Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the frequency and determinants of provider nonrecognition of patients' desires for specialist referral.

DESIGN

Prospective study.

SETTING

Internal medicine clinic in an academic medical center providing primary care to patients enrolled in a managed care plan.

PARTICIPANTS

Twelve faculty internists serving as primary care providers (PCPs) for 856 patient visits.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

Patients were given previsit and postvisit questionnaires asking about referral desire and visit satisfaction. Providers, blinded to patients' referral desire, were asked after the visit whether a referral was discussed, who initiated the referral discussion, and whether the referral was indicated. Providers failed to discuss referral with 27% of patients who indicated a definite desire for referral and with 56% of patients, who indicated a possible desire for referral. There was significant variability in provider recognition of patient referral desire. Recognition is defined as the provider indicating that a referral was discussed when the patient marked a definite or possible desire for referral. Provider recognition improved significantly (P < .05), when the patient had more than one referral desire, if the patient or a family member was a health care worker and when the patient noted a definite desire versus a possible desire for referral. Patients were more likely (P < .05) to initiate a referral discussion when they had seen the PCP previously and had more than one referral desire. Of patient-initiated referral requests, 14% were considered “not indicated” by PCPs. Satisfaction with care did not differ in patients with a referral desire that were referred and those that were nor referred.

CONCLUSIONS

These PCPs frequently failed to explicitly recognize patients' referral desires. Patients were more likely to initiate discussions of a referral desire when they saw their usual PCP and had more than a single referral desire.

Keywords: managed care, patient satisfaction, referral desire

The role of many primary care physicians (PCPs) has altered in recent years in concert with market-driven changes in health care. For example, in many managed care systems, PCPs act as gatekeepers responsible for authorizing access to specialty, emergency, and hospital care.1 Authorization of access to specialty care has important implications for health care utilization, expenditures, and PCP function. On one hand, specialty referrals are often associated with significant economic implications and do not always improve outcome.1–6 On the other hand, patients have a relatively high degree of desire for specialist referral,7–12 and PCP failure to recognize these desires have been associated with lack of clinical improvement and dissatisfaction with care.11,13–16

Despite the obvious importance of the managed care referral process, there is remarkably little information on patient–PCP interaction in this process.13,14,17,18 One survey revealed that many PCPs feel patients view managed care PCPs as adversaries (66%), that managed care regulation of specialist referrals negatively impacts patient care (57%), and that managed care impairs physician–patient communication (37%).18 The present study was therefore undertaken with several goals in mind. We primarily wanted to determine the frequency with which PCPs recognize patient referral desires and to see if we could identify factors associated with increased PCP recognition of these desires in an academic managed care setting. We also wanted to delineate circumstances in which patients are more likely to initiate a referral discussion with their PCP. Finally, we wanted to assess current patient attitudes toward the referral process and the influence of the referral process on overall satisfaction with care in the studied plan.

METHODS

Patients, Providers, and Setting

The study population consisted of 856 consecutive patients seen at the University Medical Group Practice from September 1997 through December 1997. All patients were enrolled in a University of Colorado managed care program (CU Gold), which utilizes PCPs as gatekeepers for specialty access. Patients in this plan who visit the study site include approximately 3,000 state employees, health care workers, physicians, nurses, university-based employees, and their family members. The University of Colorado managed care plan, implemented in January 1996, represented a change from an open-access health care system. Patients enrolled in the study were presenting to the clinic for a new-patient, a return-patient, or an episodic visit. Patients seeking referral for emergent or urgent care, pregnancy, cancer, mental health, AIDS, annual eye examination, or continuing therapy for any previous referral issued in the past 6 months were excluded. The PCPs in this study consisted of 12 board-certified general internists. Providers were aware of the research study but were unaware of its objectives. All patients were seen by a faculty physician without involvement of medical students or housestaff. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Patient Questionnaire

Demographic data were obtained from the computerized scheduling system used in the clinic. Patients completed a 1-page, self-administered previsit questionnaire and were told their responses would be confidential and not be made known to their physician. All patients were asked to rate their overall health (poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent). Patients were also asked to provide a yes or no response to three questions: “Have you seen a regular care provider at this office before?”“Is this appointment with your PCP?”“Are you or a family member a health care worker?” In addition, patients were asked to indicate the length of the relationship with their PCP (never met, 1 visit, less than 1 year, or more than 1 year). Patients were asked whether they needed a referral to a specialist that same day (yes, possibly, or no). Patients indicating either a definite or possible need for referral were asked to provide a yes or no answer to whether they had more than one referral desire. Patients indicating definite or possible desire for specialist referral were also asked to respond to two other statements regarding their referral desire (“I am worried about this health concern” and “Because of this health concern, I am unable to function normally”) by indicating they strongly disagree, disagree, not sure, agree, or strongly agree with the statements. A randomly selected subset of patients who indicated either yes or possible desire for specialist referral were contacted by telephone 3 to 14 days after the visit. These patients were asked to respond to three statements (“I am satisfied with my medical care for my referral concern.”“I am satisfied with the referral process for my referral desire.”“I think it is a good idea to see my PCP before being referred to a specialist”) on a strongly disagree, disagree, not sure, agree and strongly agree scale.

Provider Questionnaire

The PCPs were asked to conduct patient visits during the study period in their usual fashion. Providers were asked to complete a brief, self-administered questionnaire immediately after each patient visit. Providers were asked to provide a yes or no answer to the question, “Did you discuss a referral today?” If a referral was discussed during the encounter, providers were asked to indicate (yes or no) if a referral was made. When a referral was discussed, providers were asked to identify the main referral concern and whether there was more than one concern. Providers were also asked to indicate if any referral discussion was initiated by the patient or the provider. Providers were asked to provide a yes or no answer to the question, “Was the referral indicated?” For referrals felt to be not indicated, PCPs were asked to indicate why they felt the referral was not indicated from a menu of possibilities (PCP comfortable treating this condition; patient seeks additional reassurance that is not indicated; requested test or treatment not indicated; patient desires to use all benefits of the plan; other). This menu of possibilities was derived after discussion with several experienced PCPs. Both patient and provider questionnaires were reviewed with a professional survey consultant and extensively pretested before implementation.

Statistical Analysis and Definitions

For questions related to overall health, a numerical score was obtained by assigning a score of 1 for poor; 2, fair; 3, good; 4, very good; or 5, excellent. For statements regarding worry, ability to function normally regarding the referral desire, and opinion regarding satisfaction with care, a score was assigned of 1 for strongly disagree; 2, disagree; 3, not sure; 4, agree; or 5, strongly agree. For this study, we defined that physician recognition of a patient referral desire occurred when the physician noted that a referral was discussed when patients indicated a desire (yes or possible) for a referral. Analyses were performed on SPSS-PC version 4.2 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill). Initially, continuous variables were tested using t tests and analysis of variance where appropriate, and categorical variables were compared using χ2tests. Because a relatively small number (n = 12) of physicians were involved in this study, we did further analyses. In order to account for possible clustering by physician, a mixed effects linear model was used. These analyses were conducted using the Proc Mixed procedure in the SAS (version 6.12) statistical package. The P values for the variables in Tables 1–3 are expressed in terms of this mixed linear model. A P value < .05 is considered significant.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with a Referral Desire with Whom Primary Care Providers (PCPs) Did and Did Not Discuss the Referral Concern

| Patient Referral Desire | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Not Discussed by PCP (n = 179) | Discussed by PCP (n = 171) | P Value* |

| Appointment with usual PCP, % | 67.2 | 68.7 | .64 |

| Known PCP >1 y, % | 50.3 | 49.4 | .99 |

| Health care worker or family member, % | 47.5 | 58.8 | .025 |

| More than one referral concern, % | 20.5 | 33.5 | .004 |

| Patient noted “possible” referral need, % | 56 | 44 | NS |

| Patient noted “definite” referral need, % | 27 | 73 | .0001 |

| Patient self-rating of overall health, mean ± SEM | 3.6 ± 0.07 | 3.7 ± 0.07 | .72 |

| Patient self-rating of worry regarding referral concern, mean ± SEM | 3.5 ± 0.07 | 3.6 ± 0.08 | .86 |

| Patient self-rating of functional status related to referral concern, mean ± SEM | 2.8 ± 0.10 | 2.5 ± 0.11 | .45 |

NS indicates not significant.

Table 3.

Patients with a Referral Concern: Perceptions and Attitudes Toward Overall Care and the Referral Process

| Variable | Not Referred | Referred | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient rating of overall satisfaction with care, mean ± SEM | 4.2 ± 0.08 | 4.1 ± 0.09 | .36 |

| Patient rating of satisfaction with the referral process, mean ± SEM | 3.7 ± 0.09 | 3.9 ± 0.08 | .18 |

| Patient response to the statement, “It is a good idea to see my primary care provider before specialist referral,” mean ± SEM | 3.5†± 0.06 | 3.2†± 0.05 | .51 |

| Patient rating of strongly agree or agree with referral process, % | 54.8 | 74.7 | NS |

NS indicates not significant.

P < .05 versus patient rating of overall satisfaction with care.

RESULTS

Frequency of Patient Referral Desire and Provider Nondiscussion

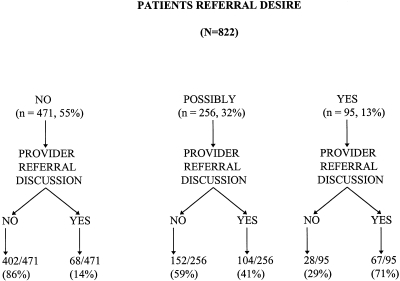

Complete data on 822 of 856 patients were available on patient referral desire and physicians noting whether a referral was discussed. The frequency of patient referral desire and of PCP explicit referral discussion in these 822 visits is shown in Figure 1. The PCPs did not explicitly discuss referral with 59% of patients indicating a possible referral desire or with 29% of those indicating a definite referral desire.

Figure 1.

Patient referral desire and physician provider recognition of these referral desires.

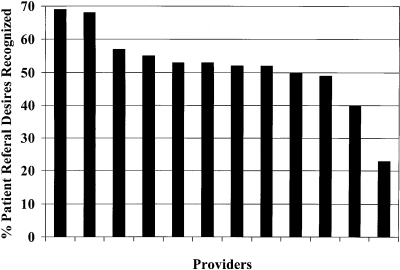

PCP Recognition of Patient Referral Desire

Individual provider recognition of a patient referral desire (patients answering yes or possibly) varied significantly (P < .02) within this group practice and is depicted in Figure 2. We were unable to find a significant relation between PCP age, gender, years in practice, clinic workload, and PCP recognition of patient referral concern (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Individual physician provider recognition of patient referral desire. The percentage of patients with a referral desire that was recognized by individual physicians is on the vertical axis. The solid bars represent individual providers. There was significant interindividual physician variability in recognition of patient referral desire.

Table 1 compares selected visit and patient characteristics for patients with a referral desire in whom PCPs did and did not explicitly recognize this desire. Providers were significantly more likely to recognize a referral desire in patients who were health care workers or family members, in patients who had more than one referral desire, and in patients who had indicated a definite desire versus a possible desire for referral. No differences in patient self-rating of overall health, worry regarding the referral desire, or self-reported lower functional status related to their referral concern were present when the PCP did recognize and did not recognize a referral desire. Duration of patient-provider relationship and seeing the PCP for the referral concern did not improve provider recognition of a referral desire.

Comparison of Patient-Initiated and PCP-Initiated Referral Discussions

Table 2 compares several variables when either the patient or the PCP initiated a referral discussion. This set of data refers to the 239 patients with whom a referral discussion was held. Of these 239 patients, complete data were available on 224. Patients were significantly more likely to have initiated the referral discussion when they had seen the PCP previously and had more than one referral desire. There was a trend for patient initiation of the referral discussion when the patient had known the PCP for more than a year (P = .08 by bivariate analysis, P = .113 by cluster analysis). Patient self-rating of overall health and degree of worry regarding the referral desire did not differ significantly when patient and PCP initiation of a referral discussion were compared. The frequency with which a referral was made was comparable with patient-initiated and PCP-initiated referral discussions.

Table 2.

Comparison of Patient Initiated and Primary Care Provider (PCP)–Initiated Referral Discussions

| Referral Discussion Initiated by | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Patient (n = 115) | PCP (n = 99) | P Value |

| Seen PCP at this office previously, % | 71.6 | 53.5 | .05 |

| Known PCP >1 y, % | 58.1 | 42.3 | .11 |

| More than one referral concern, % | 44.2 | 19.7 | .003 |

| Referral made, % | 53.3 | 46.7 | .58 |

| Self-rating of health, mean ± SEM | 3.7 ± 0.08 | 3.7 ± 0.09 | .88 |

| Self-rating of worry regarding referral concern, mean ± SEM | 3.6 ± 0.11 | 3.6 ± 0.11 | .26 |

| Self-rating of functional status related to referral concern, mean ± SEM | 2.4 ± 0.12 | 2.7 ± 0.14 | .56 |

PCP-Judged Nonindicated Referrals

Overall, 17.4% of referrals that were made were judged by the involved PCPs to be “not indicated.” The involved PCP felt that 13.4% of referrals that were made for patient-initiated referrals were not indicated, while 4.0% of PCP-initiated referrals were not indicated (P < .001). The main reason PCPs felt that referrals were not indicated was that they felt comfortable treating the condition (68.2%). Less often cited reasons included patient sought additional reassurance that was not felt by the PCP to be necessary (13.6%), miscellaneous (13.6%), and patient desired a test or procedure not felt by the PCP to be indicated (4.6%). There were no significant differences in patient self-rating of overall health, concern regarding the referral issue, or functional status relative to the referral issue when referrals judged to be indicated and nonindicated by the PCP were compared (data not shown).

Patient Satisfaction with the Referral Process

Of the 351 patients indicating a referral desire (yes or possibly), 150 were randomly selected for a follow-up telephone survey. Of these 150 patients, 111 could be contacted. Of these 111 patients, 80 were referred and 31 were not. Overall satisfaction with care and the referral process for these patients with a referral desire that were referred and that were not referred are compared in Table 3. Patients who were not referred showed no significant differences in their overall satisfaction with care or satisfaction with the referral process. No significant difference between referred and not-referred patients was found to the statement, “I think it is a good idea to see my PCP before being referred to a specialist.” The mean scores for both referred and nonreferred patients were, however, significantly lower (P < .025) when the responses as to whether it is a good idea to see a PCP before specialist referral were compared with the rating of overall satisfaction with care.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that general internist PCPs did not explicitly discuss a specialist referral in 29% to 59% of patients that answered either “yes” or “possibly” to the query, “Do you need a referral to a specialist today?” Although these results may seem surprising, recent studies by Kravitz et al. indicate a very high overall frequency of unmet patient desires for ambulatory care visits.8,15 Also, analyses of data from two studies, not designed specifically to examine the referral process, reveal a frequency of unmet patient desires for specialist referral of 24% and 58%, respectively.8,11 Together, the present and previous studies indicate significant patient desires for referral to a specialist that may not be directly addressed in general medical ambulatory settings. Moreover, the study of Marple et al. found that a residual desire for subspecialty referral was a powerful, independent correlate of lack of patient satisfaction 2 weeks following the ambulatory encounter (odds ratio, 2.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.5 to 5.4, P = .001).11

Previous studies have emphasized high variability in provider practice patterns including specialist referral rates.17,19–21 Given this variability, it is perhaps not surprising that we found significant PCP variability with regard to explicit recognition of patient referral desires. This variability ranged from an average recognition of 68% to 24% of patient referral desires for individual PCPs. We could not account for this variability by PCP age, gender, years in practice or clinic workload. Three patient factors, being a health care worker, having a definite referral desire versus a possible referral desire, and having more than a single referral desire, were the only factors that we could ascertain to be associated with increased PCP recognition of patients' referral desire. Given data on the frequency with which patients desire specialist referral and the implication of not addressing such desires,8,11 greater PCP awareness and further studies to directly address how to improve PCP recognition of patients' referral desires are warranted.

Inasmuch as PCPs frequently fail to recognize patients' referral desires, we examined patient-initiated referral discussions. Our results indicate that continuity of care and familiarity with their PCP is a significant correlate of patient initiation of a referral discussion (Table 2). Interestingly, these variables are not associated with enhanced PCP recognition of a patient's referral desire (Table 1).

Our results are of interest with regard to another aspect of the referral desires. We found that the PCPs studied felt that a modest proportion (14%) of patient-initiated referral desires were not indicated. Another study has indicated moderate variability in provider responses to patient requests for costly, unindicated services.17 Our recent studies have found that patient need for reassurance, having previously seen a specialist for the same or a similar problem, and the belief that the PCP did not have the requisite expertise to handle the issue are the main factors underlying most patient-initiated referral requests.22 An understanding of factors that motivate patients to request referrals may serve to develop better strategies to handle patient requests felt to be not indicated. However, handling such situations in a cost-effective manner while maintaining patient satisfaction is an area in need of further study.

Another result of note is our finding of slightly positive feelings in our population about the gatekeeper model. This result contrasts somewhat with results reported in 1998 from Israel.12 Our results are based on a relatively small number of patients, and further studies are needed to better address this issue.

Some potential limitations of our study merit consideration. It is possible that in some visits PCPs discussed issues regarding the patient's referral desire without explicitly discussing the need or lack thereof for referral. Such a discussion would have been classified as PCP “nonrecognition” of a patient referral desire in our study. Thus, it is possible that our results overestimate PCP nonrecognition of patient referral desires. Our data on health care workers must be interpreted with caution because our definition may have resulted in a health care worker population consisting of patients who have only workplace contacts with health professionals or the health care field. The expectations of the health care workers, as a group, might become less distinguishable from those of the other subjects if a more rigid definition were applied. Our study did not explicitly differentiate patient desire from expectation in that we asked about “need” for a referral. “Desire” refers to what patients want before their PCP visit, and “expectation” refers to what patients feel they are likely to receive from their PCP. Expectation rather than desire has been shown to impact patient satisfaction.8 Our study was undertaken in a highly selected setting. Thus, our results may not be generalizable. Moreover, physicians, while not knowledgeable about the specific objectives of our study, could surmise that it dealt with patient referral issues, and this knowledge could have influenced our results. Our study included a relatively modest number of PCPs. However, we utilized a mixed effects linear model to account for any effects of cluster randomization due to the modest number of physicians included in our study. We did not study telephone referral requests, which in some systems are an important avenue for specialist access. Our study also did not evaluate the concordance of referral concerns between patients and providers when providers recognized patient referral concerns. Discordance between the patient agenda and physician agenda is well recognized and has prompted study of agenda-setting clinical tools.

In summary, our results demonstrate that these PCPs frequently failed to explicitly discuss patients' specialty referral desires. The PCPs were more likely to recognize a referral desire when the patient was a health care worker, expressed a definite need versus a possible need for referral, and the patient had more than one referral desire. Patients were more likely to initiate a referral discussion in a continuity of care setting in which they were familiar with the PCP. Understanding factors that influence a patient's request for referral and provider recognition of a referral desire may influence patient satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by University Hospital Board of Directors, Denver, Colo.

REFERENCES

- 1.Franks P, Clancy CM, Nutting PA. Gatekeeping revisited–protecting patients from overtreatment. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:424–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208063270613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrest CB, Starfield B. The effect of first-contact with primary care clinicians on ambulatory health expenditures. J Fam Pract. 1996;43:40–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin DP, Diehr P, Price KF, Richardson WC. Effect of a gatekeeper plan on health services use and charges: a randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1628–32. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.12.1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glenn JK, Lawler FK, Hoerl MS. Physician referrals in a competitive environment: an estimate of the economic impact of a referral. JAMA. 1987;258:1920–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenfield S, Nelson E, Zubkoff M. Variations in resource utilization among medical specialties and systems of care: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1992;267:1624–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donohoe MT. Comparing generalist and specialty care: discrepancies, deficiencies and excesses. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1596–608. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webb S, Lloyd M. Prescribing and referral in general practice: a study of patients' expectations and doctors' actions. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:165–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kravitz RL, Cope DW, Bhrany V, Leake B. Internal medicine patients' expectations for care during office visits. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:75–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hornberger J, Thom D, MaCurdy T. Effects of a self-administered pre-visit questionnaire to enhance awareness of patients' concerns in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:597–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kravitz RL, Callahan EJ, Azari R, Antonius D, Lewis CE. Assessing patients' expectations in ambulatory medical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:67–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.12106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marple RL, Kroenke K, Lucey CR, Wilder J, Lucas CA. Concerns and expectations in patients presenting with physical complaints. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1482–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabenkin H, Revital G, Brammli S, Shvartzman P. Views of direct access to specialists. JAMA. 1998;279:1943–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.24.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal TC, Riemenschneider TA, Feather J. Preserving the patient referral process in the managed care environment. Am J Med. 1996;100:338–43. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borowsky SJ. What do we really need to know about consultation and referral? J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:497–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kravitz RL, Callahan EJ, Paternitic D, Antonius D, Dunham M, Lewis CE. Prevalence and sources of patients' unmet expectations for care. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:730–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-9-199611010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerr EA, Hays RD, Lee ML, Siu AL. Does dissatisfaction with access to specialists affect the desire to leave a health plan? J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:77. doi: 10.1177/107755879805500104. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher TH, Lo B, Chesney M, Christensen K. How do physicians respond to patients' requests for costly, unindicated services? J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:663–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman DS, Novack DH, Gracely E. Effects of managed care on physician-patient relationships, quality of care and the ethical practice of medicine. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1626–32. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLeod P, Tamblyn R, Gayton D, et al. Use of standardized patients to assess between physician variation in resource utilization. JAMA. 1997;278:1164–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calman NS, Hyman RB, Hecht W. Variability in consultation rates and practitioner level of diagnostic certainty. J Fam Pract. 1992;35:31–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franks P, Clancy CM. Referrals of adult patients from primary care: demographic disparities and their relationship to HMO insurance. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albertson G, Lin CT, Swaney R, Anderson S, Anderson RJ. Patient-provider interactions in the subspecialty referral process in a gatekeeper model academic managed care plan. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(suppl):103. Abstract. [Google Scholar]