Abstract

The nucleus is a definitive feature of eukaryotic cells, comprising twin bilamellar membranes, the inner and outer nuclear membranes, which separate the nucleoplasmic and cytoplasmic compartments. Nuclear pores, complex macromolecular assemblies that connect the two membranes, mediate communication between these compartments. To explore the morphology, topology, and dynamics of nuclei within living plant cells, we have developed a novel method of confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy under time-lapse conditions. This is used for the examination of the transgenic expression in Arabidopsis thaliana of a chimeric protein, comprising the GFP (Green-Fluorescent Protein of Aequorea victoria) translationally fused to an effective nuclear localization signal (NLS) and to β-glucuronidase (GUS) from E. coli. This large protein is targeted to the nucleus and accumulates exclusively within the nucleoplasm. This article provides online access to movies that illustrate the remarkable and unusual properties displayed by the nuclei, including polymorphic shape changes and rapid, long-distance, intracellular movement. Movement is mediated by actin but not by tubulin; it therefore appears distinct from mechanisms of nuclear positioning and migration that have been reported for eukaryotes. The GFP-based assay is simple and of general applicability. It will be interesting to establish whether the novel type of dynamic behavior reported here, for higher plants, is observed in other eukaryotic organisms.

INTRODUCTION

A definitive feature of eukaryotic cells is the nucleus, first described in stamen cells of Tradescantia by Robert Brown in 1831, which is found in all cell types at some stage of their development. The nucleus comprises twin bilamellar membranes, the inner and outer nuclear membranes, which serve to separate the nuclear contents, the nucleoplasm, from the cytoplasm. Communication between these compartments is mediated by nuclear pores, complex macromolecular assemblies that connect the two membranes.

All of our information concerning nuclear morphology, topology, and dynamics comes from the use of various forms of microscopy. The major components of the nucleoplasm, including proteins, RNA, and DNA, do not absorb in the visible part of the spectrum. Thus, nuclei are nearly translucent and nonfluorescent. This impedes the observation of nuclei within living cells with standard bright-field or fluorescence microscopy. Although other forms of light microscopy can be used to examine nuclei, particularly phase contrast and differential interference contrast microscopy, which rely on optical properties other than absorbance and fluorescence, this is practical only in nonpigmented cells and in tissues having simple three-dimensional organization.

We have developed an alternative method for observation of nuclei in living plant cells that uses confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy (Chytilova et al., 1999). Based on the transgenic expression of the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) of Aequorea victoria, it involves biosynthesis of a chimeric protein, comprising a codon-optimized GFP coding sequence translationally fused to an effective nuclear localization signal (NLS) and to the complete coding region of β-glucuronidase (GUS) from Escherichia coli (Grebenok et al., 1997a,b). This large (>100 kDa) protein is targeted to the nucleus and accumulates exclusively within the nucleoplasm, where it can be conveniently observed with confocal microscopy.

NLS-GFP-GUS is expressed and targeted to the nuclei of dicots (tobacco and Arabidopsis; Grebenok et al., 1997a,b; Chytilova et al., 1999), monocots (onion epidermal cells; D. Collings, personal communication), and lower plants (Physcomitrella patens; K. Schumaker, personal communication). The level of biosynthesis and nuclear accumulation of the chimeric GFP molecule is sufficient so that observation of the living plant tissues with the confocal microscope can be done without excessive illumination, which can lead to photodamage. Furthermore, the excitation and emission properties of GFP are sufficiently different from those of other cellular fluorophores that fluorescence emission from the nuclei can be readily recognized, even in highly pigmented cells within organized tissues (such as leaves, stems, and floral organs). Together, these factors make it possible to examine the tissues of transgenic plants under time-lapse conditions, thereby obtaining information about nuclear dynamics.

In this report, we provide on-line access to these data in the form of a series of QuickTime files. Our experiments indicate that the nuclei display remarkable and unusual properties, including polymorphic shape changes and rapid intracellular movement over long distances. This movement is mediated by actin but not by tubulin; therefore, it appears distinct from established mechanisms of nuclear positioning and migration (Reinsch and Gönczy, 1998; Morris, 2000). Given the simple nature of the GFP-based assay and its general applicability, it will be of interest to examine how general within eukaryotes is the occurrence of this novel type of dynamic behavior.

VIDEO MOVIES

Movies were produced from confocal stacks collected with the use of a Bio-Rad (Richmond, CA) 1024 confocal microscope (Grebenok et al., 1997a,b). Bio-Rad PIC files were processed and converted to AVI format movies with the use of the program Confocal Assistant. These were resized, compressed, and converted to QuickTime movies with the use of Adobe (Mountain View, CA) Premier. We acknowledge the assistance of Jeff Imig (University of Arizona Faculty Center for Instructional Innovation) in producing the QuickTime movies.

Movie 1/Figure 1: Root Hair Development in Arabidopsis thaliana (Movie01.mov)

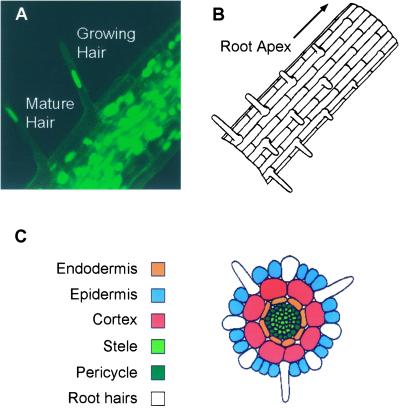

Figure 1.

Movie 1. (A) Nuclear movement associated with root hair development in primary roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Bar, 30 μm. The movie was created from 60 images collected at 3-min intervals. (B) Longitudinal representation of a primary root of A. thaliana, illustrating the developmental changes at the epidermal surface during root hair elongation. (C) Cross-sectional representation of a primary root of A. thaliana, illustrating the different cell types and their relationship to root hair elongation. (Panels B and C were redrawn from Schiefelbein et al. [1997] with permission of the authors).

Observation of the developing root of Arabidopsis thaliana L. is particularly convenient with the laser scanning confocal microscope, because these roots display little or no autofluorescence when illuminated at 488 nm (which is near the optimal excitation wavelength for S65T GFP; Tsien, 1998). Seeds are sown onto agar medium contained in a LabTek one-chamber chambered coverglass (Nunc, Nalgene, NY). After germination, the primary roots grow downward until they encounter the No. 1 borosilicate coverglass that constitutes the base of the chamber, through which they can be observed. Hairs develop in a position-dependent manner on a subset of the epidermal cells of primary roots, and this represents an established model system for the study of cell differentiation (Figure 1) (Schiefelbein et al., 1997; Schneider et al., 1997, 1998). Movie 1 consists of images taken from a primary root over the time course of the initial development of an individual root hair. Confocal images were acquired at 1-min intervals. Expansion of an initial site of swelling of the epidermal cell results in production of the root hair. During this time, a large amount of cytoplasmic activity is evident at the growing tip of the hair. There is also considerable movement of the individual nuclei, both within the body of the root and within the root hair. After the root hair has expanded beyond a certain point, the nucleus enters the shaft of the hair. Changes in nuclear shape are apparent during this process, the root hair nucleus being quite flexible, whereas most of the nuclei within the body of the primary root remain spheroidal.

Movie 2/Figure 2: Long-Distance Rapid Movement of Nuclei within Fully Developed Root Hairs (Movie02.mov)

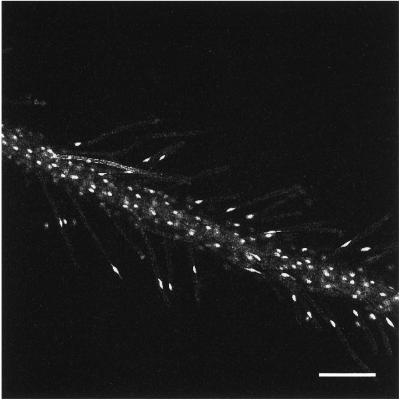

Figure 2.

Movie 2. Nuclear dynamics within the cells of a mature (nonexpanding) root and its associated hairs. Bar, 180 μm. The movie was created from 360 images collected at 1-min intervals.

The second movie was produced from a time-course examination of a mature primary root, which possesses fully expanded root hairs. Images were acquired at 1-min intervals for 180 min. Most of the nuclei within the frame are actively moving. The velocity of nuclear movement is variable. It is 0.3–2.0 μm/min within cortical cells of the root body and within the body of the root hair extending away from the root. Movement is more rapid (4–5 μm/min) within the portion of the root hair cell attached to the body of the root. Movement is bidirectional and does not appear to be coordinated between hairs. Whereas the majority of the nuclei within the body of the root are spheroidal, those in the root hairs frequently are elongated along the major axis of the hair. Within the root hairs, spheroidal nuclei move more slowly (0.3–0.5 μm/min) than those that are elongated (1–2 μm/min). For seedlings growing for extended periods of time (>14 d) on agar medium, thread-like processes were observed parallel to the axis of movement.

Movie 3/Figure 3: Examination of Nuclear Dynamics within Individual Root Hairs (Movie03.mov)

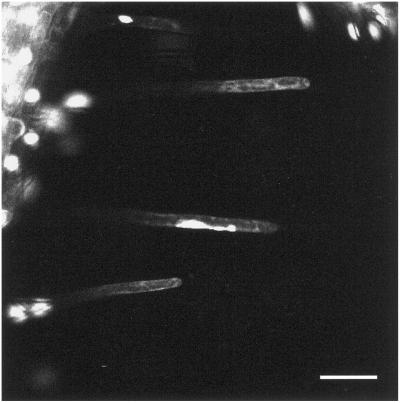

Figure 3.

Movie 3. Examination of nuclear dynamics within individual root hairs; movement is accompanied by gross alterations in nuclear shape. Bar, 50 μm. The movie was created from 230 images collected at 1-min intervals.

At higher magnification, the dynamic behavior of the nuclei within the root hairs is revealed at greater spatial resolution. In this movie, three root hairs are visible, within which the nuclei are in continuous motion. A further feature in all cases is the pleiomorphic character of the nuclei. The nuclei do not remain as spheroids but divide into multiple subnuclear structures, of dissimilar sizes, that remain connected by thread-like processes. Within the lowest of the three hairs, the subnuclear structures, at different times, move both in the same and in opposing directions. In some of the root hairs, the division process appears reversible, and aggregation of the subnuclear structures can be observed (see also Movie 4/Figure 4).

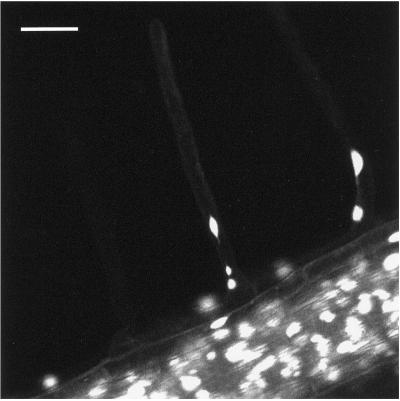

Figure 4.

Movie 4. Aggregation of subnuclear structures within root hairs. Bar, 35 μm. The movie was created from 200 images collected at 1-min intervals.

Movie 4/Figure 4: Aggregation of Subnuclear Structures within Root Hairs (Movie04.mov)

In this movie, the root hair at the center of the screen initially contains three subnuclear structures, each of a different size and all interconnected by thread-like processes. Considerable biosynthetic flux is observed within the body of the hair, presumably highlighted by GFP newly synthesized on cytoplasmic ribosomes. Movement of the nuclei does not appear correlated with gross movements of the cytoplasm. By the end of the movie, the three subnuclear structures have aggregated into a single nucleus. These observations imply that subdivision of nuclei within root hairs can be reversible.

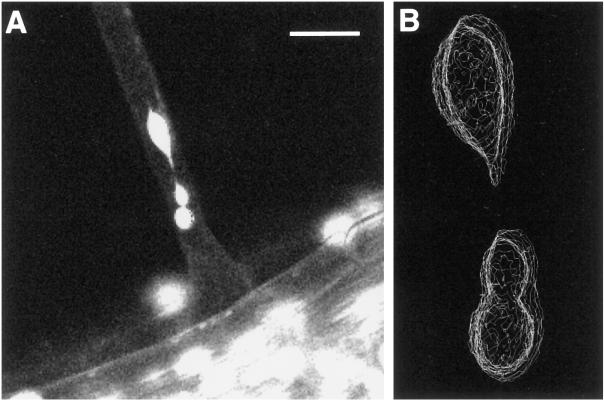

Movie 5/Figure 5: Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of Subnuclear Structures (Movie05.mov)

Figure 5.

Movie 5. Z-series analysis of subnuclear structures; these structures are physically distinct. Bar, 35 μm. The three-dimensional reconstruction in B was assembled from the corresponding confocal Z-stack with the use of Data Explorer running on an SGI Onyx2 workstation. The contour wire-frame images were created with the use of a two-dimensional contour algorithm to identify the nuclear peripheries on each slice of the stack, then composited together into a three-dimensional stack of contours. We acknowledge the assistance of Marvin Landis (University of Arizona Center for Computing and Information Technology) in producing the reconstruction.

Given that confocal images can represent very thin optical sections, it is possible that the apparently separate subnuclear structures visualized in previous movies might be derived from the imaging of a single nucleus that remains topologically connected out of the confocal plane. To address this issue, we analyzed the nuclei within a single root hair in the form of a Z-dimensional stack of images. Twenty image planes were accumulated, spaced at 0.5-μm intervals along the Z-axis. Movie 5 provides several passes through this stack, and a three-dimensional reconstruction is presented in Figure 5B. The subnuclei do not represent a single, reticulate nucleus. Instead, they are separate structures, being connected within the plane of the median optical section by thin fibers (Figure 5A), which were smaller than the limits imposed by the reconstruction.

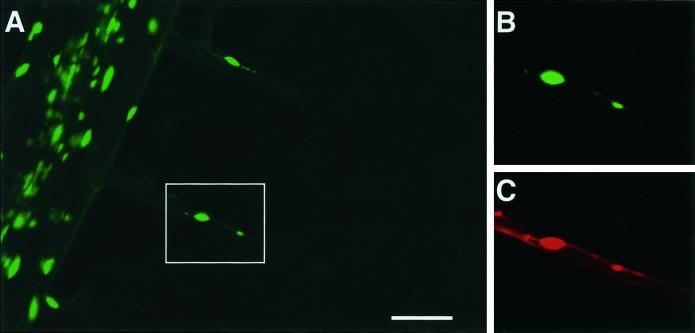

Figure 6: The Subnuclear Structures Contain DNA

Figure 6.

Subnuclear structures contain DNA. (A) Both root hairs can be seen to contain nuclei as well as subnuclear structures. (B) An enlargement of the boxed area in A. (C) The same area after ethanol fixation of the tissue followed by staining with propidium iodide. Bar, 50 μm.

The conclusions regarding the occurrence and dynamic behavior of nuclei and subnuclear structures within root hairs rely on the assumption that GFP accumulation solely identifies the nucleus and that GFP import into the nucleus is mediated by nuclear pores. In theory, GFP accumulation could identify not only the nucleus but also another, nonnuclear, subcellular compartment. To determine whether subnuclear structures identified through GFP targeting contained DNA, we examined living root hairs by confocal microscopy as described previously. Root hairs containing subnuclear structures (Figure 6, A and B) were then fixed with the use of 80% ethanol and stained with propidium iodide (Figure 6C). Ethanol fixation has the effect of eliminating GFP fluorescence and permeabilizing the plasma membrane to propidium iodide. The nuclei and subnuclear structures were both fluorescent after staining with propidium iodide, and the fluorescence intensities appeared qualitatively similar. This fluorescence was not affected by treatment of the fixed cells with ribonuclease but was eliminated by deoxyribonuclease (our unpublished results). These results confirm that the subnuclear structures contain DNA.

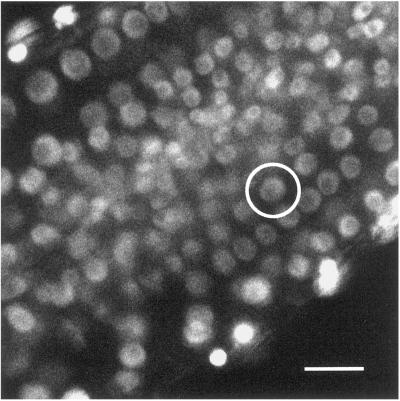

Movie 6/Figure 7: Analysis of Nuclear GFP Dynamics as a Function of the Cell Division Cycle (Movie06.mov)

Figure 7.

Movie 6. Analysis of nuclear GFP dynamics as a function of the cell division cycle. In Movie 6, the circled nucleus enters into prometaphase, at which point nucleoplasmic GFP disperses into the cytoplasm. Subsequent cell division is followed by reestablishment of an intact nuclear membrane within the daughter cells. GFP fluorescence then accumulates within the nuclei. Bar, 15 μm. The movie was created from 90 images collected at 1-min intervals.

Further confirmation of the validity of the use of GFP accumulation as a marker of the nucleus was obtained by examination of the behavior of the GFP-accumulating compartment as a function of the cell division cycle. Movie 6, which shows the primary root at 1-min intervals for a period of 40 min, contains several examples of nuclei undergoing mitosis. The most obvious of these is circled in Figure 7. On entry into prometaphase, the nuclear membranes disperse and nuclear GFP fluorescence spreads throughout the cytoplasm. After mitosis and cytokinesis, the production of a new cell wall separates the daughter cells. GFP is then reimported into the daughter nuclei.

The results displayed in this movie are consistent with GFP-derived fluorescence highlighting only the nucleus. This suggests that the fluorescent objects observed in the root hair cells represent subnuclear structures, rather than a nonnuclear compartment, and that these structures contain functional nuclear pores.

Given that root hairs play a crucial role in nutrient assimilation and water uptake, these observations imply that both the movement and the pleiomorphic shapes of the nuclei have functional significance. Because the hair cells are nondividing and have a highly anisotropic shape, it is possible that the changes in nuclear position facilitate the distribution of macromolecules, such as mRNA, to appropriate parts of the cell. Tip-tracking movements of the vegetative nucleus and generative cell have been described in pollen tubes (Heslop-Harrison and Heslop-Harrison, 1989). In other eukaryotes, nuclear movement is associated primarily with cell division or with a phenomenon termed nuclear migration or nuclear positioning (Reinsch and Gönczy, 1998; Morris, 2000), typified by mating and cell division in yeast (Shaw et al., 1997; Yamamoto et al., 1999), hyphal tip-associated growth in filamentous fungi (Morris, 2000), early embryogenesis and eye differentiation in Drosophila (Foe and Alberts, 1983; Baker et al., 1993), and development in Caenorhabditis elegans (Morris, 2000). Nuclear positioning has also been described in legume root hairs (Lloyd et al., 1987), Micrasterias (Meindl et al., 1994), and Spirogyra (Grolig, 1998) and during fertilization in Pelvetia (Swope and Kropf, 1993). Other cases of nuclear positioning have been reported within the syncytial embryo (von Dassow and Schubiger, 1994) and nurse cells (Guild et al., 1997) of Drosophila.

Another form of nuclear movement, termed nucleokinesis (Morris et al., 1998), is recognized as a general form of microtubule-based cell migration. It is driven by movement of the nucleus through a long anterior process previously extended from the cell body and has been described as underlying the movement of adenocarcinoma cells, cultured neurons, and blastomeres of C. elegans; nucleokinesis is also possibly defective in lissencephaly (Morris et al., 1998; Morris, 2000). Finally, in some specialized animal cells, such as Schwann cells (Bunge et al., 1989), as well as in interphase cells of Dictyostelium (Koonce et al., 1999) and multinucleate cells of Nitella (Allen and Allen, 1978), various uncategorized forms of nuclear movement, such as rotations and circumnavigation around the cellular periphery, have been described. In the case of muscle fibers, nuclei are observed to translocate throughout the length of the myotubes (Englander and Rubin, 1987).

In terms of the gross changes in nuclear morphology observed in the root hairs, these might represent means whereby different chromosomal regions could contribute appropriately to the metabolic and developmental activities of the cell. Persistently anisotropic distributions of telomeres and centromeres have been described in interphase nuclei (Abranches et al., 1998; Dong and Jiang, 1998; reviewed by Franklin and Cande, 1999). This may be a consequence of constraints on chromosomal diffusion within the nuclei or of specific interactions of different chromosomal structures with the nuclear membrane (Franklin and Cande, 1999) and is presumably related to nuclear function.

In terms of the observed dynamic changes in nuclear shape, of particular interest is the situation found in ciliates, which contain two different nuclei (the micronucleus and the macronucleus) within a common cytoplasm (for review, see Raikov, 1996). Whereas micronuclei are small and compact and divide mitotically, macronuclei are variable in both size and shape. Division of the macronucleus is amitotic and involves neither chromosome condensation nor a conventional microtubular spindle. Instead, division occurs by a stretching and pinching process that can be asymmetric, giving rise to macronuclear buds. Interestingly, these buds can regenerate to the size of the parental macronucleus, which is possible only due to the ampliploid nature of the macronucleus (Raikov, 1996). Further intriguing parallels with the situation in root hairs concern the segregation of macronuclei during cytokinesis, which involves nuclear movement rather than nuclear division, and the fact that root hair nuclei most probably are endoreduplicated.

Finally, the existence of mechanical interactions linking the extracellular matrix, cellular shape, and nuclear form has been demonstrated empirically in endothelial cells by micromanipulation of cell surface receptors (Maniotis et al., 1997), and it has been postulated that such changes in nuclear shape might influence gene expression (Chicurel et al., 1998). Therefore, it is possible that the alterations in nuclear shape observed in root hairs might also contribute directly to the regulation of gene expression.

INVOLVEMENT OF MICROFILAMENTS AND NOT MICROTUBULES IN ROOT NUCLEAR DYNAMICS

In the next set of experiments, we explored the effects of a variety of chemical treatments on root nuclear dynamics and on the localization of GFP fluorescence within the nuclei to determine what cellular mechanisms might be responsible for these phenomena. For these experiments, the seeds were sown on the surface of 2 ml of agar-solidified medium contained in LabTek one-chamber chambered coverglass. The coverglass was oriented vertically so that the roots grew downward on the agar surface. Treatments involved the addition of 2 ml of a solution of the specific drug or biochemical to 4- to 6-d-old seedlings. After the treatment period (Table 1), the plantlets were gently rinsed with distilled water and the roots were examined under the confocal microscope. Images were recorded at 1.5-min intervals for 1 h.

Table 1.

Effects of drugs on the movement of the root nuclei and nucleoplasmic GFP accumulation

| Drug | Concentration (μM) | Time (h) | Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxol | 10 | 1 | NEa |

| 10 | 6 | NE | |

| 20 | 6 | NE | |

| 20 | 24 | NE | |

| Oryzalin | 10 | 1 | NE |

| 10 | 4 | NE | |

| 20 | 4 | NE | |

| 20 | 16 | NE | |

| 50 | 4 | NE | |

| 100 | 4 | GFP lost from the nucleoplasm | |

| Vinblastine | 5 | 3 | NE |

| 5 | 24 | NE | |

| 20 | 1 | NE | |

| 100 | 1 | NE | |

| 500 | 1 | Slight decrease in the velocity of some of the nuclei | |

| Colchicine | 10,000 | 65 | NE |

| 50,000 | 4 | NE | |

| Latrunculin B | 10 | 5 min | Movement stopped 15 min after completion of the treatment |

| 10 | 15 min | Movement stopped | |

| Cytochalasin D | 50 | 1 | NE |

| 50 | 4 | NE | |

| 50 | 16 | Velocity decreased | |

| 100 | 4 | NE | |

| 100 | 16 | Movement stopped in >90% of the nuclei | |

| Cytochalasin B | 50 | 1 | NE |

| 50 | 5 | NE | |

| 100 | 4 | Movement stopped | |

| N-Ethylmaleimide | 50 | 1 | Movement stopped in the root hairs; some movement in the root body |

| 100 | 1 | Movement stopped | |

| 10,000 | 2 | GFP lost from the nucleoplasm |

NE, no effect. Nuclei continued movement, and GFP was retained within the nucleoplasm.

In our experiments, the addition of taxol, oryzalin, vinblastine, or colchicine, which influence tubulin polymerization (Bershadsky and Vasiliev, 1988; Morejohn, 1991; Kuss-Wymer and Cyr, 1992; Rai and Wolff, 1996; Smith and Raikhel, 1998), had no effect on the shape or movement of the root nuclei (Table 1). In contrast, treatment of the roots with latrunculin B (10 μM) completely abolished nuclear movement within 15 min, as did treatment for 4 h with 100 μM cytochalasin B or for 15 h with 100 μM cytochalasin D (in the latter case, not all of the nuclei ceased movement; Table 1). Under these conditions, the drugs are known to decrease the overall amounts of polymerized actin within the cell (Bershadsky and Vasiliev, 1988; Ayscough et al., 1997; Smith and Raikhel, 1998; Gibbon et al., 1999). The lower effectiveness of cytochalasin D in our hands supports the suggestion (Gibbon et al. 1999) that it inhibits the polymerization of new actin filaments, rather than activating the depolymerization of existing filaments.

Treatment with N-ethylmaleimide for 1 h completely inhibited nuclear movement. Although N-ethylmaleimide is a general nucleophilic reagent, it has been shown to react specifically with actin in vivo, forming “rigor complexes” (Bershadsky and Vasiliev, 1998) and thereby preventing myosin attachment. This is consistent with the involvement of myosin in nuclear movement. It is not possible from these results to determine whether the nuclei interact directly with actin microfilaments or are passively propelled by bulk cytoplasmic streaming, because cytoplasmic streaming is also interdicted by the same drugs that either act to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton or affect the interactions of myosin and actin (Allen and Allen, 1978; McCurdy and Williamson, 1991; Meagher et al., 1999). The elongated appearance of the nuclei and the observations of strand-like connections between subnuclear components favor the former possibility, as does the observation of no clear correlation between patterns of cytoplasmic streaming (compare Movies 1, 3, and 4) and overall nuclear movement. It was not possible to configure the confocal microscope for the simultaneous examination of cytoplasmic streaming with the use of either phase contrast or Nomarski illumination.

Within root hairs, the lack of involvement of microtubules in nuclear movement generally distinguishes this phenomenon from that of most cases of nuclear migration, nuclear positioning, and nucleokinesis (Foe and Alberts, 1983; Lloyd et al., 1987; Baker et al., 1993; Swope and Kropf, 1993; Meindl et al., 1994; Shaw et al., 1997; Grolig, 1998; Reinsch and Gönczy, 1998; Yamamoto et al., 1999; Morris, 2000). The situation in Drosophila may be different, with nuclear positioning in nurse cells and the syncytial embryo being reported to be exclusively actin associated (von Dassow and Schubiger, 1994; Guild et al., 1997). In one case in plants, i.e., tip-tracking within pollen (Heslop-Harrison and Heslop-Harrison, 1989), movement was found to be driven by the interaction of actin with myosin associated with the surfaces of the vegetative nucleus and generative cell.

The implication of actin filaments mediating intracellular nuclear movement is of particular interest given the known involvement of actin and actin-binding proteins in the regulation of plant cell shape (Heslop-Harrison et al., 1986; McCurdy and Williamson, 1991; Staiger et al., 1997; Szymanski et al., 1999). A variety of plant cell systems exhibiting various forms of polar growth have provided useful information, including stomatal development (Cho and Wick, 1990, 1991), pollen germination (Picton and Steer, 1981; Heslop-Harrison et al., 1986; Lancelle et al., 1987; Miller et al., 1996; Kost et al., 1998), and trichome development (Szymanski et al., 1999). In all cases, the presence of actin-destabilizing drugs, such as the cytochalasins, adversely affects these polar processes. For example, prolonged cytochalasin D treatment severely disrupts trichome morphogenesis (Szymanski et al., 1999) through alteration of the coordination of stalk and branch growth and branch initiation. It remains unclear how actin destabilization disrupts polar growth, and for all of these systems it will be of interest to examine the role of nuclear movement during polar growth. Use of the NLS-GFP-GUS construct in transgenic plants should greatly facilitate this work.

CONCLUSION

Transgenic expression and targeting of the composite NLS-GFP-GUS protein provides a simple and sensitive means to examine nuclear dynamics in living plant cells. As far as we can tell from examination of the developmental and cellular biology of these plants, expression of this protein does not adversely affect cellular processes, nor does observation of the fluorescent nuclei with confocal microscopy, even for prolonged periods of time.

Targeting of the NLS-GFP-GUS protein provides insight into expected cellular processes, e.g., those concerning the dynamics of nuclear import during the process of mitosis and cell division (Movie 6); this type of movie should prove particularly effective as a teaching tool. It should be noted that the general experimental approach, combining nuclear targeting and confocal time-lapse imaging, should be applicable to eukaryotic organisms in general and should provide much useful information concerning nuclear dynamics and cellular polymorphisms.

NLS-GFP-GUS targeting also revealed unexpected phenomena, including the rapid and, in some cases, long-distance intracellular movement of nuclei, the adoption of nonspherical shapes by the nuclei (particularly those undergoing rapid translocation), and the reversible production of subnuclear structures within fully expanded cells. Our results also indicate that nuclear movement is mediated by actin and not by tubulins. Additional experiments are under way to examine the energy dependence and ionic requirements of nuclear movement and to determine the correlation, if any, between nuclear positioning and morphogenesis during development.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grants to D.W.G. from the National Science Foundation and from the U.S. Department of Agriculture under the National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program. Purchase of the confocal microscope was made possible by a grant to D.W.G. from the U.S. Department of Energy. The confocal stack resulting in Movie 2 was acquired with the assistance of Kathy Spencer in the laboratory of Dr. Marty Friedlander (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA)

Footnotes

Online version of this article contains video material for figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7. Online version is available at www.molbiolcell.org.

REFERENCES

- Abranches R, Beven AF, Aragon-Alcaide L, Shaw P. Transcription sites are not correlated with chromosome territories in wheat nuclei. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:5–12. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NS, Allen RD. Cytoplasmic streaming in green plants. Annu Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1978;7:497–526. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.07.060178.002433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayscough KR, Stryker J, Pokala N, Sanders M, Crews P, Drubin DG. High rates of actin filament turnover in budding yeast and roles for actin in establishment and maintenance of cell polarity revealed using the actin inhibitor latrunculin-A. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:399–416. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J, Theurkauf WE, Schubiger G. Dynamic changes in microtubule configuration correlate with nuclear migration in the preblastoderm Drosophila embryo. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:113–121. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bershadsky AD, Vasiliev IM. Cytoskeleton. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bunge RP, Bunge MB, Bates M. Movements of the Schwann cell nucleus implicate progression of the inner (axon-related) Schwann cell process during myelination. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:273–284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicurel ME, Chen CS, Ingber DE. Cellular control lies in the balance of forces. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:232–239. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S-O, Wick SM. Distribution and function of actin in the developing stomatal complex of winter rye (Secale cereale cv. Puma) Protoplasma. 1990;157:154–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S-O, Wick SM. Actin in the developing stomatal complex of winter rye: a comparison of actin antibodies and rh-phalloidin labeling of control and CB-treated tissues. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1991;19:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chytilova E, Macas J, Galbraith DW. Green Fluorescent. Protein targeted to the nucleus, a transgenic phenotype useful for studies in plant biology. Ann Bot. 1999;83:645–654. [Google Scholar]

- Dong F, Jiang J. Non-Rabl patterns of centromere and telomere distribution in the interphase nuclei of plant cells. Chromosome Res. 1998;6:551–558. doi: 10.1023/a:1009280425125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander LL, Rubin LL. Acetylcholine receptor clustering and nuclear movement in muscle fibers in culture. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:87–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foe VE, Alberts BM. Studies of nuclear and cytoplasmic behavior during the five mitotic cycles that precede gastrulation in Drosophila embryogenesis. J Cell Sci. 1983;61:31–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.61.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AE, Cande WZ. Nuclear organization and chromosome segregation. Plant Cell. 1999;11:523–534. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon BC, Kovar DR, Staiger CJ. Latrunculin B has different effects on pollen germination and tube growth. Plant Cell. 1999;11:2349–2363. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.12.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebenok RJ, Lambert GM, Galbraith DW. Characterization of the targeted nuclear accumulation of GFP within the cells of transgenic plants. Plant J. 1997a;12:685–696. [Google Scholar]

- Grebenok RJ, Pierson EA, Lambert GM, Gong F-C, Afonso CL, Haldeman-Cahill R, Carrington JC, Galbraith DW. Green Fluorescent. Protein fusions for efficient characterization of nuclear localization signals. Plant J. 1997b;11:573–586. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11030573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolig F. Nuclear centering in Spirogyra: force integration by microfilaments along microtubules. Planta. 1998;204:54–63. doi: 10.1007/s004250050229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guild GM, Connelly PS, Show MK, Tilney LG. Actin filament cables in Drosophila nurse cells are composed of modules that slide passively past one another during clumping. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:783–797. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.4.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison J, Heslop-Harrison Y. Myosin associated with the surface of organelles, vegetative nuclei and generative cells in angiosperm pollen grains and tubes. J Cell Sci. 1989;94:319–325. [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison J, Heslop-Harrison Y, Cresti M, Tiezzi A, Ciampolini F. Actin during pollen tube germination. J Cell Sci. 1986;86:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Koonce MP, Kohler J, Neujahr R, Schwartz JM, Tikhonenko I, Gerisch G. Dynein motor regulation stabilizes interphase microtubule arrays and determines centrosome position. EMBO J. 1999;18:6786–6792. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost B, Spielhofer P, Chua N-H. A GFP-mouse talin fusion protein labels plant actin filaments in vivo and visualizes the actin cytoskeleton in growing pollen tubes. Plant J. 1998;16:393–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss-Wymer CL, Cyr RJ. Tobacco protoplasts differentiate into elongate cells without net microtubule depolymerization. Protoplasma. 1992;168:64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lancelle SA, Cresti M, Hepler PK. Ultrastructure of the cytoskeleton in freeze-substituted pollen tubes of Nicotiana alata. Protoplasma. 1987;140:141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd CW, Pearce KJ, Rawlins KJ, Ridge RW, Shaw PJ. Endoplasmic microtubules connect the advancing nucleus to the tip of legume root hairs, but F-actin is involved in basipetal migration. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1987;8:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Maniotis AJ, Chen CS, Ingber DE. Demonstration of mechanical connections between integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, and nucleoplasm that stabilize nuclear structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:849–854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy DW, Williamson RE. Actin and actin-associated proteins. In: Lloyd CW, editor. The Cytoskeletal Basis of Plant Growth and Form. New York: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Meagher RB, McKinney EC, Kandasamy MK. Isovariant dynamics expand and buffer the responses of complex systems: the diverse plant actin gene family. Plant Cell. 1999;11:995–1005. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.6.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meindl U, Zhang D, Hepler PK. Actin microfilaments are associated with the migrating nucleus and the cell cortex in the green alga Micrasterias. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:1929–1934. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.7.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DD, Lancelle SA, Hepler PK. Actin microfilaments do not form a dense meshwork in Lilium longiflorum pollen tubes. Protoplasma. 1996;195:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Morejohn LC. The molecular pharmacology of plant tubulin and microtubules. In: Lloyd CW, editor. The Cytoskeletal Basis of Plant Growth and Form. New York: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Morris NR. Nuclear migration: from fungi to the mammalian brain. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1097–1101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris NR, Efimov VP, Xiang X. Nuclear migration, nucleokinesis and lissencephaly. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:467–470. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton JM, Steer MW. Determination of secretory vesicle production rates by dictyosomes in pollen tubes of Tradescantia using cytochalasin D. J Cell Sci. 1981;49:261–272. doi: 10.1242/jcs.49.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai SS, Wolff J. Localization of the vinblastine-binding site on β-tubulin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14707–14711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikov IB. Nuclei of ciliates. In: Hausmann K, Bradbury PC, editors. Ciliates: Cells as Organisms. Stuttgart, Germany: Gustav Fischer; 1996. pp. 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Reinsch S, Gönczy P. Mechanisms of nuclear positioning. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2283–2295. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.16.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefelbein JW, Masucci JD, Wong H. Building a root: the control of patterning and morphogenesis during root development. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1089–1098. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider K, Mathur J, Boudonck K, Wells B, Dolan L, Roberts K. The ROOT HAIRLESS 1 gene encodes a nuclear protein required for root hair initiation in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2013–2021. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider K, Wells B, Dolan L, Roberts K. Structural and genetic analysis of epidermal cell differentiation in Arabidopsis primary roots. Development. 1997;124:1789–1798. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.9.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SL, Yeh E, Maddox P, Salmon ED, Bloom K. Astral microtubule dynamics in yeast: a microtubule-based searching mechanism for spindle orientation and nuclear migration into the bud. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:985–994. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HMS, Raikhel NV. Nuclear localization signal receptor importin α associates with the cytoskeleton. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1791–1799. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.11.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger CJ, Gibbon BC, Kovar DR, Zonia LE. Profilin and actin-depolymerizing factor: modulators of actin organization in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Swope RE, Kropf DL. Pronuclear positioning and migration during fertilization in Pelvetia. Dev Biol. 1993;157:269–276. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DB, Marks MD, Wick SM. Organized F-actin is essential for normal trichome morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1999;11:2331–2347. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.12.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien R. The Green Fluorescent Protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Dassow G, Schubiger G. How an actin network might cause fountain streaming and nuclear migration in the syncytial Drosophila embryo. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1637–1653. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, West RR, McIntosh JR, Hiraoka Y. A cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain is required for oscillatory nuclear movement of meiotic prophase and efficient meiotic recombination in fission yeast. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1233–1249. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.6.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.