Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The Ethical Force Program is a collaborative effort to create performance measures for ethics in health care. This report lays out areas of consensus that may be amenable to performance measurement on protecting the privacy, confidentiality and security of identifiable health information.

DESIGN

Iterative consensus development process.

PARTICIPANTS

The program's oversight body and its expert panel on privacy include national leaders representing the perspectives of physicians, patients, purchasers, health plans, hospitals, and medical ethicists as well as public health, law, and medical informatics experts.

METHODS AND MAIN RESULTS

The oversight body appointed a national Expert Advisory Panel on Privacy and Confidentiality in September 1998. This group compiled and reviewed existing norms, including governmental reports and legal standards, professional association policies, private organization statements and policies, accreditation standards, and ethical opinions. A set of specific and assessable expectations for ethical conduct in this domain was then drafted and refined through 7 meetings over 16 months. In the final 2 iterations, each expectation was graded on a scale of 1 to 10 by each oversight body member on whether it was: (1) important, (2) universally applicable, (3) feasible to measure, and (4) realistic to implement. The expectations that did not score more than 7 (mean) on all 4 scales were reconsidered and retained only if the entire oversight body agreed that they should be used as potential subjects for performance measurement. Consensus was achieved on 34 specific expectations. The expectations fell into 8 content areas, addressing the need for transparency of policies and practices, consent for use and disclosure of identifiable information, limitations on information that can be collected and by whom, individual access to one's own health records, security requirements for storage and transfer of information, provisions to ensure ongoing data quality, limitations on how identifiable information may be used, and provisions for meaningful accountability.

CONCLUSIONS

This process established consensus on 34 measurable ethical expectations for the protection of privacy and confidentiality in health care. These expectations should apply to any organization with access to personally identifiable health information, including managed care organizations, physician groups, hospitals, other provider organizations, and purchasers. Performance measurement on these expectations may improve accountability across the health care system.

Keywords: health policy, health care information

Today, every participant in health care delivery can be affected by the ethical standards of many other participants. But ethical standards are derived from value systems, and in contemporary health care, there are business, public health, personal, and medical professional ethical values at work; and all, from time to time, may conflict. It has been suggested that health care requires a “mutual and multilateral web of accountability for ethics” among all its participants.1 Such an accountability matrix might better balance diverse values to create shared expectations for ethical behavior. For such an accountability matrix to succeed, it must be possible to evaluate who is living up to these shared expectations and who is not. That is, performance measures for each domain of ethics are necessary. The Ethical Fundamental Obligations Report Card Evaluations Program (E-Force) was created to address this issue.2 Its mission is to develop performance measures for domains of ethics that can be applied to all participants in health care delivery. The program was created in broad collaboration with numerous participants in the health care delivery system (Appendix 1).2

One of the first domains of health care ethics selected by E-Force for performance measure development was the protection of health care informational privacy.2 This area is important because improved access to relevant health care information can increase efficiency, improve patient outcomes, and allow for better protection of public health and safety.3–7 Indeed, some computerized medical information systems have been shown to reduce mistakes, lower costs, and improve quality of care.5,8 At the same time, however, justifiable concerns have been raised regarding the confidentiality of sensitive medical information,9–14 leading the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics to declare in 1997 that “the United States is in the midst of a health privacy crisis.”10 Although Bukovich et al. recently documented some widely accepted basic norms regarding privacy protection in health care,15 other research suggests that few uniform standards and practices are now in place.16,17

Concerns about privacy and confidentiality in medicine are well founded in part because health information privacy norms appear inconsistent at best.18–20 Numerous anecdotes and some data support that some employers use health care information to make employment-related decisions.20–23 Individually identifiable health information has been released to the public and sold or traded to others, without patient consent, for purposes such as direct marketing campaigns, and by accident or malice.3,21,23–25 In addition, the protection of patient confidentiality is taking on increased urgency with the advent of electronic communications and record-keeping, especially the use of the Internet.14,26 The desirability and feasibility of developing large data systems to improve research, monitoring, and quality increases the demand for strong privacy protections so that appropriate projects can move forward safely.27 Also, while electronic systems provide some opportunities to protect sensitive information—through such mechanisms as user authentication, encryption technologies, and audit trails28–30—computerization may also allow quiet and rapid breaches of confidentiality, potentially on massive scales, which further increases the importance of implementing strong protections.21,28,31–37

In response to these concerns, many individuals and groups—especially medical researchers, public health officials, and health care delivery organizations—counter that overzealous or misdirected privacy protections could thwart efforts to use information to improve patient care and public health. They note that the vast majority of patients, when they are asked, agree to let their records be used for “legitimate” purposes, such as biomedical research approved by an Investigational Review Board (IRB).38 Similarly, the use of identifiable health information to protect the public, such as public health reporting requirements for communicable diseases, is well accepted23,39 In addition, the cost of implementing some privacy protections has come under criticism,40,41 as has their potential impact on employer-sponsored disease management programs,42 patients' family members,43 and medical research.38,44

Fortunately, in the midst of these conflicting concerns, areas of agreement exist. For example, it is generally agreed that health care is improved when patients are willing to confide sensitive personal information to their caregivers and that patients who doubt the security and confidentiality of their information may not tell practitioners all they need to know to make appropriate treatment recommendations.3,15,45–47 Thus, individuals who are worried about confidentiality may refuse potentially beneficial testing or treatment; they may ask practitioners to keep separate records or not to report certain data; or they may even avoid care entirely.3,19,48,49 Each of these “privacy protective” responses can seriously impair health care delivery.

Another area of agreement—beyond the practical benefit that confidentiality may increase individuals' willingness to disclose useful information to health care practitioners—is that certain widely shared norms argue for protecting sensitive health information.50–52 Interest in informational privacy rests on fundamental beliefs in the importance of autonomy and fairness. Respecting autonomy means allowing individuals to make decisions that affect their person, i.e., who they are, how they present themselves to others, and what they do. Because health information may affect how one is perceived and treated by others, individuals have a clear interest in what health information about them is disclosed, to whom, and for what purposes. Respecting fairness means that, among other things, individuals should be given the information necessary to make important decisions. Thus, individuals must know the uses to which their health records will be put and how they will be protected from further disclosure, before it is fair to ask them to decide whether to confide health information to others.

In this project, the E-Force program rigorously explored these areas of agreement to create some specific and measurable shared expectations for the protection of individually identifiable patient information throughout the health care system.

METHODS

Creation and validation of performance measures for ethics can be achieved using a stepwise approach.2 Large domains of ethics may be broken down into relevant content areas.53 Then each content area can be delineated in terms of specific expectations for each of the parties to health care delivery. Finally, performance measures based on these expectations can be created and tested for their reliability, validity, and feasibility of implementation. Hence, testing in this stepwise approach occurs in two phases. First, the content areas and specific expectations must be assessed for their content validity, i.e., according to the relevant experts, are all areas covered that should be and none included that should not be?54,55 Second, the performance measures themselves must be created and field-tested to determine their criterion and construct validity as well as their reliability and feasibility for use.55

Steps in the Consensus Process

The Expert Advisory Panel

To accomplish the first stage of development and validation, the E-Force oversight body in the summer of 1998 appointed an Expert Advisory Panel on Privacy and Confidentiality (EAP) consisting of experts in medicine, privacy, ethics, law, accreditation, informatics, and public health (Appendix 2). The charge of the EAP was to examine existing norms for privacy protections and to suggest potentially measurable expectations for performance on protecting the privacy and confidentiality of health information. The EAP reviewed literature and existing policies, using meetings, conference calls, and e-mail to facilitate communication among EAP members.

Adoption of Definitions

Popular conceptions of privacy tend to group many kinds of privacy interests together, yet privacy has an extensive conceptual and legal history with many distinctions and subtleties.4,11,31,47,52,56–59 For this report, privacy is taken to be the interest individuals have in their personal control over sensitive aspects of their lives, such as information about personal health. “Informational privacy” specifically encompasses an individual's interest in disclosing personal information to others and for what purpose(s).27,52,56,57“Health informational privacy” pertains to information about one's health status or history.

When an individual directly or indirectly discloses private information to another, the recipient of the information should hold it in “trust.” In this report, an “information trustee” is any person or organization entrusted with identifiable health care information. Such information requires protection to prevent its further dissemination or use against the wishes of the information source and this protection is the condition, or promise, of confidentiality.50 Confidentiality is thus a condition that is established to protect privacy. “Confidentiality safeguards” consist of the policies and procedures that control the sharing and release of information that has been entrusted to another party by an information source.7,57

Finally, “security” encompasses the set of technical and administrative procedures and policies that protect confidential information from loss or unauthorized disclosure, access, destruction, alteration, or use. Security measures are applied to the people, information, and technologies that collect, store, and use information; they are tools used to implement the promised condition of confidentiality.

Consensus Development

In June 1999, after completing a literature review, the EAP reported to the oversight body that the ethical domain of health care informational privacy should be broken down into 8 content areas, and it suggested a large number of potentially measurable expectations to consider for each content area. The oversight body reviewed, and suggested revisions to, the content areas and expectations. A revised set of expectations was then circulated to the EAP and the oversight body; each member graded each expectation from 1 to 10 in 3 areas, addressing the importance and universal applicability of the expectation and the feasibility of meeting the expectation. Those that fell below a mean score of 7.5 on any single rating scale were reconsidered by the EAP and many were eliminated. This newly revised set of expectations was then sent to oversight body members for another set of grades on whether each was: (1) important, (2) universally applicable, (3) feasible to measure, and (4) realistic to implement. Oversight body members were free to engage colleagues at their home institutions when assigning grades. Expectations that did not rate a mean score greater than 7 on all 4 scales were reconsidered at an oversight body meeting in January 2000, and several were combined, revised, or eliminated. In the end, expectations were retained only if the entire oversight body agreed that they should be used as potential subjects of performance measurement. Some were retained with recognition that they might be difficult to measure, because the only way to assess whether such difficulties will arise is to develop measures based on these expectations and then field-test the measures.

RESULTS

Sources of Norms for Health Information Protections

The EAP reviewed numerous documents that have described norms for privacy and confidentiality protections. One of the earliest and most influential documents was the 1973 report from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Secretary's Advisory Committee on Automated Personal Data Systems, “Records, Computers, and the Rights of Citizens.”60 This report stated that: (1) personal data record-keeping systems must not be secret; (2) individuals must be able to find out what information about them is in a record and how it is used; (3) individuals must be able to prevent information about them from being used without their consent; (4) individuals must be able to correct or amend their records; and (5) organizations creating and using record systems must assure their reliability and protect them from misuse. In 1974, the Privacy Act (5 U.S.C. §552a) was enacted. It is largely based upon the 5 norms set out in this 1973 report, which have become known as Fair Information Practices (FIP).45

The FIP norms have been used by other countries to form the basis of their own data protection laws,61,62 including the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development “Guidelines Governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data,” which were issued in 1980 and adopted by the United States.63 The norms in this document fall into 8 categories: collection limitation, data quality, purpose specification, use limitation, security safeguards, openness, individual participation, and accountability. More recently, the European Union (EU) Directive on the Protection of Personal Data went into effect in October 1998, which requires that non-EU countries have in place “adequate” data protection mechanisms (again, based on the FIP) before receiving personal information from EU countries.

In the United States, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) acknowledged the increasing computerization of medical information by codifying requirements for the electronic management of health information.64,65 In addition, HIPAA called on the Congress to pass legislation to protect individually identifiable health information.31 In the 105th Congress, several legislative proposals were introduced in both the House and the Senate, but the legislative future of these various bills remains uncertain. In the absence of passed legislation, in November 1999, the Secretary of Health and Human Services provided a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, which proposed rights that individuals should have with respect to their health information, procedures to exercise these rights, and authorized/required uses and disclosures of the information.66 A revised version of these rules is to be released late in 2000.

Private sector organizations have also been considering these issues, with resulting model legislation, organizational policy statements, and model policies and procedures. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and the National Committee for Quality Assurance in late 1998 released a joint publication67 and recommendations from this document are now making their way into accreditation standards.68 The Model State Public Health Privacy Project has created model state health privacy legislation.69 The Health Privacy Project at Georgetown University is sponsoring several initiatives, including the Health Privacy Working Group whose report, “Best Principles for Health Privacy,” was released in 199970 along with a “consumers' guide” to protecting health privacy.20

Professional associations are also concerned. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners adopted its Health Information Privacy Model Act in 1998.71 The American Medical Association House of Delegates has passed new privacy policies at each of its last 3 meetings.72,73 The American Bar Association governing body adopted new health privacy recommendations in early 1999 and has established an Electronic Communications and Privacy Interest Group to tackle legal issues surrounding electronic communication and privacy.74 The American Association of Health Plans recently revised its recommended member policies on the protection of patient privacy and record confidentiality as part of its “Putting Patients First” initiative.75 Numerous other patient and professional groups have recently revised, reconsidered, or created new privacy policies.42,46,62,67,71,76–79 Many of these documents from the United States and abroad reflect fundamental concerns over how health care is adapting to the information revolution.26,80

Content Areas and Associated Expectations for Privacy and Confidentiality Protections

Working from the above codes, principles, and research, E-Force achieved consensus on the following expectations for the protection of health information privacy and confidentiality. Broken into 8 general content areas, each area is accompanied by a set of specific measurable expectations, shown in Tables 1 through 8.

Table 1.

Consensus Expectations for the Content Area, “Transparency”

| Health information trustees should make publicly available clear explanations of their policies, procedures, and practices regarding the collection, storage, and use of personally identifiable health information. |

| Expectations |

| 1.1 The health information trustee makes publicly available, in clear and understandable language, general descriptions of its policies and practices regarding the collection, storage, and use of identifiable health care information. |

| Policies disclosed include: |

| a) Classifications of who will have access to the information collected |

| b) What general measures are used to protect the security of health information |

| c) Under what sorts of circumstances personally identifiable information might be used or accessed without the individual's consent for nontherapeutic purposes |

| d) How the integrity and quality of the data will be ensured |

| e) The procedures through which individuals may obtain access to their own identifiable health information |

| f) The procedures through which individuals may suggest amendments to be appended to their record(s) |

| g) Any rights of redress an individual has to address breaches of privacy, security, and confidentiality policies |

| h) What/who is/are the organizational point(s) of contact for privacy, security, and confidentiality concerns |

| i) In general, how long identifiable information will be held, including general descriptions of organizational policies on data destruction and deidentification |

| 1.2 The information in 1.1 is periodically updated and redistributed. If significant changes occur in policies or procedures, especially any changes that could result in nonconsensual accessing, disclosure, or use of personally identifiable health information, relevant parties are notified of such a change. |

Table 8.

Consensus Expectations for the Content Area, “Accountability”

| Health information trustees should be accountable for adhering to standards for the collection, storage, and use of personally identifiable health information, including the responsible transfer of information to other accountable information trustees. |

| 8.1 Health information trustees furnish clear policies and materials to all of their agents who have access to identifiable health information to support their training in the proper handling of sensitive health information. |

| 8.2 Health information trustees ensure that individuals handling identifiable health information are properly trained, on a regular basis, in their security and confidentiality standards, including requirements that are specific to each individual's job. |

| 8.3 Reprimands, feedback, education, probation, and other appropriate methods are used to enforce adherence to privacy and confidentiality protection standards. |

| 8.4 Written policies specify what level of penalty will result from specific breaches of privacy and confidentiality protections. |

| 8.5 Individuals with access to identifiable health information display knowledge of protections afforded this information and the penalties associated with breaching the security or confidentiality of this information. |

| 8.6 Health information trustees have in place a formal internal mechanism for individuals to bring forth, without fear of reprisal, complaints of inappropriate collection, storage, or use of personally identifiable health information. |

| 8.7 When an internal review mechanism does not provide a satisfactory resolution, there is an opportunity for external review of unresolved privacy complaints. |

| 8.8 Health information trustees, unless otherwise prevented by law, require a written statement of adherence to privacy, security, and confidentiality standards from all employees, agents, subcontractors, and outside organizations who wish to gain access to protected health information. |

Content Area 1. Transparency

Health information trustees should make publicly available clear explanations of their policies, procedures, and practices regarding the collection, storage, and use of personally identifiable health information.

Patients and others need accurate information to make informed decisions about when, how often, how much and what types of identifiable health information to confide to others. Fears of misuse of sensitive health information rise when privacy policies are not known, potentially leading some patients to decline useful testing or treatment. Moreover, if informational privacy policies are open to scrutiny, then information trustees will carefully consider what those policies should be. Thus, even if few individuals avail themselves of the opportunity to learn the details of an organization's policies and practices, their ability to do so can serve a useful purpose.

The complexity of confidentiality protections in the evolving health care system demands that the process of transparency involve the ongoing and coordinated efforts of numerous health information trustees, including employer/purchasers, health care delivery organizations, practitioners, and others. For example, purchasers such as employers might help health plans to explain and publicize that patients/beneficiaries have the right to access and copy their health care records (Table 1).

Content Area 2. Consent

Whenever feasible, health information trustees should obtain valid informed consent from individuals for the collection, storage, or use of personally identifiable health information. If consent is not obtained, then a formal, authoritative, and publicly accountable process must be used to authorize a waiver of consent.

With an individual's valid informed consent, uses of identifiable health information are generally justifiable. Refusal of consent should be respected in the same way. In only 2 circumstances may consent be presumed. First, consent for use of information for the direct therapeutic benefit of a patient may be presumed when the patient presents for care. However, even then the patient may request constraints, and if this is not possible, then health information trustees should so inform the patient. Second, consent for use of information for payment purposes may also be presumed, but only when a patient presents to a plan for care or submits a bill for reimbursement.

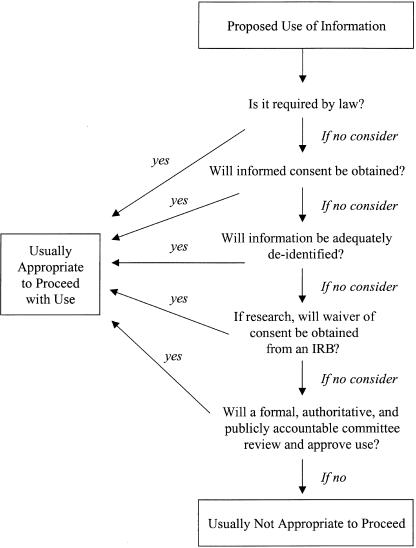

Figure 1 shows a series of considerations for any proposed use of health information that is not for payment or direct patient care. Most important is that whenever deidentification or informed consent is not obtained, then a formal, authoritative, and accountable committee should be charged with reviewing the situation and, if appropriate, authorizing a waiver of the personal informed consent requirement. For some research uses, including some health services research, an IRB already performs such a review.81 For example, research that involves collecting and using data to assess patterns of care delivery often is reviewed by an IRB, in part to ensure that data are deidentified as soon as possible and to ensure anonymity in public reporting of results. For many other uses of identifiable data, including nongovernment-sponsored research, quality assurance and improvement projects, disease management programs, and some public health practices, IRB review is not common. For these, another formal review mechanism may need to be involved. In many organizations, an existing entity, such as a privacy board or a medical records committee, could serve this role. Where an existing and appropriate committee does not exist, organizations might create a Data Disclosure Board,82 especially to review proposed uses of identifiable information where individual consent will not be obtained.

FIGURE 1.

A process to determine appropriate nontherapeutic uses of personally identifiable health information. Consent for uses of information for the direct therapeutic benefit of the patient or for payment may frequently be presumed (see text). †Institutional Review Board.

Any reviewing committee that is authorized to waive personal informed consent requirements, whatever its name and composition, should undertake careful deliberations and be accountable for its decisions. Specific expectations such as reviewing data needs assessments and privacy impact assessments are listed in Table 2). These documents should be created by the data requester and should answer questions such as the following: (1)Will the least intrusive means feasible be used to collect information? (2)Are all reasonable steps being taken to ensure that the least identifiable (i.e., the most difficult to link to an individual) information is used that is consistent with the stated purpose? (3)Might the potential or real vulnerability of patients be exploited in collecting or using the information? (4)Might patients' direct care be negatively affected? and (5)Is the most complete notice possible being made to the persons whose information is involved?

Table 2.

Consensus Expectations for the Content Area, “Consent”

| Whenever feasible, health information trustees should obtain valid informed consent from individuals for the collection, storage, or use of personally identifiable health information. If consent is not obtained, then a formal, authoritative and publicly accountable process must be used to authorize a waiver of consent. |

| Valid informed consent |

| 2.1 Valid informed consent for collection, storage, and use of identifiable health information includes disclosure of all necessary information that a reasonable person would use in making an informed decision, in a format that is readily understandable to the individual, and without coercion influencing choice. The information conveyed includes the information described in Expectation 1.1 (a-i) |

| Process for waiver of informed consent |

| 2.2 Valid informed consent to the collection, storage, or use of personally identifiable health information is required, unless its waiver has been justified and authorized by an explicit formal mechanism that is publicly accountable. |

| 2.3 Health information trustees that collect, hold, disclose, access, or use personally identifiable health information without the valid informed consent of the subjects of the information (and not in the course of medical research reviewed by an Institutional Review Board or in the course of legal obligations) have in place a formal, authoritative, and publicly accountable process to address the necessity of doing so (such as a Data Disclosure Board). |

| 2.4 Written records are kept of the proceedings and decisions from this process. |

| Documentation of the process |

| 2.5 The process includes the careful review of a Data Needs Assessment (DNA) document, submitted by the data requestor, for any nonconsensual use of personally identifiable health information. A written DNA addresses the legitimate need for information to be collected, stored, or used without valid consent. |

| 2.6 The process includes the careful review of a written Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) document, submitted by the data requestor, for any nonconsensual use of personally identifiable health information. A written PIA addresses the risks and benefits to patients, beneficiaries, employees, and other stakeholders of the proposed collection, storage, and use of identifiable information without valid consent. |

| Opt-out provisions |

| 2.7 Patients are allowed to deny the release of their identifiable health information outside the organization receiving the information, except as required by law or as approved through a formal authorization process that is publicly accountable. |

| 2.8 The health information trustee has clear and public policies on what uses of health information are not optional. |

The E Force group recognizes that some small organizations and individual health information trustees may only infrequently use identifiable health information for other than routine therapeutic and quality assessment/quality improvement activities. Such entities might choose to: (1) group together with other organizations to create a review committee and provide peer-oversight; (2) adopt standard practices and policies that are developed nationally, regionally, or by a health care delivery organization with which the organization contracts; and/or (3) avoid use of patient-identifiable information for nontherapeutic purposes unless personal informed consent is obtained. In addition, practices and projects that are ongoing and routine (such as the use of identifiable patient information during morbidity and mortality conferences) should not face repeated reviews over short periods of time. A reasonable approach would be to rescreen ongoing and routine practices on an annual or biannual basis. Finally, though current laws vary,16 law enforcement access to personal health information should operate under the same principles as law enforcement access to other personal property and information. Access should generally require probable cause and a court order. In addition, when personally identifiable health information is required by a legal authority without seeking individual consent, a written notice should be given to the legal authority that: (1) notes the confidential nature of the data that is being disclosed; (2) requests disclosure of the least intrusive data possible; (3) requests that the legal authority adhere to standards in its storage, redisclosure, and use of the data; and (4) requests that the legal authority either return the data or destroy it when it is no longer necessary for the intended purpose.

Content Area 3. Collection Limitation

Health information trustees should limit collection of health information to that information required for current needs or reasonably projected future needs, which are made explicit at the time consent is obtained.

Except where required by law, personally identifiable information to be used in undefined future circumstances should not be collected or stored without individual informed consent because this poses a risk to privacy for an uncertain benefit. In addition, individuals who are asked to provide information that appears to be irrelevant to stated purposes may develop concerns that the information is intended for unauthorized, unstated, or even hidden purposes.

To act on this norm, individuals charged with collecting, storing, and using identifiable health information should receive training on collection limitations (Table 3) This training should include the following: health information trustees should collect and maintain only identifiable health information that is necessary for patient care and other authorized purposes, and patients, when they go outside of a health plan and pay out of pocket for care, are entitled to not release this information to health plans or others except as required by law. Clinicians, when acting in their role as caregivers and patient advocates, should not be called upon to collect information that is not relevant, in the clinician's professional judgment, to the direct therapeutic or diagnostic benefit of the patient. Professional judgment is especially important when clinicians participate in public health activities that may only occasionally confer direct benefit to the individual patient, since appropriately authorized public health activities can form important and legitimate uses of identifiable information. The training should also cover specifically what information is considered to be “personally identifiable” (see also Content Area 4).

Table 3.

Consensus Expectations for the Content Area, “Collection Limitations”

| Health information trustees should limit collection of health information to that information required for current needs, or reasonably projected future needs, which are made explicit at the time consent is obtained. |

| 3.1 All data collectors receive training in collection limitations, including fair and lawful means to collect information and the rationales for limiting data collection. |

| 3.2 The health information trustee has a written policy on health information retention and destruction that specifies whether and how identifiable health information that is not reasonably expected to be used for 1 or more defined purposes is to be discarded, deidentified, or archived. |

Content Area 4. Security

Health information trustees should protect the identifiable health information in their care using reasonable security measures appropriate to the sensitivity of the information. A specific individual or group should be identified as being responsible for overall security mechanisms and processes.

Individuals are reasonably entitled to demand stringent security measures for their personally identifiable health information, regardless of whether the information is used for direct patient care, payment, or other purposes. Moreover, though the risks of unauthorized access, use or modification of data may be difficult to quantify, the potential harms can be grave. Effective security measures can reassure patients that their personal information will be safe. In particular, it is the responsibility of each information trustee, through its security officer or team, to determine and implement appropriate deidentification measures for data, which may vary according to the information, its use, and who is using it. Deidentification is complex, and one simple measure will not suffice for all potential uses of information. However, adequate deidentification is necessary for many reasons, such as allowing the use of aggregate data for quality assessment and improvement projects without imperiling individual privacy interests.28–30

Content Area 5. Individual Access

Individuals should be allowed access to view and amend or append information to their personally identifiable health information records.

Individuals retain legitimate interests in information that they have chosen to confide to others. For example, individuals should have a right to ensure that the recording of their information is accurate. Further, some health information derives from medical testing or other sources where the patient has less control over how much and what type of information is collected. Having access to and knowledge of this information may be vitally important to the patient's life plans and ability to make informed choices, including whether to consent to the release and use of these records. It is also important to know to whom one has entrusted sensitive information. As far as it is feasible, health information trustees should allow individuals to know who has gained access to their personally identifiable information and for what purpose(s).

Exceptions to patient access to their records may rarely occur due to legal requirements, as when information is held under court seal, when a confidential source of information exists, when the data contain information about other individuals (other than health professionals), or when minors or guardianships are involved. As a general rule, except in cases of endangerment, if information is being disclosed to a third party, then it should also be available to the subject of the information. “Professional privilege,” withholding information because a professional believes that disclosure would be dangerous to the patient or others, is rarely necessary. Usually, temporizing measures, such as requesting that the patient wait a few days for a “cooling off” period, are preferable to an invocation of professional privilege.

Content Area 6. Data Quality

Health information trustees should seek to ensure that the identifiable health information in their care is as accurate, complete, and up-to-date as is required for the purposes for which it is collected and used.

Health care information must be accurate, timely, and complete to ensure its effectiveness. Inaccurate information, such as an incorrect diagnosis, can harm individuals in unpredictable and distressing ways. It might also impair health care delivery by inappropriately diverting resources away from important needs. For example, if a patient's need for an organ is exaggerated, another patient may unfairly be denied the organ.

Content Area 7. Information Use Limitation

Health information trustees should limit the disclosure and use of personally identifiable health information to those purposes that are made explicit at the time consent is obtained or are otherwise authorized through a formal, authoritative, and publicly accountable process.

Any use of health information to fulfill a purpose other than that for which consent was obtained is a breach of the individual's interest in maintaining their informational privacy, which jeopardizes both the individual's personal dignity and trust in the health information trustee. Any such breach must be justified through an accountable waiver of consent process as described above. The primary concerns of the items in Table 7)are to ensure that nonconsensual uses of identifiable health information are justified and limited such that they do not: (1) inhibit patients from confiding information necessary for their own therapeutic benefit; (2) exploit patient vulnerability; or (3) impede the collection, storage, or use of information for authorized purposes.

Table 7.

Consensus Expectations for the Content Area, “Information Use Limitations”

| Health information trustees should limit the disclosure and use of personally identifiable health information to those purposes that are made explicit at the time consent is obtained or are otherwise authorized through a formal, authoritative, and publicly accountable process. |

| 7.1 Identifiable information that is collected for a defined purpose is not used for another purpose without explicit consent, unless legally required or else authorized through a process allowing waivers of consent for the use of health information (such as a Data Disclosure Board). |

| 7.2 Access privileges among individual employees and contractors of a health information trustee are directly tied to the necessity of access to the information for the individual's job functions. |

| 7.3 There is no commercialization (sale or exchange for commercial purposes) of identifiable health information without the informed consent of the individuals whose information is involved. |

| 7.4 Health information trustees have in place written policies that describe the circumstances and documentation necessary to authorize the release of identifiable health information to law enforcement officials. |

| 7.5 When a patient's identifiable health information is subpoenaed, the trustee notifies the patient with as much advance notice as can reasonably be given. |

Content Area 8. Accountability

Health information trustees should be accountable for adhering to standards for the collection, storage and use of personally identifiable health information, including the responsible transfer of information to other accountable information trustees.

Protection of health care informational privacy involves ensuring the accountability of a wide array of parties on a variety of topics related to the collection, storage, and use of personally identifiable health information. It can involve legal, economic, and professional enforcement mechanisms.83 Despite this variability, as health care information passes from one person or organization to another, lapses of accountability could have dramatic consequences for all. Failure in any part of this “chain of accountability” could lead to individuals choosing not to confide information to other links in the chain, making the responsible efforts of these latter parties moot. Therefore, it is important to seek high levels of accountability among all health information trustees. Unauthorized access to, disclosure of, or use of personally identifiable health information should lead to a commensurate and consistent response regardless of the status or type of the offending party.

While health information trustees are accountable primarily for their own attention to the protection of individuals' privacy interests, the system of privacy protections will not be effective if information transferred outside a responsible trustee does not receive continuing protection. Therefore, assuring this continuing protection is partially the responsibility of the trustee transferring the information. This obligation will be met if each entity receiving identifiable data from another health information trustee will promise to meet these expectations (Table 8).

DISCUSSION

Better use of health care information can improve quality, avoid errors, and increase efficiency in health care. At the same time, individuals and society have strong interests in protecting the confidentiality of information disclosed to medical practitioners and insurers. Indeed, ensuring confidentiality may be a prerequisite for accurate information exchange. To address this issue, we created a consensus process to establish specific expectations that can be applied to all participants in the health care system.

While the consensus process and expectations outlined in this report are unique, they should be seen in context. Other groups are making similar recommendations, suggesting an emerging social consensus around many of these expectations, e.g., all uses of identifiable health information, including uses in health services research, quality improvement projects, and disease management programs, should be reviewed by an accountable review committee, and all users of identifiable health information should be trained in confidentiality and security practices.67,69,81 This larger consensus is important because the utility of the expectations listed relies on widespread acceptance and, eventually, the use of the performance measures built around them to ensure that the expectations are being met.2 Still, we recognize that in some areas our expectations are only rarely being met today and barriers to meeting these expectations may exist. For some of the expectations listed, creating valid and reliable measurement of whether an organization is living up to the expectation will be challenging. But as a first step, the rigorous, multilayered consensus process used to establish the expectations listed in the tables provides them with face validity as important areas for performance measurement.55 The expectations are also specific enough to support performance measure development, so that practitioner and patient survey items, site review criteria, and policy review criteria could be used to assess whether these expectations are being met.

In keeping with the unique mission of the Ethical Force Program, performance measures are now being created based on these expectations, which will be assessed for test-retest and interrater reliability, context, and, where possible, criterion validity before they are released for use.2,55 In the meantime, the expectations outlined in this consensus report can provide guidance to all participants in health care delivery—from physicians to health plans and medical groups, and from hospitals to employers and other purchasers—because they represent a documented convergence of values among these diverse participants in health care delivery.

Table 4.

Consensus Expectations for the Content Area, “Security”

| Health information trustees should protect the identifiable health information in their care using reasonable security measures appropriate to the sensitivity of the information. A specific individual or group should be identified as being responsible for overall security mechanisms and processes. |

| Written policies |

| 4.1 Health information trustees have written policies that delineate the security measures used to protect identifiable records from risks such as loss or unauthorized access, destruction, use, modification, or disclosure. |

| Security of information stored and transmitted on paper |

| 4.2 Health information trustees have physical security measures in place where paper records are used to ensure that: |

| a) Areas where health information is stored physically (e.g., record rooms, file cabinets, etc.) are locked when not attended. |

| b) There is a mechanism to sign out and track the whereabouts of physical records. |

| c) A record is maintained to track instances where clinical records are copied and distributed. |

| d) Identifiable health information is not visible in public areas. |

| Security of information stored and transmitted electronically |

| 4.3 Health information trustees have electronic security measures in place where electronic records are used, to ensure that: |

| a) Identifiable data is encrypted for any external transfer over the Internet. |

| b) Automated access controls and user profiles are in place in any computer or computer system storing identifiable medical information. |

| c) User-friendly audit trails are in use and checked regularly or randomly. |

| d) User authentication protections are in place (e.g., secret passwords or biometric identifiers). |

| e) Identifiable health information visible on computer screens is not easily read by public passersby, and computer screens are disabled when the user leaves his/her computer terminal. |

| Security officer or team |

| 4.4 Organizations that are health information trustees designate 1 or more specific individuals to be accountable for overall security measures, regular review of security issues and updating of security protocols (e.g., a security officer or team). |

| 4.5 The security officer, or other responsible party, does the following: |

| a) Performs or supervises periodic audits of health information security procedures to detect and prevent breaches in security |

| b) Defines and periodically updates mechanical and electronic deidentification procedures and oversees their use |

Table 5.

Consensus Expectations for the Content Area, “Individual Access”

| Individuals should be allowed access to view and amend or append information to their personally identifiable health information records. |

| 5.1 Except in specific and limited circumstances the health information trustee provides individuals access to review and copy their own identifiable health information. |

| 5.2 Should patients review their information and believe it to be incomplete or inaccurate, health information trustees allow individuals to suggest amendments, which will be appended to their records. There need not be a requirement to delete data that are inaccurate or incomplete; rather, corrected information may be added to the record with the date and source of the appended information marked. |

Table 6.

Consensus Expectations for the Content Area, “Data Quality”

| Health information trustees should seek to ensure that the identifiable health information in their care is as accurate, complete, and up-to-date as is required for the purposes for which it is collected and used. |

| 6.1 Health information trustees perform periodic audits to ensure the accuracy of identifiable health data. |

| 6.2 Health information trustees regularly review and evaluate their security and confidentiality measures to ensure that they do not unduly interfere in the timely and accurate transmission and receipt of information necessary for patient care. |

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this article represent the consensus of the Ethical Force Program's Oversight Body members as interpreted by the writing group of authors listed. The report may not reflect the positions of the members' or authors' affiliated organizations. Members of the Ethical Force Program's Expert Advisory Panel on Privacy and Confidentiality served in an advisory capacity to the Oversight Body. Neither their own nor their affiliated organizations' endorsement of the report should be inferred.

APPENDIX 1

The Ethical Force Program

Mission Statement

The Mission of the Ethical Force Program is to improve health care by fostering the ethical behavior of all participants. The Program identifies and promotes ethical expectations and performs research to develop valid and reliable measures of their achievement.

Mission Goals

Through the collaborative involvement of all major participants in health care, the Program aims to achieve 3 goals:

To identify and promote ethical expectations for all participants in health care

To develop valid and reliable measures of achievement of ethical expectations

To encourage the widespread adoption and use of these expectations and measures

Adopted by the E-Force Oversight Body on June 26, 1998.

APPENDIX 2

Members of the Oversight Body for the E-Force Program, 1999–2000

| (Organizational affiliation listed for identification purposes) |

| Linda L. Emanuel, MD, PhD |

| Northwestern Medical School |

| E-Force Program Founder |

| Robert Alpert |

| United Auto Workers |

| Michele Dennis, RN |

| American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees Union |

| Ezekiel Emauel, MD, PhD |

| National Institute of Health |

| Arnold Epstein, MD |

| Harvard School of Public Health |

| Larry Gage |

| National Association of Public Hospitals and Health Systems |

| Allan Korn, MD |

| National Blue Cross Blue Shield Association |

| John Ludden, MD |

| Harvard Medical School |

| Karen Milgate |

| American Hospital Association |

| Frank Riddick, MD |

| Alton Ochsner Medical Foundation |

| Neil Schlackman, MD |

| Aetna-US Healthcare |

| Linda Shelton |

| National Committee on Quality Assurance |

| David Tennenbaum (Alternate) |

| National Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association |

| American Nurses Association |

| John Eisenberg, MD |

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| Mary Jane England, MD |

| Washington Business Group on Health |

| David Fleming, MD |

| Center for Clinical Bioethics, Georgetown University |

| George Isham, MD |

| HealthPartners |

| Catherine Kunkle |

| National Business Coalition on Health |

| Beverly Malone, PhD, RN |

| American Nurses Association |

| Thomas Reardon, MD |

| American Medical Association |

| James Sabin, MD |

| Harvard Pilgrim Health Care |

| Paul Schyve, MD |

| Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization |

| Drew Smith, JD |

| American Association of Retired Persons |

| Myrl Weinberg |

| National Health Council |

Members of the E-Force Expert Advisory Panel on Privacy and Confidentiality

| (Organizational affiliation listed for identification purposes) |

| Frank Riddick, MD Chair |

| Alton Ochsner Medical Foundation |

| Linda L. Emanuel, MD, PhD |

| Northwestern Medical School |

| Paul Clayton, PhD |

| InterMountain Health Care |

| George Duncan, PhD |

| Carnegie Mellon University |

| Ellen Clayton, MD, JD |

| Vanderbilt University |

| Steven S. Coughlin, PhD, MPH |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Bob Gellman, JD |

| Privacy and Information Policy Consultant |

| Denise Nagel, MD |

| National Coalition for Patient Rights |

| Paul Schyve, MD |

| Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations |

| Linda Shelton |

| National Committee for Quality Assurance |

Ethical Force Program Staff

| Matthew K. Wynia, MD, MPH |

| Ethical Force Program, Executive Director |

| Deborah Cummins, PhD |

| Ethical Force Program, Associate Director |

| Benjamin Kim |

| Institute for Ethics Intern |

| Sheri Alpert, MA, MPA |

| Consultant to the Ethical Force Program on Privacy Issues |

REFERENCES

- 1.Emanuel L. Professional standards in health care: calling all parties to account. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997;16:52–4. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wynia M. Performance measures for ethics quality. Eff Clin Pract. 1999;2:294–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldman J. Protecting privacy to improve health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 1998;17:47–60. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.6.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Etzioni A. The Limits of Privacy. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gostin LO, Hadley J. Health services research: public benefits, personal privacy, and proprietary interests. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:833–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-10-199811150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gostin L. Health information privacy. Cornell Law Review. 1995;80:101–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For the Record: Protecting Electronic Health Information. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monane M, Mathias DM, Nagle BA, Kelly MA. Improving prescribing patterns for the elderly through an online drug utilization review intervention: a system linking the physician, pharmacist, and computer. JAMA. 1998;280:1249–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.14.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell A. Experts address concerns over plans invading medical confidentiality of members. BNA Healthcare Daily Report. 1998;volume 6(37) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Report of the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics. Washington, DC: National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics; 1997. Health Privacy and Confidentiality Recommendations. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marwick C. Medical records privacy: a patient rights issue. JAMA. 1996;276:1861–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Commerce Privacy Conference. Washington, DC: Department of Commerce; 1998. 1998 Harris-Westin Survey on Privacy and the Elements of Self-Regulation. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris-Equifax Consumer Privacy Survey, 20–29 July, 1996. 2000. Available at: http://www.equifax.com/consumer/parchive/svry96/survy96a.html Accessed March 20.

- 14.2000 Ethics Survey of Consumer Attitutdes about Health Web Sites. California Healthcare Foundation and the Internet Healthcare Coalition. 2000. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/press/viewpress.cfm?itemID=1015 Accessed March 20.

- 15.Buckovich SA, Rippen HE, Rozen MJ. Driving towards guiding principles: a goal for privacy, confidentiality and security of health information. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999;6:122–33. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1999.0060122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The State of Health Privacy: An Uneven Terrain. Washington, DC: Health Privacy Project; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Brien DG, Yasnoff WA. Privacy, confidentiality and security in information systems of state health agencies. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16:351–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westin A, Louis Harris and Associates . A Survey of the Public and Leaders. Equifax, Inc.; 1993. Health Care Information Privacy. Study no. 934009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American worry about the privacy of their computerized medical records; health plans, drug companies and government health programs are least trusted. BW Healthwire. 1999 January 29. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldman J, Hudson Z. Exposed: A Health Privacy Primer for Consumers. Washington, DC: Health Privacy Project, Institute for Health Care Research and Improvement, Georgetown University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alpert S. Smart cards, smarter policy. Medical records, privacy, and health care reforms. Hastings Cent Rep. 1993;23:13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Studdert D. Direct contracts, data sharing and employee risk selection: new stakes for patient privacy in tomorrow's health insurance markets. Am J Law Med. 1999;25:233–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Etzioni A. Medical records. Enhancing privacy, preserving the common good. Hastings Cent Rep. 1999;29:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore J. Confidentiality casualty: patient billing printouts released in Kansas fraud case. Crain Modern Health Care Magazine. 1998;28(37):3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Harrow R., Jr Survey not stifled by privacy concerns. Washington Post. 1998;C18 December 15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1993. Protecting Privacy in Computerized Medical Information. OTA-TCT-576. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncan G, Jabine T, Wolf VD. Committee on National Statistics, Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, National Research Council and the Social Science Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1993. Private Lives and Public Policies: Confidentiality and Accessibility of Government Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sweeney L. Weaving technology and policy together to maintain confidentiality. J Law Med Ethics. 1997;25:98–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1997.tb01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armstrong MP, Rushton G, Zimmerman DL. Geographically masking health data to preserve confidentiality. Stat Med. 1999;18:497–525. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990315)18:5<497::aid-sim45>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohrn A, Ohno-Machado L. Using Boolean reasoning to anonymize databases. Artif Intell Med. 1999;15:235–54. doi: 10.1016/s0933-3657(98)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gostin L, Hodge J. Balancing individual privacy and communal uses of health information. Model State Health Privacy Project. 2000 Available at: http://www.critpath.org/msphpa/docs.htm Accessed October 25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finkelstein K. The computer cure. The New Republic. 1998;219:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrows Rc, Jr, Clayton PD. Privacy, confidentiality, and electronic medical records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3:139–48. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1996.96236282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell SG, Gibby GL, Collingwood S. The Internet and electronic transmission of medical records. J Clin Monit. 1997;13:325–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1007404806312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duncan G, Pearson R. Enhancing access to microdata while protecting confidentiality: prospects for the future. Stat Sci. 1991;6:219–39. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsi KP, Winslade WJ, Corcoran K. Does confidentiality have a future? The computer-based patient record and managed mental health care. Trends Health Care Law Ethics. 1995;10:78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rind D, Szolovits P, Kohane I. Confidentiality and electronic medical records. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:510–1. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-6-199803150-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melton L. Privacy and medical records research. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1076–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coughlin S. Ethics in Epidemiology and Public Health Practice: Collected Works. Columbus, Ga: Quill Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCarthy DB, Shatin D, Drinkard CR, Kleinman JH, Gardener JS. Medical records and privacy: empirical effects of legislation. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:417–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chicago, Il: Blue Cross Blue Shield Association of America; 1999. Cost and Impact Analysis: Common Components of Confidentiality Legislation. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Statement for the Record on the Confidentiality of Health Information. Washington, DC: The Washington Business Group on Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pimley D. Maine experience shows potential snag as public grapples with patient privacy. BNA's Health Law Reporter. 1999;8(5) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vukadinovich DM, Coughlin SS. State confidentiality laws and restrictions on epidemiologic research: a case study of Louisiana Law and proposed solutions. Epidemiology. 1999;10:91–4. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199901000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hodge JG, Jr, Gostin LO, Jacobson PD. Legal issues concerning electronic health information: privacy, quality, and liability. JAMA. 1999;282:1466–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naser C, Alpert S. Protecting the Privacy of Medical Records: An Ethical Analysis. Boston, Mass: National Coalition for Patient Rights; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doyal L. Human need and the right of patients to privacy. J Contemp Health Law Policy. 1997;14:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kremer T, Gesten E. Confidentiality limits of managed care and clients' willingness to self-disclose. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1998;28:553–8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldman J, Muligan D. Privacy and health information systems: A guide to protecting patient confidentiality. Washington, DC: Center for Democracy and Technology; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winslade W. Privileged Communications. In: Reich W, editor. Encyclopedia of Bioethics. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster MacMillan; 1995. pp. 2073–6. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seigler M. Confidentiality in medicine - a decrepit concept. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1518–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212093072411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allen A. Privacy in Health Care. In: Reich W, editor. Encyclopedia of Bioethics. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster MacMillan; 1995. pp. 2064–73. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emanuel LL. A professional response to demands for accountability: practical recommendations regarding ethical aspects of patient care. Working Group on Accountability. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:240–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-2-199601150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Litwin M. How to Measure Survey Reliability and Validity. In: Fink A, editor. The Survey Kit. Vol 7. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aday L. Designing and Conducting Health Surveys: A Comprehensive Guide. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alpert S. Research Involving Human Biological Materials: Ethical Issues and Policy Guidance, Volume II, Commissioned Papers. Washington, DC: National Bioethics Advisory Commission; 1997. Privacy and the Analysis of Stored Tissues; pp. A1–A36. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chapman A. Developing Health Information Systems Consistent with Human Rights Criteria. In: Chapman A, editor. Health Care and Information Ethics: Protecting Fundamental Human Rights. Kansas City, Mo: Sheed & Ward; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ethical Issues and Patient Rights: Across the Continuum of Care. Oakbrook Terrace, Il: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Starr P. Health and the right to privacy. Am J Law Med. 1999;25:193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Records, Computers, and the Rights of Citizens: Report of the Advisory Committee on Automated Personal Data Systems. Washington, DC: United States' Secretary of Health Education and Welfare; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flaherty D. Protecting Privacy in Surveillance Societies. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Model Code for the Protection of Personal Information. Etobicoke, Ontario: National Standards Association of Canada; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guidelines for the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Data Flows of Personal Data. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janes G, Clutter G, Greenberg M. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act: new standards for health data systems. J Reg Mgmt. 1998. pp. 86–90.

- 65.Dahm L. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Health Law News. 1999;13:8, 15. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brittin A, Brown A, Tedesco J. Privacy: Understanding HHS's Proposed Health Information Privacy Standard. Washington, DC: McKenna and Cuneo, LLP; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Protecting Personal Health Information: A Framework for Meeting the Challenges in a Managed Care Environment. Washigton, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Accreditation 2000: Draft Standards for Managed Care Organizations and Managed Behavioral Healthcare Organizations. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Model State Health Privacy Project. Sponsored by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, the National Conference of State Legislatures, and the Georgetown University Law Center (GULC). 1999. 2000. Available at: http://www.critpath.org/msphpa/docs.htm Accessed October 25.

- 70.Best Principles for Health Privacy. Washington, DC: Health Privacy Project; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pomeroy G. NAIC News: message from the officers. September 1998. 2000. Available at: http://www.naic.org/1news/news/naicnews/september_1998_naic_news.htm Accessed October 25, 2000.

- 72.Interim Report of the Inter-Council Task Force on Privacy and Confidentiality - Board of Trustees Report 36-A-99. Chicago, Il: American Medical Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Final Report of the Inter-Council Task Force on Privacy and Confidentiality - Board of Trustees Report 16-I-99. Chicago. Il: American Medical Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Electronic Communications and Privacy Interest Group. American Bar Association; 1999. Available at: http://www.abanet.org/health/electronic/home.htmlaccessed 1/5/01. [Google Scholar]

- 75.AAHP's Board of Directors Adds New Protections to Industry-Wide, Patient-Centered Initiative. January 7, 1999. 2000. Available at: http://www.aahp.org Accessed October 25.

- 76.ASHG statement. Professional disclosure of familial genetic information. The American Society of Human Genetics Social Issues Subcommittee on Familial Disclosure. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:474–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.American College of Epidemiology. Statement on health data control, access, and confidentiality. 1999. Available at: http://acepidemiology.org/data.html. Accessed July 12.

- 78.Chilton L, Berger JE, Melinkovich P, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatric Practice Action Group and Task Force on Medical Informatics. Privacy protection and health information: patient rights and pediatrician responsibilities. Pediatrics. 1999;104:973–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bluml BM, Crooks GM. Designing solutions for securing patient privacy—meeting the demands of health care in the 21st century. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1999;39:402–7. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Information for Health: An Information Strategy for the Modern NHS 1998–2005. London England: British National Health Service; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Protecting Data Privacy in Health Services Research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine Committee on the Role of Institutional Review Boards in Health Services Research Data Privacy Protection; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Protecting the Confidentiality of Patient Information in a Rapidly Changing Health Care System. Washington, DC: Health Systems Research, Inc.; 1998. Protecting the Confidentiality of Patient Information in a Rapidly Changing Health Care System: Summary of a National Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. What is accountability in health care? Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:229–39. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-2-199601150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]