Abstract

When patients lack sufficient health care insurance, financial matters become integrally intertwined with biomedical considerations in the process of clinical decision making. With a growing medically indigent population, clinicians may be compelled to bend billing or reimbursement rules, lower standards, or turn patients away when they cannot afford the costs of care. This article focuses on 3 types of dilemmas that clinicians face when patients cannot pay for needed medical services: (1) whether to refer the individual to a safety net provider, such as a public clinic; (2) whether to forgo indicated tests and therapies because of cost; and (3) whether to reduce fees by fee waivers or other adjustments in billing. Clinicians' responses to these dilemmas impact on quality of care, continuity, safety net providers, and the liability risk of committing billing violations or offering nonstandard care. Caring for the underinsured in the current health care climate requires an understanding of billing regulations, a commitment to informed consent, and a beneficent approach to finding individualized solutions to each patient care/financial dilemma. To effect change, however, physicians must address issues of social justice outside of the office through political and social activism.

Keywords: access to care, indigent, clinical decision making, underinsured, uninsured

With nearly 44 million uninsured and an increasingly prevalent underinsured population in the United States, many physicians are confronted with patients who cannot pay for health care they need.1 While safety net institutions exist where patients can receive heavily subsidized or free medical services, most patients who are medically indigent find themselves at clinics and hospitals that bill for the services they provide.2 As a result, for many physicians, there are frequent encounters with patients who are concerned about the financial implications of the care they receive. This article examines the legal and ethical implications of incorporating the financial needs and concerns of patients into clinical decision making and the physician-patient relationship.

When an individual patient refuses needed care exclusively because of concerns about cost, the physician is confronted with a series of dilemmas that directly affect the physician-patient relationship. When a patient says, “I can't afford that,” what is a physician to do? Urge the patient to proceed despite the expense? Compromise the standard of care to reduce costs? Decline to provide substandard care, and therefore any care at all? Attempt to manipulate reimbursement rules or falsely underbill for the patient's benefit? These issues may be ongoing, since patient concerns about cost are likely to resurface at costly junctures in the care plan.

A process of negotiation may ensue in which the physician attempts to justify the needed services and the patient pushes for alternative approaches that cost less. At stake for the clinician are concerns about lowering the standard of care, exposure to liability, and professional insecurity about straying from well-trodden clinical care pathways that are generally recommended. For the patient, the stakes are concerns about financial and physical well-being.

The following case is provided as an illustration of the dilemmas a clinician confronts when a patient cannot afford the standard of care. Patient identifiers have been altered to assure anonymity.

Ms. Anna Wade is a self-employed seamstress with no health insurance. She is a 54- year-old woman who has been in good health, has never smoked, and exercises 3 times a week. In September 1999, she began experiencing episodes of chest pain that occurred mostly after meals and in the evenings before going to bed. Occasionally, the episodes occurred when she was exercising on a stationary bicycle in her apartment building. Initially, she ignored the symptoms, but began to worry as they worsened over time. She noticed a loss of appetite, and her trousers became loose. One afternoon, she took the bus with her sister to a nearby hospital to be seen in the walk-in clinic. At the desk, she made a $38 prepayment that was required because of her status as uninsured.

The physician listened to her story and performed a physical exam. He said that he thought her symptoms were caused by “heartburn,” which he explained has nothing to do with the heart, but is caused when acid in the stomach regurgitates up into the esophagus, causing pain. However, he also emphasized 2 important diagnostic considerations. Ideally, she should undergo a cardiac stress test to look for signs of coronary artery disease. In addition, because of her age and weight loss, he recommended endoscopy to rule out cancer of the stomach or esophagus. If these tests were normal, he would simply treat her heartburn with medications and some dietary advice. When she asked about the costs of the tests, he said it would be over $1,000.

Ms. Wade looked worried and stared at her feet. “Doctor, I can't pay that much.” A discussion ensued in which the physician suggested she go to the public hospital. She responded unfavorably, saying that her sister and an aunt had bad experiences trying to obtain services there: “They lose track of you and make you wait all day to be seen; I can't afford to take the time.” The doctor urged her to reconsider, but she remained adamant. He acknowledged that the hospital's staff were overextended, and began to consider other options.

Although he knew the standard approach for managing such a presentation involved ruling out cardiac disease and a gastrointestinal malignancy, he also recognized that the odds were in her favor that she had neither. The history suggested her condition was gastrointestinal and not cardiac, and in a nonsmoker who was not of East Asian background, malignancy would be unlikely. He thought her poor appetite and weight loss might be related to anxiety.

One option would be to treat her empirically for heartburn by starting a proton pump inhibitor. The risks, of course, were that if her condition were cardiac or if she had a malignancy, the consequences of a delay in diagnosis could compromise care. He also thought about ways to reduce the costs, but his hospital had no charity policy, and there was no way he could affect billings in the cardiology or gastroenterology clinics where she would be referred.

As they discussed various options, the clinic visit ran overtime. Other patients were waiting. The physician realized that if he did not take care of her, she was unlikely to go elsewhere. He urged her to undergo the tests at his facility, even if she only paid a portion of the fee. The hospital would write off the losses as bad debt and refer her bill to collection. However, Ms. Wade did not like the idea of being pursued by a collection agency.

Somewhat reluctantly, he resolved to treat her for heartburn with a $117 per month prescription for a proton pump inhibitor. He explained that since they might be missing a serious condition, he would see her again in 2 to 4 weeks. He was especially anxious to see if she continued to lose weight, raising the suspicion of a malignancy.

As she was leaving, his nurse was able to provide Ms. Wade with some samples of a proton pump inhibitor supplied by a pharmaceutical representative. The doctor reduced the fee of her visit by writing off the professional component of the bill. It was not in his power to cancel the clinic portion, but he undercoded the visit as a 15-minute appointment when in fact she had received more than 30 minutes of his time.

This case provides an opportunity to consider the dilemmas that confront a clinician caring for an uninsured patient. If Ms. Wade had been underinsured, i.e., had health insurance that did not cover the needed services, the physician might have been tempted to manipulate reimbursement rules. In a report of a national survey published this year, 39% of physicians acknowledged manipulating reimbursement rules to obtain coverage for services they perceived as necessary for their patients.3 It is useful to review the federal laws that impact on caring for this population.

GOVERNMENT REGULATIONS

As stated, Ms. Wade was uninsured. Physicians are unlikely to encounter legal difficulties providing uncompensated care to completely uninsured patients.* Since the laws intended to reduce fraud and abuse pertain to arrangements involving third-party payers, there is no violation associated with reducing or waiving a fee when the patient is self-pay.

When patients such as Ms. Wade do have health insurance, but are not covered for needed services or cannot afford a deductible or copayment, physicians may attempt to reduce fees through a variety of billing adjustments. These include undercoding, waiving deductibles or fees above insurance, reducing charges below their usual and customary fee, or not billing at all. However unwittingly, such physicians may be committing technical violations or be engaged in abuse or fraud.

The Office of the Inspector General in the Department of Health and Human Services is charged with monitoring federal health care programs for evidence of fraud or abuse. They are particularly concerned when charge-based providers routinely waive coinsurance or copayment amounts mandated under Medicare. Such practices constitute false claims, are violations of the Medicare and Medicaid antikickback statute, and may result in overuse of products and services funded by Medicare. A false claim occurs, for example, when a physician claims that the charge for a service is $100, but routinely waives a $20 copayment. In such an instance, the de facto charge is $80, and Medicare is paying the full sum rather than 80%. A kickback violation occurs when the routine waiver of co-insurance results in an inducement for beneficiaries to favor a particular provider. When fees are consistently waived, there is potential for overutilization or unfair marketing.4

In 1996, Congress enacted a specific prohibition of the Medicare waiver. However, it is permissible to waive copayments on a case-by-case basis for particular patients when financial hardship is documented. The law makes an exception for such cases.5 What is critical is that such waivers not be routine and not be advertised. Furthermore, providers are expected to document why their patient merits a waiver on financial grounds.

Undercoding, such as billing for a minor visit when the patient received an extended visit, is a misrepresentation of services provided and is a violation of the law. In dealing with federal programs such as Medicare, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) advises physicians to bill for the services they provide. Claims are required to be accurate. When coding is inaccurate, secondary uses of the database are compromised, with potentially serious consequences for other patients. For example, future coverage of services by Medicare and Medicaid could be withheld, based on empirical studies of marred databases showing good outcomes for patients receiving low-intensity care.

Laws similar to those governing payments for federal programs have been widely adopted in various forms by the private sector. Thus, physicians are advised to adhere to them consistently, regardless of the payer. One exception is waiving the entire charge for care, for which there is apparently no ban among private insurers. An example would be waiving the charge for follow-up visits for simple conditions such as otitis media in children.6 Of course, waiving all fees becomes a violation if it is part of a fraudulent scheme that profits the provider directly or indirectly.

DISCUSSION

The dilemmas that confront the clinician when a patient cannot afford medical care raise profound issues of social justice. To what extent is the medically indigent patient a victim of unjust social arrangements? Do we view health care as a public good or defer to political processes, allowing the market and elected officials to determine the form our health care system takes? The discourse on health care as a right is ongoing.7,8

Abstract debates on universal access are of little value to the clinician confronted with an indigent patient. The dyad between physician and patient is pragmatic: medical problems need to be addressed then and there. The physician must do what is best for the patient, within existing constraints.

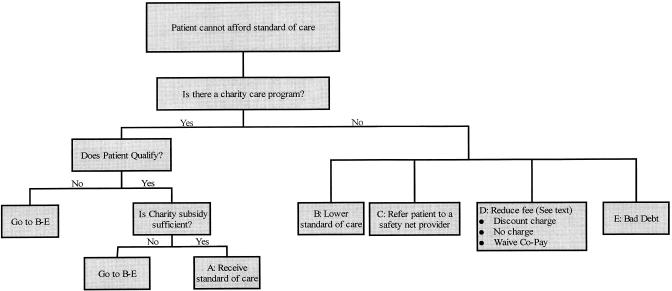

Figure 1 outlines permissible options for a clinician when a patient cannot afford the standard of care. First, the clinician must identify any potential resources for assisting the patient both within and outside of the institution. Oftentimes, social workers can identify appropriate resources. Within the institution, there may be a charity policy. If so, free care or a sliding fee scale is made available to patients who meet the criteria of a means test. Within the community, there may be safety net providers such as federally qualified health centers, board of health clinics, public hospitals, or private physicians who may provide charity services. When less costly care is available elsewhere, physicians confront their first dilemma: Should patients be referred to safety net providers when the cost of care is beyond their means?

FIGURE 1.

Provider options when a patient cannot afford needed care.

What are the ethical implications of terminating the physician-patient relationship because of an inability to pay? Inability is the operative word here, indicating that a patient is medically indigent (as opposed to unwilling to pay). The physician-patient relationship involves mutual responsibilities, and one of those is for the patient to remunerate the physician. But what if the patient is unable to do so? Might it be abandonment to deny further care? Should a long-standing physician-patient relationship be viewed differently than a first visit? What if the patient had simply never been ill before and hence had no prior inclination to see a physician?

What are the quality-of-care implications of terminating the relationship for financial considerations? Will the patient likely receive inferior care if sent elsewhere or, alternatively, better service at a site where costs are less likely to constrain care? Will the resulting delay involved in referral cause harm?

To answer these questions, the physician must consider both the quality of care available at nearby safety net providers, and the likely need for costly tests or interventions. Since public institutions often have more expertise than private practitioners in caring for conditions common among low-income patients and in treating certain subgroups, such as non-English speaking patients and individuals with substance abuse comorbidities, referral may lead to better care. Such forward thinking should begin at the first encounter, so as to avoid embarking on an extensive work-up only to be derailed midstream because of patient concerns about cost. Since patients may not raise concerns about payment until costly tests are required, clinicians should raise the matter with all at-risk patients at the first encounter.

Finally, there is the question of whether a physician is capable of making an unbiased decision about referring a nonpaying patient to another provider. There is a direct conflict of interest when a physician's personal income is at stake. Physicians may be penalized for undue expenses or poor productivity as measured by billing. Safety net providers use the term “dumping” to describe the referral of nonpaying patients to public hospitals when they require expensive care.9

What are the larger consequences of directing indigent patients toward safety net institutions? As both not-for-profit and for-profit providers compete in the marketplace, the nation's most indigent patients are directed to and concentrated at a shrinking number of overburdened safety net institutions.10 The need for free care far exceeds the capacity of public institutions. Is “dumping” unethical because it further weakens our nation's public hospitals and clinics?

If a patient is not referred elsewhere and charity resources are inadequate, the physician must lower the expense and often the standard of care. To do so may be beneficent. If the physician concludes that continuity of care provides a benefit that is greater than referral for services available at lower cost elsewhere, such a decision may be justified. Given his concerns about fragmented care and the quality of services available at the local safety net institution, the physician caring for Ms. Wade might reasonably have reached this conclusion. In retaining responsibility for an indigent patient, then, he faces his second dilemma: Should a physician lower the standard of care for financial reasons when a patient's health may suffer?

What is meant by the concept of a “standard of care?” In legal parlance, the phrase refers to the evidence-based consensus of a panel of experts as to the best approach to a clinical problem.11 For many conditions, there is considerable disagreement about the standard of care. There may be insufficient outcomes data, and no “standard” can take into consideration unique features of individual cases. That is the job of a physician.

The expert consensus in the literature is that weight loss in a patient aged more than 50 years with new symptoms of heartburn is an indication for endoscopy.12 In the literature, however, endoscopy is performed with good follow-up and in a timely fashion. When the standard of care is unavailable to the uninsured or underinsured patient, it may not be realistic for the physician to require such a standard. Problems of social justice cannot be solved in the doctor's office.

Ms. Wade must understand that the decision to decline referral to the county hospital for endoscopy carries risk. Nevertheless, her concerns about delays in care and poor follow-up should be respected. Given the impact of her insurance status, the standard of care as derived in the research setting is not available to Ms. Wade. Finally, there is the patient's concern about her work responsibilities. In the judgment of the physician, following her closely and conservatively may be the best course available.

For patients to share in the decision about the best course of action, they must be fully informed about the potential risks and benefits of their various options. This principal of informed consent, which is commonly applied to clinical care decisions, must encompass dilemmas resulting from financial constraints when they exist.

As shown in Figure 1, the third set of issues physicians must address pertain to the billing procedure. In the case of Ms. Wade, the physician undercoded the office visit and waived the professional fee, without any documentation of her need. Had she been insured by the government or privately, he would have put his institution at legal risk. In striving to aid patients financially, then, the physician faces a third dilemma: Should a physician adjust billing or claims information to reduce costs for an indigent patient?

Although it is not known how frequently physicians who care for indigent patients undercode visits or waive fees, in the report of a national survey cited above, a sizable minority of physicians reported other types of reimbursement manipulations intended to benefit patients, including exaggerating the severity of conditions, altering billing diagnoses, and/or fabricating signs or symptoms to secure coverage.3 The American Medical Association and the American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine along with other professional bodies have declared that manipulating payment claims is unethical as a method of advocating for patients.13,14 The HCFA states that its regulations, which are designed to prevent abuse and fraud, should not prevent the clinician from reducing fees exclusively for an indigent patient's benefit. Problems may be aggravated when clinics have not developed adequate protocols for adjusting fees. If the physician caring for Ms. Wade had been able to refer her for a means test and sliding fee scale, he might have achieved the same reduced fee without miscoding the visit.

LIABILITY

Nearly all physicians think about issues of liability when they think about the standard of care. In civil court hearings for malpractice, disputes of quality of care often revolve around questions of the standard of care, and whether the patient received it.15 Expert testimony is summoned to define the standard.

When a patient does not receive the standard of care, documentation is especially critical. The physician must chart why a particular nonstandard plan of care was selected and that the patient was informed of the risks involved. In the case of Ms. Wade, the physician would need to document, for example, that although he has informed her that endoscopy is indicated, she cannot afford the procedure and declines referral to a public facility. He would then need to explain why following her conservatively (treating her with medicine and watching her clinically) is the best option under the circumstances.

While good documentation is a physician's best asset in court,16 a good physician-patient relationship is the best protection against legal conflict.17 When a physician works as an ally to assist an indigent patient in obtaining medical services, the physician has an opportunity to build an honest, therapeutic relationship. When a patient is turned away, that opportunity is lost. The literature suggests that patients are most likely to be angered if they feel abandoned.18 It appears unlikely, then, that the physician assumes greater liability by working with indigent patients than by turning them away.

SHARED DECISION MAKING

Shared decision making describes a partnership between physician and patient in which each contributes equally to the decision making process.19 For example, how do physicians deal with conflicting responsibilities to individual patients and to the population? Should the physician caring for Ms. Wade weigh the impact of referring an uninsured patient to the county hospital on an already overburdened safety net? Are there ways to help her choose between missing work waiting for medical care at the county hospital and the increased peace of mind that may come from knowing her actual cancer and heart disease risk, and from avoiding the bill collector?

Theories of distributive justice, such as utilitarianism and egalitarianism, have emphasized the importance of applying decision-making principals uniformly and consistently.20,21 By what criteria does one define consistency? Ms. Wade's physician may be consistent in abiding by a framework that adapts to the needs and wishes of each patient. Such an approach emphasizes patient autonomy, and, as one scholar writes, “clinicians should be exempt from normal social ethics so they are free to pursue the objective welfare of patients.”22 While the decision making process should rest on rational principals, the physician's judgment must reach beyond algorithms to consider each case's unique circumstances.

Patients such as Ms. Wade must choose among options for which the outcome is uncertain. Preferences under conditions of uncertainty are called utilities (as opposed to values, which reflect choices among known outcomes). There are a variety of methodologies for measuring preferences including standard gamble,23 time trade-off, and categorical rating techniques which include magnitude estimation, equivalence, willingness-to-pay,24 and, most recently, multiattribute utility theory.25 The guided decision-making process, known as utility analysis, involves describing options, outlining all evidence for possible outcomes, and measuring preferences.26 In essence, it is a weighing of risks. Various patient decision support tools have been studied for predefined “utility sensitive”27 dilemmas such as whether to initiate hormone replacement therapy in perimenopausal women,28 whether to prescribe warfarin for chronic atrial fibrillation,29 and how to select among equivalent therapies for prostate cancer.25 Unfortunately, formal utility analysis is time consuming and has been developed using predefined variables, as in the examples above.

While developments in decision analysis are promising, unanswered questions remain about eliciting preferences and incorporating them in clinical encounters under “crushing time pressures.”30 Until an investigator can demonstrate how formal methods of decision analysis can be applied to a patient's unique circumstances during a routine 20-minute clinical encounter, they will not be applicable to cases such as Ms. Wade's. Nevertheless, familiarity with these methods may facilitate shared decision making as a more informal process.

GUIDELINES

The principal thesis of this article is that when financial considerations intervene in decision making for the individual patient, the clinician is forced off of well-trodden clinical pathways, leaving uncertainty about what is best for the patient. In instances where physicians are forced to compromise the standard of care, there is a potential reduction in quality. Such instances will occur until there is universal access to a basic standard of care. If the art of medicine is applying the science of medicine to the context of the patient, the artful physician will provide the best care possible under the circumstances. The following are proposed as guidelines.

Physicians should explicitly ask about financial concerns rather than ignore the problem or wait for patients to raise the issue first. As with other sensitive questions physicians ask, patients may react with anxiety or discomfort, but the information they provide is important to the care plan. If financial considerations will affect the delivery of medical services, it is better to know sooner rather than later. This will enable the clinician, before embarking on an extensive work-up, to consider the ramifications of transferring a patient with a particular medical need to an indigent care facility versus retaining the individual with a goal of providing care at lower cost.

Physicians need to be knowledgeable about the resources available at their institution and in the community for the medically indigent, so they can maximize services that aid their underinsured patients. They may benefit from ancillary staff, often in social work, who can provide appropriate guidance and referral information. They should be certain that their patients with financial hardship are getting full benefit from the public and private resources that are available, such as public aid and pharmaceutical industry indigent drug programs.

In considering whether to retain a patient or refer to a safety net provider, physicians must take into account the loss of continuity of care and uncertainties about the level of service available at alternative sites. They should also consider that services might be better elsewhere if the referral option is an academic institution or the patient is from an ethnic minority group with which the safety net provider is especially familiar. If a decision is made to refer, the physician should make direct contact with providers at the referral site to identify a contact liaison to optimize the referral process.

If retaining a patient appears to be the preferable or only option, a physician may be forced to provide a nonstandard approach to care in order to best serve that individual. Documentation that a patient has declined a recommended study or therapy, including referral to a safety net provider, if available, and has been informed of the risks involved is critical. In such cases, close observation with frequent visits and basic laboratory studies can be an inexpensive alternative to ordering costly tests (which may have only a marginal benefit over careful observation). The relationship that develops in this setting can be a patient's lifeline when a strong physician advocate who knows the patient well is needed.

Physicians should actively work to lower the cost of their services when they have clear evidence of financial hardship. For underinsured patients, they must do so in a manner that will not be interpreted as financially self-serving or in violation of the law. For uninsured patients, adjustments in fees are allowed. When the demand for free care threatens the financial viability of the provider institution, the physician can promote the adoption of charity policies that help direct subsidies to the most needy patients.

To best serve their patients in the broadest terms, physicians must address issues of social justice outside of the office. Within their institution, they can lobby for a charity care policy, the use of means testing, and the application of sliding fee scales. In their community and through professional societies, they can lobby for support of safety net institutions, such as publicly funded hospitals and clinics. At a state and national level, they can participate in educating the public about the consequences of unaffordable health insurance for tens of millions of Americans. Finally, they can advocate for reforms that will broaden access to medical care and services, including medications and supplies.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Gordon D. Schiff, MD for careful review of the manuscript and helpful suggestions which led to substantive changes.

Footnotes

An exception is when certain state- or county-funded providers forbid the giving away of publically owned goods and services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuttner R. The American health care system. Health insurance coverage. New Engl J Med. 1999;340:163–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann JM, Melnick GA, Bamezai A, Zwanziger J. A profile of uncompensated hospital care, 1983–1995. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997;16:223–32. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wynia MK, Cummins DS, VanGeest JB, Wilson IB. Physician manipulation of reimbursement rules for patients: between a rock and a hard place. JAMA. 2000;283:1858–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Special Fraud Alert, Routine Waiver of Medicare Part B Copayments and Deductibles. 1994. 59 Federal Register 65373.

- 5.Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. 1996. § A(c)(5)

- 6.Rathbun KC, Richards EP. Professional courtesy. Mo Med. 1998;95:18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozar DT. Justice and a universal right to basic health care. Soc Sci Med. 1981;15:135–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wing KR. The right to health care in the United States. Ann Health Law. 1993;2:161–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bindman AB, Grumbach K. America's safety net. The wrong place at the wrong time? JAMA. 1992;268:2426–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.268.17.2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baxter RJ, Mechanic RE. The status of local health care safety nets. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997;16:7–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feasby C. Determining standard of care in alternative contexts. Health Law J. 1997;5:45–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talley NJ, Axon A, Bytzer P, Holtmann G, Lam SK, Van Zanten SV. Management of uninvestigated dyspepsia: a Working Party report for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology 1998. Aliment Pharmacology and Ther. 1999;13:1135–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chicago, Il: American Medical Association; 1997. Health Care Fraud and Abuse: Report of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs and the Council on Medical Service of the American Medical Association. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ann Intern Med. Fourth edition. Vol. 128. American College of Physicians; 1998. Ethics Manual; pp. 576–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King JY. Practice guidelines and medical malpractice litigation. Med Law. 1997;16:29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irving AV. Twenty strategies to reduce the risk of a malpractice claim. J Med Pract Manage. 1998;14:130–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levinson W, Roter D, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capen K. Prevention should be the preferred insurance program for all physicians. CMAJ. 1996;154:138–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards A, Elwyn G. The potential benefits of decision aids in clinical medicine. JAMA. 1999;282:779–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.8.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsen JA. Theories of justice and their implications for priority setting in health care. J Health Econ. 1997;16:625–39. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(97)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKneally MF, Dickens BM, Meslin EM, Singer PA. Bioethics for clinicians: 13. Resource allocation. CMAJ. 1997;157:163–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veatch RM. Allocating health resources ethically: new roles for administrators and clinicians. Front Health Serv Manage. 1991;8:3–29. 43–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llewellyn-Thomas H, Sutherland HJ, Tibshirani R, Ciampi A, Till JE, Boyd NF. The measurement of patient's values in medicine. Med Decis Making. 1982;2:449–62. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8200200407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flowers CR, Garber AM, Bergen MR, Lenert LA. Willingness-to-pay utility assessment: feasibility of use in normative patient decision support system. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:223–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman GB, Elstein AS, Kuzel TM, Nadler RB, Sharafi R, Bennett CL. A multi-attribute model of prostate cancer patients' preferences for health states. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:171–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1008850610569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor TR. Understanding the choices that patients make. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000;13:123–33. doi: 10.3122/15572625-13-2-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kassirer J. Incorporating patients' preferences into medical decisions. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1895–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holmes-Rovner M, Kroll J, Rovner DR, et al. Patient decision support intervention: increased consistency with decision analytic models. Med Care. 1999;37:270–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Protheroe J, Fahey T, Montgomery A, Peters T. The impact of patients' preferences on the treatment of atrial fibrillation: observational study of patient-based decision analysis. Brit Med J. 2000;320:1380–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7246.1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, et al. Users' guides to the medical literature XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the User's Guide to patient care. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:1290–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]