Abstract

CONTEXT

Communication of bad news to patients or families is a difficult task that requires skill and sensitivity. Little is known about doctors' formative experiences in giving bad news, what guidance they receive, or what lessons they learn in the process.

OBJECTIVE

To learn the circumstances in which medical residents first delivered bad news to patients or families, the nature of their experience, and their opinions about how best to develop the needed skills.

DESIGN

Confidential mailed survey.

SETTING AND SUBJECTS

All medicine house officers at 2 urban, university-based residency programs in Boston.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Details of medical residents' first clearly remembered experiences of giving bad news to a patient or family member; year in training; familiarity with the patient; information about any planning prior to, observation of, or discussion after their first experience; and the usefulness of such discussions. We also asked general questions about delivering bad news, such as how often this was done, as well as asking for opinions about actual and desired training.

RESULTS

One hundred twenty-nine of two hundred thirteen surveys (61%) were returned. Most (73%) trainees first delivered bad news while a medical student or intern. For this first experience, most (61%) knew the patient for just hours or days. Only 59% engaged in any planning for the encounter. An attending physician was present in 6 (5%) instances, and a more-senior trainee in 14 (11%) others. Sixty-five percent of subjects debriefed with at least 1 other person after the encounter, frequently with a lesser-trained physician or a member of their own family. Debriefing focused on the reaction of those who were given the bad news and the reaction of the trainee. When there were discussions with more-senior physicians, before or after the encounter, these were judged to be helpful approximately 80% of the time. Most subjects had given bad news between 5 and 20 times, yet 10% had never been observed doing so. Only 81 of 128 (63%) had ever observed an attending delivering bad news, but those who did found it helpful 96% of the time. On 7-point scales, subjects rated the importance of skills in delivering bad news highly, (mean 6.8), believed such skill can be improved (mean 6.6), and thought that more guidance should be offered to them during such activity (mean 5.8).

CONCLUSION

Medical students and residents frequently deliver bad news to patients and families. This responsibility begins early in training. In spite of their inexperience, many do not appear to receive adequate guidance or support during their earliest formative experiences.

Keywords: doctor-patient communication, graduate medical education, survey research

Perhaps no physician-patient encounter is more stressful than one in which bad news is given. Doctors in training cite their own anxiety, lack of supervisory support, and time constraints as barriers to giving bad news, while testimonials from patients, family members, and students remind us of the consequences of poor communication and how this negatively affects others' perception of our humanity.1–4 Numerous reviews and guidelines offer advice or serve as resources for those interested in personal improvement or in teaching others.5–16 In addition, medical school courses and programs for post-graduate training have been developed, some of which have received positive evaluations.17–26 However, the effectiveness of such curricula across undergraduate and graduate medical education is unknown. The scant information collected from medical students27,28 and house officers28–30 suggests that they perceive themselves to be inadequately trained in delivery of bad news, and the one study that measured this ability31 confirms this assessment.

Since the time of Flexner, and even earlier,32 it has been a tenet of medical education that one must “learn by doing,” because classroom education—although important—is insufficient. This approach carries with it the obligation to supervise trainees, in order to guide their learning while ensuring good care for patients. It is our view that delivering bad news is a skill that must be learned in this way. It is delicate, challenging, and inarguably of great importance to the practice of medicine.

We were interested in medical residents' first clearly remembered experiences of giving bad news because we thought it would open a window on the way that they are supervised and how they learn. To this end, we examined the circumstances in which medical residents first clearly remember breaking bad news, as well as their views about how best to teach and learn the needed skills. Our goal was to identify opportunities to improve education and patient care through more detailed knowledge of the context and circumstances of these doctors' early experiences.

METHODS

Survey Administration

We surveyed all internal medicine residents, (PGY 1, 2, and 3) in 2 urban university-affiliated programs, Boston University and Tufts New England Medical Center. For the study cohorts, program directors provided a list of medical schools from which their residents graduated. We cross-referenced these lists to determine the total number of unique schools represented. We sent out 2 sequential mailings of the confidential survey in the spring of 1996 to 213 residents in the 2 training programs. They had graduated from 70 different medical schools (52 in the United States, 1 in Canada, and 17 abroad) and rotated through 7 different affiliated hospitals in the greater Boston area. No identifiers were on the survey itself, so once separated from the envelope, responses could not be traced to individuals.

Survey Content

We developed the survey instrument after a review of relevant literature and after conducting a focus group of general internal medicine fellows during which they discussed their initial experiences delivering bad news. We piloted the survey among the same fellows to assess the clarity and pertinence of the questions. The final instrument consisted of 42 questions. We defined bad news as “news that will change a patient's outlook for the future in a very negative way. Such bad news can be about a severe illness, prospect of death, or increasing levels of limitation.” We asked respondents about objective and subjective aspects of their “first clearly remembered experience delivering bad news to a patient or patient's family.” Our 4 initial questions queried type of bad news delivered, stage of training, type of service, and length of time they knew the patient. If respondents checked off “can't remember” or left blank more than 2 of these first 4 questions, the survey was excluded from analysis and classified as “not clearly remembered.” We then asked for further details about the incident, such as any planning prior to or debriefing that occurred following the event, and their reaction to the encounter.

We also solicited general information related to delivering bad news: how often it occurred, types and sources of training and support, as well as opinions about what sorts of training were most helpful. Subjective questions were answered using 7-point Likert scales.

Structured inquiry into understudied processes can often miss important information. Therefore, we included several opportunities for open-ended responses in which subjects could describe events, emotions, and reactions in detail. Examples include: “Can you recall any concerns or feelings you had prior to seeing the patient/family? If so what?” and, in relation to the first remembered experience delivering bad news, “Do you recognize an effect that this experience has had on you? If yes, what?” The final question asked was, “Please comment on anything you would like to express or feel we have left out of this survey.”

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated using the SPSS statistical package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill). After analyzing responses to questions with Likert scales, we reviewed the responses to the open-ended questions looking for corresponding themes. We did not do a formal qualitative analysis, but selected representative quotations within these themes that reveal our respondents' experiences in a way that Likert scales cannot. No information was collected on nonresponders.

Study Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions. Informed consent included permission from the respondents to quote their answers to open ended questions.

RESULTS

We received 129 of 213 questionnaires (61% response rate). One survey reported no experience and otherwise was left uncompleted, leaving 128 for further analysis, all meeting our criteria for “clearly remembered.” Respondents had a mean age of 29 (range 24 to 43). Forty-eight percent were women.

Settings and Circumstances

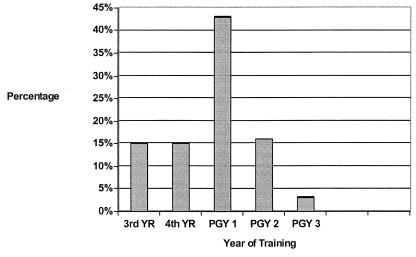

Figure 1 shows the year of training in which respondents had their first clearly remembered experience giving bad news. Thirty-eight (29%) of respondents' first experiences occurred during medical school; of the remainder, 56 (64%) occurred during internship.

Figure 1.

Stage of training when first experience giving bad news to a patient or family member occurred (N = 128).

Table 1 shows the type of bad news communicated and the setting in which it occurred. As could be anticipated, the majority of instances were discussions about grave diagnoses or deaths on inpatient medicine rotations.

Table 1.

Characterization of Type of Bad News Discussed with Patients and Their Families and Service Rotation in Which This Occurred (N = 128)

| Type | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Type of bad news | |

| Fatal diagnosis | 52 (41) |

| Serious diagnosis | 33 (26) |

| Death | 33 (26) |

| Failure of treatment | 5 (4) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Don't know/can't remember | 4 (3) |

| Service type | |

| General medical ward | 57 (45) |

| Intensive care unit | 26 (20) |

| Subspecialty medicine ward | 24 (19) |

| Surgical rotations (all types) | 9 (7) |

| Emergency room | 4 (3) |

| House officer's own continuity clinic | 1 (1) |

| Other | 5 (4) |

| Can't remember/not indicated | 2 (2) |

Residents were asked to identify the individual who exerted the greatest influence in deciding that they would be the person to deliver the bad news. Of the 121 who responded to this question, thirty-two percent of residents (n = 39) identified others: a more-senior trainee (n = 20), attending (n = 7), less-senior trainee (n = 6), nurse (n = 3), other (n = 3). The remainder (n = 82) offered to do so. Table 2 gives the reasons that they stepped forward. Approximately three fourths did so because they thought that they knew the patient best or were the most suitable person available at the time. Twenty-nine percent said that they were the most suitable one willing, which indicates that a substantial number were chosen by default. Only 10% felt that they would do a better job than others.

Table 2.

Reasons that Residents Chose to Be the One to Deliver Bad News (N = 82)

| Reason | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Knew patient best among caregivers | 62 (76)* |

| Most suitable one available | 57 (70) |

| Most suitable one willing | 24 (29) |

| Desire to gain experience | 13 (16) |

| Felt would do a better job than others | 8 (10) |

| To demonstrate to a more-junior trainee | 2 (2) |

Percents add to more than 100 because multiple answers could be given.

Among the respondents as a whole, 61% had known the patient or family for less than a week; 20% had known the patient for hours (range <1 to 16), and 41% had known the patient for days (range 1 to 6). Only 3 had a relationship of a month or more. When asked how prepared they felt to give the bad news, the mean score was 4.3 ±1.2 on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = totally unprepared, 4 = ready but uncomfortable, 7 = fully prepared).

Process

As shown in Table 3, prediscussion planning and debriefing after the encounter occurred about twice as often as direct observation, which took place about a third of the time. Attendings and more-senior trainees predominated in planning and debriefing, but were in an overall minority during observation. An attending was present in only 6 instances (5%).

Table 3.

Distribution of Individuals (Discussants) that Planned, Observed, or Debriefed with the Trainees (N = 128 trainees)

| Discussants | Planning,*n (%) | Observation, n (%) | Debriefing,*n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attending or more senior trainee | 73 (57) | 20 (16) | 78 (61) |

| Other professional† | 25 (20) | 17 (13) | 26 (20) |

| Trainee at or below same level | 22 (17) | 12 (9) | 53 (41) |

| Own family | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 41 (31) |

| Total with any discussant | 75 (59) | 40 (31) | 83 (65) |

Percents add to more than 100 because multiple answers could be given

Nurse, clergy, social worker, or other professional.

It is notable that discussion with family and more-junior physicians was much more frequent in debriefing than in the other activities. During debriefing, the most common topics were the patient's and/or family's reaction (52%), followed by the participant's own feelings (48%) and the lessons to be learned (32%).

Eighty percent of all planning discussions were reported to be somewhat or very helpful (82% of those with more-senior trainees and 72% of those with attendings). The utility of after-the-fact discussions were judged to be somewhat or very helpful to the participants 78% of the time (information about observation follows).

Experience and Opinions at the Time of the Survey

At the time of the survey, 98% of respondents had both observed others giving bad news and had given it themselves, usually between 5 and 20 times for each. However, 10% had never been observed and two thirds had been observed 4 times or less. They felt slightly more than “somewhat prepared' to deliver bad news (Table 4). Trainees believed that skill in doing so is highly important and felt strongly that it can be learned. They placed great importance on training and believed that more guidance should be offered.

Table 4.

Attitudes about Delivering Bad News (N = 128)

| Attitude | Mean Score (±S.D) |

|---|---|

| Estimate of current skill* | 5.3 (1.1) |

| Importance of having skill† | 6.8 (0.5) |

| Possibility of increasing skill‡ | 6.6 (0.7) |

| Importance of having training† | 6.0 (1.1) |

| Need for more guidance§ | 5.8 (1.1) |

1 = very unprepared, 4 = somewhat prepared, 7 = very well prepared.

1 = not at all important, 4 = somewhat important, 7= very important.

1 = not at all, 4 = somewhat, 7 = very much.

1 = none, 4 = some, 7 = much more.

Subjects who recalled having been observed delivering bad news were asked whether they received feedback and if so how useful it was. Of the 25 subjects who reported being observed by an attending, all received feedback and only 1 person reported that it was not useful.

Observing others with more experience deliver bad news was also found to be of benefit by more than 95% of respondents. Of those who had observed an attending deliver bad news (n = 81), 70% found the experience very helpful, 26% rated it somewhat helpful. Observing more-senior trainees (n = 65) was very helpful to 60% and somewhat helpful to another 38%. The value of observation of other professionals or doctors with less experience was not rated as highly (n = 87), being very helpful to 27% and somewhat helpful to 42%.

Subgroup Analyses

The Effect of Gender

There were no significant differences between males and females with regard to the type of bad news delivered, how well the trainee believed they knew the patient, how well prepared they felt, the belief that they would perform better, how often they were accompanied by more-senior clinicians, or how often they discussed their experience with others (data not shown).

More women than men believed that they were the most suitable person available (35/60 [58%] vs 20/65 [31%]; P < .005), and there was a trend for fewer women to report that they were the most suitable one willing to give the bad news, (7/60 [12%] vs 16/65 [25%]; P = .06).

The Impact of Stage of Training

Table 5 compares responses from those who first delivered bad news as students with those who did so as house officers. Students were more likely to break bad news on the general medicine wards, were less likely to self-select to deliver bad news, believed less often that they were the most suitable person available, but felt much more often that they knew the patient best. Despite their lower level of experience and lesser degree of confidence, they did not hold planning discussions more often, nor were they accompanied by others or attendings more frequently. They reported poorer performance during the bad news encounter.

Table 5.

Effect of Stage of Training on First Experiences Delivering Bad News

| Students (N = 38) | House-officers (N = 90) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency, % | |||

| Location of giving bad news was on a general medicine ward | 63 | 37 | <.001 |

| Main influence to be the one to deliver the bad news was self | 41 | 80 | <.00001 |

| Most suitable one to deliver bad news | 29 | 51 | <.05 |

| Most often knew the patient best | 74 | 38 | <.001 |

| Had a discussion in advance of delivering the bad news | 76 | 66 | .22 |

| Accompanied by other individual | 37 | 28 | .36 |

| Accompanied by a more-senior trainee | 24 | 7 | <.05 |

| Accompanied by an attending | 5 | 4 | .84 |

| Mean Likert Scores* | |||

| Anticipated patient/family reaction | 3.8 | 4.6 | <.02 |

| How well prepared for discussion | 3.4 | 4.6 | .001 |

| How well one responded to the patient/family | 4.6 | 5.3 | <.01 |

7-Point Likert scales were used; higher means represent more positive outcomes.

Students did not differ from residents in their perceptions of the need for guidance, importance of the skills involved, ability to improve, or need for training. They also did not differ in the proportion reporting that their first experience had a lasting impact on them, or in their appraisal of various teaching methods (data not shown).

Themes from Open-ended Responses

We identified 5 recurrent themes in our review of questions with open-ended responses. We labeled these themes as follows: (1) difficult circumstances, (2) powerful emotional experiences, (3) importance of topic, (4) need for support, and (5) how to learn. We did not attempt a rigorous qualitative analysis, but we provide sample comments related to each theme in Table 6.

Table 6.

Themes Developed from Review of Open-ended Questions

| 1. Difficult circumstances |

| “There was an issue about whether or not a catheter in her pleura which was pulled caused her to exsanguinate and die. I was concerned the husband would be very angry—wanting an immediate explanation for what happened which I did not have.” |

| “It was via a telephone call late at night that I called the family. I felt it was a very poor way to have to deliver the news because I prefer face-to-face contact. I also was inexperienced.” |

| “He already knew—a nurse had accidentally leaked the news. He was bitter at the indignity of how he had found out: inadvertently, while watching a cartoon.” |

| “Not only was I telling a practical stranger and her family that she had a terminal illness with no available treatment, but also that she had to leave the hospital.” |

| “[It] helped make me aware of how complex family situations make receiving bad news … difficult and how helpful it was to have the social worker and clergy involved, not only for the event of giving bad news, but in all the events that follow[ed].” |

| “It was very clear that the attending or fellow was to give the patient the news … . The fellow told the patient — [who] did not understand…— so I had to tell [the patient] later. I was very upset that [the fellow] did not take the time to see if the patient understood what [she was] saying. I was upset with the medical staff, and felt badly for the patient and family.” |

| 2. Powerful emotional experiences |

| “It was the first time in my life I had to deliver such bad news and I was unaware of the consequences of my act. I was shocked by the family's response that I was not expecting.” |

| “The son started screaming/crying on the phone and dropped it.” |

| “I had a difficult time expressing my own feelings and remorse.” |

| “I had always pictured myself delivering this type of news (as a doctor), but it took some time to realize that I had.” |

| “I had to tell my patient that he was HIV positive, and I anticipated feeling both overwhelmed with his sadness and helpless to do much for him. I paced outside the room for at least five minutes beforehand.” |

| 3. Importance of topic |

| “I feel this particular aspect of medical education is grossly neglected by attendings. It would be important to have it stressed more.” |

| “I have been so busy this year, I barely open my mail, never mind fill out a questionnaire. I think your topic is so important; it inspired me to really sit down and think. Thank you—I had not talked about my particular experience to anyone except the team.” |

| “My first experience was awkward, but I thought a lot about the process of delivering bad news … . I talked about it some, especially to my family and a couple of attendings that I respected a lot, but this was not really encouraged. Nor did I receive formal training. As a junior resident, I have made it a point to bring interns and medical students in … . I hope I am able to provide to more-junior physicians in training what I believe I would have benefited more from earlier.” |

| 4. Need for support |

| “I think more effort [needs] to be made to recognize that the delivering of bad news is emotionally stressful and MDs should be given a forum in which to talk about their experiences. It should not be just another chore on the list of things to do.” |

| “I felt that I had to learn to deal with death and dying and discussing information with patients afterward.” |

| “[There should be] discussions of … physicians' personal feelings about our limitations and failures of treatment. |

| “It was clear to me … that although the whole surgical team knew of [the patient's] fatal diagnosis … [she] did not know because no one took the time to delicately tell her and her family …. I felt that withholding this information was a horrible thing and I developed an overwhelming feeling of guilt …. It should be the more-senior resident/attending role to tell the patient of her fatal diagnosis. But when they do not adequately do this, the burden … falls upon the caregiver that spends the most time with the person….” |

| 5. How to learn |

| “I think the best way to learn this skill is by seeing others delivering bad news and by experiencing it, encouraging students and physicians in training to participate in this experience with family.” |

| “It is very important to learn through personal example, so that it would be useful to be present whenever a more senior/experienced person is breaking bad news.” |

| “General advice for training concerning conducting the dialogue within a proper framework should occur prior to ever delivering bad news on one's own.” |

| “I think that workshops in this matter at intern/resident retreats would be a good learning experience. Everybody should be comfortable in delivering bad news to families and in helping families through their grief.” |

DISCUSSION

We have found that breaking bad news to a patient or family is a powerful experience for doctors in training. Virtually all of our respondents could clearly remember 1 such conversation from early in their career. Its force is evident in their written comments and in the their discussion with a broad range of people about the effect it had on themselves, the patient, and the patient's family.

The circumstances in which our respondents gave bad news were difficult. They were inexperienced and had known the patient or family only briefly. Those that stepped forward usually did so because they felt that they were the most suitable (or knew the patient best among the caregivers), not because they felt more adept. A substantial number were asked to break the bad news by superiors or were chosen by default. Almost no one volunteered simply to gain experience.

Our respondents felt that skill in delivering bad news has the highest importance. It is a skill that they believed can be learned. They found the most valuable ways of learning to be observation, being observed, and feedback by a more-senior resident or attending. This is consistent with reports that trainees appear willing to accept guidance from those with more experience, and that such guidance appears to be effective.17–30

The reported sources and utility of supervision of our respondents is at best only partially encouraging. Planning and debriefing occurred in the majority of instances, and multiple sources of support were available, including attendings, fellow residents, nurses, social workers, clergy, and family. Nevertheless, there was either no planning or no debriefing in a substantial number of instances. Direct observation took place in a minority of instances and then only about half the time with a more-senior doctor. Observation by attendings was notably infrequent. Although this may have resulted in part from the exigencies of medical practice, it is accepted that more-senior doctors must be present the first time that a trainee performs a significant medical procedure, and it seems that the same standard should apply to giving bad news. This deficiency is all the more striking given the benefit the residents report from such direct observation and feedback.

Tulsky et al. had similar findings in a survey of residents' experiences conducting do-not-resuscitate (DNR) discussions with patients. Their house staff reported averaging 1 DNR discussion per week while on the inpatient general medical wards, but one third of the residents had never been observed talking to patients about the issue. These researchers obtained audiotaped DNR discussions on a subset of the trainees they had surveyed. The quality of the audiotaped discussions was rated as poor, contrasting sharply with house staff self-perceived comfort and skill in this area. The authors conclude, as we do, that such findings are the result in part of a lack of supervised learning applied to communication skills training.33

Surprisingly, the respondents in our survey who delivered bad news first as students did not receive much more support than those who did so as residents. Attendings did not observe students more often, and higher-level trainees were present infrequently. Although students felt less well prepared, they were no more likely to have planning discussions. They felt that they responded less well to patients and family but, surprisingly, did not conclude significantly more often that they would change their approach in the future. While the majority felt that more supervision would be beneficial, they did not hold this opinion any more frequently than did those with more training. Thus, our respondents who were the least experienced at the time they first delivered bad news were not offered much more in the way of supervision, do not appear to have sought out much additional supervision, and rate their performance less highly, yet seem as ready to accept their first experience as a satisfactory template for future conduct.

Our findings have implications for training and supervision. First, there is significance to the fact that the events we describe can usually be anticipated and that they most often are localized to the medical wards and the intensive care unit. Hence, we should be able to plan for these encounters and assure that adequately trained personnel are available to perform the task or supervise those who are not yet ready to act independently. In this there is a similarity to bedside invasive procedures. Although important differences exist, the analogy may be helpful in considering how to improve training and supervision of those who give bad news to patients or families: When planning ahead, it is possible to decide upon a time and place, and determine who will take the lead, what should be said, what issues are likely to arise, how to respond, what level of supervision is appropriate, who else should be present, and when to meet afterwards for review and feedback. These elements correspond closely to those involved in the oversight of invasive procedures. Other points of similarity include the advisability of observing before doing, giving junior trainees an opportunity to be present when appropriate, ensuring that the supervisor has adequate skill, and intervening if sufficient problems arise.

We suggest that planning should be overseen by an attending, with delegation of authority to residents as governed by the concept of graded levels of responsibility. However, giving bad news can be forbidding even for senior physicians and consideration should be given to faculty training for those who do not feel comfortable or who might profit otherwise.

There are some general benefits that are likely to accrue from the increased emphasis on training that we propose. It should raise consciousness and increase sensitivity in giving bad news when this occurs during off hours (when direct supervision is less practical) and increase the likelihood that review and discussion will follow. In addition, the attentiveness given to the concerns of patients and family is likely to spill over into other aspects of practice. Finally, we will meet our responsibility to address an important source of emotional distress in a way that benefits both patients and doctors in training.

Our findings may be somewhat limited in generalizability because they derive from only 2 training programs in the same northeastern U.S. city. However, our cohort of residents has exposure to multiple hospitals that employ several hundred faculty. Furthermore, if one considers experiences in medical school, the dozens of individual schools represent a much broader subset of institutions.

Our retrospective, self-reported data based on single, best-recollected encounters may suffer from recall bias, because the most extreme encounters, whether good or bad, are most likely to be remembered. In addition, the response rate to our questionnaire was 61%. These facts must temper our conclusions, but still permit an informative first view of an important aspect of training. Despite these caveats, we believe the data to be an accurate reflection of current practices, based on our own training experiences, discussions with numerous trainees, and consistency with previous reports.

Skill in giving bad news is of great importance. As with other aspects of clinical medicine, it can only be mastered by doing. Supervision is integral to the process, both for the patients and to foster learning. We have found that the earliest experiences of giving bad news were infrequently observed by more-senior physicians. This diverges from the standards of supervision that apply to other important interventions, while it also deprives both students and residents of the kind of instruction that they find most helpful.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sherri BD. Cold hard death, cold hard doctors. Can Med Assoc J. 1992;146:560–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Personal view, an open letter to my surgeon. BMJ. 1992;305:62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox JL. Caring for the dying: reflections of a medical student. Can Med Assoc J. 1987;136:577–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dosanjh S, Barnes J, Bhandari M. Barriers to breaking bad news among medical and surgical residents. Med Educ. 2001;35:197–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlton RC. Breaking bad news. Med. J. Aust. 1992;157:615–21. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1992.tb137405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fallowfield L. Giving sad and bad news. Lancet. 1993;341:476–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miranda J, Brody RV. Communicating bad news. West J Med. 1992;156:83–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maguire P, Faulkner A. Communicate with cancer patients: 1. Handling bad news and difficult questions. BMJ. 1988;297:907–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6653.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quill TE, Townsend P. Bad news: delivery, dialogue, and dilemmas. Arch. Intern Med. 1991;151:463–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW. Breaking bad news: consensus guidelines for medical practitioners. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2449–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.9.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chisholm CA, Pappas DJ, Sharp MC. Communicating bad news. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:637–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espinosa E, Baron-Gonzalez M, Zamora P, Ordonez A, Arranz P. Doctors also suffer when giving bad news to cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1996;4:61–3. doi: 10.1007/BF01769878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckman R. How to Break Bad News: A Guide for Health Care Professionals. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW. Breaking bad news 1: current best advice for clinicians. Behav Med. 1998;24:53–9. doi: 10.1080/08964289809596381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maynard DW. How to tell patients bad news: the strategy of “forcasting”. Cleve Clin J Med. 1997;64:181–2. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.64.4.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ptacek JT, Eberhardt TL. Breaking bad news: a review of the literature. JAMA. 1996;276:496–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg A, Buckman MB, Kason Y. Teaching medical students how to break bad news. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;156:1159–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cushing AM, Jones A. Evaluation of a breaking bad news course for medical students. Med Educ. 1995;29:430–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1995.tb02867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearse P, Cooper C. Breaking bad news. Med. J. Aust. 1993;158:137–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb137554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knox JDE, Thomson GM. Breaking bad news: medical undergraduate communication skills teaching and learning. Med Educ. 1989;23:258–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1989.tb01541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrahill M. Giving bad news compassionately: a 2-hour medical school educational program. J Emerg Nurs. 1997;23:496–8. doi: 10.1016/s0099-1767(97)90153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luber MP. Overcoming barriers to teaching medical housestaff about psychiatric aspects of medical practice. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1996;26:127–34. doi: 10.2190/Y2UH-AY7C-P26G-9FVY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenberg LW, Ochsenschlager D, O'Donnell R, Mastruserio J, Cohen GJ. Communicating bad news: a pediatric department's evaluation of a simulated intervention. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1210–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaidya VU, Greenburg LW, Patel KM, Strauss LH, Pollack MM. Teaching physicians how to break bad news: a 1-day workshop using standardized parents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:419–22. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baile WF, Lenzi R, Kudelka AP, et al. Improving physician-patient communication in cancer care: outcome of a workshop for oncologists. J Cancer Educ. 1997;12:166–73. doi: 10.1080/08858199709528481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baile WF, Kudelka AP, Beale EA, et al. Communication skills training in oncology. Description and preliminary outcomes of workshops on breaking bad news and managing patient reaction to illness. Cancer. 1999;86:887–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rappaport W, Witzke D. Education about death and dying during the clinical years of medical school. Surgery. 1993;113:163–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makoul G. Medical student and resident perspectives on delivering bad news. Acad Med. 1998;73(suppl):35–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199810000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jolly BC, MacDonald MM. Education for practice: the role of practical experience in undergraduate and general clinical training. Med Educ. 1989;23:189–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1989.tb00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dent THS, Gillard JH, Aarons EJ, Crimlisk HL, Pigott PJS. Preregistration house officers in the four Thames regions: I. Survey of education and workload. BMJ. 1990;300:713–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6726.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eggly S, Afonso N, Rojas G, Baker M, Cardozo L, Robertson RS. An assessment of residents' competence in the delivery of bad news to patients. Acad Med. 1997;72:397–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199705000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludmerer KM. Learning to Heal. New York: Basic Books; 1985. pp. 175–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tulsky JA, Chesney MA, Lo B. See one, do one, teach one. House staff experience discussing do-not-resuscitate orders. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1285–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.156.12.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]