Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The One-Minute Preceptor (OMP) model of faculty development is used widely to improve teaching, but its effect on teaching behavior has not been assessed. We aim to evaluate the effect of this intervention on residents' teaching skills.

DESIGN

Randomized controlled trial.

SETTING

Inpatient teaching services at both a tertiary care hospital and a Veterans Administration Medical Center affiliated with a University Medical Center.

PARTICIPANTS

Participants included 57 second- and third-year internal medicine residents that were randomized to the intervention group (n = 28) or to the control group (n = 29).

INTERVENTION

The intervention was a 1-hour session incorporating lecture, group discussion, and role-play.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Primary outcome measures were resident self-report and learner ratings of resident performance of the OMP teaching behaviors. Residents assigned to the intervention group reported statistically significant changes in all behaviors (P < .05). Eighty-seven percent of residents rated the intervention as “useful or very useful” on a 1–5 point scale with a mean of 4.28. Student ratings of teacher performance showed improvements in all skills except “Teaching General Rules.” Learners of the residents in the intervention group reported increased motivation to do outside reading when compared to learners of the control residents. Ratings of overall teaching effectiveness were not significantly different between the 2 groups.

CONCLUSIONS

The OMP model is a brief and easy-to-administer intervention that provides modest improvements in residents' teaching skills.

Keywords: medical education, internship and residency, educational models, feedback

Residents play a critical role in the education of medical students and interns,1 and report spending significant amounts of time teaching medical students and colleagues.2 Without specific training in educational methods, residents may be less efficient and less effective in their teaching. Many programs to improve resident teaching have been developed, but training sessions have been time-intensive for both the resident participants and the faculty teaching the courses.3,4 Sessions lasting multiple half-days may be optimal, but are logistically difficult to arrange. A recent controlled trial found a 3-hour teaching improvement course to be effective, but that study was not randomized.5 Short teaching improvement courses may be more feasible and respectful of resident's limited time, but require rigorous evaluation to ensure they are effective. As such, we designed a randomized, controlled trial of a brief intervention in order to prove both the feasibility and efficacy of the course.

The One-Minute Preceptor (OMP) model of faculty development6 is a popular and widely used method for improving teaching skills. Originally designed for use by faculty in busy ambulatory practices, it facilitates efficient clinical teaching with the use of 5 “microskills” to help the mentor guide the teaching interaction. The 5 microskills are:

Get a commitment—i.e., ask the learner to articulate his/her own diagnosis or plan;

Probe for supporting evidence—evaluate the learner's knowledge or reasoning;

Teach general rules—teach the learner common “take-home points” that can be used in future cases, aimed preferably at an area of weakness for the learner;

Reinforce what was done well—provide positive feedback; and

Correct errors—provide constructive feedback with recommendations for improvement.

Strengths of this model are that it can be taught in a single 1- to 2-hour seminar and that it focuses on a few teaching behaviors that are easily performed. This model appears optimal for resident teaching during call nights or work rounds as they face similar time pressures as ambulatory preceptors. They also do the majority of teaching in case-based format rather than lecture, which makes this model an ideal choice to adapt for their use.

In the original description of the model,6 the authors reported on a follow-up survey of 36 faculty members 4 years after participating in the seminar. Of 29 respondents, 90% reported using material from the workshop in greater than 90% of teaching encounters. All respondents believed the model was at least “somewhat helpful,” while 58% thought it was “extremely helpful” to them as clinical teachers. The authors did not directly measure the use of the microskills in faculty teaching and it is not known if increasing the use of those microskills improves students' perception of their mentors' overall teaching skills.

The primary purpose of our study was to determine if residents who were trained in the model were rated more highly as clinical teachers than those who did not receive this training. We also wondered if this model was useful to the intervention group and if their self-reported use of the microskills changed from pre- to post-intervention.

METHODS

Participants in the study were internal medicine residents assigned to inpatient medical services at the University of Michigan and the Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Medical Center between March and May, 1999. Residents were excluded if they did not have teaching responsibilities (e.g., no medical students or interns were assigned to their service). Subjects were randomized to the intervention or control group by a random number generator. The intervention occurred mid-month, with outcome assessment occurring pre- and postintervention. Informed consent was obtained along with institutional review board approval.

The intervention occurred in the middle of the ward month, with the intervention group meeting for a 1-hour session over lunch. An average of 9 residents was present at each of these monthly sessions. The OMP model was taught in a 15-minute lecture, followed by 20 minutes of role-play and debriefing, in which a resident practiced the model with a colleague playing the role of the student. The facilitator then led a 15-minute discussion of the use of the OMP model in the residents' teaching setting. Pocket reminder cards were then given to residents, and each resident was asked to state his/her goals for teaching using the model.

Our primary outcome measure was change in student ratings of resident use of these teaching skills at the end of the rotation (post-intervention). Secondary outcome measures included resident self-report of pre- and post-intervention use of the teaching skills, as well as resident self-report of the usefulness of the OMP model at the end of the rotation.

To test these outcomes, we developed a 14-item questionnaire to assess the 5 microskill domains in the OMP model. Residents and students were asked to rate resident behavior using a standard 5-point rating scale (1 = “strongly disagree” and 5 = “strongly agree” for use of behavior, and 1 = “very poor” and 5 = “excellent” for measures of overall effectiveness). Six of the 14 items were derived from a previously validated instrument.7 See Table 1 for a list of the questions. Questionnaires were pretested for clarity with both students and interns.

Table 1.

Survey Items from the Student Evaluations of Resident Teaching

| Domain | Item |

|---|---|

| Commit | 1. Asked for my diagnosis, work-up, or therapeutic plan before their input. |

| Commit | 2. Involved me in the decision-making process. |

| Probe | 3. Asked me for the reasoning behind my decisions. |

| Probe* | 4. Evaluated my knowledge of medical facts and my analytic skills. |

| General Rules | 5. Taught general rules or “pearls” that I can use in future patient care. |

| Feedback | 6. Gave me positive feedback on things I did correctly. |

| Feedback* | 7. Explained why I was correct or incorrect. |

| Feedback* | 8. Offered suggestions for improvement. |

| Feedback* | 9. Gave feedback frequently. |

| Overall | 10. Ability to improve my physical exam skills. |

| Overall | 11. Organization of work rounds. |

| Overall | 12. Efficiency of work rounds. |

| Overall* | 13. Ability to motivate you to do outside reading. |

| Overall* | 14. Overall teaching effectiveness |

Items derived from a previously validated instrument.

For the primary outcome measure of student evaluation of resident teaching skills, we used a paired t test to compare the magnitude of change in teaching ratings between the intervention and control groups for each item. As the unit of analysis was the resident-learner dyad and each resident had multiple raters, we performed an analysis for clustering and found no significant differences when examining the effect of an individual resident.8 This enabled us to pool the student ratings within the intervention and control groups rather than perform a hierarchical analysis of students within resident within intervention group. For resident self-report of their use of the teaching behaviors, we used paired t tests to compare pre- and post-intervention ratings. Significance level was set at P = .05. All data was analyzed using STATA statistical software (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex).

RESULTS

Fifty-seven residents agreed to participate and were randomized, 28 to the intervention group and 29 to the control group. Survey response rates were 90% for study residents and 80% for interns and students.

There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics of the intervention and control groups regarding age, gender, level of training, and previous exposure to teaching improvement programs. As shown in Table 2, baseline teaching ratings were also similar, with only 1 survey item demonstrating significant differences in pre-intervention ratings. The intervention group had lower baseline scores on 1 item in the domain of “feedback.”

Table 2.

Ratings of 57 Residents by 120 Interns and Medical Students at the University of Michigan Comparing Pre- and Postintervention Ratings in Intervention and Control Groups

| Control group | Intervention group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Item | Pre | Post | Change | Pre | Post | Change | Mean Difference in Change Between Groups |

| Commit | Ask for diagnosis. | 3.94 | 3.83 | −0.11 | 3.98 | 4.09 | 0.11 | 0.22 |

| Commit | Involve in decision making. | 4.18 | 4.01 | −0.17 | 4.03 | 4.23 | 0.20 | 0.37* |

| Probe | Asked for my reasoning. | 4.18 | 4.01 | −0.17 | 4.07 | 4.18 | 0.11 | 0.28 |

| Probe | Evaluated my knowledge. | 3.89 | 3.70 | −0.19 | 3.83 | 3.97 | 0.14 | 0.33* |

| Rules | Taught general rules or pearls. | 4.14 | 4.00 | −0.14 | 4.00 | 4.08 | 0.08 | 0.22 |

| Feedback | Gave positive feedback. | 4.12 | 4.14 | 0.02 | 4.03 | 4.27 | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| Feedback | Explained why I was correct/incorrect. | 4.18 | 4.03 | −0.15 | 4.07 | 4.19 | 0.12 | 0.27 |

| Feedback | Offered suggestions for improvement. | 3.77 | 3.64 | −0.13 | 3.42 | 3.95 | 0.53 | 0.66* |

| Feedback | Gave feedback frequently. | 3.64 | 3.44 | −0.20 | 3.33 | 3.93 | 0.60 | 0.80* |

| Overall | Physical exam skills. | 3.51 | 3.38 | −0.13 | 3.59 | 3.67 | 0.08 | 0.21 |

| Overall | Work rounds organization. | 3.96 | 3.94 | −0.02 | 3.96 | 3.90 | −0.06 | −0.04 |

| Overall | Work rounds efficiency. | 4.12 | 4.22 | 0.10 | 4.00 | 4.12 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

| Overall | Motivate you to do reading. | 3.86 | 3.66 | −0.20 | 3.78 | 3.93 | 0.15 | 0.35* |

| Overall | Overall teaching effectiveness. | 4.13 | 4.00 | −0.13 | 4.07 | 4.07 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

Significant at P < 0.05 using t tests for mean change in teaching ratings.

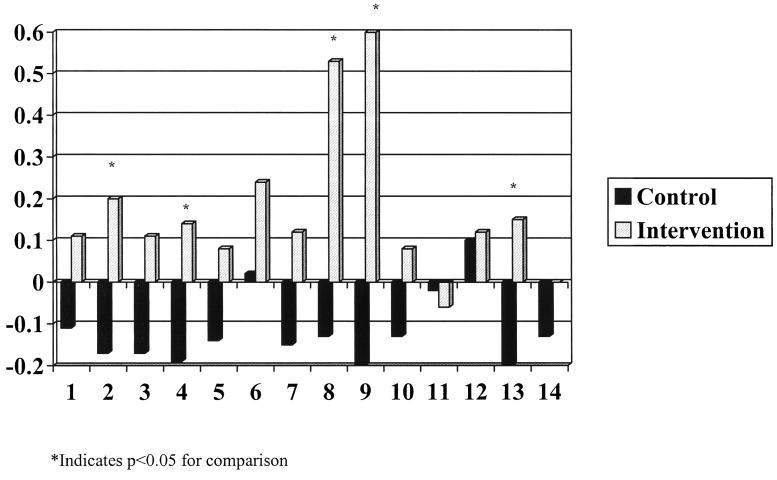

For the primary outcome of student rating of residents' teaching skills, we found that residents assigned to the intervention group showed statistically significant improvements in at least one item in all domains except “teaching general rules.” The greatest impact on teaching scores was seen in the items that address “asking for a commitment,”“providing feedback,” and “motivating me to do outside reading.” No difference was seen in measures of overall teaching effectiveness, except for the question addressing whether students were “motivated to do outside reading. ”Table 2 shows the magnitude of change in teaching scores pre- and post-intervention, with graphical representation of these changes shown in Figure 1. The intervention group showed improvement in nearly all survey items compared to controls, reaching statistical significance as noted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Mean change in teaching ratings of 57 residents by 120 interns and medical students, by survey question.

The secondary outcomes included resident self-report of the use of these teaching skills and resident satisfaction with the model. Residents reported statistically significant improvement in all tested items except “teaching general rules” (Table 3)

Table 3.

Changes in 28 Intervention Residents' Self-reported Use of Teaching Skills using a Scale of 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree

| Domain | Item | Pre | Post | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commit | Ask for diagnosis. | 3.73 | 4.26 | <.01 |

| Commit | Involve in decision making. | 3.71 | 4.34 | <.01 |

| Probe | Asked for my reasoning. | 3.41 | 4.17 | <.01 |

| Probe | Evaluated my knowledge. | 3.30 | 4.08 | <.01 |

| “Pearls” | Taught general rules or pearls. | 3.73 | 4.02 | .10 |

| Feedback | Gave positive feedback. | 3.80 | 4.26 | .03 |

| Feedback | Explained why I was correct/incorrect. | 3.60 | 4.13 | <.01 |

| Feedback | Offered suggestions for improvement. | 3.23 | 4.00 | <.01 |

| Feedback | Gave feedback frequently. | 3.15 | 3.89 | <.01 |

| Overall | Work rounds organization. | 3.21 | 3.97 | <.01 |

| Overall | Work rounds efficiency. | 3.45 | 4.00 | <.01 |

| Overall | Overall teaching effectiveness. | 3.36 | 4.08 | <.01 |

Significance determined by t tests for mean with P = .05.

On the measure of resident satisfaction with the OMP model, 87% of the intervention group rated the model as “useful or very useful,” a mean rating of 4.28 on the 1 to 5 scale (standard deviation, 0.65).

DISCUSSION

A 1-hour intervention improved the teaching skills of residents. The greatest effects were “getting a commitment,”“feedback,” and “motivated me to do outside reading.” Residents were able to alter their responses to students' presentations by restraining their desire to elicit from the student more data about the patient and instead, solicit the thinking of the student. Perhaps this ease of adoption is possible because residents' teaching habits are not as highly ingrained as in faculty members and therefore are more amenable to change.

The One-Minute Preceptor model helped to overcome one of the most pervasive and difficult problems in clinical education—the lack of feedback. At baseline, provision of feedback was the lowest rated item by students for the intervention group and the next to lowest for the control group. Residents in the intervention group reported significant improvements in giving feedback and student ratings confirmed this improvement. The present intervention is one of the few that have demonstrated improved outcomes in this area. Perhaps the reason for this is that feedback is not stored as generalizations to be shared at the end of the month evaluation, but rather, as specific responses to immediate actions on the part of the student.

The item “motivated me to do outside reading” showed significant improvement in the intervention group. The OMP model specifically instructs the teacher to “get a commitment” from the learner prior to giving his/her own opinion. This process may increase motivation for reading by students, as they are expected to generate their own complete plan and know that they will be critiqued based on that plan. This model, therefore, may be useful in promoting self-directed learning, which is a critical tool in the development of future physicians.

Student ratings of teacher performance showed improvements in all domains except “Teaching General Rules.” This microskill may also be the most difficult for residents to develop. In earlier research, Irby described the development of teaching scripts in experienced teachers.9,10 These scripts allow teachers to present pearls or teaching points effortlessly because they are well developed in memory. Residents as novice teachers may not have as well developed teaching scripts. Thus, a short teacher-training event would most likely have little immediate impact on this skill because teaching scripts are acquired over longer periods of time. In the intervention, the “Teaching General Rules” microskill was described as coming up with a common “pearl” or “rule of thumb” that they have found helpful with patient care. As General Rules are not always apparent in that brief moment, “teach what students need to know” was offered as an alternative for residents. Initially, the control group had slightly higher ratings on this item. The intervention group improved slightly on this item, but that improvement did not reach statistical significance. Surprisingly, ratings of this item were generally high compared with other items, suggesting either a ceiling effect, or that the provision of content was perceived to be an important part of their teaching task and one that they did relatively well. These two factors may have limited our ability to detect significant changes in resident behavior.

These positive results did not result in differentiating the intervention and control groups on student ratings of the overall teaching effectiveness. While there are many possible reasons for this, the most likely may be that the subset of teaching skills that we measured may not be the most highly correlated with measures of overall teaching effectiveness.4 In other studies of clinical teaching effectiveness, the primary correlate of overall teaching effectiveness is enthusiasm and stimulation of interest. Because this was neither taught in the model nor rated by our instrument, there is no way to know if the intervention influenced this aspect of teaching.11 A previous study by Spickard et al.5 taught techniques to improve both feedback and learning climate in a 3-hour intervention. This intervention demonstrated improvement in both learning climate and feedback skills and a trend toward improvement in overall teaching ratings. We believe this supports the hypothesis that overall teaching is correlated more with enthusiasm than with other factors. Together, these studies demonstrate that improving overall teaching ratings is more complex than providing one or two skills for teachers to work on. One other possible reason for our findings is that although the residents were trained to provide evaluation and feedback, the training was incomplete, so that evaluation was incomplete or the feedback was delivered without regard to proper technique.12,13 Further attention to technique may improve the overall rating of resident teaching if the feedback is seen as constructive and supportive.

While the intervention group ratings by students improved, the control group ratings declined. This has been previously described by Skeff,14 and may reflect teacher fatigue that occurs late in the month. This mid-month intervention may also serve to remind residents of the importance of ongoing feedback and evaluation when they might have otherwise foregone these actions.

Because this study was performed at a single institution, this may limit generalizability. The duration of the intervention and follow-up were brief. This brief study duration was helpful in that it occurred in “real-time” and allowed evaluation of paired surveys from resident-student interactions pre- and post-intervention. It is also a limitation, though, in that we were unable to examine the durability of the intervention's effect over multiple months. Further studies will need to address the longevity of this effect. We were unable to blind residents or students to group assignments. Theoretically, this could lead to a halo effect, where students might rate residents generally higher when they knew they had received such training. However, this does not appear to be a factor given the non-significant changes in ratings of “overall teaching effectiveness.” We also did not provide the control group with a sham intervention, such as a reminder that teaching is an important part of their job. This alone might result in teaching improvement by combating teacher fatigue. The nature of our results, though, with improvement in evaluation and feedback, but not in overall teaching effectiveness, indicates a more focal effect of the intervention. Because of limitations in sample size, this study was powered to a 70% chance to detect an effect size of 0.5 units on the 5-point scale. Last, the high baseline ratings in all categories indicate a possible ceiling effect that limits our ability to detect differences in the two groups.

In conclusion, the One-Minute Preceptor model of faculty development is a brief, easy-to-administer intervention that provides improvements in resident teaching skills. Further study is needed to determine the durability of the results, as well as to validate its usefulness at other institutions. Future studies should examine the effect of a series of brief interventions to see if they are effective at improving overall teaching ratings.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilkerson L, Lesky L, Medio F. The resident as teacher during work rounds. J Med Educ. 1986;61:823–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonesk X. The house officer as a teacher: what schools expect and measure. J Med Educ. 1979;54:613–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jewett LS, Greenberg LW, Goldberg RM. Teaching residents how to teach: a one-year study. J Med Educ. 1982;57:361–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkerson L, Irby DM. Strategies for improving teaching practices: a comprehensive approach to faculty development. Acad Med. 1998;73:387–96. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spickard A, Corbett EC, Schorling JB. Improving residents' teaching skills and attitudes toward teaching. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:475–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02599042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neher JO, Gordon KC, Meyer B, Stevens N. A five-step “microskills” model of clinical teaching. Clin Teach. 1992;5:419–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litzelman D, Stratos G, Marriot D, Skeff K. Factorial validation of a widely disseminated educational framework for evaluating clinical teachers. Acad Med. 1998;73:688–95. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199806000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huber PJ. Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. Vol. 1. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1967. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditions. pp. 221–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irby D. How attending physicians make instructional decisions when conducting teaching rounds. Acad Med. 1992;67:630–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irby D. What clinical teachers in medicine need to know. Acad Med. 1994;69:333–42. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irby D, Rakestraw P. Evaluating clinical teaching in medicine. J Med Educ. 1981;56:181–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250:777–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewson M, Little M. Giving feedback in medical education: verification of recommended techniques. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:111–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skeff K. Evaluation of a method for improving the teaching performance of attending physicians. Am J Med. 1983;75:465–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90351-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]