-post analysis (1.67, 1.66, P = 1.0).

Subgroup analyses comparing utilization rates among those persons entering outpatient treatment and among those persons staying in outpatient treatment for more than 5 months also identified no significant difference in emergency department or hospitalization rates. The difference in pre-, post-ambulatory rates was more robust for those persons entering treatment (0.30 to 4.75 episodes of care per person, P < .001) and for those in outpatient treatment for more than 5 months (0.14 to 7.71 episodes of care per person; P = .002) compared with those not entering treatment (0.32 to 1.16 episodes of care per person, P = .014).

A breakdown of the post-hospitalization ambulatory services received by both groups was notable for the preponderance of HIV-related care received. Of the 3.46 ambulatory care episodes per person noted in the DH/concurrent treatment group, 2.1 of those episodes were at HIV-specific clinics. HIV-positive patients in this group had an average of 5.6 HIV-specific ambulatory care episodes per person during the 6-month study period. Among the usual care group, of the 0.29 ambulatory care episodes noted for the group, 0.20 ambulatory care episodes per person were at HIV-specific clinics. However, in contrast to the DH/concurrent treatment group, HIV-positive usual-care patients received only 0.5 HIV-specific ambulatory care episodes per person in the 6 months post–hospital discharge.

DISCUSSION

These findings suggest that substance abuse treatment can be effectively introduced during an acute medical hospitalization for motivated patients receiving prolonged medical therapy. The benefits of this concurrently administered treatment are noted in high rates of both subsequent participation in outpatient drug treatment and in ambulatory care utilization. Previous studies examining the role of consult-liaison services and brief interventions in the care of medical patients have noted enhanced outpatient substance abuse treatment entry, reduced alcohol intake, tobacco cessation, and cost-effectiveness. However, while these approaches are appropriate in settings in which the time available to intervene with a patient is limited, less is known about alternative approaches when the patient is available for longer periods, is more ill, and generally has fewer resources to access care and effect change. There is also a growing body of literature demonstrating the benefits of integrating and coordinating medical and mental health services with substance abuse treatment, with positive outcomes noted in treatment retention,21,22 primary care utilization,23,24 and mental health care.26,27 However, these studies have focused on outpatient populations and have not looked at interventions that integrate substance abuse treatment during the acute medical hospitalization. While there are many limitations to the methodologies used in this study, the findings nevertheless support the viability of this model and potential replicability to other centers.

Urban health centers and hospitals are commonly the safety-net providers for poor inner-city residents, many of whom have co-occurring substance abuse problems. Many of these patients do not have health insurance, similar to the sample reported in this paper and consistent with the increasing amount of uncompensated care provided by academic health centers. The costs to health systems of these patients, both in lengthy acute care hospitalizations for complications from their drug use and in the medical consequences of deferred primary care for chronic medical conditions, represent a substantial financial burden. It follows that taking a more holistic and ecologic approach to the care of these patients will benefit both the patient and the hospital. The model described here uses an integrated team model to address underlying mental health and addiction issues that often are deferred in the context of an acute medical illness. Similarly, the use of a community-based domicillary serves not only to open up hospital beds and reduce lengths of stay but also to address the homelessness and personal chaos facing many of these patients. Additionally, it connects them to viable network community resources essential to sustaining recovery. Integrating hospital-based care with community resources is an effective model for urban health care for special-needs populations.

While ambulatory care use post-hospitalization increased for both the day hospital cohort and the comparison group, the increases were more robust in the day hospital group and especially among those individuals who stayed in outpatient treatment longer. It is important to note that while these health utilization indices serve as a weak surrogate for actual patient outcomes, they do suggest an important role within drug treatment and during the acute hospitalization for establishing and legitimizing the primary care relationship. They also argue for the importance of the generalist in actively coordinating the care needs of these patients and facilitating substance abuse treatment retention upon hospital discharge. In a study by Samet and O'Connor, most patients in whom alcohol abuse was detected in primary care were either actively addressing their substance abuse or were in recovery.28 The primary care provider needs to be able to reinforce his or her patients' outpatient treatment efforts and ensure that their care plans are consistent with treatment objectives.

The use of the comparison group in this study needs to be qualified on several levels. Although similar demographically, the comparison group typically had diagnoses associated with shorter lengths of stay and can be presumed to be less ill than the day hospital cohort. Without standardized measures of addiction severity and motivation or readiness for change, it is difficult to make any true comparisons or to consider this group to be a control population. However, describing utilization outcomes associated with this group does provide some indication of the effectiveness of usual care, particularly in terms of outpatient treatment entry and use of ambulatory care services. With almost 40% of both cohorts HIV positive and with a high burden of chronic medical conditions, the differences noted in ambulatory care utilization are important if, however, only suggestive of an effective impact.

The increase in hospitalizations noted post-intervention in the day hospital group likely reflects the prolonged acuity of need and ill health of this cohort. Alternately, the high level of hospitalization and emergency department service use may reflect a pattern of health care–seeking behavior that is more predictive of subsequent utilization, as has been demonstrated in other studies.29 While these findings differ somewhat from those of Laine et al., who noted decreased hospitalizations associated with subsequent ambulatory and drug abuse care, they do suggest a causal link between hospital-based interventions and subsequent increased outpatient utilization.30 We suspect that more-focused interventions specifically aimed at emergency department utilization using case management31 or other approaches may be needed to achieve comparable utilization outcomes within this site of care. More research in this area is needed.

As previously noted, there are several limitations to this study that need to be considered when interpreting these findings. First, the study cohorts are relatively small, and the sample size may not provide enough power to draw additional conclusions. Second, we have relied on chart review and passive data tracking to assess client characteristics and health services utilizations. This poses several noteworthy biases, including missing and incomplete data on patient demographic and substance use characteristics that limits broader generalizations of the study population. There is also likely an underreporting bias of health services utilization pre- and post-hospitalization, since some clients may have sought care outside of the Hopkins health system. One would suspect that the underreporting bias would be larger in the population not engaged in outpatient substance abuse treatment, which is more concentrated in the comparison group. Finally, as stated earlier, we did not have standardized assessments of patient motivation or addiction severity that would have allowed for more meaningful comparisons of the intervention and comparison groups and characterization of the study cohort. Future prospective studies will address this issue.

It is also unclear from our data what elements within the integrated intervention were most effective and whether the outcomes are solely time-in-treatment dependent or associated with specific client-based or intervention-based variables. Similarly, it is unclear whether these results can be replicated in more rigorous, prospective trials. Finally, this study was not designed to assess treatment retention, since we are unable to determine how many clients transferred their care to other sites as they enrolled in more structured or housing-linked treatment programs as opposed to dropping out of treatment for reasons independent of the intervention.

In summary, these findings suggest a meaningful opportunity to engage patients in substance abuse treatment during an acute medical hospitalization. This and the enhanced subsequent ambulatory care utilization noted represent substantive opportunities for generalist physicians to take a proactive role in the care of patients with substance abuse disorders.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by the Lattman Family Foundation and by Public Health Service Grant NIDA K23 DA 13988-01.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stein MD, Wilkinson J, Berglas N, O'Sullivan P. Prevalence and detection of illicit drug disorders among hospitalized patients. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1996;3:463–71. doi: 10.3109/00952999609001672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown RL, Leonard T, Saunders LA, Papasouliotis O. The prevalence and detection of substance use disorders among inpatients ages 18 to 49: an opportunity for prevention. Prev Med. 1998;27:101–10. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore RD, Bone LR, Geller G, Mamon JA, Stokes EJ, Levine DM. Prevalence, detection and treatment of alcoholism in hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1989;261:403–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein MD, O'Sullivan PS, Ellis P, Perrin H, Wartenburg A. Utilization of medical services by drug abusers in detoxification. J Subst Abuse. 1993;5:187–93. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90062-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.1996 Treatment Episode Data Set. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Available at: http://www.samsha.gov//oas/teds/99teds/99teds.pdf. Accessed August, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baile WF, Bigelow GE, Gottlieb SH, Stitzer ML, Sacktor JD. Rapid resumption of cigarette smoking following myocardial infarction: inverse relation to MI severity. Addict Behav. 1982;7:373–80. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blume AW, Schmaling KB. Loss and readiness to change substance abuse. Addict Behav. 1996;21:527–30. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polcin DL, Weisner C. Factors associated with coercion in entering treatment for alcohol problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54:63–8. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wild TC, Newton-Taylor B, Alletto R. Perceived coercion among clients entering substance abuse treatment: structural and psychological determinants. Addict Behav. 1998;23:81–95. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hser YI, Maglione M, Polinsky ML, Anglin MD. Predicting drug treatment entry among treatment-seeking individuals. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1998;15:213–20. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisner C. The role of alcohol-related problematic events in treatment entry. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1990;26:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(90)90116-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reich JW, Gutierres SE. Life event and treatment attributions in drug abuse and rehabilitation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1987;13:73–9. doi: 10.3109/00952998709001501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strathdee SA, Celentano DD, Shah N, et al. Needle-exchange attendance and health care utilization promote entry into detoxification. J Urban Health. 1999;76:448–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02351502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller MG, Diamond DL, Jordan ML, Walters MC. The role of a substance abuse consultation team in a trauma center. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:267–71. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burton RW, Lyons JS, Devens M, Larson DB. Psychiatric consultations for psychoactive substance disorders in the general hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1991;13:83–7. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(91)90018-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn CW, Ries R. Linking substance abuse service with general medical care: integrated, brief interventions with hospitalized patients. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23:1–13. doi: 10.3109/00952999709001684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aszalos R, McDuff DR, Weintraub E, Montoya I, Schwartz R. Engaging hospitalized heroin-dependent patients into substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1997;14:155–62. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chick J, Lloyd G, Crombie E. Counseling problem drinkers in medical wards: a controlled study. BMJ. 1985;290:965–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6473.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conti DJ, Verinis JS. The effect of pre-bed care on alcoholic patients' behavior during inpatient treatment. Int J Addict. 1989;24:707–14. doi: 10.3109/10826088909047307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson M, Foreman L, Tomlin W, Bright V. Facilitating problem drinking clients' transition from inpatient to outpatient care. Health Social Work. 1994;19:23–8. doi: 10.1093/hsw/19.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willenbring ML, Olson DH, Bielinski J. Integrated outpatient treatment for medically ill alcoholic men: results from a quasi-experimental study. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:337–43. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willenbring ML, Olson DH. A randomized trial of integrated outpatient treatment for medically ill alcoholic men. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1946–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.16.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umbrict-Schneiter A, Ginn DH, Pabst KM, Bigelow GE. Providing medical care in methadone clinic patients: Referral vs. on-site care. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:207–10. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selwyn PA, Budner NW, Wasserman WC, Arno PS. Utilization of on-site primary care services by HIV-seropositive and seronegative drug users in a methadone maintenance program. Public Health Rep. 1993;108:492–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pickens RW, Fletcher BW. Overview of Treatment Issues. Improving Drug treatment. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; DHHS Publication no. (ADM) 91–1754:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McClellan AT, Grissom GR, Brill P, Durell J, Metzger DS, O'Brien CP. The effects of psychosocial service in substance abuse treatment. JAMA. 1993;269:1953–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D'Aunno TA, Price RH. Organizational adaptation to changing environments: community mental health and drug abuse services. Am Behav Sci. 1985;28:669–83. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samet JH, O'Connor PG. Alcohol abusers in primary care: readiness to change behavior. Am J Med. 1998;105:302–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neimcryk SJ, Bedros A, Marconi KM, O'Neill JF. Consistency in maintaining contact with HIV-related service providers: an analysis of the AIDS Cost and Services Utilization Study (ACSUS) J Community Health. 1998;23:137–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1018713524788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laine C, Hauck WW, Gourevitch MN, Rothman J, Cohen A, Turner BJ. Regular outpatient medical and drug abuse care and subsequent hospitalization of persons who use illicit drugs. JAMA. 2001;285:2355–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okin RL, Boccellari A, Azocar F, et al. The effects of clinical case management in hospital service use among ED frequent users. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:603–8. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2000.9292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]