Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To use an electronic medical record to measure rates of compliance with the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) cholesterol guidelines for secondary prevention, to characterize the patterns of noncompliance, and to identify patient and physician-specific correlates of noncompliance.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional descriptive analysis of data extracted from an electronic medical record.

SETTING

Nineteen primary care clinics affiliated with a tertiary academic medical center.

PATIENTS

All patients who visited their primary care physician in the preceding year who met criteria for secondary prevention of hypercholesterolemia.

INTERVENTIONS

None. The main outcome was rate of compliance with NCEP cholesterol guidelines.

MAIN RESULTS

Of 2,019 patients who qualified for secondary prevention, only 31% were in compliance with NCEP recommendations, although 44% were on lipid-lowering therapy. There was no low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) on record within the last three years for 771 (38%), and another 809 (40%) had a recent LDL-C that was above the recommended target of 100 mg/dL. Of the latter group, 374 (46%) were not on a statin, including 188 patients with an LDL-C >130 mg/dL. Compliance among secondary prevention patients with cerebrovascular or peripheral vascular disease, but not coronary disease, was even lower: 19% versus 36%, P < .0001. Most of the additional noncompliant patients never had an LDL-C checked. Patient-specific factors associated with compliance included having seen a cardiologist (45% vs 21%); having had a recent admission for myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or angina (41% vs 26%); being male (37% vs 24%); and being white (34% vs 26%). Patients over 79 and under 50 years old also were less likely to be compliant (22% vs 34% for 50–79 year olds). There were no significant differences in compliance rates based on physician-specific factors, such as level of training, gender, or panel size.

CONCLUSION

We found poor compliance with nationally published and well-accepted guidelines on diagnosing and treating hypercholesterolemia in secondary prevention patients. Compliance was unrelated to physician or physician-specific characteristics, but it was especially low for women, African Americans, patients without a cardiologist, and patients with cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular disease.

Keywords: cholesterol guidelines, NCEP, compliance, electronic medical record, computers, information systems

Early epidemiological work, small clinical trials, meta-analyses, and angiographic studies have suggested that lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels reduces the risk of recurrent cardiac events.1–4 Recently, three large clinical trials (4S,5 CARE,6 and Post-CABG7) have shown that the use of statin drugs to lower LDL-C levels by 20% to 30% can achieve mortality and morbidity benefits of 25% to 40%, similar in magnitude to the benefits accrued from aspirin8,9 and β-blockers.10,11

Despite the wide dissemination of cholesterol management guidelines based on this evidence, significant proportions of targeted populations are not being identified and adequately treated.12–14 Many factors may explain the lack of adherence to practice guideline recommendations among physicians. Among these are imprecise language, lack of incorporation into the clinical workflow, unavailability at the point of care, and physician disagreement with guidelines.15

A variety of strategies can be used to combat these barriers. For example, a computerized decision support system can ensure that guideline information is displayed for any qualifying patient at the most relevant point in the care process. However, this has proven to be difficult, and most computer reminder systems to date have had only marginal impacts.16 Part of the failure is that current patterns of noncompliance, including patient and provider-specific correlates of noncompliance, have not been well studied. This information is needed to overcome the obstacles that impede compliance.

Electronic medical records (EMRs) provide an opportunity within large populations to identify specific areas for improving compliance with practice guidelines. We used such an EMR to evaluate compliance with the secondary prevention portion of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) guidelines.17 Our specific goals were (1) to identify patients qualifying for secondary prevention; (2) to define patterns of noncompliance according to whether there was failure to initiate therapy, failure to optimize therapy, or failure to diagnose or monitor; and (3) to assess patient-level and physician-level correlates of noncompliance.

METHODS

Patient Population

The study was conducted at Brigham and Women's Hospital, a 700-bed urban academic medical center. Included were all patients without contraindication to statin therapy who had visited their primary care physician between October 15, 1997 and October 14, 1998 and who met NCEP criteria for secondary prevention of atherosclerotic disease. These qualifying diagnoses were coronary artery disease (angina, myocardial infarction, or history of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery), cerebrovascular disease (transient ischemic attack, stroke, or history of carotid endarterectomy), or peripheral vascular disease (claudication, or history of peripheral angioplasty or bypass). These diagnoses were captured from the physician-maintained problem lists of the outpatient EMR. This problem list is quite accurate: in a random sample of all ambulatory patients, the positive predictive value of having coronary disease or diabetes mellitus when such a diagnosis is recorded in the EMR was 94% and 96%, respectively; the negative predictive value was 100% (A. Karson, MD, MPH, verbal communication, September 1999).

Baseline patient characteristics were collected from the electronic medical record, including age, gender, race, insurance, qualifying diagnoses, comorbid illnesses (Table 1), cholesterol-lowering medications, and ambulatory visit histories. Physician-specific characteristics were also recorded, including age, gender, specialty, level of training, type and size of practice, volume of visits, and percentage of patient panels with qualifying diagnoses.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| n | % or SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients (N = 2,019) | ||

| Average age, y | 68 | 12.6 |

| Male | 1,033 | 51.2 |

| Race* | ||

| White | 1,201 | 68.2 |

| African American | 397 | 22.6 |

| Hispanic | 123 | 7.0 |

| Other | 39 | 2.2 |

| Insurance* | ||

| Commercial | 137 | 6.9 |

| Capitated/managed care | 466 | 23.5 |

| Medicare | 1,204 | 60.7 |

| Medicaid | 142 | 7.2 |

| Free/self-pay | 33 | 1.7 |

| Secondary prevention diagnosis | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 1,392 | 68.9 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 577 | 28.6 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 391 | 19.4 |

| 2 of above diagnoses | 273 | 13.5 |

| 3 of above diagnoses | 34 | 1.7 |

| Current lipid-lowering treatment | ||

| 0 medications | 1,121 | 55.5 |

| 1 medication | 857 | 42.4 |

| 2 or more medications | 41 | 2.0 |

| Comorbidities† | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 500 | 24.8 |

| Hypertension | 1,095 | 54.2 |

| Nonischemic heart disease | 141 | 7.0 |

| Pulmonary disease | 258 | 12.8 |

| Renal disease | 107 | 5.3 |

| Liver disease | 54 | 2.7 |

| Nonvascular neurologic disease | 107 | 5.3 |

| Malignancy | 235 | 11.6 |

| Major psychiatric disease | 203 | 10.1 |

| Primary care physicians (N = 200) | ||

| Male | 113 | 56.5 |

| Specialty | ||

| Internal medicine | 155 | 77.5 |

| Cardiology | 18 | 9.0 |

| Other | 27 | 13.5 |

| Level of training | ||

| House staff | 82 | 41.0 |

| Junior faculty | 91 | 45.5 |

| Senior faculty | 27 | 13.5 |

| No. of secondary prevention patients seen during the year | ||

| <10 | 147 | 73.5 |

| 10+ | 53 | 26.5 |

| Percent of primary care provider's patient panel qualifying for secondary prevention | ||

| <5 | 112 | 56.0 |

| 5–10 | 56 | 28.0 |

| >10 | 32 | 16.0 |

Race was missing or unreported for 259 patients. Insurance status was missing or unreported for 37 patients.

Nonischemic heart disease was defined as primary or idiopathic cardiomyopathy or valvular heart disease; pulmonary disease as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or bronchiectasis; renal disease as nephrotic syndrome, chronic renal insufficiency, end-stage renal disease, or dialysis; liver disease as chronic hepatitis, hepatitis C infection, or cirrhosis; nonvascular neurologic disease as dementia, Parkinson's disease, seizure disorder, mental retardation, cerebral palsy, or multiple sclerosis; malignancy as any nonskin cancer, plus melanoma; and major psychiatric disease as schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disease.

Primary and Secondary Endpoints

The primary outcome was the rate of compliance with the NCEP cholesterol guidelines. Secondary prevention patients were considered to be compliant if their most recent LDL-C level within the last 3 years was 100 mg/dL (2.59 mmol/L) or 130 mg/dL (3.37 mmol/L) if not on a statin. These criteria are based on the NCEP's recommended target LDL-C, and the threshold LDL-C to start pharmacological therapy immediately, for patients with documented atherosclerotic disease. LDL-C was measured directly using the Sigma antibody and solvent isolation method if specifically requested or if the triglyceride level was >400 mg/dL; otherwise, LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald formula.18

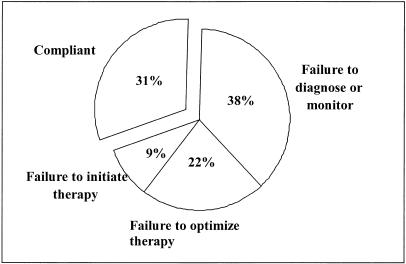

Secondary outcomes were rates of specific noncompliant states: 1) failure to diagnose or monitor hypercholesterolemia (the proportion of secondary prevention patients without an LDL-C in the last three years); 2) failure to optimize therapy (the proportion of patients on a statin whose most recent LDL-C was >100 mg/dL); and 3) failure to initiate therapy (the proportion of patients not on a statin whose most recent LDL-C was >130 mg/dL). All other patients, that is, those with at least one recorded LDL-C in the last 3 years ≤100 mg/dL, or ≤130 mg/dL if not on a statin, were considered to be compliant. Only statins were considered, as opposed to other lipid-lowering medications, because only 3% of patients on any lipid-lowering medication were not on a statin; furthermore, including nonstatins did not significantly change the results.

Analysis

Fisher's exact test or χ2was used for all comparisons of proportions. Given the large number of candidate correlates of compliance which were tested, the threshold for statistical significance was set at P = .005. Multivariable logistic regression was used to adjust for confounding. Because of the high prevalence of the outcome, odds ratios obtained from the logistic regression were converted to risk ratios.19 General estimating equations were used to evaluate correlation or clustering between patients of the same physician. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 6.12 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

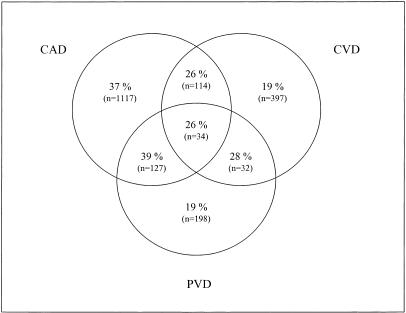

Of 48,811 patients who visited their primary care provider (PCP) within the preceding year, 2,061 (4.2%) qualified for secondary prevention by NCEP cholesterol guidelines criteria. Forty-two patients who had allergies or intolerance to statins were excluded, leaving 2,019 eligible patients. Of these, 1,392 had coronary artery disease (CAD), 577 had cerebrovascular disease (CVD), and 391 had peripheral vascular disease (PVD) documented on their physician-maintained electronic problem lists; 15% had more than one qualifying diagnosis (Table 1). The average age was 68 ± 13 years; 51% were male; and 68% were Caucasian. The average total cholesterol level was 197 ± 43 mg/dL,* LDL-C 119 ± 37 mg/dL,* HDL-C 45 ± 15 mg/dL,* and triglycerides 208 ± 142 mg/dL.† Almost half the patients (42%) had seen a cardiologist at least once in the last year. Regarding pharmacological therapy, 44% were currently receiving one or more medications for hyperlipidemia, which in most cases (89%) was a statin alone. Less than 3% were on a lipid-lowering regimen that did not include a statin; classifying these patients as if they were on a statin did not change the results.

The patients were followed by a total of 200 physicians at 19 different practices. Of the primary care physicians, 22% were subspecialists, including 18 cardiologists and 5 endocrinologists. Forty-one percent of the PCPs were trainees (interns or residents), 45% were junior faculty, and 14% were senior faculty (Table 1).

Among the 2,019 qualifying patients, only 439 (22%) were at or below the 100 mg/dL target recommended by the NCEP guidelines. There was no LDL-C on record for 535 (27%), and 236 (12%) had none in the last 3 years (187 of these were >100 mg/dL at their last measurement). Of the remaining 809 patients, 435 were being treated suboptimally with a statin, and 374 were not on a statin at all, despite 188 with a recent LDL-C >130 mg/dL, the threshold for initiating statin therapy according to the NCEP guidelines. Overall, only 625 (31%) were compliant according to our adapted NCEP guideline criteria (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Overall rate of compliance and noncompliance with National Cholesterol Education Program secondary prevention guidelines.

Compliance among secondary prevention patients with CAD was higher than for patients without CAD (36% vs 19%; P < .00001). Interestingly, the opposite relationship was true for CVD: 21% with CVD versus 35% without (P < .00001). While the diagnosis of PVD was neutral with respect to compliance (27% with PVD versus 32% without, P = .07) in the univariate analysis, compliance appeared to be inversely associated when stratified into the different categories of overlapping secondary prevention qualifying diseases (Figure 2). This was confirmed in the multivariate analysis (see Table 4).

FIGURE 2.

Rate of compliance with National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines among patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease (CVD), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), or any of their combinations.

Table 4.

Adjusted* Risk Ratios†(RR) of compliance with National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines for secondary prevention ( N = 1728)

| 95% CI | RR | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient gender | ||

| Male | 1.00 | |

| Female‡ | 0.71 | 0.59 to 0.85 |

| Patient race | ||

| White | 1.00 | |

| African American§ | 0.70 | 0.54 to 0.89 |

| Hispanic | 1.17 | 0.87 to 1.49 |

| Other | 1.30 | 0.81 to 1.84 |

| Patient age, y | ||

| <50 | 0.67 | 0.46 to 0.94 |

| 50–79 | 1.00 | |

| 80+§ | 0.70 | 0.54 to 0.88 |

| Patient insurance | ||

| Commercial | 1.00 | |

| Capitated/managed care | 1.01 | 0.73 to 1.34 |

| Medicare | 1.03 | 0.76 to 1.34 |

| Medicaid | 0.78 | 0.48 to 1.17 |

| Self/free care | 0.73 | 0.32 to 1.36 |

| Secondary prevention diagnosis∥ | ||

| CAD only | 1.00 | |

| CVD only‡ | 0.64 | 0.49 to 0.81 |

| PVD only§ | 0.62 | 0.44 to 0.85 |

| CAD and CVD | 0.65 | 0.45 to 0.90 |

| CAD and PVD | 1.06 | 0.80 to 1.33 |

| CVD and PVD | 0.83 | 0.42 to 1.40 |

| All three | 1.19 | 0.46 to 2.03 |

| Cardiology visit in the last year | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes‡ | 1.92 | 1.66 to 2.18 |

Adjusted for primary care provider (PCP) gender, specialty, and training; practice location, size, and composition; the number of visits in the last year with the patient's PCP; and patient comorbidities (coded individually, as listed in Table 1). None of these variables was statistically correlated with compliance.

Risk ratios were calculated from the odds ratios.19

P ≤ .001.

P ≤ .005.

CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Other important patient-specific factors that were associated with higher compliance included male gender (37% vs 24%); white race (34% vs 26%); and age 50–79 years (34% vs 22% for patients under 50 or over 79 years old); P < .00001 for all comparisons (Table 2) Neither insurance status nor any comorbid illness (coded as separate independent variables) was a statistically significant correlate of compliance.

Table 2.

Compliance by Subgroups Table 2

| Patients, n | Compliant, % | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient subgroups | |||

| Patient gender | <.00001 | ||

| Male | 1,033 | 37.3 | |

| Female | 986 | 24.3 | |

| Patient race* | <.00001 | ||

| White | 1,201 | 34.3 | |

| African American | 397 | 20.9 | |

| Hispanic | 123 | 36.6 | |

| Other | 39 | 38.5 | |

| Patient age | <.00001 | ||

| <50 | 162 | 21.6 | |

| 50–79 | 1,510 | 33.9 | |

| 80+ | 347 | 22.5 | |

| Insurance* | .30 | ||

| Noncapitated commercial | 137 | 35.0 | |

| Capitated or managed care | 466 | 32.0 | |

| Medicare | 1,204 | 31.2 | |

| Medicaid | 142 | 24.7 | |

| No insurance | 33 | 24.2 | |

| Number of visits to the PCP in the last year | .35† | ||

| 1–2 | 846 | 29.9 | |

| 3–4 | 599 | 31.2 | |

| 5+ | 574 | 32.2 | |

| Number of visits to a cardiologist in the last year | .001† | ||

| 0 | 1,172 | 21.2 | |

| 1–2 | 498 | 40.4 | |

| 3–4 | 227 | 48.5 | |

| 5+ | 122 | 54.1 | |

| Primary care physician Subgroups | |||

| Specialty | .28 | ||

| Internal medicine | 1,716 | 30.3 | |

| Cardiology | 68 | 39.7 | |

| Endocrinology | 64 | 29.7 | |

| Other | 171 | 34.5 | |

| Level of training | .70 | ||

| Trainee | 332 | 31.3 | |

| Junior faculty | 1,329 | 30.4 | |

| Senior faculty | 358 | 32.7 | |

| Volume of secondary prevention patients | .87 | ||

| High (≥10 patients/year) | 1,530 | 30.9 | |

| Low (<10 patients/year) | 489 | 31.3 | |

| Percent of patient panel made up by secondary prevention patients | 0.55 | ||

| <5 | 1,088 | 30.8 | |

| 5–10 | 794 | 30.5 | |

| >10 | 137 | 35.0 | |

| Primary care provider gender | 0.59 | ||

| Male | 1,254 | 31.4 | |

| Female | 765 | 30.2 | |

| Practice location | 0.69 | ||

| On site | 1,293 | 30.6 | |

| Off site | 726 | 31.5 |

Race was missing or unreported for 259 patients. Insurance status was missing or unreported for 37 patients.

Mantel-Haenszel test for trend.

Compliance was higher among patients who had visited a cardiologist (45% vs 21%; P < .00001), with increasing compliance noted as the number of visits with a cardiologist increased ( P = .001 for trend). Conversely, there was no significant difference in compliance based on frequency of visits with the primary care physician, nor with physician-specific factors, such as specialty, level of training, gender, panel size, volume of secondary prevention patients, percentage of secondary prevention patients, or location of practice (Table 2).

Among the subgroups, the reasons for noncompliance were fairly uniform. On average, 40% to 60% was failure to diagnose or monitor, 25% to 45% was failure to optimize therapy, and 5% to 15% was failure to initiate therapy (Table 3)

Table 3.

Distribution of Noncompliance, n (%)

| No recent LDL-C* | 771 (38%) | |

| No LDL-C ever | 535 (27) | Failure to diagnose |

| No LDL-C in last 3 y | 236 (12) | Failure to diagnose |

| Recent LDL-C 101–130 | 430 (21) | |

| On statin | 244 (12) | Failure to optimize |

| Not on statin | 186 (9) | (Compliant) |

| Recent LDL-C > 130 | 379 (19) | |

| On statin | 191 (9) | Failure to optimize |

| Not on statin | 188 (9) | Failure to treat |

| Overall noncompliance | 1,394 (69) |

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level.

When adjusted for other variables, including patient gender, race and age, qualifying secondary prevention diagnosis, and involvement with a cardiologist remained significant correlates of compliance. In particular, females, African Americans, patients younger than 50 or older than 79 years, patients without CAD, and those without a cardiologist had about 30% lower likelihood of being in compliance with NCEP guidelines (Table 4). In the multivariable model, compliance was not significantly correlated with patient insurance status, any of the comorbidities (including the total number of comorbidities for each patient), nor any physician-specific variables, including gender, specialty, level of training, or patient panel characteristics. Furthermore, using generalized estimating equations to control for clustering effect by physician did not change the results by more than 5%, so only the logistic regression is presented.

The results also were not significantly different when the compliance definition was liberalized by (a) crediting any lipid-lowering medication instead of just statins and (b) loosening the LDL-C targets to 110 mg/dL on therapy and 140 mg/dL off therapy. Overall compliance in this case was still less than 39%.

DISCUSSION

These results document suboptimal management of hypercholesterolemia among patients with coronary, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular disease. In this population of patients with high risk for recurrent atherosclerotic events, the prevalence rate of having a recent LDL-C <100 mg/dL on statin therapy, or <130 mg/dL off such therapy, was only 31%. We used a rather conservative definition of compliance, because the NCEP guidelines recommend that secondary prevention patients have annual LDL-C measurements, and that the target LDL-C for such patients be <100 mg/dL. The rates of adherence to NCEP guidelines achieved at our institution were similar to those reported at other institutions, 30% to 50%,12–14 but would have been lower had the NCEP definition of compliance been strictly applied.

Adherence was associated with patient-specific factors, including gender, race, and age. Female, African American, poor or uninsured, and elderly patients have been shown to have poorer access, inferior quality of care, and worse outcomes in studies of cardiac procedures20–24; but this has not been previously reported with respect to cholesterol management. In the case of the gender and age discrepancies, the explanation partly may be secondary to poor dissemination or acceptance of data which show that women with vascular disease have just as much to gain, and the elderly perhaps even more to gain, from aggressive lipid management. The decreased adherence for African-American patients is more difficult to rationalize. The lack of association with insurance status may be a power issue, as the number of uninsured patients in our study was low.

In comparison, adherence rates appeared to be independent of physician-specific factors, including correlation among patients with the same physician. Though the participation of a cardiologist was strongly associated with adherence, the patients of primary care physicians trained as cardiologists were not more compliant than the patients of general internists. Male physicians were as likely as females, senior physicians as likely as junior physicians and trainees, and “experienced” physicians as likely as “less experienced” ones (as measured by volume and percentage of secondary prevention patients seen) to diagnose and treat hypercholesterolemia (Table 2). This suggests that significant knowledge deficits among physicians is not the cause of low guideline compliance, except perhaps the importance of managing cholesterol in patients with cerebrovascular or peripheral vascular disease but not coronary artery disease.

Instead, other factors may represent confounders, including some of the characteristics of the visit itself. For instance, screening and treatment of hypercholesterolemia are more likely to occur during visits whose scope is limited to health maintenance or to cardiovascular disease. Moreover, the health maintenance visit may be a marker for younger and healthier patients motivated to participate in secondary prevention; and the cardiovascular visit a marker for patients with more severe coronary artery disease or fewer multiple other medical problems. This suggests that interventions that are directed at the visit itself, as opposed to the physician, may be more successful at improving compliance.

Our results extend the work of previous studies by excluding patients with documented allergies or intolerance to statins, including patients with noncardiovascular atherosclerotic disease, and correcting for physician-specific as well as patient-specific characteristics, including comorbid illnesses. Furthermore, our study classified noncompliance into different types of failures, revealing that the most common shortcoming in lipid management is poor screening and monitoring, followed closely by poor dose adjustment for those patients already being treated for elevated cholesterol. Only 10% of the noncompliance was from failure to initiate therapy after obtaining an LDL-C result >130 mg/dL.

These data suggest that reminders to check lipid levels regularly will have relatively little impact on overall adherence, and may explain why some reminder systems to date have been only marginally effective.16 This is because reminders to optimize therapy already prescribed are traditionally lacking, as are reminders that hypercholesterolemia in patients with noncardiovascular atherosclerotic disease must also be aggressively treated. Reminders may also have to be tailored to the age, gender, and race of the patient in order to overcome disparities based on these qualities. Finally, interventions directed at the visit itself (health maintenance or problem focused) may be more successful, or at least complementary, to reminders sent to primary care physicians.

Our study demonstrates how electronic medical records with coded problem and medication lists can be used to collect and analyze information regarding physician practice behavior. This method can be modified for use in longitudinal monitoring. We plan to use this information to develop a sophisticated reminder system to help address the deficiencies discussed above.

There are a number of possible shortcomings of our study method. The most important is the accuracy of the record, which at our institution is maintained by physicians. If physicians fail to update their patients' records regularly, measurement bias will occur. As noted in the methods, the overall accuracy of the electronic record was high, but variation among physicians in the completeness of their patients' problem lists was not evaluated. However, this would not bias the results unless there is low correlation between the accuracy of the problem lists and the accuracy of the medication lists, which is unlikely because both are maintained by the same physician. Measurement bias could occur if some physicians rely extensively on off-site laboratories for lipid level measurements, but this occurs rarely in the setting in which this study was undertaken.

Another limitation of this study is that the outcome was compliance in the prescribing practices of physicians, not in the behavior of patients. For instance, if the patient simply declined the recommendation of the physician, failed to fill the prescription, or did not take the doses, these patients would more likely be noncompliant due to failure to start or to optimize therapy. Notably, we did not find a significant relationship between compliance and patient insurance status, but this was a crude marker of socioeconomic status, which along with other factors, may affect patient behavior and compliance. These are important to elucidate, because interventions to improve physicians' prescribing habits may not be effective for this subset of patients, who may require complementary interventions targeted directly to them.

We also could not control for potentially confounding visit-related factors, such as the “reason” for a patient's appointment. As discussed above, this may partially explain the dramatic positive influence that cardiology visits had on compliance, but the lack of effect that primary care physician visits had. Elucidating these visit-specific factors may also be important for improving compliance, but they were not readily available even in our comprehensive electronic medical record.

Finally, our study was conducted in an academic, tertiary care setting. The results may not be generalizable to private or community practices, where the make-up of physicians, patients, and payors, as well as the electronic medical record and health care delivery system, may vary substantially. Even though this study controlled for a robust set of possible confounders, it is possible that there may be regional or other differences in performance with NCEP guidelines.

We conclude that compliance with nationally published and relatively well-accepted guidelines on management of hypercholesterolemia in secondary prevention patients was poor, and it was even lower when such patients did not have documented coronary disease or were not followed by a cardiologist. Compliance was associated with patient characteristics, including gender, race, and age; but was independent of physician demographic factors. Further, failure to titrate lipid-lowering therapy was a common cause of nonadherence which may be amenable to reminders distinct from those which promote general screening and monitoring of lipid levels.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by RO1 HS07107 from the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Rockville, Md.

Footnotes

Multiply mg/dL by 0.0259 to convert to mmol/L.

Multiply mg/dL by 0.0113 to convert to mmol/L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gordon T, Kannel WB, Castelli WP, Dawber TR. Lipoproteins, cardiovascular disease, and death: the Framingham study. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:1128–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipid Research Clinics Program. The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial results. II. The relationship of reduction in incidence of coronary heart disease to cholesterol lowering. JAMA. 1984;251:365–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holme I. An analysis of randomized trials evaluating the effect of cholesterol reduction on total mortality and coronary heart disease incidence. Circulation. 1990;82:1916–24. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.6.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown G, Albers JJ, Fisher LD, et al. Regression of coronary artery disease as a result of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in men with high levels of apolipoprotein B. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1289–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011083231901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet. 1994;344:1383–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Post Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Trial Investigators. The effect of aggressive lowering of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and low-dose anticoagulation on obstructive changes in saphenous-vein coronary-artery bypass grafts. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:153–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701163360301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. ISIS-2: 10 year survival among patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction in randomised comparison of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither. BMJ. 1998;316:1337–43. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antiplatelet Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy—I: Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ. 1994;308:81–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turi ZG, Braunwald E. The use of beta-blockers after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1983;249:2512–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freemantle N, Cleland J, Young P, Mason J, Harrison J. Blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis. BMJ. 1999;18:1730–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7200.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schectman JM, Elinsky EG, Bartman BA. Primary care clinician compliance with cholesterol treatment guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:121–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02598306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troein M, Gardell B, Selander S, Rastam L. Guidelines and reported practice for the treatment of hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. J Intern Med. 1997;242:173–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcelino JJ, Feingold KR. Inadequate treatment with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors by health care providers. Am J Med. 1996;100:605–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317–22. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92244-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adult Treatment Panel II. Summary of the second report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. JAMA. 1993;269:3015–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bairaktari E, Hatzidimou K, Tzallas C, et al. Estimation of LDL cholesterol based on the Friedewald formula and on apo B levels. Clin Biochem. 2000;33:549–55. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(00)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:221–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107253250401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayanian JZ, Udvarhelyi IS, Gatsonis CA, Pashos CL, Epstein AM. Racial differences in the use of revascularization procedures after coronary angiography. JAMA. 1993;269:2642–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson ED, Shaw LK, DeLong ER, Pryor DB, Califf RM, Mark DB. Racial variation in the use of coronary-revascularization procedures. Are the differences real? Do they matter? N Engl J Med. 1997;336:480–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702133360706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenneker MB, Weissman JS, Epstein AM. The association of payer with utilization of cardiac procedures in Massachusetts. JAMA. 1990;264:1255–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone PH, Thompson B, Anderson HV, et al. Influence of race, sex, and age on management of unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: the TIMI III registry. JAMA. 1996;275:1104–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]